TREASON

Washington DC and

Charleston, South Carolina.

The Civil War started a few hours before dawn this morning. After decades of posturing and skirmishing by politicians, citizens, and bands of thugs, two armies have actually fired upon each other. In the four-month gap between Lincoln’s election in November 1860, and his inauguration in March 1861, seven states have left the union. Instead of merely facing a local rebellion, the U.S. has been attacked by what some people claim to be a new nation, the Confederate States of America, which has been created to protect slave owners.

PALMETTO BUGS

The crisis began in October 1860, a full month before election day, when it was clear that Lincoln had a good chance of winning. The governor of South Carolina secretly invited the governors of other slave states to join in leaving—or “seceding from”—the Union. Most agreed to at least consider it. A few were enthusiastic. The governor of Florida replied that he was “proud to say that Florida will wheel into line with the gallant Palmetto State [South Carolina’s nickname] or any other Cotton State or States…. If there is sufficient manliness at the South to strike for our rights, honor, and safety, in God’s name let it be done before the inauguration of Lincoln.”

THE GAP BETWEEN A PRESIDENT’S ELECTION AND INAUGURATION IS NOW JUST OVER TWO MONTHS.

For thirty years South Carolina had flirted seriously with secession, only to take a step back each time, largely because it might have found itself on its own. The anger reached full boil during the 1860 presidential election campaign. Politicians eager for the South to secede told voters Lincoln and his Republican Party were an immediate threat to the entire South. A lot of people were fooled. Many southerners believed Lincoln was determined to end slavery in the existing slave states. They believed he would give the full rights of citizenship to African Americans. They also believed he wanted to use force to impose his will on them. None of that was true. Although he hated slavery, Lincoln wasn’t planning on giving African Americans the full rights of citizenship, such as the right to vote. (Nor was he planning to give those rights to women, who wouldn’t gain them for another sixty years.) Had the slave states accepted his one unwavering position, that slavery could not be extended into the western states, it’s very possible that Lincoln would have defended the South against demands for the complete abolition of slavery.

Lincoln with his youngest son, Thomas, known to everyone as Tad. This photo was taken on February 1865, when Tad was not quite twelve years old. He and his older brother, Willie (opposite), were rarely disciplined by their parents, and they treated the White House as their own playground. When an invasion of Washington seemed likely at the beginning of the war, Tad and Willie built a play “fort” on the roof to defend the building. They had tutors instead of attending school, and Tad’s education suffered as a result. It’s possible his parents were indulgent because he had many health problems. He passed away just six years after his father’s assassination, at age 18.

Willie Lincoln (above), was Tad’s older brother by a bit more than three years. Although he was the older child in the White House, he was third of four Lincoln boys. The first, Edward, had passed away shortly before turning four. The second, Robert, was a student at Harvard University for most of his father’s presidency.

Willie was more disciplined and thoughtful than Tad, but still able to get into trouble. Unfortunately, in February 1862, a little after this picture was taken, Willie died of what was probably typhoid fever. He was just over eleven years old. Both his parents were inconsolable. Some observers, including the president, believed Mrs. Lincoln’s mental decline after Willie’s death had signs of insanity.

Lincoln was frustrated that proslavery politicians were misrepresenting his positions. After his election, a pro-Union politician in the slave state of North Carolina asked him to make a public statement to calm the people of the South. Lincoln’s reply was snippy, which was unusual. “May I be pardoned,” he wrote, “if I ask whether even you have ever attempted to procure the reading of the Republican platform, or my speeches, by the Southern people? If not, what reason have I to expect that any additional production of mine would meet a better fate?”

The departing president, James Buchanan, made the crisis worse. At the beginning of December 1860, a month after Lincoln’s election but before Buchanan left office, Buchanan attacked “the long continued and intemperate interference…” of the antislavery forces of the North, blaming them entirely for the conflict in his annual message to Congress. He did almost nothing to stop the southern states from seceding, and several members of his cabinet, sympathetic to the slave states, worked secretly to prevent the federal government from taking action.

Buchanan’s defense of the South as it was preparing for secession and war has led many historians to rank him as the worst or among the worst American presidents. However, he did understand southern sentiment. He told Congress that the greatest motivation of the South was that the North’s agitation had inspired the slaves “with vague notions of freedom. Hence a sense of security no longer exists around the family altar. This feeling of peace at home has given place to apprehensions of servile [slave] insurrections. Many a matron throughout the South retires at night in dread of what may befall herself and her children before the morning.”

That fear was probably greatest of all in South Carolina, where slaves outnumbered free whites. Slaves were more than 57 percent of the state’s population on the day the state seceded, December 20, 1860. (Adding the small number of free blacks, the total proportion of African Americans was nearly 59 percent.) Past attempts at uprisings had led South Carolina to enact laws preventing anyone from teaching a slave to read and write. Slaves weren’t allowed to assemble in large numbers.

It’s worth noting that the order in which the other states seceded is almost a perfect match for the relative sizes of their slave populations and white citizens. Mississippi, the state with the second-highest proportion of slaves to free white citizens (55 percent slaves), was the second state to leave the Union. The next four states to leave, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana, all had populations of about 45 percent slaves. Then came five states where slaves were between about 25 and 33 percent of the population.

DATES OF SECESSION AND SLAVE POPULATION

Source: U.S. Census Office, Eighth Census [1860], Population, Washington DC, 1864; and John C. Willis.

It’s possible to look at these statistics and conclude that secession was about money. Slaves equalled property, and each slave had a dollar value. The states whose economies were most dependent on slaves were the first to leave the Union. But that’s only part of the story. The fear of slave uprisings that President Buchanan mentioned also explains the order in which the southern states left. To a great extent, secession was the emotional reaction of a small ruling class who believed—possibly with very good reason—that they would soon lose power and be subject to the rule of people they had treated violently.

“HORNET’S NEST”

As the desire for war grew into a popular mania, Fort Sumter, sitting on an island in Charleston Harbor, became the focus of the warmongers’ attention. Suddenly it became an insult to southerners for a United States fort to sit at the entrance of this important southern port. The federal commander was determined to defend it. While President Buchanan was still in office, the governor of South Carolina ordered a naval blockade to put the fort under siege. Buchanan tried to send relief, but the blockade turned away the federal ships.

When Lincoln took office at the beginning of March, 1861, he inherited this standoff. He recognized it as a test of his will. Although supplies were running low at the fort, the commander refused demands for surrender. To abandon the fort would be to signal his willingness to lose the South forever.

After about a month in office, Lincoln decided to try again to resupply the fort. He sent the governor of South Carolina a letter in advance, promising he was sending only basic supplies the men needed. He would not send ships or troops to break the blockade or attack the South Carolina forces.

The Confederate cabinet met to discuss Lincoln’s message. Instead of responding peacefully, they decided this was the moment to force the question of war. They would demand surrender of the fort, and if their demand was not met they would attack the fort and take it by force.

Some in the Confederate government knew this was a mistake. The Confederate secretary of state, Robert Toombs, who had been one of the most vocal supporters of secession, said the plan to take Sumter “is suicide, murder, and will lose us every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornet’s nest which extends from mountain to ocean, and legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death…. It is unnecessary; it puts us in the wrong; it is fatal.”

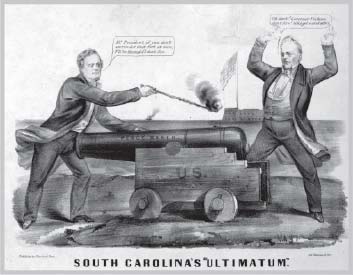

A cartoon from early 1861, soon after the Fort Sumter crisis began. South Carolina governor Francis Pickens (left) is threatening President James Buchanan. He says, “Mr. President, if you don’t surrender that fort at once, I’ll be ‘blowed’ if I don’t fire.” Buchanan answers, “Oh don’t! Governor Pickens, don’t fire! till I get out of office.” The cartoonist thinks the southern threat will backfire.

ROBERT TOOMBS AND SOME OTHER SOUTHERN POLITICIANS WHO’D BEEN FIGHTING FOR YEARS TO SECEDE WERE CALLED THE “FIRE-EATERS” IN THE NORTHERN PRESS.

He understood that the South would be at a great disadvantage in any war. It had half the population of the North—nine million to the North’s twenty-two million. Factories capable of producing military equipment were mostly in the North. The business of the South was still very much to produce raw cotton that was then shipped to factories in the North or in the United Kingdom.

Some southern politicians believed that if war began, a few important European countries, like the United Kingdom, would recognize the Confederacy and give it official status as a country. In return those countries would get valuable trading rights. But others in the South believed that the governments of Europe would be cautious. To recognize the Confederacy might lead to war with the Union. William T. Sherman, who would later become one of the most effective Union generals of the war, said to a southern friend:

You people speak so lightly of war; you don’t know what you’re talking about. War is a terrible thing!…You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people…. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it. The Northern people not only greatly outnumber the whites of the South, but…they can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make…. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with…

If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.

In the end, however, the South was willing to fight a suicidal war to avoid living on equal terms with its slaves. Shortly after Alexander Stephens was sworn in as vice president of the Confederate States of America, he left no doubt about this essential difference in philosophy between the Confederacy and the U.S.:

The prevailing ideas entertained by [Thomas Jefferson] and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically…. Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

So now, on this day, not two months after taking office, Lincoln sees a telegram from the commander of the Union troops at Fort Sumter:

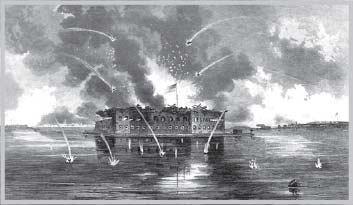

HAVING DEFENDED FORT SUMTER FOR THIRTY FOUR HOURS UNTIL THE QUARTERS WERE ENTIRELY BURNED THE MAIN GATES DESTROYED BY FIRE, THE GORGE WALLS SERIOUSLY INJURED, THE MAGAZINE SURROUNDED BY FLAMES AND ITS DOOR CLOSED FROM THE EFFECTS OF HEAT, FOUR BARRELS AND THREE CARTRIDGES OF POWDER ONLY BEING AVAILABLE AND NO PROVISIONS REMAINING BUT PORK, I ACCEPTED TERMS OF EVACUATION…ROBERT ANDERSON. MAJOR FIRST ARTILLERY. COMMANDING.

This is the event that will shock the North, rally the South, and begin a conflict that will settle the slavery question.

The rebel bombardment of Fort Sumter