PART I: THE EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE FRAMEWORK

The emotional intelligence framework outlined in this part of the book is intended for busy people who want to develop EI but may not have the opportunity to trawl through heaps of heavyweight literature.

The framework describes the four interrelated elements central to an emotionally intelligent approach. These determine how effectively you can understand and interact with other people. Each of these elements involves a wide range of ideas and skills. As well as enhancing your performance, understanding and putting them into practice will have an effect on the mood and sense of comfort you have when dealing with people. Stated simply, the key components are:

- Self-knowledge

- Managing your emotions

- Understanding others’ behaviours and feelings

- Managing your relationships (using effective social skills).

Let’s now look at each of these in more detail.

1. Self-knowledge

Understanding yourself is probably the starting point for emotional intelligence; it provides a foundation for managing yourself, spotting emotions in others and managing the relationships in that situation. When someone mentions self-awareness, the first thing you might think about is how your behaviour affects other people and what they think of you. ‘Seeing ourselves as others see us’ is a mantra heard again and again in relation to communication skills, negotiating, staff management, politics and the media for many years. But what does it mean?

- Think of a person you know and the situations in which you meet them. What are they like? Write a short description.

- Look at the description you have written. How many different factors have you written about? What are the key perspectives that help you to form your opinion about them?

Self-awareness is about understanding ourselves and knowing what pushes our buttons and why.

Our past and our self-image play a large part in how we choose to interpret other people’s behaviour. More importantly they also determine the way we act and the effect we have on others.

When we look at other people, we observe many aspects which shape our perceptions of them. First impressions are important because they influence the way we interpret others’ initial behaviour. These might be based on the manner of the initial contact, their physical appearance, dress, friendliness, manners, accent and many other characteristics.

We all have our own individual behaviours, which shape the judgements people make about us. Such behaviours often stem from our backgrounds or demonstrate what we value. Some of these behaviour-forming factors are:

- The lessons we learned, both as children and later in life, about what is acceptable

- Our needs for affection, warmth or closeness (or coolness, distance and formality)

- The beliefs and principles we hold about ourselves, the way life is, and about other people

- The type of instincts or ‘inner voice’ that gives us insights or tells us what is important

- Our ‘cognitive strategies’ – ways of thinking which determine comfort or discomfort with people and things

- The lifestyle we seek

- The way we want to be seen by others

- The goals we have and our sense of purpose

- The things we dismiss, reject or find difficult to deal with.

It would be great to think of ourselves or others as free agents determining who we are and what we do. Emotional intelligence can help with that. But most of our inner drive, and certainly the way we react to others, comes from our own past experiences. The authority figures we have encountered, our parents or grandparents, the role models we have created and the managers we have worked for – they have all played a role in moulding and conditioning who we are and the effect we create on others. So too does the way we react to the emotions we experience.

Self-awareness is about understanding ourselves and knowing what pushes our buttons and why.

Self-awareness is about understanding ourselves and knowing what pushes our buttons and why.

Our past and our self-image play a large part in how we choose to interpret other people’s behaviour. More importantly, it also determines the way we act and the effect we have on others.

Mindfulness and understanding our emotions

Have you ever driven to work and, when you’ve arrived, cannot remember your journey? Or spent a morning serving customers and have difficulty later recalling what happened? Being on automatic pilot reduces our conscious engagement with what we are doing and there are risks attached. You don’t want to be in front of a driver on automatic pilot, nor to be served by someone who is not paying attention to what you need.

But being in the ‘mindless’ state of automatic pilot opens you up to other problems. You can become prone to old habits and behaviours, perhaps leaving people feeling you aren’t interested in them. Events and situations around you can trigger old feelings and sensations which become barriers and make your mood worsen. And we can fail to notice important signals from the people we are dealing with, which suggest we had better do something differently and straight away.

By becoming more aware of our thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations as they happen, we are creating the basis of greater freedom and choice in how we act and the opportunity to be more responsive to others. We don’t have to go into the same habits or mental tramlines which have caused problems in the past and we can choose to act differently – perhaps building more effective relationships or coping with stresses better.

What this means, of course, is that we may also need to develop another dimension to our problem-solving approach. Most of us have developed, to a greater or lesser extent, a set of critical thinking tools to fix problems. Analytical thinking, problem-solving and judgement are vitally important for an emotionally intelligent person. But problems in relationships, with emotions or with our own unconscious reactions to things, may not respond in the same way as a logistics or resourcing problem.

So what extra skills do you need to deal with people in a mindful or self-aware manner? Try reflecting on your own experience:

When you are in a discussion that you find difficult, when do you become aware of the following? Give yourself a score between 1 and 5 (1 = immediately, 5 = days later, or not at all).

When you are in a discussion that you find difficult, when do you become aware of the following? Give yourself a score between 1 and 5 (1 = immediately, 5 = days later, or not at all).

Recognizing the emotions you experience _____

The need to relax your body when you feel tense _____

How agitated you have become _____

The need to do something about the stress you feel _____

The need to communicate empathy _____

That others are not sharing your ideas and goals _____

The need to gain others’ commitment _____

How positive or negative you are being _____

The need to change course to develop motivation _____

The need to show your sense of humour _____

How well did you do? The most important aspect of the exercise is whether you are conscious of what you are feeling, as it happens. So if you scored lots of 5s you are like many people – doing things and reflecting afterwards. You need to develop your sensitivity about what’s happening now so you can respond there and then. Problems of unclear goals are best picked up straight away. When people are feeling uncertain or vulnerable, they need empathy then, not later.

Mindfulness means paying attention on purpose to what is happening in the present moment, without judging whether it is right or wrong. It emphasizes a collaborative way of working and draws on your listening skills. You also need to control your own emotions, so you can ‘hear’ what’s going on.

Part of mindfulness is knowing what you are feeling as it happens. Being able to give the emotion you experience a name is not some touchy-feely idea about sensitivity. Naming it involves consciously thinking about what is happening and choosing how to react. It gives you the capacity to both register its impact (which engages your limbic system) and also trigger control through greater involvement of other parts of the brain (cognitive structures).

This balance of thought and emotion gives you more control of the feelings you experience by engaging different structures in the brain. Mindfulness is an important element in emotional intelligence because it increases awareness and provides better control. It lets you know when your approach to dealing with others is getting skewed.

Read the list below and think about whether you tend to do these things. If you do, how frequently does it happen?

Read the list below and think about whether you tend to do these things. If you do, how frequently does it happen?

- Unconsciously ignore or push feelings, problems or difficulties out of my mind.

- Behave in ways that do not match the way I really think or feel.

- Become childlike or defensive.

- Rationalize away things that make me feel bad or unsatisfied.

- Take out my feelings on other people.

- Represent my own thoughts or feelings as the thoughts or feelings of others.

Describing your emotions

As mentioned above, being able to identify and name your emotions as they arise is an important part of mindfulness.

If you can find words to describe how you feel at the time, and (even better) what’s causing it, you will automatically become more sensitive and aware. Doing this will provide options for you:

- You may decide that you do not want to feel that way.

- You may decide that your feelings are about things in your past rather than the situation at hand.

- You may begin to think, more tangibly, what it is that others have done to make you feel this way.

- You may begin to think about other people’s feelings too.

When we think about our own feelings, we can often gauge how strongly we feel them by our choice of words.

The list below illustrates the wide variety of words people use to describe emotions; all these terms are used to label the emotions arising from just one feeling – confusion. Note the way the strength of feelings is expressed by using different words:

Strong feeling: Baffled, chaotic, confused, flustered, rattled, shaken up, startled, stumped, stunned, thrown, thunderstruck, trapped.

Medium feeling: Puzzled, blurred, disquieted, foggy, frustrated, misled, mixed up, perplexed, troubled.

Slight feeling: Distracted, uncertain, uncomfortable, undecided, unsure.

Researchers differ about whether there is a definitive list of emotions and whether some are more fundamental than others. Either way, with such a wide selection of terms, it is easy to see why defining emotions can be difficult. But being able to put a name to the feelings you experience helps you to stay in control of yourself. Choosing and using words to describe how you feel at any given point actually helps to engage different parts of the brain from those primarily used for emotion and reaction. (There is more information about this in Chapter 7, ‘Emotional Intelligence and Health’.)

Try to think of what’s underneath your feelings too. For example, a feeling of being annoyed might actually result from a feeling of inferiority: ‘I am irritated when my boss uses long words. I use straightforward words. He makes me feel inferior. It’s not fair, my ideas are as good as his.’ Naming your underlying feelings can also help you to understand yourself and what you might need to keep in control.

The emotional chain

To understand the process that leads to the way we feel and react, think about the following scenario:

You are walking through an unlit park late one night. You hear footsteps behind you. You notice your heart begins to beat faster and you begin to tremble. Your breathing quickens and you are aware of the dark shadows moving near you. You just know that something is about to happen. You are feeling frightened and begin to run …

Four mental and physiological processes were involved in that situation:

Arousal Interpretation Stimulation Behaviour

What was the order in which you think they might have happened?

There are several well-known ideas about the process involved in generating feelings and emotions. In the main, they describe a sequence which involves noticing (sometimes very small) things which trigger thinking about their significance or meaning. Depending on whether the meaning is perceived as positive or negative, changes in brain chemistry alert the body for any physical activity which may be necessary – for example in the situation described above, the ‘fight or flight’ needed for survival. We notice our bodies as they change.

It is at this point that we become aware of feeling something – curiosity or fear, happiness or irritation – linked to the physical change. This knowledge in turn generates further thinking about what to do and how to react.

If you chose stimulation followed by interpretation, then arousal and behaviour, your answer would agree with mainstream ideas about how emotions influence our reactions.

Tuning in to how you are feeling

Tuning in to how you are feeling

There are many things going on right now, stimuli surrounding you in your immediate environment, sensations in your body, and thoughts and feelings in your mind of which you probably were not consciously aware.

Have you been paying attention to the room you are in? Stop for a moment and close your eyes when you reflect on the following questions:

- What is the temperature?

- How does it smell?

- What are you sitting on?

- Is it comfortable?

And your body:

- Do you have any aches or pains?

- Are your muscles tight or relaxed?

- Is your stomach pleasantly full or is it painfully empty?

Reflect on the following questions:

- What thoughts have been occupying your mind in the last couple of minutes?

- Where has that taken you outside the room?

Becoming aware of and understanding your feelings

The self-awareness exercise above is intended to make you think about how many triggers there are for our feelings, thoughts and perceptions. But self-awareness is more than paying attention thoroughly. It is changing how we pay attention.

Most people would say that they pay attention to things around them – and of course we do, if only to get things done that we need to. Usually we perceive things through a sort of ‘tunnel vision’. If we have been chronically unhappy, for instance, we tend to see things through that prism. And with a particular problem in mind, anything that doesn’t immediately seem relevant drops out of our field of view.

Real awareness asks you to turn a switch, focusing on ‘What’s going on inside me at this moment?’ It means suspending judgement for a time and putting your goals in the back seat while you describe what is actually going on rather than what you think should be.

Being open means turning off the switch marked ‘autopilot’ in which we tend to operate for long periods. This gives you a more vivid sense of the situation and helps you notice the clues which tell you about how other people are feeling or reacting to you. You experience things you may never have noticed before and become more aware of whether your usual reactions are appropriate. Mindfulness can transform the way you understand situations and give you many more options for how you react to them.

Accurate self-assessment involves:

Accurate self-assessment involves:

- Knowing your own strengths, weaknesses and limitations

- Being open to what is happening around you

- Valuing feedback

- Having a sense of humour and perspective

- The capacity to reflect and to learn from experience

- Being open to change.

Being open to new experience

In the last section, we began to identify both the effect and the risks of operating on autopilot. Self-awareness helps you to operate in a conscious, non-judgemental, switched-on way. We also need to limit autopilot behaviour for another reason – doing so opens the way for us to experience something we haven’t been aware of before.

Our reactions are often based on significant events and interactions of the past; they are models of behaviours, feelings and options constructed for us to draw on to deal with new situations. A significant part of this ‘map’ is developed during our early lives and is largely determined by the people and situations we have experienced. We often act from the map rather than the reality of the situation. Mindfulness, being aware of what is going on around you, helps to stop you going on to autopilot and opens the way for you to see new possibilities. We can change old behaviours that didn’t achieve what we wanted, or find different ways to react that will make others respond positively. We can also respond in ways that make us feel better about the overall situation.

A sense of optimism

Would you describe yourself as an optimist or a pessimist? People differ in how they describe themselves because they have different expectations about future events. Take the achievement of personal goals and the benefits you will accrue. Optimists are generally confident about the future and are characterized by a belief that outcomes will be positive. Pessimists have a generalized sense of doubt, are often hesitant and perhaps cynical about future outcomes, perhaps believing that ‘no expectation means no disappointment’. Past disappointment can lead to fearing the future.

Optimism is better than pessimism

Research in the field of positive psychology has found many advantages to taking an optimistic perspective, such as:

- Optimists adapt better when they experience negative life events, for example they have better survival and/or recovery rates for coronary bypass surgery, bone marrow transplants, breast cancer and Aids.

- They experience less distress when dealing with difficulties in their lives, resulting in lower rates of depression and anxiety.

- Optimism is a valuable framework when coping with problems. It is conducive to humour, identifying possibilities and visualizing the problem differently. As a coping skill it enables you to accept the inevitable and learn for future events. It is a more effective coping skill than pessimism.

- Optimists stick their head in the sand less than pessimists, perhaps surprisingly. They respond to health warnings more quickly and catch serious problems earlier than pessimists (who often try to distance themselves from problems).

- Optimists appear to have greater ‘stickability’ than pessimists, who (perhaps anticipating failure) give up more quickly.

- Optimistic assumptions tend to provide more flexible responses.

Is there a downside?

Optimists can sometimes downplay risks with the result that they are more likely to participate in dangerous activities. I’m not sure how many pessimists are likely to go bungee jumping! Perhaps we would be better off with a mix of pessimism and optimism in this regard. In dealing with others, however, emotional intelligence is much more a characteristic of optimists than of pessimists.

There are a number of strategies to counter pessimistic styles of thinking. A key strategy is to work on the way we explain the causes and influence of positive and negative events.

The three explanations for optimism

There are three explanations which illustrate the way optimists differ from pessimists; they relate to whether the events are construed as permanent or temporary, global or specific and caused internally or externally. The following examples illustrate the different outlooks they generate:

Setbacks are seen by low-optimism people as:

- Permanent

- All-pervasive

- Personal.

They are seen by high-optimism people as:

- Temporary

- Specific to the situation

- Caused by external events.

Success is seen by low-optimism people as:

- Temporary

- Specific to the situation

- Rooted in external factors.

It is seen by high-optimism people as:

- Permanent

- Having widespread significance

- Deriving from the people involved.

Long-term issues (such as difficulty making presentations) are explained by low-optimism people as:

‘I always find presentations difficult.’

They are explained by high-optimism people as:

‘I sometimes find presentations a bit tough.’

Problems in handling awkward situations are explained by low-optimism people as:

‘I dislike handling awkward situations.’

They are explained by high-optimism people as:

‘I didn’t handle that situation well.’

Personal achievement (such as sales success) is explained by low-optimism people as:

‘This is an easy product to sell.’

It is explained by high-optimism people as

‘I’ve really been putting in extra effort.’

Positive psychologist Martin Seligman argues that we can acquire ‘learned optimism’, mitigating the negative impact of a more pessimistic attitude by challenging the way we think about things.

Seligman believes that psychology should explore strengths as well as weakness. Having worked extensively with depressed patients who had acquired what he describes as ‘learned helplessness’, he went on to develop his concept of ‘learned optimism’. In research undertaken in the insurance industry, Seligman and his colleagues found that optimists who were employed as new salesmen sold 37 per cent more insurance in their first two years than pessimists.

When the company then hired a special group of individuals who scored high on optimism even though they did not have the normal experience required in sales jobs, they outsold the more experienced pessimists by 21 per cent in their first year and even more in the second.

Challenging your own pessimistic thinking means asking yourself:

- What evidence is there for your negative thoughts?

- Is your pessimistic thinking related to past events? Have things changed now?

- Can you find an alternative explanation or other evidence for the situation?

- Even if there is no positive explanation, does it really matter?

- What are the implications of the situation?

- Is it really damaging?

- And if you can’t find an optimistic explanation for the cause, which perspective would be more helpful for your mood?

Optimism is often a consequence of EI. It is about, when things go wrong, tending to see the causes as specific, temporary and linked to factors outside yourself.

Optimism is often a consequence of EI. It is about, when things go wrong, tending to see the causes as specific, temporary and linked to factors outside yourself.

Optimism involves accurate self-awareness and the ability to be take control of anxieties and frustrations – and to manage interactions in a way which lessens stress rather than succumbs to it.

Pessimists are less likely to have these characteristics. Unlike optimists, they also tend to see causes as widespread or even universal, permanent and often resulting from internal weaknesses.

There’s more on the benefits of optimism and empathy in Chapter 5, ‘EI and the workplace’.

Self-esteem and confidence

Everyone holds opinions about the type of person they are and how they relate to others. These opinions are at the heart of your self-esteem and they affect how you feel about and value yourself.

Self-esteem is not static or fixed. The beliefs you hold about yourself can change throughout your life and events like redundancy or a relationship breaking up may give your confidence a huge knock. If you have high self-esteem, you will generally see yourself in a positive light. High self-esteem can help you bounce back, acting as a buffer increasing your resilience. Someone with low self-esteem will often have built up negative beliefs about themselves, focusing on things they see as weaknesses, and experiencing feelings such as anxiety as a result.

The types of belief which have developed, often since childhood, make the difference between high and low self-esteem. If the beliefs are mainly negative, there is evidence that they can put you at a higher risk of mental health problems including depression and mood disorders. Low self-esteem and confidence are closely related to your mood and self-image, so it is important to realize that beliefs are only opinions, they are not facts. They can be biased or inaccurate, and there are steps you can take to change them.

If you feel that working on your self-esteem might be useful, you could try keeping a thought diary or record for a few weeks. Write down details of situations, how you felt, particularly when your self-esteem was low, and what you think your underlying belief was. As you identify the core beliefs you hold about yourself, you can begin to challenge and change them.

If you feel that working on your self-esteem might be useful, you could try keeping a thought diary or record for a few weeks. Write down details of situations, how you felt, particularly when your self-esteem was low, and what you think your underlying belief was. As you identify the core beliefs you hold about yourself, you can begin to challenge and change them.

What causes low self-esteem?

There are no universal causes of low self-esteem because your development so far is likely to have been a highly individual process. Your personality and any inherited characteristics will play a part and your experiences and relationships are important. Negative experiences in childhood are often particularly damaging to self-esteem. In your early years your personality and sense of self is being formed, and harmful experiences can leave you feeling that you are not valued or important. You have not had a chance to build up any resilience, so this negative view can become what you believe about yourself.

Negative core beliefs about your intelligence, appearance and abilities are often formed by experiences such as the following:

- Having your physical and emotional needs neglected in childhood

- Failing to meet the expectations of your parents

- Feeling like the ‘odd one out’ at school

- Being subject to abuse – sexual, emotional or physical – and the loss of control associated with this

- Social isolation and loneliness.

Poor self-esteem is also fed by a vicious circle of experience: you learn to expect the worst and when you think it is beginning to happen, you react badly because at the back of your mind, all the time, you are feeling anxious. You might shake, blush or panic, or behave in a way that you think will keep you ‘safe’, e.g. shy or vulnerable people who do not go to social events on their own. This ‘security behaviour’ is likely to confirm the negative core beliefs you have about yourself. This adds to your store of examples, leaving you feeling you have even less chance of coping next time. It is a cycle that might seem unbreakable.

Strengthening self-esteem

Strengthening self-esteem

The following tips can be really helpful. Keep checking on them during the day. They should keep you positive and engaged in boosting your self-esteem:

- Stop comparing yourself to other people.

- Don’t put yourself down.

- Get into the habit of thinking and saying positive things about you to yourself.

- Accept compliments.

- Use self-help books and websites to help you change your beliefs.

- Spend time with positive, supportive people.

- Acknowledge your positive qualities and things you are good at.

- Be assertive; don’t allow people to treat you with a lack of respect.

- Be helpful and considerate to others.

- Engage in work and hobbies that you enjoy.

We have seen that your self-esteem comes from core beliefs about your value as a person. If you want to increase your emotional intelligence, you need to challenge and change negative beliefs. This might feel like an impossible task, but there are a lot of different ways that you can do it. A critical issue is having a strong sense of purpose and direction, as explained in the next section.

Purpose and direction

People with strong emotional intelligence are often seen as independent characters, not afraid to question what is happening and with a value set which they are happy to share and discuss. Similarly, they have a clear sense of direction, which they are also upfront about.

What do you want to achieve in your life or your career, and what are your plans for achieving it?

What do you want to achieve in your life or your career, and what are your plans for achieving it?

With that in mind, think about the following questions:

- What sort of reaction do you think is likely if you are seen by others as passive or indifferent?

- What do you consider the consequences might be if you were unable to voice views that are different or challenging, perhaps unpopular even?

- And what sort of reaction might you receive if you are seen by others as indecisive or you freeze whenever things are uncertain?

Answer: You are unlikely to achieve respect or impact on others very easily!

The self-knowledge aspect of emotional intelligence is concerned with understanding the way we try to gain the trust of others and influence them. Good self-awareness includes knowing the strengths and weaknesses you have – the behaviours you are skilled in and those you need to develop to become more effective. Crucially, it involves thinking carefully about what you want to achieve and whether you can balance your drive to organize things (systems, procedures and tasks) with the importance of the emotional side of the enterprise.

Acting purposefully

Knowing your strengths and weaknesses can be a major step in both personal confidence and effective communication. Knowing where you stand and having a clear set of values or beliefs are also pre-requisites for confidence and impact. The sense of grounding and self-confidence that these qualities can give you was described many years before emotional intelligence was known as such, by Pitt the Younger in his description of what a committed minister of the crown needs to be. Pitt said, ‘I like knowing where I stand, being able to be honest about what I think, comfortable with how I feel and genuine about what I say … When you go into a bear pit like the House of Commons you may have a vision for the future but you feel as though you have both feet planted on the same ground that ordinary people walk.’

A sense of purpose, driven by values, is a powerful force. The impact it can create is illustrated by Japanese ceramics technology manufacturer Kyocera. Its founder, Kazuo Inamori, believes that ‘the active force in any aspect of the business is people … they have their own will, mind, way of thinking. If they are not motivated to challenge, there will simply be no growth, no gain in productivity, no technological development.’ His vision was to tap the potential of his staff with a corporate motto: ‘Respect Heaven and Love People’. The impact that his beliefs have created, far from being overly romantic in a business world, has seen Kyocera going from start-up to £2 billion sales in 30 years, borrowing almost no money and achieving profit levels which are the envy of bankers worldwide.

A sense of purpose, driven by values, is a powerful force. The impact it can create is illustrated by Japanese ceramics technology manufacturer Kyocera. Its founder, Kazuo Inamori, believes that ‘the active force in any aspect of the business is people … they have their own will, mind, way of thinking. If they are not motivated to challenge, there will simply be no growth, no gain in productivity, no technological development.’ His vision was to tap the potential of his staff with a corporate motto: ‘Respect Heaven and Love People’. The impact that his beliefs have created, far from being overly romantic in a business world, has seen Kyocera going from start-up to £2 billion sales in 30 years, borrowing almost no money and achieving profit levels which are the envy of bankers worldwide.

Emotional intelligence underpinned the vision which drove Inamori and all his staff. The vision was that the urge to build something – to create – resides in us all. The juxtaposition of vision and current reality generated what Kyocera describes as ‘creative tension which everyone enjoys trying to resolve’. The emotionally intelligent approach adopted was to ensure that everyone could share in the vision of trying to create. Senior management ensured that controls, limitations and constraints were kept to the minimum possible.

What is the sense of purpose which drives you in your work or personal life? Does your vision fill you with excitement and confidence? How well do the other people you relate to share your beliefs and excitement?

What is the sense of purpose which drives you in your work or personal life? Does your vision fill you with excitement and confidence? How well do the other people you relate to share your beliefs and excitement?

Expressing emotions

How do you feel when you ask someone to do something for you, which they might refuse? For many of us, this is a very difficult verbal exercise. We need to ask in such a way as to hopefully get the other person to comply, which involves ensuring the request is clear, specific and direct. On the other hand, if we are too direct, we may offend the person and reduce the likelihood of co-operation.

How we go about it is important. You might think that things get easier if the person is in a good mood. It seems sensible, but studies also suggest that our approach is more often determined by our own mood. Happy people interpreted situations more optimistically than others. They expressed themselves in more direct, sometimes impolite ways (‘Just do it, will you!’). Less happy people used more formal, polite forms of request. And in complex situations with more demanding and difficult requests, this ‘mood effect’ was magnified.

Emotional intelligence requires an awareness of how emotion influences our thinking, judgement and interpersonal behaviours. In some situations we may need to deal with sensitive issues, in others with sensitive people. Our own emotion affects how we think, make decisions and communicate with others. In some cases, the situation may require us to talk about people’s feelings or to confront the way in which they affect us. Communicating about emotion is not necessarily straightforward.

Talking about feelings

Talking about feelings

On a scale of 1–10, how comfortable do you consider yourself to be talking about your own emotions (where 1 means you find it incredibly difficult, 10 means you do it all the time)?

Using a similar scale, how easy do you find discussing other people’s emotions?

What is the worst situation you could imagine in which you would have to discuss emotions?

What is the most comfortable situation you can imagine in which to discuss emotions?

In the day-to-day situations you experience, how aware are you of the influence that your own emotions play?

The effect of emotions on thinking

Emotions have a multi-faceted impact on everything we think and do. Any decision you make may be driven by rational analysis of evidence, use of logic and analysis of data, but that isn’t all. Most decisions also involve personal values, the lessons of your experience, the potential impact your decision may have on others. If there are conflicts between thinking and feeling, it’s usually the things we understood emotionally that people respond to. Our capacity to rationalize emotional decisions as logic is testament to the power of our emotions.

Moods

Unlike more intense emotions, moods are relatively low-intensity, diffuse and potentially pervasive states of mind. Everyday moods, whether good or bad, tend to colour our levels of optimism, relationships, achievements and pretty well everything we do. Their effect on how we might behave also can be more insidious, subtle and long-lasting.

For example, underlying low mood for many people can trigger stress responses in which they:

- Unconsciously push anxiety-producing information out of their own awareness

- React in a way contrary to how they actually think or feel

- Go back to an earlier stage of their development, perhaps behaving in a very dependent or childlike way

- Convince themselves that there is an acceptable reason for their behaviour when the real motive was unacceptable

- Redirect behaviour or emotion to a less threatening object (taking out frustrations, for example, on innocent objects or people)

- Project their own, often unacceptable, attitudes, perceptions, beliefs or feelings unfairly on to others.

Both our moods and our more intense emotions create filters through which we communicate and manage our relationships with others. When we act on autopilot, the stress reactions listed above help to remove short-term pressure but can create more significant problems, particularly for the individual involved. If the mood or emotional state continues, it can have a serious effect on the way we process information, see opportunities and perceive risk. It can become self-defeating and reinforce underlying negative emotional ‘schemas’ or patterns which, in turn, filter the way we perceive and process information.

Underlying patterns often found in people with low mood (more so when more severe depression is identified) are often described as ‘life scripts’. These may include beliefs such as ‘I need to depend on someone stronger than myself’; ‘I can’t change anything’; ‘Only bad things happen to me’.

Positive and negative emotions and outlook

People experiencing positive emotions:

- Are likely to think well of others

- Expect to be accepted by others

- Are positive about their aspirations

- Are not afraid of others’ reactions

- Work harder for people who demand higher standards

- Feel more comfortable with talented people

- Are comfortable defending themselves against negative comments by others.

Whereas people experiencing negative emotions:

- Are more likely to disapprove of others and themselves

- Expect rejection

- Have lower expectations and are more negative

- Are sensitive and perform poorly under scrutiny

- Work harder for uncritical, less demanding people

- Feel threatened easily

- Are more easily influenced and find defending themselves difficult.

As we have said before, self-knowledge, for emotionally intelligent people, helps us to understand ourselves and our way of thinking. We need to be aware when some of these problems are affecting us and the way they may skew our thinking. We need to be vigilant of any tendency towards:

- Over-generalizing

- Filtering out important things

- Discounting positives

- Absence of balance (‘all or nothing’ thinking)

- Jumping to conclusions

- Magnifying or minimizing problems

- Being judgemental

- Stereotyping people and situations

- Inability to detach ourselves from personal views.

Stress

Your reaction to stress

Coping with changing markets, juggling tasks, meeting difficult targets and dealing with difficult people – these are common difficulties which people have to cope with. Outside the workplace, relationship problems, bringing up children and healthcare issues need to be handled. When people believe they can’t cope, stress is the result. It is another example of the pervasive influence emotions have on our thinking and behaviour. Emotionally intelligent people need to find ways of handling it, both for themselves and when the symptoms are shown by others.

A questionnaire included in Chapter 7, ‘Emotional Intelligence and Health’, can help you to form an idea of how prone to stress you are – see page 201.

Extreme stress and anxiety produce what eminent psychologist Jerry Suls calls a dangerous ‘neurotic cascade’ which can seriously limit your ability to use your emotional intelligence. The neurotic cascade refers to the destabilizing effect of negative thoughts and negative feelings clashing together to diminish your ability to cope. In this state, minor problems become magnified out of all proportion. Over-dramatizing negative outcomes – or ‘awfulization’ – and questions about coping are sometimes complemented with mood changes. In turn, these result in skewed thinking and further stress. Emotionally intelligent individuals recognize these problems and use effective strategies to tolerate stress. Effective coping strategies enable you to judge what a tolerable level is for yourself, and also for other people.

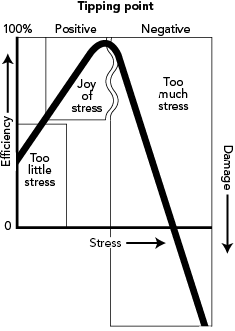

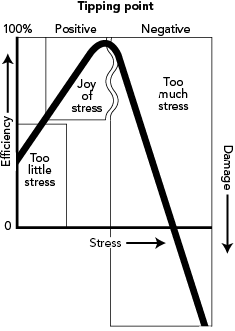

But some people seem to thrive on this type of situation. Look at the diagram below. Moving from left to right, the bold black line shows the impact of an increasing amount of stress. To begin with, the amount of stress being experienced is not enough to stimulate effective performance. Sometimes people find themselves in situations which give them insufficient stimulation or challenge to be worthwhile.

There comes a point shortly after that in which the optimum amount of stress is reached – the buzz of being busy, the challenge of a stretching but achievable target, the satisfaction of getting a new job under your belt.

Somewhere, and it differs for individuals, there comes a tipping point at which targets become unachievable, challenges just can’t be met and the stress which was enabling becomes too much. As the amount of stress experienced increases even more, it becomes disabling and increases the risk of physiological damage. Being in this part of the model for prolonged periods of time increases the correlation between stress, depression and the immune system, and serious damage can occur.

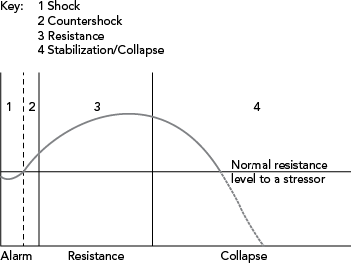

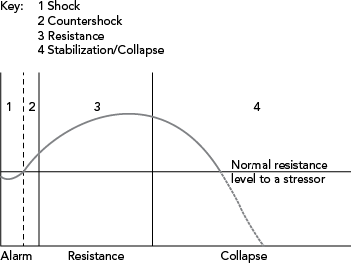

Stress is a physical symptom, and not a root cause of problems. The situation (or stressor), in which challenges become unmanageable, causes the so-called ‘fight or flight’ reaction; the brain’s limbic system activates the body’s resistance to threat through the distribution of neurochemicals and hormones. The diagram below illustrates the process.

The vertical axis on the chart represents the level of physical tension experienced when the body is under attack, while the horizontal axis represents time. The flat horizontal line in the middle represents the body’s normal level of resistance to stress. The curved line shows the increase in tension (measured by blood pressure, heart rate, vascular change, etc.) that takes place under stress, before, usually, stability is re-established and the body returns to normal.

The body’s reaction is made up of the following stages:

1. Shock: Realization of the nature of the situation and its demands creates an instant shock, creating confusion, uncertainty and a loss of visual and cognitive focus. At this stage, people tend to react automatically, although an alternative in some severe situations (particularly facing aggression) is that people freeze, becoming unable to respond.

2. Counter-shock: Upon realizing that we are at risk and may not be able to cope, the fight or flight response is triggered and catecholamines (including adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine) are released.

3. Resistance: The catecholamines affect the body in a number of ways, increasing blood flow, oxygenating the muscles, evacuating the digestive system, increasing visual and aural acuity, and increasing sensitivity to temperature. All of this is geared towards making us better able to combat risk.

4. Stabilization/Collapse: As the risk or threat abates the body should return to its normal state, controlled by the actions of our ‘parasympathetic’ system – a branch of the autonomic nervous system designed to re-establish equilibrium. However, depending on the level of the stress reaction, or if the fight or flight mechanism is being triggered too frequently, this stage can result in collapse rather than stabilizing at the normal resistance level. This creates a risk of tissue and organ damage, which can result in digestive tract problems, ulcerative colitis, triggering or worsening depression and cardiovascular disease, and speeding the progression of HIV/Aids.

But why are some people apparently immune to stress whilst others in the same situation experience disabling physical and psychological effects?

The two things that cause the sympathetic system (fight and flight response) to activate are:

- Firstly, the stressor itself: these are the characteristics of a situation that create anxiety, like pressure, excessive demands, personal threat or excessive risk.

- Secondly, the judgement that is made by the individual about the threat, based on their personality and experience: whether or not they feel able to cope. The immediate cause of stress is the perception of being out of control, being unable to prevent what may be seen as untoward consequences taking place.

The difference between coping and not coping is in large part due to the judgement of threat – two people faced with the same situation evaluate it differently. Another factor which affects the severity of stress is the coping behaviour used. It is important to recognize that not all options for coping with stress are helpful. Resorting to alcohol, smoking and excessive eating, for example, may make you feel better for a time but eventually do harm. This is adapting your behaviour to the stress but in a harmful way (so-called maladaptive response). Relaxing is often advocated – though not easy to do if you are coping with emotionally charged situations. Physical exercise and confronting problems are also often recommended as more positive adaptive behaviour.

People make choices about how they deal with stress, finding ways of coping, which, if removing the stressor isn’t possible, enable them to adapt their behaviour to retain a positive perspective: this is vital both for working with others and for securing your own health and welfare. Some examples of both positive and negative adaptive behaviours are shown below:

|

Stressor

|

Adaptive behaviour

|

|

Overwork

|

Delegates some responsibility

|

|

Uncertainty of policy/situation

|

Finds out what policy/situation is

|

|

Poor working relationship

|

Raises issue with colleague and negotiates better relationship

|

|

Poor career progression

|

Leaves organization for another

|

|

Organization versus family

|

Negotiates with boss more family time

|

|

Role ambiguity

|

Seeks clarification with colleagues or superior

|

|

Stressor

|

Maladaptive behaviour

|

|

Overwork

|

Accepts overload and general performance deteriorates

|

|

Uncertainty of policy/situation

|

Guesses inappropriately

|

|

Poor relationship with colleague

|

Attacks colleague indirectly through third party

|

|

Poor career progression

|

Loses confidence and becomes convinced of own inadequacy

|

|

Organization versus family

|

Blames organization/individuals for problems/discontent

|

|

Role ambiguity

|

Becomes reactive/uncertain/sows confusion

|

2. Managing your emotions

Our view of ourselves, our confidence, self-esteem, sense of purpose and awareness of the way we tend to react to things provides the basis for self-management, i.e. the ability to stay flexible and behave in a positive and effective way, appropriate to the situation you are in.

Self-awareness is one part of the balance between yourself and others which is at the heart of emotional intelligence. It provides an important insight into your needs and motivation when you are dealing with others. On its own, however, simply knowing how you feel does not lead to achieving your hopes and goals – in fact, it can actually cause you more problems than you might think. Take Janet, for example:

Janet is a fairly sensitive individual who has been experiencing some major life problems. She thinks of herself as relatively self-aware and in the situation described in the flow chart on page 73, Janet is probably thinking a lot about herself. What do you think the effect of this would be?

Janet is a fairly sensitive individual who has been experiencing some major life problems. She thinks of herself as relatively self-aware and in the situation described in the flow chart on page 73, Janet is probably thinking a lot about herself. What do you think the effect of this would be?

As we go through life, the challenges we face and the successes and goals we accomplish (or not) usually give us cause for reflection. Janet was strongly aware of what she wanted and strongly affected by the emotion of the current situation. The flow chart illustrates how her emotions have affected her thinking.

The impact has become disabling and negative in part because Janet has been going through the process of reflection which we call ‘rumination’. It usually happens as a result of being very aware of the gap between what we would like and what is happening in reality. In her case, she will be reflecting on her unhappiness, the negatives in her present situation, how things might have been, and a wide range of faults, blame and causal factors for the problems she is experiencing. Usually, rumination is accompanied by a reinterpretation of events, and adding negatives to the person’s own actions (‘he left because she wasn’t good enough’).

The gap between aspiration and current reality can lead to rumination and negative thinking. Imagine for example that you are going to a party but feel tired and out of sorts. As time goes on, you also become conscious of something else: how by going to parties you should be feeling great but in fact, are not. Think how you would feel at that point. Many people say they would feel worse than ever.

This is actually a very serious problem because, over a prolonged period of time, rumination diminishes optimism, encouraging negative thinking as the preferred response. Ruminators have trouble getting upsetting thoughts out of their minds; perhaps as a result, they seem to be motivated to avoid unpleasant feelings by trying to rationalize (or ‘reason away’) anything which seems uncertain or uncontrollable. It is a state of mind which is very self-critical. And being absorbed with what’s wrong in a situation, rationalizing things away and being self-critical is a potent recipe. Research links these factors to the tendency among ruminators for procrastination and failure to act promptly in dealing with interpersonal problems.

Perhaps one of the best ways to avoid rumination is maintaining your awareness of the here and now, together with developing an independent, confident and optimistic outlook. These are the characteristics which allow you to take an assertive approach, dealing with problems as they arise rather than leaving them to grow and take on greater significance. A clear sense of purpose helps too. We know that people with strong values are better able to withstand stress and it seems that being purposeful plays a similar role. Controlling the stress reaction, mindfulness and assertiveness limit the power of rumination.

How ‘in control’ do you feel?

Every day we are faced with situations in which we experience impulses, often triggered by things that we want or desire. This may be an impulse to interfere with how someone is doing a piece of work – thinking we would do it differently or better – or maybe letting rip about how we really feel about something that was done. Alternatively the impulse might be about buying those Louboutin shoes despite the size of your credit card bill. Usually, a lack of control is part of a wider pattern of behaviour, often shown by problems like anger control, difficulty controlling weight or substance abuse.

The ability to control impulses, or more specifically to control the desire to act on them, is primarily about deferred gratification. Being impulsive creates problems in relationships and limits the rational thinking needed to deal with others.

Making emotions manageable

Making emotions manageable

- Breathe deeply.

- Take a break, make some coffee, go for a short walk.

- Use the ‘thinking’ part of your brain to exert influence on the emotion-creating part.

- Project into the future – how significant will this situation be next week/month/year?

- Change the variables – if someone else were involved, would you still feel the same? If it happened at a different time, would it still be so upsetting?

- Minimize negative automatic thinking – were there no redeeming features at all? Am I speculating about something which may never happen? Am I blaming myself for something I had no control over?

- Three-minute stress control – try a breathing exercise to reduce the effect of stress.

- Model a new behaviour – think of someone you value or admire. How would they behave in this situation?

- Use collaborative language to encourage others to resolve the situation: ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘together’, ‘share’, etc.

- Adopt a collaborative approach – what will encourage others to help – being respected? Being helped? Being positive? Being clear? Being valued?

Your emotional intelligence helps you to become aware that behaviour is rarely random. We need to understand what motivates others and how to live or work with them comfortably. If intense emotions, such as stress, frustration or anger are not controlled, inappropriate behaviour can damage relationships.

Controlling outbursts

The first thing you say when you feel angry is usually the worst thing you could say. It takes approximately six seconds from the moment a powerful negative emotion is felt to the time the adrenalin begins to abate. That’s about how long you should wait before responding when you’re really angry. If you can, simply count to ten; distract yourself.

Controlling impulsive reactions

Controlling impulsive reactions

- Separate the issues involved from the people problems.

- Use distraction and time-outs to keep you cool.

- De-escalate when others get emotional.

- Solve underlying problems by being supportive, analytical and using your listening skills.

Imagine being three or four years old, and being asked to sit in front of a table with your favourite sweet on a plate. If you like, you can eat the sweet straight away. However, if you wait, alone, for fifteen minutes without touching it, you can then have two to eat whenever you like! This was the basis of a research programme at Stanford University. The children responded differently: those who were able to leave the sweet actively found ways to distract themselves, including playing games with their fingers, covering their eyes, singing and talking to themselves. Those who were unable to control themselves did not try distraction: they focused on the object of their desire and ate the sweet within minutes, or in some instances seconds.

Fourteen years later, the children who had been able to resist temptation were more academically successful, socially and emotionally adept, and better able to cope with stress. They pursued challenges rather than giving up when something became difficult; they were seen as independent, confident, trustworthy and prone to showing initiative. And they were all still able to delay gratification for the sake of achieving their goal.

The children who had succumbed to the temptation and had eaten the sweet frequently seemed to be troubled individuals, believing themselves to be ‘unworthy’, resentful about ‘not getting fair shares’, and were easily upset by stress. Almost without exception they were less successful in their studies and reports from people they knew suggested they were also prone to distrust and provoking arguments. Fourteen years later they were still unable to delay gratification, or control their impulses.

Being able to control impulses involves emotional intelligence: being aware of the situation you are in, evaluating the possible consequences of simply satisfying your own wishes immediately, and using diversionary tactics to overcome the stress involved in delaying your response.

It is an integral part of Freud’s ‘reality principle’ that achieving your aims can be made more certain if you can stave off the urge to satisfy the impulse immediately and behave in a manner that is suitable for the time and place.

A simple example is that, if we were hungry, without the reality principle we might find ourselves simply snatching food from another person’s hands and forcing it down without any concern either for the other person’s needs or for how we are seen by others.

So diversion is the name of the game. After you’ve taken a few seconds to allow the stressor hormones from the impulse to dissipate, you can respond in an appropriate way. It may mean leaving something until later when you are more relaxed. You might be more prepared to deal with the issue itself, rather than the emotion caused by the people involved. These two factors need separating; if you feel the need to discuss personal issues, choose a time and place when both of you are relatively calm and can discuss things reasonably. In the heat of the moment it is better to focus on the issue causing concern and try to establish options for dealing with it.

If it’s a really heated debate, agree that you take some time out. The chances are everyone is in a calmer frame of mind, more suited to reason. Delays and distractions are a great way to curb impulses so, if you can, try doing something else for a while and plan exactly what action you will take. You will take the emotional heat out of the situation and be able to deal with issues in a more rational and constructive manner.

Do the following statements apply to you? If they do, you are a long way towards being in the collected and analytical state necessary for thinking about the emotions which others are experiencing.

Do the following statements apply to you? If they do, you are a long way towards being in the collected and analytical state necessary for thinking about the emotions which others are experiencing.

- I am able to control my temper and handle difficulties without them affecting my mood or speech.

- Even when emotional, I can speak in a calm and clear manner.

- I can always calm down quickly when I am very angry.

- When I am very happy I rarely go overboard.

- When dealing with problems, my long-term goals are always the thing which guides my response.

- I can take an independent view of things, even when others disagree.

- I demonstrate optimism, no matter how difficult the situation or other people may be.

Emotional self-control helps you to manage those disruptive emotions which we all feel from time to time – being angry, frustrated, anxious, fearful – but also the excesses we are liable to when feeling good turns into euphoria and ‘going over the top’. Euphoric behaviour frequently happens when you feel the need for release – perhaps after a prolonged period of stress or when you experience the relief of something NOT happening.

Emotional self-control enables you to:

- Think clearly and stay focused when others are highly emotional

- Stay composed in difficult moments, giving you the opportunity to stay optimistic and positive

- Keep your impulsiveness under control, or your behaviour when you are feeling anxious or distressed.

Values for working with others

Being able to control yourself in an emotionally intelligent way involves the ability to distance yourself from the situation temporarily, analytical skills to work out how best to accomplish your goals and having a clear sense of purpose. It also involves having positive values for working with others, such as:

Honesty and openness: being true to yourself and your sense of purpose helps others to see you as trustworthy and someone who acts with integrity – even if they don’t like what you do. Demonstrating these aspects of self-control means:

- When you are wrong, admitting your mistake and explaining why it may have happened.

- Confronting behaviours and actions in others when they conflict with your beliefs. Being open about why it is a problem and positive about what else might be done in future helps confrontation to become a useful tool for building relationships, rather than a symbol of aggression and need for dominance.

- Being consistent and acting in accordance with your principles is really what ethical behaviour is about. You recognize deeply held beliefs when people act consistently, even when faced with conflicting emotions.

- Reliability and authenticity: doing what you say and being clear it is what you think is right – not creating a perception that you do whatever is expedient.

Adaptability is a good way to demonstrate to others that you are committed to your goals and sense of purpose. Change and uncertainty can be handled more effectively when people believe that they can influence what is happening. It is when change has both negative consequences and involves a loss of control that people become more defensive and less responsive to others trying to influence them.

- Flexibility in handling change means involving others as much as possible and being clear about options, risks and potential opportunities arising from it.

- The multiple demands which are likely to result raise important questions about coping: the time-management involved, clarity of goals, objectives and roles – and above all what the priorities are. If these are handled smoothly, change can become exciting rather than threatening.

- Different ‘pairs of spectacles’ – how someone sees events needs some thought. Adaptability may involve re-framing the way the situation or people are seen, and taking other perspectives. You need a degree of imagination to see things from others’ points of view – more about that when we look at empathy in the next section.

Conscientiousness is a personal value or quality which is seen by others as a marker both of independence and reliability. Human beings have a remarkable ability to rationalize, to find any number of reasons for doing or not doing something. To influence others, the emotionally intelligent person needs to be seen as someone who takes their commitments seriously and models the behaviour they seek from others. This means:

- Meeting your commitments and holding yourself accountable for getting things done

- Keeping promises. Even where this might be a bit inconvenient, it is vital for sustaining trust.

Resilience

Resilience is a very important aspect of emotional self-management. It refers not only to the ability to keep going in adverse or challenging circumstances, but also the ability to think clearly, choosing appropriate and sustainable ways to react whilst dealing with the feelings involved.

The seminal ideas of Carl Jung explore the different preferences we adopt when we perceive information and make judgements about it. Two of the processes we use are critical thinking (analysing, conceptualizing, applying, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information) and the ‘affect’ or instinctual thinking (emotion, reactions, feelings, values). In the population generally, roughly 50 per cent of people seem to use critical thinking as a preferred way of dealing with life, with a similar number using emotions or affect. These preferences produce very different approaches.

Most people who prefer critical thinking:

- are analytical

- use cause-and-effect reasoning

- solve problems with logic

- strive for ‘objectivity’

- search for flaws in arguments

- think of equity in terms of decisions.

Most people who value instinctual or feeling-based judgement:

- are guided by personal values

- strive for harmony and positive interaction

- search for points of agreement

- want people to be treated as individuals with needs

- use empathy and compassion.

In normal situations, we use both critical and instinctual thinking to some degree, although one tends to dominate. But we need to keep our thoughts and feelings in balance. This means using critical thinking to take active command of not only our thoughts and ideas, but our feelings, emotions, and desires as well. It is critical thinking which provides us with the mental tools needed to take command of what we think, feel, desire, and do.

So resilience involves conscious awareness and the ability to use logical and critical thinking to modify how we feel. Paradoxically, to be emotionally intelligent, we need to ensure that our thinking is not dominated exclusively by emotion.

Emotional intelligence is working on our instincts and thoughts to create a stable and resilient balance for dealing with others.

Emotional intelligence is working on our instincts and thoughts to create a stable and resilient balance for dealing with others.

Willpower

What is willpower? Self-control? Self-discipline? Resolution? Drive? Determination?

We use many different words to describe willpower, a quality or strength which enables you to avoid giving in to things, or keeps you going when circumstances become difficult. A 2003 US study investigated someone’s ability to continue trying difficult tasks and testing their persistence in difficult situations. Research psychologist Roy Baumeister used a number of ideas to define willpower more precisely. He suggested that:

- Willpower is demonstrated through the ability to resist short term temptations in order to meet long term goals. We can call this delayed gratification.

- It is shown by the capacity to resist unwanted thoughts, feelings or impulse actions, overriding them with positive, sometimes altruistic intentions.

- Willpower is often characterized by using critical thinking and logical analysis rather than behaviour driven by ‘hot’ emotional reactions.

- It involves a conscious effort ‘by myself, for myself’ to both regulate actions and limit them.

- Willpower is limited, and when used up, affects other parts of your life. When exhausted at work, for example, there may be less willpower for social or family activities.

The last point is very important because it suggests that willpower is a limited resource. It can be used up elsewhere, for example managing stress. Researchers tested experimentally whether controlling emotions in difficult circumstances affected the ability of participants to continue with tasks, and found that it had a significantly negative effect. In any given period of time, if willpower is exhausted, we become more vulnerable to other challenges in life, resulting in increased depression, alcohol abuse and impulsive/reactive behaviour.

How can you replenish your store of willpower?

This question is currently the subject of lots of research studies. Many are associated with the idea of mindfulness – being sufficiently self-aware to recognize your current state and being able to relax with other people, to physically and emotionally recuperate, rebuilding your energy. Other studies support sleep, the importance of healthy eating and fructose sugars (like orange juice) having a similar effect. There is also strong evidence about the importance of optimism, psychological well-being and humour for maintaining willpower.

Willpower and well-being are also enhanced by your sense of purpose. It is important therefore that you set goals and targets for yourself, that they are right for you and that you can commit yourself to them.

Choose to pursue goals that are:

- Realistic and achieveable. (Unachievable goals become demotivators.)

- Personally meaningful and congruent with your needs and motives (which enhances commitment).

- Concerned with getting closer to others. (The significance of having a mindset which strongly features helping others is one of the driving forces that enables people to develop their emotional intelligence. Being concerned about others, then taking action to help, seems to be an important feature of psychological well-being.)

- Interesting and absorbing. (Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote an influential book in 1990 about the psychology of optimal experience. In it, he described how a state of ‘flow’– what athletes call ‘being in the zone’, being absorbed and enjoying total focus on something – produces satisfaction, happiness and psychological resilience, all of which are important components for sustaining willpower.)

Remember Anthony and Peter? They were two of the pen portraits we looked at in the introduction (pages 1–3).

Remember Anthony and Peter? They were two of the pen portraits we looked at in the introduction (pages 1–3).

Anthony spends money like there’s no tomorrow and deferred gratification is a concept he finds difficult. He is someone with many serious challenges in his personal life. As result, getting up to go to work each day and coming home to an empty house each night, maintaining the image he likes to project and succeeding in a competitive job pretty well exhausts his stock of willpower. He has become a heavy drinker, is subject to continuous low-level depression. He has no long-term goals to give him focus.

Peter’s willpower is also diminished on a daily basis. He struggles to cope with his relationship, having tried, unsuccessfully, to become what his wife wants and tried to ignore his own feelings and hopes. Now, keeping his frustration and anger under control is the biggest act of willpower he has ever faced. It isn’t limited to his home life. At work he is seen as volatile and someone to be cautious of and he has to make a supreme effort to maintain relationships with awkward customers. When he gets home, he says he just doesn’t want to know. His energy is low and he finds it difficult to make the effort to communicate in a way his wife wants. He has become vulnerable because he is now unable to confront the real causes of his unhappiness.

Being positive about goal-setting

As we have just seen, self-control is more than resisting a dangerous impulse. Real results often come from putting momentary needs on hold in order to pursue more important outcomes. The way we frame our goals and intentions can also make us feel in greater control – making them realistic, achievable and motivating. Being positive is a vital perspective for emotional intelligence. Try to structure your goals with the following questions in mind:

What do you want? (being positive): Goals need to be expressed in positive terms. This isn’t about Norman Peale’s ‘Power of Positive Thinking’, nor is it about ‘positive’ in the sense of being good. It refers to directing your behaviour towards something, rather than away from something you want to avoid – ‘What do I want?’ rather than ‘What do I not want, or wish to avoid’. Losing weight and stopping smoking are negative outcomes, as are reducing costs and avoiding losing customers. These are worthwhile, but communicate problems and negativity.

Try turning your goals into positive ones by asking ‘What behaviour do I want instead?’ or ‘What results do I need?’ For example, if you want to reduce conflict within your team, you can set the goal in terms of identifying opportunities for co-operation or establishing ways of taking into account perspectives from others’ roles.

How will you know you are succeeding? (evidence): It’s important to know you are on the right track towards your goals and that others who are involved know too. You need adequate feedback, and accurate information which is shared between all who need to know.

Is the goal defined specifically enough? (clarity and focus): Kipling’s ‘six honest serving men’, according to the poem, are ‘What and Why and When; and How and Where and Who’. More recent management-speak uses SMART to define clearly what needs to be achieved and so give both you and the others involved more control over what needs to be done. Goals need to be described in ways that are Specific, Measureable, Agreed, Realistic and Timed.

What resources can be devoted to this goal?: Resources tend to fall into five categories (some more relevant than others depending on what you want to achieve). Staying in control and reducing emotional pressure is achieved when your plans reflect realistically the resources available for getting things done. The categories of resources are:

- Objects: equipment, buildings, machinery/technology, books, manuals, etc.

- People: family, friends, colleagues, contacts, stakeholders.

- Role models: anyone you can talk to about their experience of doing similar tasks; someone who understands the problems involved.

- Skills and qualities: personal skills, aptitudes, experience, attitudes, capabilities and values.

- Money and time: Have you got enough, can you obtain more, what are the limitations?

What assumptions do you make? People often make assumptions about what they can achieve based on their interpretation of the situation and the way they predict that the people involved will respond. Emotional intelligence treats beliefs and perspectives as important presuppositions but not immutable laws like gravity or death. We may need to question our own ways of looking at things before we can take action to achieve our goals.

Emotional intelligence treats beliefs as important presuppositions but not facts. They may be an important causal factor for others’ (or your own) behaviour but we have a choice about what to believe. Sometimes, despite the obvious problems, we may need to question the mental models that are being applied before we can move towards acting on our goals.

Emotional intelligence treats beliefs as important presuppositions but not facts. They may be an important causal factor for others’ (or your own) behaviour but we have a choice about what to believe. Sometimes, despite the obvious problems, we may need to question the mental models that are being applied before we can move towards acting on our goals.

How are beliefs and perceptions connected to reality?

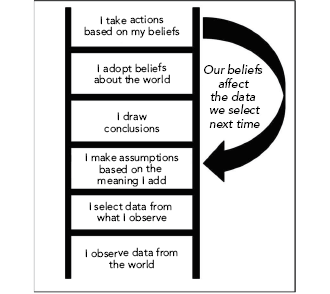

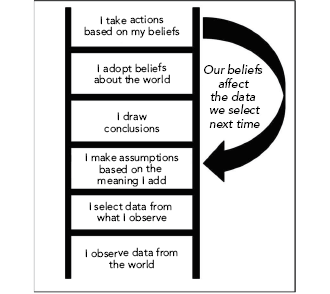

Beliefs are mental models from our experience and history, based on our perceptions. But beliefs also play an important role in the first place by shaping our understanding of what is real. The ‘Ladder of Inference’ shown below was first put forward by organizational psychologist Chris Argyris and used by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization.

The diagram illustrates the argument that we are selective about the way we experience the world, modifying our real experience by adding meanings, making assumptions and drawing conclusions which both shape and affirm our existing beliefs and future approach. But the beliefs we have adopted create filters, through which we will see and interpret our future experiences. These filters affect which information we will place value on the next time, giving us a picture that may be a long way from what actually happened.

Perhaps the most significant contribution that emotional intelligence can make is to allow our thinking processes to be informed and enriched by our emotions and beliefs – while preserving our ability to see what is happening accurately and without bias.

Our beliefs and assumptions act as filters for what we see and what we observe.

Our beliefs and assumptions act as filters for what we see and what we observe.

How are your goals and beliefs linked?

How are your goals and beliefs linked?

- What beliefs do you hold about the following:

- Other people in general?

- Your work colleagues?

- Your boss?

- Improving your career?

- Family and children?

- Having a successful life?

- What are your short-term and long-term goals? Where do you want to be in five years’ time?

- Which of the beliefs you identified affect your goals?

Assertiveness

For many years, assertiveness has been seen to be a tool of successful people management and leadership. Emotionally intelligent leaders are often seen to be ‘comfortable in their own skins’ – seeing themselves in an honest but clear light and with good self-esteem. They tend to be straightforward and self-aware – when they are angry they control it but deal with things in a straightforward way, letting others know how they feel. Staying composed when being pressurized, they are able to express themselves with optimism and avoid making themselves the centre when the spotlight should be on the action they want.

Assertiveness is about getting things done and engaging others to help but at the same time acknowledging that others’ needs and goals are important. It is about expressing feelings, thoughts, and beliefs in a non-destructive manner which is neither passive nor aggressive. The aim of assertiveness is ‘win–win’. It means:

- Expressing views and opinions, wants and needs openly and without fear

- Active listening, to evaluate what response you are getting

- Drawing out the interests and goals of the other person

- Trying to identify common ground whilst being clear about what’s important

- Using incentives, problem-solving and encouragement to agree future action.

These behaviours straddle a middle ground between giving in, which involves passively bottling up your emotions and needs, and competing strongly, fighting for your own interests and supremacy. Being assertive rather than dominant makes people more receptive to fitting in with you.

Assertiveness can be:

Assertiveness can be:

- Saying what you think

- Making requests and asking for help

- Negotiating solutions acceptable to everyone

- Refusing requests

- Refusing to be patronized or put down

- Making complaints

- Clarifying expectations

- Expressing your optimism in the face of negativity

- Showing appreciation, affection, hurt feelings, justifiable annoyance

- Overcoming hesitation about ‘putting things on the table’