HIGH NET GROWTH

I did stand-up comedy for eighteen years. Ten of those years were spent learning, four years were spent refining, and four were spent in wild success.

—Steve Martin, Born Standing Up

I WAS SITTING BEHIND A CARD TABLE in the sticky Texas heat at the South by Southwest Conference in 2011, signing copies of Life After College at a small launch party. The books were not even in stores yet—they were truly “hot off the press.” The first person in line walked up to the table and, as I started signing, asked, “So . . . what’s next?”

I stuttered and stammered through an awkward reply. Even though he had the best intentions, I could not help but feel a bit deflated. It was so strange. Here was this massive project, this life goal embodied in a bound stack of paper, sitting in my hands after three years of staring down my gremlins to write it, and people were already asking what’s next.

The truth was, I had no idea. I had just started three months of unpaid leave from Google, and as regularly as brushing my teeth, I agonized over my own next career move as the clock on my sabbatical ticked down. Every day I struggled with what the right decision would be: return to Mountain View after my book tour, ask to work part time from New York City, or leave the company altogether? Should I make the safe, secure choice? Or should I take the risk of leaving and do the thing that terrified and excited me most by taking my own business full time?

Though I loved my time at Google—it was the best five-year MBA I could ask for—ultimately I felt I could make the biggest contribution if I pursued a new direction. I ran the numbers: I could support up to 35,000 Googlers at the time through internal career development programs, or I could leave and try to expand my reach and global impact to a far greater number, following my personal mission to be as helpful as possible to as many people as possible.

Some people measure their lives in terms of money, orienting their careers around acquiring wealth and material markers of success. Those who have accumulated financial wealth are considered high net worth individuals. But for the vast majority of people I encounter, money is not the number one driver of purpose and fulfillment. It is only a partial means to that end. A study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton confirms this: once people surpass $75,000 in annual net income ($82,000 in today’s dollars), they experience no statistically significant bump in their day-to-day emotional well-being.

For many, money is nice to have, but not at the expense of soul-crushing work, if they have the economic flexibility to choose otherwise. The people I am talking about, and the ones for whom this book will resonate most, are those who are unwilling to settle for a career of phoning it in. They are willing to pay dues, but are not prepared to sit stalled for long, unable to see the value or impact of their work.

These individuals optimize for high net growth and impact, not just high net worth. I call them impacters for short. Impacters love learning, taking action, tackling new projects, and solving problems. They are generous and cooperative, and imbued with a strong desire to make a difference.

Impacters aim first and foremost for a sense of momentum and expansion. They ask, “Am I learning?” When their inward desire for growth is being met, they turn their attention outward, seeking to make a positive impact on their families, companies, communities, and global societies. Often these happen in tandem; by seeking problems they can fix and tackling them, impacters meet their needs for exploration and challenge, uncovering callings along the way.

Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck, author of Mindset: The Psychology of Success, discovered in her research that the most successful people are those with a growth mindset. These are people who believe that their basic qualities are things they can cultivate through their efforts, rather than believing their gifts (or lack of them) are fixed traits. The truth, Dweck says, is that brains and talent are just the starting point. “The passion for stretching yourself and sticking to it, even (or especially) when it’s not going well, is the hallmark of the growth mindset,” Dweck writes. “This is the mindset that allows people to thrive during some of the most challenging times in their lives.”

Maintaining a growth mindset is critical to navigating a pivot successfully. By seeing change as an opportunity, rather than a personal shortcoming or obstacle, you will be much more likely to find creative solutions based on what excites you, rather than subpar choices clouded by fear. Making career moves based solely on running from unhappiness and avoiding fear is like trying to fix a gaping wound with a Band-Aid; the solution does not stay in place for long. With a growth mindset, you will be open to new ideas, observant in your experimentation, deliberate in your implementation, and flexible in the face of change.

Fixed anything doesn’t work for impacters, who are allergic to stagnation and boredom. Author Tim Ferriss captured this sentiment in The 4-Hour Workweek, saying, “The opposite of love is indifference, and the opposite of happiness is . . . boredom.” It turns out that boredom itself can induce stress, causing the same physical discomfort as too much work: increased heart rate and cortisol levels, as well as muscle tension, stomachaches, and headaches.

For impacters, boredom is a symptom of fulfillment deficiency—of not maximizing for growth and impact—rather than a sign of inherent laziness. As University of Waterloo professor of neuroscience James Danckert wrote, “We tend to think of boredom as someone lazy, as a couch potato. It’s actually when someone is motivated to engage with their environment and all attempts to do so fail. It’s aggressively dissatisfying.”

In her 1997 study, Dr. Amy Wrzesniewski, associate professor of organizational behavior at Yale University’s School of Management, proposed that people see their work as a job, career, or calling. Those with a job orientation see work as a means to the end of paying the bills; those with a career orientation are more likely to emphasize success, status, and prestige; and those with a calling describe work as integral to their lives, a core part of their identity and a fulfilling reward in itself. Impacters fall clearly into the second category and aspire to the third, if they are not already there.

Impacters are not just asking What did I earn? but What did I learn? What did I create? What did I contribute? They measure their quality of life by how much they are learning, challenged, and contributing. If they are doing all three intelligently and intentionally, they work hard to ensure that the money will follow.

It is not that impacters are not interested in money—they are. They have no desire to live as starving artists. They know it is challenging, if not impossible, to focus on others if one’s own basic needs are not met first. But when faced with the prospect of a career plateau, they would make the horizontal move, leave the cushy corporate job, or bootstrap their own business to prioritize growth and impact. A person who aims for learning and contribution may rank intellectual capital over financial capital if pressed to choose, but often ends up wealthy in both.

Take Christian Golofaro and John Scaife, who traded coffee and cotton in the open outcry pits on Wall Street for five years. Tired of the daily pressures of their jobs and looking for meaning beyond buying and selling commodities, they pooled their money in 2014 to start an urban farming business in Red Hook, Brooklyn. They sought to help revolutionize food production by bringing fresh, local, pesticide-free produce to New York City year-round. They were more inspired as impacters in their new business, SpringUps, than they ever were in finance.

Though he spent thousands of hours in high school and college preparing for a career in medicine, Travis Hellstrom decided to join the Peace Corps after graduation instead. He gave up his full ride to medical school and moved to Mongolia, where he served in the Peace Corps for over three years, living on two hundred dollars a month. When Travis reflects on the decision, he says, “It took a lot of soul-searching and being okay with disappointing myself and others, but I left my life and found my calling.” After he returned, Travis pivoted again to nonprofit coaching and community management. Several years later, he parlayed that independent consulting work into a role as chair of the Mission-Driven Organizations graduate program at Marlboro University.

Impacters continue learning and contributing throughout their working lives, which often extend far past what is traditionally thought of as retirement age. When I asked Kyle Durand about his impending retirement from the military after twenty-seven years of service, his sentiments reflected those of many people I know who have no plans to retire in the traditional sense.

“I think retirement is an antiquated notion. The whole idea that you work for most of your adult life in order to eventually do the things you want is outmoded,” Kyle said. “My retirement from the military is simply closing the chapter on that part of my career, but it is not the end of my working days by any stretch. Now I can shift into building my businesses full time. That is my future, part of my legacy. That is how I want to make an impact with the people I care about.”

Christian, John, Travis, and Kyle pivoted in new directions that were more aligned with their values, interests, and goals, even though there was not a guarantee of success. As impacters, they saw these changes as opportunities for growth and recognized that their ability to learn and adapt would help them land on their feet no matter what. This helped them maintain a positive outlook throughout their pivots, knowing they would benefit from following their instincts and aspirations instead of societal expectations, no matter the outcome.

As I was writing this book, many of the people I initially interviewed returned six months or one year later and said things like, “Don’t bother putting my story in the book. I am pivoting again.”

This manifested in a variety of ways: they got poached by another company for an even better role; their company folded, got acquired, or got sold; they decided not to pursue a new skill or industry after all; they realized entrepreneurship was or was not for them; or they shifted their business into a more promising new direction.

Hearing these updates did not surprise me, nor did it mark their initial pivot as a failure. Instead, they are prime examples of what it means to be high net growth and impact individuals. I expect to hear that impacters are pivoting and adjusting dynamically at every turn.

For a directory of people featured in this book and what they are up to now, visit PivotMethod.com/people; for audio interviews and episodes from the Pivot Podcast, visit JennyBlake.me/podcast.

CAREER OPERATING MODES

An essential facet of the Pivot mindset is self-awareness. How are you currently showing up in your day-to-day work? Are you operating at your desired energy levels, creative output, and impact? I have observed four primary Career Operating Modes among pivoters: inactive, reactive, proactive, and innovative. The first two are impacter stressors, the latter two are sweet spots:

- Inactive: Does not seek changes; paralyzed by fear, uncertainty, and self-doubt; covers up career or life dissatisfaction with unhealthy habits, such as numbing out with excessive amounts of food, alcohol, TV, video games, and so on; feels and acts like a victim of circumstances.

- Reactive: Mimics others’ models for success without originality; follows instructions to the letter; waits for inspiration to strike; “phones it in” at work; feels unhappy, but does not inquire into why or what to do about it; lets fear overrule planning for the future and subsequent action steps.

- Proactive: Seeks new projects; actively learns new skills; is open to change; improves existing programs; makes connections with others; takes ownership even within existing leadership structures; has a giver mentality, willing and interested in helping others. May not be fully using innate talents, but is exploring what they are and how to amplify them.

- Innovative: In addition to proactive mode qualities, fully taps into unique strengths; focuses on purpose-driven work and making meaningful contributions; is energized by a strong vision for new projects with a clear plan for making them happen; does not just improve existing structures, but creates new solutions to benefit others.

Impacters thrive in situations where they are able to be proactive and, even more so, innovative in driving their career forward, implementing new ideas and creatively solving problems, stretching to the edges of what is possible for themselves and the companies they start or work for. When impacters find themselves in inactive or reactive operating mode, they look to pivot again toward a new, more engaging opportunity.

Although it is true that some people may work in inactive or reactive mode for their entire careers, this is not a life that impacters can stomach. The boredom, anxiety, and feeling of standing still becomes increasingly intolerable, often manifesting in physical symptoms such as headaches, getting sick more frequently, or worse.

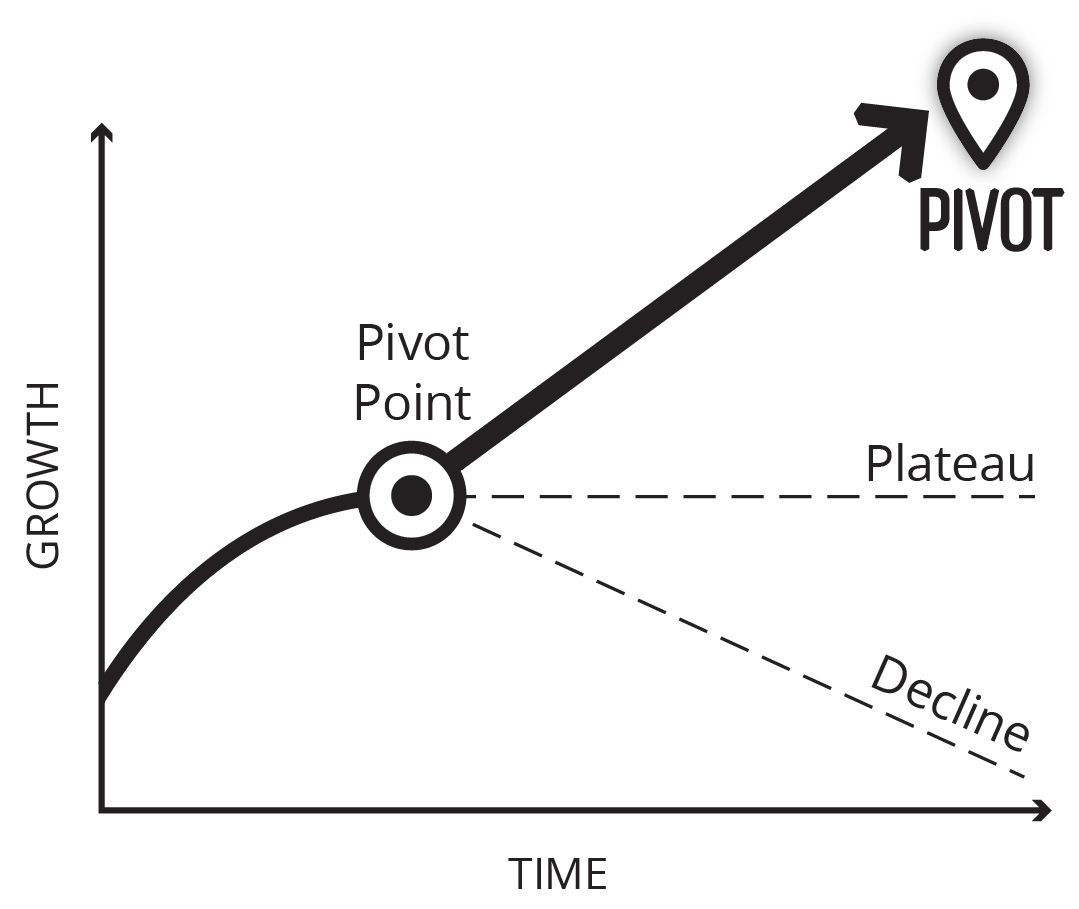

Plateau Versus Pivot

At these critical pivot points, impacters must recognize this tension and take action. Otherwise the unhappiness from staying still for too long compounds, making the career confusion feel insurmountable, and taking it from conundrum to crisis.

Though they may get restless more easily, impacters do have a distinct advantage: by seeing career boosts and setbacks as learning opportunities, all outcomes become fodder for growth. Nassim Nicholas Taleb captures this concept in the six-word title of his book Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder.

Antifragile organisms do not simply withstand change and survive it; they become better because of it. A glass is fragile. If you drop it, it breaks. A tree is resilient. In strong winds, it sways but stays standing, more or less remaining the same. Organisms that are antifragile actually benefit from shocks. Taleb invokes Hydra, the creature from Greek mythology: when one of Hydra’s many heads is cut off, two grow back in its place. The tough-times cliché is true: what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. According to Taleb, antifragile organisms “thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors,” and “love adventure, risk, and uncertainty.”

Love risk and uncertainty? Huh? Aren’t these things to be mitigated, if not entirely eliminated? Not if you want to be antifragile in a world that is ruled by them. Impacters find ways to thrive in uncertainty and disorder. Rather than merely reacting to randomness or becoming paralyzed by it, they look for opportunities to alchemize what is already working into what comes next.

TRUST YOUR RISK TOLERANCE

After much deliberation, I chose not to return to Google after my sabbatical. That is when I first realized that financial security and great benefits were important to me, but not the ultimate drivers of my career decisions.

I knew it would not be fair to Google or to my book to give both projects short shrift by taking on too much. I also knew that I could not sustain the pace of keeping side projects and a full-time job much longer. I was exhausted and on the express train back to burnout, where I had unfortunately been too many times in prior years. Moreover, I had a hunch that leaving to start my own business would spring me out of proactive mode and challenge me to become the innovative impacter I longed to be. So in July 2011, I became a free agent.

Fast-forward one year and once more I was struggling, racking my brain about what’s next . . . again. I would be turning thirty soon, and although I was proud of Life After College, I did not want to talk about it exclusively for the rest of my career. At the same time, in speeches and interviews, I had become known as “the girl who left Google.” Even during my time there, I often felt uncomfortable with how much of my identity and professional self-worth was tied up in the company’s shadow, and here I was again, facing the same issue from another perspective.

I was defined by leaving things, but wanted to look ahead to a more energizing mission. What did I stand for? What problems was I passionate about solving? How could I build a sustainable business that would help me make a meaningful impact on others’ lives?

For the next two years I wrestled with these questions, this time without a steady paycheck to fund the exploration. It was much more nerve-racking as my livelihood now depended on the answer.

My tireless brainstorming took me further from myself, not closer. I circled around big ideas, big bets, and big leaps. But really, I kept entertaining options out there. Although any one could have been a brilliant idea to pursue over the next six months, they were not going to help me pay my bills this month.

I felt like I was on a spinning teacup ride: I was dizzy, tired of circling vague ideas without a clear way forward, and nauseated about how to support myself. I am a grown adult, I thought. There is no excuse for this.

I understand now that I made the same mistake I see other pivoters making: underestimating what I was capable of, particularly in a sink-or-swim situation, by looking too far outside of myself for answers. I set my sights on next steps that were inaccessible given my starting point and timeline, and that ultimately prevented me from making real progress.

Barring massive events outside of our control, there is a sweet spot for when and how to pivot. You probably won’t know with 100 percent certainty when to make your next big career move, but you can get a lot smarter about how you reduce the risks and potential margin for error—error in the sense that you end up worse off than you are now.

Riskometer

We all have a different risk tolerance. What is risky for someone else may be a snoozefest for you. Take your risk temperature by identifying which of the four zones you currently fall into on the Riskometer diagram below. Keep these distinctions in mind as you proceed with your pivot. Pay attention to when you start playing it too safe (when you might find yourself slipping from the comfort zone into stagnation), when something feels edgy but exciting (stretch zone), or when a next step seems too overwhelming or extreme (panic zone).

Riskometer Reading

- Stagnation zone: Restless, antsy, trapped, anxious, or bored. May start manifesting as physical symptoms and health problems.

- Comfort zone: Feeling good about the status quo; daily life doesn’t demand much deep thinking about the direction of your career. Work is “fine.”

- Stretch zone: Challenged, excited, and motivated to get out of bed every day. Actively learning; work may be unpredictable, but you feel engaged.

- Panic zone: Anxiety is starting to dominate your thoughts; you are not able to think long term about the future because you are dealing with things that are “on fire” in your day-to-day life. Or, if contemplating next steps, you feel so paralyzed by fear that you end up doing nothing.

Career pivots can stretch us to our maximum capacity, and often even a bit further, but they do not have to be debilitating. Working through the four Pivot stages will help you avoid extremes on the risk spectrum: neither taking a blind leap, nor analyzing yourself into the ground by overcalculating every step. The ideal range for change for impacters is in the stretch zone: the place where you feel challenged, excited, and focused, with a healthy dose of adrenaline propelling you forward.

One way to visualize the amount of risk, reward, and work required for your pivot is to imagine plotting your move on a graph. With time on the x-axis, and growth on the y-axis, the degree, or incline, of your next move can be viewed as the amount of resources it consumes in time, money, energy, and effort. A pivot can be subtle, say a 20-degree turn, such as moving to a new team at work. Or a pivot can be sharper, say 70 degrees, such as switching industries or leaving your job to start a business.

Avoid pivots that are too sharp, too far past your stretch zone—what I call 180s. These are dramatic leaps of faith that have little to do with your current role or skill set, which means there are too many unknowns that you would be gambling on when you launch. However, even what sometimes looks like a 180 from the outside might actually be, in execution, a pivot comprising a series of smaller steps that paved the way for larger change.

If your mission makes your heart sing, but the idea of launching into it tomorrow gives you a serious case of anxiety—or agita, as Italians would say—build incrementally toward the final Launch stage by planting, scanning, and piloting.

TWO (MANY) STEPS AHEAD, ONE STEP BACK

Thinking too many steps ahead about how to pivot my career and business in those first years after my book was published sent me into my panic zone. I was choked by fear, which was magnified by not knowing how I would consistently cover the basic practicalities of my life. As they say in the financial world, I was about to “blow up.” If I blew up, it would be time to get another full-time job. There is nothing objectively wrong with that, but every cell of my body told me that it was not the answer for me, at least not yet.

All of a sudden it hit me: not once did I thoroughly examine my existing strengths. My book. My speaking engagements. The websites I had been building for seven years. The work activities I loved, who I knew, how I was already earning income. Any of these assets, if I was to dig deeper into them, could reveal a bounty of ten more related areas to pursue. I was so ready for the Next Big Thing that I shut myself off from looking at what was already working.

I realized I had dozens of apps already downloaded—skills, interests, and past experiences—all working in my favor, but that I had not been fully using. I had been so focused on what was not working, or what I did not yet have clarity on, that my transition turmoil lasted longer than necessary.

I felt tremendous relief when I stopped blaming myself for my career confusion and started taking smarter, more focused steps. Combing my past for clues to my future gave me a sense of buoyancy and relief: I can figure this out.

I started to celebrate the many things I was proud of and began experimenting with small extensions of the strengths and experiences I had been accumulating throughout my career. This boosted my confidence and empowered me to solve the puzzle sitting right in front of me, with new insight into the pieces already at my disposal.

In January of that key pivot year, I questioned how I would pay my rent. By December, my business was in its most profitable year ever. For the first time, I surpassed six figures, nearly tripling my income from the three years prior. I reconnected with an even stronger sense of focus and flow in my work. Not because a lightning bolt of luck struck me from above—though there were plenty of lucky encounters—but because I was determined to do things differently. I did not just happen upon my confidence again, I aggressively pursued it.

This is the book I wish I’d had during that time: A practical, tactical guide for the trenches of answering what’s next. A blueprint for getting unstuck, taking smart risks, and navigating uncertainty now and in the future. A book that would help me, and all of us, stop spinning and refocus all that brilliant energy back where it belongs—on making a positive difference for as many people as we are able to in this lifetime.