CHAPTER ONE

UNITED STATES

Mrs. Wilkes gave birth to a bouncing 10-pound baby at full term. When his circumcision would not stop bleeding, a hematologist was called and diagnosed the healthy-looking baby boy with hemophilia. He was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and infused with clotting factor. After a day of observation the baby was discharged.

Despite having health insurance, Mrs. Wilkes was billed $50,000 for the one night in the NICU—not including the hematologist who came and generously infused the clotting factor at no charge for both her time and the drug.

Ironically, Mrs. Wilkes made sure both her OB-GYN and the hospital were in network. But to her surprise, the hospital had subcontracted out the NICU to a 3rd party that refused to sign a contract with the insurer and, thus, was out of network—and able to charge whatever it wanted directly to the patient.

A dedicated and generous hematologist. Quick access to clotting factor. A system of in-network and out-of-network coverage that is impossible to navigate. Hidden and outrageously high prices for hospital care. Exorbitant patient out-of-pocket costs. In a few days, Mrs. Wilkes experienced many—though not all—of the evils of American health care… and this is with “good insurance.”

HISTORY

In 19th-century America, hospitals and physicians were not highly regarded.

Benjamin Rush, the father of psychiatry and signer of the Declaration of Independence, called hospitals the “sinks of human life.” Physicians were called snake oil salesmen. Change ensued at the end of the 19th century when scientific advances began making medical care safe and effective. Ether and subsequent anesthetics, initially demonstrated in 1846, allowed for painless, longer, and more careful surgeries. Germ theory, bacterial staining, and aseptic techniques reduced hospital-acquired infections, making surgery, recovery, and hospital stays safer. X-rays allowed for more accurate diagnoses. Consequently, middle-class Americans stopped fearing hospitals and began using them in larger numbers in the early 20th century.

In 1910, the Flexner Report on medical education led to the closure of many proprietary medical schools, replaced by university-affiliated medical schools modeled on those at Johns Hopkins, Case Western Reserve, and the University of Michigan. Instructors were no longer community practitioners earning side money but now full-time academic professors. The Report also ushered in a new curriculum composed of 2 years of preclinical scientific training and 2 years of clinical rotations in hospital wards. These changes drastically improved physicians’ quality and social standing, though the changes decreased the number of students from lower-income and rural communities.

Employers made the earliest attempts to provide health care or insurance in America. Many of these early plans consisted of employers hiring company doctors to care for rural workers, such as lumberjacks, who could not otherwise access medical services. In some cities unions created sickness funds to provide health benefits for their members. Physicians in rural locations also experimented with prepaid group practices.

But none of these efforts led to widespread health insurance coverage. This changed in 1929 in Dallas, Texas. Because of the Great Depression, hospital occupancy rates declined. To increase bed occupancy, Baylor University Hospital made a deal with Dallas schoolteachers. Baylor offered up to 21 days of hospital care per year for an annual premium of $6 per teacher. This arrangement succeeded and spread to other locales. It also evolved. Contracts were not with just one hospital but rather gave potential patients free choice among any hospital in a city. This nascent health insurance arrangement was further catalyzed because states permitted such plans to be tax-exempt charitable organizations, allowing them to circumvent many of the traditional insurance regulations, particularly the need to have substantial financial reserves. These hospital-focused plans adopted the Blue Cross symbol.

For a long time physicians were hostile to health insurance for physician services, worrying that insurance companies would threaten their clinical autonomy. Simultaneously, they worried that Blue Cross plans might begin to include hospital-based physicians in their insurance, taking business away from those in private practice. Ultimately, resistance to health insurance for physician services eroded because of the need to preempt Blue Cross plans and the persistent financial stress of the Great Depression. In 1939, the California Medical Association created an insurance product covering physician office visits, house calls, and physicians’ in-hospital services. Physicians controlled the insurance company, and it enshrined a patient’s right to choose their physician. The patient was to pay the physician and get reimbursed by the insurance company without any financial intermediary. This physician-focused model spread, and it often called upon state Blue Cross plans for management assistance and expertise. These physician-focused insurance companies became known as Blue Shield. Eventually the Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans merged. They were state-based because health insurance was regulated in the United States at the state level. They embodied key values: they were not for profit and sold community-rated policies that charged all people the same premium (regardless of health status) to cover as many people as possible at affordable rates.

In 1943, the first bill to create a national social insurance model for health coverage was introduced to Congress. After his unexpected victory in 1948, President Harry S. Truman also pushed for enacting government-provided universal health insurance. Primarily because of AMA opposition and worries about socialism at the start of the Cold War, the House and Senate did not vote on his proposal.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the US government enacted policies that accelerated the spread of employer-focused health insurance. First, in 1943 the US government enacted wage and price controls but exempted health insurance, allowing employers to provide coverage valued up to 5% of workers’ wages without violating the wage controls. Then in 1954, to encourage the further dissemination of employer-sponsored insurance, Congress enacted the tax exclusion, excluding an employer’s contribution toward health insurance premiums from an employee’s income and payroll taxes. This made a nontaxed dollar in health insurance more valuable than a taxed dollar in cash wages.

In 2019, this tax exemption amounted to nearly $300 billion per year and remains the largest single tax exemption in the United States. This spurred employers to cover more workers with richer health insurance offerings. Also, Congress passed the Hill-Burton Act in 1946, which provided federal funds to community hospitals for constructing and expanding facilities. It is estimated that through the 1970s the federal government paid one-third the cost of the country’s hospital construction and expansion.

Something became obvious in the 1950s, though: an employer-based system excluded retired, self-employed, and unemployed Americans from health insurance. In 1957, the first bill to provide coverage to seniors—Medicare—was introduced. But it took until 1964 and Lyndon Johnson’s landslide election victory for Medicare, government payment of care for the elderly, and Medicaid, government payment for some of the poor, to finally be enacted. The federal government’s generous payments to hospitals under Medicare further facilitated hospital expansion.

There were additional efforts to improve the US health insurance system—most notably in the early 1970s under President Nixon and in the early 1990s under President Clinton. Neither succeeded.

However, during these decades the health care system became increasingly costly and complex, with the addition of many new technologies and services, ranging from MRI scanners, new drugs, and laparoscopic surgical procedures to hospice, home care, and skilled nursing facilities. After adjusting for inflation, the annual cost of health care increased from $1,832 per capita in 1970 to $11,172 per capita in 2018.

Finally, in March 2010, President Obama and the congressional Democrats passed the Affordable Care Act (ACA), achieving what had eluded politicians for decades: a structure for universal coverage. Rather than enacting a social insurance model, the ACA expanded Medicaid to cover lower-income individuals and established insurance exchanges with an individual and employer mandate as well as income-linked subsidies for Americans earning up to $100,000. It also instituted policies to change payment structures and to achieve significant cost savings. This basic structure has remained in place despite the repeal of the individual mandate under President Trump.

COVERAGE

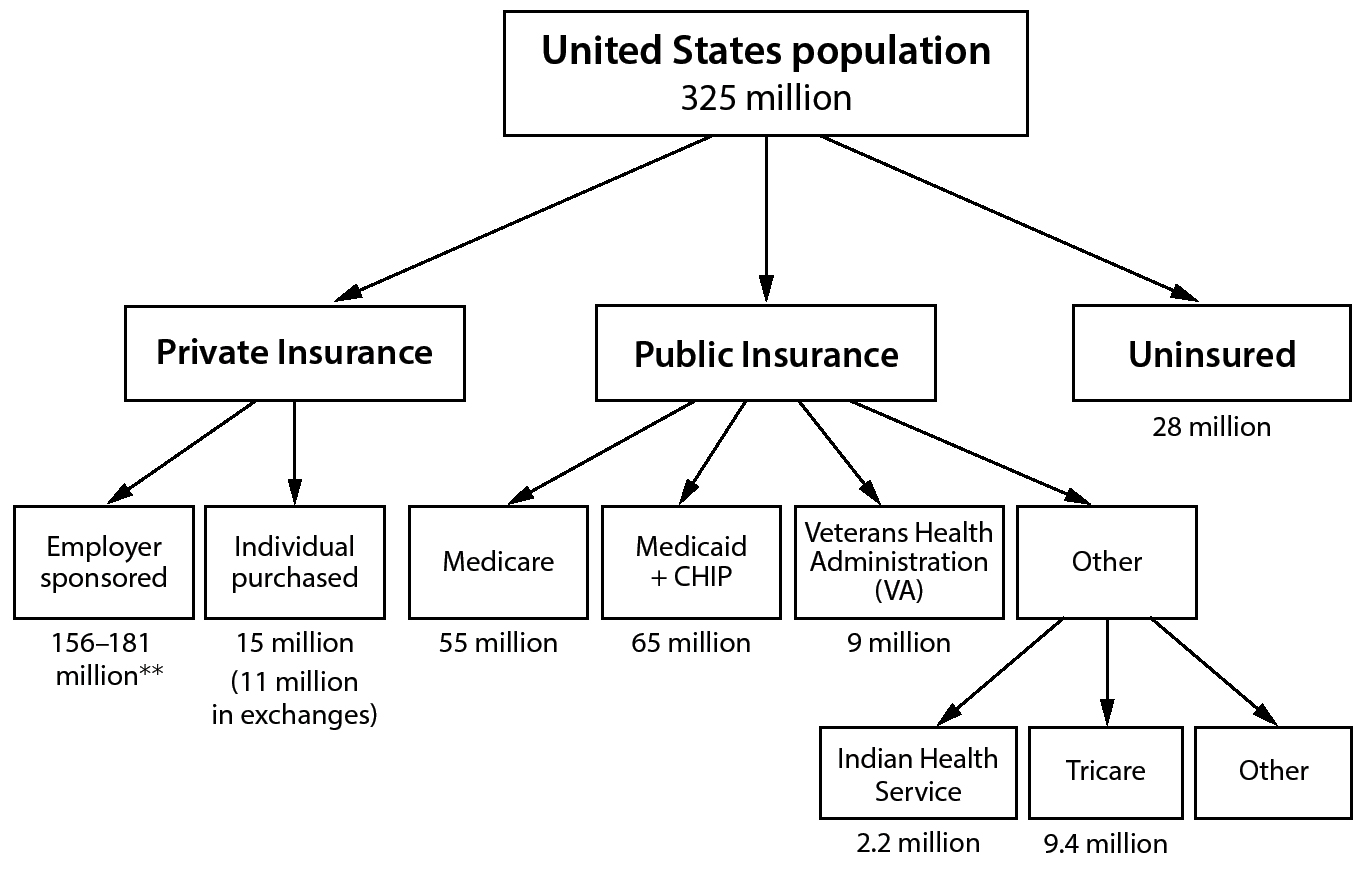

The American health care system is a patchwork of different insurance arrangements that is very confusing to navigate. The system has 4 main components and myriad smaller programs to provide health insurance to 290 million citizens, leaving approximately 28 to 30 million Americans without coverage.

The largest part of the system is employer-sponsored insurance. Employers either buy insurance for their employees and their families or are self-insured and have an insurance company, such as UnitedHealth or a state Blue Cross Blue Shield plan, paying claims and administering the plan. In 2017, employer-sponsored insurance covered about half of all Americans.

Second, Medicare covers all Americans aged 65 and older as well as permanently disabled Americans under 65. Medicare is composed of 4 programs covering different overlapping groups of people.

The original—what is called traditional Medicare—is Part A (hospital care) and Part B (physician and other ambulatory care services). The federal government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) administers it. Elderly Americans and those who are disabled and have contributed taxes to Medicare (or are a relative of someone who has) get Part A, but people need to sign up and pay a premium to receive Part B benefits.

Enacted in 1997, Part C—or Medicare Advantage—allows Medicare beneficiaries to select a private insurer or a health care plan associated with a delivery system for health insurance rather than traditional Medicare (Parts A and B). In 2003, Part D, Medicare’s drug benefit program, was passed. Private pharmacy insurance plans administer it. Medicare beneficiaries must pay a modest premium if they want the drug coverage. In 2017, Medicare covered about 18% of the population—58 million Americans, composed of about 49 million elderly and nearly 9 million disabled. About 20 million (34%) have Part C, and 43 million (76%) have Part D.

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage* (United States)

*Some individuals have more than one type of insurance. For instance, some veterans have VA health care and Medicare, and some elderly are “dual eligible” being poor and eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid.

**Data varies depending upon method of study.

Third, Medicaid provides coverage to lower-income Americans as well as the blind and disabled. The original Medicaid program was limited to the “deserving poor”—specifically, poor children, pregnant women, poor elderly, and the disabled. Each state administers traditional Medicaid, and they determine the qualifying level of income for coverage; sometimes it is as low as 25% of the poverty line for able-bodied adults.

Traditional Medicaid exists in the 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid. However, for states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, eligibility changed. It is no longer limited to the deserving poor with state-determined income thresholds. Instead, all people with incomes under 138% of the federal poverty line ($16,643 for an individual and $33,948 for a family of 4 in 2017) can receive Medicaid.