CHAPTER TWO

CANADA

To many conservatives in the United States, the Canadian health care system—also called Medicare—represents the perils of “socialized medicine,” rife with prolonged wait times and disgruntled physicians. Conversely, to many liberal Americans, it is the standard for sensible single-payer health care reform.

Paradoxically, there is no one Canadian health care system. Although united by 5 common principles, there are in reality 13 separate provincial and territorial Medicare programs that incorporate a diverse array of unique programs and financing mechanisms to provide care to their residents. As explained by Dr. John Lavis, “There are times Canadian provinces’ [health care systems] resemble another country far more than a neighboring province.”

Canadian Medicare constitutes a true single-payer system with an almost exclusively private delivery system. It also offers patients free choice of physician and no referral necessary for specialist care. There also are absolutely no deductibles or co-pays for CT or MRI scans, a physician visit, or any other service deemed “medically essential.” Yet there are serious problems, the most conspicuous of which is the absence of universal drug coverage in Canada. While the majority of Canadians have some kind of coverage for outpatient drugs through a hodge-podge of plans funded by provinces and employers, many Canadians, especially low-income citizens, totally lack drug coverage or have very inadequate coverage. As one Canadian physician complained, “I have patients who take their pills every other day, or who take them for a few weeks and then have to wait until the check comes in to fill [their prescriptions] again.”

Although the vast majority of Canadians support expanding Medicare to include drugs, the total cost and lobbying by the pharmaceutical industry has prevented legislation from passing. All the while many Canadians face a dilemma that is eerily similar to that found in the United States: patients failing to fill their prescriptions, taking smaller doses than their physicians ordered, or foraging for food and cutting back on heat and other necessities of life to pay for pills.

HISTORY

The origins of Canada’s health system lie in the rural prairies of Saskatchewan and Alberta, away from the bright city lights of Toronto, Montreal, or Vancouver. In these sparsely populated provinces citizens were spread thin, and doctors were a rare sight. In 1916, the provincial government of Saskatchewan passed the Rural Municipality Act to secure reliable medical care for remote populations. This act permitted local communities to hire physicians on contract. Given the region’s small population, this was one of the only ways to attract physicians with adequate compensation. This was highly atypical: the majority of basic health systems pay physicians a fee-for-service on the individual level rather than as a prepayment or guaranteed salary on a community level. The provincial governments also established multiple community hospitals. By 1930, Saskatchewan had 30 such rural hospitals. To finance these hospitals, the province charged residents a capitated rate of $1.21 USD ($1.60 CA) per year. In 1947, the Saskatchewan government passed the Hospitalization Act, which provided universal hospital coverage for all citizens, and over the next 2 years the federal government subsidized this program. Beginning in 1950, Alberta and British Columbia adopted similar models for hospital care.

After seeing the successes of these early programs, the federal government passed the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services (HIDS) Act in 1957. It offered matching funds to any provincial health plan that provided citizens with coverage for hospital care and diagnostic procedures. Over the next several years, provinces across Canada adopted their own health plans. By 1962, all provinces had instituted coverage for hospital services.

In 1962, Saskatchewan again pushed the envelope by including coverage for physician services in its insurance plan. The Canadian debate was similar to that in other countries: physicians did not want to hand over billing control and potentially lose professional autonomy, while the government sought more uniform coverage and better negotiating power.

A prolonged physician strike intended to repeal Medicare finally ended the impasse by turning public opinion against physicians. As with hospital coverage, over the next several years other provinces adopted their own plans covering physician services. Then, in 1966, through the passage of the Medical Care Act (MCA), the federal government again offered matching funds to any province offering a program that covered physician services. By 1972, all provinces also covered physician services.

Two decades later, in 1984, these 2 separate bills—the HIDS Act, covering hospital care, and the MCA, covering physician services—were unified through the passage of the Canada Health Act (CHA). This bill provided universal health care coverage for all medically necessary procedures and codified the 5 guiding principles of the Canadian health system: (1) universality, (2) accessibility, (3) public administration, (4) comprehensiveness, and (5) portability.

The universality and accessibility provisions guaranteed universal health coverage to all citizens without any cost sharing at the point of service for all services deemed medically necessary. The public administration provision locked provincial governments in as the insurance providers and stymied the rise of a 2-tiered insurance market by prohibiting private insurers from covering any services covered under Medicare. All plans were required to be comprehensive—to cover all medically necessary services—and to be portable between provinces. Notably, at the time, pharmaceutical spending was only a fraction of what it is today, so it was not covered.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the CHA, however, is how much it omits. Beyond outlining the 5 guiding principles to which provinces must adhere in order to receive federal funding, the CHA leaves everything else to the provinces and territories. This has led to a highly decentralized system—there truly is no single Canadian health care system; rather, there are 13 distinct systems united by common values. But how they realize these values differs sharply.

Since the passage of the CHA, the Canadian system has been remarkably stable compared to other nations. On the federal level especially, the CHA’s tenets continue to define the Canadian health care system’s organizing principles. On the provincial level, a great deal of experimentation, gradual expansion of health benefits, and a gradual—albeit growing—trend toward centralization have characterized the last few decades.

COVERAGE

Canada is a country of 37 million people. It has achieved truly universal health coverage through a 2-layered system: (1) mandatory basic health insurance provided by a diverse system of provincially administered public insurance programs and (2) a network of voluntary supplemental health insurance provided by private companies.

There are also a handful of federally administered programs that care for special populations, including the First Nations and members of the Canadian Armed Forces.

Coverage Model

All Canadian citizens enroll in one of the 13 provincial or territorial statutory health insurance plans, collectively referred to as Medicare. In accordance with the CHA of 1984, these plans are required to provide all “medically necessary services.” This includes all medically necessary hospital care, physician services, diagnostic tests, and inpatient pharmaceuticals. It is ultimately up to the province or territory to define the package, as there is no required list of procedures and interventions that must be covered. All services deemed medically necessary by provinces are both universal and completely free at the point of care. There are no co-payments, no coinsurance, and no balance billing.

What is considered to be medically necessary, however, is quite sparse.

Dental care, vision care, long-term care, ambulance services, and even outpatient pharmaceuticals are not uniformly covered by every province. In fact, Canada is the only developed country with a universal health plan that does not cover outpatient pharmaceuticals, though it is not for lack of trying. In the early 1960s, when provinces were expanding from only hospital coverage to physician services, pharmaceutical coverage seemed a natural next step. Including prescription drugs in health plans had significant support, such as a strong recommendation from a national committee known as the 1964 Hall Commission. But the federal government was ultimately scared off by the potential cost and restricted its offer of matching funds to only include physician services.

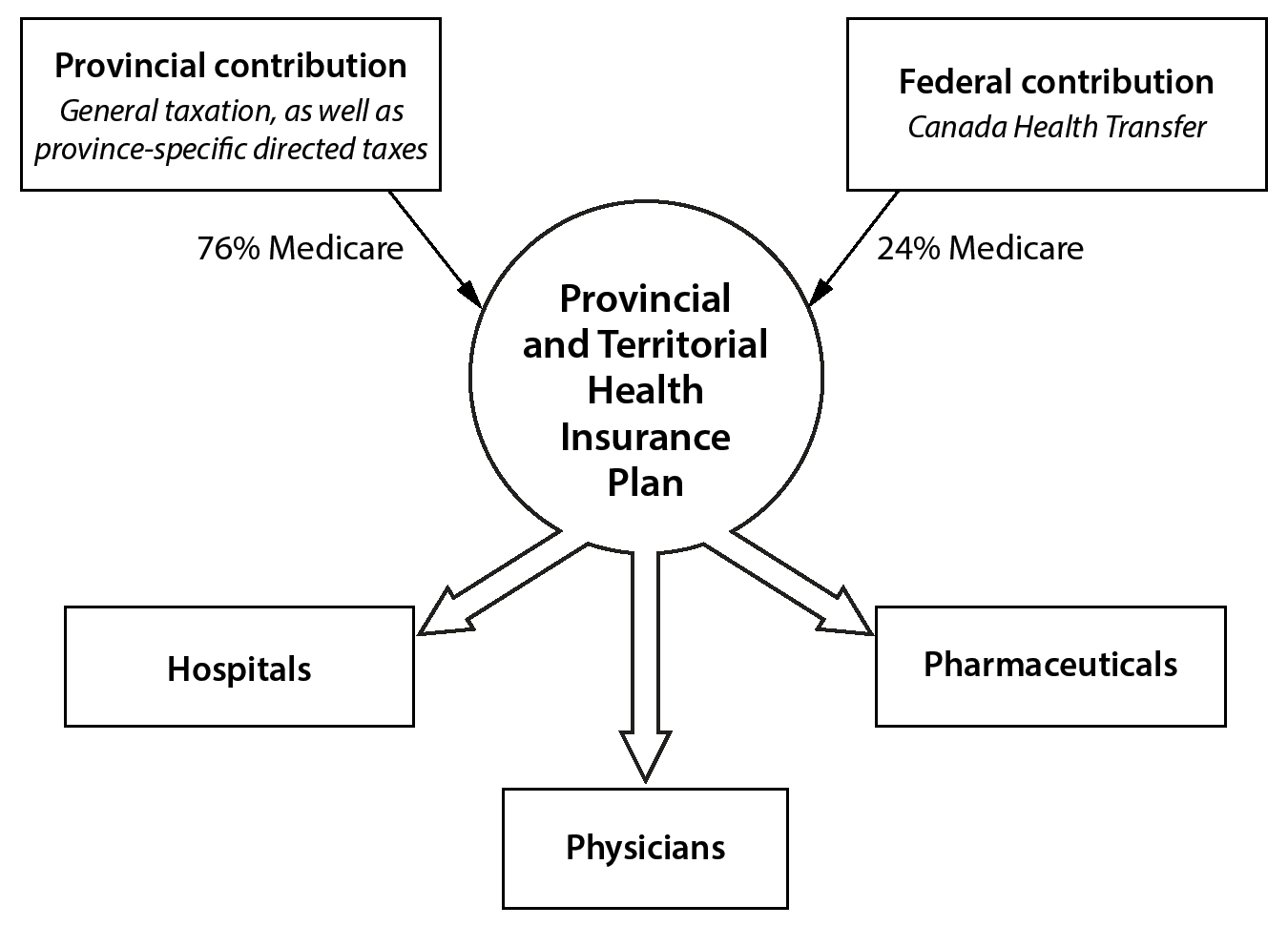

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (Canada)

At the time, pharmaceutical spending was a fraction of what it is today. It also was not seen as essential. In the mid-1990s, the debate was revived when the National Forum on Health, an advisory body formed by the prime minister, made a strong recommendation for a national prescription drug plan. Ultimately an economic slowdown stifled it. As a result, the Canadian health system now relies on a patchwork of provincial plans, population-specific federal plans, private supplemental insurance plans, and out-of-pocket payments to cover outpatient pharmaceuticals and other services not deemed medically necessary.

Each province also has its own additional health benefit programs; these are typically needs based, target select populations, and have some element of cost sharing. For example, in Ontario outpatient pharmaceuticals are covered for all persons aged 65 and older through the Ontario Health Insurance Program’s (OHIP) Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB). The disabled population enrolled in Ontario’s Disability Support Program and the poor population enrolled in Ontario Works are also eligible for this benefit. All persons aged 25 and younger without private coverage are insured through OHIP+. Those with significant drug expenditures can apply for needs-based coverage through the Trillium Drug Program (TDP). However, there is little uniformity between these programs. OHIP+ for persons under 25 has no deductible or coinsurance, ODB for the disabled, poor, and elderly has no deductible but does have a $1.52 USD ($2.00 CA) co-payment per prescription for low-income households or a $75.80 USD ($100 CA) deductible with a $4.63 USD ($6.11 CA) co-payment for high-income households, while TDP for the medically burdened with high drug costs has a deductible equal to around 3% of household income without coinsurance.

Quebec also has a publicly administered plan, the Public Drug Insurance Plan (PDIP), but only offers it to persons aged 65 and older and those younger than 65 who lack access to a private pharmaceutical plan. Quebec couples this with an individual mandate requiring all persons younger than 65 who can purchase a private plan through their employer, professional association, or spouse to do so. Quebec’s PDIP has monthly premiums ranging from $0 to $480.10 USD ($0 to $636 CA), depending on income, a $16.45 USD ($21.75 CA) deductible, 0% to 37% coinsurance, depending on income, and monthly and annual caps of $70.38 USD ($93.08 CA) or $844.62 USD ($1,117 CA).

The federal government also offers coverage for additional fringe benefits to special populations, including the Inuit and First Nations. These benefits vary, but they generally include outpatient prescription drugs and some dental and vision coverage.

AS A RESULT of the patchwork pharmaceutical, dental, and vision coverage, over two-thirds of Canadians purchase private supplemental health insurance plans. These plans are almost exclusively provided through employers (93%). While there are some individual plans, they are not subsidized either directly or through the tax system. Historically these plans have been prohibited from competing with Medicare by offering duplicative benefits. But in a landmark decision, Chaoulli v. Quebec in 2005, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled that Quebec’s statute prohibiting private insurers from covering Medicare-covered services was unconstitutional.

Since 2005, little movement has occurred in the market, and these plans continue to be largely complementary. These plans, moreover, are not used to increase access to desired physicians. They are typically used to decrease wait times for diagnostic procedures and elective surgeries. Several provinces and territories have enacted additional legislation to discourage these plans by, for example, prohibiting physicians from accepting both supplemental insurance and Medicare.

Households bear the remainder of costs. These out-of-pocket costs represent 14% of total spending, or $669 USD ($882 CA) per person, mostly for prescription drugs (21%), long-term care (22%), dental care (16%), vision care (9%), and over-the-counter medications (10%). While balance billing continues to be almost nonexistent, doctors in some provinces are allowed to charge annual fees for non-Medicare services, such as doctors’ notes and over-the-phone refills.

FINANCING

Canada spends $193 billion USD ($254 billion CA) per year on health care, equal to 11.3% of its GDP, or about $4,800 USD ($6,400 CA) per person. This is relatively high compared to other developed countries, but it is far below the United States and Switzerland. Staying true to the CHA, Canada maintains a federalist funding scheme for Medicare: the national government provides an annual payment to provinces in exchange for their adherence to the 5 core principles. The supplemental market is almost exclusively financed through private, employer-sponsored health companies.

Provincial and Territorial Health Insurance Plans: Canadian Medicare

Medicare finances around 70% of total health care spending and is funded jointly by individual provinces and the federal government through a highly progressive system of taxation.

Provinces pay for roughly three-fourths of Medicare costs, covering all essential health benefits and any additional special benefit programs. The vast majority of provincial funds comes from general taxation, although some provinces have developed a variety of special funding mechanisms. For instance, in Quebec there are surcharges on each household’s regular income tax, and any individual who registers for their public pharmaceutical coverage is subject to an additional monthly premium. In Ontario, there is a dedicated Ontario Health Premium that can be as much as $682 USD ($900 CA) per year for households making more than $15,159 USD ($20,000 CA) annually. In British Columbia, a fixed monthly premium supplements general tax funding—although it’s waived for low-income households.

Figure 2. Financing Health Care: Medicare (Canada)

The federal government pays for roughly one-quarter of Medicare costs through a fixed annual block grant known as the Canada Health Transfer (CHT). Originally the federal government paid half of the costs each province incurred while providing hospital and physician services. This was an annual shared-cost transfer. In 1977, however, the provinces and federal government agreed to change this arrangement. The provinces took the amount they were paying (half of all costs) and converted half of it into a permanent tax transfer and the other half into an annual cash transfer. The permanent tax transfer took taxable revenue from the federal domain and gave it to provinces, while the annual cash transfer was indexed to economic growth. The federal government favored this approach because its annual contribution was now fixed and not tied to fluctuating rates of health care expenditure, while provinces favored this because the tax transfer was projected to bring in more revenue than the previous shared-cost transfer, especially for the economically advantaged—and politically powerful—provinces of Ontario and Quebec.

Since that decision was made, this arrangement has been quite favorable to the provinces. Whereas the annual cash allocation—the CHT—represents only 24% of Medicare expenses, the net value of that 24% cash transfer plus the additional tax transfer far exceeds 50% of Medicare costs. Still, as Dr. Gregory Marchildon, chair of health policy at the University of Toronto, explains, “provinces have conveniently forgotten the tax transfer, and because it’s such a complicated argument, it’s hard for the public to appreciate.”

Although the Canada Health Transfer is similar in many ways to the United States’ Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage (FMAP) annual grants to states to finance Medicaid, there are several key differences. First, the CHT is calculated strictly based on a per capita basis, without adjustments for different levels of economic prosperity at the provincial level. Second, the CHT rate increases at a standard rate each year set by law regardless of whether health costs increase more or less than the standard. And finally, the CHT amount is not used as a stimulus during economic downturns as the FMAP is routinely used in the United States.

Supplemental Insurance

The supplemental insurance market pays $21 billion USD ($28 billion CA) per year, or around 12% of total health spending. Premiums collected by private insurance companies fund it. As of 2016, there were 133 private health insurance companies, 80% of which were for profit. The vast majority of these plans (95%) are offered through employers or unions, and premiums are tax exempt in all provinces except Quebec. Companies tend to cover the premium when offered as a benefit.

The private, supplemental insurance market is loosely regulated. As Dr. Marchildon says,

Provincial governments are responsible for regulating the market, but there’s not a lot of control in the traditional sense because these services—outpatient pharmaceuticals, dental, and vision—are not considered life or death. So, it’s up to the employers dealing with their unions to decide exactly what and how deep and broad coverage should be. It’s like the US market, except the stakes are not too high.

This has led to a largely self-regulated market that does, technically, allow for exclusions based on preexisting conditions, age, gender, and geography, although these practices are rare and, culturally speaking, nonstarters. Maximum payout limits are also not uncommon among private insurers. For instance, some private plans limit the total amount of drug coverage an employer may purchase for its employees to around $15,000 USD per beneficiary.

Long-Term Care

Long-term care in Canada accounts for just under 10% of total health care spending, or $15 USD billion ($20 billion CA) annually. Like pharmaceuticals, long-term care coverage is provided through a patchwork of provincial plans, special federal programs, and out-of-pocket costs. Unlike pharmaceuticals, though, the private insurance market is underdeveloped and pushes a significant share of costs to patients as out-of-pocket payments.

Long-term medical services, including devices and nursing services, are largely covered through provincial health plans. Not surprisingly, these plans’ generosity varies between provinces. Some are means tested; others are not. Additionally, what is covered varies by province. In Ontario all physician services are covered through the provincial Medicare program, known as OHIP, while nursing and support services are covered through the Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) without cost sharing to all eligible citizens.

Long-term housing services, such as board for nursing homes or assisted-living facilities, are generally left for patients to pay out of pocket, although safety-net programs exist in many provinces. However, these safety nets’ quality is also highly variable, and out-of-pocket caps in some provinces exceed $22,740 USD ($30,000 CA) per year. In Ontario, patients are charged a standard housing fee of around $1,345 USD ($1,775 CA) per month for a shared room, $1,630 USD ($2,150 CA) for a semiprivate room, or $1,933 USD ($2,550 CA) for a private room. Subsidies are available for those unable to afford these rates, and daily rates of around $29 USD ($38 CA) are possible for short stays. In Quebec, rates are set significantly lower: $866 USD ($1,142 CA) per month for a shared room, $1,164 USD ($1,536 CA) for a semiprivate room, and $1,392 USD ($1,837 CA) for a private room.

Payment for long-term care remains a contentious issue in Canada. Prominent think tanks and policymakers have made several calls to include coverage under Medicare. Recently one provincial party promised to incorporate long-term coverage in Medicare, but this was ultimately not implemented due to resistance around funding. Although the private market could potentially fill this void, a lack of regulations prohibiting exclusions based on preexisting conditions hinders this option.

Public Health

Public health represents 1% to 3% of total health care spending and is funded through a variety of federal and provincial sources. Preventive services such as vaccines and cancer-screening tests for individuals are considered essential and are covered in full by Medicare in all provinces. Screening rates for breast, cervical, and colon cancer are all higher than the average for developed countries, as are childhood vaccinations and rates for seasonal flu shots.

PAYMENT

Payment in Canada is considerably more variable than in many other developed nations due to the decentralized provincial model. Although the majority of hospitals are reimbursed through global budgets, there has been some recent movement toward activity-based payments in several provinces. Also, most physicians are paid on a fee-for-service basis by Medicare or private insurance, but physician services in a variety of settings—notably primary care—are beginning to transition to alternative payment models such as capitation.

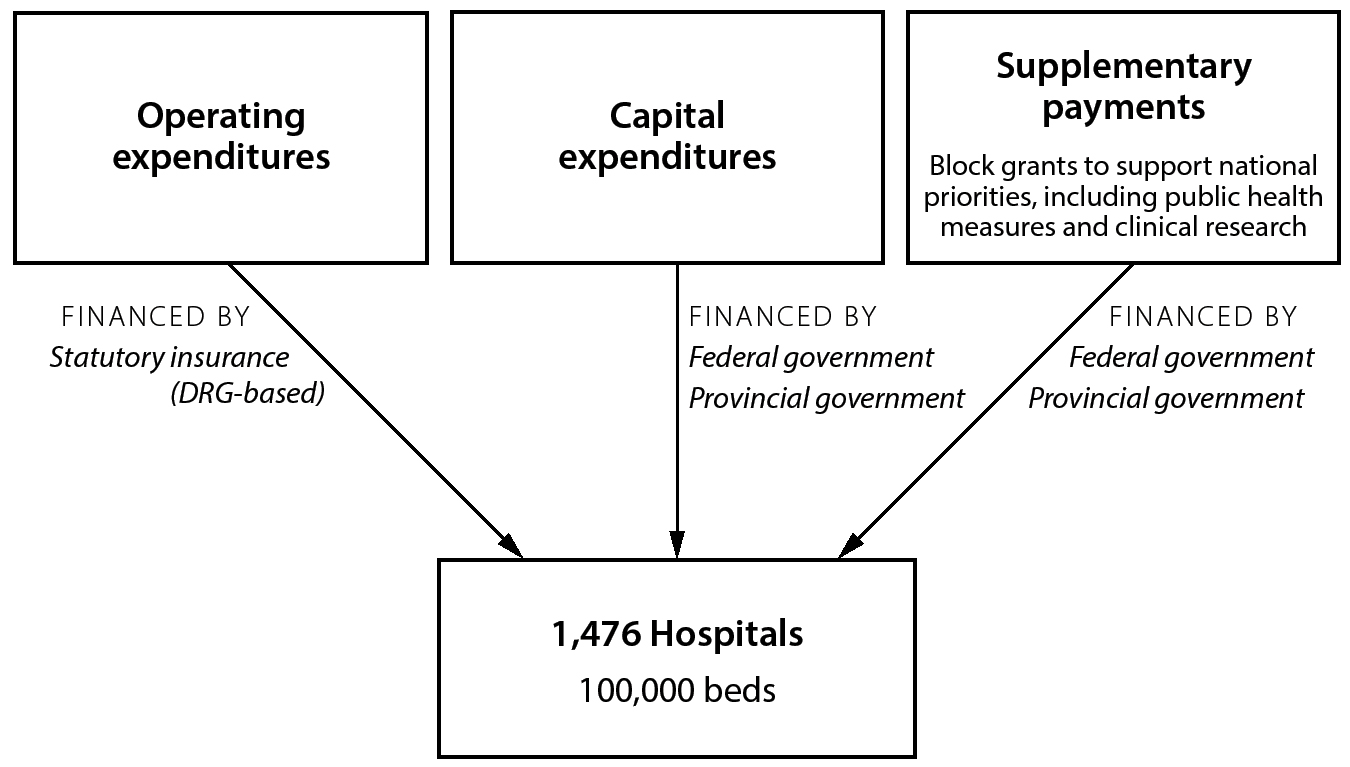

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (Canada)

Payment to Hospitals

Global budgets negotiated by provincial governments primarily cover inpatient services, although several provinces have begun experimenting with activity-based payments.

Funding for inpatient services generally flows from provincial ministries of health to provincial or regional health authorities before being allocated to individual hospitals and other facilities. Provinces collect taxes and designate funds to sub-provincial regional health authorities as a mix of unrestricted block grants (traditionally on a per capita basis) and targeted line-item funding tied to specific policies. Regional health authorities then divvy up their funding to specific hospitals, long-term care facilities, and other community-based providers. Importantly, although significant sums of money continue to flow through these regional agencies, much of these funds are constrained. For instance, in Ontario 36% of public funding is tied to hospital funding.

Lately there has been movement toward greater centralization. Alberta dissolved its regional health authorities in 2009 and established a single, province-wide authority referred to as the Alberta Health Services. Ontario consolidated its 14 LHINs into a single agency, Health Ontario. By contrast, Quebec still maintains 22 territorial health authorities.

Regardless of the exact funding route, the majority of hospital payments in all provinces remains global budgets. In this arrangement, the funding for each hospital is based on historical spending with annual adjustments that consider inflation and the growing cost of medical care. Hospital funding is not adjusted for the number of patients, complexity of procedures, or quality of care provided. It also does not incentivize improvements in efficiency or outcomes. Given Canada’s high-profile struggles with wait times for elective procedures, such arguably archaic payment mechanisms have come under intense scrutiny. However, as described by Dr. Allan Detsky, global budgets have stuck around because they can be appealing from both cost-control and predictability perspectives:

Global budgeting is successful at one main thing: capping costs. If you’re the Ministry of Finance, you love global budget because you look at last year’s budget and increase it by a certain percent… this system works to control costs and anything that you do for volume-based reimbursement goes away from predictable funding and opens the door to the same problems as fee-for-service.

There has been some progress: a handful of provinces have incorporated elements of activity-based payment, in which hospitals are paid for services that they complete rather than a fixed annual budget. In 2010, British Columbia became the first province to tie 20% of its hospital payments to activity. Since then both Alberta and Ontario have also introduced elements of activity-based payments. The Ontario system ties roughly 30% of hospital payments to activity through its Quality-Based Procedure program. This program pays hospitals a fixed amount for each patient they provide care for, provided the patient has one of 10 targeted conditions. These include a mix of common surgical and medical conditions, such as major lower extremity joint replacement, stroke, pneumonia, and congestive heart failure exacerbation. There have also been several pilot programs toward bundled payments for entire episodes of care. The largest of these, known as the Integrated Comprehensive Care Project in Ontario, was launched in 2013 and offers bundles for both surgical and medical procedures.

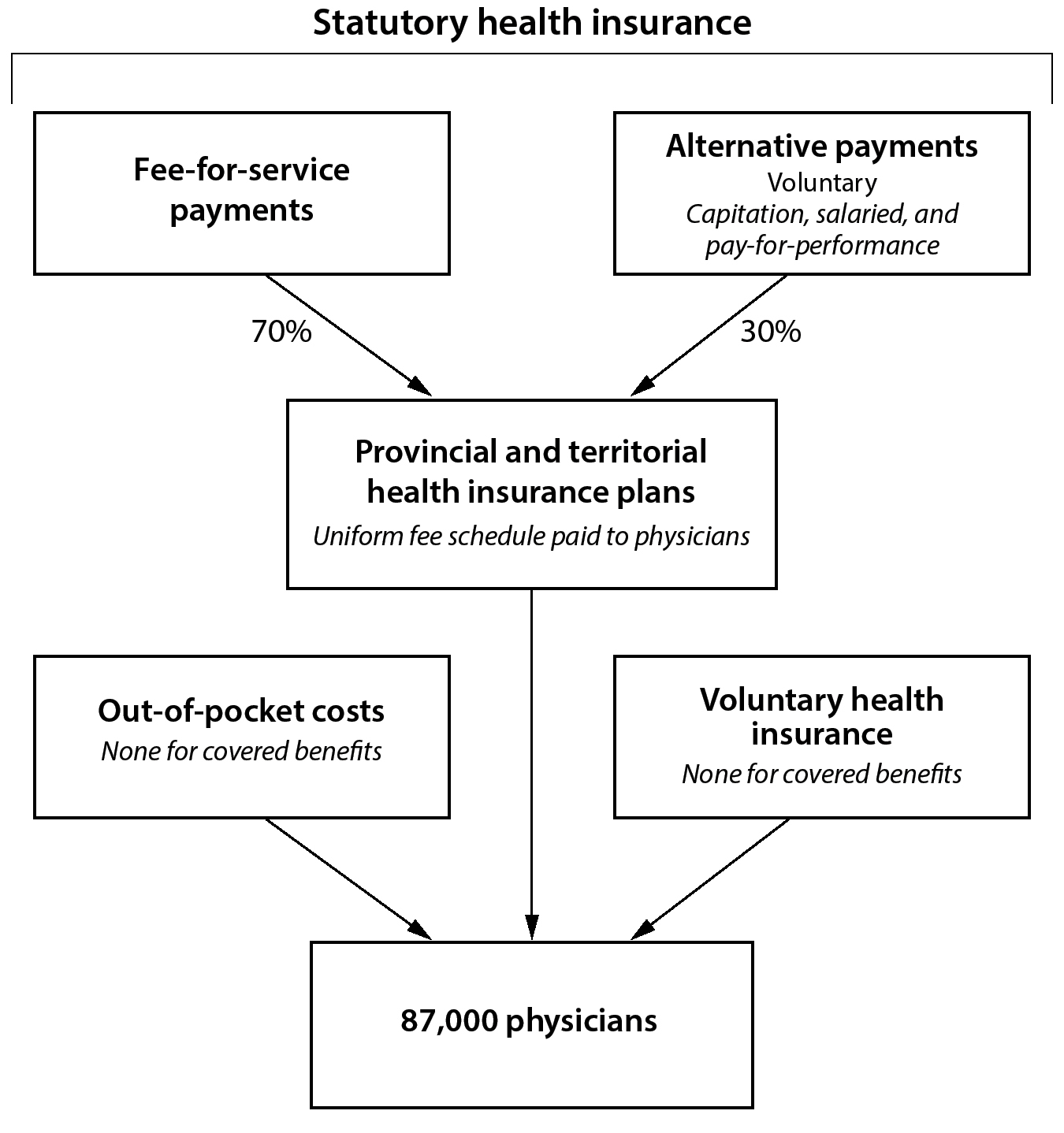

Figure 4. Payment to Ambulatory Physicians (Canada)

Payment to Physicians

Reimbursement is highly variable among provinces. However, fee-for-service remains the dominant form of payment for physician services, accounting for roughly 70% of physician payment. There are also a variety of alternative payment models, including capitation, salaried wages, and performance-based payments.

Variability is high because both provincial ministries of health and individual group practices have the right to negotiate their own contracts. Each provincial ministry of health not only publishes its own fee schedule but can also offer physicians myriad alternative payment arrangements. At the moment these alternative payment models are all voluntary. Simultaneously, individual physicians are privately employed and can either accept the fee schedule or attempt to negotiate their own payment arrangement.

Canadian fee-for-service is similar to other nations’ fee-for-service except that individual provinces are tasked with negotiating their own fee schedule with the appropriate professional society. And if the 2 parties fail to agree to terms, provinces have the right to unilaterally set prices. For instance, every few years in Ontario the Ministry of Health and Ontario Medical Association negotiate a new Physician Services Agreement that establishes a fee schedule. Although the fee schedules in Canada tend to be somewhat simpler than those in the United States, there are variations in classification and amount paid, making comparisons between provinces challenging.

As for alternative payment models, the most recent wave of interest dates back to the early 2000s, when Ontario introduced a wide-scale capitation model for primary care services. The program offered capitated payments with incentives for primary care physicians to form group practices and, among other things, offer reliable access to after-hours care. Although the program was intended to be mandatory, this was politically unfeasible. Consequently, it was rolled out with voluntary enrollment. Not surprisingly, adverse selection occurred, and only providers without many medically complicated patients enrolled. As Dr. Detsky explained,

Nothing’s been successful… to have political agreement it had to be voluntary. But then any physician can figure out their own work-to-pay ratio. If you only saw young healthy people, you’d go for [the capitation model]. If you saw medically complicated patients, you’d pass [and keep fee-for-service].

Still, there remains significant interest and experimentation, especially for primary care reimbursement. Ontario is trying 8 different alternative payment models for primary care physicians alone. Moving specialists away from fee-for-service remains a challenge, but there have been some early pilot studies with bundled payments.

Payments for Long-Term Care

Long-term care is paid through a mix of traditional mechanisms. Medical services are generally paid directly as fee-for-service under Medicare, while housing, accommodation, and custodial services are generally paid at a fixed daily rate. The federal government supports in-kind home care through its Compassionate Care Benefit, which allows for 6 weeks of paid leave for all workers who have a family member in their last 6 months of life.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

As the majority of complementary and alternative medicine services are not deemed medically essential, Medicare does not reimburse these services, and few provinces include them in their benefits packages. This means the majority of complementary services and alternative medicines are paid for either by private insurance or individual out-of-pocket costs.

Preventive Medicine

Most vaccines and recommended screening tests are paid for by Medicare on a fee-for-service basis without coinsurance.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

While Canadian health care is largely publicly financed, the provision of care remains almost exclusively private. Almost all medical practitioners are self-employed, and the majority of hospitals are private and not for profit. Given this high degree of autonomy, fragmentation of care remains a major issue.

Hospital Care

Canada has 1,476 hospitals, with a total of around 100,000 beds for 37 million people, equal to 2.7 hospital beds per 1,000 inhabitants. Similar to other countries, there has been a steady decline in the number of hospital beds in Canada since the 1990s.

The vast majority of acute care hospitals (95%) are private, not for profit. These hospitals also provide the vast majority of medically essential services covered under Medicare. Most are run by regional boards appointed by provincial health authorities, although many have private boards that operate under contract with provincial health authorities. Many solicit charitable donations to fund capital expenditures, but their operating expenses are paid for almost exclusively through the provincial governments. Hence, hospitals and provincial ministries of health are intimately tied together.

The remaining handful of hospitals are private and for profit. These for-profit hospitals are not legally allowed to provide services covered under Medicare and several provinces have statutes prohibiting physicians from working simultaneously at for-profit and not-for-profit hospitals; their role remains minimal and focused on services not covered under Medicare.

Ambulatory (Outpatient) Care

Outpatient care is centered on primary care physicians, who serve as care coordinators and relatively strong gatekeepers. At a rate of 7.7 annual consultations per person per year, Canadians visit physicians slightly more than other developed countries and nearly twice as much as patients in the United States. Similarly, Canadian physicians see on average around 3,100 patients per year, around 15 patients per day for a 200-day work year. Almost all physicians are privately employed, including hospitalists.

Primary care physicians are the first point of contact for the majority of patients, and primary care physicians are tasked with coordinating their care. The majority operate in small-group practices; fewer than one in 6 remain true solo practitioners. They are paid fee-for-service, although several provinces have begun to incentivize the formation of integrated care networks, each with its own name: in Alberta these are known as Primary Care Networks; in Quebec, Family Medicine Groups; in Manitoba, Physician Integrated Networks; and in Ontario, either Family Health Groups, Family Health Networks, or Family Health Organizations. All of these programs incentivize integration of care between physicians and other nonphysician providers by using mixed payment models.

Despite these promising strides toward more integrated primary care, fragmentation remains a huge problem. According to David Rudoler, assistant professor at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology,

Everywhere fragmentation is the rule and it’s a major issue we’re dealing with. At least in Ontario, physicians run independent practices and are private business owners, so the vast majority of primary care is delivered by independent, privately-owned physician practices. There is very little in terms of accountability to the provincial government or regional bodies. Although that has changed in the last couple years with Family Health Teams, there has been little attempt to integrate community services with other sectors of the health care system. For the vast majority, little has changed.

Medical and surgical specialists are even more independent. Almost all are privately self-employed, and each specialty is largely self-regulated through their own professional societies. The majority (65%) work primarily out of hospitals, while only 24% work out of an office or clinic. They are free to open a new practice anywhere they would like, and provincial governments have almost no authority to regulate specialists.

Although access to specialists generally requires a referral from a primary care physician, referrals last for 2 years, and primary care physicians have no direct financial incentive to consider total cost of care. Referral networks are mostly organic, forming from personal relationships and geographic proximity. (Outcomes data at the individual level is difficult to obtain, and even if it were available, there is no specific incentive to guide patients to higher-value providers.) Moreover, once a patient has a referral, they are “in” the system, and specialists are allowed to refer them to other specialists.

From a patient’s perspective, the Canadian system is quite attractive. Except for queues for some elective procedures, Canadians are allowed to visit any primary care physician in any province without any cost sharing. They can also see any specialist for whom they have a referral without any cost sharing.

Mental Health Care

Like other developed countries, since the 1980s Canada has undergone a process of deinstitutionalization for mental health services. The majority of mental health care is now provided on an outpatient basis. However, there is a strong division between physician-provided mental health care and therapist- or social worker–provided mental health care.

Physician-provided mental health care is considered essential and is, therefore, covered by all provincial Medicare plans. Non-physician-led mental health care is not covered by Medicare plans. Therefore, payment for therapists, social workers, and occupational therapists is left to provincial plans, private health insurance plans, or out-of-pocket costs.

A recent but growing innovation is for family care networks to employ in-house mental health professionals. In Ontario, Family Health Organizations can apply for funding to incorporate a psychologist for their patients, and physicians who roster a patient with a known severe mental illness can receive a one-time bonus payment. Coordination for patients with mental health services is poor. It is not uncommon for these patients to become lost in the system.

Long-Term Care

Compared to other countries, Canada has a high percentage of inpatient beds dedicated to long-term care (20%, compared to the OECD average of 13%). But, with its aging population, there remains concern over a bed shortage. Long-term care is not guaranteed under the CHA, and both private and public institutions provide long-term care. The prevalence of each varies by province, with some provinces, such as British Columbia, having the majority being private and not for profit, while others, such as Ontario, having mostly private, for-profit, long-term care facilities. Of the 636 long-term care homes and 117 hospital-based continuing care facilities in Ontario, 51% are private and for profit, 27% are public, and 22% are private and not for profit.

Preventive Medicine

Privately employed ambulatory physicians typically perform screenings and immunizations, although citizens can also receive some vaccines directly through regional health agencies. Both the provincial and national governments spearhead their own campaigns to improve public health, including largely successful campaigns to increase screening rates for breast cancer and colon cancer.

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

Canada is the world’s 9th largest pharmaceutical market, with around $30.2 billion USD ($39.8 billion CA) in annual sales. This translates to 16% of total health care expenditures, or $823 USD ($1,086 CA) per person. This is the 3rd-highest per capita spending in the world, and it’s rising rapidly—around 4% per year.

Coverage Determination

For a new medication to be approved, it must first be determined to be safe and effective by the Health Products and Food Branch (HPFB) of Health Canada, analogous to the United States’ FDA within the Department of Health and Human Services.

First, pharmaceutical companies submit a New Drug Submission (NDS) to the HPFB that contains the scientific data to support use of a medication for a specific aim. The application is referred to the proper directorate—either Therapeutic Products or Biologics and Genetic Therapies—and then to the appropriate bureau for review. For instance, a novel statin would be referred to the Therapeutic Products director and be reviewed by the Bureau of Cardiology, Allergy, and Neurologic Sciences. The bureau assesses the safety and efficacy of the new medication as well as the quality of data behind it. It also has the ability to review the new product’s proposed packaging and labeling. However, the committee does not look at the medication’s economic impact. Unlike the FDA, this process occurs behind closed doors; there are no standard public hearings.

If the HPFB committee determines that a drug’s benefits outweigh its risks, it issues a Notification of Compliance (NOC) and a Drug Identification Number (DIN) that allows for sale of the medication. If the committee determines that the benefits do not outweigh the risks, the medication is not legally allowed to be prescribed. This process takes, on average, one year to complete.

Price Regulation of Branded Medicines

After HPFB determines the medication to be safe and effective, a 3-step process sets the prescription drug’s prices. First, the Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB) sets a maximum national sales price using reference pricing. Second, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) assesses the medication’s cost effectiveness and publishes a report, the Common Drug Review (CDR). Finally, public drug plans—provincial, territorial, and federal—negotiate the final confidential sales price with pharmaceutical companies through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA).

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (Canada)

The Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB) begins by classifying the benefit of the new medicine into one of 4 categories: breakthrough, substantial improvement, moderate improvement, or slight or no improvement. Breakthrough medications are truly innovative products without competitors in the same therapeutic category. The degree of improvement for drugs with competitors is based on a holistic review that includes improved outcomes and reductions in adverse events.

The PMPRB then compares the proposed factory price to (1) what other nations pay for the same drug and (2) what Canadian provinces pay for therapeutically similar drugs. By statute, the PMPRB compares the proposed price to that paid by a group of 7 nations, referred to as the PMPRB-7: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, UK, and the United States. The PMPRB also compares the proposed price to what is being charged domestically for other medications in the same therapeutic class. For instance, if another statin is introduced, its proposed price would be compared to what is being charged domestically for atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and all other statins.

The PMPRB concludes its analysis by calculating a maximum average potential price (MAPP), above which the proposed price would be deemed excessive. For breakthrough medications, MAPP is set as the average price paid in the 7 comparator countries. For medications with substantial improvement, MAPP is set as the higher of either the average price in PMPRB-7 or the highest price paid domestically for substitutable therapy. And for medications with slight or no improvement, MAPP is set as the lower of either the average price in PMPRB-7 or the highest price paid domestically for substitutable therapy. If the introductory price is deemed excessive, pharmaceutical companies can either voluntarily reduce the price or appeal. This is rare, however, because pharmaceutical companies can calculate the MAPP themselves and set their factory price to just under this ceiling.

In August 2019, Canada amended the Patented Medicines Regulations to remove the United States and Switzerland from the PMPRB’s basket of countries used for reference pricing, beginning in July of 2020. The amendments also will allow the PMPRB to consider the actual market price of medicines in Canada—as opposed to only the proposed factory price—as well as whether the price of a drug actually reflects its value for patients.

Once the PMPRB gives its maximum price, the CADTH takes over. It conducts a national cost-effective analysis, known as the Common Drug Review (CDR). In this report, the CADTH reviews the clinical and economic data behind the medication and compiles a Clinical Report and a Pharmacoeconomic Report, with nonbinding pricing and coverage recommendations to the provincial and territorial governments.

The final sales price is set through negotiations between provincial Medicare plans or private insurers and pharmaceutical companies. Although provinces have traditionally negotiated individually with pharmaceutical companies, since 2010 all provinces except Quebec have been in the pCPA to negotiate jointly. Quebec, the one exception, has a “most-preferred” clause that only allows pharmaceutical companies to sell them medications at the lowest price offered anywhere in Canada. While they are not technically part of the agreement, then, they de facto benefit from the negotiations.

For branded medications, the pCPA negotiates rates with pharmaceutical companies individually. By combining all provinces’ buying power, the pCPA has lowered branded pharmaceutical prices and decreased price variation between provinces. Given the concentration of Canada’s populations in several provinces (nearly two-thirds live in Ontario and Quebec alone), this has been especially beneficial to the smaller provinces and territories.

For generic medications, the pCPA uses a tiered pricing framework based on the number of generic manufacturers on the market. If a new generic is the only one on the market, its price is set at 75% of the brand listing. Once a 2nd generic is introduced, the price of both decreases to 50% of the brand price. Upon entry of a 3rd generic, the prices all decrease to either 25% for oral solid medications (pills) or 35% for nonoral medications (liquid oral, inhalers, etc.). Since its creation the pCPA has lowered generic drug prices by over 50%.

Private insurance plans are free to negotiate their own rates for branded and generic medications. However, as described by one expert I spoke with, “They’re more generous and usually just accept whatever price is offered.”

While recent reforms, including the CDR and pCPA, have been widely acknowledged as successful in increasing uniformity and reducing prices, the PMPRB is highly controversial. In particular the PMPRB-7 includes some of the highest-paying countries and—until the 2020 reform—included the 2 highest paying countries of all, the United States and Switzerland. The reason is intimately tied to history. Before 1987 Canada kept pharmaceutical drug prices exceptionally low through a practice known as compulsory licensing: the government allowed for domestic generic production of branded pharmaceuticals immediately after approval in exchange for a 4% royalty to the patent holder.

Not surprisingly, this was unpopular with trading partners that had significant pharmaceutical interests. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) ended the practice and replaced it with the external reference pricing through the PMPRB. The PMPRB-7 were then selected not as a way to control costs but as part of a quid pro quo in an effort to attract pharmaceutical R&D investment in Canada. As described by one Canadian professor,

At that time, pharmaceutical brand companies were mostly subsidiaries of European or US drug companies like Pfizer or AstraZeneca. Those companies essentially said, “Canada, we’re going to substantially increase our R&D footprint. But if you want to be in the club with the US, UK, Germany, Sweden, and France, you’re going to have to allow higher prices.” The conservative government at the time believed that this was a good tradeoff. In the House of Commons debate, [Prime Minister] Mulroney said, “Let’s not lose out on the biotechnology revolution” and make this a Silicon Valley in the north. So domestic drug prices were set to be in line with drug prices in countries that had substantial pharmaceutical R&D sectors.

In the years since, there have been multiple reforms suggested, including switching the reference countries to lower-cost nations, including Spain and South Korea, and using cost-effective analysis. None were successful until the 2020 reforms were passed to shift reference pricing from the highest paying to more comparable countries.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

While physicians are free to prescribe any drug approved for sale by Health Canada to any patient for any indication they see fit, professional and financial regulations restrict prescribing. First, just because a physician prescribes a medication does not mean Medicare or private insurers will reimburse its purchase. Medications must be on a formulary to be reimbursed, and public plans have the power to either not list or specify reimbursement criteria for certain prescription drugs. Off-label prescribing is allowed, but reimbursement is variable. In some cases, patients may need to pay out of pocket.

Second, pharmacists can freely substitute generics without physician consent. For instance, if a physician prescribes a branded antihypertensive while a generic equivalent is available, pharmacies can—and do—switch to the cheaper generic alternative. Not only is the pharmacy incentivized financially to do this by pocketing the difference, but so are patients; provincial Medicare plans will not pay for more than the cost of the generic. In fact, in Ontario the only way a physician can prevent automatic substitution is filling out a special form outlining the clinical rationale for the branded drug and a subsequent form reporting adverse events from the generic. These policies have helped Canadian generics capture a 70% market share by volume, almost as high as the United States’ exceptional share.

Prices Paid by Patients

Outpatient medications as well as over-the-counter medications are covered through a mix of provincial plans (45%), private plans (35%), and out-of-pocket costs (20%). These represent a large and growing share of health expenditures and remain a challenge for Canadian policymakers.

All inpatient pharmaceuticals are completely covered without co-payment through Medicare. Patients are also not responsible for any sales taxes on these.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

There are nearly 90,000 practicing physicians in Canada. This represents 2.4 practicing physicians per 1,000 inhabitants, lower than the OECD average of 3.5 per 1,000 people. About 42% of physicians are women, and just over a quarter received their medical training outside of Canada. Nearly half (47%) are generalists, significantly higher than the OECD average of 30%. The vast majority are privately employed, even those who are employed in hospitals.

Canadian physicians are well compensated. As of 2016, the average income was $193,000 USD ($225,207 CAD) for a primary care physician, $276,000 USD ($364,959 CAD) for a medical specialist, and $347,000 USD ($458,843 CAD) for a surgeon. The highest compensated specialists, ophthalmologists, earned $539,000 USD ($712,728 CAD), while the average among all physicians was $256,000 USD ($338,513 CAD).

As with other developed countries, Canada faces a serious maldistribution of physicians. Whereas 19% of Canadians live in rural areas, only 14% of primary care physicians and 2% of specialists live in rural areas. Especially in the northern territories and rural areas of the southern provinces, it has been hard to recruit physicians to move and impossible to force them to do so, given their status as independent, privately employed practitioners. Although provinces have attempted to attract physicians by offering higher compensation in the form of capitated payments, guaranteed salaries, higher fee-for-service rates, and lump-sum bonuses, little progress has been made. Some provinces, such as Saskatchewan, have begun to rely heavily on foreign medical graduates, while others have empowered nurse practitioners to set up supervised practices in these areas.

There are 17 medical schools in Canada that together train around 2,300 physicians each year. Provincial governments set the number of training spots available each year (numerus clausus). Prior to entering medical school, applicants generally must complete at least 2 years of higher education. The majority of medical schools last 4 years, although 2 offer 3-year tracks, and they are structured similarly to the US system of 2 years of preclinical classroom work and 2 years of clinical training. Graduating students apply through a match process identical to that in the United States and enter residency for anywhere between 2 (family medicine) and 6 years. Medical school costs students around $11,400 USD ($15,000 CA) per year, although it varies significantly by province.

Nurses

As of 2015, Canada had 9.5 nurses per 1,000 inhabitants, in line with comparable countries. As in most other countries, there remains a concern of an impending nursing shortage.

Going back to 1967, Canada has a long history of advanced practice nurses. The Canadian government recognizes 2 forms of advanced practice nurses: nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. Nurse practitioners directly manage patients and specialize in a field of medicine, similar to the United States. Clinical nurse specialists also specialize in a subfield and assist in developing nursing guidelines. Both require graduate degrees.

Registered nurses in Canada make an average of $54,000 USD ($71,405 CAD) per year, less than the average wage for US nurses. By contrast, advanced practice nurses can earn up to $120,000 USD ($158,768 CAD) per year. Becoming a nurse in Canada is similar to becoming a nurse in the United States and requires a bachelor’s degree.

CHALLENGES

There is much to like about the Canadian health care system. Patients have truly universal coverage, with free choice of doctor, direct access to specialists, and no cost sharing for necessary medical services. Physicians have high wages, professional autonomy, and a relatively efficient billing system. And although costs are high, they are far from the highest, while providing high-quality care with no cost sharing.

Still, there remain several key challenges.

The most glaring deficit in Canadian Medicare programs is their lack of universal coverage for pharmaceuticals. Canada remains the only developed country to not include outpatient pharmaceutical coverage in its statutory plan. While well intentioned, provincial plans offer a porous safety net that lets select populations fall through while only marginally helping others in need. Given Canada’s lack of cost sharing for any other medically necessary services, this omission is striking and problematic. Efforts to remedy the situation have consistently failed.

Pharmaceutical pricing also remains tied to a reference pricing mechanism intended as an incentive for pharmaceutical companies to invest in Canada that failed. Although external reference pricing has been used successfully in other countries, such as Norway and Taiwan, tying pharmaceutical prices to 7 of the most expensive countries in the world seems unjustifiable. The creation of the pCPA and CDR to aggregate all provincial buying power to increase the leverage in price negotiations are strong steps in the right direction, and the 2020 reforms have eliminated the 2 highest paying countries. Only time will tell whether the set of 11 countries selected will satisfactorily curb pharmaceutical spending. The potential for stronger central regulation of pricing is also palpable. With growing pharmaceutical expenditures across all developed nations, the pressure for further reform will only continue to gain steam.

Third, Canada’s health system remains largely fragmented as a result of its provincial model and strongly independent physicians. Primary care physicians’ strong role and their incorporation into interprofessional practice is a strong step in the right direction, but networks remain underdeveloped. Continued experimentation with alternative payment models for primary care providers—and specialists—will eventually have more success and lead to a higher quality of chronic care management.

Fourth, the hesitancy to transition to activity-based payments for hospitals has helped perpetuate significant wait times for many elective procedures. Although wait times in Canada are often overblown by conservative commentators and media in the US, they do exist and can be a problem. Broader adoption of activity-based payments and quality-based incentives could help improve hospital efficiency, decrease wait times, and, potentially, improve quality.

Finally, as with other countries, Canada’s health system has yet to figure out how best to finance long-term care for its citizens and for patients with mental illness.