CHAPTER FOUR

NORWAY

While living in Norway, Vanessa developed new onset ulcerative colitis. She never selected a general practitioner, so when she got sick she had to call the urgent care center:

While the healthcare professional on the other end of the line was super nice and understanding, [the doctor on duty] did not share my sense of urgency. [Instead he] arranged an appointment at a local GP office for me—who, in turn, sent me to the emergency room straight away.

During this first emergency room visit she was misdiagnosed and sent home, but her symptoms later worsened. The same GP referred her to the ER a 2nd time, where she was “finally admitted to the hospital and got a diagnosis one day later. [For all] this I mainly have to thank the GP who took me on even though I wasn’t on his patient list… and who took me seriously right from the beginning and made sure to call the hospital.”

In Vanessa’s view the Norwegian system functions well. Although she could not get admitted to the hospital or see a specialist without either a life-threatening condition or a referral from a GP, she describes all the health care professionals who cared for her as very nice, and they never appeared rushed or stressed. And her medical treatment was low cost. A visit to a GP’s office cost her $16 USD (150 kroner), an X-ray $27 USD (250 kroner), and a visit to the emergency room had a $38 USD (350 kroner) co-pay.

All this sounds very appealing, yet a major problem with the Norwegian health care system that seems to trouble everyone is waiting times. If you do not have an urgent problem, there are waiting times for specialist care. In March 2018 the average wait time in Norway to receive a specialist appointment was 57 days.

HISTORY

Norway is a small country with a population of 5.3 million. Beginning in the early 1970s North Sea oil production made it one of the world’s richest countries per capita. As is typical in Scandinavia, it has an extensive, well-financed social safety net.

But these developments are relatively new. In the 19th century, Norway had few natural resources, relied on farming and fishing, and was ruled by Sweden. In 1838, elected municipal councils were established. Following the workers protests that swept Europe in 1848, trade unions were created and demanded legal equality regardless of social class.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Norwegian municipalities, the Lutheran church, and voluntary organizations established hospitals. Beginning in 1905, with full independence from Sweden, the Norwegian government enacted a series of social reforms, such as the 10-hour work day, unemployment insurance, and other worker protections. Modeled on Germany’s Bismarckian system, the Compulsory Sickness Insurance Act of 1909 created a subsidized health insurance scheme but covered only workers.

After World War II Norway began consolidating its social democratic welfare state. In 1967, Norway enacted legislation to combine the many social insurance schemes for pensions, disability, sick leave, and other areas into a unified National Insurance Scheme (Folketrygden [NIS]) that was compulsory for all Norwegian residents, including noncitizens. The NIS became fully functional in 1971, and the Ministry of Labor administered it.

Beginning in the late 1960s the health system was repeatedly reorganized to improve equality of access to treatment, efficiency, and health outcomes. In 1969, counties were entrusted with responsibility for building and managing hospitals. The Municipalities Health Services Act of 1982 gave municipalities responsibility for primary care services. The Patients’ Rights Act of 1999 gave Norwegians the right to choose a personal primary care physician and required local municipal councils to guarantee fulfillment of this right and to finance physician care. It also gave individuals a right to specialized health care services. Then, in 2001, the Health Authorities and Health Trusts Act was passed, shifting hospitals’ financing and operations from counties to the national government through newly created Regional Health Authorities (RHAs). In 2009, the Ministry of Health and Care Services, through the Norwegian Health Economics Administration (Helseøkonomiforvaltningen [HELFO]), assumed responsibility for the health care portion of the NIS budget.

Today 3 values govern the Norwegian health system: (1) universality, ensuring every Norwegian resident is covered for medical services; (2) full equality, ensuring access to health care regardless of geography and socioeconomic status; and (3) prioritizing children, ensuring that they get all care for free. Norway’s health system is predominantly—but not totally—socialized. The government owns most hospitals and employs the physicians, nurses, and other hospital-based workers. The government pays for all hospital care. The municipalities pay for primary care. But primary care physicians are self-employed, not government employees. In a somewhat complex system (detailed below), the physicians collectively negotiate fees with and are paid by the government. Dentists are also self-employed. The government pays about 85% of all medical care and 75% of the cost of prescription drugs.

Almost everything in the Norwegian health system is divided into 2. Yet, as one health policy report notes, the traditional distinction of “‘outpatient’ and ‘inpatient’ are not relevant for describing the health system in Norway. Instead, the 2 sectors are defined as primary care and specialist care.” Primary care is predominantly financed and overseen by the 356 municipalities. Conversely, 4 RHAs finance and oversee hospital and specialist care. The national Ministry of Health and Care Services, in turn, oversees the RHAs. This bifurcation extends to the payment for prescription drugs used in primary and specialized care. Counties are responsible for children’s and adolescents’ dental care. By providing payments to RHAs and block grants to municipalities, the Ministry of Health and Care Services essentially defines the national health care budget and priorities.

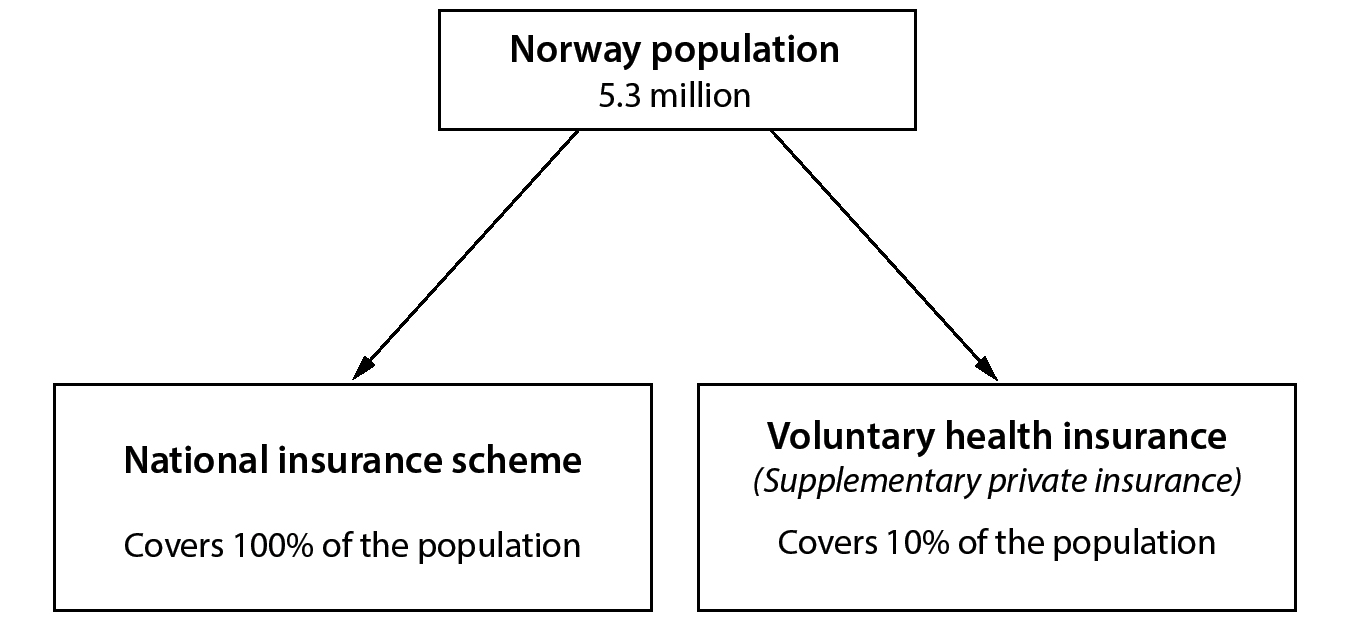

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (Norway)

COVERAGE

The Norwegian system is a public health insurance scheme with supplementary private insurance for a small minority.

The National Insurance Scheme (NIS) is comprehensive: it covers pensions, disability, unemployment, parental leave, and health care. All tax-paying residents contribute to the NIS and, thus, are automatically enrolled in NIS without needing to make a positive selection of an insurer or sickness fund—and without paying a premium.

There is also private health insurance, called voluntary health insurance (VHI). It does not cover any acute or emergency services, such as treatment for heart attacks, and is mainly used to avoid the wait times for specialist consultations and elective surgery.

FINANCING

Norway is the 4th-most expensive health care system on a per capita basis, but the cost is relatively low on the basis of percentage of GDP. Overall Norway spends $7,400 USD (64,400 kr.) per capita on health care. But because of a high GDP per capita ($75,500 USD PPP 2017), it spends only 10.4% of GDP on health care, about $39.1 billion USD (340 billion kr.) for 5.3 million people. Of this, approximately 85% is publicly financed, 15% is from out-of-pocket spending, and under 1% is from VHI.

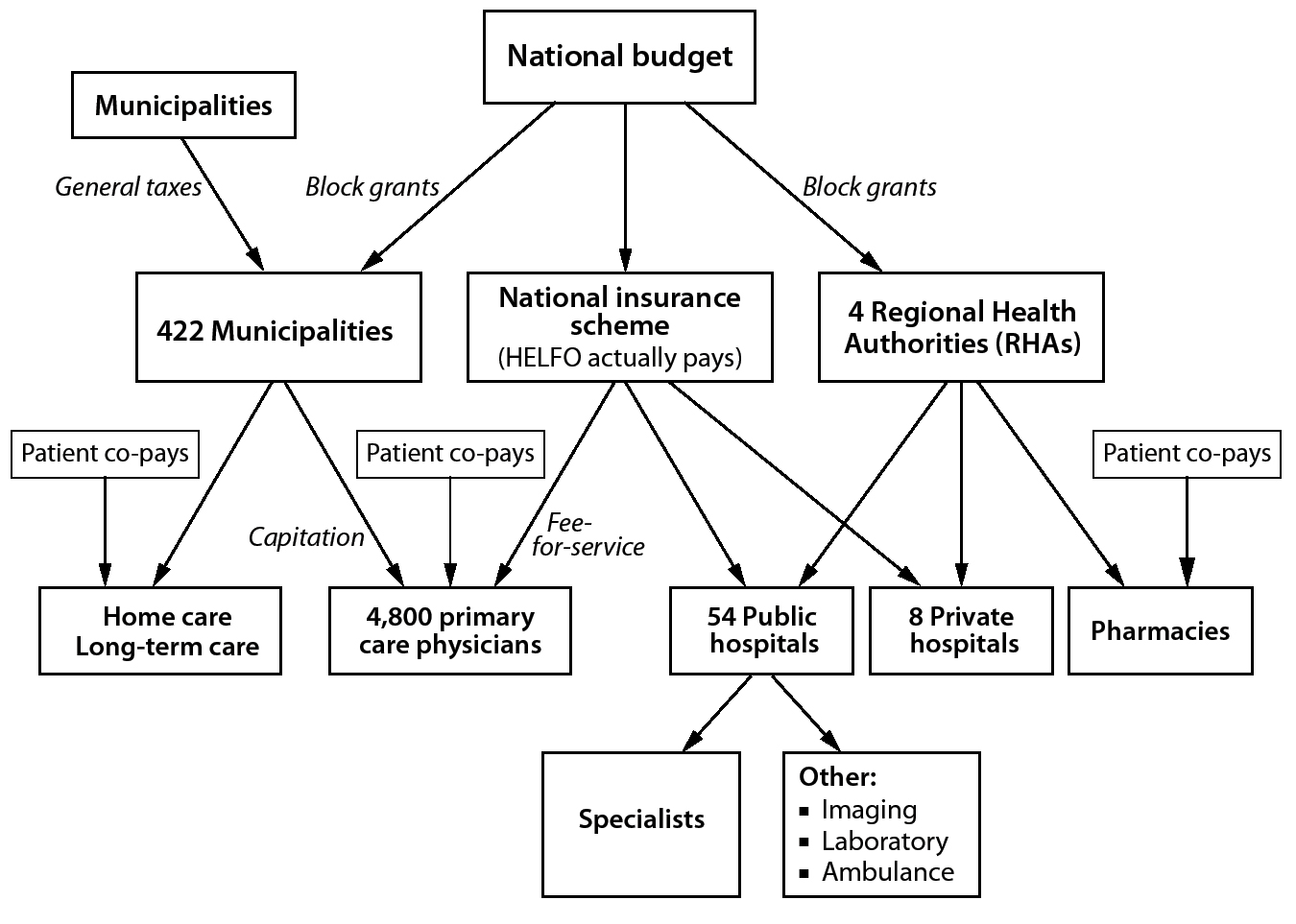

Figure 2. Financing Health Care: Statutory Health Insurance (Norway)

Public Health Insurance

There are 4 sources of financing for health care: (1) general taxes, including national, municipality, and county taxes; (2) NIS funds; (3) individual out-of-pocket payments; and (4) employer and individual payments for VHI.

There are no earmarked health-specific taxes, such as the payroll taxes used in Germany and for Medicare in the United States.

Municipalities finance primary care, preventive services, long-term care, public health, and palliative care. Primary care and preventive services are financed by a combination of (1) block grants from the national government to the municipalities, (2) municipal funds, (3) fee-for-service payments from the NIS, and (4) individual out-of-pocket expenditures. The national government’s block grant to municipalities is a single grant—without earmarks or allocations for specific services—that covers health care and many other municipal services, such as education. Municipalities determine how the funds will be divided among the various services they must pay for. They pay general practitioners’ capitation, about $46 USD (400 kr.) per person on the GPs’ panel list. The NIS also contributes to the financing of primary care by directly paying GPs fees for services rendered. NIS payments occur by transferring funds to the Ministry of Health and Care Service, which then gives the money to HELFO for actual payments.

From general tax revenues, the national government finances the 4 RHAs. The NIS also contributes funds to cover specialist consultations.

Counties pay 100% of dental care for children up to age 18 and 75% of dental care for young adults aged 19 and 20. Dental care for adults is totally private, paid 100% out of pocket by individuals. Similarly, children get free vision care, but adults pay 100% for vision care.

The Ministry of Health and Care Services sets an informal national budget for health care. It funds municipalities and RHAs for services. Beginning in 2013, the National System for the Introduction of New Health Technologies helps with setting priorities and ensuring high-value care by conducting Health Technology Assessments (HTAs) and cost-effectiveness studies of new drugs and other interventions.

Private Supplemental Insurance

About 10% of the population has VHI, but it constitutes only about 1% of health care spending. Employers provide about 90% of VHI through 8 for-profit insurers. Employers and employees receive no tax break for utilizing private insurance.

Long-Term Care

Currently 16.6% of the Norwegian population is over 65, with 10% over 70, and population growth is just under 2%. Long-term care, whether at home or in nursing homes, is financed by municipalities and out-of-pocket payments by the elderly.

Public Health

Municipalities pay for public health services. They fund GPs, who provide personal public health measures such as immunizations and cancer screenings. Municipalities are also responsible for school clinics and youth clinics that provide preventive services as well as the usual health education around nutrition, physical fitness, contraception, vaccinations, and other public health measures.

PAYMENT

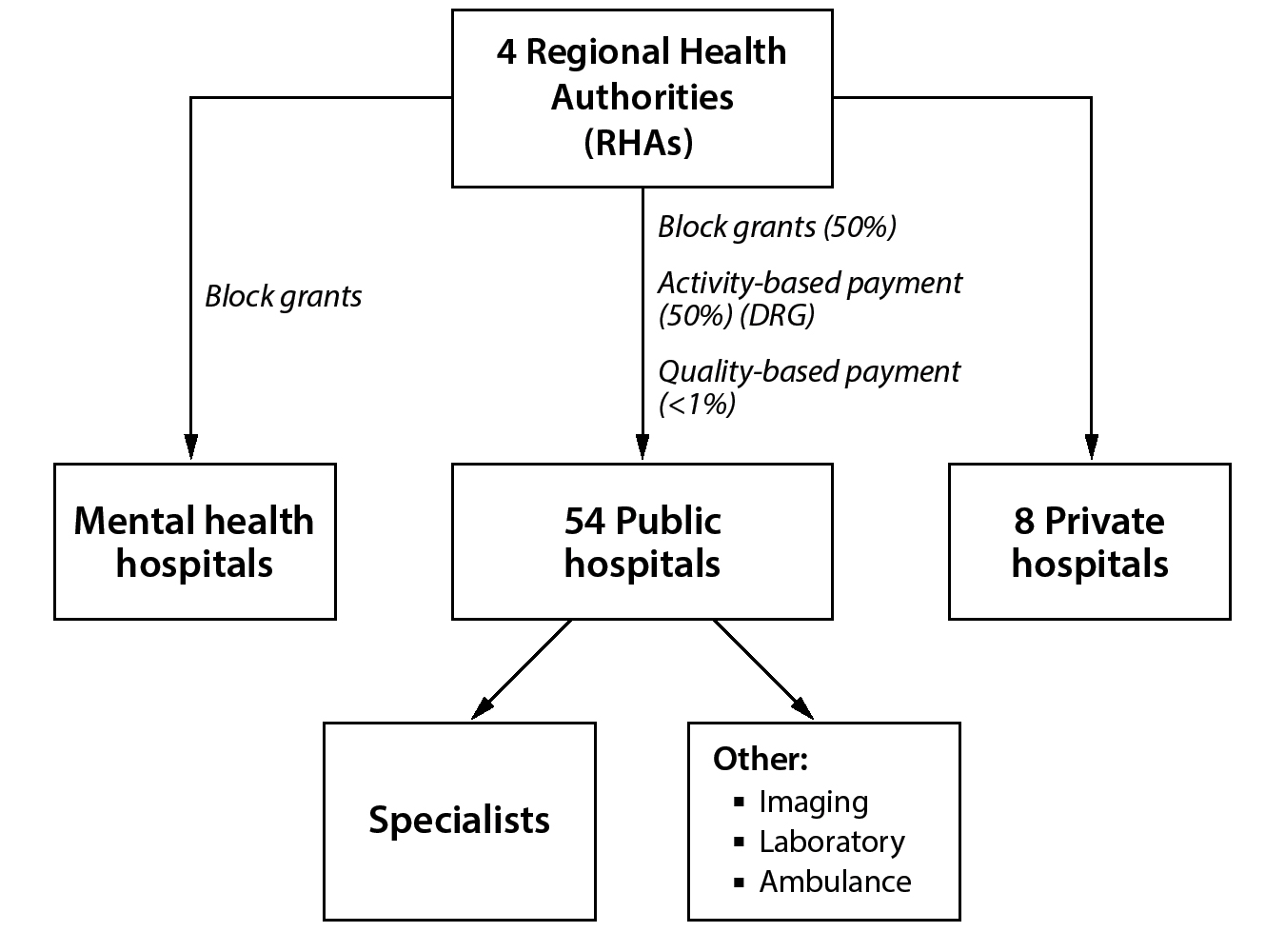

Payment to Hospitals

Overall, inpatient hospital services account for about 29% of all Norwegian health care expenditures. The dominant source of payments to hospitals is from the 4 RHAs, which, in turn, receive their money from the Ministry of Health and Care Services. The Ministry pays the RHAs in 4 ways:

1. About 70% of the revenue is paid as a block grant based on variables such as the types of services the hospital provides such as whether psychiatric services are provided, population size of the hospital catchment area, socioeconomic demographics, and health and mortality data.

2. About 27% of the payment to RHAs is based on services provided, also known as activity-based funding. The activity-based funding uses a Nordic version of the DRG system, with the weights based on average national costs.

3. Laboratory and radiology services are paid on a fee-for-service system, accounting for 2.3% of payments.

4. A quality-based financing payment is based on about 39 quality indicators; however, this method is less than 1% of hospital payments.

Each RHA determines for itself how to pay hospitals. As one official in the Directorate of Health noted, “There is no nationally determined system for the distribution of funds from RHAs to hospitals. [The RHAs] enjoy relatively large degrees of freedom to organize their activities and [in] how they use their funding.” In general, the 4 RHAs pay hospitals in the same way they are paid: a combination of block grants, activity-based financing, and quality incentives.

These funds cover hospital operations, including salaries, pharmaceuticals, and other hospital-based goods and services. However, radiology and laboratory services are funded on a fee-for-service basis. These payments also include ambulance, same-day surgery, and hospital-based specialists, such as oncologists.

Importantly, the RHAs are responsible for planning and financing hospital capital expenditures. In 2017, capital investment in the hospital sector was less than 4% of total hospital expenditures. RHAs have wide latitude to determine budgets for capital expenditures as well as to determine how they will be paid. The 4 RHAs established an Agency for Hospital Construction to help rationalize and improve hospital planning and construction. Hospitals also have some control over capital investments, such as for imaging equipment, and finance them from their regular RHA payments. There are some Ministry of Health and Care Services funds for special capital initiatives.

RHAs also contract with private hospitals to perform elective procedures that relieve waiting times. About 10% of RHA budgets have gone to purchase services from private hospitals and physicians.

Municipalities are required to pay a fee to the hospitals when a patient is ready for discharge but stays in the hospital awaiting a nursing home bed or another municipally controlled service. The Parliament sets the fee in the national budget—about $550 USD (4,780 kr.) per day. Patients have no financial responsibility—that is, no co-pays—for hospitalizations.

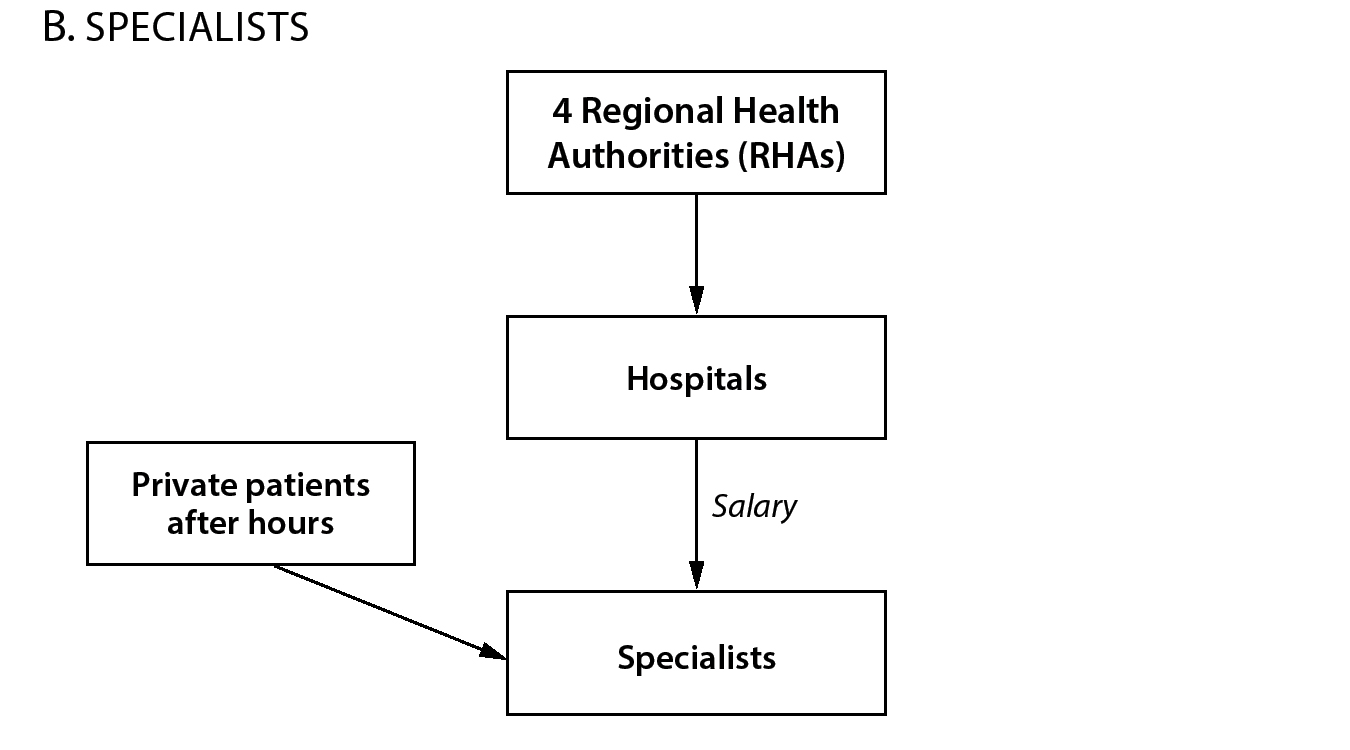

Payments to Specialists

There are 2 types of specialists—those based at hospitals and a few who are in private practice. Hospital-based specialists are salaried employees. After hours, however, they are permitted to do private consulting outside the hospital to supplement their incomes. In addition, there are a few totally private specialists. The number of private specialists is limited by the number of licenses, which are determined regionally. Individual patients and VHI pay for these private services, but RHAs may pay to supplement public care to reduce waiting times.

Negotiations between the Norwegian Medical Association and hospitals determine pay, hours, schedules, coverage, and other work details of hospital-based physicians. In 2016, there was a strike over working and on-call hours because hospital-based physicians wanted to retain schedule predictability and family time, while hospitals wanted more flexibility to modify on-call time. The Norwegian Medical Association won the court battle.

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals and Specialists (Norway)

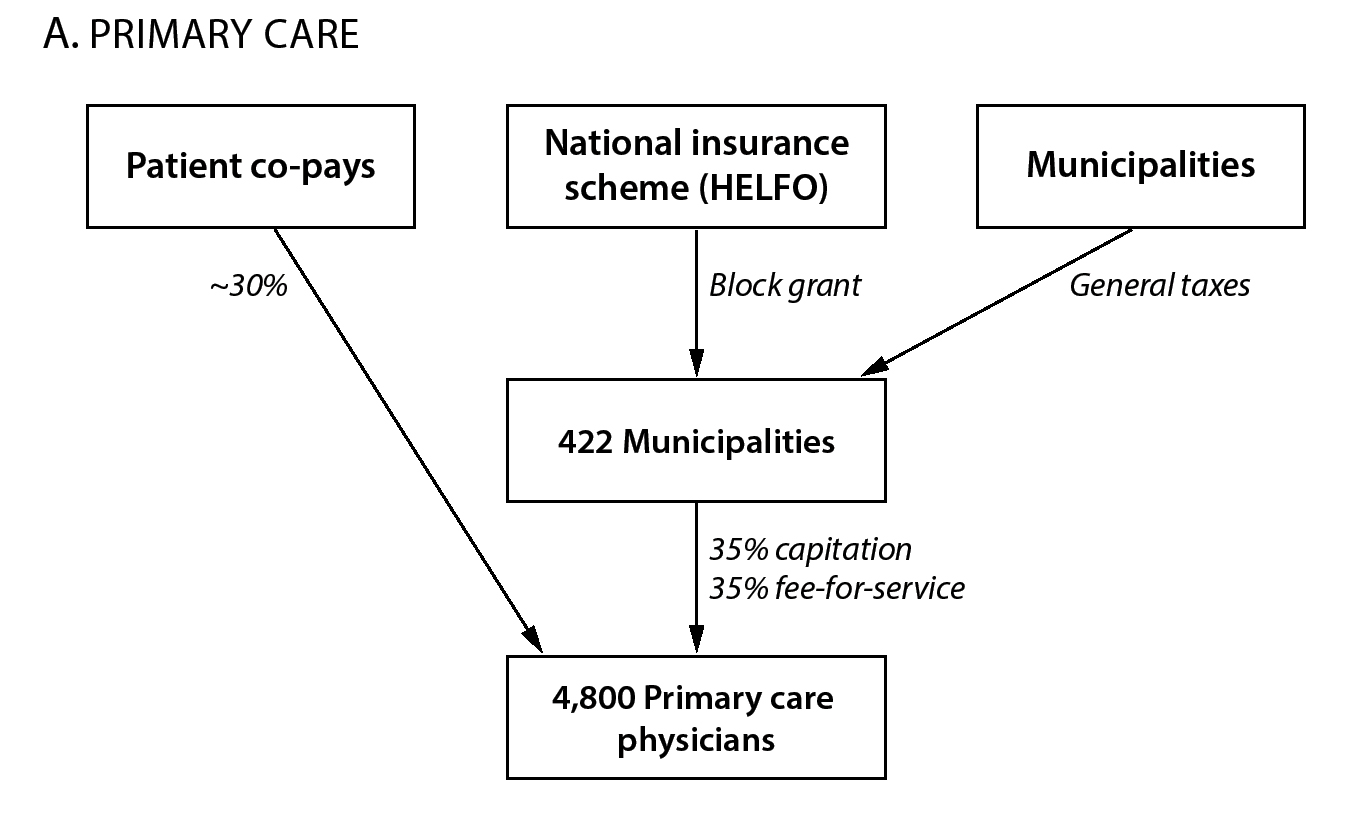

Payments to Primary Care General Practitioners

About 95% of GPs who provide primary care are private, self-employed workers, with the remaining 5% of GPs being full-time, salaried municipal employees. Primary care GPs are paid from 3 sources: (1) municipalities, (2) the NIS, and (3) patient co-pays.

GPs are required to take emergency calls for the municipality and could be required to work in the health and school clinics or municipal nursing homes. This municipal work is limited to one day per week, and they are paid a salary for these public health services.

Municipalities pay a capitated rate to GPs. This rate, about $46 USD (400 kr.) per patient, is not risk adjusted and accounts for about a third of GP income. Through HELFO, NIS pays on a fee-for-service basis to GPs for another third of their income. This amount has a small adjustment based on a patient’s health complexity. Finally, individual patient co-pays account for the remaining third of GP income. Patients have a required flat co-pay for seeing the GP, amounting to about $23 USD (200 kr.) per visit. There are various limits on this payment. Cumulative annual patient co-pays are limited to about $250 USD (2,170 kr.) per year. After that amount patients have no more co-pays for any services, and HELFO covers the co-pays for the GPs. Certain groups of patients are exempt and have no co-pays for GP visits, including children under 16, pregnant women getting pre- and post-natal care, and HIV/AIDS patients.

Figure 4. Payment to Physicians (Norway)

The capitation rate, fee-for-service, and co-pay rates are all uniform throughout Norway and are negotiated nationally between the Norwegian Medical Association, which represents all physicians, and the Ministry of Health and Care Services.

Payments for Mental Health Services

As with everything else in the Norwegian health system, payment for mental health services is bifurcated, although the bulk comes from RHAs. Part of their payment from municipalities and NIS comes when GPs provide mental health care for patients with mild to moderate conditions such as depression and anxiety. However, specialists at district psychiatric centers, general hospitals, or specialized mental health hospitals provide services for patients with moderate to significant mental health issues. Unlike other specialties, the block grant largely covers these institution-based mental health services and specialized drug addiction treatments. The activity-based payments, or DRGs, cover about 15% of the outpatient mental health services that hospitals provide. It is projected that in 2021 mental health services in hospitals and outpatient hospital facilities will be paid in the same way as all other medical services.

Payments for Long-Term Care

Municipalities are responsible for paying for home-based and institutional (nursing home) long-term care. Municipalities own nursing homes and employ their workers. Special grants from the national government finance the construction of additional assisted-living facilities and nursing home beds.

There are substantial income-linked patient co-payments for home-based and nursing home custodial care. Importantly, there is no exemption or co-pay maximum for these services as there is for visits to GPs.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicines

In Norway public resources pay for some minimal complementary and alternative medical care, particularly acupuncture. But practitioners outside the public health care system offer the vast majority of these services, including homeopathy and naturopathy. These services are paid for by individual out-of-pocket payments without any reimbursement.

Payments for Preventive Services

Municipalities finance public health, school-based, and youth clinics that provide immunizations for children as well as health education on nutrition, exercise, contraception, and other matters. Municipalities set priorities for capital investments for these clinics and pay for them. GPs are also reimbursed for other preventive services, such as cancer screenings.

Out-of-Pocket Payments

Two “exemption card schemes” limit patients’ out-of-pocket payments. Patients who exceed the maximum out-of-pocket payments automatically receive an exemption card (frikort) for public health services. They are then not required to pay any additional out-of-pocket costs for the calendar year. Group 1 exemptions include co-pays for GP visits, outpatient hospital clinic visits, X-ray and laboratory services, patient travel, and blue list—outpatient retail pharmacy—drugs. Legislation establishes the maximum co-pay per year before no additional payment is required. In 2019, the maximum out-of-pocket payment was $280 USD (2,460 kr.) for Group 1. Group 2 exemptions include co-pays for physiotherapy, certain types of dental treatment, and admission to rehabilitation facilities. In 2019, the Group 2 limit was $242 USD (2,085 kr.).

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

The Norwegian system is consumer friendly in its simplicity, choice, and limited financial barriers. Since 2002 residents have had the right to choose a GP and switch GPs up to 2 times a year. Patients can go to any hospital in the country and receive fully subsidized care. There are low caps on out-of-pocket costs for physicians and drugs. But, unlike in Germany, GPs are effective gatekeepers for more specialized care. There are significant waiting lists for services, and specialized services often require extensive travel to more urban centers. Also, long-term care is costly.

Hospital Care

There are approximately 60 hospitals in Norway, with just over 13,000 beds, about 2.4 beds per 1,000 residents. The number of hospital beds has declined by 23% since 1990. This is a much lower number than in Germany (8.2 per 1,000 population) and about the same as in the United States (2.4 per 1,000 population). There are about 540,000 hospital discharges, or just over one discharge per 10 people, about a quarter of the number in Germany and the same as in the United States. Consequently, length of stay is comparatively short—about 4.1 days per admission—and bed occupancy rates are at about 90%.

Almost all the hospitals in Norway are public hospitals. Aside from public hospitals, there are 6 university hospitals, which have over 45% of all beds, and 8 private hospitals.

How do patients get hospital care? For serious acute problems, such as crushing chest pain or loss of consciousness, the local on-call service calls an ambulance to take the patient to the hospital. Once admitted to a hospital, the hospital-based physicians—not the patient’s personal GP—care for them. If the on-call services feel the problem is not that acute, they might send patients to a local urgent care or casualty center that operates 24/7. Physicians and nurses on staff then make an assessment.

In a nonemergency situation the patient sees their GP. If the GP believes the problem requires specialist care, the patient is referred to the hospital, where a specialist will administer care and, if necessary, admit the patient for medical or surgical care. Norwegian GPs thus act as gatekeepers to hospital services and hospital-based specialist care.

The hospital delivery system has several problems. One is that there are serious waiting times for elective procedures. Patients can see waiting times for a particular procedure at all hospitals in Norway and select hospitals based on wait times. For-profit hospitals do not provide acute care but rather are often contracted by RHAs to provide specialized elective procedures, such as cataract surgeries, to relieve these waiting times.

Another problem is the need for patients to travel for care. Norway is large but sparsely populated. It is only slightly smaller than California but has just 12% of California’s population. This creates challenges in providing hospital care to the rural population. Over the ast few years several new programs have been established to improve quality and efficiency. There has been a push to close or consolidate some rural hospitals, although local public resistance has often stymied efforts to close them. In addition, specialized care has been centralized into “centers of excellence.” For instance, percutaneous cardiac interventions are available at only 7 hospitals, 2 of which are in Oslo. Although this has increased standardization of care and quality, it has also required many Norwegians to travel great distances for specialized care and increased the need for air ambulances.

Specialist Care

Almost all specialist care is provided in hospital-based outpatient facilities. Specialist care thus falls under the RHAs’ authority. There are about 15,000 specialist physicians. Hospital-based specialists provide free advice to GPs on managing patients with particular medical problems. These physician-to-physician consultations can help GPs provide follow-up care after a specialist consultation. In practice, however, these specialist consultations tend to be haphazard and not standardized.

Norway also has “mobile” specialists who visit patients in their homes. They most frequently provide geriatric and palliative care for home-bound elderly patients.

Some specialist physicians, such as obstetricians, dermatologists, oncologists, and others, are self-employed and practice privately.

Primary Care

The GPs provide primary care services and serve as gatekeepers to specialist care. As part of their payment from the municipalities, GPs are also required to work for municipalities, including by providing after-hours on-call services and covering nursing homes. Their municipal services may include work in local health clinics or stations overseeing nurses that provide primary care services, such as postnatal newborn and maternal care, services for children up to school age, adult preventive services, and some mental health services.

Norway has about 4,800 GPs who provide office-based primary care. Most GPs in Norway work in small groups of 3 to 8 physicians, which include nurses, lab technicians, and a secretary. On average each GP has a patient panel—or patient “list,” as they are called in Norway—of just over 1,100 people, which is a comparatively low number of patients per physician. For instance, at Kaiser in the United States, physicians have an average patient panel of about 1,900 to 2,100 people.

The GPs’ offices offer limited office hours (8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.). Municipalities organize after-hours calls as well as nonhospital urgent care facilities. The municipalities require GPs to take after-hours call shifts on a rotating basis. In urban areas with relatively high numbers of GPs, the GP will do one on-call night about every 3 weeks.

Norwegians are not heavy users of physician services. On average Norwegians see GPs 2.7 times per year and visit the emergency departments only 0.25 times per year, a much lower rate than in Germany, France, and the United States.

Mental Health Care

As in most countries over the last 50 years, mental health care in Norway has undergone a shift from inpatient psychiatric hospitals to outpatient treatment. In 1998, the Parliament adopted the National Program for Mental Health, which made mental health a priority by requiring the municipalities to invest more financial resources and hire more trained personnel. Although there has been a decline in institutionalization, Norway still has a comparatively high number of psychiatric beds, about 4,000, 82 per 100,000 population.

As with all health care in Norway, mental health care is bifurcated. The first line of mental health care is the GP, who cares for patients with mild or moderate mental health conditions such as comorbid depression or anxiety. GPs can receive specialized training in cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, there are psychologists and psychiatric nurses at the municipal level to supplement GP mental health care. There are private-practice psychiatrists and psychologists. GPs can refer patients to private practitioners, and the public system often pays for these services.

Patients with moderate to severe mental health conditions get specialized care from District Psychiatric Outpatient Services (DPOS). DPOS provides outpatient services for chronic conditions such as eating disorders or bipolar disorders. DPOS care is hospital based and, thus, falls under RHA auspices. Finally, for the severely mentally ill there are 7 psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric wards within the larger hospitals. There are also private mental health hospitals that tend to care for patients with eating disorders as well as for geriatric psychiatric patients. Such private hospitals often provide services for patients—paid for by the RHAs—to relieve waiting lists.

All mental health care services have the same co-pays as GPs.

In 2004, substance abuse and alcohol treatment were deemed specialized mental health services and transferred to RHAs. Norway has a substance abuse problem, with over 17,000 patients currently being treated for substance abuse, and a high drug overdose death rate. Most such substance abuse patients get their care at specialized outpatient treatment units affiliated with hospitals. These specialized units can involve GPs in managing substance abuse.

Long-Term Care

About 15% of the Norwegian population is over 65. Municipalities are responsible for providing all long-term care services for the elderly and disabled, encompassing at-home care, adult day care centers, and nursing homes. Municipalities own the long-term care facilities, determine eligibility for services, and decide what combination of services to provide. The priority in municipalities is to keep people at home as long as possible, as this is far cheaper than moving them into nursing homes. Consequently over 100,000 Norwegian seniors receive personal or custodial care at home, about 45,000 receive care in nursing homes, and another 45,000 receive care in assisted-living facilities, also called sheltered housing.

These services require high co-pays. For instance, for nursing home care the first $760 USD (6,600 kr.) of income is excluded, but then patients pay 75% of income above that up to nearly $11,500 USD (100,000 kr.) and then 85% on all income above that level.

Preventive Care

Norwegians get preventive care services either from their GPs or the local, school-based, or youth health clinics.

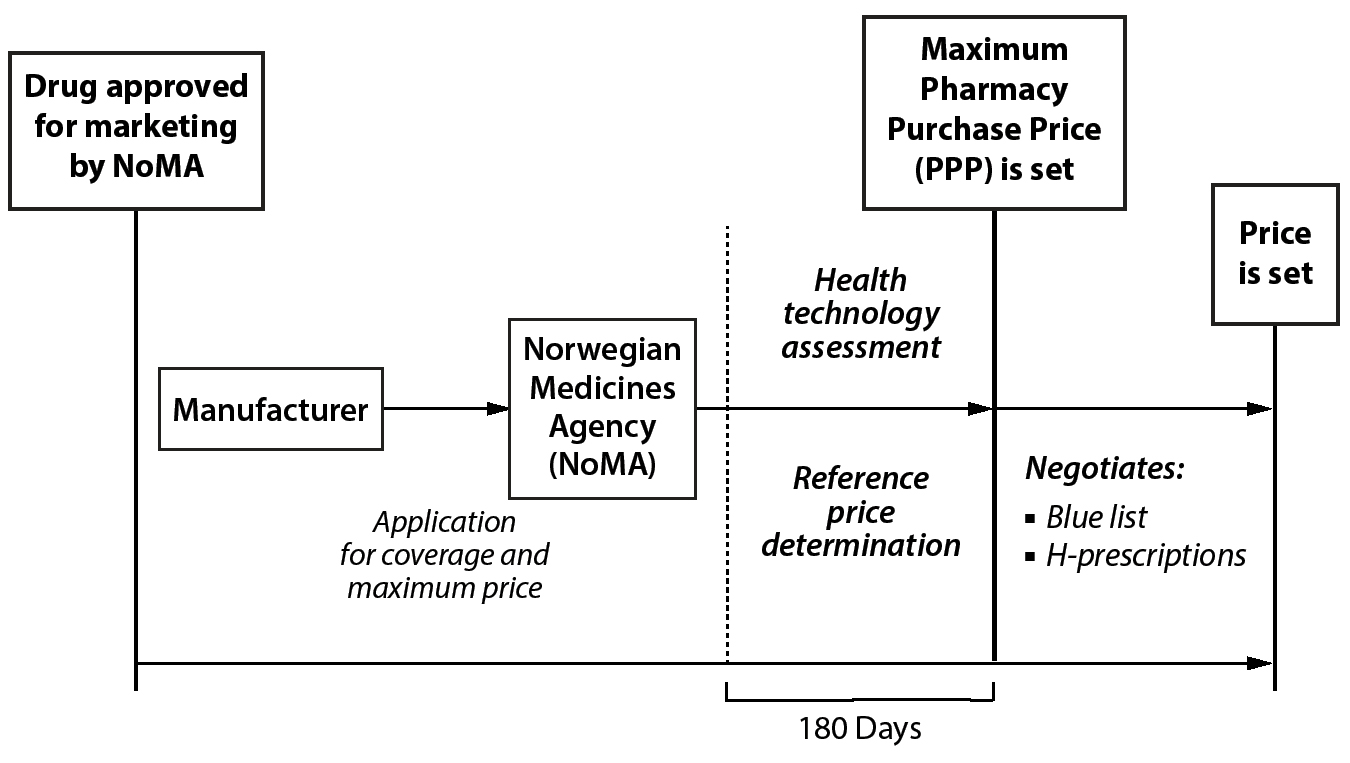

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (Norway)

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

The Norwegian market for pharmaceuticals is tiny, about $2.2 billion USD ($20 billion kr.). Overall less than 10% of national health care spending is devoted to drugs, amounting to just over $400 USD per capita. Norway has some of the lowest drug prices in Europe, and Norwegians consume a relatively low number of drugs per person, compared to other European countries. But, as in other countries, expensive drugs for cancer and rare diseases have pushed up total drug costs significantly. Public insurance bears about 75% of all pharmaceutical costs, while consumers pay about 25% out of pocket.

Coverage Determination

A branch of the national Ministry of Health and Care Services, the Norwegian Medicines Agency (Statens legemiddelverk [NoMA]), authorizes the marketing of drugs, monitors adverse events, and sets maximum prices. Its procedures for marketing approval are harmonized with European Union regulations. Marketing authorization is valid for 5 years. Although there is no cost-effectiveness requirement for marketing approval of a new drug, cost effectiveness is considered as part of the coverage decision.

After marketing approval, manufacturers must apply to NoMA for a maximum pharmacy purchase price, which constitutes a coverage and reimbursement decision. Because a drug cannot be marketed without a set price, the coverage and maximum pricing decisions are separate from the marketing decisions, even though the same agency is responsible for these different approvals.

As part of the coverage and pricing decisions for new prescription drugs, there must be a Health Technology Assessment (HTA). In 2013, Norway adopted what has been dubbed the New Methods to systematically evaluate new interventions in specialist care to ensure an orderly, equitable introduction of the approved technologies, including new prescription drugs. A major component of the New Methods system is the requirement for covered technologies to undergo an HTA, which informs decision making and price negotiations. In 2016, Parliament endorsed a report requiring new technologies—including prescription drugs, genetic tests, devices, surgical procedures, and other interventions—to be prioritized using 3 criteria: (1) overall benefit, (2) resource use, and (3) the severity of the condition. Since the publication of this report, the use of HTA has been extended to all new medicines, with the exception of Schedule 4 drugs for serious infections such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (described below).

The most common form of HTA for prescription drugs in Norway—including all outpatient drugs—is single technology assessments. NoMA conducts all the single technology assessments for prescription drugs. Single technology assessments compare a drug to the best standard of care. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health conducts the full HTAs of other prescription drugs—finding the best therapy among multiple interventions for a condition—and all HTAs of other medical technologies.

Whether NoMA should use a cost-effectiveness threshold is controversial. An informal threshold of about $31,500 USD (275,000 kr.) per QALY, which is similar to the threshold used by NICE in Britain and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia, seems to inform decisions. However, the suggested threshold is higher for more severe illnesses, up to $94,500 USD per QALY (825,000 kr.) for life-threatening conditions.

The use of HTAs in approving drugs (as well as other technologies) constitutes a systematic and transparent way of evaluating new medical services’ value.

LIKE EVERYTHING ELSE in the Norwegian health care system, the divide between primary and specialist care affects prescription drugs. The Directorate of Health within the Ministry of Health and Care Services makes a critical decision about whether the prescription drug is for primary or specialist care. This decision is triply important because it controls (1) how a drug’s price is determined, (2) what patient co-pays are, and (3) which government agency pays for the drug.

Norway has a list of covered drugs for primary care, called Schedule 2 drugs, or blue list drugs. Blue list drugs are out-of-hospital drugs for chronic conditions—requiring 3 or more months of treatment per year—that the NIS reimburses through HELFO. Patients have a co-pay of 39% for these drugs, with a maximum of $58 USD (520 kr.) per drug and which is part of the annual out-of-pocket maximum of $275 USD (2,369 kr.).

In some cases, drugs will be prescribed for indications that have not been approved on the blue list or for rare diseases—Schedule 3a and 3b drugs. Physicians must apply for reimbursement for each individual patient, and the NIS decides on each individual reimbursement. There are also Schedule 4 drugs, used for infections such as HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis. These drugs are fully paid for, and patients have no co-pays.

There are white list prescription drugs that are not covered, and thus patients must pay 100% of the cost. These white list drugs include short-term and/or discretionary medications such as short-term antibiotics, sleeping pills, and painkillers.

Then there are H-prescription drugs, which are specialty drugs that are used out of the hospital, such as drugs for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, asthma, and hepatitis B. The Directorate of Health decides which drugs are on the H-prescription list. Less than 1% of prescriptions are H-prescriptions, but they account for nearly 20% of drug costs. The number of H-prescriptions and their relative proportion of pharmaceutical costs have been increasing as more drugs are shifted from the blue list, such as drugs for hepatitis C. The 4 RHAs pay for the H-prescription drugs, and patients have no co-pays.

RHAs consider HTAs when determining coverage for both in-hospital and H-list drugs. The Commissioner Forum of New Methods, composed of members from the 4 RHAs and the Norwegian Directorate of Health, prioritizes the candidate topics and decides which assessments should be commissioned. The HTAs are eventually submitted to the Decision Forum of New Methods. Here the RHAs’ CEOs have the authority to decide about introducing the new medicines and other technologies in specialist care. Because the 4 RHAs decide together, the assessed interventions are introduced across the country simultaneously.

There is no national coverage determination or price regulation for over-the-counter drugs. Prices are set by pharmacies and patients pay for them out of pocket.

Price Regulation

For blue list drugs, NoMA defines maximum prices and reimbursement levels. NoMA also sets the maximum pharmacy purchase price for nonhospital drugs. After marketing approval, manufacturers must submit pharmacoeconomic data such as price, clinical benefits, therapeutic comparator(s), number of patients, and budgetary implications to NoMA. The new prescription drug then undergoes an HTA. Using this HTA, NoMA then makes a coverage decision. It then determines the maximum pharmacy purchase costs based on a reference price that is established by averaging the lowest 3 prices for the drug in 9 European countries—Austria, Belgium, Great Britain, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Sweden. If the drug is not sold in at least 3 of these countries, then NoMA uses the average price of the countries where it is sold.

Drugs cannot be sold at costs exceeding the maximum price, but they can be sold at any price below the maximum. Manufacturers may ask NoMA to reevaluate the maximum price if there are new data on European prices or clinical benefits.

For drugs covered by the NIS, there is also a total budget impact or affordability assessment. If the estimated annual incremental cost of the drug based on price and use exceeds $11.5 million USD (100 million kr.) for the whole country, the Ministry of Health and Care Services must review the drug. If it endorses the drug, the Parliament then needs to include its approval in a budget bill. Conversely, if the estimated cost is less than $11.5 million USD, then the Norwegian Medicines Agency (NoMA) decides on coverage of the drug.

There is a centralized procurement system for hospitals funded by the 4 RHAs, called the Hospital Purchases HF (Sykehusinnkjop HF). Through this system, price negotiations with drug wholesalers and manufacturers may be conducted to lower costs for hospitals.

In 2001, Norway began requiring generic substitution whenever possible. In 2005, Norway introduced stepped pricing to lower generic drug prices, thereby encouraging their use. In this model, after a patent expires, NoMA determines whether there is a suitable generic. If so, the price for the generic is lowered every 6 months. By 18 months after the generic is introduced, then, the price is lower than the brand-name maximum price by at least 90%. Pharmacies must inform patients if a cheaper generic alternative exists. If the patient refuses to switch to the generic, they will need to pay the difference in price between the 2 alternatives. Because profit margins on the generics are higher, pharmacies have a financial incentive to dispense generics. These policies have been successful, and generic drugs now constitute 70% of prescriptions.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

Reimbursement for drugs only occurs for approved indications, and physicians cannot prescribe drugs for unapproved indications. If they want to prescribe off label, they must apply for the drug to be given to a specific patient as a Schedule 3a.

Prices Paid by Patients

Patients have co-pays for out-of-hospital drugs. For blue list (Schedule 2) and Schedule 3 drugs, patients pay 39% of the cost, up to about $60 USD (520 kr.) per prescription. Payment for blue list drugs is included in the out-of-pocket maximum, which is about $275 USD (2,369 kr.) per year for a combination of services, including GP visits and X-rays. After they reach this out-of-pocket maximum, all prescription drugs are free. For children under 16, there is no co-pay for blue list drugs.

There are no patient co-pays for drugs prescribed during a hospital admission, H-prescriptions, and Schedule 4 drugs. For white list drugs, patients pay the full amount, up to $200 USD (1775 kr.) per year.

Norwegian pharmacy markups are strictly regulated. Pharmacies get 2 markups on blue list medications. One is a percentage added to the pharmacies’ purchase price (2.25%), and the other is a fixed amount ($3.30 USD [29 kr.]) per package. In addition, all pharmacy prescriptions are subject to the 25% Norwegian value-added tax.

The Pharmacy Act of 2001 deregulated ownership to increase the number of pharmacies, resulting in an increase of about 25% since 2011, and to generate more competition. By law there is no direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs, but companies may advertise over-the-counter drugs on TV and online.

Other

Recently Norway began pilot programs that pay pharmacies to train patients to use inhalers for asthma and to educate them when starting blood pressure and cholesterol-lowering medications. The goal of these programs is to improve medication compliance for patients with chronic conditions.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

Norway has over 26,000 physicians, or just over 5 per 1,000 population—the highest rate in all Nordic countries. Compared to all other Nordic countries, Norway has had the greatest growth—more than triple—in the number of physicians since 1980.

Of all physicians, approximately 4,800 (20%) are GPs, with about 60% of GPs practicing as specialists, which requires 5 years of training beyond an internship. Overall about 40% of GPs are women. Between 15% and 20% of Norwegian GPs are foreign born or have foreign citizenship. More importantly, nearly 40% of GPs were trained outside Norway, with the largest group trained in Poland. Over 90% of GPs are in group practice; they have relatively small panel sizes—just over 1,100 patients per GP.

There are over 15,000 specialists in Norway—over 3 times the number of GPs. Almost all are employed by hospitals, and there are 46 different recognized specialties.

Norway has a geographic maldistribution of physicians. About 20% of the population lives in rural areas, and this percentage has been slowly declining. According to the OECD, there are nearly twice as many physicians in urban areas as there are in rural ones—7 per 1,000 population versus 3.8 per 1,000 population. Like other countries with substantial rural populations, Norway has tried a number of programs to attract physicians to rural areas. In 1973, Norway opened a medical school in the far north’s major city, Tromsø. Although the medical school induced more physicians to practice in northern Norway, they mainly stayed in more urban areas, like Tromsø, and are affiliated with the university hospitals.

Compared to those in many other European countries, Norwegian physicians’ salaries are low. However, compared to other Nordic countries, Norwegian salaries tend to be high. According to Statistics Norway, the government statistical agency, GPs make an average of $92,000 USD (800,000 kr.) per year. Specialists, including surgical specialists, make an average of $110,000 USD (957,000 kr.) per year. The average Norwegian makes around $42,000 USD (365,000 kr.) per year.

Norway has 4 medical schools that together enroll a total of 600 students per year. Medical education is free, paid for by the national government. Norway even pays for students to study medicine in foreign universities. In Norway medical school takes 6 years, followed by 1.5 years of an internship and 5 to 6.5 years of specialization training. About two-thirds of all medical students are female, indicating that the profession will soon become predominantly female.

Nurses

Norway has about 103,000 nurses. This is the 2nd-highest number of nurses per population: over 17 per 1,000 population and about 3.5 nurses per practicing physician. Despite these high numbers, Statistics Norway predicts a shortage of 28,000 nurses by 2035. Many nurses in Norway are recruited from other European countries.

Nurses’ salaries are comparatively high. According to Statistics Norway, full-time nurses earn on average about $67,000 USD annually (over 576,000 kr.). There is relatively high nurse job satisfaction, with few wanting to leave the profession or not recommending it.

Although there are some specialties, such as nurse anesthetists and geriatric nurses, the nurse practitioner position is at the earliest stages. To date, Norwegian nurses are not permitted to write prescriptions or order tests.

CHALLENGES

The Norwegian system has many strengths.

It is absolutely universal based on paying taxes. There is no access barrier, such as enrollment in an insurance plan or paying a premium. Patient choice is real and extensive. Patients can choose any GP, may change their GP twice a year, and have minimal co-pays. They can go to any hospital in the country for care and have no co-pays. And all medical, dental, and vision care services for children are free. Physicians have low panel sizes and manageable work hours. Although there is some controversy about whether the latest drugs are somewhat delayed in their introduction to the Norwegian market, the country has the latest technology and all drugs. Norway has taken high costs and resource allocation issues seriously, establishing the New Methods to create a systematic process for conducting health technology assessments and integrating them into coverage decisions for drugs and other technologies. Finally, of all the systems I surveyed, Norway’s seems the least complicated and easiest to navigate.

Nonetheless, there are 6 serious challenges, with each tracing back to some dimension of the system’s structure. The first 2 challenges relate to different aspects of care coordination. First, the rigid distinction between GPs and hospital-based specialist care—as well as the different ways they are paid, incentivized, and held accountable—fosters poor coordination between primary care and specialized, hospital-based care. Municipalities largely finance and oversee GPs and home care, but specialty care is organized by separate RHAs that are operated regionally, not locally. This makes it hard to get patients optimal care. As one academic health policy expert stated, “There is no dialogue between GPs and specialists. GPs refer patients. Specialists accept the referral, and the patients return to their GP. Information back from the specialists to the GPs is haphazard at best.”

The multiple sites of care for patients with complex illnesses exacerbates this poor coordination. For instance, a patient with cancer might get surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy at 3 different facilities in 3 different locations as well as have a GP in a 4th community. This dispersion of care can ensure high-quality services at each step, but there are transition challenges and barriers to coordinated care. Much of this coordination can be facilitated because Norway is small and people know each other. Even the biggest cities are small—Oslo has only 630,000 people and Bergen has just over 250,000. But care coordination that relies on informal networks will be haphazard and frequently fail—often for the patients who need it most. Indeed, as one health policy expert put it, “A Norwegian needs to be quite healthy to become sick, because there are a lot of things to organize and it is hard to line everything up. GPs are supposed to coordinate care, but they don’t.” Efforts to incentivize more coordination—such as requiring municipalities to pay for patients ready to discharge from hospitals without available outpatient services—have failed to solve the problem. Adequately addressing the problem requires clinical, financial, and administrative alignment of GPs, specialists, and hospitals. The rigid divide between the primary and specialist care systems, however, complicates such alignment.

Second, and relatedly, the care coordination infrastructure necessary for optimal management of patients with chronic disease is lacking. Like all other health systems in developed countries, Norway’s evolved in the 20th century to address acute medical conditions. But the predominant medical issues of the 21st century are multiple chronic conditions that cannot be solved by episodic visits to the GP or hospital. Optimal chronic care requires a lot, including:

• extended office hours;

• after-hours care by someone who knows the patient or at least has access to their medical record;

• open-access scheduling so physicians can see patients in their offices instead of sending them to urgent care or emergency rooms; and

• chronic care coordinators who work in GP offices and proactively engage with and educate patients daily or weekly to ensure compliance with medications and other medical interventions.

The problem, as one expert stated, is that “geriatric care for patients with chronic conditions is not well coordinated. It is not prioritized by the health care system. And there is little integration of social services and medical services.” Although Norway has excellent community health clinics, even as they are good at delivering immunizations, preventive services, and postnatal care for mothers and children, they are not optimal for coordinated chronic care for elderly patients. A well-developed system of home-based nursing care may partially compensate for this.

In addition, GPs have little incentive to redesign how they provide care. GPs are paid by capitation and on a fee-for-service basis, neither of which provide any financial incentive to reduce hospital admissions. GPs get a fee for medication reconciliation and coordinating care, although that fee is low, does not incentivize comprehensive care, and is too low to incentivize care redesign. And GPs have no responsibility, accountability, or incentive to limit the total costs to the system of patients’ care. GPs also receive no feedback on the quality of their care or pay adjustment based on quality or excessive hospital admissions. Paying pharmacists to educate patients who are initiating chronic medications, such as for high blood pressure or cholesterol, is good, but it hardly ensures medication adherence and does not constitute coordinated care. Providing more chronic care coordination would require municipalities to make significant changes in terms of how they pay and incentivize GPs, quality reporting and feedback, and after-hours care. It is unclear whether municipalities have the human and financial resources to do this.

A 3rd challenge is waiting times. The caricature of socialized medical systems is that patients must wait and wait for care services. Although this is exaggerated in many ways—including the fact that waiting times are also long in nonsocialized medical systems—Norway has a serious waiting time problem. This is indicated by the recent growth in supplemental private insurance, the main purpose of which is to circumvent waiting times.

Part of the problem may be an attitude among health care experts that a waiting time can be useful. For instance, some Norwegian experts thought that patients with back pain on a waiting list for surgery may find that their pain stops on its own, eliminating the need for surgery. And some hospital administrators may manipulate waiting lists to increase their leverage in budget negotiations. There have been multiple efforts to address the problem, including publicly listing hospital waiting times for various procedures at different hospitals and allowing patients to select hospitals based on waiting times. Another partial solution has been for the RHAs to pay private hospitals and practitioners to perform elective procedures. The problem persists, though, and Norwegians feel annoyed and are losing confidence in the system.

The previous problems relate to a 4th challenge: the system is not patient centered, although some elements are focused on how patients will use the services. For instance, the location and operation of community, school, and, especially, youth clinics seem attuned to particular patient populations’ needs. But in general, the system is still physician centric. Physician office hours are limited, and few use open-access scheduling. Pharmacy times have also been limited. After-hours care is performed by rotating physicians who often have no detailed information about the patient. Home care is limited, and to see a specialist or get imaging or laboratory tests, patients must travel to one of the major hospitals because there are few community-based specialists. This can work for acute, one-off problems but not for chronic conditions.

Some efforts are being made to solicit patients’ experiences and make the system more responsive. For instance, the RHAs have patient ombudsmen, all hospitals are required to have patient boards, and there are patient experience surveys. But these efforts are only the first steps in creating a patient-centered system.

A 5th challenge is quality. In general, Norway provides high-quality care, but the quality data that the system collects is not integral to operations and payment. The Directorate of Health in the Ministry of Health and Care Services collects quality data on hospital infections, survival rates for various conditions, waiting times, and related data. Unfortunately, as one official in the Directorate of Health said, “Not even results from the best registries are used to follow up patients or to routinely monitor and improve quality.”

Relatedly, many Norwegian health policy experts worry that there is a great deal of wasted, unnecessary, and inefficiently delivered care. Quality payments affect less than 1% of hospital payments. Although waiting times are publicly available, other quality data, such as about physician performance, are not. For instance, data on ensuring that people with diabetes have their blood glucose, blood pressure, and lipids under control is not collected or disseminated to physicians or the public. Similarly, quality and waste data related to the frequency of ER visits and hospital admissions for patients undergoing chemotherapy or with diabetes or other chronic conditions are not routinely assessed or given back to physicians with comparisons to other practitioners. The Minister of Health and Care Services has urged the RHAs and hospitals to reduce unnecessary care. Quality data to inform patients which GPs are high performers are not available, nor are data used for bonuses or to modify capitation or fee-for-service payments to GPs.

Finally, some key services are not well integrated into the system. That dental and vision care for adults are paid 100% out of pocket seems outdated. More importantly, Norway does not seem well positioned regarding long-term care. There is no national long-term care insurance; municipalities are responsible for funding both home-based and institutional long-term care. One consequence of this is that elderly Norwegians pay for a substantial portion of long-term care services, which consumes most of their pensions and other resources. This may be a wise policy choice when combined with free care for children, but it means that long-term care is more unequally distributed. Over the last few years there was significant investment in building thousands of nursing home beds. But as the senior population grows—thus increasing the needs for more custodial and nursing services—the system will need to expand in-home and nursing home care. Municipalities might not be able to afford and organize such care. Inadvertently this may lead to increased use of hospital services if outpatient services are unavailable. Although policymakers are aware of this problem, solving it is another issue.

All of these challenges, though, are at the margins of a system that is easy to use and generally works well: it is universal, provides extensive choice, has no co-pays for children and limited co-pays for adults, and may be the least complicated system in any developed country.