CHAPTER FIVE

FRANCE

“Every country’s health care system is driven by a core national value. For the United Kingdom, it’s utility. For Germany, responsibility. For the United States, liberty. [And for France,] equality,” says Dr. Laurent Degos, vice president of the Pasteur Institute.

As Dr. Isabelle Durand-Zaleski has said, the French system truly is a “chimera.” It combines a wide but shallow compulsory public health insurance with practically essential supplemental private insurance to cover high out-of-pocket costs. Simultaneously, it merges largely centralized financing and strong national regulation with privatization in its delivery systems.

The French love their freedom to choose any private physician and among many private hospitals, and they can go to any specialist without primary care gatekeeping or a referral. But this cherished freedom of choice creates what is probably the biggest challenge of the French system: extreme fragmentation of care. As one patient reported, whenever he goes to his physician he makes sure to bring his own X-rays and other test results; otherwise the consulting physician will not be able to access them. At a time when most of health care is focused on chronic conditions, this fragmentation of care raises the question of whether the French system lives up to its esteemed reputation for equal, accessible, and high-quality care for all.

HISTORY

France adopted a national health care system relatively late. Whereas Germany enacted its employer-based Bismarckian system during the 1880s, France did not pass its first form of national health insurance until 1928. Prior to this, medical care was largely accessible only through sporadic employer benefits, fraternal associations, and direct fee-for-service purchases.

This original national health insurance was narrow in scope. It only covered low-wage salaried workers in industry or commerce. It excluded their families, moderate- and high-wage workers, farmers, the self-employed, students, and the unemployed. It reimbursed physicians exclusively fee-for-service and offered limited benefits. It did expand over time, however, so that by the end of the 1930s it covered roughly two-thirds of the French population.

World War II decimated French society and displaced many entrenched institutions and interests. Many medical leaders were killed during the Nazi occupation, while others were delegitimized by their collaboration. In particular, mutual funds—the equivalent of German sickness funds—were maligned for their collaboration with the Vichy state. French physicians, however, kept their respected place in society. They famously defied the Nazis and continued to treat all wounded persons—both French and German—in accordance with their oaths.

In the postwar period, the French looked to rebuild and, under Pierre LaRoque’s guidance, crafted their first modern system of social security. As part of this, they sought to improve national strength by expanding health insurance to all workers and their families, irrespective of their income. Mutual funds had been providing these services but were shunted aside as the primary vehicle for coverage and were forced to reposition themselves by offering supplemental insurance on a voluntary basis for services not covered by the mandatory national plan.

Despite significant pressure to move toward socialized medicine, physician groups kept their financial independence. Under the new, postwar system, French physicians were granted much of the professional autonomy they desired. They preserved private practice with fee-for-service reimbursement as the cornerstone of French health care. France eventually adopted a uniform fee schedule, but it took years of debate, culminating with Charles de Gaulle himself quipping “I saved France on a colonel’s pay” after physicians kept arguing for higher wages.

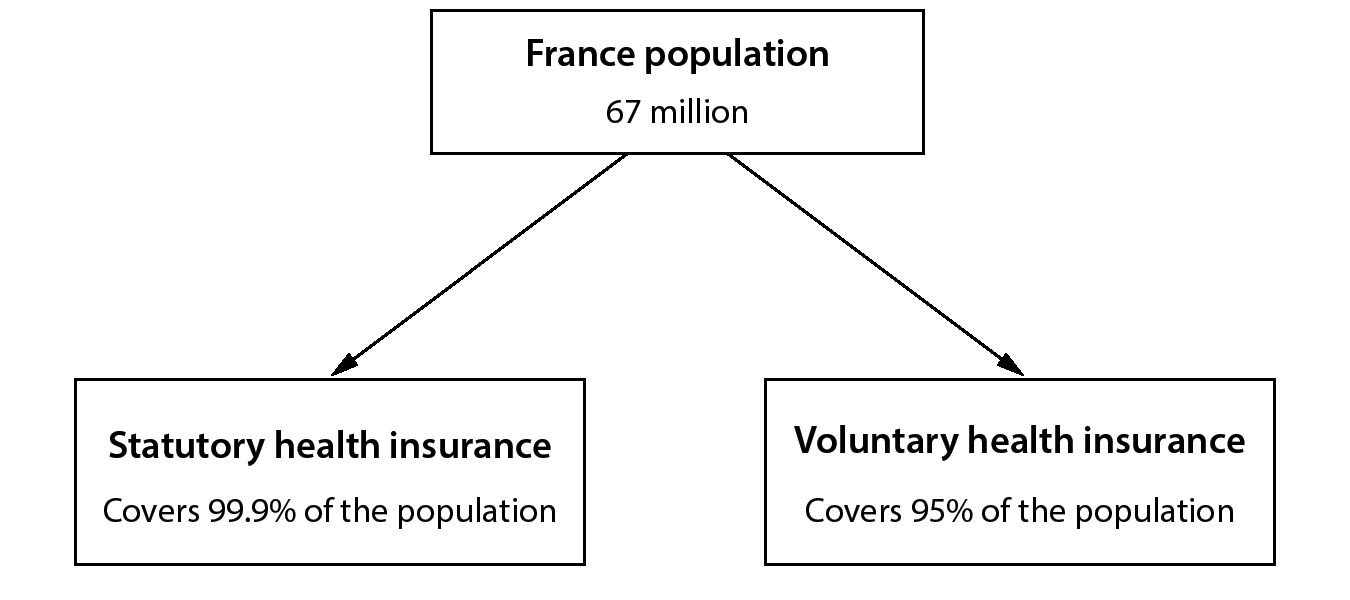

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (France)

Over the next 50 years, this national health care program underwent piecemeal expansion. In 1961, agricultural workers were included, and in 1966 the self-employed were brought in as well. But it was only in 2000, with the passage of the Universal Health Coverage Act (CMU), that universal coverage was officially achieved. The Universal Disease Protection Act’s (PUMA) passage in 2016 finally granted automatic and continuous eligibility to the national health insurance for all legal residents.

COVERAGE

The French health care system has 2 layers of coverage: mandatory basic health insurance provided by the national government and voluntary, albeit nearly universal, supplemental health insurance provided by private insurers.

Public, Statutory Health Insurance

The entire French population is covered by national statutory health insurance (SHI). Like the German sickness funds, the French statutory health insurance is not a single-payer system; instead, patients are covered through one of a handful of health care funds. However, unlike the German sickness funds, the French are assigned to their health care fund based on employment status. The French cannot “shop” between funds. The largest of these funds—the National Health Insurance Fund for Salaried Workers (CNAMTS), or the General Fund—covers nearly 90% of the population, including most salaried workers and their families. Two other funds, Mutualité Sociale Agricole (MSA) covering agricultural workers and Regime Social des Indépendants (RSI) for the self-employed, cover about 8% of the remaining population. The remainder is covered through a handful of smaller funds—largely historic—for specific populations such as miners, railway workers, and clergymen, among others.

Because benefits are nationally mandated and patients are assigned to funds based strictly on employment, the differences between the funds is minimal. They all cover the same basic package, and they all reimburse at the same rate.

In general the SHI benefits are quite broad and include inpatient care, outpatient services, prescription medications, medical goods, long-term care, and health-related transportation costs. Coverage is more limited for preventive services. And like many other countries, dental and vision coverage are, in the words of one physician, “nominal.”

Though broad, coverage under SHI is not deep, placing substantial out-of-pocket costs on patients. Coinsurance rates tend to be quite high with SHI alone. Inpatient care is generally covered at 80%, leaving 20% of hospital bills to patients. Similarly, in the outpatient setting 60% of laboratory tests are paid for by SHI while 70% of physician services are. Although patients are free to choose any physician, SHI will only cover 30% of specialist fees without a referral. Pharmaceutical reimbursement averages around 65%, but it varies from 15% for low-therapeutic products to 100% for nonsubstitutable and/or expensive medications. Thus, patients have substantial costs if they are only insured by the SHI.

SHI has also introduced small co-payments to raise revenues and reduce consumption. In 2005, a $1.08 USD (€1) deductible (participation forfaitaire) was introduced for every physician visit, laboratory test, and imaging procedure. In 2008, a 54 cent USD (€0.5) deductible was added for each prescription medication. These deductibles are capped: the maximum is $54 USD (€50) per year for medications and $54 USD (€50) for consultations. Importantly, there is no overall spending cap for out-of-pocket payments.

Most specialists and some general practitioners are also legally permitted to charge extra, beyond the official SHI payment. Such “balance billing” is not covered under SHI. As of 2018, these rates ranged from slightly higher than the nominal reimbursement rate to over 10 times the official SHI rate for certain specialists and specialties. While the 2015 Health Reform Law attempted to curb these excesses by containing an agreement for “responsible contracts,” balance billing remains a hotly debated issue in France.

Private Supplemental Insurance

Because of this high degree of cost sharing and out-of-pocket costs with the statutory health insurance alone, 95% of the French population has purchased private, supplemental voluntary health insurance (VHI). While only a handful of mandated health care funds deliver SHI, the voluntary health insurance is different. Myriad private insurance companies compete in an open market. Most of these plans are offered as part of an employment package, although individual plans are available. For the poorest parts of the population VHI is provided free of charge.

These plans largely serve 2 purposes. First, they reduce the degree of cost sharing for standard benefits covered under the national plan by covering coinsurance and certain amounts of balance billing. These plans thus function similarly to older Medigap plans in the United States. Second, they cover select benefits that the SHI does not cover. Almost all these voluntary plans cover dental and vision care, and many cover a wide range of additional services, such as complementary and alternative medicine. Unlike in other countries, French VHI is not used to increase access to desired providers or to avoid waiting times.

As VHI has historically been available only to the wealthy, recent legislation has aimed to increase access for all French citizens. In 2004, a new voucher system gave a “health check” (cheque santé) to everyone with income between 100% and 135% of the poverty line. These annual vouchers range from $108 to $615 USD (€100 to €550), depending on age, and they must be used to purchase private health insurance. Tax rebates encourage employers to provide VHI benefits to their employees. Since 2016, the government has required many employers to offer VHI. For individuals who cannot afford VHI by themselves or do not receive it through their work, the government offers its own state-sponsored VHI to around 10% of the population.

In this way, the French value of equality has caused the private voluntary coverage to become nearly universal. It remains an ongoing debate whether it would be better if the SHI simply expanded what it covers. Proponents argue that it could reduce the significant administrative costs associated with the VHI, while opponents are concerned this would disrupt the current system.

Special Coverage for Chronic Illnesses

The French approach seniors and the chronically ill by assuming complete financial responsibility for their medical care through the Chronic Disease (Affection de Longue Durée, or ALD) program. Each year the Ministry of Health defines 30 such categories of illness—including diabetes, asthma/COPD, heart failure, stroke, cancer, and long-term psychiatric disease. Patients who suffer from any of these afflictions are exempt from all costs related to the treatment of their illnesses, except for balance billing (if applicable) and the $1.08 USD (€1) participation forfaitaire. However, they are still responsible for paying for treatment for concurrent, nonchronic illnesses, such as an injury unrelated to their chronic condition. For patients with low incomes, most co-payments and coinsurance are waived.

FINANCING

Overall, France spends 11.5% of its GDP on health care, or $4,600 USD per capita. But it represents the 3rd-highest share of GDP in Europe, 2nd only to Switzerland and Germany. Around 80% of total healthcare spending is covered by statutory health insurance, 15% by voluntary health insurance, and 5% by out of pocket costs.

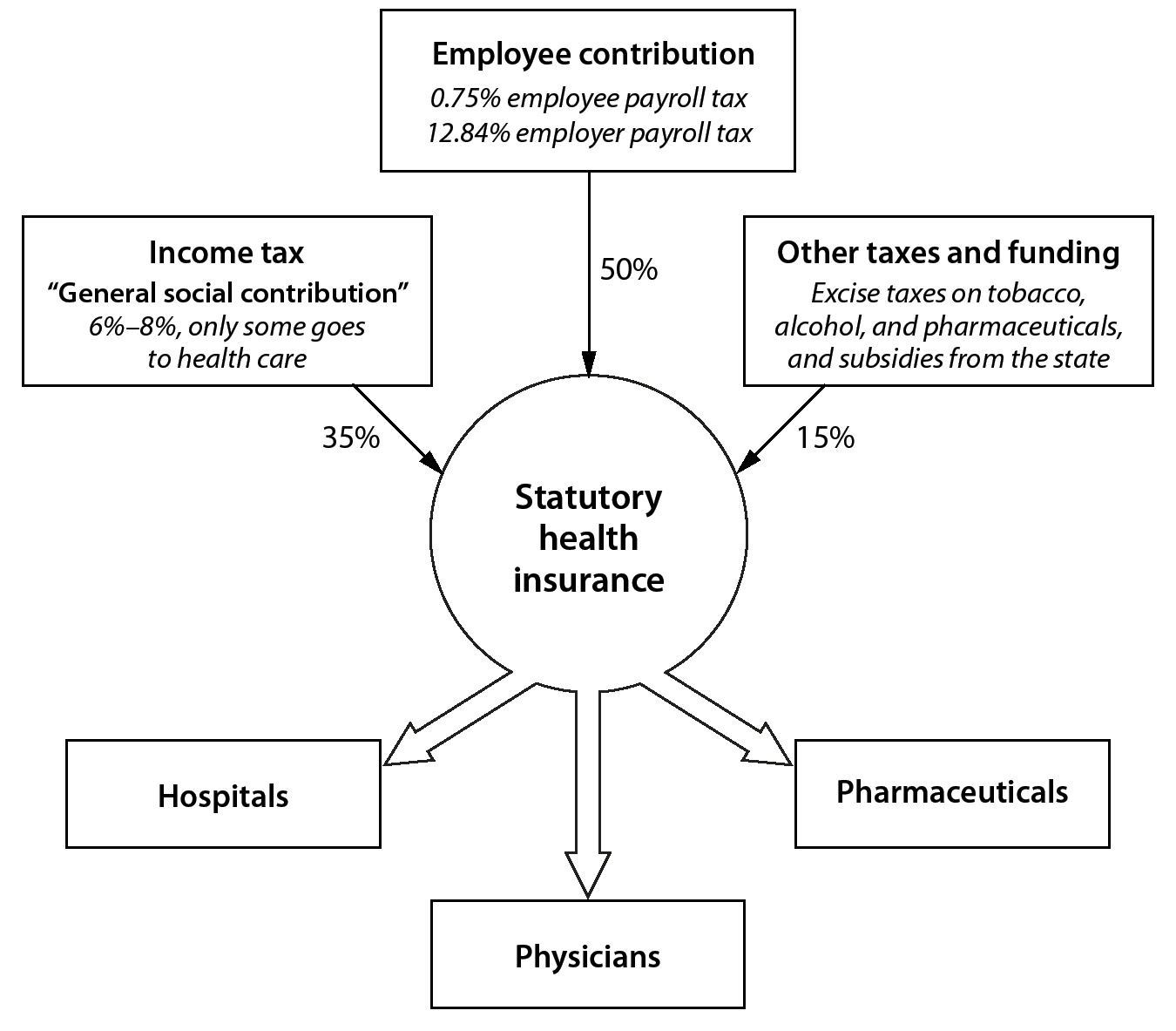

Statutory Health Insurance (SHI)

SHI has 4 funding sources: (1) a highly progressive system of payroll taxes (50%), (2) national income taxes (35%), (3) excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceuticals, and automobiles (13%), and (4) subsidies from the state (2%).

Figure 2. Financing Health Care: Statutory Health Insurance (France)

These funds are based on which industry each person works in, not by geographic location. In 2016, the payroll tax rate was 0.75% for employees and 12.84% for employers. The national income tax is known as the General Social Contribution (CSG). Its rate is based on the source of income. For instance, the CSG rate is 6.6% of pension income, 7.5% of earned income, 8.2% of capital gains, and 8.2% for gambling winnings. Only a fraction of the CSG goes to health insurance.

Voluntary Health Insurance (VHI)

A diverse market of largely private organizations funded through premiums provides VHI. Cumulatively, VHI accounts for about 13% of total health care spending. Most private insurance plans are obtained through an employer. Most private insurance funds use income-linked premiums and limited-risk rating. These organizations can consider age, health status, and region. Although age and region are commonly used, health status is rarely used in practice to establish premiums. Monthly premiums vary widely, from as low as around $16 USD (€15) per month for scant coverage to over $108 USD (€100) per month for generous coverage. For a 55-year-old couple, the annual premium can be about $2,700 USD (€2,500).

Long-Term Care

Long-term care in France accounts for over $50 billion USD (€45 billion) in spending each year. It is financed through 3 major sources: (1) health insurance, (2) social benefit programs, and (3) out-of-pocket costs.

Long-term medical care for seniors is covered directly though SHI and VHI. SHI covers nursing care and inpatient end-of-life services at the standard rates of coinsurance, unless exempted as an ALD program.

A meshwork of national and local programs covers custodial long-term care services, including housing payments for residential care facilities and certain home care services. The largest of these programs, the Personalized Allowance for Autonomy, is funded through a solidarity contribution all working citizens pay (equal to one unpaid working day). To increase revenues, an additional 0.3% excise tax was introduced on all retirement and disability plans. Smaller benefits are covered through a variety of other directed national and local taxes.

Finally, patients and their families bear a large—and increasing—proportion of long-term care. Despite the generous social and medical benefits offered through France’s system of social security, rising costs for long-term housing and insufficient levels of funding have left patients and their families to fill in the gaps. One study estimated that around 18% of supportive services, 81% of room and board, and 5% of health care services related to long-term care are paid for by families out of pocket.

Public Health

Historically, with the exception of maternity care, the French have lagged behind other nations in their embrace of public health measures and preventive medicine. On the individual level preventive services such as cancer screenings and vaccinations are largely covered by SHI, although co-payments exist for some preventive measures. To combat low rates of vaccinations, vaccination for 11 diseases is now free—and obligatory—for all children. Since 2017, a special incentive has been offered to general practitioners to advise adolescents and young adults on the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases.

On the systems level, general taxation pays for funding for public health offices responsible for tasks such as disease surveillance and national campaigns.

PAYMENT

Since 2004, payments for inpatient hospital stays have been based on DRGs. For the past century payments for physician services have remained largely fee-for-service. Recently, however, there has been a push toward pay-for-performance and capitated payments for French generalists, and these now account for approximately 10% of their reimbursement.

Payments to Hospitals

As of 2016, 73% of total hospital financing comes from DRG payments, while 27% comes from other sources, including annual payments and directed funding.

The Ministry of Health sets the DRGs and reimburses acute inpatient stays. These are referred to as the Homogeneous Group of the Sick (Groupe Homogène des Malades, or GHM). They were first introduced in 1986, and by 2004 there were 600 groups. As of 2009, there were over 2,300, each with 4 levels of severity.

Each year the Ministry of Health sets the rate of reimbursement for each GHM. Annually the Ministry of Health conducts a comprehensive bottom-up cost study that compares the most recent official French reimbursement with the real-world unit cost from about 16% of French hospitals. This is called the National Cost Studies with Common Methodology (Études Nationales de Coûts à Méthodologie Commune, or ENCC). The Ministry of Health then uses these data in the context of the overall budget established by Parliament and public health priorities to set the official French reimbursement levels, or tariffs, for the next year. Although this database is well done, the process has been criticized for a lack of transparency and public debate. It has also been criticized for its significant pricing inertia, in which prices for overvalued procedures are slow to come down.

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (France)

Interestingly, payments are different in both amount and what is covered between public and private hospitals. To start, DRG reimbursement levels (tariffs) for private, for-profit hospitals do not include physician fees, while tariffs for nonprofit hospitals do. Moreover, certain imaging procedures are included in the DRG for public hospitals but not for private hospitals. Imaging performed by private hospitals outside DRGs is paid at a negotiated fee-for-services.

Emergency room visits are also handled differently. This stems from private hospitals being tasked with negotiating their own contracts with the government. They have engaged in favorable patient selection and also tend to assume fewer research and teaching responsibilities.

In addition to DRG-based payments, hospitals also receive direct activity-based payments for emergency room visits and experimental or novel procedures as well as block grants to promote activities of national importance, such as public health measures, clinical research, and cost-effectiveness research.

Figure 4. Payment to Ambulatory Physicians (France)

*Convention 1 accepts fee schedule without balance billing; Convention 2 accepts fee schedule and balance bills; Convention 3 only accepts VHI and out-of-pocket expenses

There are limited efforts to penalize hospitals for poor quality or for high readmissions.

Payments to Ambulatory or Office-Based Physicians

About 85% to 90% of payments to French physicians are based on a fee-for-service model. This includes psychiatric physicians, who receive fee-for-service payments from statutory health insurance, as well as nonphysician providers such as psychologists, who receive fee-for-service payments from either voluntary health insurance or directly from patients. A small amount of payments are based on alternative payment models.

Every 5 years representatives from each professional society meet with the Ministry of Health and National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM) to negotiate a contract, known as a convention. These conventions set the standards and rates for various procedures and interventions. Between conventions there are annual amendments via the annual Social Security Finance Act.

On average for general practitioners 87% of their income comes from fee-for-service payments for clinical services (80%) and procedures (7%). Patient payment for balance billing represented less than 3% of their income. The remaining 13% came in the form of alternative payments models, including pay-for-performance and capitation models. Since 2007 this percentage of alternative payments has more than doubled.

Generalists have several reimbursement options to choose from. First, they may opt to stick with traditional fee-for-service payments and receive $27 USD (€25) per office visit. Alternatively, if they practice in a medically underserved region, they can opt to accept a guaranteed income of $7,700 USD (€6,900) per month. If they are publicly employed, they can also be paid a salary largely according to seniority. In addition, generalists can qualify for performance payments of up to $5,600 USD (€5,000) per year for adopting meaningful use of electronic medical records and doing well on quality metrics, such as immunizations and compliance with chronic disease guidelines. They can also receive an additional $45 USD (€40) per patient by participating in programs designed to help manage patients with chronic illnesses.

Almost all payments to specialists and surgeons are traditional fees-for-service payments. In contrast to generalists, 16% of specialist total compensation stemmed from balance billing and only 0.5% from alternative payment models. Since 2006, the share of procedural fees and the amounts of balance billing have risen.

The amount and type of balance billing depend on the sector in which specialist physicians choose to practice. Sector 1 physicians (conventionnés) have completely accepted the fee schedule from the every-5-year meeting. They must assume the standard reimbursement rate and are not allowed to charge any additional fees. In exchange, the national health insurance reimburses all fees, and the Sector 1 physicians receive a credit toward their social security contributions via a 2% reduction in their retirement contribution rate. Over 91% of generalists and 55% of specialists practice in Sector 1.

Sector 2 physicians are permitted to charge higher rates than those set by the meeting, but they must do so with “tact and measure.” SHI will still reimburse the standard rate, but patients are required to pay the difference between what the physician charges and the SHI fee. In exchange, these physicians relinquish several of the social and financial advantages granted to Sector 1 physicians, notably the reduced social security contribution. Providers must apply to become a Sector 2 physician, as the area is tightly regulated and the majority of Sector 2 physicians are required to concurrently have a full-time public hospital position. In total, 45% of specialists practice in Sector 2, while only 8% of generalists do.

Finally, Sector 3 physicians have completely rejected the negotiated fees and can charge whatever price they want. As a consequence, they are not eligible for any reimbursement through SHI. Only 1.2% of generalists and 0.4% of specialists practice in Sector 3. In general these physicians run boutique practices limited to the most affluent regions in France, such as Paris.

Nonphysician practitioners, such as nurses, pharmacists, and therapists, negotiate similar contracts with the Ministry of Health every 5 years and continue to be reimbursed through fee-for-service or salaried models.

Payments for Mental Health Care

The DRG activity-based payment model has not been extended to acute psychiatric hospitals. In public and nonprofit hospitals payment for mental health is by an annual prospective global budget. This budget is paid by SHI and allocated by regional health agencies on the basis of historical costs adjusted by the expected annual growth rate of hospital spending. Payments to for-profit hospitals are based on predetermined daily rates fixed according to the type of care provided, such as full-time or part-time hospitalization.

Payments for Long-Term Care

All citizens are automatically covered for medical benefits for long-term care through SHI and VHI. For custodial and residential services citizens must generally apply and demonstrate need. The largest national program, the National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy (CNSA), provides a Personalized Allowance for Autonomy (APA) to all citizens aged 60 and above who cannot perform daily activities independently. The monthly payment is based on the severity of disability and can be up to $1,900 USD (€1750) per month. Although it is not means tested, this benefit is discounted so that people with higher incomes can only earn 20% of the maximum benefit. There are various other benefits and tax incentives aimed at reducing the financial burden of long-term care.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Unlike many other countries, complementary and alternative medicine in France enjoys widespread health insurance coverage. SHI covers acupuncture, reimbursing it at half the cost of a general practitioner visit. SHI covers homeopathic products at a rate of 30% unless the products make certain health claims or contain high concentrations of medically active ingredients. VHI plans commonly contain additional coverage. Other forms of alternative medicine, such as osteopathy, are generally only covered by VHI or out-of-pocket spending.

Preventive Medicine

Most immunizations and recommended screening tests are paid for via SHI without coinsurance. The majority of preventive care, however, is not incentivized directly, and standard coinsurance rates apply for preventive care. However, there have been some recent initiatives targeting general practitioners to provide more preventive services.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

While French health care is largely financed publicly, provision of care remains overwhelmingly private. Most medical practitioners are self-employed, and nearly twice as many hospitals are private and for profit in France than in other developed countries. Given this high degree of autonomy, fragmentation of care constitutes a major issue.

Hospital Care

France has 3,089 hospitals, with a total of 377,000 beds for approximately 67 million people, equal to 6.3 hospital beds per 1,000 people. This is more than double the number of hospital beds per capita in the United States (2.9 per 1000 people), while Germany has more beds per capita but fewer hospitals. Hence, hospitals are typically much smaller in France than they are in Germany. Although the total number of hospital beds has decreased over the past decade, closing hospitals remains politically perilous. According to one policymaker: “We’re unable to close hospitals that need to be closed because it would be politically unacceptable.” This has led to many small, isolated hospitals.

Many more of the French hospitals are private than in other European countries. Fully 36% of all French acute care hospitals are private. Of those, nearly three-quarters of them are for profit. Taken together, these hospitals employ nearly 300,000 physicians. Similar to other countries, private, for-profit hospitals in France typically specialize in a limited number of highly profitable procedures, such as elective percutaneous coronary angiograms, upper and lower endoscopies, and joint replacement surgery.

FRANCE LAGS BEHIND other developed countries in introducing EHRs and other information technologies. In 2004, France launched its first attempt at a national health record, the Personal Medical Record (Dossier Médical Personnel, or DMP). Despite high hopes, adoption rates were poor and, even after a redesign and relaunch in 2010, uptake continued to languish. As of 2014 the overall adoption rate was only 67%. As one physician explained, “It’s unclear to whom the EMR ‘belongs’… interconnectedness is poor, and there’s a low level of trust.”

When combined with an already fragmented delivery system, the lack of a uniform electronic record has significantly impeded high-quality care. France also has less advanced imaging equipment per capita, although it has similar levels of use. Further, although all French citizens have an electronic health insurance card (Carte Vitale), the card doesn’t currently contain any health information.

Ambulatory or Outpatient Care

At a rate of 6.3 annual consultations per person per year, the French visit physicians slightly less often than people in other developed countries but much more frequently than Americans. French physicians see an average of 2,020 patients per year, similar to the rate of other developed countries but substantially lower than Canadian and Taiwanese physicians.

As with hospitals, fragmentation of care remains a central issue for France. Most practitioners remain in solo practice and are largely autonomous. As one physician observed,

Physician practices are largely single-person practices. Groups and coordination are rare.… There’s very little incentive, given the current fee-for-service structure.… And specialists don’t talk to generalists—there’s a sense that “they wouldn’t understand.”

Another physician I spoke with noted, “It’s not rare for patients to have to repeat tests 2 to 3 times.… It’s to the point where you have to carry around your own X-rays.” However, this situation is changing, and most younger physicians are beginning to work in group (maison de santé) and multidisciplinary practices (pluridisciplinaire).

There are no preferred provider networks of physicians and hospitals. There is no selective contracting in France with physicians’ groups and only limited ways for health funds to penalize underperforming physicians. Moreover, as Dr. Durand-Zaleski explained, enforcement of gatekeeping—preventing patients from seeing a specialist without a primary care physician referral—is quite limited: “You just have to tick a box saying that you have a gatekeeping physician” to bypass this hurdle.

Mental Health Care

Similar to other developed countries, since the 1960s France has undergone a slow trend of deinstitutionalization. Most mental health care is now provided on an outpatient basis under the responsibility of a local team attached to a psychiatric hospital. According to one’s area of residence, patients are automatically attached to a psychiatric sector (secteur), a geographical area of roughly 70,000 inhabitants. In each sector a mental health team decides the most appropriate type of care. Mental health care in the sector is free of charge. In addition, patients can choose to be treated by a private mental health physician and/or a private mental health hospital with the same financing rules as any other disease. SHI provides funding for inpatient and ambulatory psychiatric care and covers it at the same rates as nonpsychiatric care. However, care by a psychologist is not included under the statutory health insurance, although some VHI plans do cover their care.

Long-Term Care

In France a relatively high proportion of inpatient beds (about 15%) are dedicated to rehabilitative care, while fewer are dedicated to long-term care. The majority of long-term care institutions are public (54%), although the number of private, not-for-profit and for-profit institutions is increasing.

Preventive Medicine

Ambulatory physicians typically administer cancer screening and immunization. Historically, the rates of screening for breast, colon, and cervical cancer in France have been significantly below the European average. The same goes for vaccination rates for hepatitis B (83%) and measles (91%). Dr. Fabian Calvo, chief scientific officer for Cancer Core Europe, notes that this is part financial and part cultural: “There is a lack of funding for preventive care, including cancer screening, and these fields are not considered as prestigious for providers.”

Recently the national government has introduced nationwide screening campaigns. For instance, for colon cancer the government will mail eligible individuals reminders to undergo a colonoscopy twice and will then send them a fecal-occult blood test at home if they do not see a physician. Similarly the government has made childhood vaccination both free and obligatory and offered physicians incentives to council adolescents on sexually transmitted diseases. The definitive impact of these measures is yet to be fully assessed.

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

France is the world’s 5th largest pharmaceutical market, with an approximate size of $37 USD billion. This translates to 12% of total health care spending, or $637 USD per person per year. This is about 45% of US spending and 67% of Swiss spending per person. In absolute dollars, this is 12% higher than the OECD average. High consumption of prescription medications drives this higher-than-average expenditure.

Coverage Determination

After the European Medicines Agency (EMA) evaluates a drug for safety, effectiveness, and quality, it is automatically approved for licensure in France.

The French High Authority on Health (HAS) then evaluates the medication’s scientific validity and grades its absolute and relative benefits.

The HAS Transparency Committee first categorizes the degree of absolute health benefit—known as the medical service rendered (service médical rendu, SMR)—by examining the new drug’s clinical attributes. It considers the drug’s demonstrated efficacy, side-effect profile, and the severity of the condition being treated. It then grades the drug’s health benefits on a 5-level scale ranging from irreplaceable to major, moderate, weak, or insufficient. This designation is important: patients taking medications designated as irreplaceable are reimbursed 100% of the cost, while patients taking drugs providing a major improvement are reimbursed at 65% by the statutory health insurance. Conversely, drugs designated insufficient are not paid for at all. Prescription drugs deemed moderate are covered at 30% of cost and weak prescription drugs at 15%.

The HAS then assesses the new drug’s relative efficacy by comparing it to existing therapies already on the market. This is known as an improvement in additional benefit (IAB). It rates the new drug’s relative performance in one of 5 tiers: (1) major therapeutic improvement, (2) significant improvement, (3) moderate improvement, (4) minor improvement, or (5) no improvement. Thus, a drug, such as a statin, could have major health benefits in an absolute sense but represent no improvement over drugs already on the market.

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (France)

These absolute and relative health benefit designations last for 5 years by default but can be reassessed at any time if new data emerge. Recently HAS received criticism for being slow to review products. As one physician noted: “HAS decides when they decide to decide.… The entire process is getting slower and slower, with more and more committees.”

Price Regulation

After approval and grading by HAS, the Economic Committee for Health Products’ (CEPS) pharmaceutical section reviews the available clinical and economic data to negotiate a price with the pharmaceutical company.

First, CEPS collects an economic dossier that includes a proposed price and sales projections. Using an informal external reference pricing, the proposed price must be in line with neighboring countries or else CEPS can reject it. This serves as a price ceiling for reimbursement. In addition, drugs classified as having a relative benefit compared to other drugs that is designated as major or significant as well as a sales projection greater than $22.5 USD million (€20 million) per year have an additional economic analysis performed by the Economic and Public Health Assessment Committee (CEESP), a committee within HAS. This was the result of a 2012 law that increased HAS’s power to use economic criteria to assess drugs.

Second, CEPS reviews the available data by assessing absolute health benefit (SMR), relative health benefit (IAB), reference pricing indexed to the 4 largest European nations neighboring France—Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK—and comparisons with drugs with similar therapeutic benefits. It then submits its own price proposal. For medications deemed to be of minor therapeutic improvement, the price is set at the level of the nearest competitor. Generics and those deemed to have no improvement have discounted pricing, generally at least 40% below the brand-name drug’s cost. Importantly, SHI is not legally allowed to reimburse medications deemed to have neither therapeutic nor cost benefit. For novel medications there is usually a good deal of negotiation between the company and CEPS. If negotiations fail, CEPS has the power to unilaterally set prices.

Ultimately, CEPS submits a final price proposal, which is then put to a vote. Once passed, it becomes national law. After this, National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM) sets the reimbursement rate based on the absolute and relative health benefits, and then the health minister then gives final approval before listing the new medication in the official register. Subsequently, prices are reevaluated at least once every 5 years.

To keep prescription drug costs low, France has adopted 2 additional practices. First, France has established a national limit on annual pharmaceutical spending growth. Above the growth cap, companies must pay the government 50% to 70% rebates on any additional revenue. The 2020 target growth rate for total pharmaceutical spending is 0.5%.

Second, CEPS has frequently used price-volume contracts to lower sales of high-cost drugs. Reimbursement for Gilead’s hepatitis C drug Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) is illustrative. In 2013, Sovaldi was approved in the United States at a price of $84,000 USD (€75,000) for a 12-week course and made widely available. Citing its immense price, the UK initially refused to cover the treatment. France took an intermediate approach and negotiated a price-volume contract in which they paid $46,000 USD (€41,000) and capped volume at 15,000 doses. CEPS then gave strict prescription criteria so that only the medically sickest 15,000 of the 200,000 hepatitis C patients in France would be treated. Costs were limited because, as is law in France, if total sales went over the negotiated amount, Gilead would be legally obligated to pay back the difference.

CEPS’s strong central negotiating power has achieved remarkable control over drug pricing. The pharmaceutical retail price index for France is 61, nearly half that of the United States (100), Germany (95), and Switzerland (88). And this translates into real savings: whereas Germany consumes 6% fewer pills per capita, it spends nearly 40% per capita more due to higher prices. For instance, in the case of the statin Crestor, when it was branded, a one-month supply cost $86.40 USD in the United States, $40.50 USD in Germany, $25.80 USD in the UK, but only $19.80 USD in France.

This system has kept prices under control despite France’s high share of branded drugs. In fact, only 30% of the prescriptions are generic, significantly lower in other developed countries.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

The French have several mechanisms regulating how physicians prescribe medications. First, certain classes of medications are only covered in specific settings. Some medications, such as powerful antibiotics and antifungals, can only be prescribed in hospitals. Others, such as certain forms of anticoagulant medications, can only be started on an inpatient basis. Prescribing these medications in inappropriate settings is not covered under SHI, and providers could be held liable for adverse events.

Second, certain medications can only be prescribed by certain specialists (prescription réservée à des médecins spécialistes). For instance, ivabradine, a drug used in advanced heart failure, can only be prescribed by cardiologists, while riluzole, an expensive orphan drug used for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease), can only be prescribed by neurologists.

Third, certain exceptional medications (médicaments d’exception) can only be prescribed with preapproval. These exceptional medications are either expensive or innovative and have very specific indications delineated in the drug information sheet (fiche d’information thérapeutique).

France continues to have high levels of prescribed medications. There are no penalties for physicians who prescribe significantly more drugs than their peers. Whereas France has average prescriptions for antihypertensive drugs, cholesterol-lowering agents, antidiabetic drugs, and antidepressants, it has high levels of other types of medications, including benzodiazepines. As one physician explained, “In France, there is a perception that if I visit my primary care physician and he didn’t prescribe me a drug, then what did he do? He must not be a physician!”

Prices Paid by Patients

In France the price of drugs for patients is quite low compared to other countries. All medications deemed to be irreplaceable are covered 100% of the pharmacy cost, while VHI typically handles the coverage gaps for prescription drugs with lower therapeutic ratings. Moreover, medications deemed to have lower health benefits that are used to treat chronic illnesses are covered 100% through the ALD program. This lack of cost sharing has affected the French public’s relative insensitivity to pharmaceutical costs and perpetual high sales volumes.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

France has 226,000 physicians serving a population of 67 million, or roughly 3.3 physicians per 1,000 population. This is in line with the OECD average. Of all physicians, nearly 46% provide primary care. The preponderance of generalists is due to the Ministry of Health limiting the number of specialist training spots in an effort to curb spending. The majority of both generalists and specialists are either fully or partially self-employed.

Roughly half (44.3%) of French physicians are female, in line with other developed countries and significantly higher than the percent in the United States (34.6%). In addition, France has a relatively low share of foreign-trained doctors, just 10.4%, while the percentage in Norway is 38% and Switzerland is 27%. France also has among the oldest physician workforce in the world. In 2017, nearly half were aged 55 or older. This is significantly higher than the OECD average. This is largely driven by a lower-than-expected rate of retirement by older physicians. (Reforms in 2003 and 2009 enabled retirement-age physicians to continue to practice.) To compensate, the French Ministry of Health increased the number of training spots by about 15%.

France’s physicians are some of the most geographically concentrated. For instance, there are 2.7 physicians per 1,000 people in rural areas, with 3.9 per 1,000 people in urban areas. However, for some specialties there are 8 specialists in urban areas for 1 in a rural geography. The maldistribution and “physician deserts” are a consequence of the freedom that France offers its practitioners. As Dr. Agnes Couffinhal described, in the French system the physician is “the king. He sets up shop anywhere he wants and can leave as he pleases.” Moreover, incentive programs to encourage physicians to move to more rural and underserved areas have been largely unsuccessful, as many physicians who take advantage of them only stay for a year or 2. As policymakers say, they “take the money and go.”

In general French physicians make more than their European counterparts but half of what their US counterparts earn. Privately employed primary care physicians earn about $127,000 USD (€113,000), while privately employed specialists and surgeons earn an average of $208,000 USD (€186,000). However, primary care physicians working in public facilities earn much less, about $95,000 USD (€85,000) per year. The divide between compensation for specialists and generalists has increased over the past several decades. Between 2005 and 2015, while specialists’ take-home pay increased 1.6% per year, generalists saw their wages increase by only 0.8% per year.

While there is a comparatively low salary, especially compared to Germany and Switzerland, French physicians have other financial advantages. They do not pay for malpractice insurance. Moreover, depending on their sector placement, they have a variety of government financial benefits, including subsidized social security taxes.

Similar to other European nations, college and medical school are functionally merged in France. After completing high school, aspiring French doctors begin with 2 years of basic science education, referred to as “Cycle 1” (Premier Cycle d’Études Médicales), similar to US pre-medical coursework, and then take a competitive exam that determines eligibility to move forward, similar to the United States’ MCAT. They then take 4 years of in-classroom and in-hospital medical education, referred to as “Cycle 2” (Deuxième Cycle des Etudes Médicales), similar to US medical school curricula. They then have 2- to 5-year residencies at hospitals to complete their clinical training, similar to US residencies but generally shorter in duration. When combined with 2 fewer years of tertiary education, French physicians can begin to practice independently 3 or more years sooner than their American counterparts.

There are 34 medical schools in France that train just over 8,000 physicians each year. The Ministry of Health sets the number of training spots available each year centrally (numerus clausus), although this strict quota will be eliminated in 2020. There has been considerable controversy surrounding the Ministry of Health’s restriction of the number of physician trainees. Medical education in France is free.

Nurses

As of 2015 France had 9.9 nurses per 1,000 people, about the average of developed countries. Nurse practitioners have not yet been nationally recognized, and expanded scopes for nonphysician providers remain rudimentary.

Compared to nurses in neighboring countries, nurses make significantly less money. French nurses earn on average $42,500 USD (€38,000) per year, compared to $53,700 USD (€48,000) per year for nurses in Germany. In fact, French nurses are some of the only nurses in the world to earn less than the average workers.

To obtain a bachelor’s degree in nursing in France, a student must first pass an entrance exam and then complete a 3-year training program at a university-affiliated program. Upon completion, nurses routinely pursue additional training to subspecialize in field such as pediatrics. Despite the president calling for the nation to embrace nurse practitioners in 2014, their roles are yet to be defined, and higher payment has yet to be realized.

CHALLENGES

There are 5 major challenges facing the French health care system. First, France must find a way to coordinate care better, especially for the elderly and individuals with chronic illnesses such as diabetes, heart failure, and COPD. The current system of care delivery is highly fragmented, and the vast majority of physicians practice independently and without a functional national electronic health record. Care coordination is in its infancy and has led to lackluster chronic disease management and increased spending over unnecessary testing. As Dr. Zaleski stated bluntly, “Care coordination is a disaster.” This is exacerbated by difficulties modernizing the hospital system and closing smaller hospitals and limited abilities to regulate quality of care. With the growing burden of chronic illnesses, this is a major challenge for improving care.

Second, while France has controlled prices through strong central oversight, its continued dependence on a fee-for-service payment model for physician services and DRG payments for most hospital care creates systemic incentives for wasteful spending. Volume thus remains high and rising rapidly in terms of office visits, hospitalizations, and consumption of pharmaceutical products. This has led to high costs and increasing physician and nonphysician provider dissatisfaction and burnout. Although alternative payment models have been successfully implemented for some generalists, they remain a tiny fraction of total payments. Bundled payments and other alternative models must be expanded to include the majority of generalists and specialists.

Third, preventive health care services, both vaccinations and cancer screenings, are relatively poor and need improvement. Although many in France live long lives, a significant proportion of this can be tied to healthy diet and higher-than-average levels of physical activity. Rates of immunizations and cancer screenings are among the lowest in Europe. Preventive health care is underfunded and underutilized. Some efforts in this direction have been undertaken, such as making vaccinations for children both free and obligatory. However, further public health measures to reduce tobacco and alcohol consumption, especially among the young, are also warranted.

Fourth, inequalities in care must be addressed. Although France undeniably has excellent access to care, it continues to use an awkward 2-tiered payment system. With recent reforms continuing to expand access to VHI, the line between what is mandatory and what is voluntary is being blurred. Perhaps it is time to expand the range of covered services to include the “fringe” benefits of dental and eye care. Moreover, France continues to struggle with encouraging physicians to move to more underserved rural areas of the country.

Finally, the French health care workforce remains largely traditional and physician based. Expanded roles for nurse practitioners should be explored.

Good truly is the enemy of great—at least in France. French health care is, if not anything else, assuredly “good.” Life expectancy is high, costs are not unbearable, and—although there remain significant areas in need of improvement—there is broad domestic approval of the current program. As one physician put it, “everyone agrees… health care is not a salient political issue in France.” In this way the hybrid French system largely delivers what it promises: universal access to health care in an easily accessible and largely affordable way.