CHAPTER SIX

GERMANY

For people who cherish patient choice, Germany is pretty close to ideal. There is free choice of sickness fund (insurance company), hospital, and physician, all with pretty minimal co-pays. Physicians and hospitals are extremely convenient, and access is pretty convenient too. On average Germans have a primary care physician within 15 minutes of where they live. And Germany is one of the few countries to have solved the financing of long-term care with a dedicated tax.

Although Germany has a reputation for efficiency, the health care system—with over 100 sickness funds—is anything but efficient. As one health policy expert said, “It is hard to know what [the sickness funds] add to quality, cost, or care coordination.” About 99% of benefits are the same between funds. In addition, all the funds collectively bargain with physicians, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies regarding fees and prices. They have almost no selective contracting and networks of high-performing providers. “While sickness funds could be more active in checking quality of performance and ensuring appropriate utilization of services, they are lazy.”

Every expert and government health official recognizes there are too many German hospitals, many of which lack essential services such as stroke units or cardiac catheterization facilities. But, as one government official noted, Germany is doing so well that no one wants to confront the hard choices and expend the political capital it would require to close unnecessary and underperforming hospitals: “A booming economy means it is easier to buy out people than change the health care system.”

HISTORY

The Franco-Prussian War ended in 1871, resulting in the official political and administrative unification of the German state. Kaiser Wilhelm I became the head of state, and the conservative aristocrat Otto von Bismarck became the chancellor. In response to industrialization, which fostered worker unrest, the desire for unionization, and advocacy for socialism, Bismarck instituted a number of social welfare programs, from workman’s compensation and disability insurance to retirement pensions. His aim was to undermine workers’ support for socialism and the Social Democratic Party by acceding to some of their demands for better protections against risk during the tumultuous societal transformations caused by industrialization.

The Health Insurance Act of 1883 was a major component of Bismarck’s social welfare program. It created the world’s first statutory health insurance scheme. At first, health insurance was limited to urban industrial workers, skilled craftsman, and other blue-collar workers in commercial enterprises—just 10% of the population. “Sickness funds” administered the health insurance, and these were mainly attached to workers’ place of employment and governed by boards elected from the workers and employers. Based on the preexisting guild system, there were initially almost 19,000 sickness funds associated with different companies across the country. Contributions from both workers and employers financed the system. Workers paid about two-thirds of the premiums and employers about one-third.

By the start of World War I, workers in the transportation, agriculture, and service sectors were covered by mandatory health insurance, and by the end of the war in 1918 the unemployed were integrated into the insurance scheme. By 1926, half the German population had health insurance coverage through the statutory health insurance (SHI) scheme. Farmers, however, did not receive coverage until 1972. Three groups have been excluded from the statutory health insurance scheme and are required to purchase private health insurance: civil servants, the self-employed, and high-income earners.

Initially the point of health insurance was not to pay for health services but to mitigate wage loss due to illness. But as the effectiveness of medical services improved and costs for these services increased, sickness fund payments shifted to covering diagnostic and therapeutic medical services. At the start, sick workers received up to 50% of their wages in cash for 13 weeks, with additional coverage of ambulatory care, drugs, and treatments. Over time additional services were covered: mandatory maternity pay in 1919, hospital care in 1936, and preventive care and annual check-ups in 1970.

Early in the 20th century, physicians became worried about encroachment on their professional autonomy by sickness funds and began demanding higher fees. In response, the government created the Imperial Committee of Physicians and Sickness Funds to define the health insurance benefit package and the delivery of ambulatory services. This committee made fundamental changes in governance and payment in 1931, when the Weimar Republic was collapsing and hyperinflation was ravaging the German economy. Ambulatory physicians were granted a legal monopoly over outpatient care. They were required to be members of their Regional Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians. Payment for services flowed from the sickness funds to these regional associations that, in turn, paid their physician members for their ambulatory care services. This abolished individual contracts between physicians and sickness funds, replacing them with a uniform contract covering all ambulatory care physicians and sickness funds. Another consequence of this was that it rigidly divided care between ambulatory care physicians, governed by and paid through these regional associations of physicians, and hospital-based physicians, paid by the hospitals. This division persists today.

When Germany reunified in 1990 after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Communist East German health system was disassembled and integrated into the West German system. It is the West German system that exists today.

Since reunification there have been 14 major pieces of health reform legislation, 3 of which have ushered in fundamental changes. First, the Health Care Structure Act of 1993 replaced geographical, occupational, and employer-based assignment to sickness funds with free choice by the individual, with the option of changing sickness funds annually. To minimize risk selection, sickness funds were paid a risk-adjusted amount from the central health fund. Second, the Statutory Health Insurance Modernization Act of 2004 increased workers’ financial contributions for insurance by 0.9% of wages, fully instituted DRG payments for hospitals, and created the Federal Joint Commission (Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss [GBA]) to negotiate most of the reimbursement rates and other policies between sickness funds, physicians, hospitals, and other entities in the health system. The SHI Modernization Act also introduced co-pays of $11 USD (€10) per day for hospitalizations, $5.40 to $11 USD (€5 to €10) for ambulatory care services and products, and $11 USD (€10) per quarter for physician and dentist visits—this quarterly co-pay was eliminated by a unanimous parliament vote in 2012. Finally, the Act to Strengthen Competition in Statutory Health Insurance, enacted in 2007, made health insurance mandatory and universal for all Germans and created a central financing pool that collected payments and redistributed risk-adjusted premiums to the sickness funds.

Despite extensive reforms over nearly 150 years, the German health care system has 3 enduring and defining characteristics. First, it is committed to the fundamental principles of solidarity and universality. All Germans both contribute to fund the system based on income and receive the benefits based on health need, not geography or wealth. In addition, spouses who do not earn an income as well as children are covered without an additional contribution or co-payments, and those with serious chronic diseases are further subsidized through rather generous exemption regulations.

A 2nd characteristic of the system is self-government by the payers, hospitals, physicians, and patients. From the beginning, government involvement in the health system was minimized in favor of self-government by collective organizations that represented the various actors in the health care system. Bismarck wanted the federal government to collect premiums and pay out benefits, but his political opponents worried this would give his government excessive power. Instead, the administrative and financial power was assigned to the nongovernmental sickness funds based around employers. As a result, various nongovernmental commissions have been empowered with legally binding authority to negotiate details of the health insurance system, such as reimbursement rates and benefits. During Hitler’s rule these self-government arrangements were preempted, and the government enforced some of the worst Nazi practices, such as prohibiting Jewish physicians in the statutory health system from treating non-Jews. Because of this abuse, the commitment to empowering nongovernmental, self-governing commissions with administrative and financial authority was reaffirmed and strengthened. Today it is fair to say that the most important body overseeing health care in Germany is not the federal government but the Federal Joint Commission.

Finally, the German statutory health system has shown impressive endurance over the past 135 years. Despite abuse by the Nazis, the fundamental values of the system have persisted. As health policy expert Reinhard Busse and colleagues note, Germany’s health care system has had

remarkable resilience: it survived, with key principles intact, different forms of government (an empire, republics, and the dictatorships), two world wars, hyperinflation, and the division and subsequent reunification of Germany.

COVERAGE

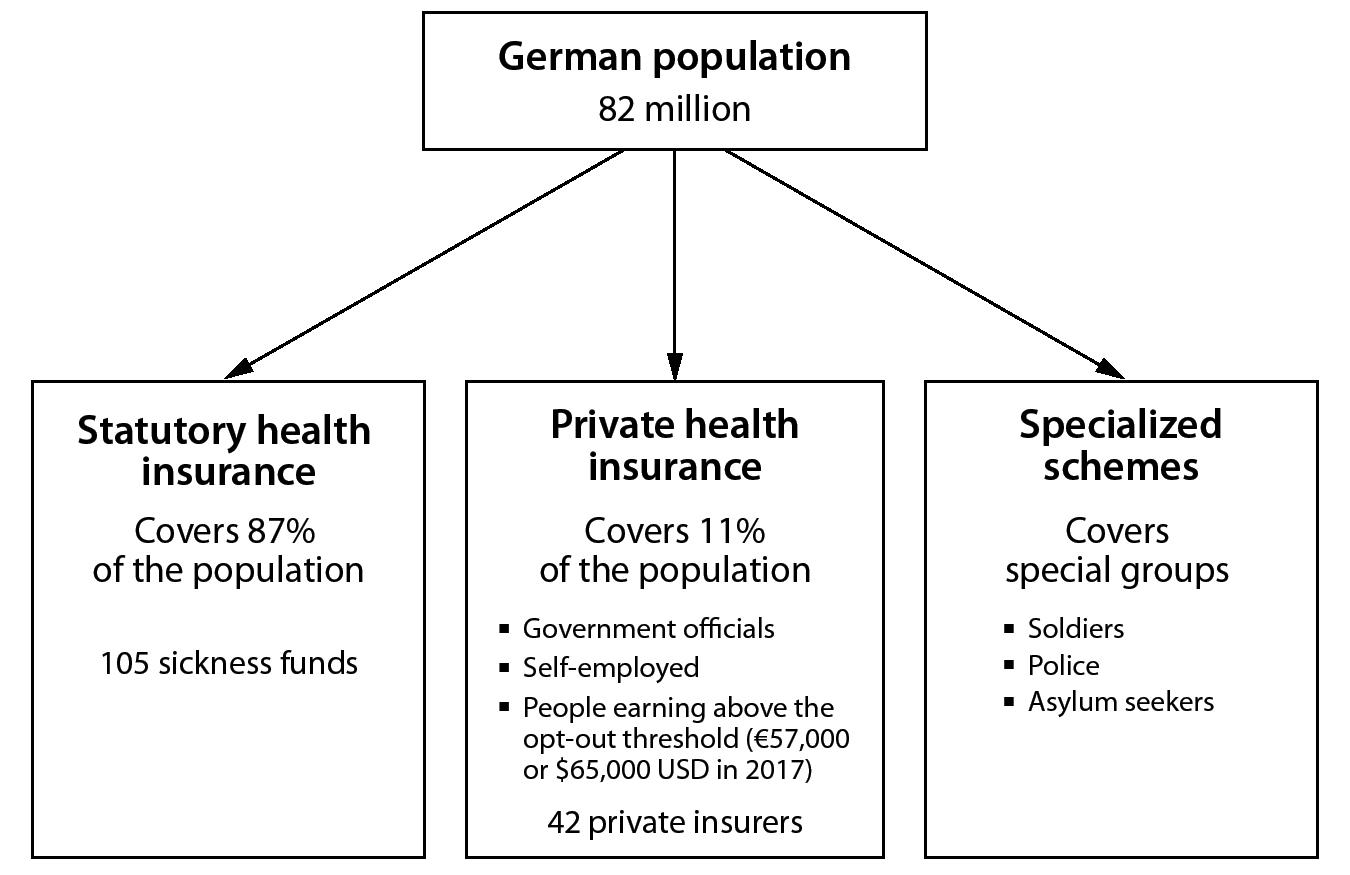

The German health care system has 2 major and one minor component, each of which covers different segments of the population.

First, the SHI scheme—the descendant of the original Bismarckian system—covers approximately 87% of the population, including privately employed workers and their dependents, students, the unemployed, and retired workers. The SHI is not a single-payer system. Instead, patients are covered through the approximate 105 sickness funds (as of January 2020). Traditionally, individuals were assigned to sickness funds based on geography or occupation, but the Health Care Structure Act of 1993 granted Germans the right to choose among sickness funds annually beginning in 1996. The 5 largest sickness funds have over 33 million members, representing 47% of the SHI market.

Individuals insured through the statutory health insurance system can purchase supplementary private insurance to cover amenities and benefits not covered in the SHI, such as private hospital rooms and dental prostheses. A large number of Germans—just under 30% of the population—purchase this supplementary private insurance.

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (Germany)

The 2nd main component is the private health insurance system. It covers 11% of the population. Three groups are eligible to purchase private health insurance: (1) government officials—ministers, members of Parliament, and civil servants, including current and retired government workers as well as teachers; (2) the self-employed; and (3) people earning over the “contributory income,” or opt-out threshold, which was $62,200 USD (€57,600) in 2017, for 3 calendar years in a row. The self-employed and employees with high incomes can opt out of the statutory system and buy private health insurance. In order to prevent gaming—insuring with the private system when young and healthy and switching to the statutory system when older with more chronic conditions—opting into the private system is a onetime, lifetime, and (nearly) irrevocable decision. Once a person is in the private insurance sector, it is almost impossible for them to return to the SHI system. In 2018, there are 42 private health insurers in Germany.

Finally, a small minority of special groups, such as soldiers, police, and asylum seekers, receive their own special government health insurance.

FINANCING

Overall, Germany spends 11.5% of its GDP ($406 billion USD, or €376 billion) on health care, accounting for about $6,200 USD (€5,740) per capita in purchasing power parity. Of this, approximately 77% is publicly financed.

Statutory Health Insurance (SHI)

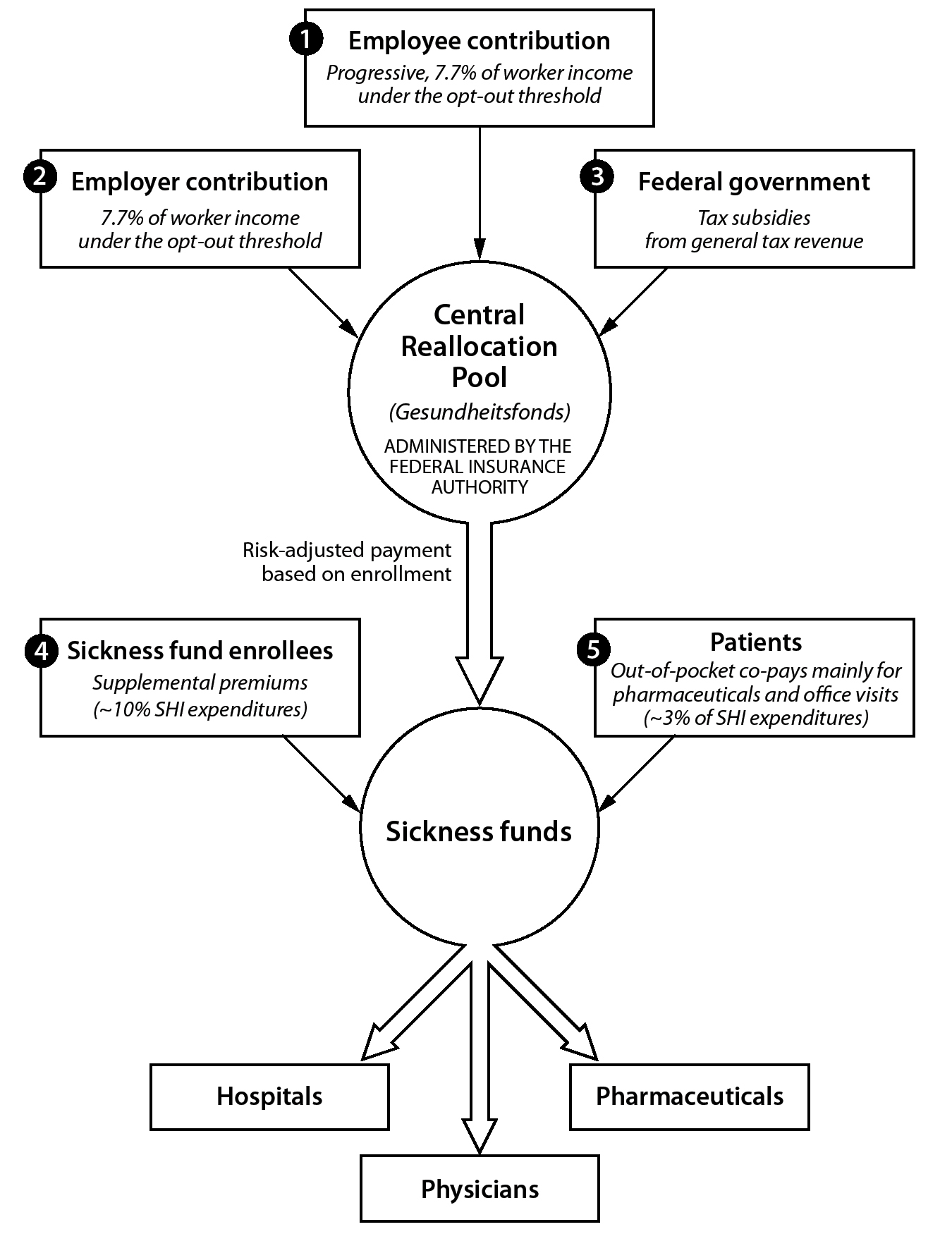

The SHI is funded from 5 distinct sources: (1) employee contributions, (2) employer contributions, (3) government subsidies, (4) sickness fund supplementary premiums, and (5) patient out-of-pocket payments.

Employees’ and employers’ contributions are progressive, based on a worker’s income below the contributory income or opt-out threshold into a SHI funding pool. With both worker and employer contributions, the assessed amount totals to 14.6% of a worker’s income. Between 2015 and 2018, the contributed amount was not evenly split. During this period workers paid more than employers, contributing about 53% of the total, or about 7.7% of their income. As of 2019 the share between employees and employers is equalized again. Retirees contribute based on their pensions, the unemployed contribute based on their unemployment benefits, and university students contribute a uniform amount based on the government stipend for students. There are no contributions for nonearning spouses or children. Since 2009 this money is collected by the sickness funds but deposited directly into the Central Reallocation Pool (Gesundheitsfonds) administered by the Federal Insurance Authority.

The 3rd source of funds comes from the federal government in 2 forms. Because the payroll payments are insufficient to fully finance sickness fund expenditures, the government provides a subsidy of about 7% of total expenditures directly to the Central Reallocation Pool. In addition, the government pays sickness funds a fixed amount for providing specific services, which are not directly linked to health insurance, such as contribution-free coinsurance and reproductive services such as maternity care, in vitro fertilization, and contraceptives. Fourth, when expenditures exceed revenues from the Central Reallocation Pool, sickness funds charge enrollees supplementary premiums, which, beginning in 2019, are shared equally between employers and employees. These premiums are in the range of 6% of sickness fund expenditures, or 1.1% of wages. But these premiums are highly variable between sickness funds based on their efficiency and are a main basis for competition among the funds.

Figure 2. Financing Health Care: Statutory Health Insurance (Germany)

The final piece of financing for health care services in the SHI is patient out-of-pocket expenditures. The 2 largest out-of-pocket expenditures are the purchase of pharmaceuticals and co-payments for physician office visits. Some groups are exempt from co-payments: low-income individuals, patients with high health needs, and children under 18. For instance, the average German is exempt from co-pays once they have spent more than 2% of their gross income, while a patient with a chronic illness is exempt once they exceed 1% of gross income in co-pays. Co-payments are a very small part of SHI expenditures, only about 3% of the total, but are very visible and politically charged.

After collecting all the money, the Central Reallocation Pool pays the sickness funds a risk-adjusted amount for each enrollee. The risk adjustment is based on age, sex, and the actual illnesses of patients. Sickness funds cannot run a deficit.

Because contributions to the sickness funds are linked to workers’ income below the contributory threshold, the amount of money available depends on employment, wages, and population. A high unemployment rate, a high number of dependents, and a high number of pensioners all decrease the amount of money flowing into SHI. Conversely, a good economy with a high labor force participation rate increases the amount of money going into sickness funds.

Sickness funds are capitated and carry full financial risk for their enrollees. Although the SHI system covers 87% of the population, overall contributions to the SHI only account for 57.4% of the total German health care spending.

Private Health Insurance

Private insurers can offer a variety of insurance packages. The packages usually contain benefits that are better than those available in the SHI, such as choice of physician to treat a person in the hospital. But it is also possible to buy high-deductible plans and plans that exclude specific benefits. Premiums are risk rated and, consequently, vary by age, sex, and medical history at the time of enrollment. Unlike the SHI scheme, premiums must be paid for spouses and children. Thus, young, healthy individuals and childless couples with incomes above the contributory threshold have the most incentive to enroll in private health insurance.

To protect people who might not make substantial incomes, such as the self-employed or retired, there is a minimum-benefits package, or basic tariff. The basic tariff must cover benefits equivalent to those in SHI at a premium that cannot exceed the worker assessment at the contributory limit to the SHI—that is, the highest contribution level to the SHI. This price is available only to those who are over 55 years of age, low income, or newly entering the private health insurance system.

Civil servants have 50% of their health bills covered by the government and must buy private health insurance to cover the remainder of the costs. Employed individuals with private insurance have 50% of their premium paid for by their employer, up to 50% of the average SHI contribution.

Because opting into private health insurance is nearly irreversible, private insurance companies are legally required to set aside a portion of the premium from working individuals to cover their health care costs when the workers retire and are no longer earning income. As of 2009 a substantial share of these reserves follow the insured individual even if they switch private insurers.

In general, private health insurance plans in Germany are indemnity plans; patients pay physicians and other providers and are then reimbursed by the insurer. This reimbursement is limited to fixed multiples (1.7 or 2.3, depending on the services) of the official price list set by the government in the official Catalogue of Tariffs for Physicians.

The private health system, distinct from supplementary insurance for SHI, covers 11% of the population and accounts for approximately 9% of expenditures.

Long-Term Care

Currently 21.4% of the German population is over 65, and general population growth is low. Historically, municipalities financed long-term care, but this became a drain on municipal budgets as the population aged. Thus, in 1994 the government enacted mandatory statutory long-term insurance. All Germans must contribute to long-term care insurance. Overall 87% of the population receives social long-term care, and about 12% have supplemental private long-term care insurance.

Long-term care insurance is financed like health insurance. Employed individuals pay 1.275% of monthly gross income, and employers match that payment. Pensioners pay the entire 2.55%. Childless individuals pay an extra 0.25% based on the understanding that they are less likely to get family care in the home as they age. Because payments do not cover the full cost of long-term care, people are encouraged to buy supplemental private long-term care insurance. The government subsidizes these purchases.

Public Health

Individual preventive services, such as cancer screenings, are part of SHI and funded through the health insurance system. States (Länder) establish and cover the cost of public health offices responsible for the nonindividual public health measures such as surveillance of communicable diseases, diagnosis of STDs, supervision of infections in hospitals and outpatient offices, and food and drug contamination. The Federal Ministry of Health is responsible for funding population-wide health education and promotion.

PAYMENT

Payments to Hospitals

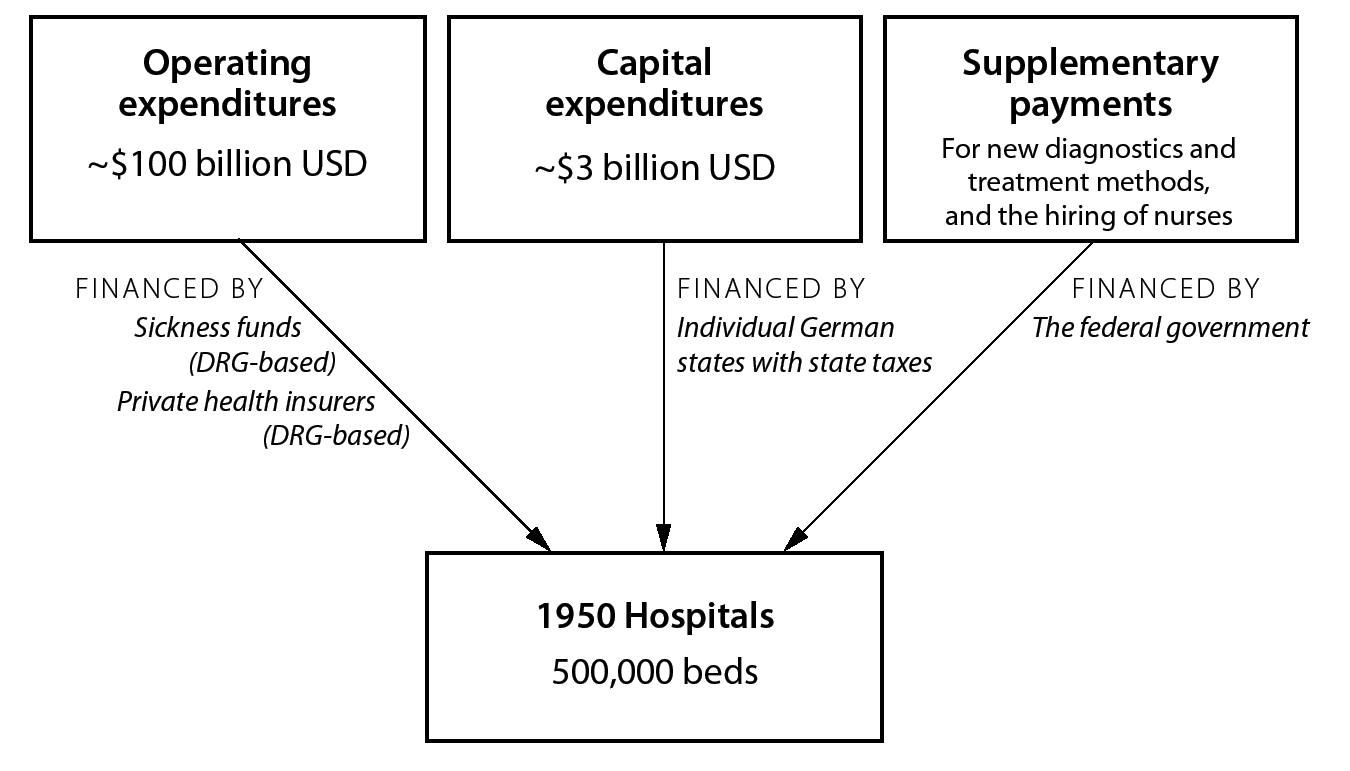

Overall hospital payments account for approximately one-third of total German health care spending—about $108 billion USD (€100 billion) in 2017. Since 1972 hospital funding has been bifurcated.

Capital expenditures for building hospitals, expanding and renovating facilities, and purchasing big equipment come from the individual German states to the hospitals in their geographies and are financed at the state level through state taxes. Capital investment by the German states in hospital facilities and equipment is approximately $3 billion USD (€2.8 billion) per year and is widely considered too low. There have been recent efforts to increase this funding, especially for IT.

Hospital operations costs are paid by sickness funds, private insurance, and self-paying patients.

As of 2004 German hospitals are paid for operations based on DRGs. Each patient is assigned one of over 1,100 DRGs based on major diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, medical procedures, demographic characteristics, and length of stay. These DRGs are created and updated by the Institute for Reimbursement in the Hospital (Institute fur das Entgeltsystem im Krankenhaus [INEK]) at the federal level. Relying on actual cost and utilization data from German hospitals, the German Hospital Federation and the associations of sickness funds and private health insurers negotiate each year on the cost weights for each DRG—how much each DRG is worth and will be paid. These cost weights are calculated at the state level; hence, DRG payments are the same within each state but vary among states by about 10%.

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (Germany)

There are many exceptions to the DRG payment system. Supplementary payments are made to hospitals for highly specialized services, specialized centers, and very expensive drugs. Similarly, there are so-called new diagnostic and treatment methods (Neue Untersuchungs-und Behandlungsmethoden [NUB]) payments, which are payments to hospitals covering innovative diagnostic or treatment interventions such as experimental cancer therapies. These payments are determined on a case-by-case basis by the Federal Joint Commission and mainly benefit university-affiliated hospitals. There are also supplements to help hire more nurses. Altogether these supplements account for almost 20% of payments to hospitals.

The statutory health insurance and private insurance pay the same DRG with the same cost weights. But depending upon their plan, privately insured patients may have supplementary payments that cover amenities such as single rooms and ensuring that the chair of the department is their attending physician. These extra payments incentivize hospitals to admit more privately insured patients.

To ensure hospitals do not skimp on care because of DRGs, they must submit data on over 400 process, structure, and outcome indicators. They are subject to regular review for how they code patients in order to prevent upcoding and the use of low-value interventions. To further incentivize improvements in quality, 2016 legislation requires sickness funds to initiate pay-for-performance reimbursement.

Patients have little financial responsibility for hospital payments. Within the SHI they are assessed $11 USD (€10) per day for a maximum of 30 days. And, as with other co-pays, the poor and individuals with chronic illnesses are exempt.

Payments to Ambulatory or Office-Based Physicians

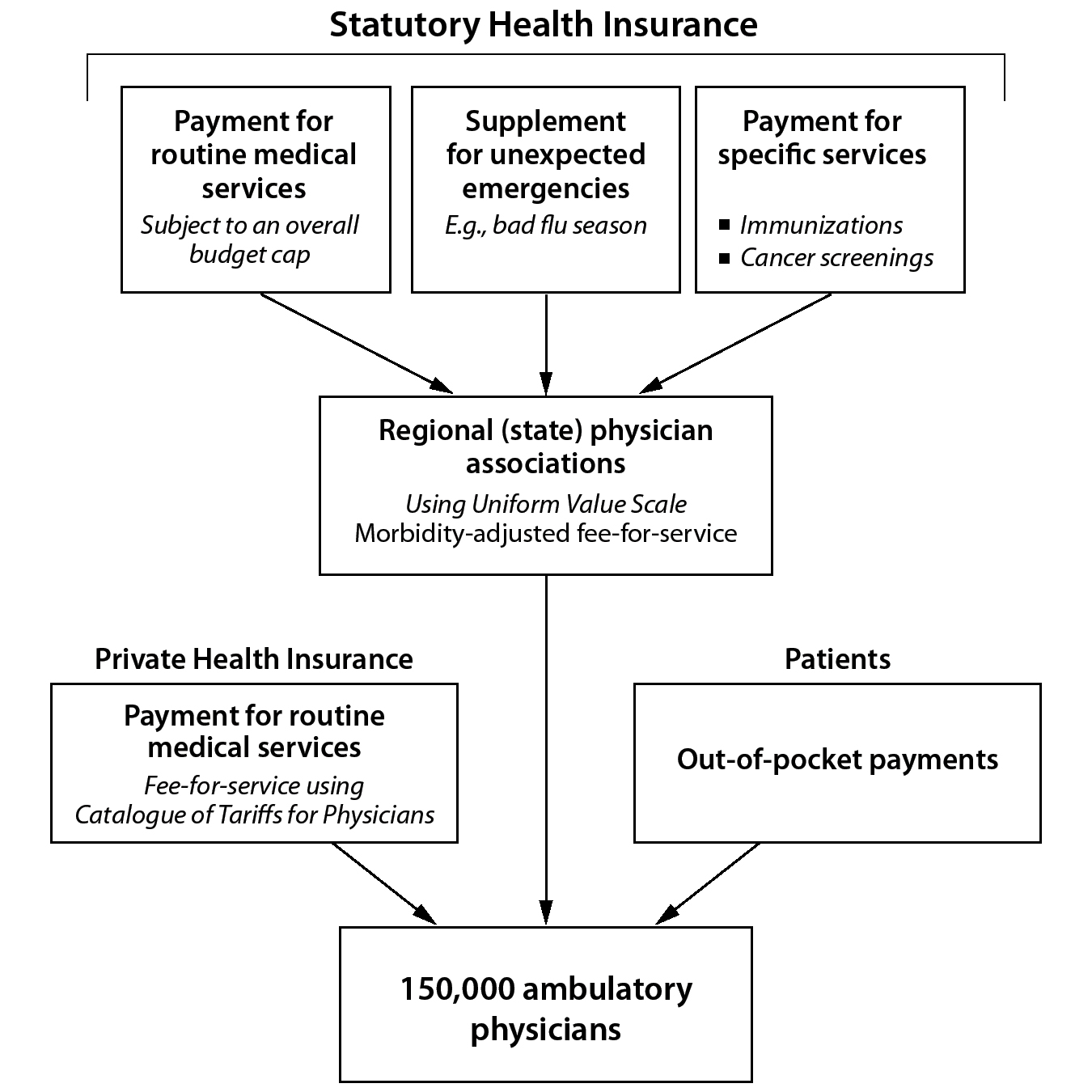

There are 5 different kinds of payments to ambulatory physicians, 3 of which come from the public SHI system. First—and by far the largest—is a morbidity-based payment for services delivered to patients. This payment is subject to an overall budget cap determined at the regional (state) level. Second is a potential supplementary payment based on unexpected medical emergencies, such as a bad flu season. Third are payments for specific services such as immunizations, ambulatory surgery, and cancer-screening tests. These are paid on a fixed fee schedule and are not subject to a budget cap. The 4th payment is fees for services rendered to patients with private insurance. The final payment is out-of-pocket patient payments for services not covered by the SHI, such as travel vaccines.

The actual payment to physicians is a bit more complex and reduces compensation because of an overall cap for SHI services. Annually, the overall payment to ambulatory physicians providing SHI care is negotiated at the regional (state) level between the association of sickness funds and the association of SHI physicians. The level of payment is supposed to reflect anticipated services and be based on the health needs of the state’s population, derived from data on the use of services from 2 years prior to the actual negotiations, such as using 2014 data for 2016 payments. The sickness funds then transfer money to the physician association, which in turn pays the individual physicians based on their submitted billings.

The payments to physicians from the regional physician association are based on the Uniform Value Scale, negotiated by a committee of the Federal Joint Commission, which specifies the billing point value for every possible service covered by the SHI. Like the US RVU system, these points are based on 2 components: (1) the physician’s time and (2) technical support needed to deliver the service. Thus, procedures requiring substantial technical supports have high points, whereas services such as home visits or office discussions that do not require technical support have few points. The points are converted to actual money values at the regional level and vary between regions.

Figure 4. Payment to Ambulatory Physicians (Germany)

Every quarter, physicians submit the number of billing points they actually provide to all patients. The regional physician association checks these points and then pays the physicians. In most states, the number of billing points submitted by physicians exceeds the total remuneration negotiated with the sickness funds, so physicians’ actual payment is lower than the value of the billing points they submit and, thus, the services they rendered. How much lower is not known until all physicians in a region have submitted all their billing points and the regional physician association can determine how far over budget the points are for that year. Reductions are a fixed percentage across all physicians in the 2 pools.

There are 2 further complexities in the payment system for ambulatory physicians. The total budget to pay physicians is divided into 2 different pools, one for family and primary care physicians and one for specialists. Consequently, if specialists bill significantly more points, this does not lower payments to primary care physicians. Second, there are special services provided only by some physicians, such as bronchoscopies or ultrasounds. These are termed qualification-based services. Specifying a budget for these special services ensures that their volume does not increase, thereby siphoning significant payments to the few physicians that perform high volumes of these procedures.

Ambulatory physicians caring for patients under the SHI complain that they end up providing a significant amount of uncompensated care. They submit their quarterly points but do not know how much they will actually be paid until months later. And if the collective points of all physicians in the region exceeds the budget, they are penalized. Despite this penalty, they feel an obligation to provide care and not turn away patients even if they are not compensated for the services. A member of the Federal Association of SHI Physicians described physicians’ frustrations with the payment system:

After a quarter of the year, a physicians’ office sends the number of visits and procedures to the state Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung [statutory health insurance system]. Those numbers undergo control mechanisms to check the times and ensure they comply with regulations. Eventually they are finalized, and about 6 months later the doctor gets paid by the state Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung. But it looks in its cash register and finds out “we don’t have 100% of the money to pay you, we only have 90%.” Then the physician only gets 90% of what was sent in, even though [the physician] rendered the services and they were approved as valid. And even worse, you never know in advance how much you will be paid because you don’t know personally how many patients have been seen by all the other doctors in the state. It is a blind flight, no instruments.

This perspective about the deficiencies of payment to physicians is not universally shared. The uncertainty in payment is not large. Moreover, the reason for the cuts in payments are because physicians tend to overtreat, and as a group, physicians have rejected other policy approaches to reducing overtreatment. Plus, German physicians find other ways to make income, such as charging patients for activities not typically covered by SHI, such as travel vaccinations.

Physicians treating patients with private insurance, however, receive fee-for-service payments. They are compensated based on the billing points in the Catalogue of Tariffs for Physicians, not the Uniform Value Scale used for SHI services. The points are multiplied by a factor to convert them to actual money values. Treating physicians can then multiply the money value by 3.5 to produce the maximum charge rate. Payments are typically lower than this maximum charge rate, usually around 1.7 to 2.3 times higher than the calculated money value. But only physicians who work in certain areas—urban areas with high incomes, such as Munich, and high numbers of civil servants, such as Berlin—are likely to have a sizable number of privately insured patients.

Payments for Long-Term Care

People must apply for long-term care payments. The Medical Review Board reviews applications, and approximately two-thirds are approved for one of 3 types of payments. First, there are monthly cash payments to reimburse for in-home care provided by family members. Second, there are fee-for-service payments for professional home care services. Finally, there are per diem payments for institutionalized nursing home care.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Sickness funds do not cover most complementary and alternative medicine services. Payments for these services come from private, supplementary insurance, or from out-of-pocket payments made by individuals.

Preventive Medicine

Sickness funds and private health insurance pay private, ambulatory physicians for most primary prevention services such as immunizations, cancer-screening tests, and health education. These payments are negotiated between the associations of sickness funds and SHI physicians. However, they are separate payments not subject to the budget caps.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

The German health care system is a consumerist paradise. Patients with SHI have totally free choice of sickness funds, hospitals, and physicians, and co-pays are very low. Although there are wait times, especially for high-demand specialists, patients nonetheless have no gatekeepers and have access to any physician in the country. As a physician put it, “A patient can see any doctor, in any region, at any time. You can see 3 orthopedic surgeons and 3 GPs a day if you want. And you can see them all again the next day if you want. There is no limitation for the patient. The patient just walks into the doctor’s office and gets service.”

Hospital Care

There are approximately 1,950 hospitals, with nearly 500,000 beds for approximately 82.3 million people, with 8.2 beds per 1,000 population. This ratio is about 2.5 times that of the United States and is exceeded only by Japan. About 50% of hospital beds are in public hospitals owned and operated by municipalities. Of these public hospitals, 33 are university hospitals. The other hospitals include religiously affiliated, Red Cross, and private hospitals. There are about 19.5 million hospital admissions each year, about 55% of the admissions of the United States, a country with 4 times as many people as Germany. Trends show that the number of hospital beds has slowly declined, but hospital admissions have increased, though with shorter stays. Even with these changes, the average length of hospital stays is comparatively long, at 7.6 days. Experts and commentators suspect that there are many unnecessary hospitalizations, especially for ambulatory-sensitive conditions such as exacerbations of chronic conditions like COPD and uncontrolled diabetes.

Hospitals are mainly inpatient facilities providing surgery, treatment for exacerbations of chronic medical conditions, and other typical inpatient services. When a patient is admitted, a hospital-employed physician takes over managing the care from the patient’s primary care or specialist physician.

Some hospitals—mainly university hospitals—have the right to operate outpatient facilities. These focus on specialized services such as for oncology, hemophilia, pulmonary hypertension, and other complex or rare diseases. There has also been an increase in ambulatory surgical procedures, some of which take place at hospital facilities. Hospitals have a very limited right to or responsibility for post-acute care, such as rehabilitation services or post-treatment home care.

Importantly, hospitals are regulated by the Ministry of Health in each region, not at the federal level. Although they can go to any hospital in the country for the same co-pay, Germans expect to have a hospital within 25 kilometers (about 15 miles) of their homes. As a result, closing hospitals is a highly charged political decision.

Ambulatory (Outpatient) Care

Germans are heavy users of physician services. There are over 150,000 ambulatory care physicians, 45% of whom are primary care physicians. Visits to ambulatory physicians have increased over time and now average about 10 per person per year.

There is very limited selective contracting and a limited but steadily increasing number of physician networks. Sickness funds must pay all physicians who are members of the regional association of SHI physicians, giving patients free choice of any SHI physician. Since the 1990s there have been various efforts to incentivize more integrated care, delivered by a network of physicians coordinated with hospitals. Patients who select these integrated care models can have lower co-pays for physician visits and pharmaceuticals. But both the tradition of free choice of physicians and the rigid divide between hospital-based and ambulatory care physicians mean that Germany is not conducive to integrated care delivery. Thus, in 2015 only 1.5% of all sickness fund payments went to selective contracts for integrated care.

One important change in care began in 2003 through the introduction of disease management programs (DMPs) for patients with chronic conditions. Unlike a formal provider network, which limits access, the DMPs are an attempt to efficiently coordinate care among outpatient providers—both primary care and specialist physicians—using an evidence-based protocol. All the regional sickness funds, in conjunction with the regional associations of SHI physicians, create these DMPs. They include standardized reporting requirements and quality measures as well as patient reminders and reports to physicians on their performance. Sickness funds are paid an administrative fee of about $162 USD (€150) for each patient enrolled in a DMP. Currently there are over 10,000 DMPs covering diseases ranging from type I diabetes and asthma to breast cancer, and they have enrolled over 7 million patients.

Mental Health Care

Beginning in the 1970s Germany underwent a process of deinstitutionalization for patients with mental illness. East Germany followed West Germany, with a lag of about 20 years, deinstitutionalizing after unification. Although the number of inpatient psychiatric beds steadily declined from 150,000 in 1976 to under 40,000 today, community-based care has been inadequate. About a quarter of acute care hospitals have inpatient psychiatric wards, and many have outpatient psychiatric departments. Private psychiatrists and psychotherapists assume the bulk of outpatient mental health care, but there are long wait times for appointments, which is exacerbated in rural communities where psychiatrists are often scarce. These providers oversee a sociotherapeutic benefit that covers housing and social services intended to help avoid unnecessary hospitalization for acute exacerbations of mental health conditions.

There are a growing number of for-profit, private hospitals focusing on substance abuse and psychiatric care.

Long-Term Care

Nearly 3 million (3.6%) Germans receive long-term care payments, and 55% of Germans over 80 years of age receive such payments. About 70% receive payments for in-home care, mostly cash benefits for family care, and about 30% for institutionalized nursing home care. Most ambulatory long-term care is provided by private, for-profit companies, while nonprofit organizations mainly provide institutionalized nursing home care.

Preventive Medicine

Ambulatory physicians provide most individually focused primary preventive activities, such as immunizations and cancer-screening services. Preventive care that is considered relevant to public health, such as the diagnosis of STDs, may also be provided through regional public health offices established by the states. In addition, recent reforms have strengthened prevention, with a focus on health promotion in schools, businesses, and long-term care facilities.

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

Germany is the world’s 4th-largest drug market by revenue, accounting for $58.6 billion USD (€54.3 billion) in revenue in 2014. Approximately 14% of health care spending—or $780 USD (€722) per capita—in Germany goes to pharmaceuticals. Out-of-pocket payments by consumers for drugs make up about 16% of the total drug spending, and Germans consume a relatively high proportion of prescriptions per person.

Coverage Determination

In Germany drugs are granted a license and marketing approval based on European Union regulations embodied in German law. The Pharmaceutical Act of 1976 made the licensing of drugs mandatory. The Paul Ehrlich Institute oversees the licensing of vaccines and blood products, while the Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices reviews applications for licensure of all other drugs. Drugs approved by the European Medicines Agency are automatically approved for licensure in EU member states, including Germany. Manufacturers must demonstrate that the drugs they submit are safe and effective, although marginal effectiveness is all that is necessary; there is no cost-effectiveness requirement necessary for the licensure of a new drug, nor is there mandatory postmarketing surveillance of drugs for their side effects and/or effectiveness. Licensing lasts for 5 years, but it can be renewed. The Federal Institute for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices does not review homeopathic drugs; they merely register with the Institute.

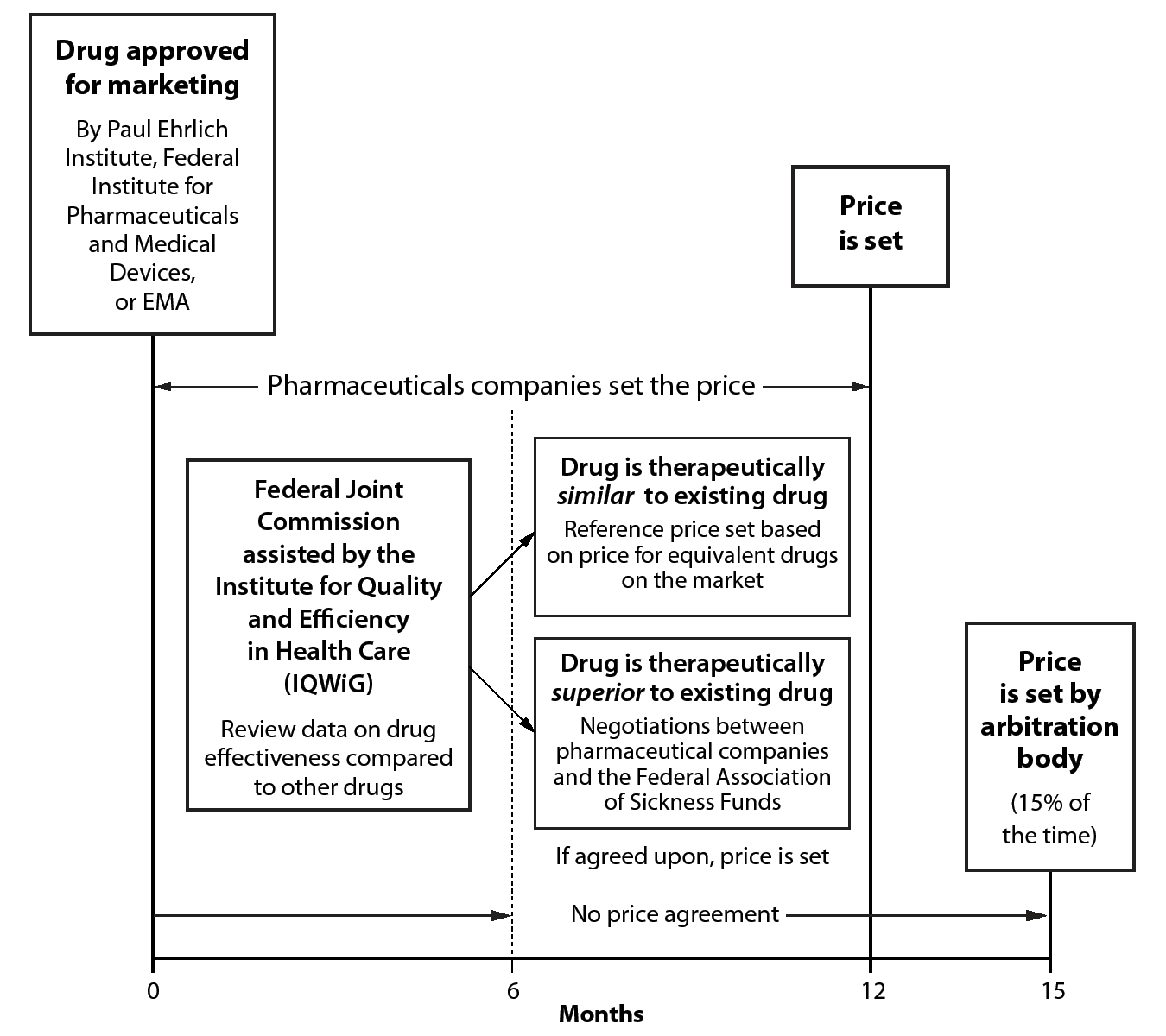

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (Germany)

Germany does not have a list of covered drugs. However, the Federal Joint Commission does specify the indications for the appropriate use of a drug and, thus, what will be paid for. Therefore, a physician may not prescribe a drug not licensed for a specific indication; patients can only be reimbursed for off-label use of a drug if (1) there is no other treatment, (2) it is used to treat a life-threatening condition, and (3) there is some scientific evidence suggesting benefits.

The SHI also does not reimburse over-the-counter drugs except for children under 18 and for adults with select chronic conditions.

Price Regulation

Germany has a rigorous multistep process for determining the price of a new drug that occurs in the 12 months after a drug is allowed to be marketed (Figure 5). For the initial 12 months after market launch, pharmaceutical companies can sell a drug at any price. At market launch manufacturers must prepare and submit a dossier on the clinical benefits and risks of a drug, demonstrating its therapeutic advantages and whether it has additional clinical benefits compared to drugs already on the market. For 6 months after submission of that dossier, the Federal Joint Commission, usually with the assistance of the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen [IQWiG]), determines whether a drug is therapeutically comparable to drugs on the market or whether it has novel clinical benefits.

If the drug is determined to provide no additional clinical benefits, then an internal reference price determines the maximum price the SHI will pay. The internal reference price is derived from the price of the other comparable drugs on the market in Germany. The price does not refer to the prices paid for the drug in other countries. There is no co-pay for consumers on drugs whose price is at least 30% below the reference price, so there is substantial consumer pressure for lower prices.

If the drug is determined to have additional clinical benefits compared to existing drugs, the Federal Association of Sickness Funds and the pharmaceutical manufacturer negotiate to determine the price. The price premium is supposed to reflect the added therapeutic value of the drug, as determined by the Federal Joint Commission. These negotiations decide the price for both the SHI and private insurance systems. If after 6 months of negotiations no agreement is reached, the price is determined by an arbitration body, which has 3 months to render a decision. Price negotiations go to arbitration about 15% of the time.

Sickness funds get 3 types of rebates on the price they pay for drugs. The first rebate comes from pharmacies. The law requires pharmacies to give sickness funds a mandatory rebate, currently under $2.20 USD (€2) per prescription. Second, pharmaceutical manufacturers must provide sickness funds a legally specified mandatory rebate, currently set at 7% for patented drugs and 6% for generics. Finally, there is a rebate, mainly on generics, that is determined through negotiations between pharmaceutical manufacturers and individual sickness funds. In the typical agreement the manufacturer gives the sickness fund a discounted price and the sickness fund designates the manufacturer’s drug the one generic in a specific class of drugs, such as statins, that it will cover for its insured members. This is one of the rare cases in which individual sickness funds do the negotiations instead of the Federal Association of Sickness Funds. Pharmacies are obligated to honor the negotiations by dispensing the specific drug to sickness fund members. This discount/rebate system has significantly reduced drug spending.

Pharmacies set prices for over-the-counter drugs without regulation.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

There are 3 mechanisms to shift German physicians’ prescribing behavior to use fewer and lower-cost prescriptions. First, the Federal Joint Commission issues guidelines for the proper use of costly drugs, and physicians who do not comply can be fined. Second, each physician is given a prescription budget based on drug utilization data for a similar group of patients. If a physician exceeds the budget by 15%, they receive a warning; if they exceed it by 25%, they may need to reimburse the sickness funds. Finally, physicians are given maximum quotas for heavily prescribed drugs, set by negotiations between the associations of the sickness funds and SHI physicians. They are encouraged to use lower-cost drugs in these therapeutic areas. If physicians exceed these quotas, their reimbursements may be reduced.

Prices Paid by Patients

The price patients pay for a drug is the same throughout Germany. Pharmacies are only able to mark up drug prices by a legally predetermined fixed amount—$9 USD (€8.35), plus a 3% margin. Since 2004 German patients have been required to pay a co-pay for drugs, at a maximum of $11 USD (€10) per prescription. These co-pays can be waived if patients are in an integrated care network.

Importantly, unlike in many other countries, German drug prices include the 19% national value-added tax (VAT), making German drugs unusually expensive. If a pharmaceutical manufacturer sets the price above the maximum reference price, the patients pay the difference. Due to the resulting consumer pressure, few prices are above the reference price maximum. In addition, there is a mandatory generic substitution law; if a drug is prescribed, the pharmacist is required to dispense the generic unless the physician specifies not to.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

There are approximately 350,000 physicians in Germany for a population of 82 million, or 4.5 physicians per 1,000 population, which is well above the international average. Of these physicians, 151,000 are ambulatory physicians, and approximately 190,000 work in hospitals, including trainees. About 45% of the ambulatory care physicians are primary care physicians. Primary care physicians tend to be older, whereas younger physicians are increasingly entering specialties. Over 95% of ambulatory physicians take SHI patients; only about 4% of physicians exclusively see privately insured patients. As in most countries, German physicians are more heavily concentrated in the urban areas.

In general there is a rigid separation of ambulatory and hospital-based physicians, but a few hospital-based specialists (mainly chiefs of hospital departments) have ambulatory offices as well. A growing number of specialists are also performing surgical procedures in hospitals on a part-time basis. Although the number of multi-physician group practices and employed physicians has increased, the vast majority of German physicians are self-employed. They work in private, solo, or very small group practices that own their own equipment and employ staff. Self-employed physicians tend to work longer hours than those employed by other physicians or centers. The shift to fewer work hours and more externally employed physicians is associated with an increase in female physicians. If the causal link is accurate, this trend will continue, as 70% of current German medical students are female.

Physician salaries in Germany are lower than in the United States and Switzerland. For instance, an average general practitioner earns approximately $124,000 USD (€115,000). Radiologists are the highest earners, at about $432,000 USD (€400,000), with surgeons earning about $238,000 USD (€220,000). These salaries are from SHI payments. Private insurance contributes about 20% of the total physician salaries in the ambulatory care setting, although this is not evenly divided across the country because patients with private insurance are concentrated in larger urban areas.

There are 35 medical schools in the country, which produce about 11,000 medical graduates each year. Medical schools are funded and operated by regions. Because medical schools are expensive, regional governments do not want to expand their numbers, even though the health system demands more physicians.

Countries that can offer higher salaries, such as Switzerland, are increasingly recruiting German-trained physicians. In turn, Germany is recruiting physicians from Eastern European countries such as Romania.

Nurses

There are approximately 1.1 million nurses in Germany, or 13 per 1,000 population. Approximately 400,000 work in hospitals. There is no real pathway for nurses to become nurse practitioners, nor is there much use of medical assistants or other non-nursing personnel to take over tasks performed by nurses that do not require nurse training.

There is a widely held perception that there is a serious shortage of nurses in Germany. The reasons for the shortage are multidimensional but include stringent staffing rules, like the requirement in neonatal intensive care units that there be one nurse per neonatal patient, 24 hours per day. Recently, the government altered hospital payments to provide an incentive to hire more nurses. There is a proposal to separate the payment to hospitals for nurse salaries, which would dictate to hospitals how to allocate their budget for nursing. To satisfy demand, Germany has undertaken several policies, such as increasing the training of nurses, improving nurses’ working conditions, and recruiting nurses from other countries.

In Germany, nursing is neither a profession nor a guild—that is, a specialized craft. Nursing schools are run by a relatively small number of hospitals and are not part of the university education system. Nursing training takes 3 years, and approximately 40,000 nurses are trained each year. Sickness funds pay for nursing education by deducting a small amount from the payment to hospitals without nursing schools and reallocating it to hospitals with these schools.

CHALLENGES

There are at least 7 major challenges facing the German health care system over the next decade. First, the biggest challenge may be the excessive number of hospital beds and hospital admissions. For a country with 25% of the US population, Germany has 40% the number of hospitals, 60% the number of hospital beds, and 55% the number of hospital admissions per year. However, closing hospitals and reducing the number of beds is very difficult. Because capital costs for hospitals are made at the state level and many hospitals are owned by municipalities, closing hospitals is a local political decision, and no politician who wants to be reelected will voluntarily close a local hospital. The only politically feasible reason to close hospitals is demonstrated poor quality or a lack of adequate nursing staff. Whether this will succeed in reducing the number of hospital beds is unclear.

Second, there is perceived to be a severe shortage of nurses. However, Germany has 13 nurses per 1000 people, one of the highest ratios in Europe, indicating that this shortage is more a result of the structure of the system and how nurses are deployed than a real shortage of personnel. This perception also seems to be due to the excessive number of hospital beds in Germany and the lack of clear roles for non-nurses, who could assume many functions currently performed by nurses that do not require nurse-level training. Until the hospital-bed issue is resolved, there may be no resolution to the perceived nursing shortage.

Third, there is a lack of care coordination for patients with chronic illness. The rigid divide between hospital-based and ambulatory physicians as well as the limited use of home health care services have made care coordination difficult. Attempts to improve coordination through DMPs and integrated care have met with some, but limited, success. There are thousands of DMPs, yet they guide care for fewer than 10% of the population. And, despite being available, integrated care is not widely utilized. Care coordination might be improved—although not completely fixed—by requiring hospitals to assume responsibility for posthospital discharge and readmissions, but this would probably be met with fierce opposition from ambulatory physicians. Two policies are needed: reducing the rigid divide between hospital-based and ambulatory physicians and providing greater incentives for integrated care through selective networks. These are major structural changes that will take a long time to occur.

Fourth, it is unclear whether the high number of sickness funds adds value. Patients can choose among different sickness funds, but structural constraints mean that there are not significant differences among them in terms of quality, cost, or service. Sickness funds do have different DMPs and could do more integrated care and quality monitoring, but these do not seem to justify the costs of having over 100 of them. More quality monitoring and the creation of high-quality networks could be valuable, but it is not clear whether this is part of any of the funds’ strategic plan.

Fifth, there is a perceived unfairness of private insurance. There are advantages of having a private insurance system. It provides competition to the SHI. It has large reserves, over $270 billion USD (€250 billion), that will help pay for medical services as the population ages. Nevertheless, there is some sense that well-off individuals and civil servants receive private insurance that is experience rated, so many of them have greater benefits but lower premiums than SHI. But because the very people who have the power to reform private insurance are the ones who benefit from it—politicians and civil servants—reform seems unlikely.

Sixth, Germany is trailing in digitizing health care and adopting EHRs. There are several major digitization initiatives that need to be completed: ensuring medications and emergency data are available on each patient’s health card and the full adoption of a platform that can be used by all stakeholders in the health care system with interoperable EHRs for patients. This may be politically difficult to accomplish. At least at the hospital level, improving the electronic health infrastructure would require capital funding by states that already underinvest in capital projects.

Finally, there is the challenge of long-term care. By 2030, 30% of the German population will be over 70 years of age. This will increase the need for both home and institutional long-term care services. Institutional care is very expensive, and as of 2018, public long-term care insurance covers only about 50% of the cost of institutional care. As the need for long-term care increases, the number of nursing home beds required and the overall cost will strain the system. This demographic and financial challenge will become a major issue in the next decade.

Currently Germany has one significant advantage that is simultaneously a liability. The economy is doing tremendously well with low unemployment, and because the financing of the sickness funds is linked to wages, the system is currently very well-funded. Hence, the system is not under financial threat, even though there are focal areas of financial strain, such as capital investment by states in hospitals and long-term care. But the good economy also creates 2 problems. First, because unemployment is low, there are not many people available for nursing and other lower level health jobs such as medical assistants. This makes it hard to address the need for more nurses and geriatric caregivers. Second, with a good economy and adequate funding, there is little sense of crisis to drive health care reform. There is no real financial pressure to reduce the number of hospitals and hospital beds and develop more integrated care. Few policymakers will face these hard choices if they can avoid them; the system’s strong financial position allows politicians, officials at the sickness funds, physicians, hospitals, and other stakeholders to “kick the can down the road.” But when there is an economic slowdown, these issues will intensify, requiring more comprehensive solutions.