CHAPTER SEVEN

NETHERLANDS

“Dutch huisartsen [general practitioners] are notorious for sending you home with advice to rest and take a paracetamol [Tylenol]. Come back in 2 weeks if you’re not feeling better.”

This is a common complaint about Dutch health care, especially from expatriates. Dutch physicians have a strong tradition of conservative care, intervening hesitantly because, in their view, nature fixes most minor ailments.

This philosophy is embodied in the Dutch health care system. Patients may select any insurer and general practitioner. Primary care physicians have both extensive responsibility and authority. They act as true gatekeepers. General practitioners (GPs) are clinically and financially responsible for chronic and mental health care—often delivered by a nurse practitioner in the office—and a GP referral is required before seeing any specialist. GPs are fastidiously noninterventionist and manage most issues. But when needed, an advanced, innovative, comprehensive, and supportive health care system kicks in, as described by a mother of an infant with a cardiac abnormality that required a month’s hospitalization and surgical repair:

Support from the child developmental staff, pastoral workers, a nutritionist, a pre-speech therapist, a world class surgeon, pediatric home nurse when needed, and incredible nurses, consultants, and trainee consultants.… [W]e had stellar support and amazing care.

All this care was essentially free at the point of service. While adults have a $435 USD (€385) deductible, primary care visits are exempt, and all children under 18 have no deductible or cost sharing.

Special financing extends to the elderly as well. The Netherlands is one of only a few countries to have a dedicated, tax-financed long-term care arrangement for the disabled and elderly. Is it any wonder the Dutch system consistently comes out on top of the Euro Health Consumer Index?

HISTORY

Guilds, Sickness Funds, and Hospitals Before the 20th Century

The Netherlands has a long history of providing health benefits through insurance funds. The German occupation during World War II influenced the modern system, but it has evolved into what is plausibly the world’s purest form of managed competition.

In the middle of the 19th century there were a number of health insurance funds run by physicians, trade unions, and corporations. In 1908, the Netherlands Medical Association (NMG) established the Schreve Commission, which advocated for independent physician practices, free patient choice of doctors, and having nonwealthy patients purchase health insurance while wealthy patients pay out of pocket for services. The Commission also proposed physician representation on the governing boards of health insurance funds so as to ensure physician autonomy was protected. The Commission’s proposals were not immediately enacted.

The 1913 Sickness Act (Ziektewet) was the first attempt at a government mandate for health coverage. It actually provided a kind of unemployment payment to workers who were out of the job due to illness. Further governmental attempts to institute compulsory health insurance schemes were stalled due to World War I, but after the war the NMG, unions, and commercial insurers sponsored a proliferation of competing health insurance funds. To some degree this was successful: by 1941 nearly 50% of Dutch citizens had some form of health insurance.

World War II changed everything. The Nazi occupation brought with it an imposition of the German Bismarckian model of compulsory state insurance provided through competing sickness (insurance) funds and financed by taxes assessed on both employees and employers. The covered benefits included hospital, specialist, and dental care. As in the German system, the well off above a certain income threshold were exempt from the statutory health insurance and purchased private health insurance. The self-employed and elderly could choose between being in the statutory insurance system or purchasing private health insurance. The German rules reduced the number of sickness funds and nearly eliminated all physician-run funds.

The imposed German system remained largely intact until 1966. After World War II premiums in the private health insurance market rose rapidly, driven by the enrollment of larger numbers of elderly and disabled people. Several attempts at addressing the problem—such as transferring the lower-income elderly, disabled, and children into the statutory sickness fund system—failed to fully address the high premiums. In 1966, the Health Insurance Act, Ziekenfondswet, was implemented. In reality, it essentially copied and codified most of the German system wholesale. The only notable change was that the new Health Insurance Act allowed funds greater flexibility to determine their geographic region of operation and introduced an income-based premium. The main goal of the Health Insurance Act was a political one: the Dutch finally had their own system, not one directly tied to the Nazis.

In 1967, the Dutch Parliament passed the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act (AWBZ) to address the issue of long-term care, including care for the disabled. This effectively bifurcated the Dutch system, with one part focusing on curative care, which was further divided into statutory and private systems, and a 2nd part encompassing long-term insurance.

By the 1980s, premium costs had grown rapidly, prompting a growing consensus that the system needed reform. The Health Care Prices Act of 1981 empowered the national government to set global hospital budgets that covered total yearly operational expenses, excluding capital costs. In addition, the government also capped medical specialist expenditures, although these caps were frequently exceeded. In 1986, the Insurance Law on Access to Care abolished much of the private system and moved nearly a million people into the statutory sickness fund system. It also required private insurers to provide benefits nearly identical to those in the statutory system.

Rising costs continued to plague the health care system, and in 1987 the government appointed the Dekker Committee to propose systemic reform. The Committee recommended combining the statutory and private insurance systems into a single system of competing private insurers that all had to provide the same basic benefit package. Income-linked taxes collected by the government and nominal premiums set by insurers would finance the system. People would have the option to purchase supplemental insurance for services not in the basic benefit package, and the Dekker Committee also recommended direct negotiations of fees between insurers and providers. The government tried and failed to enact the Committee’s recommendations multiple times. Finally, in 2006, the Dutch Parliament passed the Health Insurance Act (ZVW), which implemented many of the Dekker Committee’s original recommendations. This is the legal framework for the current Dutch system.

The Dutch system has evolved into one that features competition between insurers for patients, negotiations between insurers and providers, and regular national collaboration across parties to deal with systemic problems as they crop up. On the one hand, the principles of local, managed competition between private, mostly nonprofit providers and private, nonprofit insurers underpins the system. On the other hand, competition is restricted: insurers must offer the same basic benefits package, and negotiations between insurers and providers are far from cut-throat. National agreements—led by the government—between insurers, providers, and politicians identify target levels of health care cost growth, setting a benchmark for reasonable price increases. The ultimate responsibility for the functioning of the health care system lies squarely on the government.

Thus, the Dutch health care system has gone through 3 phases of evolution. From the 19th century until World War II, there was the system of health benefits through an amalgam of insurance companies run by physicians, unions, and commercial entities. From World War II until the mid-2000s, the system was structured with a statutory public system funding private sickness funds and a parallel private insurance system. And, since the 2006 reforms, there has been a managed competition system, with the government allocating premiums to competing sickness funds and residents purchasing supplementary private insurance.

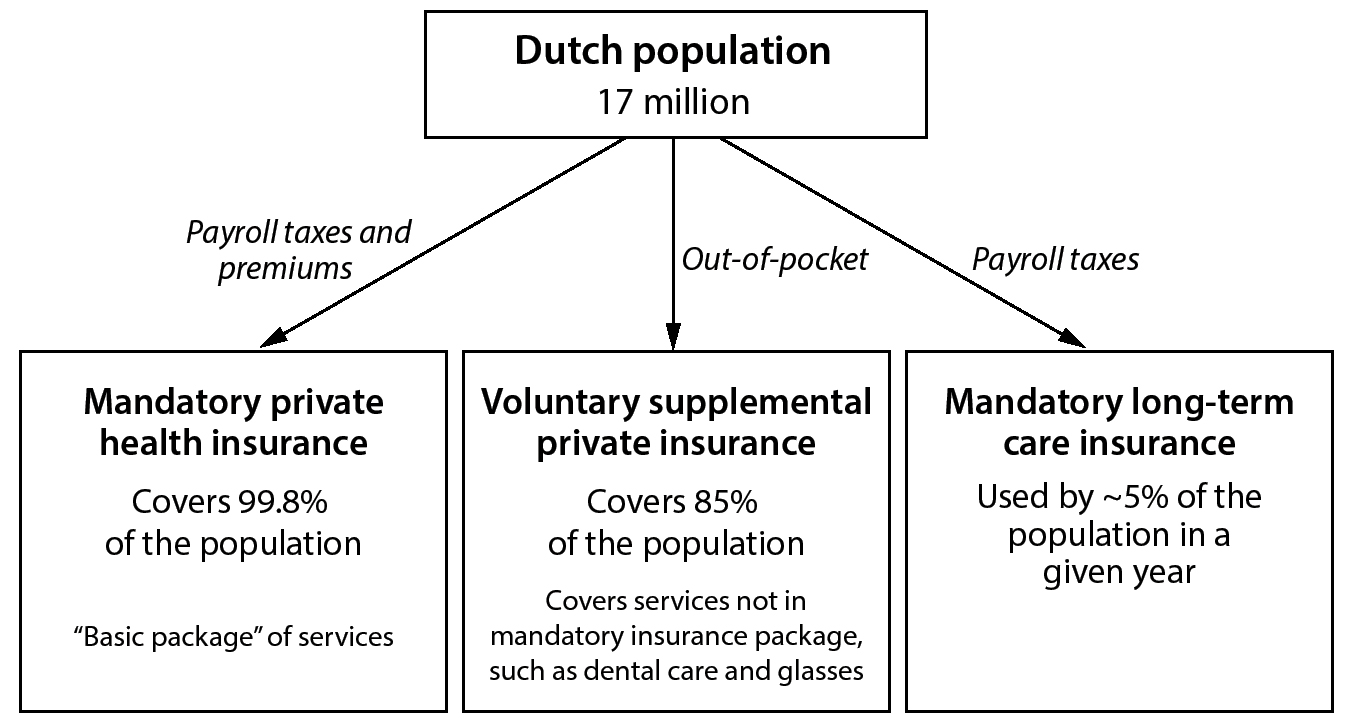

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (Netherlands)

COVERAGE

The Netherlands is a country of 17 million citizens. Fully 99.8% have health insurance. Just over 24,000 people are uninsured, although 223,000 (1.7%) have not paid the entire premium. In addition, 85% of the Dutch population purchases private supplemental insurance.

Insurance coverage in the Dutch health care system is divided into 3 main components: universal statutory insurance provided by competing sickness funds, voluntary supplemental insurance provided by private insurance companies, and mandatory long-term care provided by the government.

Statutory Health Insurance

The entire population (99.8%) is covered under the compulsory statutory health insurance system set up by the Health Insurance Act of 2006. Competing, nonprofit insurance companies set premiums for the same mandated benefits package. Individuals choose which insurer they want for coverage. Payroll taxes cover most of the basic premium, and individuals need to pay a nominal premium for the remainder. The government provides income-linked subsidies to individuals to help pay for these premiums, with about half of all Dutch households receiving some form of subsidy. There are approximately 24 competing insurers that fall under 9 umbrella organizations. The 4 largest groups cover 90% of the Dutch population.

Coverage is essentially universal because the penalty for not having insurance is stiff. As a government official noted, “The penalties are rather tough, and of course, this is a nation of accountants and bookkeepers. So they are also very efficient at finding people who are simply not insured.” After 3 months without insurance, people are fined about $440 USD (€367). After 3 more months the fine is repeated. Finally, the tax office has the authority to automatically sign individuals up for a plan and deduct the premium (minus fines) from wages.

Voluntary, Private Supplemental Insurance

There also is the supplementary, private health insurance system that is voluntary. Voluntary supplementary insurance can only cover services not in the basic benefit packages, such as eyeglasses, adult dental care, and physical therapy. There are no tax breaks or subsidies specifically earmarked for voluntary supplemental insurance, and there is some evidence of adverse selection in the voluntary market. Nearly all enrollees purchase supplementary insurance from the same insurer that provides them with the basic package.

Long-Term Care Insurance

Finally, there is mandatory long-term care insurance funded by payroll taxes. Since 2015, all Dutch residents are enrolled in a government plan that provides up to 24-hour custodial and nursing care, either in institutions or at home. The Social Support Act encourages independent-living initiatives and is administered by municipalities. The Long-Term Care Act finances intensive home health care and institutional care in nursing homes.

FINANCING

In 2017, according to the Dutch government’s statistical bureau (Statistics Netherlands, or CBS), the Netherlands spent $109.3 billion USD (€97.1 billion) on health-related activities, including social supports. Just considering health care services, the Netherlands spent $83.7 billion USD (€74.5 billion), or 10.1% of GDP, equal to roughly $5,000 USD (€4,400) per capita. Fully 80% of health-related spending is either publicly financed through taxes or compulsory health insurance premiums and income-linked subsidies.

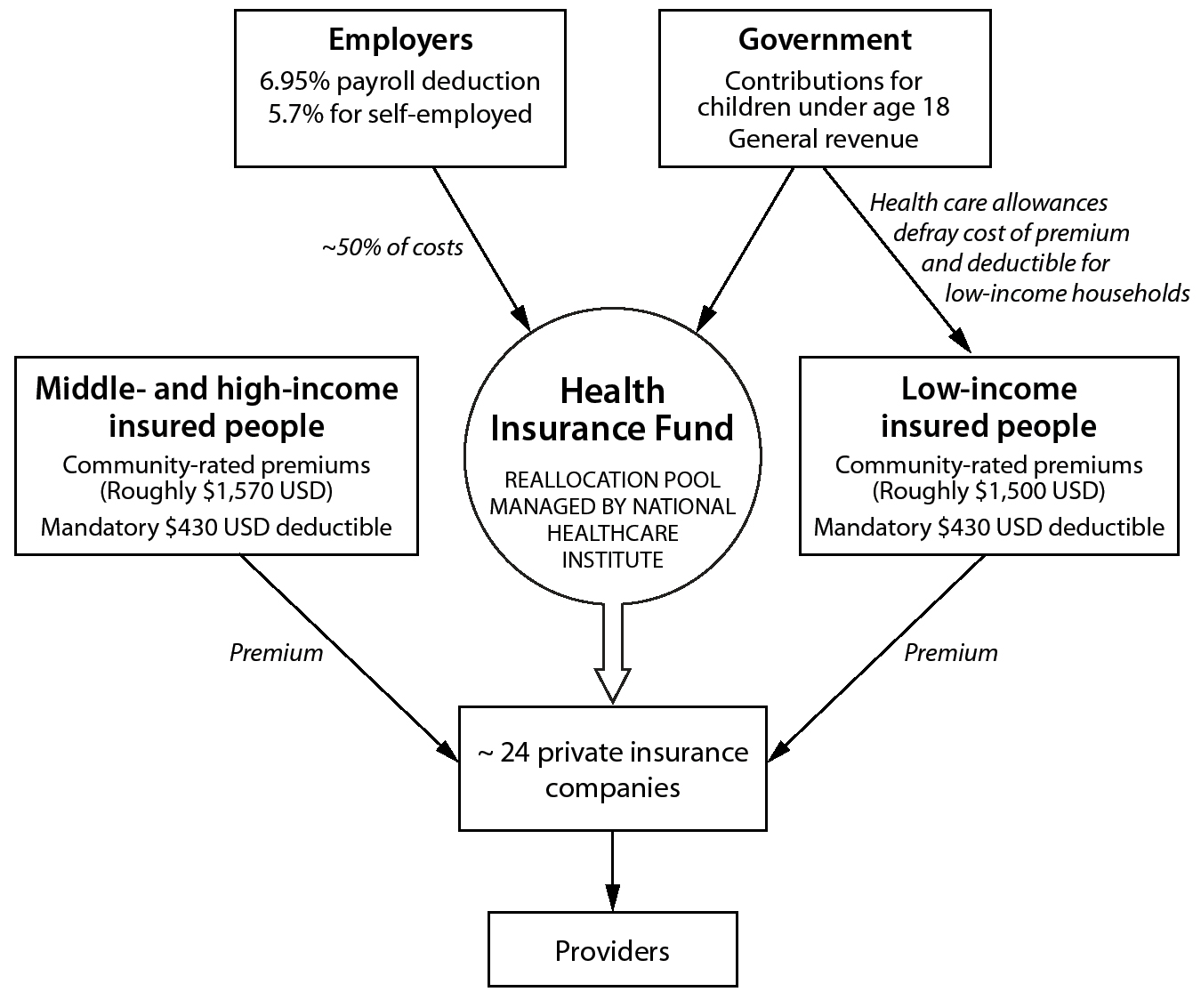

Figure 2. Financing Health Care: Mandatory Private Health Insurance (Netherlands)

Spending on all health care and health-related services breaks down such that about 44.6%, or $48.8 billion USD (€43.5 billion), is spent through the compulsory health insurance system; 4.6%, or $5 billion USD (€4.5 billion), comes through supplemental insurance; and 19.1%, or $21 billion USD (€18.7 billion), is spent on compulsory long-term care insurance. Spending on long-term care is actually higher because much of the funding for long-term care services comes through the compulsory curative care insurance system, such as payment for home nursing care. Individuals contributed about $12 billion USD (€10.7 billion) in out-of-pocket spending, accounting for about 11% of overall spending.

Each year the Minister of Health, Welfare, and Sport sets the national Health Care Budget (BKZ), which creates target growth rates for different categories of spending, such as hospital care and primary care. The minister of health has the authority to order claw-backs from providers and insurers when the Health Care Budget is exceeded.

Statutory Health Insurance for Curative Care

The statutory managed competition system is financed through 4 sources: (1) income-linked payroll deductions from employers, (2) community-rated nominal premiums, (3) state contributions from general revenue, and (4) individual out-of-pocket payments. All insurers cover the same services specified in the basic package by the minister of health. Insurers may only compete on price and quality of the basic package, and price and quality of voluntary supplementary insurance packages that they offer to members.

The government collects payroll deductions, which were 6.65% of income, with a limit of about $60,500 USD (€53,701) per worker in 2017. In 2019, the limit was increased to 6.95% for those with a maximum income of $63,000 USD (€55,927). For self-employed persons the contribution was 5.4% of wages in 2017 up to the same ceiling, which also increased to 5.7% up to a maximum of $63,000 USD (€55,927) in 2019. These taxes are collected in a central health insurance fund that the government then pays to each sickness fund on a risk-adjusted basis. The payments are based on expected health risks, and insurers bear the full risk for medical care, with the exception of long-term mental health services. These payroll taxes account for approximately half of the spending on statutory health insurance.

The National Health Care Institute (ZIN) manages the risk-adjustment process. Insurers must submit claims data. The risk adjustment formula used to pay individual insurance companies is managed by several universities and includes about 200 different variables, from age and sex to drug utilization and socioeconomic status. It does a very good job of reducing insurers’ incentives to engage in risk selection. One professor involved described the process:

A lot of people are coming to the Netherlands to understand how we risk adjust the insurance pool. It is quite comprehensive how we distribute [the premiums], in fact. So there is no real incentive to do some risk selection.… We have more than 200 variables in the model at the moment… we are quite lucky that we have actually quite good data. What happens is that every insurer [reports quarterly what is] reimbursed… to the information center. Here we have algorithms, and we use that increasingly. The quality [of the data] is excellent.

Additionally, regulation prevents insurers from certain types of cream skimming. For example, it is illegal to advertise specifically to young students or higher-income individuals.

Second, households pay a nominal premium to their selected insurer. These premiums are community rated. For an individual the average annual premium was about $1,525 USD (€1,353) in 2017, increasing to $1,550 USD (€1,378) in 2019. The government subsidizes these premiums for joint-filing households with incomes under $42,200 USD (€37,500) and individuals earning under $33,300 USD (€29,500). Importantly, the government pays the full premium for all children under 18.

Private Supplementary Insurance

In addition to compulsory insurance to cover most routine care, individuals decide whether they want to purchase voluntary supplementary health insurance (VHI). VHI plans use experience rating to set premiums and can reject applicants. Individuals are responsible for the full cost of payment. There are neither tax preferences nor other subsidies or incentives for purchasing supplementary insurance. About 85% of Dutch residents have VHI.

Long-Term Care

The Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZA) establishes the national budget for long-term care. Long-term care is financed through 3 sources: (1) payroll taxes, (2) general tax revenue, and (3) out-of-pocket payments.

The Long-Term Care Act, enacted in 2015, assesses a 9.65% payroll tax on employee wages up to $38,600 USD (€34,300) in 2019. This covers about 73% of the cost of long-term care. The National Health Care Institute manages these funds. They are distributed to regional care offices (Zorgkantoren), run by private insurers, in order to pay long-term care providers, and to the Social Insurance Bank (SVB), which manages personal budgets for long-term care recipients.

General taxes are also used to fund custodial care provided by municipalities. These funds are not earmarked but rather are part of government payments to municipalities covering all governmental activities in addition to custodial care, such as roads and sewers. Almost all recipients of long-term care must also pay some portion of the cost out of pocket. The system for deciding how much a beneficiary should pay is complicated, but in general, out-of-pocket costs are means tested based on income and assets. Typically beneficiaries must pay about 10% to 12.5% of their income. Total out-of-pocket costs for long-term care were capped at roughly $2,471 USD (€2,200) per year in 2015. Municipalities may require co-payments for domestic help and social support provided under the Social Support Act.

Out-of-Pocket Costs

Out-of-pocket costs apply for both the basic insurance package and for long-term care. All compulsory insurance plans carry a mandatory $430 USD (€385) deductible, although many services are exempt from the deductible, including GP visits, home nursing care, and services for children. Every year enrollees can voluntarily increase their deductibles to up to $990 USD (€885) in exchange for a lower premium. About 12.6% of enrollees opt for voluntary higher deductibles, and 9.6% take the maximum deductible.

For long-term care, beneficiaries pay some portion of the cost directly to the Central Administration Office (CAK), and municipalities have considerable flexibility to set additional co-payments.

PAYMENT

Since the liberalizing reforms in 2006, payment rates for nearly 70% of all curative care services—including most hospital care and physician services—are negotiated between insurance companies and providers. The prices for the remaining 30% of services, such as for long-term care, are set nationally by the Dutch Healthcare Authority. The specific mechanisms for negotiation and payment to hospitals and providers are exceptionally byzantine, having been described by experts as “governance by confusion.”

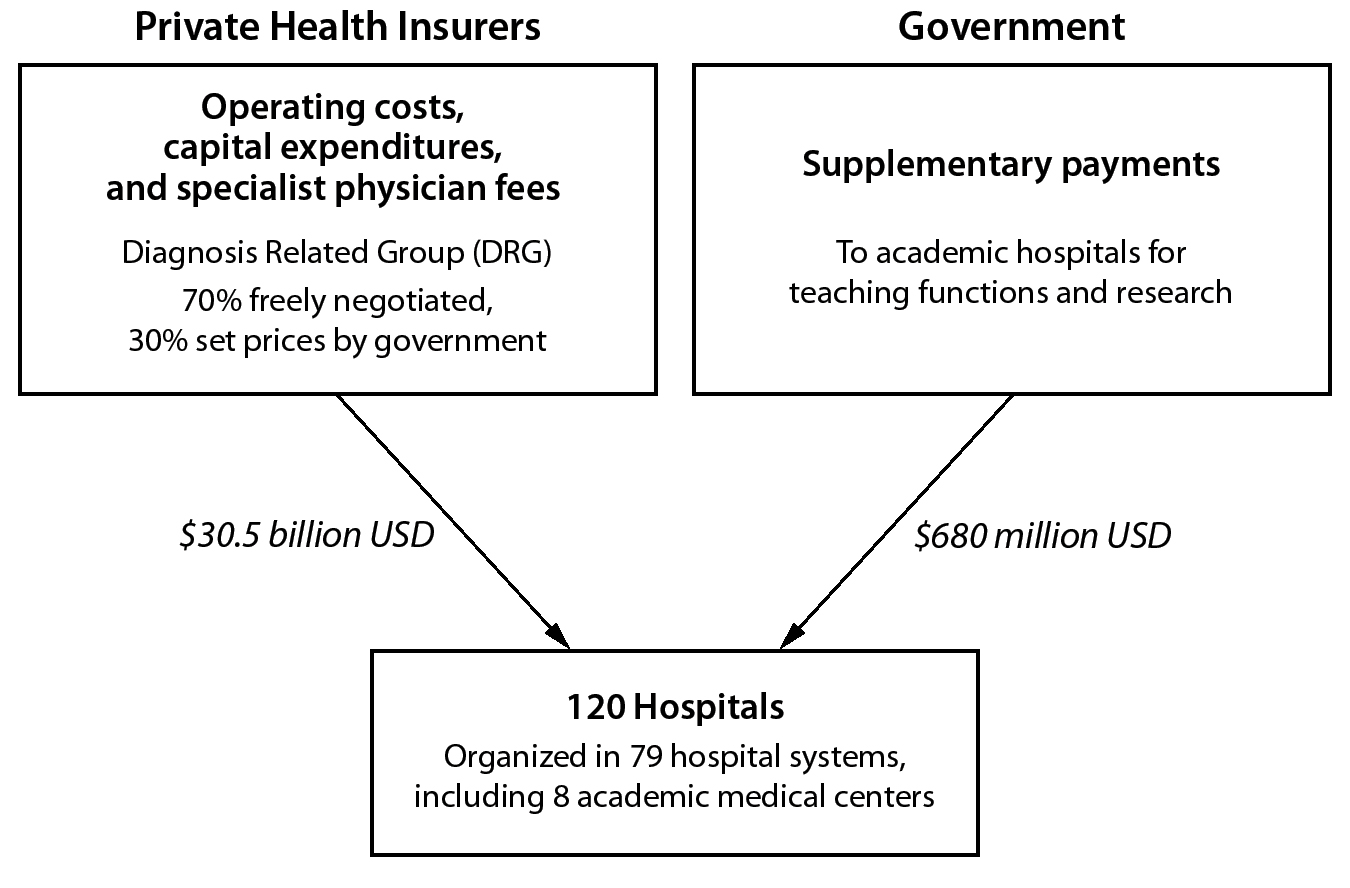

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (Netherlands)

According to the OECD, which only measures health care spending (excluding social supports), in 2017 the Netherlands spent a total of $83.6 billion USD (€74.4 billion) on health care. Of that figure, $28.9 billion USD (€25.7 billion), or 34.6%, of health care spending was for hospital services; $21.8 billion USD (€19.4 billion), or 26.0%, was for residential long-term care facilities; $15.3 billion USD (€13.6 billion), or 18.2%, went to physicians and other providers of ambulatory health care services; and $9.4 billion USD (€8.36 billion), or 11.3%, was spent on medical goods and pharmaceuticals.

Payment to Hospitals

Insurance companies negotiate directly with hospitals. Each insurer establishes its own hospital networks and uses selective contracting. Most negotiations occur on the basis of price and volume. Insurers and hospitals rely on a modified DRG system called Diagnosis Treatment Combinations (DBCs). There are approximately 4,400 DBCs, and the Dutch Healthcare Authority is responsible for updating the list. DBCs cover fees for hospitalization and the work of physicians in hospitals. Insurers can negotiate on the basis of price, such as a rate for each DBC. Insurers can also reach an agreement about a volume of services they will pay for. Insured persons who visit noncontracted providers will typically pay a larger portion of the bill out of pocket. Pay-for-performance and pay-for-quality schemes are in their infancy.

Academic hospitals get extra funding from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport to support their academic functions. In aggregate these payments amount to roughly $680 million USD (€600 million) annually, or 2.3% of total hospital spending. Furthermore, highly specialized surgical procedures, such as organ transplantation and neurosurgery, are performed in only a few hospitals and are paid separately. These payments are regulated by the Act on Specialized Clinical Services (Wet bijzondere medische verrichtingen).

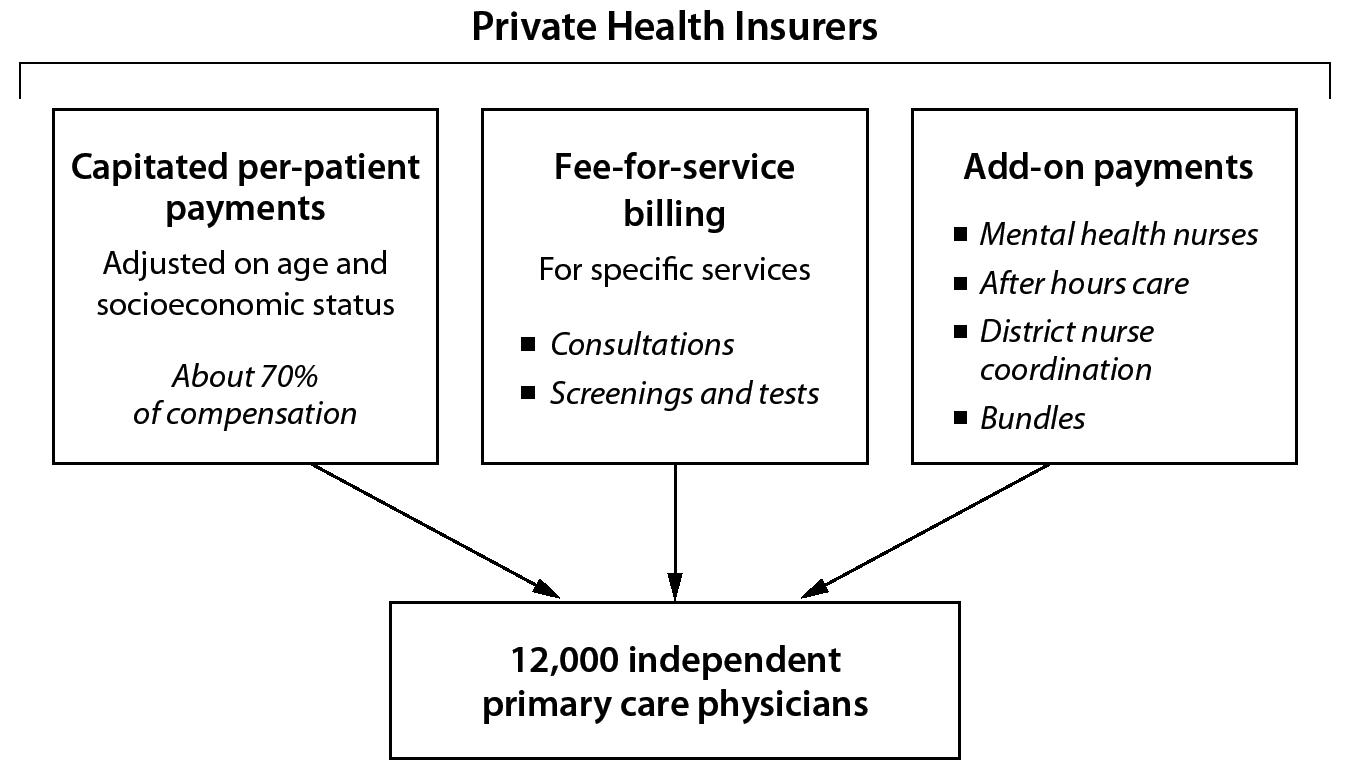

Payment to Physicians

Primary care physicians and specialists are paid very differently. Since 2006, there has been a significant move away from specific fee-for-service reimbursement for primary care physicians. General practitioners are paid based on 3 segments. Segment 1 is a capitated rate that is adjusted for only 2 factors: the patient’s age and socioeconomic status. This capitated rate covers about 70% of total GP compensation. GPs can also bill on a fee-for-service basis for office consultations and home visits, although these fees are quite low. For instance, the fee for a short office visit is $11 USD (€10). Finally, GPs can receive fees for employing nurses for mental health care. Nonetheless, as one professor put it, payment for GPs is “more or less based on how many patients they have [in their panel].”

Segment 2 payments incentivize care integration. They include payments for chronic care nurses and bundled payments for participation in regional care groups dedicated to chronic-disease management, such as for diabetes, COPD, and asthma. Regional care groups that receive bundled payments contract directly with networks of providers. Care groups are legal entities formed by multiple providers, typically led by GPs. For the diabetes bundle, care groups are financially responsible for assigned diabetes patients in the program and can either deliver services directly or subcontract them. The price of bundles in segment 2 is freely negotiated, but the range of services that need to be provided in the bundles is set nationally. Contracts include mandatory record keeping for evaluation purposes. In 2018, additional payments for organization and infrastructure were added to pay for cooperation with district nurses and secondary care.

Figure 4. Payment to Physicians (Netherlands)

Segment 3 payments are pay-for-performance programs largely focused on increasing access, improving appropriate drug prescribing, and incentivizing appropriate specialist referrals. These pay-for-performance programs are voluntary. As part of Segment 3 payments, GPs also receive hourly fees for participating in after-hours care cooperatives that provide nighttime and weekend coverage. Segment 3 is the smallest fraction of GP income.

Medical specialists are paid differently. About 40% of specialists, including pediatricians and psychiatrists, are salaried employees of hospitals. Similarly, within academic medical centers all medical specialists are salaried employees. About 60% of specialists are organized into specialist-owned partnerships (MSBs). The MSB of each specialty negotiates fees with hospitals. The physician fee component of DBCs is paid from hospitals to MSBs, which then pay each member specialist.

Payment to Long-Term Residential and Home Health Providers

Payment for long-term care is highly fragmented. Municipalities, through their Regional Care Assessment Center, determine what long-term, home-based custodial care is appropriate for beneficiaries to be paid for under the Social Support Acts. Municipalities are ultimately financially responsible for at-home custodial care and social supports. Conversely, private insurers pay for home-based nursing care through the Health Insurance Act. The federal government pays for 24-hour care (either at home or in nursing facilities) through the Long-Term Care Act. Long-term institutional support for children is financed separately under the Youth Act.

For custodial home care, patients can receive services from a government-contracted provider, or they can receive a personal budget to organize the care themselves. In the past, personal budgets were paid directly to patients and families, but fraud forced a change to have the Social Insurance Bank manage these budgets. However, not all long-term care services are paid for through the Long-Term Care and Social Support Acts. For example, district nurses who coordinate care and provide health care services at home are reimbursed through the compulsory health insurance system. In 2015, the reorganization of long-term care cut funding for municipalities to provide social support.

Negotiations and Selective Contracting

Fostering competition remains a challenge within the Dutch system. Although insurers can selectively contract, it exists more in theory than in practice. Price negotiation between insurers and hospitals and other providers is less thorough and detailed than might be imagined. Insurers have little capacity to steer enrollees toward specific hospitals. As one researcher noted, “Even if there is selective contracting, people will tend to ask their GP which hospital they should go to.” The penalties for going out of network are not sufficiently high to induce patients to scrupulously adhere to networks. Insurers have been unwilling to raise incentives and penalties for going out of the network. One professor noted the risk-averse nature of negotiations: “Most of the negotiations are incremental.… [The insurers and hospitals] have to work together next year too, so negotiations are usually pretty friendly.”

Because negotiations between insurers and hospitals have been ineffective at reducing costs, the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport has resorted to establishing a national Health Care Budget to set target cost growth to restrict cost increases.

Bundled Payments

Since 2010, the government has introduced a nationwide bundled payment system for diabetes, vascular risk management, and COPD. The Dutch government determines which services are included in each bundle. For example, services in the diabetes bundle are codified nationally in the Dutch Diabetes Federation Health Care Standard (DFHCS). The diabetes bundle includes checkups, eye and foot exams, dietary counseling, lab tests, and consultations with referred specialists, but they exclude medications and hospitalizations.

Insurers freely negotiate prices with entities known as care groups that are financially responsible for the cost of all services in the bundle for a fixed period. In 2011, the latest year for which pricing data are available, bundle prices were between $428 USD (€381) and $516 USD (€459). Care groups are new legal entities in the Dutch system, and they are primarily made up of GPs that contract with other providers such as dieticians or podiatrists.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

The Dutch health care system enshrines free choice of physicians, but GPs act as strong gatekeepers for access to specialists and hospitals. Except in cases of direct admission through an emergency department, a GP referral is required for specialist care and more complex mental health care.

Hospital Care

For a population of 17 million, there are 120 hospitals, organized into 79 hospital systems. Of these 79 systems, 8 are academic medical centers. All hospitals are not for profit. Hospitals run themselves; they are free to expand or close units as they see fit. Capital costs are folded into the payments from insurers (DBCs).

As in most other countries, utilization of hospitals in the Netherlands is declining. From 2002 to 2015 the total number of hospital beds fell from roughly 48,000 to just under 41,000. About 33,000 beds are in general hospitals, and just over 7,500 beds are in university hospitals. With 3.6 hospital beds per 1,000 people, the Netherlands is about average in terms of hospital beds for the OECD, but it has more beds than the United States (2.6 per 1,000 people). Similarly, the number of overnight admissions has declined as well, as has the average length of stay, from 7.8 days in 2002 to 5.2 days in 2012. Just over half of hospitalizations are one-day admissions. There is still room to shrink hospital capacity. Acute care bed occupancy rates are under 50%—even lower than the United States, where it is about 62%. In addition, as of 2018, there were 134 hospital-affiliated outpatient clinics to deliver specialist care.

There are 2 ways to access hospital care in the Netherlands. When a GP provides a patient with a referral to see a specialist in a hospital, the patient typically has free choice of specialist, unless their insurer has selectively contracted. Specialists can see patients both as inpatients and outpatients in hospitals. About 40% of specialists are employed by hospitals, and the remainder are independent contractors, organized through specialist-owned partnerships (MSBs).

Alternatively, patients can be directly admitted through an emergency department. In urgent situations, such as vomiting blood, patients cannot call an ambulance directly. Either patients call an emergency call center (akin to 911 in the United States) or their GP office. The GP or the emergency services can then call an ambulance. Although emergency departments are supposed to be reserved for emergencies that require ambulance transportation, nearly half of presentations to EDs occur without referrals, and just over half of those (25% of all emergency department visits) are ultimately deemed nonemergent.

Upon arrival in an ED, patients first encounter a triage nurse, who can direct patients to a special GP ward, which is typically adjacent to the ED to handle the less acute problems. If a patient insists on being admitted through an ED for a nonurgent condition, their insurer may not cover the care, and the patient may pay a penalty.

There are also roughly 230 private, for-profit independent treatment centers (ZBCs), and these provide selective, nonacute treatments for up to 24 hours. ZBCs can only provide care that is freely negotiated between insurers and providers (i.e., nonemergency care). Almost all ZBCs specialize in same-day procedures, such as orthopedic surgeries and ophthalmological procedures. From a legal and regulatory standpoint, the ZBCs are classified with general hospitals.

Outpatient Primary Care

According to the Dutch government, there are about 12,000 GPs in the Netherlands, representing almost a quarter of all doctors. According to the OECD, an additional 12,500 physicians are nonspecialized or in generalist fields, such as internal medicine. Overall there are 8.8 physician visits per capita per year in the Netherlands, most of which occur in primary care settings.

GPs are self-employed, and over the last decade there has been a significant shift away from solo practice and toward group practice. Today, 28% of GPs work in solo practice, 39% in 2-person practices, and 33% in groups of 2 to 7 physicians. A typical GP panel size is 2,300 patients.

In many countries patients expect to leave a physician’s office visit with some intervention: a prescription, an order for a laboratory test, or an imaging service. Not so in the Netherlands. Dutch GPs have a strong professional ethos to be efficient, intervene less, and not overtreat. As one health policy expert described it: “[Primary care] is a strong profession. They are well organized. You know, our foreign students always complain, they say, ‘When I go to my GP, I expect to get some drug or referral, but instead he says, ‘Well, go home. If you’re still ill in 2 days, come back. Most diseases just disappear.’”

Since 2012, nurse practitioners are allowed to prescribe medications within their area of expertise. Dutch GPs use and employ nurse practitioners extensively, and these nurses have significant autonomy.

Using a personal story, one professor vividly illustrates how the Dutch delivery system works and the important role of nurses in primary care:

GP care is very well developed, and patients are quite satisfied with their GP. For example, I had this nasty cut on my finger. It had to be stitched and things like that. It was on a Sunday evening. I went to the out-of-hour cooperative of GPs, which is, by the way, next to the ER of the hospital. So, if it is too complex, you will move next door. But there is a GP and nurses at the cooperative. GP comes, stitches in, and he says, come back to your own GP in a week.

Last Monday I went to my GP. In a lot of countries, probably a specialized doctor is going to remove stitches. In this case it’s a practice secretary [a nurse with secondary vocational training]. He removed the stitches and said, ‘It looks good.’ That’s it.

GPs are responsible for providing mild mental health care, such as for situational depression. Consequently, over 80% of GP practices employ a mental health nurse.

Dutch GPs provide extensive after-hours care—nights and all weekends. Typically this care is not provided by the patient’s GP office but through an organized system of GP cooperatives. About 120 primary care cooperatives, each with 50 to 250 physicians, serve the entire Dutch population. These cooperatives follow a nationally uniform model. They use telephone triage, typically performed by nurses, to decide whether a patient needs an on-site consultation, phone consultation, or home visit. The cooperatives are accessible through regional phone numbers. These cooperatives have reduced the use of emergency departments, especially given recent integration with local hospital emergency departments. Physicians who participate are paid hourly for after-hours care.

Specialist Care

There are 33,000 specialists, representing over half of all Dutch physicians. All Dutch medical specialists are based at hospitals or institutions. Therefore, most specialist care is provided in hospital settings either as inpatient or outpatient offices. Recently, some specialist care has moved toward the for-profit ZBCs.

In order to see a specialist, patients must get a referral from a GP, and at times specialists complain about a lack of referrals. Without a referral, insurers only pay 75% of the average national fee to out-of-network providers. Although it is technically possible to see a specialist without a referral, having a patient walk in and see a specialist without going through a GP is essentially unheard of. Many physicians will not see patients without a referral because of the added administrative burden. Once a patient receives a referral to see a specialist, the specialist has the ability to refer to other physicians freely. As with many countries, coordination of chronic care becomes unorganized when specialists refer to each other. However, GPs have generally proven capable of managing specialist care plans for patients with multiple comorbidities.

The Dutch system has successfully cut down on waiting times for specialists over the last decade. Since 2009, Dutch hospitals and specialists have been subject to new regulations governing wait times. The Dutch Healthcare Authority sets target wait times for consultations, diagnoses, and other services. Physicians and hospitals are obliged to publish wait times. In 2009, nearly a quarter of outpatient consultations, treatments, and diagnoses exceeded national standards. By 2014, the data showed that fewer than 15% of care instances exceeded target wait times.

Care Groups for Chronic Conditions

Since 2010, regional care groups that receive bundled payments from insurers have organized care for patients with specific chronic conditions, such as diabetes and COPD. One much-cited example is the diabetes care group, Diabeter. It was established in 2006 and acquired by Medtronics in 2015 as part of the company’s strategy to make inroads in value-based care. The Diabeter model includes a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, dieticians, psychologists, and an administrator who are collectively responsible for a group of diabetic patients. Diabeter’s approach is focused on education to promote self-management; continuous monitoring with digital technology, such as wireless insulin pumps and glucose monitors; and wrap-around services to prevent hospital utilization. A care coordinator organizes all care for the patient. Patients and families are educated about self-management, linked electronically—email and Skype—to the clinic, and have team visits on average 4 times per year. Real-time data from patients’ insulin pumps and glucose monitors as well as data on complications, hospitalizations, quality of life, and psychosocial outcomes are regularly collected and analyzed. The clinic’s percentage of children with HbA1c less than 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) is 56%, compared to the national average of 31%. It also has a very low rate of hospitalizations—about 3%—compared to a national average of 8%. In 2017, the clinic network received the Value-Based Healthcare Prize from the Value-Based Healthcare Center of Europe. Diabeter has 2,000 attributed patients in 5 locations across the Netherlands.

Mental Health

Like most countries, the Netherlands has shifted from institution-based mental health care toward community-based care. Since 2010, the number of mental health contacts per 1,000 patients in primary care settings has almost doubled. While the number of integrated mental health institutions has remained steady at about 30, the number of general mental hospitals decreased from 12 to 2 between 2000 and 2014.

Mental health service delivery is divided into 3 levels. The first level of mental health care occurs in the GP’s office. This care is initially managed by a mental health practice nurse who works in the GP’s office. If the nurse and GP suspect that the patient suffers from a more severe mental condition, such as bipolar disorder or difficult-to-treat depression, they refer the patient to the 2nd level of care, which is short-term mental care provided by psychologists and psychiatrists in hospital-outpatient settings. The 3rd level of care is for even more severe cases requiring specialist care for complex conditions and may include inpatient care. If prolonged inpatient care is necessary, it is provided at specialized mental health institutions and financed through long-term care mechanisms.

Long-Term Care

Because of an aging population and overreliance on institutionalization, long-term care costs have been rising rapidly. Prior to the 2015 reforms, nearly 7% of the Dutch population lived in residential care facilities, such as nursing homes. Nearly 450 residential care companies provided care in about 2,000 facilities. Subsequently, policies have encouraged deinstitutionalization of long-term care. While 24/7 long-term care is financed and administered federally, municipalities are financially and administratively responsible for the organization of social support services and at-home custodial care, such as cooking and light house work, in order to keep people living in their homes and communities. These social supports are paid for through the Social Support Act and are fully organized by municipalities. If seniors living at home need some home-based nursing care, those services are organized by private health insurers through the Health Insurance Act.

The central government is responsible for 24-hour home health care and institutional care. To do this, individual insurers receive a license from the government to manage regional care offices called Zorgkantoors, which coordinate 24-hour home-based or institutional long-term care in cooperation with municipalities and negotiate contracts with long-term care providers.

To receive long-term support, a senior or family member must contact the government’s Care Assessment Agency (CIZ), either directly or through a doctor. The CIZ determines the person’s care profile and informs the regional care office (the Zorgkantoor) if the person qualifies for care under the Long-Term Care Act. Individuals can also choose to be allocated a personal budget to purchase and coordinate their own long-term care independently.

There are some social disparities in long-term care. As one expert put it: “It depends on how much information you give them. In day-to-day practice, it is not a free choice.… For people at a higher income it is easier for them to organize it themselves.” Personal budgets used to be a source of considerable fraud, as they were paid directly to patients. Since 2015, budgets have been deposited into the SVB, which can be drawn down by beneficiaries.

Public Health and Preventive Medicine

The central government sets overall goals for public health, but municipalities are responsible for the actual public health activities. Municipalities provide vaccinations and preventive care services in schools. Municipalities also can launch campaigns for preventive screening for cancer as well as community mental health initiatives. Five regional screening organizations manage population-based screening programs for breast and colon cancer. Although regional and local offices are responsible for promoting and coordinating public health programs, the actual care occurs in GP offices. For example, most influenza vaccines and cervical cancer screenings occur in GP offices.

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

The Dutch pharmaceutical market is relatively small in both absolute and relative terms. In 2017, according to the Dutch government, retail pharmaceutical sales were only $6.4 billion USD (€5.7 billion), accounting for only 7.6% of health care–specific spending. In reality, the level of spending on pharmaceuticals is likely higher because many expensive medications, such as new targeted cancer drugs, are considered part of hospital spending and not broken out in the statistics. Regardless, prescription drug spending as a share of overall health care spending is much smaller than the 14% spent in Germany and Australia or the nearly 17% in the United States. According to the OECD, on a per capita basis, in 2017 the Netherlands spent $410 USD (€360) on retail pharmaceuticals, less than Germany ($780 USD, or €686), France ($662 USD, or €582), or Switzerland ($1,080 USD, or €951) and much lower than the nearly $1,200 USD per capita spent in the United States. This places the Netherlands near the bottom of the OECD in terms of per capita spending. Approximately 68% of pharmaceutical spending is covered by compulsory health insurance, 31% is out of pocket, and 1% is financed by voluntary supplementary health insurance.

Market Access, Coverage Determination, and Price Setting

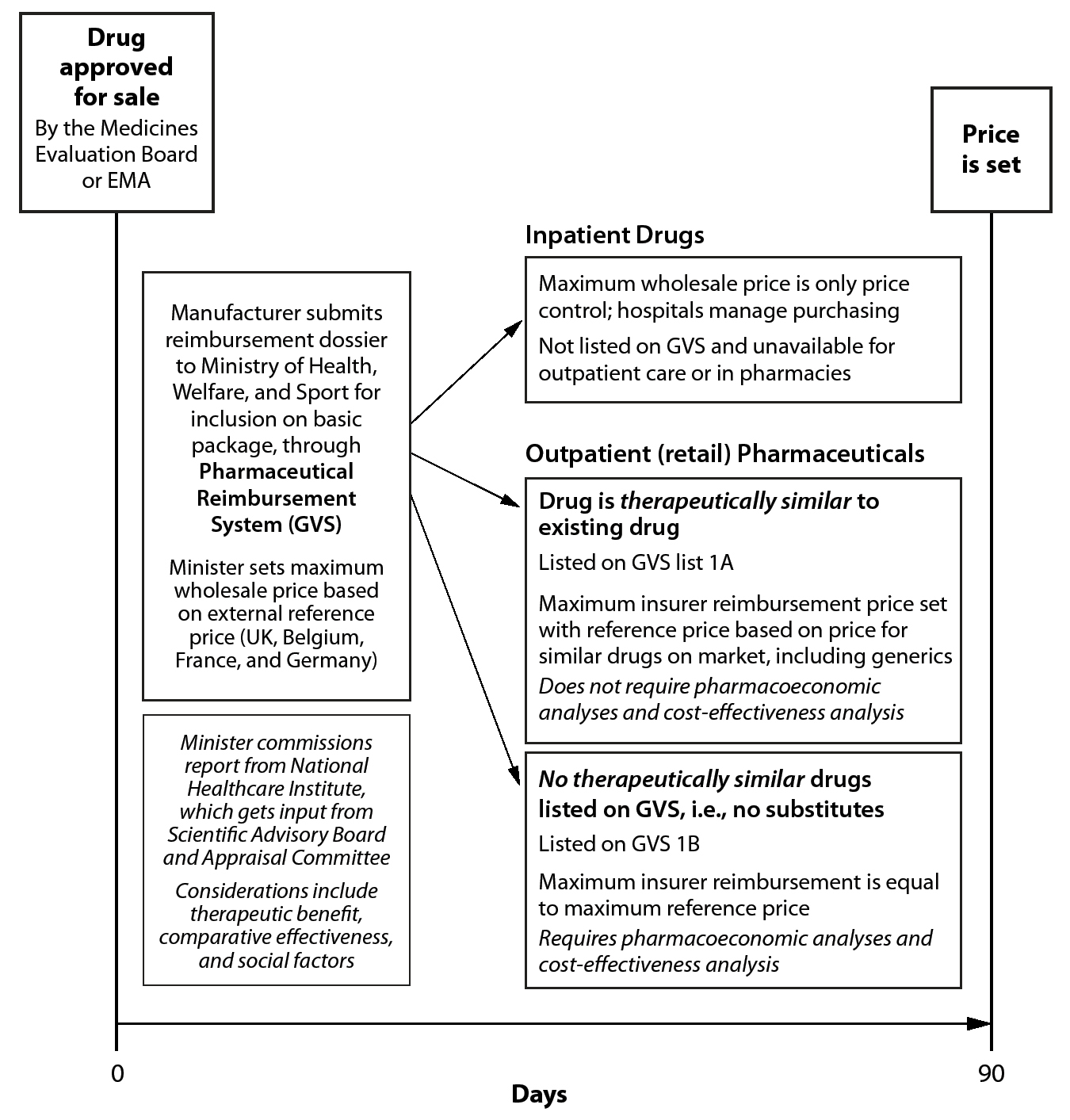

The first step to get insurers in the Netherlands to cover newly approved drugs is marketing approval based on European Union regulation and domestic laws, specifically the Medicines Act and Pharmaceutical Prices Law. All new drugs must be registered with and authorized for sale by the Medicines Evaluation Board, which is the Dutch analog of the US Food and Drug Administration. Market authorization can also occur through the European Medicines Agency authorization procedure. However, approval by the Medicines Evaluation Board does not mean that insurers will pay for a drug; it simply means the manufacturer is legally allowed to sell the drug in the Netherlands.

After receiving approval from the Medicines Evaluation board, the drug manufacturer must submit a dossier to the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport in order for the drug to be listed on the Pharmaceutical Reimbursement System (GVS). Within 90 days of receiving the application from the manufacturer, the Ministry is required to set a maximum wholesale price to distributors. The maximum price is set using an international reference price calculated from the average price of the same drug or a similar product in neighboring countries: Belgium, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The Ministry can use drugs with the same active ingredient, including generics. The maximum price can only be calculated if at least 2 of the comparison countries have a comparable drug on the market.

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (Netherlands)

Within 90 days, the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport must also determine whether the new drug may be included in the basic insurance package. Drugs in the basic insurance package must be reimbursed by health insurers for use in outpatient settings—that is, in sales at retail pharmacies or from a dispensing GP. There are 2 drug lists in the GVS. List 1A is composed of drugs that have interchangeable therapeutic equivalents already available in the Netherlands, such as statins for lowering cholesterol. List 1B is composed of drugs without substitutes—that is, they have significant added therapeutic benefits to be unique. Placement on the GVS may carry additional restrictions on prescribing and use, such as limiting targeted cancer treatments to specific subpopulations based on genetic mutations in tumors and disease progression.

The maximum reimbursement price paid by insurers for drugs on the GVS depends on which list a drug is placed on. In general, the National Health Care Institute assesses the new drug’s medical necessity, clinical effectiveness, cost effectiveness, and side effects. The Scientific Advisory Board assesses the therapeutic benefit and cost effectiveness of the drug, while the Appraisal Committee provides a needs assessment. For list 1A drugs—drugs with an available therapeutic equivalent—the minister sets a maximum reimbursement rate based on the average of prices of all medicines in the group, including generics. Conversely, because there is no equivalent for List 1B drugs, the maximum reimbursement is equivalent to the external reference price for wholesale distributors. Importantly, drugs can be exempt from the required pharmacoeconomic analysis when they are not expected to cost over a set yearly budget threshold and are unlikely to increase national drug costs. This mainly applies to orphan drugs with high prices but small numbers of patients. There is no governmental price setting for over-the-counter drugs.

Individual hospitals establish what drugs they will use and negotiate prices directly with drug manufacturers. These negotiations are limited by the maximum price set by the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. Recently there has been a push for more government involvement in regulating hospital drug prices, especially for high-cost specialty medicines. If the Ministry decides that a new, expensive drug should not be available in hospitals, it can exclude the drug from inpatient settings.

The delineation of reimbursement controls between inpatient (where hospitals are expected to negotiate) and outpatient settings has generated controversies. From 2012 onward, several especially expensive classes of drugs were removed from the GVS and placed onto hospital budgets, causing hospitals to bristle at having to pay. As a compromise, hospitals were compensated for expensive medications and orphan drugs, including many new cancer drugs, growth hormones, and TNF inhibitors such as Humira used for rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, although prescription drug prices and spending appear to be low, the reality is that a significant portion of drug spending has been shifted onto hospital spending.

Over the last decade, the government has attempted to expand access to new, expensive drugs. From 2006 to 2012, the Netherlands experimented with several types of managed entry agreements (MEAs), or conditionally allowed specialist medicines. These MEAs provide temporary coverage contingent on the generation of additional evidence of therapeutic benefit. However, the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport found that even with the MEAs, access to drugs that were ultimately deemed cost effective was not achieved. Consequently, the Dutch are reforming the process.

Prescribing Controls and Bulk Purchasing

Dutch insurance companies also play a role in controlling drug spending. The most important tool is the “preferred medicine” policy, or insurer formularies. Insurers are allowed to select a specific brand of preferred medication from a cluster of pharmaceuticals with the same active ingredients. Pharmacies are obliged to only provide the preferred medication to the insurer’s patients. Alternatively, insurers can set a maximum reimbursement price for a specific active compound. If pharmacists buy a drug for less than the maximum price, they keep the savings. The use of bulk purchasing and competitive bidding has been effective for controlling generic prices.

Although generic substitution is not mandatory in the Netherlands, the Dutch electronic prescribing system automatically substitutes generic for brand-name drugs when they are available. Physicians must medically justify prescribing a brand-name drug when there is a generic alternative available. At the pharmacy level, pharmacy fees are fixed per dispensation, regardless of the drug’s price, obviating an incentive to dispense higher-priced brand-name drugs.

Prices Paid by Patients

Several policies insulate Dutch patients from high out-of-pocket drug costs. First, many high-cost drugs have been shifted to the hospital formulary, and patients have no co-pay for these once they meet their deductible. Second, list 1A drugs are essentially free after the mandatory deductible is met. However, there is still a small problem of surprise costs before deductibles are met because although GP services are exempted from the deductible, prescribed drugs are not. Third, insurers can waive cost sharing for preferred medicines. For drugs on list 1A that are priced above the maximum reimbursement, patients must pay the difference between the reimbursement price and the retail price. However, because over 90% of drugs on list 1A are fully reimbursed, these drugs are typically free to patients. Finally, the Netherlands also has reduced taxes on drugs. The standard VAT rate is 21%, but for drugs the VAT is just 9%.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

According to the OECD, there are roughly 60,000 practicing Dutch physicians, including 27,500 generalists—such as GPs, pediatricians, and internists—and 33,800 specialists. The Netherlands has just over 3.5 practicing physicians per 1,000 people, an average rate among European countries. Because of its relatively small size, highly urban population, and high population density, the Netherlands does not have a severe rural-urban maldistribution of physicians. Only the remote and sparsely populated northern islands have a physician shortage. In addition, nearly all citizens live within a 25-minute drive to a hospital, and 99% of the population can reach an emergency department within 45 minutes.

Dutch GPs and specialists are compensated fairly well, but they are not as highly paid as US or Swiss doctors. In 2016, the average salary of GPs was $123,000 USD (€108,000), and for specialists the average salary was $190,000 USD (€168,000). The range of salaries for physicians is fairly narrow, as one researcher noted,

I believe a specialist salary goes from 180,000 to 240,000 or something.… It is a different culture. I know that I was [in the United States], and there was some orthopedic surgeon who earned $4.2 million just from Medicare.… In the Netherlands if you would earn $4.2 million, you will be shamed.… Everybody in the Netherlands would say, “It’s our money! What’s the guy doing?”

Medical education is provided at 8 domestic medical schools. Initial undergraduate medical education lasts 6 years. The first 4 years consist of an undergraduate preclinical bachelor’s program, and the final 2 years focus on clinical training, conferring a doctorate of medicine. Medical education is subsidized. The mandatory annual fee is just $2,400 USD per year (€2,083) as of 2019.

Recently medical education has shifted toward competence-based training in which promotion to the next stage is not dependent upon time but upon mastering a set of skills. Graduation times, residency start dates, and completion have become nonstandardized. Students complete their training on an individualized timeline.

Most physicians take a one-year internship before starting postgraduate (residency) training. The College of Medical Specialists (CGS) regulates specialty training. Training to become a GP lasts 3 years, while training for specialties ranges from 4 to 6 years. There are work-hour limits. Dutch residents may not work more than 60 hours per week, with a maximum shift of 12 hours. The government pays hospitals to cover residents’ salaries and training.

Nurses

There are approximately 200,000 practicing nurses in the Netherlands, or 10.5 per 1,000 people, fewer than in Germany but more than the United States. Like many developed countries, the Netherlands is dealing with shortages, particularly for some specialist services. The average salary of nurses is roughly $62,000 USD (€55,000), about 17% higher than the average national wage.

The Netherlands has a high number of advance practice nurse practitioners (NPs). An ever-larger number of tasks, particularly mental health and primary care, have shifted to nurses. In the Netherlands advance practice NPs have a large scope of practice and prescribing authority, as one researcher noted,

I think the strong point is the increasingly good and independent position of nurses, which is, for instance, compared to Germany, really a world of difference. In the Netherlands nurses are much more an independent profession. We have nurse specialists who have advanced degrees and who also have rights of prescription in certain areas. That is something for which in Germany you couldn’t even think of it.

Nurses are also important for long-term care as coordinators between municipalities and patients. The same researcher went on to explain, “District nurses work in teams [for long-term care], and they are the ones with a bachelor in nursing and a one-year extra education in district in nursing. The district nurse is again allowed to assess the patient and decide how [many services and what kinds] the patient needs. Most home health care is provided by certified nurse assistants, who only require 3 years of training.

Dental Care

There are 8,500 dentists in the Netherlands, or 0.5 per 1,000 people. All dentists are private. For children under 18 dental care is covered under the basic benefits package. For adults, dental care, except oral surgery, is not covered. Most insurers offer partial dental insurance under the private supplementary insurance, but a significant amount of dental care is paid out of pocket. Consequently, some of the largest socioeconomic disparities in the Netherlands relate to the utilization of dental care.

CHALLENGES

The Dutch health care system is in the middle on cost and is efficient at providing high-quality care. As one observer succinctly noted, “Most of the parties dealing with the system are fairly happy with it.… The grand design of the system is workable.” Indeed, there are many virtues of the Dutch system. The Netherlands has achieved universal coverage. The government covers universal health care for children at no cost to families, regardless of household income or number of children. The private health insurance system is stable through a well-managed system of compulsory, community-rated premiums and an effective risk adjustment program that redistributes pooled funds to plans based on expected costs. The governance of the risk adjustment system and sophisticated academic modeling appear to prevent gaming by insurers, thereby preventing adverse consequences for higher-risk patients.

The Dutch system also does a fairly good job of steering patients toward higher-touch, lower-cost care in GP settings. Task shifting has been well instituted, with nurse practitioners providing significant primary care and care for mild mental health conditions. Consequently, the use of hospitals and specialists for chronic and routine care is not high. Finally, like the Germans, the Dutch have a mandatory, tax-financed national insurance program for long-term care that can be provided at home or in institutional settings. Providers are well compensated, and the quality of care delivered is high.

It should also be said that the Dutch have a way of getting through thorny systemic problems. There is a national ethos to make things work and prevent crises. Hospitals, physicians, and insurers are willing to work together to develop patchwork fixes to systemic problems. Negotiations over prices and utilization tend not to be aggressive and confrontational. This muddling-through ethos prevents crises from developing but can also postpone addressing problems and allowing some large flaws to fester without comprehensive reform. For example, by moving specific high-cost drugs from outpatient to inpatient settings and compensating hospitals with specific add-on payments from insurers, hospitals, insurers, and the government have routinely changed how expensive pharmaceuticals are paid for in order to keep out-of-pocket costs low at the point of service.

Nevertheless, there are 3 important long-term challenges for the Netherlands. The first is cost and cost growth. The Dutch are attuned to cost control and instituted the current system of managed competition in response to growing cost problems. Nevertheless, there is a sense that managed competition has not restrained costs effectively. Insurers’ negotiations with hospitals have not reduced costs, and attempts at lowering cost increases of drugs have not worked well. Although cost growth is not excessive in the Netherlands, many observers think the current level is high, and it will require vigilance to keep growth low.

The 2nd and related challenge concerns long-term care. Unlike most countries, the Netherlands created a dedicated, mandatory tax system financing long-term care. Even as it provides funds, this benefit is seen as a major factor driving up health care expenditures. As a former politician put it:

The first and biggest problem is cost. The rate of health care expenditures tends to grow at least twice as fast as the rate of national income. We know that if you look deeper into the Dutch system, that we do spend a lot more on long-term care than other countries.… You can’t explain the difference by demography.

To address the long-term cost problem, the government has tried to transition from an “open ended entitlement” to one in which municipalities receive a budget and oversee the provision of long-term care. As the former politician explained, the transition has been politically problematic, and policy has veered back and forth:

We talk about the elderly, you talk about the handicapped, and basically if everybody says more money should go in to it… the previous government made a serious cut in the expenditure on long-term care, basically by decentralizing a lot of it… and the next government in power basically put the money back into the system, and everything that was being cut 5 years ago is now being put back in. I see it as a waste, but you know, who dares be a politician that says you shouldn’t put [more] money towards the elderly?

Complicating these changes has been the fact that many municipalities lack the technical capacity to manage long-term care. One policy analyst noted just how daunting the task was for small local governments: “We have way too many municipalities—400 or something. There is no knowledge, and nobody understands what they are doing.” In response, there is a trend toward regional organizations rather than local ones to manage long-term care. Whether this can help address the problem is unclear.

Another problem is that although municipalities have responsibility for long-term care, they do not have authority over home health nursing services; these services are provided under the Health Insurance Act. This creates the perverse incentive for municipalities to shift care to home health nursing when possible. Simultaneously, insurers want to shift more care to social supports financed by the municipalities. This financing arrangement undermines coordination and seems to lead to escalating costs rather than efficiency.

Finally, there is an underlying social challenge posed by long-term care that inhibits solving the problem. The welfare-state model has long been ingrained into the Dutch culture. The state should provide for the elderly. As one Dutch observer noted, “In the Netherlands children are not financially responsible for their parents—that makes a difference.… From the 1950s onward the responsibility was taken from children for their old parents and taken over by the state.” The recent reforms aim to shift responsibility for care of the aged from the state to local governments and the family. Many Dutch experts suggested that trying to change from a state-based delivery model to one that placed responsibility on municipalities and families met with a lot of inaction, slow walking, and passive resistance.

A 3rd challenge is the Dutch desire to have both managed competition and cooperation. The tension between the 2 often inhibits solving problems of the health system. For example, managed competition should work in part because of selective contracting with highly efficient physicians and hospitals. But selective contracting contravenes cooperation and, thus, has not reached any significant threshold. As a researcher put it, “We introduced this managed competition, but next to that we have this municipal system, and the municipal system is much more based on cooperation. The managed competition is based on competition and not based on cooperation.” The Netherlands has generally reverted to a reliance on large-scale national agreements such as the Health Care Budget set by the minister as the main tools of cost control. The Health Care Budget may run counter to the principles of managed competition, but ultimately it has been necessary to keeping the system affordable.

The Dutch government, insurers, and providers have all been able to make do under what is essentially a compromise system between neoliberal ideals of competition and a historical welfare-state–based approach. Because the overall health system generally works well, there is little appetite for additional large-scale health reform. As a former politician put it, “Everybody is dead scared of losing 5 years to changing laws and in augmenting your system. They would rather try to work within the system that we have.”