CHAPTER TEN

TAIWAN

“We go to the hospital like it’s the shopping mall,” said Phoebe Chi, CEO of the Taiwan Association of Cancer Patients. Indeed, the Taiwanese treat medicine much like a low-cost consumer good. Patients can go to any doctor and any hospital in the country. They can even order blood tests and an MRI scan themselves and have the system pay for them.

The inevitable corollary is that the system frequently provides impersonal and austere care. Underpaid physicians see up to 90 patients a day, all for a few minutes. Hospitals are decorated and furnished more like graduate housing, and families are expected to provide custodial care for their relatives who are hospitalized.

But care is usually timely. And the system has an exemplary electronic health card that makes payment seamless and gives government officials real-time health data. Overall, national health care costs are about half of those in other systems—and a third of the US expenditures—making Taiwan a country with an enviable health system.

HISTORY

Universal health care is a relative novelty in Taiwan.

For most of the 20th century only a fraction of the population had any health insurance. They got it through a handful of smaller social insurance funds tied to specific sectors of the economy, such as civil service and farming. As recently as the early 1990s, nearly half the Taiwanese population still had no health insurance. When they needed medical care, they had to rely on charity care, drain their savings, or go without needed treatment—which sometimes meant they would “just accept it [and] go home to die,” as Lee Po-Chang, a kidney transplant surgeon who later became director-general for the national health insurance system, put it.

In the early 1990s Taiwan was in the midst of a dramatic upheaval galvanized by democratic ambitions and economic growth. Since declaring the Republic’s independence in 1949, the nationalists had ruled through a kind of martial law, suppressing political dissent. But by the 1980s there were growing demands for more democratic freedoms. Simultaneously, there was tremendous economic growth. The economy was expanding at 10% annually, and the middle class increased substantially. These 2 trends fueled public expectations for more public political engagement and expanded government services. At the top of the list of demands was better, more affordable health care.

Nationalist leaders in the government were determined to act, in no small part because they risked losing support to an opposition party whose platform included universal health coverage. Officials studied other countries’ health care systems and, based on that research, constructed one that would work best for Taiwan. As officials later told American journalist T. R. Reid, in designing their health care system, the Taiwanese consciously followed an old Chinese proverb: “To find your way in the fog, follow the tracks of the oxcart ahead.”

Among the experts they tapped for advice was Bill Hsiao, a Harvard health economist who led the first planning effort. They also spoke with Uwe Reinhardt and Tsung-Mei Cheng—both Princeton economists—who argued that Taiwan was a natural candidate for a single-payer scheme: the population was not too big, and the transformation would not require dismantling a lot of existing insurance infrastructure. Above all, a single-payer system would embody the Taiwanese government’s 2 most important values: equality and efficiency. The idea came to be known in Taiwan as a single-pipe system, a phrase Reinhardt had used. The planning committees embraced it, recommending that Taiwan collapse the country’s existing social insurance plans into a single, tax-financed government health insurance program.

Taiwan’s lawmakers took up the idea, igniting a political debate in which the stakeholders raised familiar, predictable objections. Physicians worried about the effects on their incomes. The sickness funds lobbied to keep operating. Employers were unhappy about the payroll taxes to finance the plan. But the bipartisan consensus for reform—and the obvious need for it, given the large number of uninsured—meant advocates for the scheme had sufficient political support to overcome the opposition. On July 19, 1994, the new National Health Insurance (NHI) system was enacted. Less than one year later, on March 1, 1995, it commenced operation.

Taiwan could pull off the quick transition in part because NHI adopted many of the old social insurance fund operations. Reimbursement worked in the same way, except that now it was a central government agency, not the separate sickness funds, processing payments. To ensure that everyone who already had insurance felt their new coverage was equal to or better than what they previously had, the government made sure that the benefits package of the most generous fund, which had covered civil servants, was the baseline, and then they added to it. This assuaged worries that a single-payer system would be worse than what existed before.

But NHI did not include any meaningful efforts at cost control.

Within a few years expenditures exceeded revenue, prompting the government to introduce a series of modifications that quickly brought the NHI’s budget back into balance and eventually led to surpluses. These reforms included legislation that brought new revenue into the NHI by increasing the existing payroll taxes and creating new taxes on income and tobacco. The government also established a global budget, introduced DRG payment for some hospital services, applied more rigorous cost-effectiveness analyses to drug prices, and experimented with pay-for-performance reimbursement schemes.

In 2006, Taiwan created its first comprehensive long-term care program. It operated wholly outside the NHI and in a wholly different way, providing income-linked assistance and with financing from general tax revenues. The program was a partial solution at best because it excluded many people and offered low benefits. In 2016, following several years of debate, the government proposed to transform the long-term care program into a social system that would operate in parallel with the NHI.

But right before the transition was supposed to take place, political control of the government changed with an election. The new regime abandoned the reform plan, which it had opposed, and chose instead to modify the existing long-term care program. The updated program offered more assistance to more people, but it still left a large swath of the population relying on their personal resources and charity for long-term care needs.

Even so, few people dispute that the NHI has largely achieved its primary goals of equity and efficiency. Taiwan has universal coverage, and its per capita spending is low by international standards. But Taiwan’s system and its performance have not received significant international attention, largely because of its unusual political status. As Hsiao observed, statistics on Taiwan’s health performance are not part of the usual comparative databases, such as the one maintained by the OECD, because of Taiwan’s disputed status as a nation and its conflict with China. This limits study of the system.

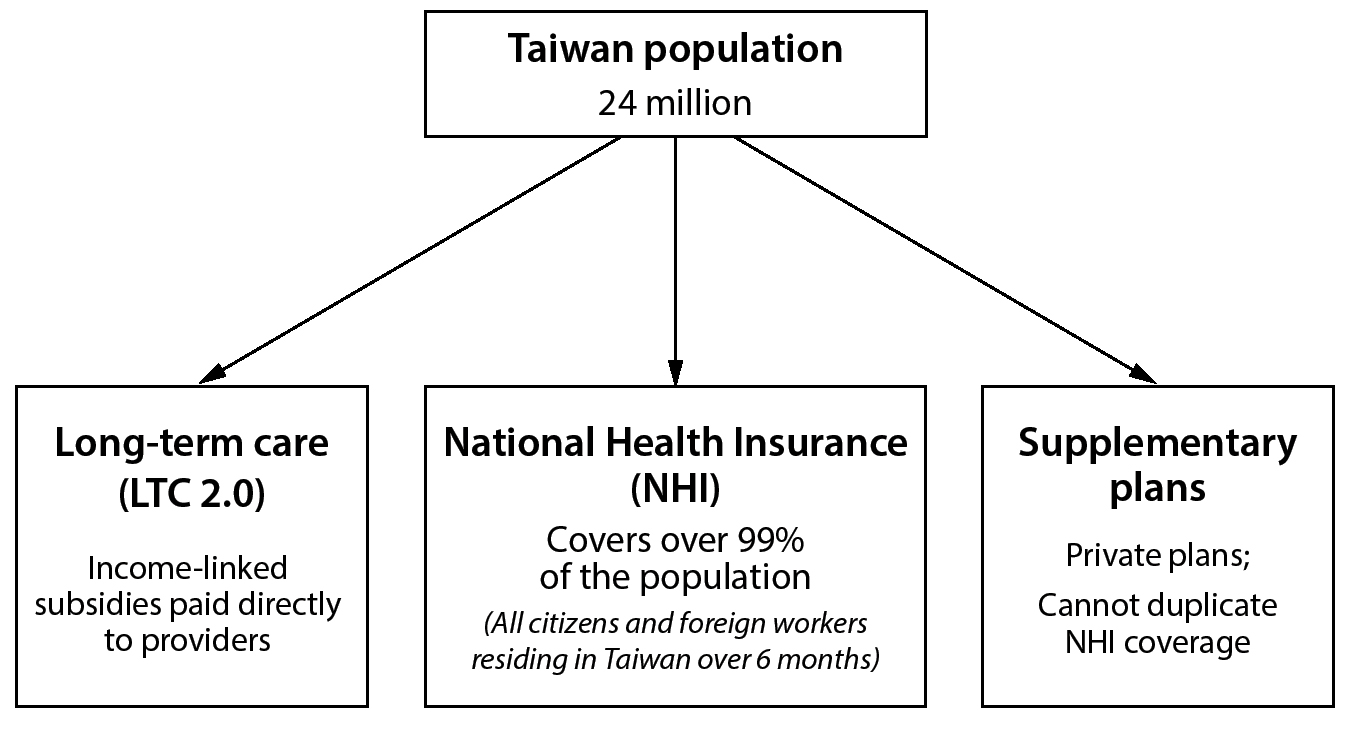

COVERAGE

Taiwan has a population of just under 24 million. More than 99% of its residents have insurance through the government’s comprehensive NHI system. Private coverage exists, but by law it cannot cover services the NHI provides. Private supplemental insurance pays cash directly to beneficiaries, who can then use the money to get amenities like private beds, fill in the NHI’s small coverage gaps, or for some other purpose.

Public Insurance

NHI is administered by the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA), which is part of Taiwan’s Ministry for Health and Welfare. Enrollment is automatic. It happens at birth or, for those who arrive in the country and do not sign up on their own, at the first encounter with a health care provider. It covers all citizens as well as all foreigners who reside in the country for more than 6 months.

The NHI benefits package is comprehensive. It includes inpatient and outpatient care, prescription drugs, and mental health care, but unusually it also covers dental and vision care for both children and adults. Also unusually, NHI pays for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) as long as the government licenses the providers and Taiwan’s food and drug administration approves the medications.

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (Taiwan)

There are some services the NHI does not cover, though. These uncovered services are a bit unusual by developed country standards; they include birth control, abortion, smoking cessation therapy, and drug addiction therapy. It also does not pay for certain devices or equipment such as hearing aids, artificial eyes, or wheelchairs. The NHI website offers an explanation for these exclusions: they are “not required to actually treat the patient.”

The architects of NHI believed that cost sharing was important to provide some disincentives for seeking unnecessary care. As the NHI official website explains, “The main reason for requiring a co-payment is to remind the insured that medical resources are used to help people who are ill or injured and should not be wasted under any circumstance.” For that reason, NHI links inpatient and outpatient care to cost sharing. But even these cost-sharing amounts are low—at a maximum of about $18 USD (550 NTD) for emergency care.

Private Coverage

Although insurance companies cannot sell insurance that duplicates, even in part, the coverage NHI provides, they can—and do—sell supplemental health insurance policies. These are old-style indemnity policies in which patients just get cash when they file claims. Some of these indemnity policies are diagnosis specific—they pay only if the policyholder gets cancer, for example. Others pay whenever the policyholder incurs a major medical expense authorized by a licensed provider.

Patients can use the money to replace lost wages, cover out-of-pocket health expenses, help pay for new drugs or treatments that NHI has not provided, or pay for amenities like private hospital rooms. Patients can also use the cash benefits to pay for services from the few physicians who do not accept NHI reimbursement. They can also use the money to pay for special VIP clinics, which offer extra attention from top doctors, that some hospitals operate.

There are no official data on these plans, so it is difficult to say definitively how many people have them or how patients use the money. Anecdotal evidence suggests they are most popular with middle-class professionals and small business owners as well as the better-paid foreign workers. Individuals frequently take out multiple policies at a time because many pay out only small sums. Calculations by one industry source in Taiwan suggest that in 2019 the number of active private health policies was actually 3 times larger than the population. But that figure is a bit misleading—only a fraction of the population has the policies. Nobody really knows how big that fraction is.

Long-Term Care

Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare plays an important role in long-term care—sometimes as the provider of services, more commonly as its financier. But the Ministry performs these functions through a set of programs that are largely separate from the NHI and that function in a very different manner.

In 2017, the Taiwanese government launched its long-term care plan, Long Term Care 2.0 (LTC 2.0). Its explicit goal is to help seniors age in place. It subsidizes the long-term care needs of people with disabilities or dementia as well as the frail elderly. To assess who is eligible for benefits, the Ministry uses a series of internationally recognized tests, such as the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures index for frailty and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale.

LTC 2.0 subsidies go directly to the providers of long-term care, not the patients. LTC 2.0 also underwrites the construction and operation of a nationwide network of care centers. These centers employ counselors who can help families with needs assessments and care arrangements. In addition, the centers provide activities and services for people who live at home with long-term care needs. For example, they offer memory classes for seniors with age-related cognitive decline.

Although LTC 2.0 subsidies are income linked, they are not generous. Families still end up paying a significant fraction—sometimes the majority—of long-term care costs on their own. One reason this arrangement persists is the widespread belief that helping the disabled and elderly with their daily needs, unlike the treatment of illness and injury, is primarily the responsibility of the patient’s family.

A common solution to this cost problem is for families to hire foreign care workers, whom the government has long allowed to work in Taiwan on a temporary basis. Paradoxically, these foreign care workers are required to sign up for NHI if they are in Taiwan for more than 6 months, but they are not eligible for LTC 2.0 benefits themselves.

FINANCING

Taiwan’s government does not break down total health spending in ways directly comparable to the national figures that the OECD uses. Based on the Ministry’s official statistics, in 2018 total health care spending in Taiwan was low: $34.6 billion USD (1,100 billion NTD)—or roughly $1,500 per capita USD (47,500 NTD)—accounting for 6.3% of GDP. The total budget for the NHI was just under $20 billion USD (approximately 600 billion NTD), or less than 4% of GDP. This is approximately $840 USD (26,600 NTD) per capita. The rate of growth was about 3% per year, comparable to other developed countries.

Finally, it is hard to compare official government health cost data to the data from other countries. The estimates may be artificially high because they include out-of-pocket spending for personal items like diapers and vitamins, which are not included in most other countries’ estimates. Conversely, they may be low because there are no reliable data on the costs of private supplemental health insurance.

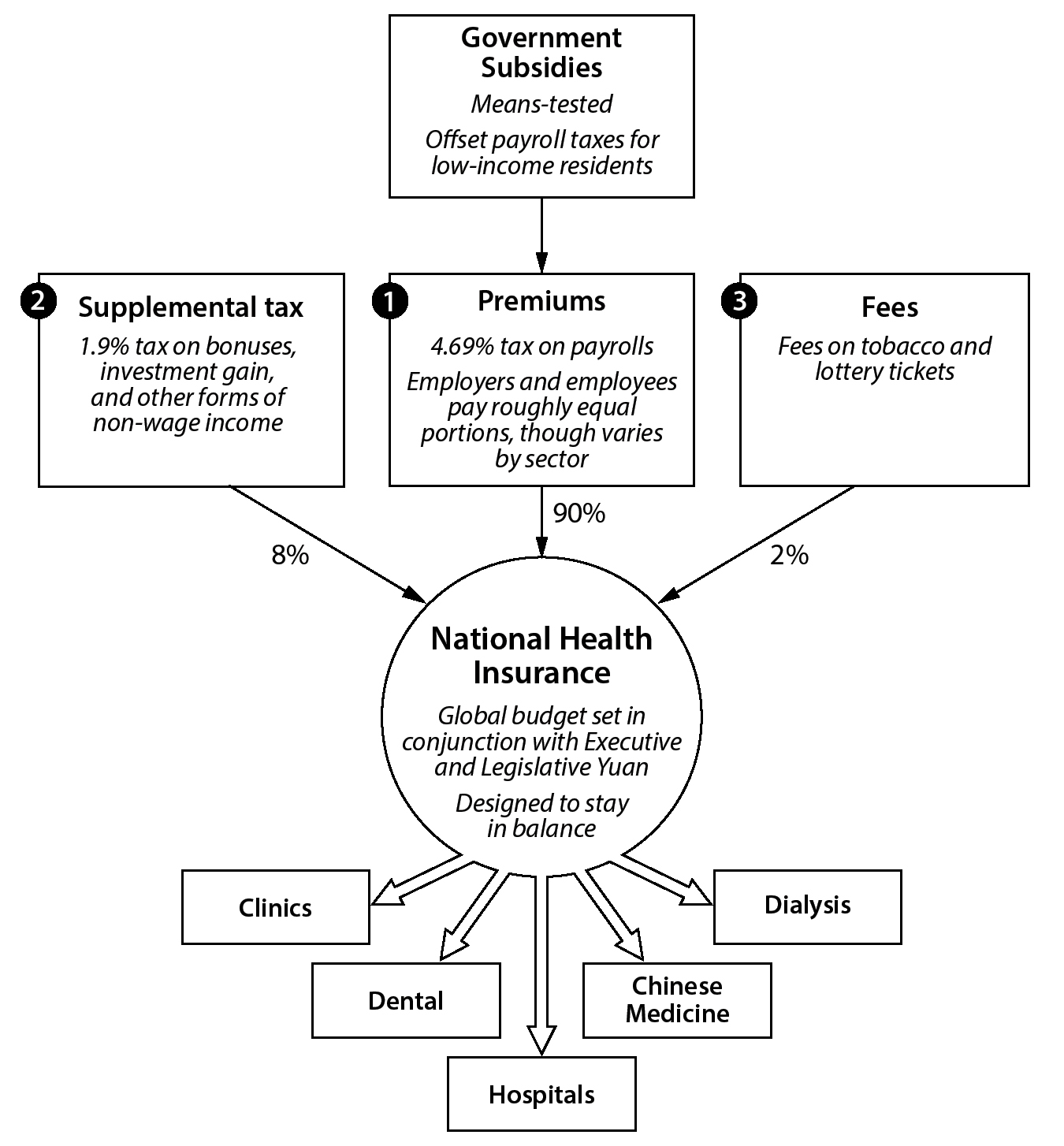

Figure 2. Financing Health Care (Taiwan)

Public Health Insurance

The NHI has 3 main sources of financing: (1) premiums, which come from a combination of payroll taxes and government subsidies; (2) a supplemental tax on nonwage income; and (3) tobacco taxes and lottery fees.

About 90% of NHI funding comes from the premiums, roughly two-thirds of which come directly from the payroll taxes. The total payroll tax rate is 4.69%, with employers and employees paying about half, although the precise percentages depend on the type of employment. For instance, civil servants contribute less than private-sector employees. The typical family of 4 pays roughly $100 USD (3,200 NTD) in monthly payroll taxes, equivalent to about 2% of household income. In Taiwan these payroll taxes are considered and explicitly referred to as NHI premiums.

The government has taken several steps to mitigate the impact of these payroll taxes. The biggest step is subsidies for low-income people, people with disabilities, and the unemployed. About 3 million people receive these subsidies, which the government finances with general revenue, and they account for about one-third of total premiums.

About 8% of NHI funding comes from a 1.9% tax on nonwage income, including one-time bonuses, investment gains, and rental income. The final 2% of NHI funding comes from dedicated tobacco and lottery fees.

In 2016, the NHIA in the Ministry for Health and Welfare took another major step to help the poor and others struggling with medical bills. Previously the agency would “lock” electronic medical cards for people who had fallen behind on payroll taxes. Providers use the card to log appointments and file for reimbursement, so this effectively made it impossible for people with outstanding bills to get care until they had paid up—unless a doctor or hospital would see them for free or with off-the-books cash payments. In 2016, the government ended that practice, a step, the NHIA said, that “symbolizes a new level of protection for the human right to receive medical care.”

Even with all of these protections and subsidies in place, some people still end up with unpayable medical bills. To help those people, the Taiwan government offers interest-free loans for the payment of old medical bills. In 2016, it gave out more than 2,000 such loans.

Private Health Insurance

Private insurers sell the supplemental indemnity policies directly to consumers, frequently as an add-on to life or property insurance. They also sell some policies through employers, who can offer it to employees as an optional benefit. Costs vary enormously depending, in part, on the type of insurance and who it covers. Based on anecdotal reports, monthly premiums seem to be less than $200 USD (6,300 NTD).

Global Budgeting

To limit total health care spending, the Ministry of Health and Welfare defines a global health budget each year and adjusts payments to hospitals and physicians quarterly to ensure the budget is not exceeded.

The Ministry spends nearly a full year setting a health care budget, which is the main tool it has for cost control. It examines current health care spending and adjusts it for population growth, inflation, and decisions to cover new drugs or treatments. The Ministry then develops both a high- and low-end request for what the NHI should spend the next year. That proposal goes to the Executive Yuan, Taiwan’s equivalent of the cabinet, for approval. Once the Executive Yuan signs off, the budget goes back to the Ministry, where a 35-member committee—including representatives for hospitals, patient groups, and other stakeholders—finalizes the global budget. The committee determines how much of the global budget goes to each of 5 areas—hospital care, medical clinics, dental care, Traditional Chinese Medicine, and dialysis. Once that is done, the NHIA distributes money to the 6 regional health authorities, which process claims and write checks. The budget also sets aside money for risk adjustment in case the projections prove inaccurate.

Because fee-for-service is the predominant method of reimbursement, there are incentives for providers to perform more services or more expensive services. To ensure such behavior does not lead to exceeding the global budget, the NHIA adjusts how much it pays per service—that is, the price—quarterly to reflect the volume of services. “Under the global budget system,” NHIA Director General Lee Po-Chang explains, “the unit price for all fee schedule items is inversely related to the service volume.”

To illustrate how the system works, Lee cited a hypothetical example in which the government had set the global budget at one point per NT dollar and allocated 1 million NTD overall. If utilization came in higher—say, 1.1 million points’ worth of services—then the NHIA would reduce the point value to 0.909 NTD per point. (That’s the ratio of 1 million:1.1 million.) For a procedure that NHIA paid 1,000 NTD the previous quarter, it would now pay 909 NTD.

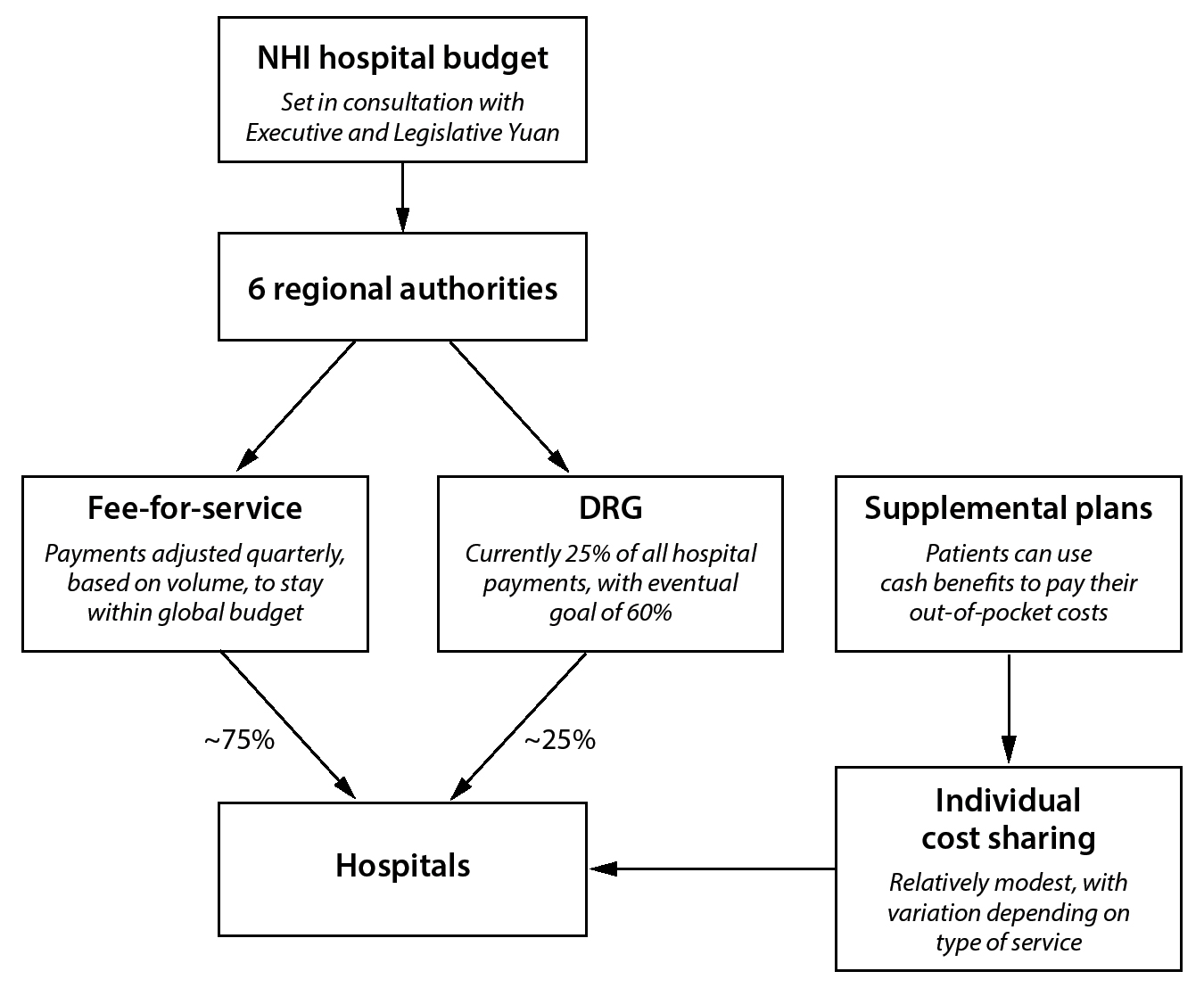

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (Taiwan)

PAYMENT

NHIA distributes money for NHI to 6 regional authorities, which in turn pay hospitals, clinics, and other providers directly. Most payment is fee-for-service.

Payments to Hospitals

Roughly three-fourths of hospital payments are on a fee-for-service basis. The remainder goes through DRG payments, which the NHIA has been introducing gradually. The government’s goal is for DRG payments to account for 60% of all inpatient revenue eventually. The NHI also uses pay-for-performance incentives to encourage better care for several major conditions. As of 2018 more than 50% of patients with asthma and early-stage chronic kidney disease were part of pay-for-performance programs.

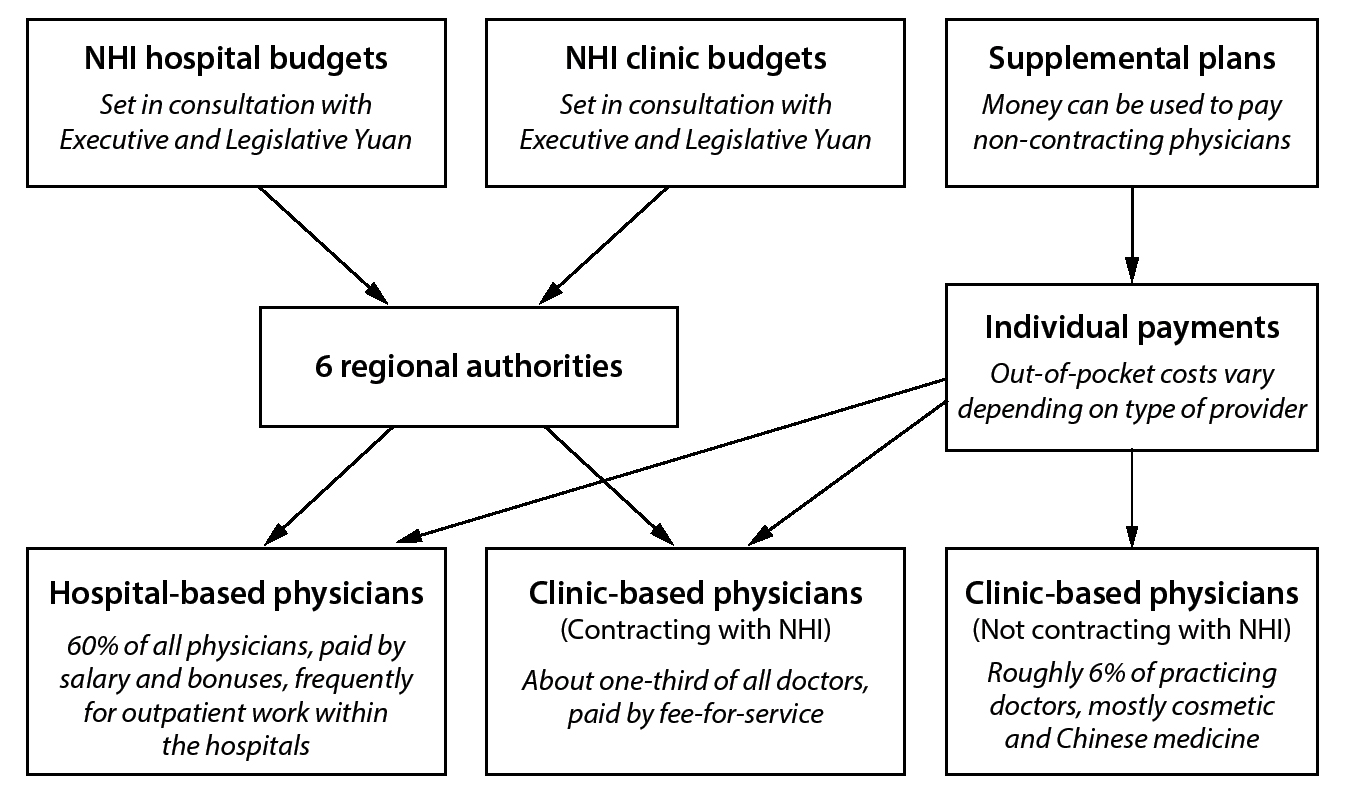

Figure 4. Payment to Physicians (Taiwan)

Payments to Physicians

There is no specific figure on how much physicians are paid.

Physicians and dentists work for hospitals or incorporate themselves into clinics—the equivalent of physician offices. The NHI pays hospitals and clinics for physician and dentist services. Thus, physicians working on their own or in small clinics are paid on a fee-for-service basis, while those working for hospitals can be paid in a variety of ways, including salary and bonus payments. Billing and payment through the fee-for-service system is relatively seamless: clinics and hospitals file claims through the electronic health cards and receive their payments electronically.

Roughly 6% of physicians do not take NHI payments and rely entirely on private payment, operating concierge-style practices for people who can afford them. A significant percentage are cosmetic surgeons and TCM doctors, although exact numbers are not available.

Out-of-Pocket Payments

Reliable and official figures on out-of-pocket spending are not available. But according to one official estimate, provided by the NHI director at the request of an outside scholar, about 12% of health care spending in Taiwan is out of pocket.

Out-of-pocket payments are explicitly meant to remind people that health care services should not be wasted but are meant for the sick and injured. Nevertheless, they are relatively low. A patient admitted to the hospital is directly responsible for 10% of charges for the first month of treatment, 20% of the next month, and 30% for anything beyond that. There are also caps on out-of-pocket inpatient expenses: 6% of average national income per single episode and 10% per year.

Co-pays for outpatient and emergency care are flat fees, which vary depending on the type of institution and whether the patient got a referral. They are generally small and have a maximum of less than $18 USD (550 NTD) for emergency care at the top-tier medical centers.

Another source of out-of-pocket spending is payment for a small group of medical devices, such as heart stents and artificial hips. The NHI reimburses these devices based on the cost of devices it deems less expensive but clinically equivalent. Patients can still get the newer devices but only by paying the price difference.

As in other countries’ systems, NHI has caps, discounts, and waivers for groups the system deems vulnerable. There is zero cost sharing for patients with cancer and 29 other catastrophic illnesses as well as low-income households, veterans, and children under age 3. NHI waives prescription co-pays for treatment of diabetes, high blood pressure, and roughly 100 other chronic diseases. It waives physical therapy co-pays for certain intense therapies. It also reduces co-pays for people living in remote areas.

Payments for Long-Term Care

Payments for long-term care under LTC 2.0 are on a fee-for-service basis and go directly to care providers. LTC 2.0 payments cannot go to foreign care workers, even though they remain a major source of care for the Taiwan population.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

NHI does not pay for complementary or alternative medicine. It does pay for TCM, including acupuncture, but only because it considers that a legitimate form of medicine. However, NHI only pays for Chinese medicines approved by Taiwan’s Food and Drug Administration.

Payments for Public Health and Preventive Medicine

NHI pays for a variety of preventive measures, although some of the funding for that coverage comes through separate agencies: the Health Promotion Administration and the Taiwan CDC. NHI also pays directly for the provision of some public health measures, like vaccines, through a series of public health centers that it operates across the island. Campaigns to improve awareness and behavior—on everything from tobacco usage to better eating habits—fall under the jurisdiction of the Health Promotion Administration.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

The Taiwanese have unfettered and radical choice. They are free to choose not only hospitals and physicians but also their own tests—without a physician’s order. Patients can go to any hospital, clinic, or health center at any time. Furthermore, they can literally walk up to the counter and ask for a test such as an MRI scan. On average the Taiwanese have 14 interactions with the health system per year, yet there is no problem of queuing.

Hospital Care

Taiwan has 484 accredited hospitals, including 7 dedicated to TCM. The vast majority of hospitals are private and nonprofit. The number of hospitals has declined significantly from a peak of 750 in 1995. Today there are 5.7 inpatient beds per 1,000 population.

All but one hospital, a TCM provider, contract with the NHIA. Overall, hospital spending accounts for 68% of total NHI spending. This high number reflects that the majority of hospital payments (about 55%) is for outpatient services by physicians at the hospital. This means about a third of total payments are for hospital in-patient care.

Taiwanese hospitals differ from hospitals in other developed countries in 2 main ways. First, facilities have a reputation for crowding, which likely reflects the high demand for services. Second, by comparison to other developed countries, Taiwanese hospitals are spartan. In many Taiwanese hospitals families and friends are expected to remain at bedside and, when practical, to attend to the patient’s daily needs like feeding and bathing.

Co-payments for some hospital and specialty care are higher without a referral, but the increased out-of-pocket costs remain modest by international standards—the equivalent of just a few US dollars, with exact figures depending on the circumstances.

Yet NHIA says that queuing is not an issue. Indeed, about 83% of hospital patients report getting care within 30 minutes.

Ambulatory (Outpatient) Care

In 2018, Taiwan had 22,089 outpatient clinics equivalent to physicians’ and dentists’ offices. Approximately one-third are dental offices.

Patients have totally free choice of physicians. They can see any doctor at any time, without a referral. The majority of physicians work in hospitals. When they provide outpatient care they do so through facilities that are part of the hospitals. In nonhospital clinics about 85% of physicians are in solo practices. For care after hours, the Taiwanese use hospital emergency rooms.

Providers and patients alike report that access to care is generally quick and accessible. This is possible only because the average physician has extended hours—until 9:00 p.m.—and sees 50 patients in a day, with the most popular ones seeing more than 100 patients. Both the medical community and NHIA officials worry that this feverish pace is leading to physician dissatisfaction and burnout. In 2017, an NHIA survey of physician satisfaction reported that 38.7% were unsatisfied and just 30.2% were satisfied.

The main appeal of private, concierge clinics is not to jump queues but to spend more time and get more attention from physicians or to see one of those handful of renowned physicians who have decided they can get enough income from private patients alone.

Although group practices are rare, some family physicians participate in a program called the Family Physician Integrated Care Project (FPICP). The FPICP, which dates back to 2003, creates networks of primary care providers (including pediatricians and gynecologists) who share patient records, provide 24-hour telephone consultations, and refer to common hospitals to coordinate care. Research suggests that patients in the program are more likely to get regular and preventive care.

Addressing urban-rural disparities is a major issue in Taiwan. One 2017 study, for example, found that three-fourths of rural communities had no dedicated pediatric clinics. To help address this, the Ministry now operates public health clinics that provide a wide variety of medical services, including both primary and preventive care. In addition, the government offers higher payment to providers who operate in underserved areas.

Mental Health Care

Taiwan has 43 major psychiatric hospitals and one teaching psychiatric hospital. After years of major shortages, the number of mental health beds increased. By 2014, there were 32 acute and 59 chronic hospital beds per 100,000 population. This is relatively high compared to other countries like China, which has approximately 32 psychiatric beds per 100,000 population, and the United States, which has under 12 beds per 100,000 population.

As in the rest of the world, Taiwan’s mental health community has pushed for deinstitutionalization. Initiatives like LTC 2.0 have helped by offering more community services for people with disabilities. NHIA officials say that the vast majority of people who get psychiatric treatment do so in outpatient settings—sometimes through primary care providers, sometimes through psychiatrists, sometimes through psychologists and other therapists, and sometimes through local health centers. But experts have said community support services remain highly underutilized, suggesting that people with mental health conditions are not getting all the support and treatment they need.

Long-Term Care

Taiwan has some nursing homes for the elderly and disabled, but the majority of people receiving long-term care do so in their own or family members’ homes. This heavy use of non-institutional care arises from 2 factors: (1) the government’s emphasis on aging in place and (2) the traditional Taiwanese beliefs that care for the disabled and elderly should be a family responsibility. To the extent that people need to hire caregivers, they can do so through agencies or the informal market. They continue to rely heavily on foreign-born workers, whose presence in the country the government has long supported, even though hiring those workers means forgoing the subsidies from LTC 2.0.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

According to the NHI, there are 800 clinics specializing in TCM—roughly 17% of all clinics.

Preventive Medicine

Patients can get preventive care in a variety of settings. The Ministry of Health and Welfare operates public health centers that provide basic screenings and immunizations. Even residents with regular physicians will frequently use the centers to get vaccines. They also provide services like testing for sexually transmitted diseases.

Electronic Health Records

One of Taiwan’s most famous delivery innovations is its electronic medical records system. Each patient has a card that includes personal information, such as address and insurance billing number. Providers use the cards to log interventions and file for reimbursement as well as to access online medical records through 2 systems: (1) MediCloud, which includes diagnoses, allergies, vaccinations, and records from the 6 most recent visits, and (2) PharmaCloud, which includes prescription information.

The Ministry uses the information from the cards to track utilization of services as well as to give public health authorities real-time information on potential disease outbreaks and epidemics.

My Health Bank is yet another electronic records system that gives patients cloud-based access to their medical histories. It is a work in progress in part because it has been difficult to get detailed, usable hospital records into the system. Interoperability is the big obstacle. Hospitals still keep clinical information, like scans or details of specific procedures, which are in incompatible information systems. Enabling those systems to communicate and allow wider access to the information is a focus of ongoing efforts by the Ministry.

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices (Taiwan)

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Taiwan uses both comparative effectiveness data and reference pricing to make decisions about drug coverage and pricing, pegging drug prices to the average of what other developed countries pay.

Pharmaceutical Market

Taiwan’s overall spending on drugs in 2018 was $6 billion USD (about 190 billion NTD) or $255 USD (8,000 NTD) per capita. By the standards of developed countries, the consumption of prescription drugs is relatively high, whereas prices are relatively low.

The government does not buy drugs directly. Clinics and hospitals purchase the bulk of them and then apply to the NHIA for reimbursement. Hospitals frequently negotiate discounts, enabling them to make a profit on the “spread”—that is, the difference between what they pay and what the NHIA reimburses. The NHIA is now taking steps to limit those profits by using data about past profits to determine future reimbursements.

Coverage Determination and Price Regulation

Taiwan’s Food and Drug Administration reviews drugs to make sure they are safe and effective. Once a drug is cleared, NHIA undertakes its own review process to decide whether it will go on the NHI formulary and, if so, how much the NHIA will reimburse for it.

First, the Center for Drug Evaluation (CDE), an independent agency within the Ministry, develops a report focusing on whether a drug should go on the NHI formulary. CDE assesses the drug’s clinical value generally by reviewing the findings of similar bodies in Australia, Canada, and the UK. If a drug is already for sale without coverage in Taiwan, the CDE will use data from electronic records to supplement the research from abroad.

The CDE prepares a report on the drug’s performance without recommendations. A panel of physicians, pharmacists, economists, and other outside experts then reviews this report and recommends both a price and a set of guidelines for reimbursement. Next, this panel’s recommendation goes to the Pharmaceutical Benefit Review (PBR) inside the NHIA. The PBR committee has both experts and stakeholders, including representatives from the drug manufacturers and patient advocates. If the PBR committee accepts the expert panel’s recommendation, the NHIA will begin listing and paying for the drug provisionally, subject to review by the Ministry director a year later. If the PBR committee disagrees with the expert panel, the drug company may reapply.

In making these decisions, both the expert panel and PBR committee must adhere to fixed pricing guidelines, based on their determination of the drug’s value. Specifically, they must classify drugs as breakthrough drugs (category 1), drugs that offer modest improvement over existing therapies (category 2a), or “me too” drugs that offer no meaningful improvement over what is available already (category 2b). For category 1 drugs the recommended price will be the median price of the drug in 10 developed countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the United States. For category 2a and 2b drugs the expert panel and the PBR committee may choose from several pricing options, including the lowest price in those 10 countries, the price in the manufacturing country, or the cost of comparable treatments already available in Taiwan.

This is not the end of the process, though.

The director general of the NHIA has discretion to negotiate even lower prices. If drug manufacturers are not happy with the offer, they can petition for reconsideration. The NHIA director general can grant that, going so far as to commission a whole new review. Eventually, if a manufacturer is not happy with what the NHIA is offering, it can simply refuse to sell the drug in Taiwan. This happens occasionally.

An official timeline allows 3 months for the CDE and expert panel review and then another 3 months for PBR committee deliberations. In reality the process can take longer, especially if the manufacturers end up appealing the decision.

Over the years, the NHI has gradually lowered prescription drug prices. According to some estimates, in 1995, when the NHI first launched, it was paying 89% of the 10-country index. After 2005, Taiwan’s reimbursement fell to around 50% of the index. NHIA officials take pride in their control of pharmaceutical costs, citing it as one reason they have run budget surpluses. Drug industry officials argue that the government manages drug pricing too aggressively, making it more difficult for people to get important treatments.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

Physicians can prescribe any drug approved for sale in Taiwan. Physicians can prescribe medications for off-label use, but they assume extra financial liability for adverse effects when they do. Using electronic records data, the NHIA monitors physicians’ prescribing patterns. When data show physicians overprescribing, the NHIA contacts the physicians with the data and encourages them to be more judicious.

Prices Paid by Patients

Out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs vary depending on the price of the medication. For drugs that cost less than $3.50 USD (100 NTD) there is no co-pay at all. From there co-pays rise steadily to a maximum of $7 USD (200 NTD) for any drugs that cost more than about $32 USD (1,000 NTD).

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

As of 2017, Taiwan had 1.97 Western-medicine doctors and 0.28 TCM doctors for every 1,000 population. The number of Western-medicine physicians has been rising steadily since the NHI’s inception.

Physicians work in 2 main types of settings. About 60% of physicians are hospital employees; the rest practice on their own in clinics or offices.

The Ministry does not keep official data on physician salaries, but annual average incomes are between $70,000 and $80,000 USD (2.1 and 2.4 million NTD), according to private-sector estimates. That is more than 4 times the median wage in Taiwan but is relatively low by international standards. Low wages and overwork have created concern over a “brain drain,” with some Taiwanese doctors working in mainland China—part or even full time—because the government there, desperate to handle its own shortage of providers, sometimes pays more.

Only 5% of physicians train as primary care or family physicians, although family medicine is part of the core training for all Taiwanese medical students. The rest train as specialists, though a significant portion end up working as general practitioners to meet the demand.

Physicians go through 6 years of education, including 2 years of premedical classes, and then at least 1 year of clinical rotations. Physicians who wish to provide TCM can train in a variety of ways—by studying TCM exclusively or by first studying Western medicine and then getting an extra degree in TCM. In either case, they must go through 2 years of dedicated training in TCM once their formal studies are over—and, as with Western-medicine physicians, pass certification tests (although the tests themselves are different).

Nurses

Taiwan has 159,621 nurses. That is roughly 6.8 per 1,000 residents, much less than typical European countries, such as the Netherlands with 10.5 per 1,000 residents. Nursing in Taiwan requires a 4-year college degree. Tuition is the same as it is for any other undergraduate study. Full-time nurses earn about $45,000 USD (1.4 million NTD) a year. Shortages are an ongoing problem.

CHALLENGES

Large majorities of the Taiwan population consistently say they are satisfied with the health system’s overall performance. It is not difficult to see why.

Virtually all citizens now have health insurance, enabling everybody to get the health care they need without experiencing financial hardship. They have free choice of hospitals and physicians and can even order their own tests. They get access to both Western and Chinese medicine. They do not generally have to wait for appointments or elective procedures. And they get all of this with very low out-of-pocket costs. Overall spending is low—lower than any European country per capita. Partly this is because of the system’s low administrative costs and partly because cost-control efforts, including the global budget, have been successful at restraining spending, including spending on prescription drugs.

Researchers in Taiwan have not studied the NHI’s effects on health outcomes as closely as researchers in the United States, but the available data offer good reason to think that the health of the Taiwanese has improved since the NHI’s implementation. It appears that with NHI more pregnant women are getting ultrasounds and Rh and other screenings. Similarly, there has been a decline in deaths from causes “amenable to health care.” Indeed, the most dramatic effects were among precisely those groups—the old and the young—who were most likely to gain health coverage from NHI.

The Taiwanese also developed a model for personal electronic medical records. These records do more than make the delivery of basic health care quicker and more convenient; they are also useful for both health policy and public health. The data facilitate careful tracking of utilization of services, allowing the NHIA to contact physicians whose billing patterns suggest excessive use of expensive tests or treatments. NHIA can also adjust reimbursements for Taiwan to remain within its global budget. In addition, during the SARS and H1N1 influenza outbreaks, Taiwan officials could track the disease in close to real time.

Yet Taiwan’s health care system has challenges. First, doctors see patients at a frenetic pace—50 to 100 per day—and work late into the night. This raises questions about quality and burnout. There is also the worry of a brain drain, with many physicians practicing overseas and many students being scared away from the profession. Although the number of Western-medicine physicians is increasing, it is still low. Given the high demand, low numbers of physicians, low salaries, and high workload, there is a threat at the very core of the physician-patient relationship. With burnout potentially increasing, the system could be at risk. Clearly more physicians need to be trained, the number of patients seen per physician lowered, and salaries increased. But this would produce higher costs and, because physician training takes years, cannot occur quickly.

Second, advocates for patients with cancer say the government does not approve new therapies quickly enough or pay what it takes to get the most advanced treatments. They worry this creates a 2-tier system in which only wealthy people can get those treatments. They say this may be the reason why cancer survival rates in Taiwan lag behind those in other medically advanced health systems. In a 2014 self-assessment, the Ministry of Health and Welfare gave the Taiwan system an “A” grade for its breast cancer mortality rate but a “D” for the cervical cancer mortality rate. It is unclear whether the challenges regarding cancer care are related to not having the latest drugs or to the amount of time physicians spend with patients and the quality of care they provide. Patients may blame access to drugs, but the real culprit may be the problem of physician shortages and overworked personnel.

In addition, with most physicians in solo practice and seeing so many patients per day, they lack infrastructure to coordinate chronic care and mental health care. Even with electronic medical records, it is difficult to make care plans and then administer them among different providers. Recent reforms have encouraged the Taiwanese to register with primary care physicians who can oversee care and give referrals. But so far it has not had much effect. This lack of chronic care coordination will be a growing problem as chronic diseases become more pervasive.

Long-term care is another big challenge, one that has bedeviled Taiwan for some time. The LTC 2.0 initiative has made more funding available to more people and made it easier for people who need assistance to stay at home rather than in institutions. But it remains available to a limited class of people who qualify based on condition and provides a limited amount of assistance, forcing a large number of Taiwanese who need long-term care to rely on their families or pay for it themselves. Of course, even with those deficiencies, the quality of long-term care in Taiwan appears to be high. One relevant data point is a 2015 worldwide survey by the Economist Intelligence Unit of Quality of Death in different parts of the world. Taiwan ranked 1st in Asia and 6th overall.

More spending could mitigate several of these challenges. Even a modest increase in national health spending would give the NHI plenty of money to increase physician salaries, train more physicians, and cover the newest drugs more quickly. And modest increases would still leave overall spending far below the average of OECD countries. Indeed, in 2008 Uwe Reinhardt proposed that Taiwan consider increasing its spending by 1% or 2% of GDP not only to acquire those new drugs but also to wipe out some of the out-of-pocket costs that NHI enrollees still have to pay. It has not happened.

Increasing health spending would require the Taiwanese government to raise more money—either by pushing up the income-related premiums, increasing the nonwage or lottery and tobacco taxes, or finding some other new revenue source. Even in Taiwan, with its relatively low health care spending, raising taxes for health is politically challenging. In the meantime, leaders of groups representing cancer patients and other people battling serious illnesses have proposed an alternative, stopgap solution: some kind of balance-billing scheme—like the one in place for those handful of medical devices—for cutting-edge cancer drugs that the NHI is not yet ready to cover. But policymakers have not given the idea serious attention.