CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHINA

After multiple efforts to expand insurance coverage, China today is close to realizing a major achievement: providing health insurance to almost its entire population. Unfortunately this insurance is broad but not deep. Most payment for medical services—and especially for long-term care—is still out of pocket.

What’s more, the delivery system has not matched the progress in insurance coverage. Chinese patients go to hospitals for almost all conditions, from simple respiratory infections and routine diabetic checks to serious cancers. There is little ambulatory primary care available, partially because of the way physicians are licensed, partially because of extremely low pay and prestige, and partially due to patient habits.

Although hospitals are considered the best place to receive care, there is deep distrust of doctors and hospital administrators because of endemic corruption. Physicians accept “red envelopes” stuffed with cash from patients as well as kickbacks from drug companies for prescribing their medications. Consequently, one physician noted that “patients do not have much trust in health professionals. When they come to see a doctor, most of the time their position can best be described as half trust and half doubt.” In the extreme, this distrust results in violent attacks on physicians, nurses, and other medical personnel.

These issues are not new to Chinese officials. They have plagued the system for decades. And health policy experts acknowledge that fundamental change is needed to improve the system. And yet, despite big changes in insurance coverage, funding, and public health services, implementing innovations in how care is delivered and how physicians and patients behave has proven almost impossible.

HISTORY

China’s current health care system originated in 1982, when the government overhauled the centralized, Communist health care system that had been established more than 30 years earlier when Mao Zedong and the Communist Party came to power in 1949.

Under the centralized system the national government set the budget for each sector of the health care system, fixed the income for doctors, nurses, and administrators, and implemented 2 different health insurance systems—one for urban areas and another for rural areas. There was no private insurance. In urban areas the Government Insurance Scheme (GIS) insured officials, staff, and their dependents at government agencies, schools, universities, and research institutes. The Labor Insurance Scheme (LIS) covered employees and their dependents at state-owned factories. Poverty aid programs insured unemployed urban residents. In rural areas the Cooperative Medical Scheme (CMS), a prepaid health security program, covered most of the population, but with few services. CMS ran the village and township health centers, in which so-called barefoot doctors, community-based doctors with little health training, provided both Western and traditional Chinese medical care at basic levels.

In the 30 years after 1949 life expectancy increased from 35 to 68 years, infant mortality fell from 200 to 34 per 1,000 live births, and vaccination levels increased, reducing the spread of infectious diseases.

Despite these achievements, the political and economic shifts of the early 1980s initiated the disintegration of most of the health care system. In the 1980s, China began a dramatic shift toward a market-based, privatized economy. For health care this meant that the formerly collectivist structure became more privatized, individually financed, and shifted its orientation from prevention to acute care. In 1978, the central government began to transfer financial responsibility for health care to the regional and local governments. The 1982 constitution made this shift official. Budgetary decisions were delegated to local governing bodies, and much more of the funding came from payments from individuals instead of the national government. These changes reinforced the preexisting disparities between care in the coastal, urban provinces and the inland, rural provinces. In addition, power over national health care transferred from the Communist Party (CCP) to the Ministry of Health (MOH). Because fiscal decision making had been decentralized to local and provincial governments, the MOH could not implement nationwide policy changes.

Prior to the early 1980s, the government had tight controls over how much hospitals and clinics could charge for most services. But as part of the 1980s reforms, the government also imposed a new price-regulation system that increased costs and decreased access. It allowed facilities to earn profits on drugs and tests. Physicians also began to receive bonuses for bringing in more revenue in a fee-for-service model. Around the same time, the rural health insurance scheme collapsed as a result of rising premiums and subsequent disenrollment, causing hundreds of millions of rural citizens to lose their coverage. Most of the previously government-sponsored clinics transformed into expensive, fee-for-service health centers. To even make a living, the barefoot doctors, now unemployed, turned to private health care provision—charging high fees, selling drugs, and abandoning their previous emphasis on preventive care.

Health care costs increased dramatically. Between 1980 and 2000 national health expenditures rose by 4,000%. In response, the government reintroduced some price controls, but this gave patients an economic incentive to stay in hospitals longer than medically necessary, thus wasting resources and exacerbating shortages of medical services.

Faced with high operating costs and little government support, hospitals started charging high markups for specialty services, tests, and drugs not covered by price regulations. By 1992, these markups accounted for about three-quarters of hospital funding. Demand for hospital services grew as rural residents with the means to travel began to come to cities seeking care. Focus on public health diminished because physicians had few incentives to emphasize preventive measures. Population health progress slowed, and some infectious diseases began to reemerge.

Since 2000, China has taken major steps to overhaul its health care system. After an outbreak of SARS in 2003, the government reinvigorated its preventive health measures, initiating thousands of local-level projects to prevent and control disease. In 2002, President Hu Jintao’s government began to look at ways to decrease costs and increase access.

Insurance reforms had already begun in 1998 with the creation of the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), which combined and replaced the old GIS and LIS systems. UEBMI put all workers at urban, state-owned enterprises into a citywide risk pool, which stabilized the enterprises’ finances. All employers—private and state owned—were required to offer employee coverage with medical savings accounts (MSAs) and catastrophic coverage, funded by payroll taxes. However, the UEBMI pools were largely populated by aging and retiring workers. Consequently, costs began to grow. Although enrollment was mandatory, UEBMI often did not cover younger people because they were migrant workers and not considered urban residents eligible for the insurance. In 2007, the government introduced a 2nd urban insurance scheme called Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), targeted at unemployed or informally employed urban residents. This plan included students, children, the elderly, poor, and disabled. The central government heavily subsidized it.

Beginning in 2003, rural health care received a similar overhaul. China established the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS), a re-creation of the old CMS overseen by the MOH. Unlike its predecessor, NCMS was voluntary and focused on acute care. It pooled risk at the county level and was geared toward covering hospital and emergency expenditures. Government subsidies were initially low, which required high out-of-pocket payments. Nevertheless, by 2007, 86% of China’s counties enrolled in NCMS, covering 730 million rural residents.

In 2009, following 4 years of internal debate over how to resolve the issues of declining coverage rates, limited rural access to care, increased incidence of public health crises, and rapidly rising out-of-pocket costs, China introduced a comprehensive reform plan. This reform had 5 objectives:

1. Expand insurance coverage.

2. Increase funding of public health.

3. Expand local-level health care infrastructure.

4. Form an Essential Drugs List (EDL).

5. Improve public hospital operations.

This required an enormous investment by the central government, which by 2015 had reached $354 billion USD annually. Unfortunately, the plan fell short of its goals.

Although at the end of 2011, 95% of the population was covered, this was more in name than in reality. About 200 million rural-to-urban migrant workers, who may have been covered by NCMS in their hometowns, lacked coverage in the cities where they actually lived and worked. In addition, most inpatient and outpatient coverage still required high out-of-pocket payments, often totaling more than 50% of the bill. Public health funding increased from $2 to $3.50 USD (15 RMB to 25 RMB) per capita, but it is unclear if this has had a tangible effect on population health.

The central government worked with local governments to create township health centers (THCs) that housed primary care physicians who focused on both acute and preventive care, but rural residents still preferred to use village clinics and county hospitals. The Essential Drugs List (EDL), a list of 520 medications covered by public insurance and required to be sold at cost, was created, and some prices dropped. But many hospitals either did not comply with the law or even induced demand for inpatient services to offset revenue lost through lower drug prices. Even worse: the reforms to the public hospital system, which were supposed to improve the efficiency of care, were slow to materialize.

More recently, reforms have been incremental. In 2015, the government announced that it was removing price controls on most drugs, with new regulations that would rely partly on market pricing. Similarly, in 2015 the government encouraged more private-sector involvement in the health care system, allowing patients with public insurance to receive reimbursement for privately provided services. The government has also begun to investigate—and prosecute—corruption in the health care sector. And it pledged to increase health care spending to 7% of GDP by 2020 in an effort to combat chronic illnesses.

The disparities between URBMI and the NCMS were apparent from the beginning. In the rural areas the NCMS risk pools were province based. Consequently, they were smaller, riskier, and cost more than urban risk pools. In addition, because rural health care was much harder to access—and therefore more expensive than care in urban areas—NCMS enrollees were paying more out of pocket for fewer and lower-quality health care services. Finally, premium contributions in the rural insurance scheme were significantly higher as a percentage of income than in the urban one.

Significant portions of the population who technically had health insurance coverage were in reality unable to receive services. Chinese residents had to register with their local municipality and could only receive benefits from social insurance programs in the locality where they were registered. Thus, migrant workers who leave rural areas for work in the cities are denied social insurance program benefits, including health coverage, because they live outside their registered municipality. Furthermore, each locality is assigned either urban or rural status. Residents in rural localities could only enroll in NCMS, while those assigned urban status could only enroll in URBMI. But as the urban-rural distinction was being phased out throughout the early 2000s and 2010s, provinces began to merge their NCMS and URBMI programs. To mitigate the problems of paying for migrants’ health care, in 2017 the Chinese launched a cross-province medical settlement program that benefited a few million workers.

In December 2016, the national government announced that it would formally integrate NCMS and URBMI into one program: the Urban and Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI). Each province was required to submit a plan to merge the 2 systems at the provincial level by the end of 2019. In 2018, a new government agency, the National Health Commission (NHC), was formed to oversee all state health coverage.

By 2016, many urban provinces had in reality almost no NCMS enrollees, and so this enormous shift in governance was less arduous than it might have seemed. Still, this period of transition will test whether China can truly create a unified system of universal coverage.

As with many aspects of government, the Chinese health care system is centralized in theory but fragmented in fact. This produces significant disparities between cities, provinces, and programs based on wealth and location, and it makes coordination difficult. As these issues emerge, the government must continually grapple with the challenges of insuring the world’s largest population through a decentralized and underfunded system.

COVERAGE

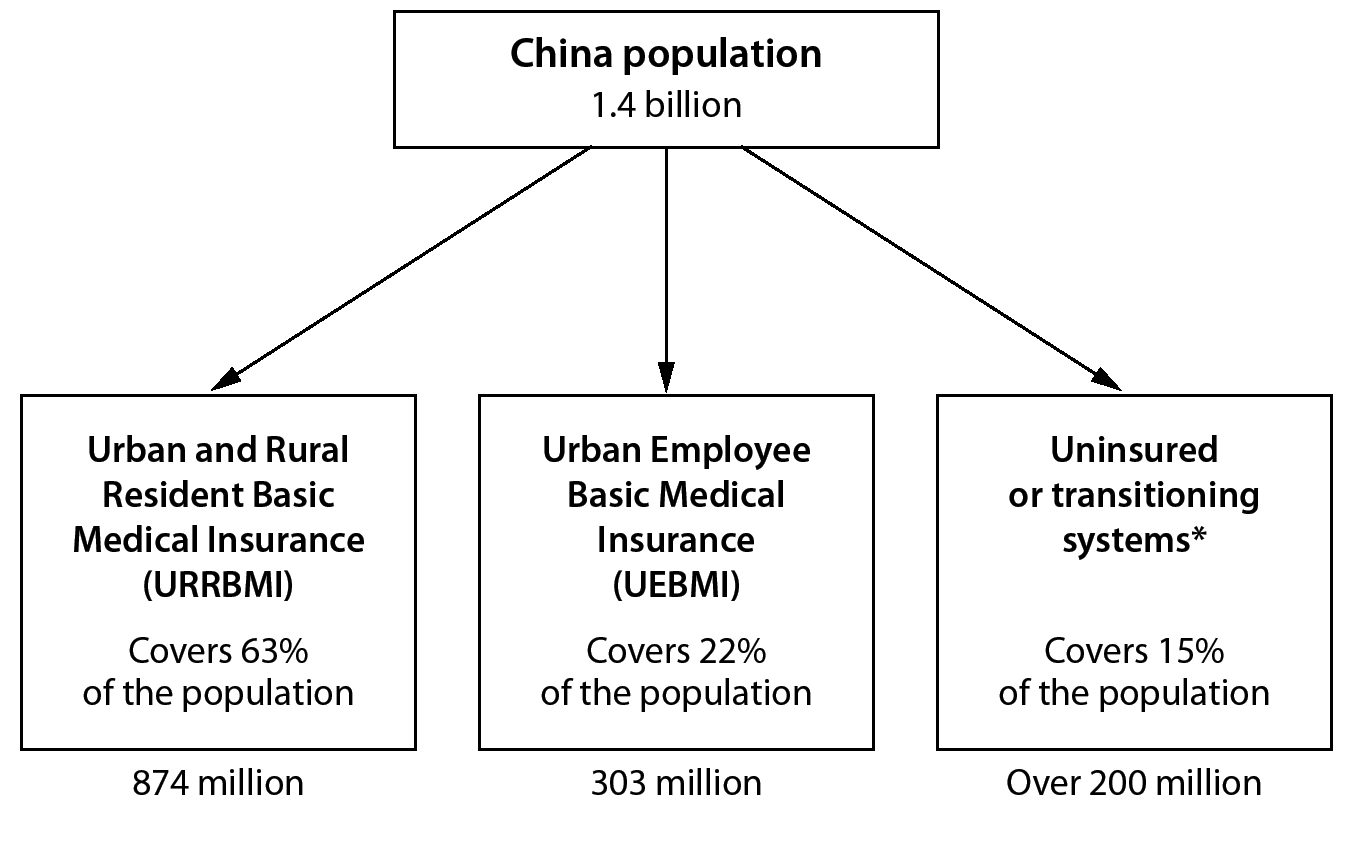

China is a country of 1.4 billion people, 60% urban and 40% rural, spread across 22 provinces, 4 municipalities, and 5 autonomous regions (which, for the purposes of health insurance, are considered part of China).

There is no universal legal mandate for health insurance coverage. URRBMI—the new health insurance system introduced in 2016 to cover both urban and rural residents—is voluntary. Nevertheless, China is nearing universal health coverage. Approximately 95% of the population is covered by one of the publicly funded programs.

Public Health Insurance

All publicly funded coverage is person specific. This means that health insurance programs cover individuals, not their family or dependents, and therefore each person must enroll separately.

Two publicly funded health insurance programs cover 85% of China’s population. First, the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) provides health insurance to all urban employees of government agencies, state-owned enterprises, and private enterprises. Participation in UEBMI is mandatory for employees and employers. In 2017, UEBMI covered 303.2 million people, but it does not include coverage for employees’ family members and dependents.

Second, the Urban and Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI) provides health insurance to other urban residents, including children, the self-employed, students, and elderly adults, as well as to all rural residents regardless of whether they work. Enrollment is also voluntary, and the government pays most of the cost for covered services with low individual premiums. By 2017, URRBMI covered 873.6 million people. URRBMI was supposed to be fully implemented at the end of 2019. It should now cover the entire population formerly covered by the URBMI and the NCMS—or more than a billion people. It remains to be seen whether URRBMI will succeed in providing coverage for all those people and expanding coverage to those who previously struggled to obtain it.

Figure 1. Health Care Coverage (China)

*Government reports 5% uninsurance; remainder still transitioning from the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS) to URRBMI.

Foreign citizens residing in China are also entitled to coverage under whichever program is applicable to their employment status.

There is no nationally standard basic benefits package. Covered services vary widely between provinces because local health officials can determine some aspects of coverage. In theory both UEBMI and URRBMI cover primary care, specialist care, emergency room visits, hospitalization, and mental health care along with prescription drug expenses. Traditional Chinese Medicine, some dental and optometry services, and sometimes home and hospice care are covered depending upon the province. In most areas, though, only acute inpatient and outpatient care are actually covered, although UEBMI enrollees can use their medical savings accounts to cover other health expenses, such as drugs or dental care. Neither plan covers long-term care.

Preventive health care is covered separately through a public health program funded by the central government and administered by local government health clinics. Every Chinese citizen is entitled to free preventive care, including immunizations and disease screenings. Public health clinics also track and manage infectious diseases in local communities.

Private Health Insurance

Only about 5% of Chinese residents have any form of private insurance. Private health insurance is often sold in combination with life insurance. Most of these policies are critical-illness policies, which apply only to prespecified illnesses—such as cancer—and pay out a lump sum if the policyholder is diagnosed with one of those conditions. Private health insurance is largely supplementary to public insurance and is often offered by large multinational employers, although some higher-income individuals only use private insurance. Private insurance can offer access to better-quality care because some private hospitals, which tend to be less crowded and of higher quality than public ones, do not accept public insurance.

Despite encouragement from the government to expand its reach after the 2009 health reforms, the private health insurance market has remained small. In 2015, the market was about $36.7 billion USD (250 billion RMB) and has grown at about 36% each year since 2010. This market will likely continue to grow as more middle- and upper-middle-class citizens look for a way to cover the superior care they hope to receive at private hospitals.

FINANCING

China spends about $1.33 trillion USD (9.2 trillion RMB)—6.2% of its GDP—on health care annually. This translates to roughly $960 USD per capita. Of this, about 62% is funded by public sources. The rest comes from private spending, including supplemental insurance plans, private care, and, mainly, out-of-pocket payments for various drugs and services that public insurance does not fully cover. Health care expenditures have risen almost 12% annually since 2010.

Public/Statutory Health Insurance

UEBMI, the employment-based public insurance scheme for urban workers, is funded by a payroll tax. Employees pay 2% of their salary and employers contribute 6% to 8% of the employee’s salary. This money is divided into 2 pools. Each individual has a medical savings account (MSA), made up of their contribution plus 30% of the employer’s contribution. The other 70% of the employer’s contribution goes into a social pooling account (SPA). Retirees are exempted from the employee contribution but are still covered by UEBMI.