Administered by the individual, the MSA is mainly used for out-of-pocket payments for outpatient services and drug purchases. Local governments administer the social pooling account. The SPAs cover in- and outpatient services for acute and catastrophic illnesses or accidents. Before the SPA coverage goes into effect, individuals must pay a deductible, set at about 10% of the average annual wage of a local worker. Individuals are also responsible for a coinsurance of 5% to 20% of the health bill. The SPA will pay health care costs up to 6 times the local employees’ average annual wage. At this point, if the MSA is also exhausted, all expenses must be paid out of pocket. Unspent money in MSAs is rolled over to the next year.

The details of each province’s exact URRBMI financing structure will be different because they are at different stages of merging the old URBMI and NCMS to create URRBMI. As an example: in Beijing URRBMI is funded by individual premium contributions and government subsidies. Annual premiums for the elderly, children, students, and those of working age are $26 USD (180 RMB). For people with disabilities, those beneath the poverty line, and orphans, there are no premiums, but there may be high individual deductibles. The national government contributes the vast majority of the URRBMI budget out of general tax funds. In 2015, 78.2% of the old URBMI budget came from the central government; URRBMI might be financed in the same way.

Unlike UEBMI, there are no medical savings accounts (MSAs) in URRBMI. The individual and government contributions go only into an SPA. Like the SPA for UEBMI, the URRBMI SPA covers inpatient and critical outpatient services—but much less generously. For inpatient treatment, the deductible ranges from $43 to $188 USD (300 to 1300 RMB) for the first hospitalization (depending on the type of hospital) and half the original deductible for subsequent admissions, with 20% coinsurance. The maximum the SPA will pay for inpatient coverage is $28,969 USD (200,000 RMB). After that, individuals must pay all health expenses out of pocket. For critical outpatient treatment there is a $14 USD (100 RMB) deductible and 45% coinsurance. Each person also gets a $207 USD (1430 RMB) subsidy from the government for out-of-pocket expenses.

Private Health Insurance

Individuals purchase private health insurance policies out of pocket. There is no government subsidization of private health insurance. Some large multinational corporations purchase group reimbursement policies for their employees. These policies cover care at private hospitals, but they are fairly rare.

Long-Term Care

The one-child policy has created a rapidly aging population without sufficient familial and social support for the elderly. Recognizing this, in June 2016, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MoHRSS) launched an experimental long-term care insurance program. The goal was to create a national long-term care system by 2020. Long-term care insurance is currently only available in the 15 pilot cities designated by the MoHRSS. The MoHRSS provided fairly little guidance to the pilot cities on how to structure their systems, suggesting only that the policy should:

• cover those with long-term disabilities,

• be limited to UEBMI enrollees,

• be funded by alterations to the structure of UEBMI funding,

• pay 70% of the costs that meet reimbursement requirements, and

• gradually expand both the covered population and the benefit package over the course of the pilot.

Few details on individual cities’ financing structures are currently available.

Public Health

All Chinese citizens can receive basic public health services, including immunizations and other preventive care, at no upfront cost through a national public health service program. In 2016, this program had a per capita budget of $6.50 USD (45 RMB), funded by the central government. It is under the purview of the National Health Commission (NHC).

PAYMENT

Payments to Hospitals

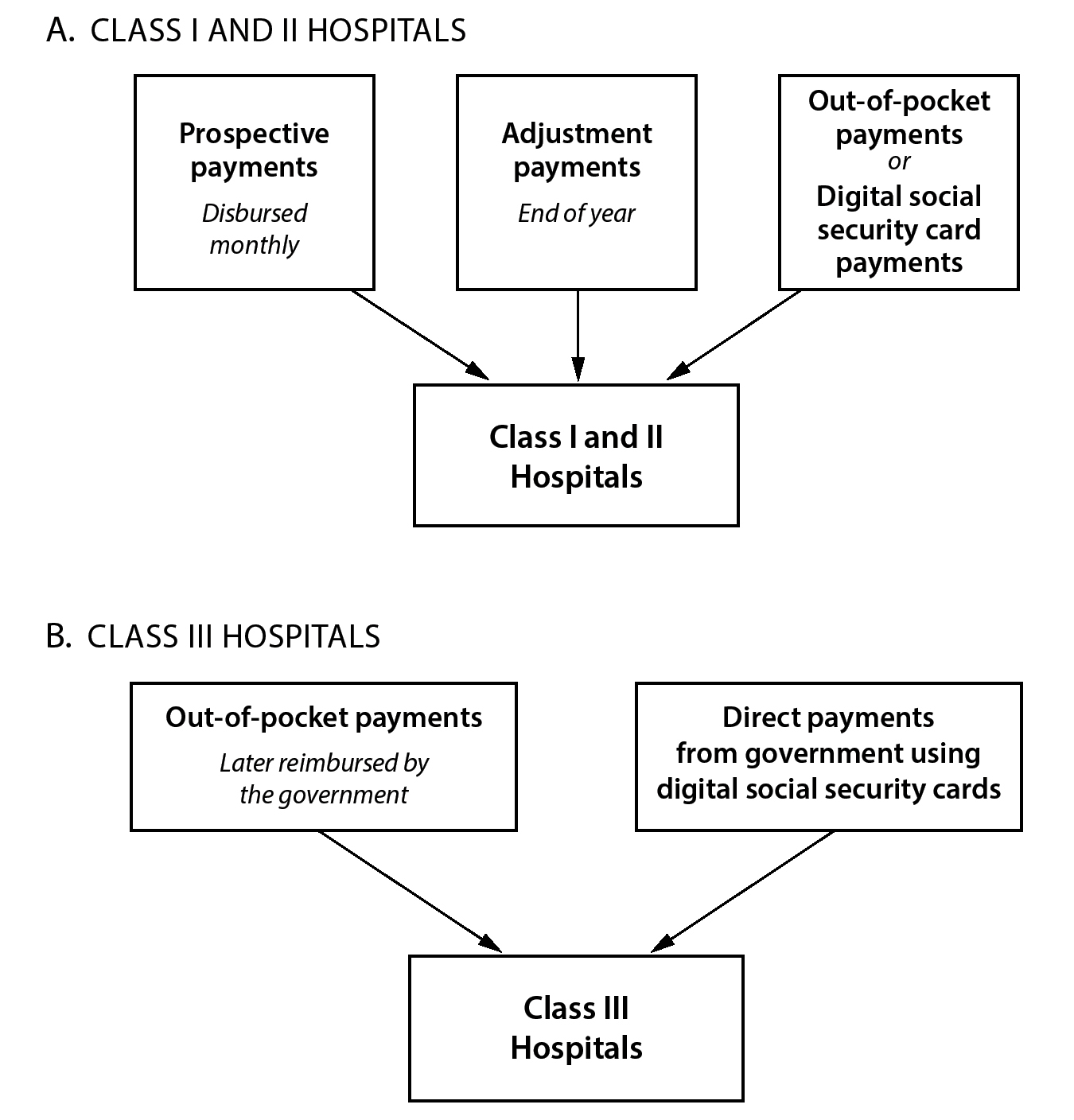

There are 2 different payment schemes for hospitals.

Small- and medium-sized local (known as Class I and Class II, respectively) hospitals receive annual prospective payments from the National Health Commission (NHC). At the beginning of each year, the NHC will estimate what the hospital’s costs will be. Monthly it disburses payments. At the end of the year, there is an adjustment payment if costs were above or below the prospective payment. Hospitals can receive bonuses if their costs were under 80% of the estimation. If costs were above 120% of the estimation, hospitals must share 50% of the excess expense. Patients at local hospitals must only pay the out-of-pocket portion of their bill; the prospective government payment covers the insured portion.

Large cross-district and national hospitals (Class III) are the most prestigious and have the most highly regarded doctors on staff. These hospitals are mostly funded by patients’ out-of-pocket payments. Patients at Class III hospitals must pay the full bill at the point of service and then send receipts to the local government to be reimbursed for the insured portion of the bill. However, this practice is beginning to change. In 2018, patients could use their digital social security cards to settle their medical bills at the point of service at most public hospitals.

Private hospitals can receive payments from the government in the same way that Class III hospitals do as long as they have been designated, or appointed, by the government. Local governments can designate hospitals, functionally making them in network for government health insurance payments.

Payments to Ambulatory Care Institutions

Township and community health centers, which provide most of China’s primary care, have 3 sources of revenue: fee-for-service (paid by health insurance or patients), drugs (from dispensing medications), and government subsidies. The government subsidizes the gap between clinics’ revenue and expenditures. On average, subsidies are about half of total revenue for primary care institutions.

Figure 3. Payment to Hospitals (China)

Payments to Physicians

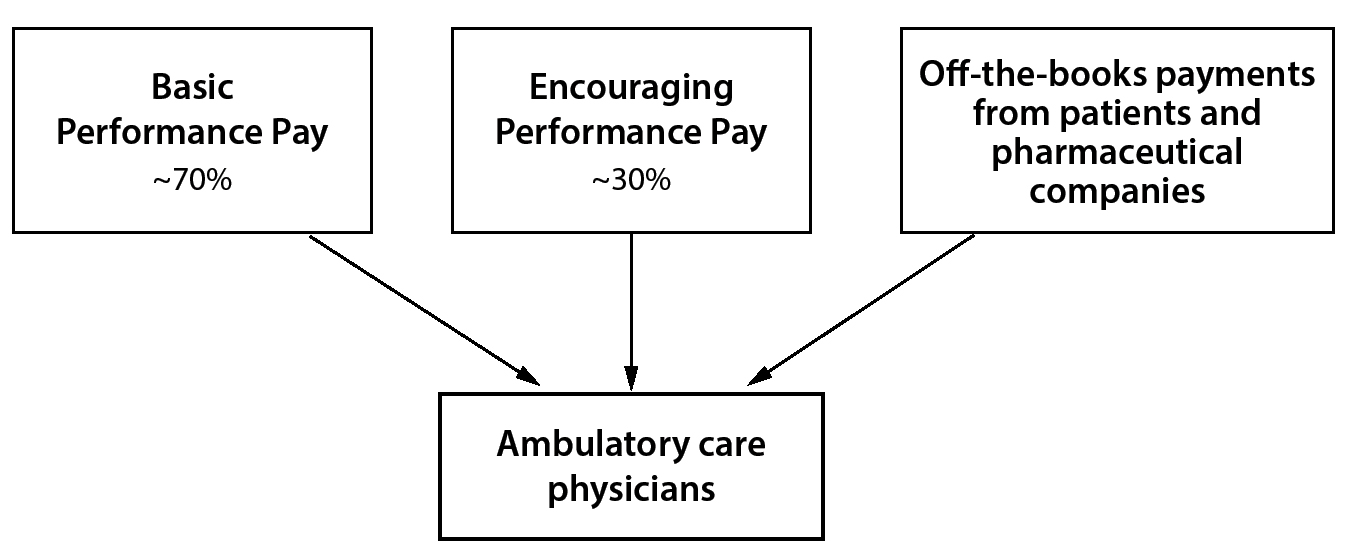

Doctors in outpatient primary care institutions are paid a salary, which is determined by 2 factors: Basic Performance Pay and Encouraging Performance Pay. Basic Performance Pay is a fixed amount that varies from doctor to doctor depending on job title, experience, location, and place of practice. It usually makes up about 70% of a physician’s wage. The other 30% is Encouraging Performance Pay, which is theoretically intended to encourage better-quality care. However, it is usually paid out based on the volume of services a physician provides.

Figure 4. Payment to Ambulatory Care Physicians (China)

Village doctors, providing primary care in rural village clinics, are paid almost entirely on a fee-for-service basis. They receive low per capita government subsidies for providing the basic public health services that UEBMI and URRBMI cover.

Payments for Long-Term Care

Other than in the pilot cities designated by the MoHRSS in 2016, long-term health care is paid for by patients and their families entirely out of pocket.

Payments for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is covered by the public health insurance system. Payments for such services are made the same way as payments for Western health care services, whether they are administered in primary care institutions or in hospitals.

Payments for Public Health/Preventive Medicine

There is no upfront payment for basic public health services. The central government distributes low per capita subsidies to clinics and other primary care institutions for providing these services.

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES

For many reasons, health care delivery in China is extremely hospital centric. The vast majority of physicians are specialists practicing in hospitals. This is in large part because care in physician offices is viewed by both physicians and patients as much lower quality and much less prestigious. Consequently, prominent physicians do not offer nonhospital outpatient care, and new physicians are hesitant to practice in nonhospital settings. Thus, there are few freestanding outpatient physician offices. There is no gatekeeper model. Patients do not need a primary care physician or GP referral to see a specialist.

Reinforcing these cultural practices that emphasize hospital-centric care is the payment system. Because the 2 social insurance schemes do not cover much beyond inpatient and critical outpatient care, patients go to hospitals as the main point of contact for health care services.

Hospital Care

As of 2017, there are 30,000 hospitals in China, with 6.1 million hospital beds. Of these hospitals, 12,000 are public and 18,000 are private.

Hospitals in China are divided into 3 groups, Class I (primary), Class II (secondary), and Class III (tertiary) hospitals. Primary hospitals are typically small, with 100 or fewer beds, providing little specialized care. Secondary hospitals are larger (100 to 500 beds) and usually serve a broader region. They provide comprehensive medical care and also perform medical research and education at the regional level. Tertiary hospitals are national and cross-regional, and they perform both specialized care and specialized research. They usually have more than 500 beds and are the most prestigious.

Hospital care is in high demand, as citizens believe—often correctly—that hospitals are the best place to receive quality care. Rural residents will often travel long distances to urban hospitals. As a result, hospitals tend to have long waits.

Ambulatory (Outpatient) Care

Doctors, village doctors, and nurses provide ambulatory care in health centers and clinics throughout the country. As of 2017, there were 37,000 township health centers, 35,000 community health service centers, 230,000 clinics, and 638,000 village clinics delivering such services.

In most urban areas physicians see their patients at hospital facilities. Except for a small but growing number of private physician offices, the vast majority of ambulatory care is provided in hospital facilities.

Mental Health Care

Mental health care is largely cordoned off from other medical care, although the government is attempting to integrate it more fully into primary care. There are around 30,000 psychiatrists, 60,000 psychiatric nurses, and 450,000 psychiatric beds for a population of 1.4 billion—about the same number of practitioners as the United States for a population 4 times the size. Like most health care in China, mental health care is hospital based.

Around 45% of all mental health resources—institutions and personnel—are located in 11 eastern provinces, indicating an even more unbalanced distribution of resources than is typical in the Chinese health care system. Areas composed mostly of ethnic minorities, such as the Tibet Autonomous Region, have few to no psychiatrists.

Long-Term Care

There is no public structure for long-term care delivery, although the number of nursing homes is rising rapidly and private in-home nursing services are becoming more widely available in cities. In 2017, there were approximately 145,000 nursing homes. Most long-term care is informal and administered by family members. But with a one-child policy, there is only one female caregiver—the married daughter or daughter-in-law in a couple—for 4 parents.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

There are about 4,000 Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) hospitals and 42,528 TCM clinics, with roughly 450,000 TCM practitioners. TCM facilities across the country receive about 910 million annual visits. All TCM practitioners are required to pass exams administered by provincial-level TCM organizations and obtain recommendations from at least 2 previously certified TCM practitioners. Allopathetic physicians may also specialize in TCM.

Preventive Medicine

Local health institutions deliver preventive care services, including disease screening and immunizations.

PHARMACEUTICAL COVERAGE AND PRICE CONTROLS

Pharmaceutical Market

China’s pharmaceutical market is the 2nd largest in the world after the United States. It reached $108 billion USD in 2016 after 5 years of annual growth rates exceeding 25%. Pharmaceutical expenditure comprises 1% of total GDP and 17% of total health care spending. There are 5,000 to 7,000 individual local pharmaceutical manufacturers, with most producing a small slate of generic products. Of total drug sales, just under two-thirds are generic drugs, making the Chinese generic market the largest in the world.

Coverage Determination

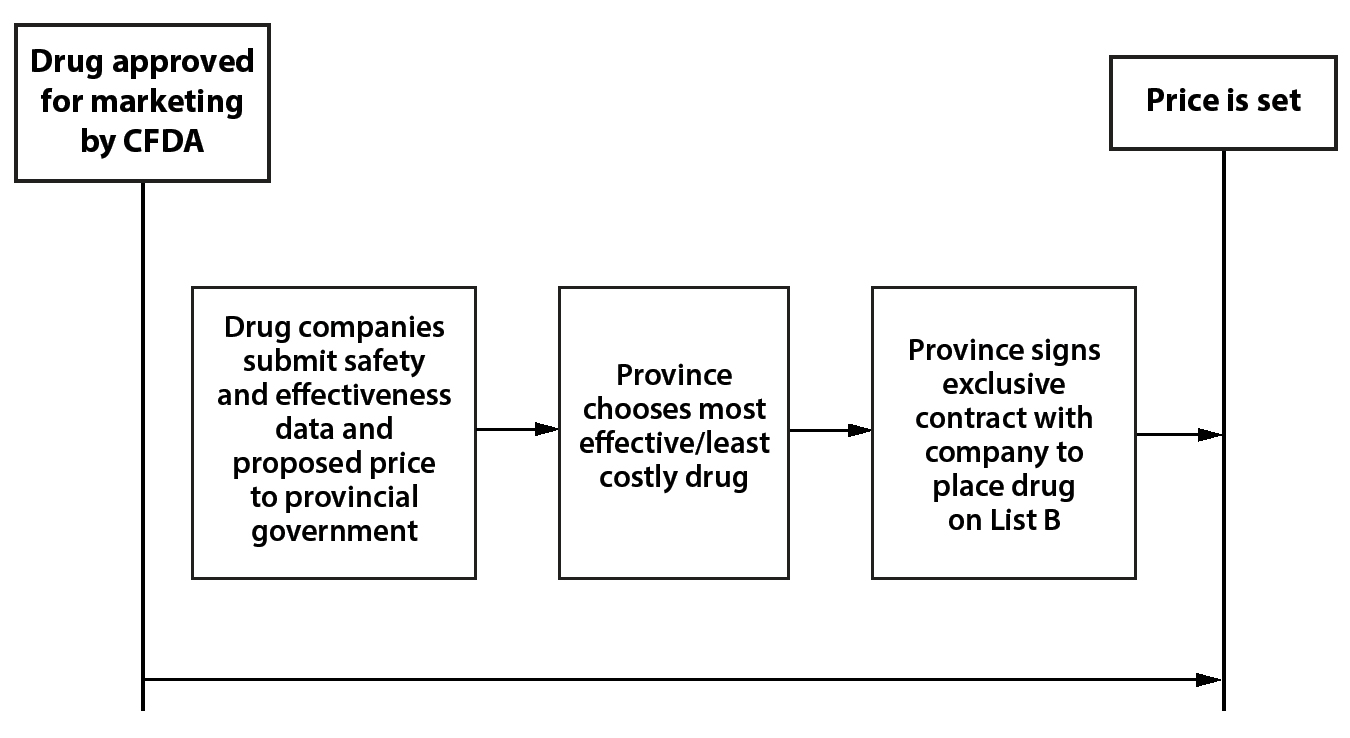

After the Chinese Food and Drug Administration grants prescription drugs market authorization, the drugs can be placed on 2 reimbursement lists. The Essential Drugs List (EDL), created in 2009, catalogs medicines that the Chinese government considers essential and that every public primary care clinic must be fully stocked with by 2020. There are around 700 drugs on the EDL, and about one-third are TCMs. Currently the process for selecting EDL drugs is undergoing reform.

The National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) was created in 2000. As of 2017, it covers about 1,300 Western drugs and 1,250 TCMs. The National Health Commission (NHC) selects drugs for its formulary in 2 lists, or tracks. List A drugs are completely covered by state health insurance and are given priority use at public hospitals and clinics. Regardless of province, the UEBMI and URRBMI insurance schemes cover these drugs. Most List A drugs are widely used, generic drugs that are relatively inexpensive and considered essential. There is substantial overlap between the drugs on List A and the EDL, as the NRDL predates the EDL by almost a decade.

Figure 5. Regulation of Pharmaceutical Prices: Competitive Bidding (China)

In contrast, List B drugs are not completely covered. Provincial governments may remove up to 15% of the drugs from the national List B, add an equivalent number of different drugs to their provincial List B, and designate those drugs as covered. List B drugs also may require co-pays, which are determined by the provincial governments and can be substantial. Drugs on List B tend to be newer, and many do not yet have generic substitutes.

Drugs that are not included on the EDL or the NRDL must be paid for out of pocket. Drugs are added to the formulary about every 5 years as part of the same process by which their price is determined.

Price Regulation

China currently has 2 different drug pricing systems. It is gradually moving from a negotiating process toward a competitive bidding one.

Under the negotiation system currently being phased out, there are 3 phases of price determination. Negotiations under this system last took place in 2017. In the first phase, expert committees made up of doctors, academics, and government experts selected drugs to participate in price negotiations. In the 2017 round of negotiations, about 4,000 experts participated in the selection process, and 44 drugs were chosen for negotiation.

In the 2nd phase, the government established 2 independent groups of experts to determine a target price at which to begin negotiations. One group evaluates the pharmacoeconomic value of the drug in question, and the other looks at the government’s capacity to reimburse the drug. This process is confidential, and manufacturers are not told the target price even once it is reached.

Finally, in the 3rd phase, the manufacturers are given a chance to negotiate the price. If manufacturers offer a price more than 15% higher than the target price, negotiations cannot begin, and the drug will not be admitted to the formulary; if they offer a price less than 15% greater, negotiations can begin. However, the negotiated price cannot exceed the government’s target price. This process, although strange, gives manufacturers an incentive to open negotiations with a lower price, thus giving the government a good chance at getting a low price. In the last round of negotiations in 2017, 36 of the 44 drugs were admitted to List B of the formulary, and none had more than a 20% co-pay. On average, the final prices were 44% lower than prices under the previous drug negotiation scheme.

Recently China introduced a competitive bidding process for pharmaceuticals that is being piloted in 4 large cities and 7 provinces. In this process drug companies submit safety and effectiveness data to the provincial or city government along with a proposed price. The provincial government then chooses the drug that is effective and the least costly; it then signs a contract with the producer to place that drug on their province’s List B. The company then must sell that drug at the agreed price, completely crowding out competition in the province. The first round of this bidding ended in December 2018, and prices fell an average of 52% from previous negotiated prices.

This pilot process will likely be scaled up to the national level in the next 5 years.

Regulation of Physician Prescriptions

There is little regulation of physician prescriptions. This, in combination with relatively low physician salaries, has led to endemic corruption among doctors. Physicians often take large payouts from pharmaceutical companies in exchange for prescribing their drugs. Although illegal, this practice is pervasive because it allows physicians to substantially increase their income.

Prices Paid by Patients

In theory, patients are well insulated from high drug prices. But, as in many parts of the Chinese health care system, reality is bleaker. Few drugs are fully covered, and those that are covered often come with high co-pays. In addition, many drugs are not included on either List A or List B, so they must be paid for totally out of pocket.

The government claims that individuals pay no more than 30% of their health care spending out of pocket. However, according to one prominent health care researcher, “Many other data indicate that individuals pay more than 30% because there are many drugs not on the formulary, so individuals pay a lot out of pocket.”

HUMAN RESOURCES

Physicians

There are 3 kinds of doctors in China: licensed doctors, who must complete medical school; licensed assistant doctors, who need only complete 3 years of junior medical college; and village doctors, who can work in village clinics with only a technical school degree. In 2017, there were 3.4 million licensed doctors and licensed assistant doctors, or about 2.4 doctors per 1,000 people, up from 1.7 per 1,000 people in 2000.

As in most countries, Chinese students who want to become licensed doctors begin training immediately after graduating from high school. Training takes 5 years for a medical bachelor’s degree or 3 years in a junior medical college. Students may then choose to continue for 2 or 3 more years to gain a master’s or doctorate in medicine, which usually focuses on either experimental medicine or clinical diagnosis. About half of medical students continue on to graduate education. Importantly, an advanced degree is not required to become a practicing physician in hospitals or clinics. The Ministry of Education requires all 5-year programs to provide training in TCM as part of the mandatory curriculum. Doctors may choose to specialize in TCM at the medical bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral level.

There are about 180 medical universities, graduating about 600,000 students each year, but only about 100,000 of those go on to become doctors. The rest enter research, biotech, or other higher-paying disciplines. TCM doctors make up about 10% of doctors in China.

Most physicians are public-sector employees, working in strict hierarchies within public hospitals and without much autonomy over their work. The vast majority are specialists. In urban settings, general or family medicine is not as common as in other countries. In 2016, there were only 206,000 primary care physicians in all of China. Lower salaries and lower social standing contribute to the dearth of primary care physicians. The Chinese government is currently encouraging more physicians to become general practitioners, including lowering barriers to enter GP practice and strengthening GP education in public medical schools.

As with many countries, in China there is a substantial urban-rural maldistribution of physicians. In urban areas there are about 4 doctors per 1,000 people, but in rural areas this falls to 1.7 per 1,000 people.

Far more common in rural areas are village doctors, who follow in the midcentury tradition of the barefoot doctors. They are only permitted to practice in village clinics, where they take responsibility for almost all primary and preventive care at the village level. They receive training in basic medical and paramedical treatment. In 2017, there were 968,000 village doctors and assistants working in 632,000 village clinics. About 93% of villages have a clinic, which is often the only accessible health care provider.

Doctor salaries range widely depending on location, experience, place of practice, and specialty. Salaries rarely exceed $30,000 USD (203,000 RMB) a year, and typical salaries are far lower. In reality, however, doctors often take home bonus pay because of kickbacks for prescribing certain drugs, fees from private patients, and even bribes from patients, so called red envelopes. These kickbacks have added to the perception that doctors are corrupt. As a result, violent physical assaults on doctors, usually by patients or their families, occur regularly.

Nurses

The supply of nurses has grown rapidly in the past 2 decades. In 2000, there was only 1 nurse per 1,000 people. By the end of 2017 that number had grown to 2.7 nurses per 1,000 people, or 3.8 million total. However, the supply of nurses is still quite low relative to the size of the population, the number of hospital beds, and international standards. Consequently, there is a high nurse vacancy rate in most hospitals. In addition, nurses are concentrated in urban areas, contributing to the shortage of providers in rural areas. In cities there are 5 nurses per 1,000 people but only 1.6 per 1,000 in rural areas.

Aspiring nurses are required to pass an examination (held once a year) and obtain a professional nursing certificate from the government. This requirement is waived for those with certain nursing degrees. Registered nurses are regularly reviewed and required to sit for an examination each year to keep their certificates.

Nurses have somewhat limited roles. Unlike in the Netherlands, for example, they cannot stand in for doctors in simple procedures. They administer tests, shots, and medicines; observe patients and maintain the medical record; and answer questions from patients and their families. However, they typically handle large patient loads compared to nurses in other countries. They are also not paid as well as nurses in many other countries. The typical salary for recent nursing graduates is as low as $300 USD (2,032 RMB) per month. As a result, nursing is not a highly regarded profession in China.

CHALLENGES

China has made tremendous leaps in relatively little time toward establishing national access to health insurance for 1.4 billion people through 2 insurance programs. Although gaps in access and out-of-pocket costs relative to income are much larger than in most Western high-income countries, 95% of the population has some form of health insurance. But, because of its size and political history, the Chinese health care system faces a number of unique and substantial challenges, especially in the delivery of care.

First, the legacy of the one-child policy has broad implications for social policy writ large. Without an adequate number of young workers contributing to the social safety net, health costs will rise as the population ages and fewer workers are contributing to the insurance funds. This problem is exacerbated by the increase in the prevalence of costly chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension. The one-child policy also exacerbates the problems of long-term care. Traditionally, adult male children and their wives cared for the husband’s parents in their old age. But the one-child policy gives each adult couple 2 sets of parents to care for, which will strain the younger generation’s resources. Informal, family-based care is no longer a sustainable solution for this growing elderly population. China urgently needs to address long-term care insurance and infrastructure.

China’s large and rapidly growing middle class is beginning to demand better medical care as well. But its health care delivery system is the most hospital centric of all the systems I studied. It is very expensive to build and staff new hospitals to meet the middle class’s rising expectations for high-quality care. And it is far more expensive to deliver care in a hospital than in a physician office, clinic, or community health center, which makes combating widespread diseases all the more challenging. Yet China faces serious barriers to moving more care out of hospitals into physician offices and clinics. This would require encouraging more—and more prestigious—physicians to provide clinic- or office-based care. In part, this could be incentivized by raising salaries for nonhospital primary care and specialist physicians. It may also require having physicians who want to practice in hospitals to also practice part of the time in nonhospital office settings. The mismatch between the populations’ rising expectations for high-quality health care and providing care predominantly in the hospital will be difficult to resolve given the current system’s structure and financing.

A related challenge is how China can introduce more private enterprise into health care. An aging population and the costs of building new hospitals mean that government financing and provision of health care and long-term services will be difficult. One possibility is to introduce more private-sector insurance and delivery of care. Not only might this relieve the government of meeting rising expectations; it might also allow more innovation in the Chinese system. The government, though, seems ambivalent about greater privatization of the health care system. The government’s hesitancy of permitting more private health care—and the threat of cutting down whatever emerges—makes it hard to see how a private system can flourish.

The difference in access to care between rural and urban areas also continues to be a challenge. Resources, institutions, and personnel are very unevenly distributed, creating substantial shortages in more rural areas. There are about 4 doctors per 1,000 people in urban areas, but this falls by more than half in rural areas. This maldistribution is even more extreme in the Tibet Autonomous Region and other areas mostly composed of ethnic minorities, like Xinjiang, where quality health care is hard to find. The government needs to incentivize physicians and nurses to move to rural areas as well as to invest more heavily in primary care and GP training, which is more mobile and cheaper to bring to rural areas.

Most troubling, however, is the lack of trust between doctors and patients. Health care—especially public health—requires trust that the system and physicians are acting in patients’ best interests and do not need to be bribed to do so. One source of the distrust is both real and perceived corruption in the Chinese health care system. For decades, doctors have been allowed to receive kickbacks from pharmaceutical companies while simultaneously upcharging patients for the very same drugs. Although new laws forbid these practices, both researchers and the public believe that they are still fairly common. Years of corruption have bred mistrust. The ultimate expression is the common violence against doctors and nurses committed by patients or their relatives dissatisfied with their care or its price. In addition, recent rumors that the government is using compulsory health exams to collect DNA to track minority populations further undermines trust. This lack of trust may have the most adverse impact in a public health emergency, as we have seen with the recent coronavirus outbreak. Because of the government’s tendency to understate the magnitude of public health crises, patients have not trusted the public health advisories, and the government’s suppression of crucial information about the virus’s spread has only fostered more distrust. The government needs to build trust in the medical system by making and rigorously enforcing laws to root out corruption. But to have physicians and nurses adhere to these laws and refuse bribes, they will have to be paid much better. This will raise costs.

The Chinese household registration (hukou) system in which people are registered in a municipality even if they live and work in far-off urban communities also continues to limit access. Merging URBMI and NCMS will certainly ease some of the issues that rural-to-urban migrants faced in obtaining care, but these issues will not be completely solved until the household registration system is abolished.

Relative to most high-income countries, China lags substantially in mental health care. Like other care in China, mental health care is still hospital based, and resources are unevenly distributed. Mental health disorders are also highly stigmatized in Chinese society; researchers have estimated that fewer than 10% of people with diagnosable mental health disorders seek treatment. As a consequence of the stigma there is a tremendous shortage in mental health personnel. As chronic care becomes an increasingly large portion of health care spending, China will need to address comorbid anxiety and depression, and the government needs to be working harder to create more resources for those in need as well as destigmatize mental illness.

The structural problems in health care are exacerbated by the administrative decentralization. Although from the outside China looks very centralized, with a command-and-control economy, the reality in health care is quite different. Provinces have substantial autonomy over funding, coverage, and prices. This means the central government has difficulty managing costs and transforming practices that inhibit progress. And, because most provinces are either primarily urban or primarily rural, they face fundamentally different structural challenges and funding.

In addition, the last 20 years have brought dozens of different health reforms. In the last 5 years alone, the government has merged 2 major public insurance schemes, overhauled the drug pricing and approval process, moved oversight of health insurance to a new government agency, and abolished the one-child policy. It is hard to evaluate the effects of any one of these changes when they occur in such quick succession. The system needs some stability to allow doctors, patients, and administrators to effectively implement and evaluate the new programs.

The demands on the Chinese system are immense. It needs to serve more than a sixth of the world’s population. Although it has achieved an impressive feat by providing health insurance to almost its entire population through 2 health insurance schemes, it also faces unique—and hard-to-change—structural, cultural, and behavioral barriers in delivering high-quality care. The system is excessively focused on hospitals. The population thinks high-quality care can be delivered in Class III national hospitals. The demand for such hospitals will grow as the middle class expands—and it is almost impossible to meet such demand even with big investments. Low trust in the health care system is pervasive because of corruption and other factors. Restoring trust requires increasing physician salaries and changing physician practices. Because of the one-child policy, China has grown old before it has grown rich. The demand for long-term care will put a huge financial burden on families and the government.

To confront these fundamental structural problems, China will need innovation in both the financing and delivery of health care. Yet the system is not structured to foster innovation—or permit more of it in an entrepreneurial private sector. To truly reform and meet growing population demands for better health care services, China will need to change the structure of its health care system. That is no easy task, but the consequences of failing to act could have significant political and social ramifications.