three

sentiment and imagination

Perhaps of all of Villa’s biographers, Ramón Puente drew the best picture of the obscure years of Villa’s youth, stripping them of demagoguery, romanticism, and anecdotes fashioned in the image of the future “historical” Pancho Villa. Puente writes: “His history before the Revolution is rough, filled with cruelty and infamies; what beauty there was, was the countryside; what softened him was the sentimentality out of which he often acted; what gave him light was an imagination that sometimes radiated over those shadows and sought to transform the misery of poverty into happiness and to transform the greed and avarice of the rich into liberalism and a common spirit.”

One anonymous author, in one of the many pamphlets composed about Pancho Villa, asserted that there is no material available to write the first part of his biography but that the legends are useful because legends are not written about those who do not deserve them. John Reed insisted, “It is nearly impossible to obtain any exact information about his life as a bandit.”

When the narrator began this chapter, he was faced with a puzzle of more than 850 notes pertaining to the years between 1894 and 1910, the phase of the “outlaw Villa,” in which faulty dates, inconsistencies, alternative names, and ambiguities abound—all of which are repeated cheerily by a multitude of witnesses. There are few elements that bring order to the history of this period, anchors that allow us to sort out the chaos of Villismo’s competing versions. Moreover, there is a gigantic legend manufactured a posteriori. The theory of the legend (only those who deserve a legend have one) does not seem entirely unjust to me. But Pancho also deserves a history.

Following the narratives that Pancho Villa recounted for his biographers, in September of 1894, after shooting López Negrete, “He walked directionless for several days, almost without eating, drinking water from puddles, hiding in the foothills around Gamón.” Living on the run and hiding in canyons that, according to Ramón Puente, “bore terrifying names like Devil’s Canyon, Witches’ Canyon, Hell’s Canyon.” In 2004, this author visited the area and the canyons themselves are not so terrible, only the names, the loneliness, and the isolation . . . and the long distances one can travel before seeing a human face.

The adolescent knew they were looking for him, he felt that he was the victim of bullying and harassment. His clothes were shredded, he was shoeless.

His future friend, Nicolás Fernández, remembered, “After four months, well, they got him because he didn’t know anything besides San Juan del Río, and he didn’t know where to run.” Pancho would later say: “One day, because of my inexperience, I was seen by three armed men who I couldn’t fight. Taking all possible precautions, and inflicting all kinds of cruelties, they overpowered me and brought me to San Juan del Río, throwing me in the jail at seven o’clock at night.”

Doroteo Arango thought that the Rurales were going to shoot him because he had fled, but if they intended to do so, they were in no hurry. The following morning, they made him grind a barrel of dried corn for tortillas. But he hit a guard with the grinding stone and took off running. “I climbed the hill behind the jail in Remedio to escape, and by the time the chief of police was notified, it was too late to get me.”

There is a second version describing Villa’s first escape. His aunt Luz Arango, whose house adjoined the jail, asked for help from Eulogio Salazar. They threw a rope into the prison courtyard and Doroteo climbed the walls. For several days he stayed hidden in the house in front of the prison, covered by a pile of dirty clothes. Then he stole a colt and fled into the mountains where he spent “nearly the whole next year” in the area around the foothills of Gamón.

The very young Doroteo Arango, many years later, would tell different stories about the solitary months he spent in the Durango foothills: that he was captured by seven men, but because he hid a pistol under his blanket, he was able to escape when his captors were quietly cutting ears of corn. Or, at the beginning of 1896 while he was still in the Silla foothills, the Canatlán Acordada came after him, but he ambushed them in a place called El Corral Falso, “I opened fire, killing three Rurales and seven horses.” Or he moved into the Gamón foothills and stole a dozen cows, “I got twelve cattle,” and then set himself up in Hell’s Canyon where he spent the next five months, selling a portion of the meat to loggers who traded him for beans, tortillas, and coffee.

But we would do better to think about how a youth of seventeen or eighteen learned to survive the terrible loneliness, stealing cows, feeling the Rurales breathing down his neck, malnourished, constantly searching for water, trading here and there for meat and leather, probably unarmed, all the while awash in a suspicious stream of consciousness and inner monologue. To survive in such an isolated state, he would have had to learn to speak in a low voice. He had to learn to talk to himself and then learn to tell stories, the same stories he told himself and to the random people he came across, mule drivers, loggers, and others on the run. It would be two years of wandering and solitude.

During his time as a highlander bandit, he learned a lot about botany, plants that kill, and plants that cure.

I know herbs. I know which are edible and which can cure you: coyote’s tail to close up cuts, the simonillo plant to control bile, and corn silk for when your kidneys hurt from riding a lot; the tabachín flower cures cough, and the tumbavaquero root strengthens the heart; there are herbs that put you to sleep and others that cheer you up like liquor. After a sunny day, if you get a bloody nose, look for fresh spring leaves. I knew one plant that heals wounds by coagulating the blood, one that cleanses sores by sucking out the pus, and one poultice that calms a spooked horse.

What was Doroteo’s pre-Villista view of the world? What constituted boundaries for this adolescent who was enclosed in an extraordinarily limited environment organized around a dozen large haciendas that together held unimaginable social, juridical, and political sway? There were only a few villages, a hundred small ranches, the misery of peonage, a handful of judges, the fearsome Acordada, and the Rurales, police, and vigilantes that worked for the local hacienda owners as well as Mexico’s central authorities. A world with very few options, with wide expanses and distant horizons. But sometime later, in Chihuahua, his perspectives would open up.

In August of 1896, he joined Ignacio Parra and Refugio Alvarado’s gang, the Jorobados (the Hunchbacks). His friend, Jesús Alday, introduced him. “Listen, Güerito [. . .] We know how to kill and how to steal, we’re telling you, so you don’t panic.” But very little would frighten this eighteen-year-old character.

Ignacio Parra was a caudillo, a local strongman, who also hailed from the Canatlán region, famous for running with Heraclio Bernal, the mythical Rayo de Sinaloa (Sinaloa Lightning Bolt), perhaps the most famous social bandit in Mexican history. Parra was the sole surviving member of a group of five brothers who had either retired or died during twenty years of adventures.

Villa, according to Puente, who many years later would pretty up his description, recalled:

Parra, sizing me up as a young kid entirely without experience, only gave me mundane chores to do: I was in charge of taking care of his horse as well as that of his second-in-command, who went by the nickname Jorobado; I tended the fire, made coffee, grilled the meat, and he’d almost always send me on errands when we had to stock up on goods. In this way, I quickly learned how to distinguish between tracks made by lots of different things: tire tracks from various vehicles, snake trails, and marks left by animals. [. . .] I also took notice of the sky and soon learned to tell which way the wind was blowing, which clouds carried water, and which would pass by without the blessing of rain. I came to know the exact time of day by the sun’s height and was guided at night by observing the moon and the stars and, especially, the Big Dipper.

Alongside Parra’s gang, Doroteo climbed towards Las Nieves and Canutillo in the mountains of Durango. Then they worked their way around to Parral, Chihuahua. They had a run-in with “two-hundred” Rurales who chased them close to his native Canatlán. The gang took refuge in the sierra “the hills of La Cocina.” The Acordada didn’t have the heart to follow them. They were credited with an attack on a stagecoach from El Oro on October 21, 1896. Mule robberies and thefts from the mining companies followed. During this period, Villa recalled divvying up hands full of money. Doroteo sent financial support to his mother, paid for a half-blind poor old man to open a tailor shop, and went around helping out “whomever he could with what they might need.” During one of the many confrontations of this time, he took a bullet that left a mark on one of his nipples. He renewed his connections with the man who had given him the burro and gotten him out of prison, Pablo Valenzuela, possibly using him to sell the merchandise he stole.

Most likely, it was during these years that he came to Mazatlán, in Sinaloa, “where I got to see the ocean for the first time, which made a big impression on me.”

Towards the end of 1897 or the beginning of 1898, Doroteo got in a shoot-out with Refugio Alvarado, claiming that Alvarado insulted him. Alvarado left the gang and died soon after in a gunfight in the badlands of Ocotlán. Sometime later, the young Arango split with Parra. It is said that they had words because Parra killed an elderly bread vendor in the street, which seemed absurd and brutal to Doroteo, more brutal than normal. Many years later, Pancho confessed to Antonia Díaz Soto y Gama, “At the beginning, my heart had not been hardened.”

Parra died on November 24, 1898, cornered by the Rurales. They cut him down in a hail of bullets and then strung him up in Puerto del Alacrán. A popular corrido paid tribute to his death, trapped by the Acordada who “like hunting a deer/didn’t hesitate to shoot/until he hit the ground.”

Doroteo Arango, during these years, kept up sporadic relations with María Isabel Campa, a girl from Durango with whom he would have a daughter, Reynalda, in 1898. María Isabel fell off a horse and died shortly thereafter. Doroteo sent money to María’s parents to support his child.

He moved closer to the area where his family set themselves up in Río Grande. He went back to rustling and used the aging Retana’s house as a hideout. He utilized Pablo Valenzuela’s store as a bank and sold leather and dried meats from there. In the La Silla region, in the environs of Satevó, he befriended Manuel Baca and Telésforo Terrazas and became known as el Güero (the fair-haired one). “He was very humble and obliging, but very gruff when it came to explaining his plans and ideas,” said Miguel Nevárez from Santa Clara. On November 1, 1899, the political boss of San Juan del Río claimed that he had spotted two bandits, Doroteo Arango and Estanislao Mendía “who were on their way to Guagojito [sic] where they had family.”

Jesús Vargas placed Doroteo Arango’s activities (both solo and with his partners) at the beginning of the nineteenth century, to the north of where the Parra gang had operated, including “Villa Ocampo, Indé, Las Nieves, Santa María del Oro, Guanaceví, Providencia (all located in the state of Durango) as well as Santa Bárbara, San Francisco del Oro, and various towns in the regions of Balleza, Huejotitlán, and El Tule.”

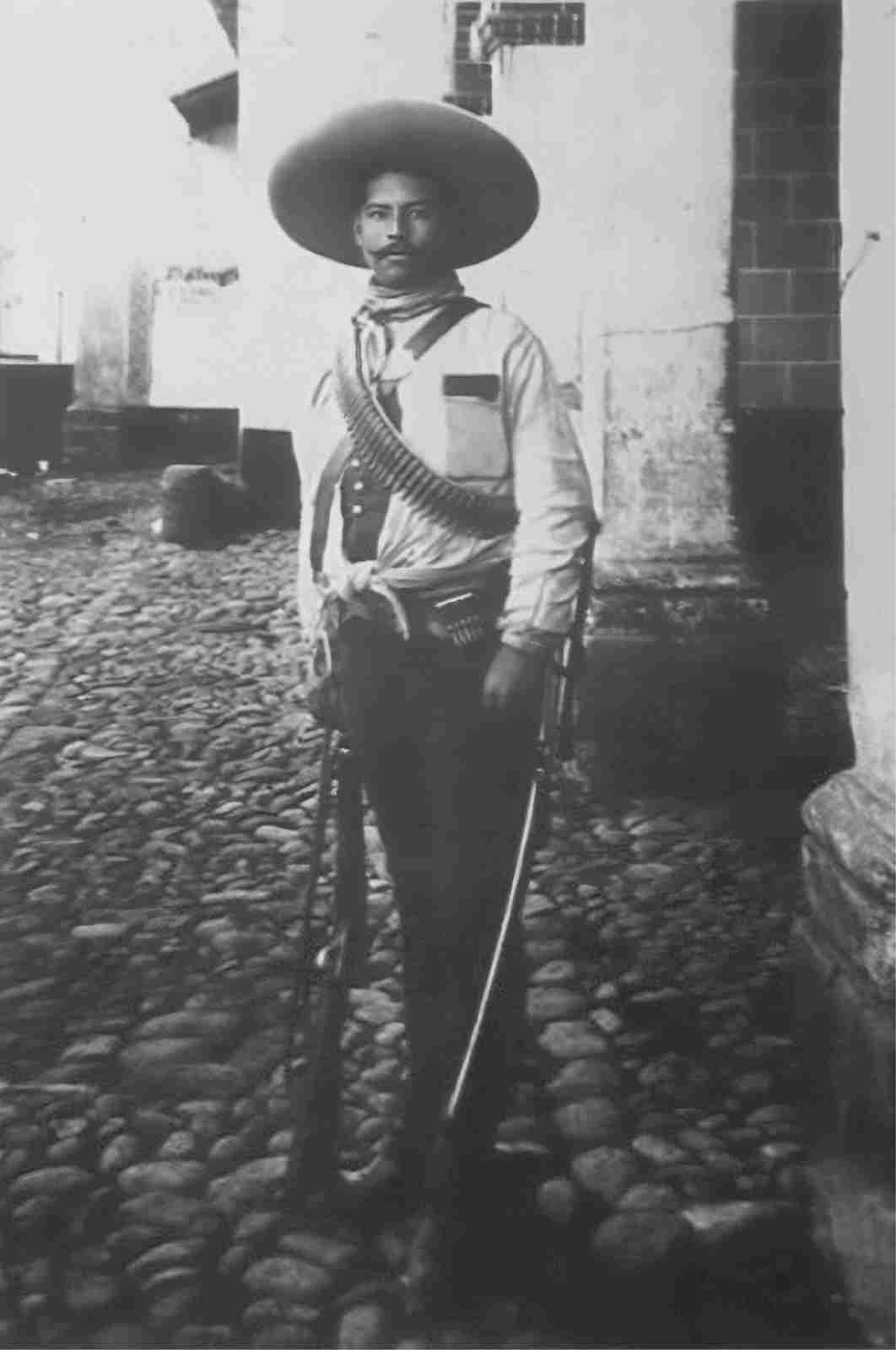

There is a photo of Doroteo on horseback sitting straight up. A crumbling brick wall stands behind him. Smiling, a thin mustache, bushy eyebrows, thin curly hair like a sheep, dressed in a jacket and white vest, a rope and rifle hanging from the saddle. A preview of the future Villa, missing only his band of brothers. “Villa at twenty-two years old,” says the negative’s caption.

At the beginning of 1901, Arango was captured by the authorities, accused of stealing burros and the goods they were carrying. They were going to deliver him to Octaviano Meraz, the chief of the Durango gendarmerie, but the judge ordered him to be taken to Canatlán instead, probably saving his life because Meraz was said to hang his prisoners first and investigate later. He was freed two months later owing to a lack of evidence. Katz suggested that Pablo Valenzuela, with whom Villa dealt in stolen cattle, protected him. Officials complained that el Güero belonged to the Mendía crew and that he would carry on as before, as soon as he was set free.

On March 8, Doroteo was once again detained for assaulting Ramón Reyes and stealing two rifles Reyes had been carrying or, according to another account, for having stolen a horse and killing Roque Castaño. He was handed over to the army, which was at the time gathering a levy of forced recruits. Montes de Oca believes that during this year in the youth’s life, after having been sentenced to death, he joined the army. The Honorable Florentino Soto, who presided over the case, submitted a pardon to the municipal president of San Juan, Manuel Díaz Coudier, in exchange for Doroteo joining the army to “fight the rebel Mochis Indians” in the neighboring state of Sinaloa where the central government kept bases in its extermination war against the Yaquis in Sonora. Vargas, Calzadíaz, López Valles, Guillermo Martínez, and Katz all described his escape on March 22, 1902, when he broke out of the Second Regiment’s barracks (or the Eleventh or the Fourteenth Regiment, according to different authors) and was then pursued as a “dangerous bandit.” Doroteo worked weaving bridles and winches for a certain Captain Plata, and as soon as he had enough rope, he twisted it together and escaped over the barrack’s wall. Did it really happen like that? This story seems suspiciously similar to previous tales.

After having escaped from the army, Doroteo left Durango and established himself on the outskirts of the city of Parral, Chihuahua, drawn there by the bonanza of silver and the booming cattle industry. Jesús Vargas recalled:

The voracity of the refining companies, their impunity, and their despoiling of peasant farmers and ranchers’ lands, who for generations had owned small properties, provoked a crack in local society that would rebound against the large landowners and their hoardings in the years to come. [. . .]. The bands of rustlers were just one part of a system in which judicial authorities, police, and government officials took part, including (and especially) respectable cattlemen who presided over stolen cattle, only to later supervise their sale.

It was at this moment that Doroteo Arango decided to call himself Pancho Villa. “When I arrived in Chihuahua, I changed my name to Francisco Villa to leave no trail.” Why did he take this name? There are a dozen versions, many of them from Villa himself who shared different stories with this or that listener.

Castellanos claims that he took the name Villa in memory of Agustín Villa, a man from his village, who had helped his mother while he was on the run. Villa’s cousins support this version. Nellie Campobello states that he took the last name from a relation of Villa Ocampo, Martín Villa. Villa himself reported to his biographers Puente, Martín Luis, and Bauche that “My father, Agustín Arango, was the biological son of Jesús Villa and because of his illegitimate origin, he took up the last name of his father who was Arango.” At any rate, upon taking the name Villa, he got his biological father’s name back. Benjamín Herrera said that the last name came from the actual son of a character named Juan López Villa. General José B. Reyes related how his godfather from Zacatecas, who was named Francisco Villa, had been there from the start and once asked Villa about his name, who replied, “I was wild when I was young and he taught me how to live among other people,” and for this reason, he took on his name. Montes de Oca wrote that, during Villa’s time in the army, he met a soldier with this name who was “very well known for his valor,” and when this soldier died, he assumed his last name. As is clear, there are many to choose from.

However, the most detailed and corroborated version is that Doroteo took his name from a bandit who was with him during the time he was in Parra’s gang. José María Núñez went further, arguing that he took the name because of the fame that accompanied the old outlaw to whom it belonged.

But this version doesn’t hold up. Francisco Villa (the first) hadn’t yet died when Doroteo was riding with Parra’s gang but only later when he fled to the United States around 1893. Furthermore, if Doroteo took the name to cover his tracks, to go underground, to distance himself from his past, to establish himself in a new region, far removed from his previous fame as a bandit—and outstanding legal charges—why would he have taken the name of a semi-famous gunman?

However tempting any of the seven aforementioned reasons might be—our information is foggy, having both too much and too little—the reality is that the name Pancho Villa would become one of the names that stuck with him and, little by little, attached itself to him until he made it his own.

It wasn’t the only name he would use. Nellie Campobello remembered that an uncle told her that when he was working in a mine near Las Bocas (Villa Ocampo) he met a man who went by the nickname Gorra Gacha (Shady)—who picked up the name because he would pull his hat down over his eyebrows when he didn’t trust the person to whom he was speaking—along with two other men who took to cooking dried meat. Gorra Gacha was none other than Villa. Nellie’s uncle—who was undoubtedly happy to pass along this intimate knowledge to the writer—described him as a man “with no name, only a rifle, a horse, and an old hat.”

Whoever it was who gave him the name, it’s clear that at this point in his life, he used it infrequently, while employing other names and nicknames depending on where he was and what he felt like going by at the time. Aguilar Mora, relying on “well-informed” information, put forward a more precise formulation when he wrote, “His name was an empty space which functioned according to his needs and passions at any given time, whether it be to ingratiate himself, to assume a belligerent pedigree, or to restore the legitimacy that was denied to a bastard father [. . .]. A multitude of identities lived behind this mask, a turbulent commotion of faces.”

It also might be that moving north and changing his name was part of an attempt by Pancho Villa to leave banditry and his easy-going but ruthless gun-toting life behind when he arrived in Parral towards the latter part of 1902 with his friend Luis Orozco, who would soon abandon him. The newly minted, twenty-four-year-old Pancho Villa worked as a construction laborer in the Plaza Juárez and used this name when he signed on the dotted line. Sometime later, he got a job working in the El Verde mine. But he was forced to leave the job after he developed gangrene in his leg from a poorly treated mining accident. While he was injured—in fact, he almost died from a blood infection—he found himself with no money and was going hungry, so he had to sell his horse, his hat, and his rifle. Things got so bad that a doctor wanted to amputate his leg, but some elderly ladies intervened and cured him using herbs.

While he was getting back on his feet, Santos Vega, a modest landowner, lent him $20 pesos (a tidy sum at the time) for food and to buy a mason’s trowel and gave him a job even though he was still limping and worn out from his long convalescence. Other sources claimed that he got a job as a bricklayer with Ismael Rodríguez, the owner of a small brick factory and that Pancho was in charge of mixing up the mud.

A variety of stories place him as a miner in different parts of Chihuahua. Many years later, the controller for the Santa Eulalia mines would remember that Villa worked in several locations such as Mina Vieja, Gasolina, and la Velardeña. It was said—although it seems likely to be a story concocted after the fact—that during this time he came to know one of the richest mine owners in the world, Pedro Alvarado. In Alvarado family lore, Villa asked for a job in the La Palmilla mine and worked as a miner for several months before taking ill, and that Alvarado helped him get by until his health improved.

Villa’s short-lived time in normal society quickly came to an end. Sick of being a legal proletarian, living the poorly-paid, hard life of a miner or mason, he decided to go back to no-man’s-land. Whether for these reasons or as Villa told it—because the police were investigating him—he decided to flee with his compadre Eleuterio Soto, who went by the nickname el Sordo (the Deaf One).

At some point during these months, Villa’s mother died. He recounted this story many times over the years in at least five different versions, each one with its own variations.

After learning from one of his brothers that his mother was very ill, “I left for Santa Isabel seeking her final blessing [. . .] accompanied by a trusted friend who waited for me at a nearby ranch.” He brought her $200 pesos. On one occasion he said he found his mother in bed surrounded by candles and by so many mourners that he could not see her. Another time he said that while he cried, he kissed her body’s hands. Or “I could only see her from the doorway leading to the street where so many people had come to mourn her.” Or “imagine how bitter I was upon passing through the door of the ranch to see my poor mother being mourned, that I fell to my knees and cried like a little kid. When I kissed her stiff hand, I heard voices outside yelling, ‘Get him!’” Or “just as I was about to dismount my horse, I heard someone yell, ‘Get him!’” In the end, Villa remembers pushing his way back to his horse, a pistol in each hand. “During the commotion, I knocked over two bald guys.”

According to what he would recount many years later, he wandered aimlessly through the sierra, drenched by torrential rains. He’d never seen such powerful lightning before and if the Rurales had been following him then, they would have found him because the lightning lit up the hills. He took shelter in an oak grove and asked himself in tears (in the version he related to a Dr. Ramón Puente some years later) “Why can’t I be like other people? They have their own sorrows, but they live happily with their own people.” In the morning, his horse jolted him awake because he had tied the bridle to his ankle. He heard some mule drivers hauling cattle and “went away, far away.”

Over those years, he had learned to read and write rudimentarily. He learned to write his signature by copying the drawing of his signature that another person had written for him. “I kept as many documents and papers on hand as I could and guarded them carefully so that someone more fortunate than me could decipher them for me. I wrote in the sand, in the dirt, wherever and whenever I could I found time to practice my unsteady handwriting. When I was twenty-seven years old, I experienced one of the greatest pleasures in my life when I managed to puzzle through the letters on a sign one day and I realized it was talking about me. I always carried a stack of written papers with me, no matter the subject, which I used as models to spell by.” Villa told this same story to a North American journalist sometime later, although claiming he was slightly younger. “I was twenty-five before I could write my name.” Villa’s testimony is supported by the mountain folk of Namiquipa who said that he could barely read and write at that time.

Villa remained active in the Parral area, establishing a business and personal relationship with Miguel and Quirino Baca, a.k.a. Vaca, who bought stolen cattle from him and traded them. He became friends with Gorgonio Beltrán, a Yaqui Indian, as well as with the Trinidad brothers, Samuel and Juan Rodríguez, who both had charges pending against them in Hidalgo for cattle rustling. Many years later, a newspaper in the United States reported an accusation that “a man named Arango,” but going by the name “Villa,” had shot Rafael Reyes, a wealthy Parral local and enemy of Miguel Baca Valles, in the back. The authorities launched an investigation, but Villa had already made his getaway.

He went on changing his name like other men changed their shirts. He bought a house in Balleza using the name Salvador Heredia and sold stolen cattle in Valle de Rosario going by Antonio Flores.

At some point during this period, Villa encountered a new and singular character, a certain Tomás Urbina, whom he met in San Bernardo, Durango, and teamed up with him to steal cattle from large haciendas. Eleuterio Soto and Sabás Baca came along for the ride.

Urbina was a mestizo Tarahumara Indian from Congregación de las Nieves, Durango, who was eight years older than Villa. He was the son of an unknown father and Refugio Urbina Reyes, from whom he took his last name. Starting from his early years, the illiterate youth worked on haciendas as a laborer and later as a brickmaker and adobe house construction worker, getting paid every other week or by the month. In the summers, he made bricks and built houses, but in the winter, when construction work dried up, he dedicated himself to cattle rustling. In 1896, he married Juana Lucero. Along the way, he took “many lives,” including a Spaniard named Ramírez from Canutillo. Nellie Campobello, who always had a way with words, claimed that “the sierra, sotol, and the Acordada” made them that way . . . sotol being a cousin of tequila. She would add that Urbina “was looked after by the holy infant of Atocha” and described him as a “man in tight black pants, a cowboy shirt, and a large hat.” Vito Alessio Robles summed him up with three adjectives: “mean, surly, and hostile.” John Reed, who met him years after, completed the portrait, “He was a formidable, medium-sized man of dark mahogany complexion, with a sparse beard up to his cheekbones, a wide, thin, expressionless mouth, gaping nostrils, and shiny, small, humorous animal eyes.” Urbina would remain Villa’s closest friend, associate, and compañero during these years.

Of all the anecdotes from their time together, Villa loved telling stories about what a heavy sleeper Urbina was. Once, the Rurales pursued them for a whole week without rest in the foothills of Durango. “No matter how long we rode, the Rurales would appear again and force us to resume our arduous journey [. . .]. The horses were falling down from fatigue. My compadre Urbina, more and more exhausted, managed to stay alert as long as he was in the saddle [. . .]. Finally, one morning we felt safe [. . .] on some high ground like a watchtower.” They agreed that Urbina would sleep first for two hours and then Villa would get his turn. Urbina was dressed in a rose-colored shirt that was missing the top button. All of a sudden, the Rurales appeared, and Villa tried desperately to wake up his partner, but it was impossible. “I grabbed his head and shook him roughly, but he kept sleeping just the same.” Villa started to saddle up the horses and, in desperation, fired two shots next to Urbina’s ear, still nothing. He ended up tying Urbina to his horse and escaping through the hills. Urbina kept on sleeping through the entire getaway.

Over the next couple of years, a multitude of attacks and robbery attempts were attributed to the pair. For instance, Villa and another man held up a jeweler from Parral named Dehlberg as he closed up his shop for the night. They stole pens and watches, but the most valuable jewels were locked in a safe and they couldn’t get to them, so they cut the jeweler’s neck. They were caught a couple of weeks later trying to sell the watches, but they managed to escape.

In December 1903, in Valle de Allende, Villa’s gang (now including Urbina, Eleuterio Soto, Sabás Baca, and someone named Gallardo), were driving a herd of stolen cattle to sell to Miguel Baca Valles, who had a ranch in the vicinity of Parral. Suddenly, they were attacked from behind by forty Rurales who shot dead four of Villa’s gang and scattered the rest. The story goes that Villa was able to hide because he had a girlfriend nearby.

During those years, Villa hung out with Baca Valles’s mule driver in the Conejo neighborhood on the outskirts of the city of Parral. Baca bought stolen cattle from him at a quarter of their value.

Villa spent his time traipsing across the immense territory, alternating between “legal” jobs and banditry. That’s where we find him managing a butcher shop in Parral cutting up stolen cattle, which is how Pat Quinn met him when he was working as a cowboy on a gringo’s ranch in Chihuahua. “His job as a cowboy was just part time, among other things that I didn’t ask him about.” Around the same time, Antonia Fernández—along with Nicolás Fernández, who was the foreman for the Valsequillo hacienda and a ranch hand on the Terrazas hacienda—encountered Villa in the Galeana district as he led a gang stealing cattle from the Palomas hacienda. Rifle in hand, Villa demanded they give him a horse so he could flee the Acordada. This might have been the same escape in which he lost a hat he’d bought on credit from Guillermo Baca’s store in Parral. And maybe the same escape in which he met Maclovio Herrera and asked for water, food, and grass for his horse while being chased by a party of Rurales.

Starting in 1904, another leader of the group, an army deserter named José Beltrán, el Charro (the Cowboy), who earned the nickname because he rode a black horse and wore a silver cowboy outfit. The gang, which included Beltrán, Villa, Urbina, Jesús Seáñez, and Rosendo Gallardo, became well known for sharing their loot with the poor. They developed contacts all over the region from Parral to Santa Bárbara up to Guanaceví, Durango, and all along the northern part of the Sextín River, along whose waters they often set up to sell stolen cattle, mules, and horses. They were accused of having robbed the Terrero ranch in the Hidalgo district, where they injured a man named Sotero Duarte and his son, and later they pillaged a small town called Los Charios in Durango.

At six in the morning of May 21, 1904, in Villa Ocampo, a farming village of some fifteen hundred inhabitants and only two deputies, el Charro, Beltrán, Rosendo Gallardo, and Arcadio Regalado came to collect a blood debt from Gabino Anaya—an older wealthy man from the town who owned houses, a ranch, and cattle in the area.

Anaya had conducted business—the nature of which was neither very clear, nor legal—with Beltrán in the past. When el Charro had come to collect, Anaya refused to pay and, following a long-established practice by the rich who operated along the edges of the law, Anaya denounced Beltrán to the authorities who locked him in jail, then a stockade, and, finally, drafted him into the army. Now Beltrán was back.

At six in the morning, Beltrán and his group demanded $10,000 pesos from Anaya, which el Charro was owed from their old dealings. They apprehended him and hung him from a tree together with his nephew Francisco Aranda for the whole day, until six or seven in the evening when Don Gabino’s wife came out and told the gang to let them go because she would tell them where her husband kept his money. They lowered them down from the tree in exchange for her handing over the keys when, by pure chance, a police officer passed by and realized that something strange was taking place. He entered the house and, from a well-protected position, started shooting. Reinforcements arrived. The bandits fled. Two Rurales were injured in the shoot-out, the chief of the Acordada was hit in the hand and a policeman named Braulio Soto was hit in the stomach, dying the following day. Gabino Anaya had better luck. He suffered fifteen stab wounds but ended up surviving.

Nellie Campobello’s uncle witnessed the bandits during their escape: “They arrived splattered in blood, weary, believing that they had killed Don Gabino, and they were hungry. I gave them dried meat and flour gorditas. They talked and ate and put me in charge of waking them up before sunrise. They tied up their horses and fell asleep. By the time the sun was starting to come up, the Acordada search parties were already looking for them, but the bearded outlaws hadn’t yet woken up. I crawled over to the first one on my belly and shook him. They took off in a cloud of dust.”

As the case had gained wide notoriety in the press, the acordadas from Indé and Parral joined forces to organize a large posse in which they captured Rosendo Gallardo and tracked down Elías Flores in the waters of the Magistral River, whom they shot without any pretense of a trial, even though he had nothing to do with the matter. Later, in the environs of the Rueda hacienda, they also came across a member of the gang who had not participated in the attack on the Anaya house, Jesús Seáñez, whom they dispatched in the same manner.

Some months later in 1905, the gang dared to enter Parral itself. Beltrán met with Villa and the other members in the Las Carolinas saloon in an act of bravado in disdain of the Rurales. Ismael Palma, the chief of the local Acordada, denounced him and had him surrounded by several of his men. Beltrán fought with heart and soul but was caught alone and died riddled with bullets. Villa, who arrived sometime later, heard the gunshots, and managed to escape. Beltrán’s funeral took place as the afternoon sun turned the light to bronze, as they say, while Villa watched from afar.

The group made one more assault on an hacienda named La Estanzuela, where they killed a US citizen, his wife, and their maid as they were eating in their living room. Later, with the Rurales in the area on edge, the gang scattered, and Villa headed towards the northern part of the state.

Perhaps Villa returned to “legality” during this part of his life, working for a time as a subcontractor for the Chihuahua-Pacífico railway, selling and renting packs of mules for railway contractors, and transporting food to various railway construction sites. Sometime later, Villa reported being put in charge of the $700,000-pesos payroll for the Northwest Railway and the mines, while on another occasion he was responsible for thirty-six bars of silver and six bars of gold. There’s no doubt that, when Villa wasn’t robbing and stealing, he was an honest man. And although this might sound absurd, it’s consistent with his personality.

Roberto Fierro reported seeing him as he transported mules from Durango, “Extremely strong, red-faced, and sunburnt.” This was during the time when he met Albino Frías—most likely at the end of 1905 or the beginning of 1906, when he crossed the border to the US—and, as Ramón Puente reported, worked in New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona in the mines and the railway yards.

However, we also have a report from an army major who stated that he was in pursuit of the bandit and gang member Pancho Villa during 1905 in the area between Juárez and Las Orientales (one hundred kilometers to the southeast of Ojinaga) up to Galeana, in the hill country in the northern part of Chihuahua, and that, despite confronting him on several occasions, the major had suffered various misfortunes because Villa was “very clever.” Around this time, an American newspaper situated Villa in the village of Álamos de Cerro Gordo, in the Hidalgo district of Chihuahua, reporting that Villa killed a farmer named Ramón López—who had been returning to Parral to sell a wagon full of cheese—and robbed him of $800 pesos. He then committed several minor crimes in the same area going by the name of Rayo Saucedo. There is also a story that he and a partner were caught butchering a stolen steer they had taken from the Bustillos hacienda, owned by the Madero-Zuloaga family in the central part of the state. He was arrested and put in jail to be handed over to the Acordada, but one of the hacienda owner’s children saved him, telling his father to let him go because he had done what he did out of hunger. This episode created a friendship between Villa, the hacienda owner, and his wife, Doña Mercedes, that lasted for the rest of his life.

Whether Villa was in the northeast, or in the south, or in the middle of Chihuahua, he covered a thousand kilometers of rough roads on horseback. Or maybe he was everywhere at once, a very common theme throughout this story.

But what all these fragments make clear is that he established himself in the city of Chihuahua, the state capital, during 1906. He first developed a relationship with the Rodríguez family who ran a store, coming to an agreement with the owner to safeguard a certain amount of money. Sometimes he even slept behind the counter. Later he rented a place from Nicolás Saldívar on Décima Street in the Puerto de San Pedro neighborhood on the outskirts of the city, a fenceless lot with a three-room adobe cottage. Saldívar worked as an independent butcher who slaughtered cattle in his own house instead of a slaughterhouse and conducted business with Villa who brought him cattle. There, Villa learned how to make saddletrees and had a girlfriend named Herminia Zaragoza, a fifteen-year-old girl to whom he presented little cakes he bought from Francisco Torres.

Aside from living in Chihuahua, he came and went from the city, carrying out strange business dealings and enduring wild financial ups and downs. One time, he showed up at Saldívar’s house with a pair of shoes he’d bought for his son for $10 pesos—he only paid $4 pesos, later settling the remaining debt during one of his trips. Villa then passed by Nicolás Rodríguez’s house which had a grocery store on the first floor where he would sometimes sleep. Nicolás saw him there writing notes, “Pancho was not illiterate since I watched him writing messages a million times on the store’s counter.” But what he was really good at was adding and subtracting, he could multiply as well, and he even knew how to calculate interest.

In any event, Villa continued to combine his legal activities with robberies and trafficking in cattle, relying on a commercial relationship with, among others, the Abraham and Santiago González brothers, who delivered cattle to the Chihuahua slaughterhouse.

In 1906, Villa bought the land under the shack on Décima Street. A wide plot on which he had “rented a three-room, whitewashed adobe dwelling with a small kitchen and large corral for my horses. I built the walls myself to enclose the paddock as well as the stalls for the horses along with a luxurious water and feeding trough.” They say his house was “a hangout for cattlemen, butchers, and wandering horsemen, who came and went at all hours.” Puente described the house, “Half-built, a wreck with miserable furnishings, but there were saddles and rifles and plenty of horses in the corral.”

There’s a photograph from those years in Chihuahua. A thin, elegant Villa is wearing a three-piece suit with a cowboy jacket, boots, and a tie, sporting a thin mustache, a flower in his buttonhole, his right arm resting on a shelf; curiously his hair is combed, and he is bareheaded. It was taken during his time as a businessman after he had opened a butcher shop. “A year spent honorably killing cattle in the city’s slaughterhouse and then selling the meat in my small shop.” But local officials got their claws into him, taking money and pressing him. And there was too much “legal” competition sheltering behind shady deals, bribery, and the authorities’ outstretched hands. He handed the business over to José Saldívar and unexpectedly returned to the plains and the hills of his native region, Durango.

On March 6, 1907, a Chihuahua newspaper reported that authorities were pursuing a gang composed of Gumersindo Ortega (a former mounted deputy), Sotero Aguilar, Doroteo Arango, and José Gallegos, which was “prowling between San Juan del Río and Canatlán and had committed several armed assaults. It appears that the locals are protecting them.” In subsequent editions, the paper noted that the gang was dissolved after its leader Gumersindo Ortega was killed in a confrontation with the gendarmerie and Rito Pérez was captured. José Gallegos hid in the mountains, but his father claimed he would turn himself in. Sotero Aguilar and Alejandro [sic] Arango “fled in the direction of Chihuahua, believed to be on their way to the United States.”

On November 5, 1907, the official in charge of the city of Durango submitted a request to his counterpart in Indé for the capture of the bandits Matías Parra, Sotero Aguilar, Doroteo Arango, Refugio Avitia, Cesáreo Díaz, Salvador N., and José Gallegos—who, it turned out, had not turned himself into the police—accusing them of having stolen twenty-two mules and horses from the Salais ranch. He also pointed out that they had stashed their loot in the house of a woman of “ill repute” named Medrano.

The gang, as seems a frequent occurrence throughout history, broke up and Villa took off on horseback with his compadre. At the start of 1908, Villa and Urbina got in a gun fight that left hacienda owner Guadalupe de Rueda Aurelio del Valle and his friend José Martínez dead. Del Valle had contracted Villa’s associate Eleuterio Soto to do an illegal job and then, instead of paying him, denounced him to the police, a common ploy in those days. The authorities were going to shoot Soto but decided instead to conscript him into the army. Villa went around raising money to get Soto out of the army, succeeding after several months. They then went to collect the debt from the hacienda owner. Shortly after the attack, Urbina and Las Nieves were arrested, not in connection with this assault, but for stealing a cow. Once again, the authorities considered shooting the prisoners, but settled on whipping them. Meanwhile, Villa set himself up in Parral and when Soto was released from jail, they celebrated by stealing three hundred cattle from the Matalotes hacienda.

The three compadres, Urbina, Soto, and Villa were active in the region around Chihuahua where Villa’s El Fresno ranch was located and when things turned ugly, they moved up to the Sierra Azul Mountains where they built a small fort.

Ignacio Muñoz remembered much later that three people arrived in the town of Cruces in 1908 when he was working in a small store (Telésforo Terrazas, Manuel Baca, and one they called el Güero) and that they left money for a deposit with him for a steer that they would have to deliver later. The name Pancho Villa was on the receipt.

In future stories, constructed from fragments from the poor memories of dozens of witnesses, Pancho Villa disappeared and reappeared in locations that were hundreds of kilometers apart, so many places and so many sightings. Three bandits driving a herd of mules were brought to the attention of the Parral authorities and there was a shoot-out near Minas Nuevas where one of the injured outlaws, Villa, was attended to in secret by a humble family of the area. Frank M. King met Villa in the Dolores gold mines, the center of his mining operations, where he rented mule convoys in the mining district. Villa himself confirmed this story when he recounted walking by the waters of the Santa Eulalia—where he worked for a year and a half—with a manager named Willy. They called Villa el Minero (the Miner). His “untiring Durango persecutors” located him and Villa fled into the mountains “no horse, no pistol, no rifle” and “hid like a cat” in Miguel Baca Valles’ house in Parral. Rumors circulated that he added a new scar to his collection during a narrow escape.

In 1909, the group robbed the Valsequillo ranch, owned by the widow Marcelo Guerra, in the Hidalgo district; and in August they attacked Valle del Rosario, where they burned town records. Villa himself stole the municipal seal, which he would later use to legalize fake papers certifying cattle ownership.

During this time, he kept up a relationship with Petra Espinoza (or Petra Vara), a twenty-eight-year-old Parral woman (Villa was thirty-one) whom he first kidnapped and later married. Rosa Helia Villa, Pancho’s niece, described her as “beautiful and uninhibited, with a tempting body.”

Around 1909, Julia Franco, a teacher in Santa Inés, recalled that when a horse and mule seller entered the town, the people gathered around to bargain. Then the man challenged the locals to a shooting contest, so they placed different objects on the branches of an oak tree. She heard someone say, “No kidding, that Pancho Villa is good with the rifle.”

M.L. Burkhead, who owned a car dealership in El Paso, Texas, met Villa and dealt with him along the border. He hired him for $3 dollars a week to help him run a cockfighting business. Three years prior, in Chihuahua, Villa had already demonstrated his talent in this sport.

In March 1910, Antonio Flores carried out an assault on the Santa Rita ranch in Valle de Rosario, near Parral, and robbed the Flores widow of twenty-eight head of livestock, which were later sold to a Sidronio Derat. Maybe the most notable detail of this story was the precise, picturesque, and badly-spelled description of the stolen animals: “2 dark colured oxes, 2 black spackled oxes, 2 moor oxes, 2 golden oxes, 3 dark-colured oxes, 3 canary golden oxes, 1 cowe with tan legs, 1 chestnut cowe, 2 black cowes, 2 dark colured cowes, 1 dark-colured chestnut oxe, 1 spackled black cowe, 2 black colured oxes, 1 spotted oxe, 1 black oxe with a wide fase.”

The police, following up on a lead, detained a certain Alfredo Villa, accused of having raided the Talamantes hacienda, but witnesses claimed they had the wrong man. They interrogated Sidronio, who confirmed that the seller was Antonio Flores, but he couldn’t remember what he’d paid for the cattle. So, they hit on Jesús Vargas, who was supposedly Villa’s brother-in-law as he was married to Petra Vara, with whom he carried on a “steady relationship.” Jesús claimed that Antonio “had been away from his house for three or four days.” But when questioned about his ownership of a specific horse, he produced a fascinating letter that read:

Señor Jesús Vara. Dear Sir, I am writing this letter to greet you and your family, and now having offered you my greetings, I must inform you of the following, that is, I envited [sic] you here to Chihuahua but nowe [sic] I must tell you that I cannot be here untel [sic] May, I will send Petrita to look for you seeing that you don’t need anything else. I’m sending you the horse certificate nowe [sic] without further ado. Francisco Villa.

Comparing the letter with the list of stolen cattle, an expert judged that Antonio Flores and Pancho Villa were one and the same, and orders for his arrest were issued in June 1910. The police description of the wanted character went as follows: “Normal height, heavy build, light skin, dark brown hair and eyebrows, dark eyes, large forehead, regular nose and mouth, bushy beard with a light-colored mustache, married, twenty-eight years old, no visible marks.”

While all this was going on, Villa was hardly inactive and, after hiding for a time at the La Parra ranch, in El Tule, owned by Chon Yáñez, the gang raided the San Isidro ranch in the Hidalgo district. They killed the owner Alejandro Muñoz and his son and made off with a booty of a $1,000 pesos. Villa had presented himself at the ranch as a certain A. Castañeda.

On May 25, a new order for his arrest was signed, issued in San Isidro de las Cuevas, reading “Francisco Villa, whose name is Alfredo [. . .] for the crimes of robbery and homicide.”

While being pursued in the southern part of the state for cattle rustling and homicide, Doroteo Arango, a.k.a. Arcadio Regalado, a.k.a. Salvador Heredia, a.k.a. Pancho Villa, a.k.a. Gorra Gacha, a.k.a. el Güero, a.k.a. la Fierona, a.k.a. A. Castañeda, a.k.a. el Minero, a.k.a. Rayo Saucedo, a.k.a. Antonio Flores, a.k.a. Alfredo was not sitting still, moving from Chihuahua to San Andrés, from Ciénaga de Ortiz towards the northwestern part of the immense state. On June 23, 1910, a railway watchman detained Villa in Madera “for offenses committed by him.” The watchman took $250 pesos and a pistol off him but let him go free an hour later. It appears that Villa filed a complaint about his treatment because an official in Madera sent the political chief of Ciudad Guerrero a note in which he argued that there was nothing to Villa’s grievance and that “we treated him with every consideration.”

A short time after, Villa and Urbina helped themselves to sixty-two mules from the Torreón de Cañas hacienda. They were followed and engaged in a shoot-out at La Jabonera hacienda where the Rurales killed several of Villa’s men and recovered the mules, but the two compadres managed to escape.

By the middle of 1910, Pancho Villa was running out of pseudonyms and locations in which he could operate relatively safely, he was exhausting his hiding places, and had earned several scars. Sleeping in the mountains in the open air, subject to tremendous heat and terrible cold, and all the while suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, neither Villa’s fame nor the number of men under his command on the margins of the law were all that great. However, he had acquired a vast number of contacts and relationships up and down Chihuahua and Durango, wives and friends, people who owed him favors, associates and partners, and all sorts of allies in his misadventures. Their names included Tomás Urbina, the Yaqui Indian Gorgonio, Eleuterio, Trini Rodríguez, Maclovio Herrera, the Bacas, and Nicolás Fernández—and they would all play a role in his future history. He’d lived as a bandolero who, at times, put down his guns to work under the laws and social order enforced by president-for-life Porfirio Díaz, but circumstances, luck, accidents, and his own temperament prevented him from fitting in.

The portrait drawn up by Martín Luis Guzmán is not entirely fair: “He tried to be a worker, hiding himself to work in the tunnels, but he was helpless in the mines. He wanted to be an artisan, to become a mason, but the long arm of the law cornered him. He wanted to be a small manufacturer, to open a tannery, but the abuses of injustice obstructed his path. He tried to be a small shopkeeper, to run a butcher shop, but the market was crowded, and his armed persecutors would not consent.” It would seem, according to this picture, that Doroteo Arango, over the course of these seventeen years of living hand to mouth, had sought out legality but the darkest forces of Porfirian society had blocked his way. This doesn’t ring true to the story we have told up to now.

It’s true that Villa was a product of the darkest forces of Porfirian society, but not its superficial elements, rather the profound forces that condemned a poor campesino to a life in prison, to be nothing more than fodder for the great haciendas and the army, to be a starving worker in the new mines and factories. Pancho Villa reacted against all this, in a frantic yet determined manner, playing at life for seventeen years and grabbing it from others, cheating, stealing, sometimes from much bigger thieves than himself, sometimes from people almost as miserable as he was, and always searching for an individual destination that he never could reach, walking the line between the appearance of law and order, and disorder and banditry.

However, this history, as Puente reminds us, is “vulgar, filled with cruelties and infamies,” what was picturesque was the countryside, and “what softened him was the sentimentality which he displayed in many of his actions, “but all this would be understood differently as the years went by.” The myth of the extraordinarily popular bandit Pancho Villa grew among the campesino masses in northern Mexico. And they would determine what followed.

Cervantes wrote, “He was twenty-two as his fame spread across Durango and Chihuahua,” and “he was gaining acclaim all along the border.” Academic historians added sustenance to this thesis. Mark G. Anderson spoke of the “notorious bandit” who had achieved “preeminence and approval among the masses in northern-central Mexico,” and J. Mason Hart concluded, “The Mexican peasantry bestowed upon Villa the role of an honorable thief, a new Robin Hood who stole from the oppressive rich and gave to the poor.” Hans Werner claimed, “Starting as a cattle thief, he soon became the most famous bandit in the North,” while Eisenhower added: “He was a bandit for sixteen years. During this time, a legend grew among the people that he was a Mexican Robin Hood.” Even Friedrich Katz, in one of his first books, asserted, “He lived in the popular consciousness as a kind of Robin Hood.” And Ricardo Pozas remarked that Villa was “One of the most famous social bandits from this part of the country.”

When the US press began to take a real interest in him, his image came into focus. At the beginning of 1914, an article appeared in The Sun that stated: “Before the Revolution, he was a well-known bandit, the terror of the mountains, with a price on his head. Díaz and his soldiers had tried to capture him over the years.” This is the logic set out in the poem dedicated to Villa by Santos Chocano that goes: “You fall, you fall . . . divine bandolero [. . .]. A demon and an angel in stubborn rebellion/They fight over the hidden meaning of your intentions.” Not even John Reed himself escaped, “There are many traditional songs and ballads celebrating his exploits—you can hear the shepherds singing them around their fires in the mountains at night,” repeating ballads praising the romantic feats of Pancho Villa. “He was known as The Friend of the Poor. He was the Mexican Robin Hood.” As we have seen, nothing could be farther from reality.

During his days as a bandit, Villa never put forward a social program, he never considered changing the world beyond the range of a bullet from his rifle. He never led a large band of followers (no more than a dozen ever road with him), but neither did he join the Rurales or the Acordada. He wasn’t a hired gun for the political bosses nor the hacienda owners. Aguilar Mora—explaining why Nellie Campobello had no qualms about describing Villa as a bandit—said it best, Villa became “an expression, a sign of the oppressed, who recognized, like a weapon of war, the terms with which their enemy tried to degrade them, to entrap them, to exclude them.” But Mora’s is a voice in the wilderness.

What sort of pathetic conflict arises between the clean consciences of the many narrators and the history of the bandoleros? If the bandits were generous and friendly, historians can pardon them. But what if they were gruff and terrible and the violence they employed was brutal and very often arbitrary, guided by the logic of survival in which an injured enemy should be finished off so that he can’t come back to get revenge? If the gunslinger is dirty and bloody, then clearly, he can’t enter history.

Recovered and sanctified by Eric Hobsbawm in two of his books (Bandits and Primitive Rebels), the “social gunfighter” would be the exception. He would emerge as the crude but conscious representative of agrarian rebellion. And Hobsbawm himself fell into the trap, characterizing Pancho Villa as such, relying solely on the Memorias de Francisco Villa by Martín Guzmán as his documentary evidence.

However, one of Hobsbawm’s own reflections allows us to note a contrast, “Peasant societies distinguish very clearly between those bandits who deserve [. . .] approval and those who do not.” Villa enjoyed very little social recognition during his time as a bandit beyond a network that extended across Chihuahua and to the north of Durango. Villa’s network was composed of contacts, compadres, accomplices, associates, friends, and assorted beneficiaries who might have received a cow, a handful of pesos, or a sewing machine. His recognition was that of a person who changed names and locations, who disappeared for long stretches of time, and changed jobs frequently. He demonstrated little generosity towards the people on the receiving end of his actions. He robbed hacienda owners, but he did not challenge them; he killed Rurales, but he did not organize to destroy them; he robbed the rich, but very seldom gave to the poor. However, if he did not earn much social recognition over these years, he did build up a network and an ethic, set the rules of the game, and developed a hatred for the oligarchy.

A man’s word must be kept, never betray a compadre, don’t rob from the poor—unless it is absolutely necessary, besides, there’s not much to steal—don’t rape women and, if you seduce one, you must marry her (perhaps even several), either in church or in front of a judge. Neither the rich nor the priests deserve respect, but teachers do. Take care of children. Along with this ethic, Villa created a style: change your name like you change your hat, if you sleep in a house, make sure it has a patio and a window for a quick escape, don’t fall asleep in the same place you wake up, your horse should be ready, your gun loaded, and you should show up where no one expects you.

In a society in which the great hacienda owners exercised the right of the first night, where they punished infractions with the lash, where they robbed communal lands using fake boundaries, where they trampled over historical rights to pastures and water; in which the Rurales and the Acordada were hired guns with no more of the law on their side than the men with whom they clashed; in which a man in debt could be thrown off his land and forced to serve in the army in wars of extermination against the last Indigenous rebellions; in which republican legality resided in a dictator who was fraudulently reelected. . . . In such a society, who were the outlaws? Or better yet, in such a society, why should bourgeois banditry be considered kinder and more socially acceptable than the banditry of the rural poor?

In 1910, the Terrazas family and their partners in Chihuahua owned 1.5 million cattle, horses, sheep, and goats, while 95.5 percent of Chihuahua’s inhabitants had no property at all. Reviewing the Porfirian state’s catalog of banditry recorded by Carleton Beals, one comes to the conclusion that there were two contending classes at work: bourgeois bandits and poor bandits.

By 1910, Pancho Villa—this “tall and vigorous type, usually dressed like a cowboy”—was, to put it simply, a survivor, a poor and not-too-fortunate bandit.