four

from siberia to las quince letras

A stocky, muscular character, dressed in a three-piece suit and a Stetson hat, addressed a gathering of progressive young ladies, and therefore antirreeleccionistas, in June 1910,

They are trampling on the constitutional pact, jailing independent writers, confiscating newspapers, gagging popular writers, and seizing arms from citizens who join political clubs. What do they think will happen? This might have worked in Russia, but in Russia, there is no constitution to protect its inhabitants, and this is why I tell you that we are worse off than they are over there. There’s no shortage of people who will tell us about the horrific Siberian prisons, forgetting that we have Valle Nacional, San Juan de Ulúa, and Tres Marías, which are just as horrific prisons that the jailers of the autocrat of all the Russians could not help but envy.

The character who described the dark situation through which the Mexican Republic was passing was José Abraham Pablo Ladislao González Casavantes. He was the spokesman, the strongman, of Maderismo in Chihuahua. Maderismo was that euphoric movement of the middle classes, as timid as it was enlightened, that hoped to remove Porfirio Díaz, the nearly eternal dictator, from power.

Abraham González was the founder and president of the Club Antirreeleccionista Benito Juárez de Chihuahua, created in July 1909. He was Francisco Madero’s man. And Madero was an hacendado, son of hacendados, a spiritualist, educated by Jesuits, who studied agronomy in the United States, and business in Paris; he was thirty-seven years old, and he intended to break the dictatorship’s spine with a simple slogan, “Effective suffrage, no reelection.” Translated into the language of the day, this meant “no electoral fraud and that Díaz leave for good.” The slogan rallied an important part of Mexico’s social and political dissidents who had previously been won over to Magonismo—inspired by two anarchist brothers working within the Mexican Liberal Party—which, since the turn of the century, had confronted the dictator militarily. A gentler dissidence, characterized by a combination of praise for the dictator and complaints about his perpetuity in office. His hindrance of “modernity,” abuses carried out by “his” men was all neatly laid out in Madero’s 1908 bestseller, La Sucesión Presidencial de 1910.

Madero arrived in Chihuahua in January 1910 in the midst of his election campaign. There is a version recounting this trip, undoubtedly false, in which Madero and Villa first met on that occasion. Abraham is supposed to have introduced Villa to Madero in the Palacio hotel. If that happened, no one else saw it, not even the storytellers. It would have been very dangerous for Madero, in full campaign mode, to be seen in public with a notorious bandit.

Events now transpired in rapid-fire, beginning in April with the approval of the Madero-Vázquez Gómez ticket standing for the Partido Antirreeleccionista, followed by the elections in June. Madero was jailed, accused of subversion and machinations that, with the aid of pervasive fraud, once again handed the victory to Porfirio Díaz. In Chihuahua, Díaz won 351 votes to 35 votes (based on a system of indirect electors), but they didn’t count Madero’s votes and there were endless irregularities.

Madero was released from prison, went into exile, and launched his Plan de San Luis from Antonio, Texas. The Plan was dated October 5, the last day that Madero spent in San Luis, but it was promulgated later. “I have designated this coming Sunday, November 20 from 6 p.m. (until the given time) for all populations of the Republic to rise up in arms.” The soft opposition was hardening up. The dictatorship could only be overthrown by force of arms. The electoral network transfigured itself. Abraham González, who would receive a commission as a colonel sent by Madero who was then in the United States, had spent considerable time after the electoral fraud searching for men ready to take up arms and chose Manuel Salido to serve as the military chief for Chihuahua. Salido set about searching for military cadres. At what moment, and in what context, did he first lay eyes on Pancho Villa? It was not an easy decision to link a bandit to a political movement, especially one that was continuously discredited by the dictatorship’s media bombardment.

The story goes that Abraham considered Villa “important, yet dangerous.” The danger was clear enough, but what was important about Villa? Villa had never been a man of great deeds or a leader of large groups. He was a very good shooter, he knew Chihuahua like no one else, and he dared to take action. What did Abraham see in him that others did not? What indicators were there that the bandit Pancho Villa would agree to become the revolutionary Villa?

First, how did the two meet? There are many versions. Supposedly they knew each other during the time when Abraham was a cattle dealer and Villa a cattle thief. Most likely, they had conducted some business together.

According to testimony from Rayo Sánchez Álvarez, Villa had been introduced to Abraham by Victoriano Ávila, according to others, a certain Colonel Lomelín had contacted him. In the version told by Abraham, as related by Silvestre Terrazas, Abraham set up an appointment with him. Medina claimed that Pancho found out that Abraham was setting up meetings and went to see him. Puente said that Villa was the one who set up the meeting with Abraham. Seeing as this meeting is the fulcrum of the whole story, it’s curious that in all the autobiographies he wrote, Villa passes over this detail without giving it the least importance.

Silvestre Terrazas affirmed that Abraham González had attempted to meet with Villa several times but that he had declined. Why did Villa finally change his mind and agree to meet?

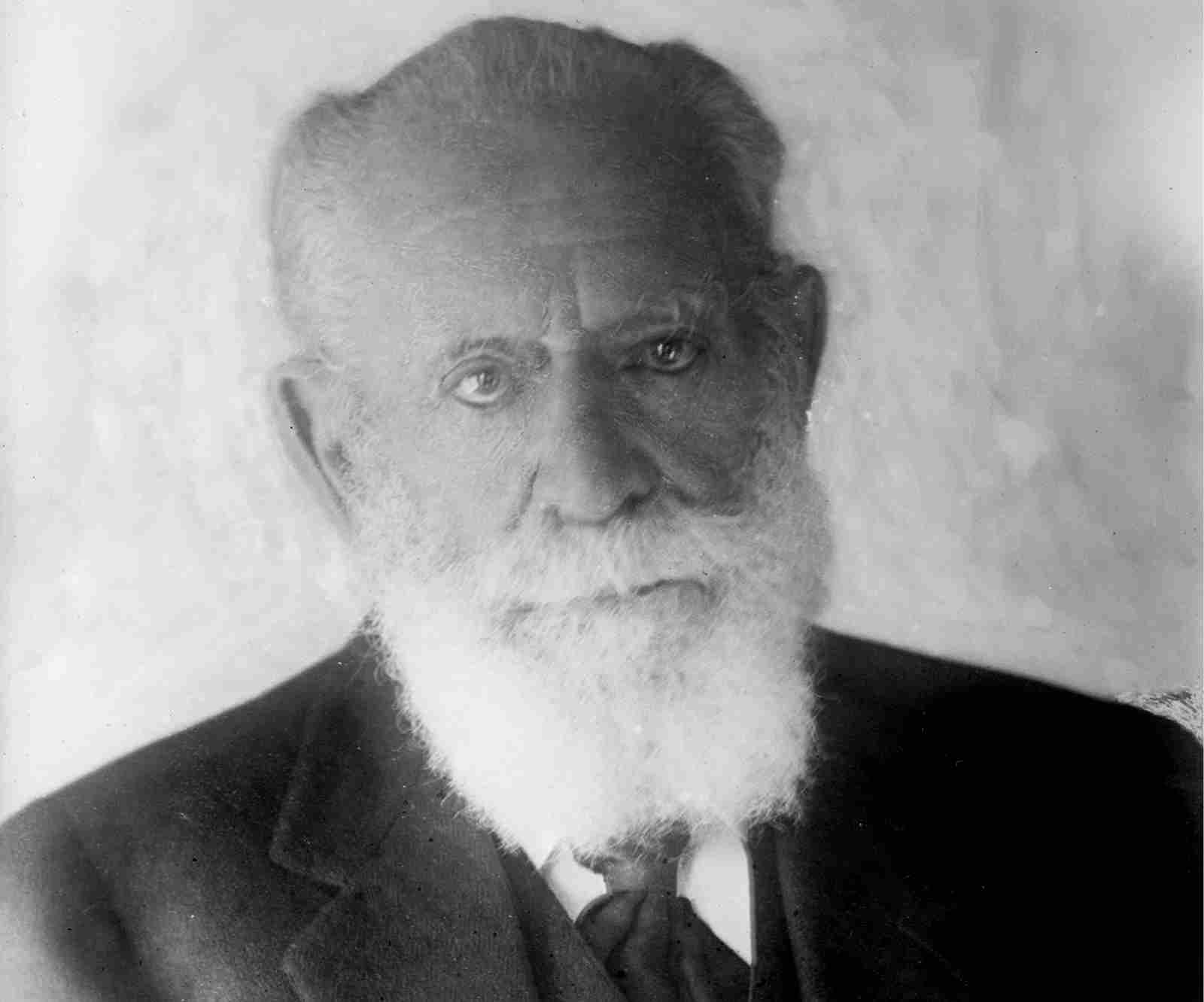

Abraham held the interview with Villa when he was forty-six-years-old. He had an unfinished teaching degree from Mexico City and a course in business from Indiana under his belt, and he spoke fluent English. In 1887, he returned to Chihuahua, where he held a multitude of jobs: bank teller, streetcar administrator, posts in the mining business, a cattle agent for some Americans. Nothing much about him stood out and he never adopted very radical language, although he was a proponent, curiously, of women’s suffrage. Fabela described him as “Tall, robust, a little bulky around the belt, brown but not dark complexion, with a bushy, graying mustache.” Puente completed the picture, “Clear, brown eyes with small flashes of green, he moved fluently and wore a contradictory expression, which appeared to be the cause of his constant walking in circles.” He was single, “the Revolution was his girlfriend.”

How the meeting was hatched remains frankly uncertain along with its date. The only precise details we have come to us from an author generally not known for his exactitude, Antonio Castellanos declared that it took place during “a night in August.” (Various other sources place the meeting in October, which seems implausible given the events that will be narrated later on.)

The meeting’s location is also the object of discrepancies. Some said it was held in Villa’s house, number 500 on Décima Street. Villa himself recalled it was held in the offices of Chihuahua’s Club Antirreeleccionista (at 259 Tercera Street) “at nine o’clock at night in a room that contained nothing besides a table with some paper and a few chairs.”

Terrazas offered a description of their first meeting: “Suspicious of others, Villa arrived at the meeting at dusk accompanied by one of his most trusted men, the one-eyed Domínguez, but Don Abraham was nowhere to be seen. They waited for him in the great hall on a long bench made from stone and wood, covering their faces with large sarapes and Huichol hats [. . .]. A short time later, the regional antirreeleccionista chief arrived and, guessing the identity of the two shapes wrapped in sarapes, entered calmly and directed a collective greeting to the visitors.” Villa finished the story, “The room was dark, and we kept our hands on our guns.” Suspicion was not such a bad quality for a man who had survived for so many years because of it and, more so because, there were several warrants out for his arrest at the time. Abraham would later recall that he took out his keys and a candle to enter his office and that the two removed their sarapes and followed him inside. He set them at ease, proposed that they join a revolution that had not yet been announced publicly and then read them bits of the Plan de San Luis.

What took place in that room? Were Abraham’s arguments so compelling that they won over Villa? Had Villa been looking for something during these last years that he finally found? A cause that could justify and give meaning to life on the edge, where gun and danger walked hand in hand? A direction for his actions? Villa had no political training. Some sources claim that he had previously read the Plan de San Luis in a cave in which he was hiding, others maintain that he had encountered Chihuahuan Magonismo. As far as we know, neither is true.

However, this wouldn’t be the last time Villa would be dazzled by some character’s speech as long as it helped explain the ideas he already held in his head, even if in a chaotic form, and as long as the speaker paired his fervor with sincerity.

The fact is that, in what Vargas calls “something like the fable of St. Francis of Assisi and the wolf”—even if we don’t lend much credibility to the idea that Villa adopted Abraham’s ideas after just one conversation, leaving aside Villa and Abraham’s future testimony attesting to this—the encounter produced a radical change in our story. Villa explained it in the simplest terms, Abraham González seemed “sharp” and won him over.

And so, from one day to the next, Villa became a revolutionary without a revolution, a retired bandit, outside the law but not without a sense of justice, an avenger of grievances. Was the transition very difficult?

While waiting for Abraham’s call, Villa took part in an action that would signify his definitive break with his double, semi-clandestine life in the city of Chihuahua.

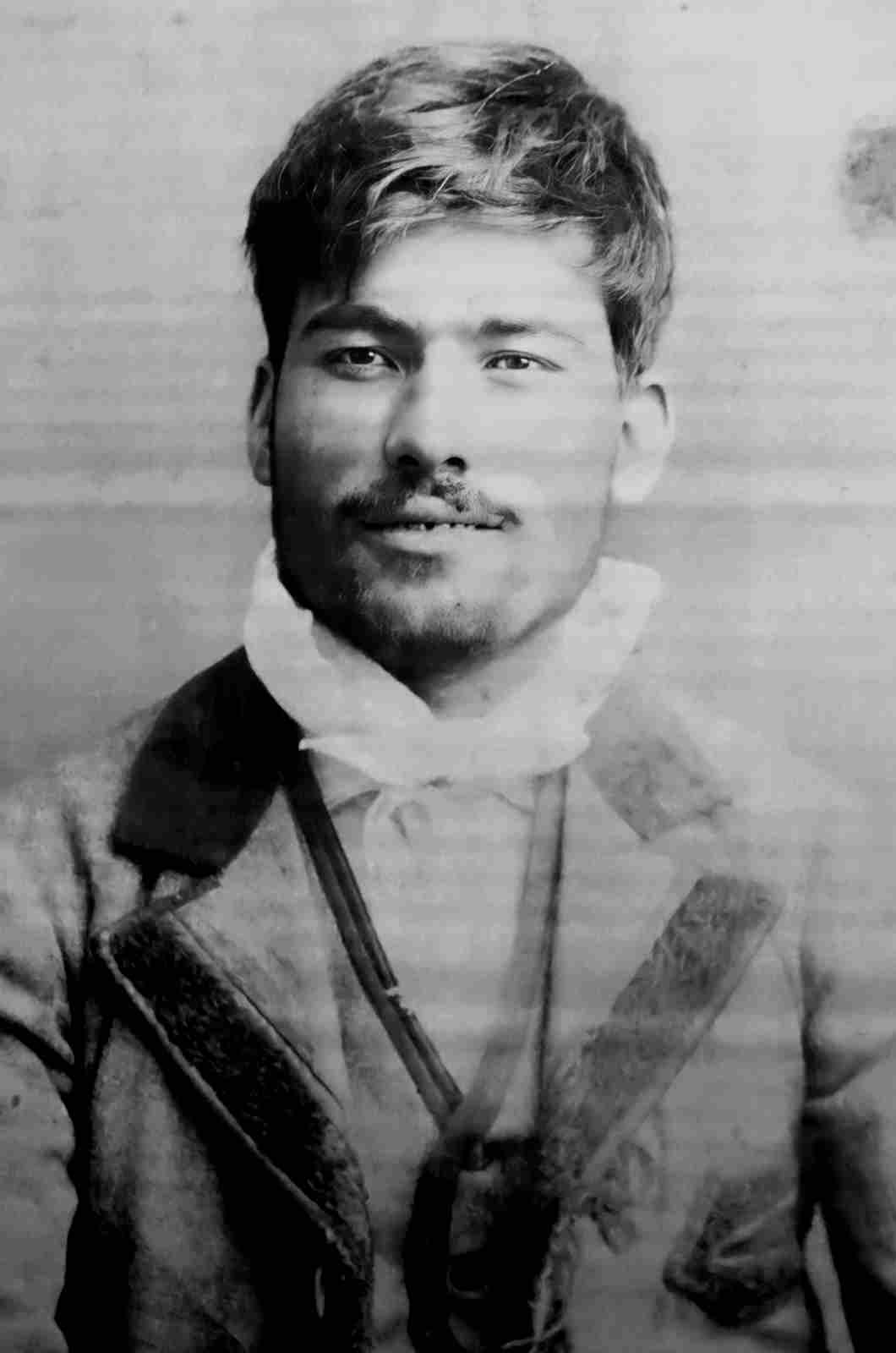

Claro Reza was twenty-two years old. He was tall, thin, with a robust complexion, a nose like a hawk, brown eyes, bushy black eyebrows, and a mustache. He was likable, violent, and loved horses. He was married and had three children. He was politically restless and linked to Antirreeleccionismo. But he also had a secret life: Reza was a member of the police reserve. The press would inadvertently give away his secret sometime later, “this officer, an ex-prisoner, was commissioned by Police Headquarters to capture and charge several cattle rustlers.”

Villa stated, “Claro and I sold stolen cattle to Enrique Creel, who one day refused to pay us the agreed-upon price, then the authorities started coming after me for stealing cattle.” Reza went to jail for robbing some burros (or twenty-two head of cattle) and negotiated his release with Juan Creel, telling him that if he were set free and given a job with the Rurales, he would hand over Villa. “The Creels bribed my compadre Claro to betray me.” Reza was jailed with Pablo López and another prisoner and was then sentenced to four years and eight months, but was released some weeks later, promising to deliver his accomplices to the mayor, Santos Díaz, who also happened to be the chief of the Rurales.

One day when Villa was going to a meeting with Abraham González, he, Soto, and Sánchez were surrounded by twenty-five Rurales under the command of Claro Reza. At four o’clock in the morning, when the trapped men had decided to make a break for it by opening fire, the Rurales withdrew. Did they want to avoid a shoot-out? Or was Claro planning to hand over Villa, but then had second thoughts about his loyalties?

It has been suggested, although without much in the way of evidence, that Reza was in on the secret about the upcoming revolt (Madero’s call had not yet been issued) and, despite having been sworn to secrecy, he was going around spreading the news.

Villa, on one of his trips into Chihuahua, came across Claro Reza who was surrounded by some people at the corner of 22nd and Zarco Street, outside the doors of butcher shop number 14 across from a saloon named Las Quince Letras (Fifteen Letters). And what were these fifteen letters? Hijodelachingada (Sonovabitch) has sixteen letters, chingatumadre (fuckyourmother) and Viva Chihuahua each have thirteen.

The meeting took place on September 8. It was a “Thursday at ten o’clock in the morning when three unknown men arrived at this location, mounted on chestnut, black, roan, and gray horses, respectively.” (A curious journalistic chronicle that places three horsemen on four horses.)

Villa approached him and said, “Claro, I have a matter I have to settle with you,” Claro responded, “Sure,” and went off towards a “canal” where Villa followed. Without warning, Villa discharged his pistol. Two bullets hit Reza, “two .44-caliber bullets and the copper casing of an exploding bullet,” according to the autopsy, each of which produced a fatal wound. If he had reached for his gun, he didn’t have time to use it. One of Villa’s compañeros dismounted, took Villa by the arm, and led him away.

With no one standing in their way, Villa and his two companions calmly and defiantly walked their horses until they reached the guard shack. A corrido song sung much later adds that they stopped for ice cream along the way. It was probably true.

Eight mounted police took off after them and “sent orders telephonically to authorities in neighboring towns to proceed to organize a posse.” Fifty men joined the pursuit soon after the shoot-out. Villa had been clearly identified.

Despite being hunted down and his name being on everyone’s lips in Chihuahua, Villa continued to come and go from the city. He held nine meetings with Abraham as preparations intensified since Madero’s October 5 call for insurrection had been written up. Ramón Puente said that one time when he had gone to visit a sick relative, he saw Villa at his house on Décima Street with a stockpile of arms and horses. It wouldn’t be the only time. Jesús Trinidad Reyes remembered attending a nighttime party in which Villa—who was already being pursued by that time—befriended a butcher named José Alcalá. He recalled Villa being very entertaining, giving out coins to the children. However, he had someone standing guard outside while he took part in the festivities. Still, other witnesses recounted that a boy, about ten years old, served as a lookout in the doorway. “Here comes the doctor,” was the signal for Villa to take off at a gallop.