eight

“these dandies have made a fool of you”

After the Federales surrendered, a bloody episode followed that put the liberals on edge and spoke to Villa’s character. A group of soldiers handed over to Pancho a civilian they had detained, the old owner of a hardware store. When Villa attempted to find out why he had been detained, the man told him that “he had killed more Maderistas than Federales.” Over the course of the three-day battle, he had set himself up as a sniper from the roof of his store with a .22 caliber rifle (more anti-clerical witnesses would claim he fired from the roof of a church). Right then and there, Villa took out his pistol and shot him in the head.

Villa then dedicated himself to resolving the terrible chaos left over after the fighting. He sent a group of ten men to dig a mass grave in the cemetery and organized a brigade to collect the bodies of the dead. He went to José Muñiz’s bakery and ordered him to put all his bakers to work. At five o’clock in the morning, he handed out ten sacks of bread to the imprisoned federal troops and then to his men; those who hadn’t eaten were called to the “mess hall.”

One observer recalled seeing the day after the battle “arms over each other’s shoulders, relaxed and conversing cordially.” Abraham had received news that Villa’s troops had been looting and he was complaining to him forcefully. Villa said he would make them stop. Abraham replied, “It dishonors us.” Villa responded by saying he agreed but that his troops were without food, medicine, and soap and that their horses needed pasture, but that he would get his people in line.

This same afternoon the famous Col. Tamborell’s funeral was held. Madero, who wanted to remain on good terms with the defeated army, ordered his brother Raúl to represent him at the funeral, at the head of a guard unit in the name of the Maderistas. Neither Villa nor Orozco were present. Their absence did not signal a lack of generosity on their part as this same day Villa visited Gen. Navarro in jail and told him that “all feelings of rancor had disappeared,” and “all that remained was admiration.” The two embraced and Villa invited him, and nine of his imprisoned officers, to dine at the Ziegler house in El Paso as long as they swore to return to the jail afterwards. Villa never lacked style, but it was one thing to display generosity and another to forgive a man who said Villa’s troops didn’t have any balls.

Meanwhile, the press published mystical suppositions. Names like Pancho I. Madero, Francisco Villa, Pascual Orozco, José Garibaldi, and José Luz Blanco all contained thirteen letters, even if it was necessary to change Pancho for Madero and Francisco for Villa, cut out the “de” from De la Luz, and convert Giuseppe into José as one Mexico City daily newspaper endeavored. Madero, given his spiritualist vocation, would have enjoyed all this.

The day was taken up by small tasks. El Paso served as the medical rearguard for the triumphant revolutionaries. Previously they had attended to their wounded from Casas Grandes there and now those injured in the three days of fighting in Ciudad Juárez had their turn. Villa visited one of the improvised hospitals with his compadre José Ávila where he was photographed wearing a grim expression, surrounded by nurses.

On May 12, Roque Estrada was at the bar at the Sheldon Hotel in El Paso, when Pascual Orozco arrived and the two shared a beer. Orozco was furious with Madero. His secretary, José Córdoba, had gone to see Madero with a request to deliver food to his troops and Madero replied that they should “deal with it themselves.” The conversation ended when Orozco uttered the enigmatic phrase, “Madero’s too round for an egg.”

Whether or not he was round for an egg, that morning Madero announced his cabinet and introduced a new element of discord among his followers by naming Venustiano Carranza Minister of War. The politician from Coahuila had had little to do with the war. In fact, during the first part of the campaign, he had not been seen in Chihuahua, and during the combat in Ciudad Juárez, he had not stepped foot in Mexican territory, remaining at the Sheldon Hotel like just another civilian. He was not the best choice among a camp filled with warriors.

Pascual Orozco continued making the rounds, carrying on angry discussions about Madero. In mid-morning he visited Toribio Esquivel—who curiously had represented the enemy during peace talks—in the El Paso Hotel. Orozco arrived with a guard who he ordered to return thirty minutes later. Esquivel reported that Orozco complained that his troops were going hungry and that many people with “poor judgment” were close to Madero. They say that Díaz’s envoys, Braniff, and Toribio Esquivel observed the discontent and tried to cultivate a relationship with Orozco. Madero himself would believe this later on.

Villa added that during a “mysterious nighttime meeting,” Orozco proposed executing Navarro, who had been responsible for the firing squad at Cerro Prieto. Although Villa had made peace with the general the previous day, the Cerro Prieto wound must have been raw as Orozco had lost an uncle in the fighting and Villa had lost some of his best friends and compadres. There was clearly a desire among the troops to try Navarro in a military court. Albino Frías sent Madero a telegraph on the same day demanding that Navarro—whose safety he would guarantee—be sent to appear before the widows and orphans of the men he had executed.

But it’s unlikely that either Navarro’s fate or Venustiano Carranza’s appointment as Minister of War were the main source of tension, Villa wouldn’t have cared much about the post (although Orozco might have been hoping for it). The real problem was the lack of food for the troops and the general disdain for the popular army displayed by Madero and his advisors. At any rate, Villa and Orozco scheduled a meeting at the revolutionary government’s headquarters for the following morning.

At sunrise on May 12, Maj. José Orozco and Capt. Olea’s troops formed ranks in front of the Customs House. Orozco and his general staff arrived soon after with Villa and fifty of his men close behind, who lined up double file on the opposite sidewalk.

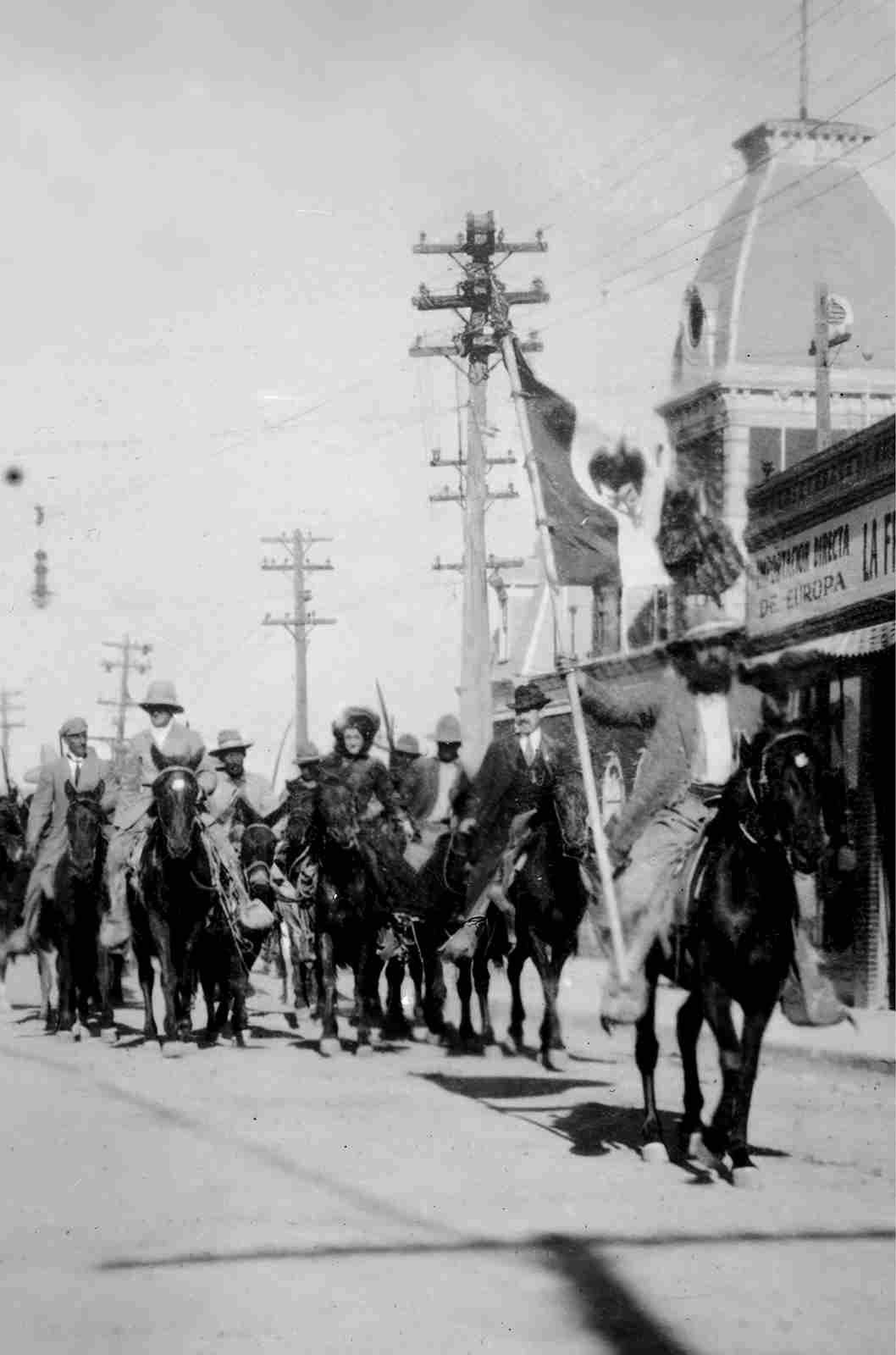

There is a pair of photos taken by H.J. Gutiérrez showing Villa and Orozco’s troops in front of the main garrison. In one of them, they appear relaxed, some are sitting on the edge of the sidewalk, others leaning on their rifles. There are about two hundred troops and there are no signs of tension. In the second one (published soon after it was taken), curiosity seems more apparent than worry as a crowd of armed men gather around the Customs House, some of them attempting to maintain their formation, but children and onlookers are mixed in.

At around 10 a.m., Madero appeared, accompanied by Abraham González and his guard, led by Máximo Castillo. The presence of armed troops seemed to unnerve him, but Madero entered the building, followed by Orozco and Villa.

What happened next drained inkwells, wore out typewriter ribbons, and exhausted printer cartridges over the next ninety years. The story was told and retold by its protagonists, by friends of the participants, and historians, it was used as ammunition in political struggles and denunciations; proof of betrayal and lack of loyalty by some, and the innocence of others. Particularly in the five or six subsequent years, it would be used and used again. Rummaging through some twenty competing versions, the narrator has tried, with some difficulty, to set out the proper order of events.

The following day, Madero tried to smooth over the events in order to counteract an alarmist deluge in the press that could only weaken him during negotiations with the dictator. He claimed that Orozco “was complaining that his troops did not have sufficient food and that he wanted to place the blame on people I had designated to supply the army, but the truth is that we have plenty of provisions, thus, the real fault lies with the person responsible for supplying his troops who has not fulfilled his duty. Moreover, he told me that he is not pleased with the people I have named as advisors (referring to Venustiano Carranza), but I told him that he was not in charge of telling me who to appoint.”

Other sources indicated that, besides complaining that “he was not providing food for the people,” Orozco and Villa reported that the troops were demanding that Gen. Navarro be tried by a military court. An exchange of words was soon followed by pushing and shoving and Abraham González fell to the floor. The journalist Gonzalo Rivero asserted that whatever happened inside the building lasted “no more than ten minutes.”

At a certain point, Orozco tried to take Madero by the arm, but he slipped away and headed for the door. Villa, pistol in his hand, stepped in front of Madero who yelled, “Really, Pancho? You’re against me too!”

Castillo, who was standing outside, continued, “I saw Villa leading Señor Madero with an outstretched arm and that Señor Madero was resisting.” Villa was trying to lead Madero out, telling him, “Walk, walk.” A couple of guards separated the two. Madero shouted, “Shoot Villa!”

Madero made his way towards an automobile that was parked along the sidewalk. In the middle of all the drama, Orozco emerged from the building with a pistol in his hand. There were already a lot of guns out. Roque González Garza took out his gun and threatened Orozco. Villa’s appearance prevented a shoot-out. Orozco followed Madero and said, “Give yourself up, Señor Madero.” Madero got away from Orozco and went after Villa who was standing in the doorway. The two quarreled.

Meanwhile, Castillo and Orozco were confronting each other face-to-face, guns in hand. Madero climbed into the car, but Orozco stood on the sideboard without knowing what to do. Castillo’s guards pushed him down. Raúl Madero challenged Orozco, gun in hand, and Abraham González grabbed him, immobilizing him. All of this happened in a matter of seconds, in a very few seconds, amid yelling, threats, and guns out, all in the confounding presence of hundreds of armed men.

Madero mounted the roof of the parked car and addressed the ranks of assembled soldiers, telling them that Orozco and Villa wanted to depose him. US journalist Timothy Turner remembered that the troops in the street yelled death to Navarro and that Madero replied he would not permit his prisoner to be lynched. Then he asked the soldiers, “Who do you obey? Me or Orozco?” The shouted results were mixed with the same number answering Madero and Orozco, while some said “both.” Orozco, standing beside the car, insisted, “Give yourself up, Madero.” In a somewhat absurd discussion, Madero told Orozco not to use his pistol. Orozco insisted that he would use it if he had to. Madero then opened his arms towards Orozco to embrace him. This whole act, with mutual insults shouted back and forth, with others joining in, was reproduced in ten different small parallel scenes that, like on a main stage, ended in an embrace to bring the story to a close. Orozco, pissed off, complained to Madero, “You are a useless man, worthless, you are not even able to feed the people . . . How are you going to be president? You’re a charlatan.”

Madero didn’t answer, instead turning to the troops to say, “Everything has been arranged, there will be food and clothing available shortly.” And he insisted that Orozco shake his hand. Orozco’s own officers, Olea and José Orozco, urged Pascual to extend his hand to the president. Madero later said, “Orozco and I shook hands, and everything was forgotten; of course, if it was clear that he had just committed a mistake, he had also served the nation in important ways.” In his own version, Villa was taken by surprise; when he got his bearings, he ordered the men standing in the street in formation to return to their barracks. A few moments later, Madero signed a check himself on the spot for $40,000 pesos to buy food in El Paso for the troops.

Villista sources claim that once they were back inside the building, Villa demanded that Madero order that he be shot because he didn’t deserve to live after his outburst.

After the confrontation, Madero decided to protect Gen. Navarro:

Because I feared that some badly-advised soldiers might commit an outrage against Gen. Navarro, I immediately took him to my residence; however, since I could not be constantly at his side, and given what had just occurred, I personally escorted him to the river’s edge so that he could enter American territory, where he would remain my prisoner of war, based on his word of honor [. . .]. To his credit, I must state that Orozco himself proposed to me from the beginning that we proceed in this manner, and even Villa, when I declared my intention to spare Navarro’s life, told me with all humility that I was doing the right thing.

Navarro affirmed that “I owe my life to Madero [. . .]. He drove me in an automobile to the river crossing, facing Washington Park.” From there, the general crossed over into the United States on horseback.

Madero issued a declaration to the press that same day clarifying what had taken place. He attributed the events to the fact that Orozco had acted out of “flattery and bad advice from persons interested in sewing disunion between us.” He continued, “Accordingly, there is no truth to the idea that I, even for an instant, have considered, or suggested, that it is necessary to dismiss any of the Advisors I appointed only a few days ago from their posts, nor that any of them have fled to El Paso.” He closed with a show of confidence for the peanut gallery, although what he said next must not have eased tensions, “This episode, although unfortunate, leads me to insist on one more item, that is, to be certain that I can count on my soldiers and commanders in all circumstances, although they may lose their way for a moment, they must never dare to disobey my orders.”

The reaction of the politicians accompanying Madero was immediate. “Alfonso” wrote to Madero (addressing him as “my dear brother”) asserting that Esquivel and Braniff were responsible for the conspiracies “with their conversations with the commanders in which they discussed the political appointments.” He suggested that Madero send his officers on “expeditions” and that he create a regiment with Villa (“as he doesn’t question your orders”) invested with “Supreme Powers” subordinate to the president (Madero), as Benito Juárez had done in his time.

Madero, in fact, blamed the mutiny on Dٕíaz’s envoys Braniff and Esquivel. When Madero’s secretary Sánchez Azcona told Esquivel in El Paso that he had best not return to Juárez, Esquivel assured him that it was not true that he had paid off Orozco, only admitting that he had talked to him to smooth over his rejection of their common desire for peace. Braniff would write to Madero along the same lines. However, the president broke off relations with them, convinced, as Roque González Garza wrote, that “Don Porfirio’s commissioners were working overtime to undermine him.”

The following day, May 13, a tense atmosphere hung over the Maderista camp in the wake of the attempted insubordination. Everyone disagreed with everyone. Only Madero had recovered his equanimity. The Boer Viljoen wrote a note to Madero in which, besides warning him that “the federal emissaries are trying to turn your officers against you,” he suggested cutting Pancho Villa loose: “It would be wise to find some excuse to dispatch Villa to some other place or to get him out of Juárez, and to free yourself of Villa at the soonest possible moment [. . .]. I would like to suggest that you call together your officers, including Orozco, Blanco, Villa, Garibaldi, and others who have influence over the men and formally discuss with them appointments to your cabinet as well as military command appointments in Juárez, thus undercutting their accusation that they are not being recognized. This is necessary because they are in Juárez, in the plaza they have captured. It would be good to name Orozco Minister of War. I think it would be good to find some excuse to dispatch Señor Villa to some other place to send him away from Juárez and to free yourself from this man the first chance you get; he will be a detriment to you for as long as Villa has power.”

That day, only twenty-four hours after the incident, Roque González Garza, another figure working towards détente among the Maderistas, accompanied Villa to El Paso and listened to him express his anger towards the president. But Sánchez Azcona, Madero’s secretary, saw things differently, believing that the confrontation had left two deep marks on Villa, namely, “unlimited admiration and a profound affection towards the movement’s originator.” The truth, as events will show, was a mixture of these two realities. Villa, however, continued to nurse a certain resentment towards Orozco, feeling that Orozco had drawn him into the confrontation with Madero. The journalist Guillermo Martínez, who was present at the time, registered Col. Villa’s irritation, capturing in a single word Villa’s distrust of Orozco. Villa would only say that Orozco “is very quiet,” and nothing more.

Two days later, Madero wrote a letter to Pascual Orozco that would be made public—and had probably been written so that it could be made so—saying, “The popular imagination, as well as our adversaries, have made more of this than it deserves [. . .]. If it’s true that we had a relatively heated argument, we were a long way from entertaining the idea of being divided [. . .]. I have never doubted your loyalty to my government.” Orozco replied, “Our union is indestructible.” The incident had been resolved.

Madero, after a brief interlude, could get back to leading the rebellion. He had not made any military decisions to advance towards the state capital, surmising that the fall of Ciudad Juárez would be sufficient to overthrow the dictator. Juárez was not particularly consequential militarily, however, twenty-six out of the thirty-one states comprising Mexico were home to armed movements, including both guerrilla and more organized forces, of greater or lesser intensity. The railway lines were cut off north of Saltillo, making it impossible to reach the Federal District from Guadalajara. The seizure of La Piedad by the rebels impeded access to Manzanillo. The tracks to Chihuahua were blockaded from Aguascalientes on, the railway to Laredo was cut to the north of San Luis. Pachuca and Cuernavaca had been taken by insurrectionary troops. This same was true of Iguala, Cuautla, Colima, Mazatlán, and Tepic. It was true that the size of the rebel forces was still not significant and that the Federales had mobilized only 14,000 out of their 30,000 soldiers. And it was true that the revolutionaries were rebel-thieves, riffraff, and cattle rustlers as the Porfirista press scoffed, and that they were badly armed, and had barely any military leadership. But the dictatorship was coming apart at the seams.

On May 17, Madero announced a five-day cessation of hostilities upon learning of Porfirio Díaz’s resignation. The New York Times reported that Col. Villa did not appear to be “happy about anything.” That same day at 3:30 p.m., Villa crossed the international bridge and entered El Paso. He was armed and he was furious. Garibaldi was in the Shelton Hotel lobby when he saw Villa arguing with the hotel manager. Villa lost control and asked Garibaldi for the names of the gringos who had accused him of being a coward. Before Garibaldi could respond, the El Paso sheriff and two other men detained Villa and disarmed him, depositing him unceremoniously on the other side of the border. The Secret Service prohibited Villa from entering El Paso while armed from then on.

That night, a banquet was held at the Ciudad Juárez Customs House to celebrate the victory. Villa recalled many years later, probably spicing up the dialogue based on future events:

I was seated at the table feeling out of place and the truth is I didn’t like the food. The time came for speeches and the whole gaggle of politicians talked about how great everything was. The only ones who remained quiet were Orozco and me. When he noticed this, Madero stood up from his seat and looked directly at me, and said the following words:

“What do you think, Pancho? The war is already over. You don’t like it?”

I refused to say a word, but Gustavo, who was sitting near me, said to me under his breath, “Come on, chief, say something.”

At long last, I decided to stand up and I remember exactly what I said to Señor Madero, nothing more and nothing less. “You, Señor, have already ruined the Revolution.”

“I see, Pancho,” replied Madero. “Why?”

“It’s simple: this bunch of dandies have made a fool of you, and this will eventually cost us our necks, yours included.”

“Fine, Pancho, tell me, in your thinking, what should be done?” asked Madero.

“That you authorize me to hang this roomful of politicians and let the Revolution continue.”

Well, seeing the astonishment on the faces of those elegant followers, Madero was startled and replied, “You’re a barbarian, Pancho! Sit down. Sit down.”

I turned to look at Gustavo Madero who clenched his fist in reply to what I had said.

But not everything was handled so gently or light-heartedly, so agreeably or so amicably. Madero apparently wrote a letter to his irregulars in Chihuahua stating, “Col. Francisco Villa is relieved of his command and there is no good reason to reinstate him because he is a dangerous man.” It is debatable whether or not this document exists, the revolutionary leader’s attitude appeared to lend credibility to it. The word dangerous was often associated with Villa’s name in Madero’s circle.

The following day, Raúl Madero visited Villa and asked him to meet with his brother Francisco. Pancho met with Madero at the Customs House. There, the provisional president of the Revolution proposed (or Villa himself offered) that he be discharged from the rebel army. Either way, they left the meeting with an agreement that Villa would leave. Madero suggested that his brother Raúl take command of Villa’s troops and offered him $25,000 pesos. Villa did not accept the money. Years later he would claim, “I did not join the cause for money but only to win protections for the poor that had been denied to them, that is to say, I would go back to work to make my living if he was offering me those protections because the Revolution had triumphed.” Finally, after Madero insisted, Villa accepted $11,500 silver pesos (Villa remembered only accepting $10,000 pesos), which was duly recorded in two documents establishing an accord with the provisional government. The first was signed by Madero, stating that the money corresponded to “expenses paid by Villa in support of the Revolution, as well as his salary and compensation for services rendered to the cause,” while the second comprised a note from the Secretary of the Interior confirming that the funds issued to Villa “be considered funds paid upon his discharge” from the rebel army. Curiously, there was a condition attached, “This sum will be paid as soon as Col. Francisco Villa and his family are settled in Los Angeles, California.” Thus, Villa had not only agreed to relinquish his brigade but also to go into exile. This part of the agreement was never spoken of again. Villa never mentioned it and Madero seems to have forgotten. Villa formally transferred command of his brigade to Raúl Madero and departed with his $11,500 pesos, using it to purchase 1,500 tons of corn for the widows of the men who died at San Andrés.

There is a photograph depicting Villa after the fighting has ended. We see an elegant, clean-shaven Villa, mounted on a white horse, looking almost like a caricature. Villa had dropped his surly expression from earlier days and looked happy.

On May 21, the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez was signed. Porfirio Díaz and Vice President Corral resigned their posts, appointing an obscure figure named Francisco León de la Barra ( Díaz’s Minister of Foreign Relations), to act as the provisional president in charge of convening new elections. The revolutionary troops were to be discharged.

Yet this same day, a group of Maderista soldiers from Pancho Villa’s brigade wrote a letter to Madero in which they put forward a series of grievances and doubts: It’s not right to abandon the widows of the fallen rebels. Why aren’t we marching on Mexico City? We don’t know what to expect. Many of us don’t have the means to return home. There’s no guarantee your program will be put into practice.

There is no record of a reply.

The English historian Alan Knight tried to present an overall view of the military situation (Villa and his men’s own situation being similar) summarizing, “The overwhelming problem was that the Liberation Army constituted a military hydra, with dozens of cabecillas exercising local, personal authority in the different regions and defying coordination.” He was totally wrong. In fact, this was a popular army that could be organized if only a social reply was given to its demands. But the problem was not with the revolutionary army’s supposed disorganization, it was the other way around. In fact, the negotiations had left the armaments, structure, command, and all the reactionary, authoritarian, and oligarchic tendencies of the Porfirian army intact. And this would bring Maderismo to grief, costing Pancho Madero himself, the movement’s guiding figure, his life.