nineteen

a hard bone to crack

The trains Villa captured opened up enormous possibilities, but they couldn’t transport the 4,500 men he was moving towards Chihuahua, only the commanders and the infantry traveled in the cars. Ontiveros, from the Ortega brigade, recalled: “The cavalry crossed the immense desert that extended from Torreón to Jiménez in six days, enduring extraordinary challenges. Walking across that arid and dry terrain where there was no water for their horses; many of them could not bear such deprivation and were left in the desert. The people suffered terribly as well, having no provisions and nowhere to get them along the way, there were regiments that slaughtered mules and cows for their meat.”

Around October 12 or 13 in Jiménez, Villa began to design the new offensive. Rumors ran through the camp that an attempt on his life was being prepared, who knows from what quarters, but it was thought to arise from among his own compañeros. Villa put a stop to the murmurings: “Don’t raise a scandal or make accusations. I don’t want to hear rumors, I want evidence.”

Villa sent his brother Hipólito and Carlitos Jáuregui to the Presidio region across the border from Ojinaga with the first $300,000 pesos he expropriated from the Laguna-area oligarchs to buy munitions. One witness would recall many years later that “Candelaria and Presidio were Villista towns” and that “at least thirty people from Presidio sold guns to Hipólito.”

On October 16, Villa returned to Torreón by train at top speed with only part of his guard to resolve what might become two serious problems in his rearguard. Rodolfo Fierro had gotten into a confrontation in a gambling establishment with one of the officers from Aguirre Benavides’s brigade, García de la Cadena. Stripped of his pistol, Fierro had either killed him in a duel, or had murdered his comrade in arms in cold blood; it was never very clear. In an episode reminiscent of the Tartarus, the Greek abyss where the wicked were punished, Fierro took out a knife from his boot and flung it at Cadena from ten meters away, killing him. The act put the Torreón garrison on edge. Aguirre Benavides ordered Fierro tried by a council of war and was going to have him shot. Villa’s arrival stopped the execution, but Aguirre threatened to quit the movement and Pancho was at pains to convince him to stay.

Villa needed Fierro at the time, and this was the second reason for his trip. He urgently needed money to keep the Division of the North on its feet, most of all to purchase ammunition, and Lázaro’s financial schemes were not functioning as planned. He assigned Fierro to act as Lázaro de la Garza’s collection agent. His mere presence and sinister reputation were enough to make many of those who hesitated to hand over their portion of the forced loans pay up. Lázaro de la Garza had designed his list in an arbitrary fashion, excluding his friends and acquaintances, even those who Villa defined as “Huertistas and reactionaries.” Those handing over loans included the Germanic Bank of South America, and banks from Torreón, London, and Mexico City.

An important source of obtaining money was selling confiscated cotton. The problem lay in how to get it to the United States as there were no border crossings in rebel hands. All the same, Villa assigned trains to Lázaro to send the bales of cotton to Chihuahua. When the wagons with the cotton from Torreón finally arrived in El Paso, the hacendados tried to prevent its sale and recuperate their property.

De la Garza was becoming a key figure in the new Villista apparatus, including making financial arrangements for Laguna-region brigades, the organization of the rearguard, military affairs, and relations between the brigades. During this time, George C. Carothers, the ex-US consul in Torreón, who was then in Mexico City, contacted De la Garza and offered his services, but nothing immediately came of it.

Villa wasn’t able to spend much time in Torreón, despite the fact that his relationship with Juanita Torres bound him to the city. On October 20, he returned by train to Jiménez, being advised that the column led by Gen. Castro sent to fight him had departed from Chihuahua and that it already controlled Camargo and was on the move. However, this was not the case. The Chihuahua brigade had received orders from Gen. Mercado to fall back because Mercado did not want to entangle his forces in scattered fighting. The stuffy career military man was not without reason. However, while in the city of Chihuahua, surrounded by impeccably-dressed and elegant officers, he let himself be photographed in a pointy Prussian helmet. Among the Colorados, he was branded a coward, word spreading that Villa sent him into a panic. His inaction would cost him dearly.

Villa sought out the last of the caudillos in southern Chihuahua, Manuel Chao, whom he interviewed in Jiménez and with whom he discussed whether he would remain within the new Division of the North. The discussion got heated. Villa liked Chao, that singular, thirty-year-old “northerner” who had been born in Tuxpan, Veracruz, but moved at an early age to Chihuahua to work as a schoolteacher. Nonetheless, there was a tense moment during their discussion when it looked like they might draw their guns. In the end, Chao ended up giving into Villa’s pressure and Villa embraced him, this Maderista from the early days who hailed from Navarro, Jalisco and was “short of stature, prematurely balding, with precise features [. . .], cordial and affable,” with a scarcely bellicose physiognomy.

Thus, Villa had succeeded in unifying the Chihuahuan guerrillas. Including Hernández’s people and the 200 men with Chao (plus the growing number of volunteers) the Division must have numbered 5,500 combatants.

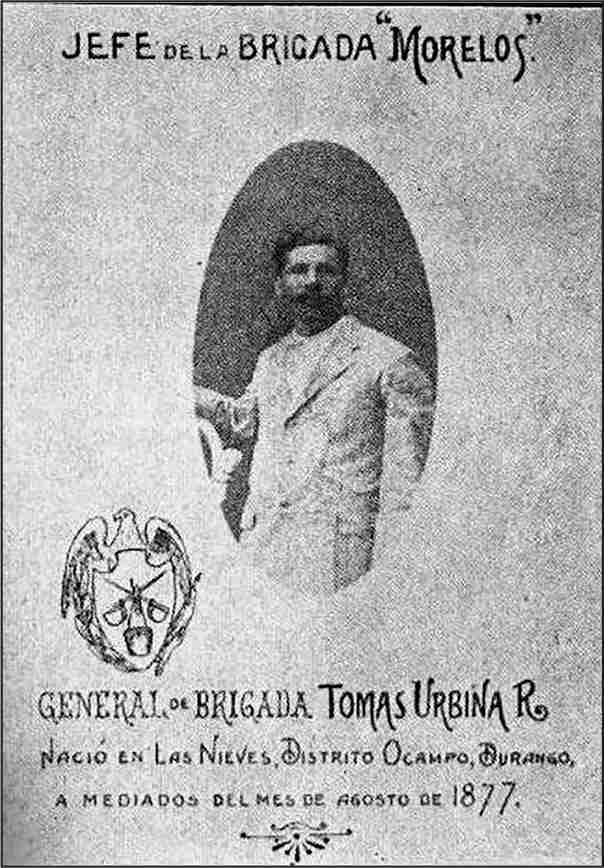

Financial difficulties and problems in the rearguard in Torreón seemed interminable. Trinidad Rodríguez reported to him that Urbina, who had remained in Torreón, was holding some $100,000 pesos from Lázaro de la Garza’s collections. Villa, in the presence of Maclovio Herrera, Martiniano Servín, Rosalío Hernández, and Fidel Ávila, said to Trinidad: “My friend, you see what’s happening, either he brings me the missing $100,000 pesos, or I get ready to send his cadaver back to Jiménez.” Then he sent his seconds in command, Martín López and Benito Artalejo, to Torreón. “This money belongs to the Revolution, and they told to me that Trinidad took the money from my compadre Urbina.”

At any rate, the rumor of his impending arrival preceded him because by the time he reached town, it was unnecessary to pressure Urbina because he had already returned the money.

On October 23, before the Federales retreated, Villa once again entered Camargo and held a meeting with his general staff in the train station. Villa proposed attacking Chihuahua. The other rebel officers believed Chihuahua would be a hard bone to crack, the garrison had more men, including the best of Orozco’s Colorados, and they had had time to fortify the city and build defenses. Villa pressed his opinion.

Meanwhile, as soon as he arrived in Camargo, Col. Benjamín Yuriar killed a soldier during a fight in a brothel, then assembled his troops and put them on a state of alert. Villa had had problems with Yuriar because he had no interest in fitting into the Division’s new structure and when Pancho sent for him with Toribio Ortega, Yuriar told them to go to hell. Villa immediately sent Benito Artalejo and his guard to detain him, they organized a summary trial, and condemned him to death for insubordination. Yuriar, ice in his veins, gave the order for his own execution.

Villa remained in Camargo between October 23 and 27 and, with Juan N. Medina’s assistance, once again reorganized the Division of the North in preparation for the clash with Mercado and Orozco in Chihuahua. They strengthened three brigades that answered directly to Villa: The González Ortega brigade led by Toribio, the Cuauhtémoc brigade led by Trinidad Rodríguez (that had been detached from Urbina’s troops), and Villa’s own brigade often led by José Rodríguez.

The financial relations with Torreón, overseen by Lázaro de la Garza, became more and more important. Over the course of two months, almost one hundred letters and telegrams were exchanged dealing with a wide variety of problems, including two absurd messages in which Villa asked the financier to use a password when speaking to foreigners, but then told him not to use it because he had lost the password. Calixto Contreras, the garrison commander, took over from Fierro’s work in pressuring the wealthy to make payments on the forced loans. No doubt, the system was working because on October 26, Villa sent a letter from Camargo to the journalist Silvestre Terrazas (who was then in Ojinaga, still controlled by the Federales) asking him to arrange the purchase from Shelton Payne in El Paso of 200 special .30-caliber rifles and half-a-million cartridges to match, along with one million Mauser 7mm cartridges, 300,000 thousand .30-30s—indicating that they had succeeded in switching out the brigades’ old Winchesters for captured Mausers—and two thousand .44-caliber and one thousand .38-caliber bullets (for their pistols). He sent him checks via Miguel Baca Ronquillo and said that he would cover the debt upon request.

All these financial maneuvers gave rise to a rumor that reached the press; namely that Villa was trying to purchase a car using silver and $1.5 million pesos that he was going to send to the United States through Ojinaga destined for a personal bank account.

At the time, Villa was dining at Rosalío Hernández’s house. Rosalío’s wife was pregnant, and they agreed Villa would become the godfather when the child was born. Godparents were essential components in this army whose ties were based more on loyalty than on discipline. Aguilar Mora astutely pointed out that “for Villa [. . .], family relationships were determinant, especially at the level of alliances based on extended family and regional origin.”

With Villa’s munitions network beginning to work and the army unified, he ordered the trains and cavalry to advance towards Chihuahua on October 30. Finally, after so much time assessing his enemy and having failed to lure him out of his stronghold, Villa accepted Mercado’s dare. The rebel army pitched its tents in a place called Estación Consuela, near Bachimba, and then in Armendáriz. There, having recovered from his wound during the fighting in Torreón, Manuel Madinabeytia rejoined Villa as an assistant with the high command.

On November 2, Villa sent a note to Mercado giving him twenty-four hours to surrender, otherwise, he demanded he come out into the open to fight “outside the city” in order to avoid civilian casualties. “From Ávalos to the south, the troops pick the ground that is best suited for battle and that was where me and my army will approach,” reported Villa. Mercado not only ignored Villa’s offer, but he also further fortified his positions in Chihuahua, his troops digging new trenches and foxholes. Villa’s scouts moved in and out of the city’s outskirts, confirming that Mercado’s troops were digging in and reporting rumors that Obregón had come to Sonora to join with Villa while Mercado was having problems concluding an agreement with Castro and the irregular Colorados. Even worse for Mercado, it was reported that Gen. Francisco Castro, who had arrived at the beginning of November to reinforce the Federales, had left Chihuahua and was on his way to the North to take command of Ciudad Juárez.

The day on which these rumors and messages arrived in Villa’s camp in El Charco (some twenty-five kilometers to the south of Chihuahua) was cold enough to wake the dead. The rebel army’s battle cry was “¡Viva la Revolución!” to which the men answered, “¡División del Norte!” Martín López spread the word that anyone who came asking for Villa should be immediately detained. Villa’s brigade, along with those of Toribio, Maclovio, Aguirre Benavides, Trinidad Rodríguez, Chao (who returned from Parral), and the Camargo’s Faithful led by Hernández, had all assembled. They were joined by hundreds of volunteers from all over Chihuahua, but they were unable to arm them.

And right in the middle of that crowded day, a notice was published stating that US President Wilson was considering intervening militarily in Mexico, using force to “restore order,” apparently with the support of congress. Villa didn’t appear to lend much weight to the news. His horizons were limited to Chihuahua.

Chihuahua had 40,000 inhabitants, anchoring a railway center leading north, while the Kansas City Railroad was constructing another line heading west towards Sonora. Gen. Salvador Mercado’s garrison numbered some 6,300 men with the battle-tested cavalry units of Orozco and José Inés Salazar—which ironically included Reyes Robinson, the captain who had mounted the provocation in Ciudad Juárez in 1911; plus, strategically-placed artillery, and a fortified perimeter built into the hills to the north, east, and south of the city.

The desertion of an ex-federal artillery captain named Rafael Torres, who had joined the rebels in Torreón, created a serious problem for the Villistas. He turned up in Chihuahua and presented a clear picture of Villa’s forces to Gen. Mercado (many fewer than Mercado had supposed), “little more than 5,000 and less than 10,000.” Villa later asserted that “The forces I brought with me for the attack on Chihuahua consisted of 5,600 men who were counted one by one during a review on the road to Jiménez.” Torres also told Gen. Mercado that Villa’s men had no more than 200 bullets a piece and artillery with no artillerymen, few shells, and poor organization.

However, Villa could also count on some useful information, continuously supplied to the rebels by peasants, friends, and infiltrators who provided clues as to what was happening in Chihuahua. During a council of war held at the Ávalos station on November 5, Villa had to admit that the attacking forces were inferior to those of Gen. Mercado and the enemy’s fortifications were formidable. Chao and Aguirre Benavides tried to convince Villa that the attack was a mistake. But Pancho had gone too far to turn back.

On November 5, at five o’clock in the afternoon, an immense line of 4,000 infantry from the Division of the North advanced in waves towards Chihuahua’s central plaza, hoping to force the Colorados cavalry out into the open to fight. The Villistas had cut off the city’s water supply earlier. As the infantry took their positions, Servín checked that the artillery guns were well positioned and the range to their targets properly calculated to make sure that he wasn’t going to fire a cannonade into his own men’s backs.

The initial attack that afternoon began from the south and east and moved towards the city. At the appointed hour, the troops shouted a unanimous ¡Viva Villa! but it was supplemented with cries of “Sons of bitches!” and “Hijos de su terrazuda nana” and “Sons of lowlifes!”

Gen. Mercado later commented that they attacked “with an unprecedented fury.” The rebels tried to move along the slopes of the hillsides, but electrified fences blocked their path. The positions taken up by the Villistas were not bad, but the federal artillery in the De la Cruz hills, which included four batteries, ravaged their lines and their own artillery. The Villista artillery directed by Servín was unable to respond because it lacked ammunition and sufficiently skilled artillery officers. Each time Servín positioned his artillery, the Federales pounded them. Despite this setback, the rebel infantry reached Chihuahua’s peripheral houses. This area was defended by old associates of Villa, Col. Rojas and Marcelo Caraveo, who were forced to retreat. It appeared that the defender’s lines might break, but Guillermo Landa’s Federale troops resisted, and the attackers were eventually thrown back.

Even so, the Villista’s first attacks were so vigorous that had it not been for José Inés Salazar’s cavalry’s nighttime counterattacks, the city would have been compromised. The Colorados knew what would happen if they were captured, so they threw everything they had into the fight. The artillery duel between the two sides continued from 10 p.m. to 3 a.m. The majority of Villa’s troops had never been exposed to serious cannon fire; it was a miracle that the columns did not scatter.

Within Chihuahua, friction between the regular and irregular troops continued to play out. According to Gen. Mercado, Orozco disappeared for twenty-four hours.

On November 6, the federal counterattack allowed them to recover positions they had previously lost, aided in their advance by artillery placed on Santa Rosa Hill. The Colorados’ cavalry kept up continuous sallies. And although the Villistas reached the city’s cemetery, the Federale artillery soon forced them to retreat, followed by new counterattacks from Orozco and the Federales’ Fifteenth Battalion.

Villa recounted: “While camped on one of the nearby hills, Col. Samuel Navarro approached and read to me one of the newspapers that had just been brought to us while a cannon on Santa Rosa Hill fired at us, each time more accurately. As he finished reading the most interesting parts, I moved away to give orders to the combatants when, just at the moment, Dr. Navarro was fatally injured by shrapnel from a projectile fired from a mile and a half away. Poor Navarro! But they still hadn’t hit me.” Navarro was the chief of the Division of the North’s medical services at the time of his death.

The news Villa was getting from Navarro when he was killed was very serious: the Federales had reoccupied Torreón. Villa had no rearguard. His territory was confined to the battlefield in front of him. More than ever, Villa was in no man’s land.

Perhaps under the force of these circumstances, Villa ordered Medina to launch a frontal assault, but the Federales concentrated their artillery and rifle fire, and the attack failed. Madinabeytia was wounded again and evacuated to Camargo. J.B. Vargas remembered that the action, “by its intensity and ferocity, and the enemy’s resistance, cost our forces more wounded men than during the previous days’ attacks.”

At seven o’clock in the evening, by the light of the moon, the Villistas advanced and seized two hills named El Grande and El Coronel that protected the city’s southern approach. The Laguna brigades took part in this action led by Aguirre Benavides, who had to put aside the bitterness from his run-in with Rodolfo Fierro in Torreón as well as gossip by some of the Chihuahuan rebels. Fierro went around saying that Aguirre Benavides and his troops were not worth a damn, calling him a chocolatero, a term coined by Villa to describe armchair soldiers who were only good for drinking hot chocolate. However, during the fighting in the hills, Aguirre silenced his detractors by demonstrating great courage.

In a world where bravado, disregard for life, and a love of risk abounded, Maclovio Herrera—distinguished by his fine features, large arching eyebrows, and enormous mustache—was labeled Herrera “the brave.” On November 7, el Sordo (as he was known) took charge of the offensive by attacking Chuvíscar dam and, despite counterattacks launched by Orozco, forced the Federales to retreat. Everyone spoke of Maclovio’s reckless bravery, fighting right out in the open with nowhere to take cover. At three o’clock in the afternoon, the Colorados and Federale cavalry moved towards the area near the dam. Maclovio’s brigade resisted their advance but were running out of ammunition. Maclovio, rifle in hand, prevented his brigade from collapsing in disarray and managed to organize an orderly retreat. Villa recalled that he had to call on Eugenio Aguirre Benavides’s brigade, once again, to extract Maclovio from his predicament, “which broke up our forces and disorganized my plan. So much so that for the remaining hours of light, all we could do was hold our forces together.”

The fighting continued on the hill De la Cruz into the night, but the Federales’ machine guns put a stop to any rebel progress.

Despite three days of continuous attacks, the rebels had not managed to break the Federales’ resistance. Villa became convinced that he couldn’t overwhelm the defenders’ reinforced positions and his ammunition was beginning to run out. He then ordered a general retreat and, under the cover of darkness, set up headquarters in Estación Alberto, thirty kilometers to the southeast of Chihuahua.

At sunrise on November 8, Federale cannons bombarded abandoned positions, not realizing that the Villistas had already withdrawn. When he realized what had happened, Gen. Mercado ordered Caraveo and Salazar’s cavalry units to pursue the rebels; they were later accompanied by infantry. Around eleven in the morning, the Colorados cavalry clashed with Ortega’s troops, who absorbed the first blows. Vargas explained, “they almost ran us over.” Villa exited the railway car where he was eating lunch and personally organized the reserve. They gathered ammunition from wounded rebels and from Contreras’ Laguna fighters and soon Maclovio Herrera and his brigade were back on the front line with 18,000 bullets for themselves and Toribio’s brigade. This counterattack forced the Colorados to retreat towards Chihuahua. But it was more a triumph than a victory, they had forestalled defeat.

By six in the afternoon on November 9, the Division of the North had been defeated, and if they kept pushing it, their entire force would be annihilated. They left behind very little ammunition or supplies as they had used it all up in five days of fighting. Gen. Mercado’s report (in which he lied with singular delight) claimed greatly-inflated Villista casualties: 800 dead, not counting those “buried at night” (the real number was probably around 400.) The press printed stories describing the most exotic slander now befalling the defeated rebels, claiming that “All the cadavers were well-dressed and wore silk undergarments” and “flags with ridiculous inscriptions” were collected from the dead. One particularly vicious piece reported that “In the most shameless way, the bandit Villa cheered up his rabble by doling out bottles of sotol [it’s, of course, impossible to imagine Villa, the rabid abstentionist, distributing alcohol to his troops] and telling them they would go pillaging for a month and could take the most beautiful woman they liked.” The Federale casualties were said to be 144.

In Gen. Mercado’s report, besides recognizing his artillery’s successes, he mentioned the Colorados who were key to the city’s defense: Orozco, Caraveo, and Salazar. Further, the local bourgeoisie had played a very important role under Alberto Terrazas and Enrique Cuilty, colonels of the irregular troops, along with the hacendados Falomir, Creel, and others who lent the army trams for the rapid mobilization of troops within the city. Having “obtained victory,” military bands roamed through the city streets where “enthusiasm was delirious.”

Rumors ran wild. Everyone claimed to have the right version of events. Some said that Villa had fled towards Sonora via Casas Grandes, others claimed he was still in the outskirts of the city, and he planned to starve it out by laying siege. Some said that Manuel Chao was dead, and that Villa was headed south, or that Villa was on his way north to Juárez. Gen. Castro, commander of the Ciudad Juárez garrison, started that very day digging trenches in the city while the victory in Chihuahua was celebrated with a parade and tolling bells.

Meanwhile, Villa was on the move towards El Charco, thirty kilometers to the northwest of Chihuahua. Federale scouts reported despondent rebel forces in very bad shape passing through towards the North without a clear destination. Salazar was in pursuit, no more than ten kilometers behind the defeated Division of the North.