twenty-six

1914

Ruins and Medals

When Villa returned to Chihuahua, he found a decree posted on the walls of the capital announcing that silver coins and bank notes would henceforth no longer be considered valid currency and could not be exchanged for Villista bills. Right away, the town’s usurers came out to complain and lodge their grievances. The government responded by making a concession, granting them several days in which they could conduct exchanges at the treasury. The rumor got out about this, and the treasury collection office collapsed under the weight of the rush. The goal of getting the new Villista currency into full circulation had been, nonetheless, achieved.

Meanwhile, if the Benton case were not enough, Villa received word that one of his associates, Manuel Baca, better known as el Mano Negra, had shot several people in the Santa Rosa hills outside of Chihuahua. One case pertained to a man by the name of Torres whom Villa had freed from detention but whose house and all belongings had been appropriated by Baca, who then shot him for motives of personal revenge. Just a few days prior, Pancho’s brother, the elder Antonio Villa, had intervened and prevented Baca from shooting some Colorados held by the Twelfth Regiment. Villa warned Baca that the next firing squad would be for him if such actions continued.

On February 22, Villa spoke publicly at a solemn ceremony in Chihuahua’s capital marking the assassination of Madero and Pino Suárez in the Theater of Heroes. “We will take Torreón with our teeth if necessary.” Villa must have thought better and changed his tone in mid-thought. “But I don’t think it will go like that. We are well armed and well provisioned; guided by Madero’s sacred spirit, we will prove invincible.” However, the campaign did not get immediately underway as Villa was preparing for his next belligerent fight at an unusually slow pace. Among other things, this was due to several pending ceremonies.

John Reed returned after spending some time with Urbina’s men in the south. He set himself up in El Paso to edit his dispatches and was on the scene while the Benton case was making waves. The day the scandal broke, he had been thinking of having his picture taken with Villa. “Tomorrow, I’m going to take a photo with him in uniform,” he wrote to his editor. “Don’t go spreading around that I’m an officer in this army, say that it’s like a joke [. . .]. The Mexicans don’t understand these things very well and I could end up getting kicked out of the country. And aside from that, I don’t want to pose as if I’m some sort of war hero when, in truth, I am not involved in the fighting.” Reed’s presence in Chihuahua allowed him to witness the ceremonies then underway.

Villa was to be decorated by the artillery officers in his army for valor on the battlefield. Reed described the reception room of the Chihuahua Government Palace in magisterial terms: “Brilliant chandeliers, heavy draperies, American wallpaper in gaudy colors,” four bands playing simultaneously. Villa arrived on foot: “He wore an old, simple khaki uniform missing several buttons. He shaved, wasn’t wearing a hat, and he hadn’t combed his hair. He walked quickly, a little bow-legged, with his hands in his pockets.” He looked disconcerted as he greeted a compadre here and there. Among the party and the chaos: the bands, cheers from the crowd, and artillery officers in their best uniforms. “Villa wavered for a moment, pulling at his mustache and looking quite annoyed.” Manuel Bauche recited (not really even reading) a speech with a plethora of metaphors. Officers extolled and flattered Villa, what we call lambisconear (sucking up) in Mexico. “And during all of this, Villa sat there downcast on the throne with his mouth hanging open, he examined everything in his surroundings with his small astute eyes. He yawned once or twice but, for the most part, appeared to be mulling over the situation with some intense internal amusement, like a small child in church asking what all of this is supposed to mean. He knew, of course, how to properly act and perhaps even felt a light touch of vanity [. . .] but at the same time, it bothered him.” He was given a medal and there were hurrahs and fanfares. Villa opened his mouth and let loose, “This is a miserable little thing to give a man in exchange for all the heroism you describe.” Many in the crowd heard this and his words deflated the audience a bit, but he played dumb in his speech, saying nothing more than that he couldn’t find any words and that his heart was with them. Then he gave the floor to Chao, elbowing him, who was the master of handling such situations.

However, later Villa let himself be photographed by Otis Aultman in Ciudad Juárez with his medal proudly on display. Bob McNellis said that Aultman was the only photographer Villa trusted. Villa poses in a half-length photo in a navy-blue uniform. Then three-quarter shots are followed by a series of photos: the first in the door of a house with Villa posing ramrod straight in a dark uniform, an onlooker has crept into the visual field half hidden behind a tree. One way or the other, Villa grew accustomed to the rituals of fame, although he had no idea what lay ahead. That same day, another photo was taken of him in uniform and wearing his medal alongside Luz Corral. Villa appeared extraordinarily serious.

Around this time, Pancho added another marital relation to those he kept up with Luz and Juanita. He met Guadalupe Coss, a Catholic girl from Ciudad Guerrero, Chihuahua. They say that her father was opposed to the relationship, but that Villa won her by playing cards. The Bishop of Chihuahua married them on Villa’s train.

Shortly thereafter, the general of the Division of the North participated in yet another ceremony, this one so full of meaning for him that it provoked tension throughout the city of Chihuahua only days before the march on Torreón commenced: Abraham González’s remains had been located and it was time to bring them to the city.

On February 25, Pancho Villa, accompanied by Gov. Manuel Chao and Abraham’s family members boarded a special train that retraced the path Abraham had followed the year before his death. The train collided with another in the station and Villa was thrown out of his compartment. He blamed Rodolfo Fierro, who had been drunk the previous day and had not made the proper preparations. Pancho fired Fierro as superintendent of the railways and, after detaining a passenger train in Juárez, ordered the passengers to disembark and for González’s procession to get on board. The train went as far as Estación Horcasitas.

Very little was left of Abraham, just bare bones of an incomplete skeleton. The identification had to be made by his clothing, wallet, a few cards, a checkbook with his handwriting, a few gray hairs, and a piece of greenish overcoat. Reed reported that “Villa stood silently beside the tomb as tears ran down his cheeks.”

They placed his remains in a white urn. Silvestre Terrazas, who had accompanied them, recalled, “Villa [. . .] while never letting the remains out of his sight, didn’t say a word. He just wept.” Thousands of people had congregated at the Chihuahua station. The men first carried the coffin on their shoulders to the house on Fourteenth Street. The multitude crowded around. Villa looked at them and with a dry “Stand back!” opened a path through.

A vigil was held for Abraham that night in the Theater of Heroes. Reed wrote, “The fact that Villa detested useless, pompous ceremonies made his presence at the public events all the more striking.” The coffin lay at the center of the stage. The vigil lasted two hours and featured speeches, children singing, and piano. Villa, “with his eyes fixed on the wooden coffin, didn’t move.” Suddenly, while Handel’s “Largo” was being played, Villa came down from his box, mounted the stage, picked up the urn, now in silence, and crossed with it over to the Palace, where the wake would be held. The crowd opened to let him pass. Villa arrived in the hall with the urn, “divested himself of his sword and threw it noisily into a corner. He took his rifle from the table and took his place in the first watch.”

There is a curious photograph from the event in the Government Palace depicting the Villista general staff: Maclovio Herrera, Toribio Ortega, Pancho Villa, José E. Rodríguez, Governor Manuel Chao, and Secretary of the Government Silvestre Terrazas. Their heads are uncovered, and their hats have been placed on the coffin. A gesture of respect? A final goodbye?

The funeral was held the following day. Bells and artillery salvos from the church towers and the Division of the North rang through the town. Ten thousand people gathered in Chihuahua. Villa refused to ride in a car, walking in the center of the funeral march amidst the dust kicked up by the procession. There is a photo showing the funeral coach pulled by black horses in which a hatless Villa can be seen walking behind the carriage in front of union banners. The coffin was flanked by a guard of men on foot. Pancho is lost amidst the crowd, alone. When they arrived at the Nuestra Señora de la Regla pantheon, Villa placed the coffin on his shoulders and helped carry it.

Commissioned by Pancho, Rosher, a member of the Mutual camera crew, filmed Abraham González’s funeral; however, as he didn’t have any film with him, he only pretended to do so by cranking the camera handle. Little did Rosher know what he was witnessing; what Villa considered so important did not interest the camera operator much. When he recalled the episode years later, he stated that the dead man had been run over by a train.

From this moment on, a feverish organizational commotion moved on down from the border to Chihuahua. During the last days of February, a flood of correspondence and telegrams passed from El Paso to Juárez to Chihuahua. Orders, suggestions, counter orders, offers. Lázaro de la Garza had informed Villa that Sommerfeld had obtained a 75mm cannon with 100 shells at $15 each and one hundred sixty boxes of munitions, all on their way by car via Alfonso Madero. Villa requested one hundred kilos of gunpowder. The next day, he insisted that the gunpowder then in El Paso under Raúl Madero’s name be quickly sent to Mexico. However, the gunpowder in El Paso was heavy grain and Villa needed fine grain which could only be secured in New York. He instructed De la Garza to acquire it without delay along with parts for the machine guns.

Villa was selling cotton and ixtle plant fiber but had halted cattle sales after prices fell. When De la Garza informed him that purchases were running ahead of sales, he sent $100,000 gold pesos with Hipólito.

Some voices insisted it was necessary to resume the embargo and, likewise, the elder Terrazas was pressuring US Customs through Cobb on the pretext of Luis junior’s detention. Villa’s agents were ordered to speed up deliveries and De la Garza reported to Villa that one million cartridges had been confiscated at the border; fortunately, they were to have been paid upon receipt. Thus, what ended up arriving in Juárez was one hundred rifles and fifty boxes of .30-40 bullets, two hundred Sheerlton rifles and a Colt 7mm machine gun, while one of two planes which had been purchased by Glenn H. Curtiss in California, a twin-engine two-seater, landed in El Paso. Raúl Madero recruited two pilots in the Orndorf Hotel in El Paso, Jefferson De Villa, hailing from Martinique, and Edwin Charles Parsons, a twenty-one-year-old US citizen who had worked as a cowboy and a miner, at salaries of $250 and $200 per month, respectively.

Hipólito was the prime mover behind the newly-hatched Villista air force but Pancho didn’t seem to share his enthusiasm. A few days later, “his pilots informed him that they could not fly over the Chihuahuan mountains because of poor visibility owing to fog. Villa disagreed with them, insisting that if he could see well enough to cross the mountains on a horse, they should be able to do the same in their airplanes.”

By the end of February 1914, Villa was locked in an intense correspondence with the Finance Agency, intent on buying all manner of goods. He urgently needed artillery materials (February 23), including cartridges, gunpowder, and wire; he sent $2,000 to purchase boots in El Paso (February 24); he urged Raúl Madero to secure gunpowder to manufacture bombs, as well as cartridges, nitroglycerin (February 26), uniforms and boots from Krupp (February 27), and finally more rifles, bullets, and gunpowder (February 28). At long last, on the last day of February, Lázaro de la Garza reported to Villa by telegram that he would send him the airplane and announced that he could now pay all the bills. Villa then cut off the expenditures: “We are in no condition to make payments except for what is absolutely indispensable,” that is, munitions and provisions, ordering that only purchases along these lines continue. Over the next few days, he attempted to bring some order to his purchasing agents, mandating that they buy only Mauser .30-40 ammunition because all the orders for munitions of different calibers were creating havoc. Meanwhile, the cannons the Villistas had captured at the end of their last campaign were being repaired in the workshops of the Compañía Industrial Mexicana. Many of them didn’t work because the Huertistas had carried off the breeches. Villa believed the cannons would be the key to the coming battle in Torreón. The correspondence between El Paso and Juárez was particularly busy during the first two weeks of March. Villa or Chao—who as governor had assumed the task of organizing the Division of the North’s rearguard—requested acid and detonators and sent the money to pay for them. They asked for revolvers and gunpowder and tried to sell cattle in the US as well as ordering ammunition and saddles. They bought used pistols and apparently achieved a great success when Lázaro de la Garza sent one thousand pounds of gunpowder on March 6. Among the correspondence that reached Villa, the Rio Grande Valley Bank & Trust Co. of El Paso informed him that the Bank of London in Torreón had refused to honor the check he had given to the former after the first battle in La Laguna, claiming that it had been obtained through force. This gave Villa one more reason to go to Torreón.

And while he was provisioning the Division, Pancho began to dictate the story of his life to Bauche Alcalde with Trillo writing it out in shorthand. Bauche dated the prologue February 27. “The tragedy of my life began…”

During this time, Villa maintained a relationship with María Dominga de Ramos Barraza, whose matchmaking aunt brought her to Villa from Jiménez. The girl later wanted to marry and languished in sadness, but for once, Villa refused as his matrimonial situation already seemed too complicated. He said, no one forced you, “you sought out my presence with your own steps,” and declined to marry her. They would have a son named Miguel in January 1915.

In the early days of March, John Reed, who was then in Nogales, was hearing comments from Carranza’s circle such as “As a fighting man, Villa has done very well for sure. But he should not try to involve himself in governmental affairs because, after all, you know, Villa is just an ignorant peon.”

Chao, who generally downplayed his work as governor, attributing it to Villa, continued revolutionizing Chihuahua. He published a decree for the distribution of land to widows, disabled veterans, and orphans by breaking up certain haciendas and sharing it out in 25-hectare farms which could not be sold for ten years, and which could not be foreclosed on because of personal debts. On March 14, Villa reviewed the medical brigade, which included the mobile hospital created and directed by Dr. Andrés Villareal, who had studied at Johns Hopkins University. It was a train that had a large operating room and could attend to up to 1,400 patients. Everything seemed ready.

It was during this time in Chihuahua when Villa’s guard and the Shock Brigade assumed more important dimensions, earning themselves a mythical air. Jesús M. Ríos received command of the Scout Corps under Maj. Sáenz and established their headquarters in the old Rurales’ barracks. Villa ordered them to organize a stable for 600 horses, two for each man, and directed them to adopt a new uniform: a Stetson 5x hat and an olive-green hunting jacket. They had their own shop that made saddles and matizas, knee-length chaps. They were armed with Mauser 7mm rifles and Colt .44 pistols, and the new squad began to be called Los Dorados, the Golden Ones.

If there’s anything that helped thicken the veil of fog surrounding Villismo, it’s the origins of the term Dorados. Versions abound. J. B. Vargas stated that Villa took the name from bandits called the silver ones in Altamirano’s novel El Zarco which Puente had told him about one time. However, Puente would not become one of Villa’s confidants until much later. Some say the name came from the khaki hunting jackets (they were pine colored) they wore, but at first, they wore green ones. Only later did they adopt the khaki uniforms, which didn’t stop some from insisting the term owed itself to the perception that “the clicot uniforms [. . .] appeared golden in the light of the sun.” Ignacio Muñoz claimed the designation was for the metallic ribbon they wore on the front of their Texan hats, or that’s what a “warrant officer” told him anyway. As it turns out, in a photo taken a year later, the Dorados were still not using Texan hats, most of them used huaripa and cowboy hats. J.B. Vargas offered still another explanation: they were called Dorados because of the gold coins spent freely, which is hard to believe because they had little money at the time, never mind any gold. Juan B. Muñoz asserted that the Villa brigade, along with the entire Division, marched in review in Torreón soon after the Battle of Zacatecas and that Trinidad Rodríguez’s guard carried a standard with the lettering: “The Guard of Trinidad Rodríguez, Dorados,” and that Villa said to Trini that he was going to steal the name for his own guard. Rodríguez replied that was fine with him and that he would call his own Plateados (the Silver Ones), which Urbina’s men ended up adopting. The fact is that, months before any of these theories were hatched, the Dorados (already going by this name) had had their baptism in blood in Torreón.

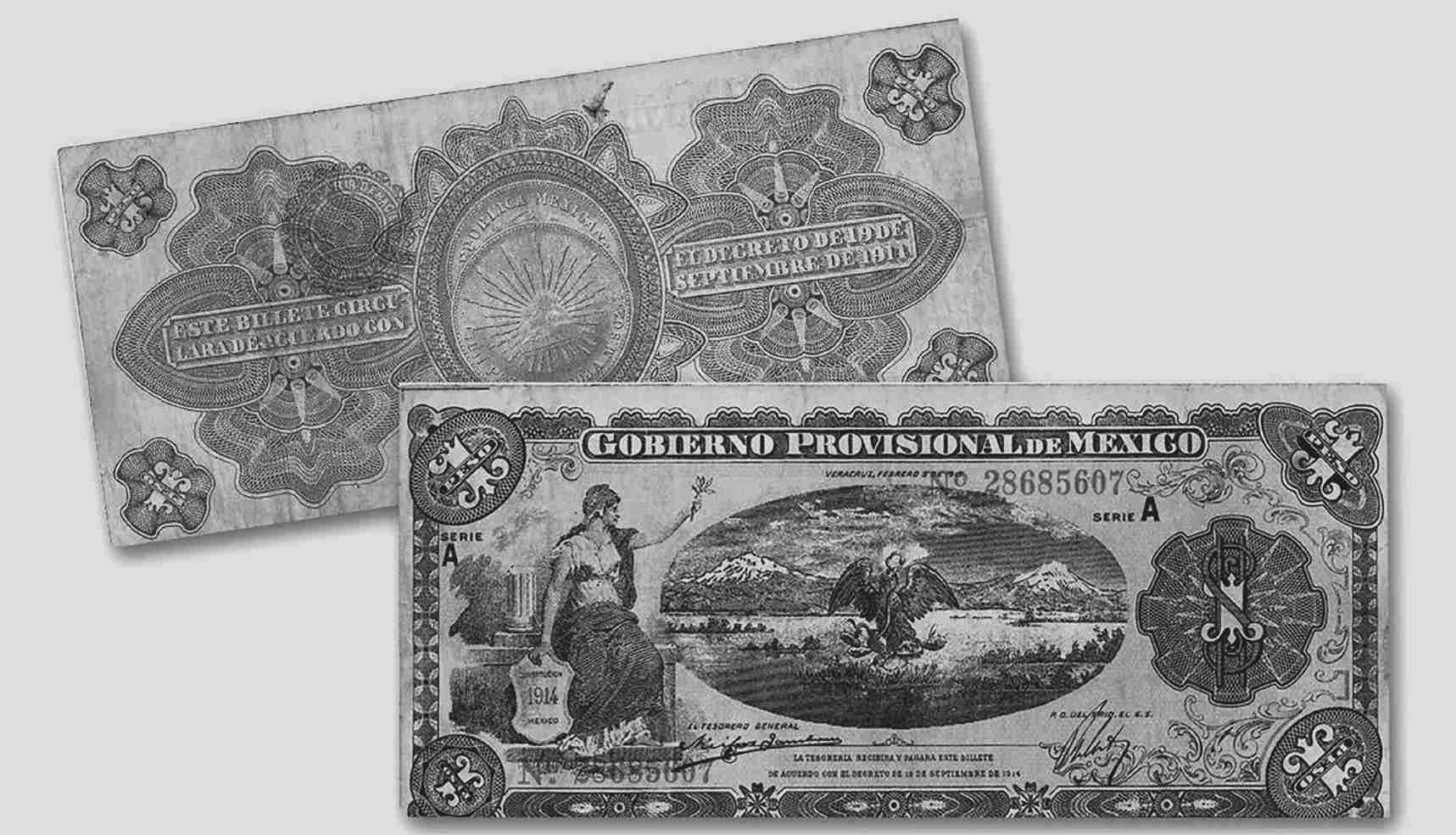

Peso banknotes printed by the Provisional Government of Mexico during the revolution. These banknotes were sometimes called Pancho Villa’s “blankets” and they were printed as more funding for the Mexican Revolution was needed. Veracruz, 1915.