thirty-eight

sidewalks

Emiliano Zapata, unaccompanied by his troops, entered Mexico City by train on November 26, 1914, and registered at the San Lázaro hotel. He issued a few sparing comments to the press, “My people and I are in complete agreement with Gen. Villa [. . .]. I didn’t want to get to the capital before Gen. Francisco Villa.” A few days later, November 28, Zapata retired to Morelos, explaining that he might have to fight all the way to Puebla. Was this a sign of suspicion? A lack of confidence?

That same day, Felipe Ángeles arrived in Mexico City with 6,000 men, the vanguard of the Division of the North. He set himself up in the Los Morales hacienda and immediately declared that he didn’t want to enter the capital, as it would only “be claiming for myself the applause and honors in which I have no interest.” Soon after, he received instructions from Villa ordering him to deal harshly with any looting, even stricter than the Zapatistas had issued two days prior.

Federico Cervantes talked to his friends in Ángeles’ high command about “the strolls we would take in the capital. Gen. Ángeles heard what I said and turned to me with a benevolent smile to say I was wrong; within three days we would march on Veracruz in order to put an end to the campaign.”

The Division of the North’s trains were arriving one by one and parking themselves between Tacuba and the Morales hacienda. On December 2, Villa’s train arrived in Tacuba on the outskirts of Mexico City. It was obvious that Villa was delaying his troops’ entrance into Mexico City out of courtesy towards the Zapatistas, and they were returning the favor. The new allies were feeling each other out.

Osuna snapped a series of photographs from Pancho’s railway car, one of which shows Villa was wearing a pith helmet. The Dorados were decked out in new uniforms and wide-brimmed Texan hats. Villa showed off his helmet, even if wearing such headgear would be prohibited by José Isabel Robles, the Minister of War, a few days later. Robles consigned huaripas and military caps to the past, allowing only Texan and cowboy hats, which had been worn by the Convencionista army. Obviously, no one paid any attention to the order, especially as the Casa del Obrero Internacional (International Workers House), was now providing the northern generals with hats and clothing. Onlookers and the curious crowded together at the train station to catch a glimpse of Villa. A large entourage rode in the general staff’s train, including Malváez, the editor of the Villista newspaper Vida Nueva, many photographers, Baca Valles, George Carothers—who had attached his car to Villa’s train—and Gen. José Rodríguez. There is even a photo in which we see Villa attending to a crowd while, alone and absolutely isolated, Gen. Tomás Urbina contemplates the scene from a window. Besides the photographs, there are also films preserving for history brief clips of Villa—who doesn’t know how to act on camera—rubbing his hands together and snapping his fingers.

On that same December 2, Villa received a note from Zapata proposing a meeting between the two. Gen. Abel Serratos recalled that Villa sent for him to talk things over. One of his agents had reported that the southerners were very suspicious that Zapata had met up in a bank with three of his generals, and that they were inclined to withdraw to Morelos to break up the alliance. Serratos remarked that there were a great many intrigues playing out inside the Zapatista camp.

Villa then decided to send Roque González Garza to Morelos with Juan Banderas and Serratos. Although he was not invited, George Carothers attached himself to this group. They delivered a personal letter from Villa to Zapata in which he “assured his sincerity.” Zapata replied by inviting Villa to a meeting in Xochimilco.

On December 3, President Eulalio Gutiérrez arrived, his train stationing itself close to Villa’s. The two then held a meeting. Vito Alessio Robles was called in to consult with them and related that when he went to board the train a woman approached him asking him to intercede to prevent her husband, Reyes Retana, from being shot. But the shots could already be heard nearby. Villa and Eulalio later told him that he was a counterfeiter and that presses and plates had been found in his house. It seemed that they had agreed to executing Retana. Then and there, Gutiérrez named Vito Alessio, despite his objections, to the city’s chief of police, “a nightmare of a job.”

Vasconcelos provided an absolutely different, quite inexact, version of events. He claimed that he intervened to defend the counterfeiters and went to see Eulalio, who told him that relations with Villa were touchy. Villa’s car was located some five hundred meters from the presidential car and when Vasconcelos arrived, the guards prevented him from entering because Villa was sleeping—it was ten o’clock in the morning and Villa was probably then meeting with Gutiérrez and Vito Alessio. While he was arguing with the guards, the firing squad let loose, “I cussed out Villa and swore that I hated him!” In the end the Nájera for whom Vasconcelos had come to intercede turned out to be guilty. What’s clear is that he had presented Vasconcelos with a gold watch, paid for with the counterfeit pesos. Villa put it more matter-of-factly. “The counterfeiters are from good families, or at least they have the same names.” He sent them to a court-martial, and they were shot at ten o’clock in the morning. He had no sympathy for them, rich men who were trying to game the war economy. He didn’t blink an eye.

Villa accompanied Eulalio to the National Palace at five o’clock in the afternoon, but he left him off at the elevator as he did not want to enter the Palace without first talking to Zapata. There is an interesting photograph of both men. Villa is in profile, wearing a rough wool sweater and his pith helmet, while Gutiérrez’s back is to the camera. According to some sources, problems would arise in the Palace between Eulalio and Eufemio Zapata because of some lack of courtesy. Upon returning to the city, Villa must have seen the posters sending off the Carrancistas, pasted on the walls by orders of Salvador Alvarado, featuring a picture of Villa when he was a prisoner in 1912.

The following day, December 4, Pancho Villa left Tacuba in an automobile at eight o’clock in the morning, drove through San Antonio Abad and Tlalpan, and arrived in Xochimilco at 12:10 p.m. Roque González Garza, José Isabel Robles, Rodolfo Fierro, Enrique Pérez Rul, Madinabeytia, Agustín Estrada, Nicolás Fernández, and a small guard of Dorados came along. Their slogan was, “not one drink of liquor for us.” Carothers and Canova went along representing the United States, whether by invitation or not.

They were met by fireworks, musical bands playing fanfares, big crowds, and children carrying flowers. Villa, as was his custom, couldn’t help but be moved and shared everything he had in his pockets with the children. Otilio Montaño embraced them at the municipal building on Juárez Street to cheers and bravos shouted from the crowd. Soon after, Zapata arrived by car from the Cuernavaca highway. According to Serratos, they shook hands in the plaza before embracing. “A handshake of friendship.” Canova stated that Villa wore no jewelry whatsoever, while Zapata wore two gold rings on his left hand.

The meeting took place during a meal in Manuel Fuentes’ house at 4 Hidalgo Street. The conversation was recorded in shorthand by Gonzalo Atayde, Roque González Garza’s secretary. In what Vito Alessio would describe, in a slightly patronizing tone, as a discussion among two old peons, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, in their first face-to-face meeting, felt each other out.

Only Roque González Garza joined Villa during this first meeting. He was an old-school Maderista and had been Villa’s voice at the Convention. Villa didn’t want the intellectuals at his side, he wanted to hold the meeting without any hindrances or mediations. Zapata, on the other hand, brought along Paulino Martínez, Alfredo Serratos, Alberto S. Pina, his brother Eufemio, Palafox, and Banderas (el Agachado), who later gave up his chair to Capt. Manuel Aiza, Amador Salazar, two women (one of whom was his sister María de Jesús), and a small boy, his son Nicolás. Although he was often at a loss for words, it was as if this were a reunion and he wanted to welcome Villa into the family.

It was a somewhat wily conversation that even included a few misunderstandings. It varied between brutal directness and ambiguity, frank truths and weighing up the other side, personal testimonials interrupted by vague questions.

After Villa pointed out that he was always worried that the Zapatistas “would be forgotten,” marginalized in the revolutionary process, Zapata added quickly, “The compañeros have already told you: I always say, I always tell them, that Carranza is a bastard,” a conclusion they shared without hesitation.

“They are men who sleep on soft pillows. How are they going to be friends with a people who have spent their whole lives suffering?” asked Villa.

“On the contrary, they are used to being the whip against the people,” affirmed Zapata.

Then Pancho laid out what would have happened if the Carrancistas won:

“There would have been no progress, no well-being, no land distribution under these men, rather, only tyranny in the country. Because, as you know, tyranny comes with intelligence and intelligence is tyranny itself, because it has to dominate [perhaps Villa was thinking of the long dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz and his “Científico” advisors]. But their tyranny would be the tyranny of fools and it would spell the death of the country.”

Then, after recounting various stories about how little those from the Division of the Northeast, and how much the Division of the North, had fought, during which Zapata hardly interrupted him, Villa got to the heart of the matter.

“We’ll see if our fates are sealed here in Mexico, and we’ll see if we go where we’re needed,” said Villa.

“That’s all in both of your hands,” added Serratos, playing the part of what we call a kiss-ass in Mexico.

A dialogue followed in which Zapata and Villa thought about their own roles and how the great festival was progressing.

“I don’t need any public position because I don’t know how to manage such things. We’ll see where those people are. We are simply going to charge them with not giving out chores,” said Villa. Was he thinking about Carranza and Zacatecas? Was he saying they would monitor how those they put in power conducted themselves and stayed out of military affairs?

“I warn all my friends about this, that they be very careful, if not, the machete will come down on them,” answered Zapata. Was he thinking about how power corrupts and how it is necessary to tie those who hold it on a short leash, even if they might be old friends?

The secretary noted the laughter in shorthand.

“I believe that we will not be fooled. We have confined ourselves to corralling them, to taking care, great care, on the one hand and, on the other, to herding them around.”

But Villa was on a roll, “It’s very clear to me that we are fighting the war, the uneducated men, and that the government cabinets have to take advantage of it; but they won’t give us any duties.”

Zapata replied, “The men who have worked the hardest are those who have the least use for sidewalks. Nothing but sidewalks. I say to myself, they’re so long that I walk until I want to fall down.” By sidewalks, Zapata meant Mexico City.

“This ranch is too big for us,” seconded Villa, referring to Mexico City now as a ranch.

Then they talked about the coming war, with Villa offering to take charge of “the campaign in the North,” declaring he would fight “for the bulls of Tepehuanes and for the horses from up there too.”

After remarking that the enemy would limit itself to defending Carranza as a figurehead, Villa said, “I don’t see anything about the nation.” He recalled that during the Convention they asked for his resignation and that “I was dragged through the mud,” although it wouldn’t be a terrible idea “to settle all our accounts” in order to retire because “I have some small plots that aren’t from the Revolution.” He then continued on without any transition to the problem of land reform.

“My dream is to divide up the lands of the rich. God help me,” he said, mocking himself. “Are there any of those here?”

The secretary recorded several voices affirming, “the people, the people.”

“Well, then, we want little pieces of land for the people. But as soon as the land is divided up, the game of taking it back from them will begin,” he added in an attack of pessimism.

“They really love the land,” added Zapata. “They still don’t believe it when they are told ‘This land is yours.’ They think it’s a dream.”

“Our people have not known justice, not even freedom. The rich hold all the largest territories. And the little guy, without a shirt on his back, works from dawn to dusk. I believe that a new life will come from what happens next, and if not, we’re not going to give up our Mausers.”

The main part of the conversation ended with Villa telling Zapata that he had 16 million cartridges, 40,000 Mausers, and seventy-seven canons.

“Because as soon as I saw that this man [Carranza] was a bastard, I set myself to buying ammunition,” explained Villa.

“These bastards see what’s happening and then, all of a sudden, they want to join in and rush to the rising sun,” Zapata added. “But a lot of them will go to hell when the sun really rises!”

It seemed they were beginning to get along well. Villa told Zapata that he had “Finally met the real men of the people,” and Zapata told Villa that “I celebrate meeting a man who really knows how to fight.”

Villa offered Zapata a drink from his glass of water. Zapata politely declined; he must have thought Villa was crazy.

Next, they talked about Zapata’s cowboy hat (“I’ve only come across one of these”) and Villa’s pith helmet, which was called at the time, who knows why, a Russian cap; they talked of Orozco and his father (“What a shame that Orozco wasn’t around because I’d like to see him”), and of the years they had spent fighting. Villa said he’d been fighting for twenty-two years, stretching his view of the time he’d spent confronting the system all the way back to 1892, when he was fourteen years old. He included the entire time he’d spent as a bandit, making it part of “the fight.” Zapata said he began when he was eighteen.

León Canova, a special envoy for Woodrow Wilson, was present for the talks—even if he was at somewhat of a distance—and filed an official report for the State Department, giving a description of Villa, “Villa is tall, robust, weights around ninety kilos, and his skin is ruddy like a German.” He was not pleased by Zapata’s appearance.

At the end of the meal, Zapata raised a toast with a tequila, drinking half of it and then offering the cup to Villa who didn’t dare refuse, so he wet his lips. The matter produced a variety of versions and polemics. Blanco Moheno claimed it was mezcal. “One isn’t going to kill me in exchange for the pleasure of being here with you, Gen. Zapata.” Quirk stated that Zapata sent for a bottle of cognac at the end of their conversation, while Villa asked for a glass of water. Zapata didn’t take Villa’s request seriously and poured out two glasses of the liquor, proposing a toast to the union of the two campesino armies, from the North and the South. Villa, hesitating, took a sip and almost choked, his eyes filled up with tears and he, once again, asked for a glass of water.

In Xochimilco, Villa discovered southern food: turkey mole, tamales, and beans seasoned with epazote and green chilis. It seems he maintained a love of this food for the rest of his life and Zapata sent corn and spices to the north over the following months, including a mill for nixtamal—partially cooked masa treated with lime—a shipment of assorted chilis, and fragrant herbs.

At around two o’clock in the afternoon, they left the room because a band was playing so loudly that it was nearly impossible to continue talking. They stepped into an adjoining assembly hall, walking arm in arm, accompanied by Palafox, where they remained for an hour.

Roque González Garza recalled that Villa told him that he and Zapata had concluded a pact comprised of four points: 1) A formal military alliance between the Division of the North and the Liberation Army of the South; 2) Adoption of the Plan de Ayala by the northerners, excluding the plan’s attacks on Madero; 3) Villa would provide arms and ammunition to the Zapatistas, and 4) Support for a civilian president of the republic.

Zapata and Villa embraced, and tears flowed when they parted. The meeting had finally taken place.

On December 5, Eulalio formed his government, vacillating and marking time. The paradox was that he was president owing to the votes of those who were now fighting him. Lucio Blanco served as Minister of the Interior, José Vasconcelos as Minister of Public Education, José Isabel Robles as Minister of War with Eugenio Aguirre Benavides acting as undersecretary, Chao as governor of the Federal District of Mexico City, Vito Alessio Robles as chief of police, Felícitos Villarreal as Minister of Finance, the Zapatista Palafox as Minister of Agriculture, Rodrigo Gómez as Minister of Justice, Valentín Gama as Minister of Commerce, Mateo Almanza as commander of the Mexico City garrison, and García Aragón as Commissioner of the National Palace.

At long last, on Sunday, December 6, the men of the Convention, the Zapatistas, the Villistas, and those who were beginning to identify themselves as a third force, all entered Mexico City and paraded through its streets. The Zapatistas left from Tlalpan, and from their barracks in San Lázaro and San Ángel, while the Villistas arrived from Tacuba and the Morales hacienda. They met up on Verónica avenue—today it’s called Melchor Ocampo. Villa wore a dark uniform, some described it as olive colored, others called it marine blue, and his kepi. Zapata dressed as a charro with a Mexican eagle surrounded by a golden border on the back of his yellow jacket. They did not enter on foot, nor by auto, trolley, or carriage. The southerners, the Division of the North, and the Convencionistas all rode in on horseback. Ángeles was nowhere to be seen along the parade route as he took charge of logistics for the Division of the North and organized the distribution of its brigades.

They advanced along the avenues of Tlacopan, Rosales, Reforma, Juárez, and San Francisco—which would be renamed Madero a few days later—before arriving at the National Palace in the Zócalo where Eulalio Guzmán and his cabinet waited for them. Thousands of handkerchiefs waved, and thousands of onlookers crowded around. As Villa put it, “never seen before.”

Thanks to one photograph, supposedly taken by Casasola, the author of this book has been able to identify the generals who head up the procession on San Francisco avenue. Just behind the Zapatista buglers on small horses, Lucio Blanco, is looking at a clock that reads 12:10 p.m. In the second row, Otilio Montaño is observing the balconies off to his left, his forehead still wrapped in a bandage from his most recent wound. There is the very young Rafael Buelna. Urbina, with a steely gaze, is up front in a salacot. Zapata and Villa (who rides along conversing with Emiliano), and between them is Everardo González, while off to his right is Rodolfo Fierro on a white horse with a cigar in his hand and defiant look. In the right corner we see Villa’s secretary, Luis Aguirre Benavides, while Madinabeytia and Pérez Rul are off to the right and out of the frame in many versions of the photo. Just five years earlier, of the eight generals who led the march, there was a rural schoolteacher, a student, a cattle thief, a horse wrangler, a gunslinger, a train engineer, and two campesinos. No one can explain the Mexican Revolution without explaining this picture. It is necessary to understand those in the photo as well as those who are not in it. Most emphatically, one must note the absence of the educated and radicalized middle class. Where are the journalists, the doctors, the professors? Unlike other contemporary revolutionary processes, the campesinos and workers here had no need for intermediaries or translators.

Lucio Blanco’s situation was unique. He had managed to pull a section of Obregonismo’s cavalry behind him from the Division of the Northeast while also having become famous for carrying out the first land reform. When Carranza left the capital, he found himself in the most ambiguous of circumstances. Thus, he took over the Federal District’s government based in Mexico City, insisting on enforcing the agreements reached in Aguascalientes with respect to the removal of both Carranza and Villa, going so far as to say that he would resist the Convention by force of arms if Villa was not retired. But he was out of time. In the end, he accepted the inevitability of the outcome and, after being named Secretary of the Interior by Eulalio, joined in the parade.

Eufemio Zapata rode just behind the lead contingent, opening the way for the Zapatista brigades. Next in line came Ángeles and Raúl Madero directing the Division of the North. Ramírez Plancarte noted the Zapatista’s martial inadequacy and the Division of the North’s surprising discipline, which seemed to him far superior to that of the Carrancistas. He admired the Villista’s sweaters and fringed leather jackets “which gave them the ferocious look of Comanche” and the bandannas around their necks. The Villistas looked over the Zapatistas. Victorio de Anda observed, “There were some rough looking horses, but they had a lot of heart.” The parade lasted for six long and brilliant hours during which sixty-six cannons rolled past. Gilberto Nava happily remarked, “Everyone loved the Division of the North.”

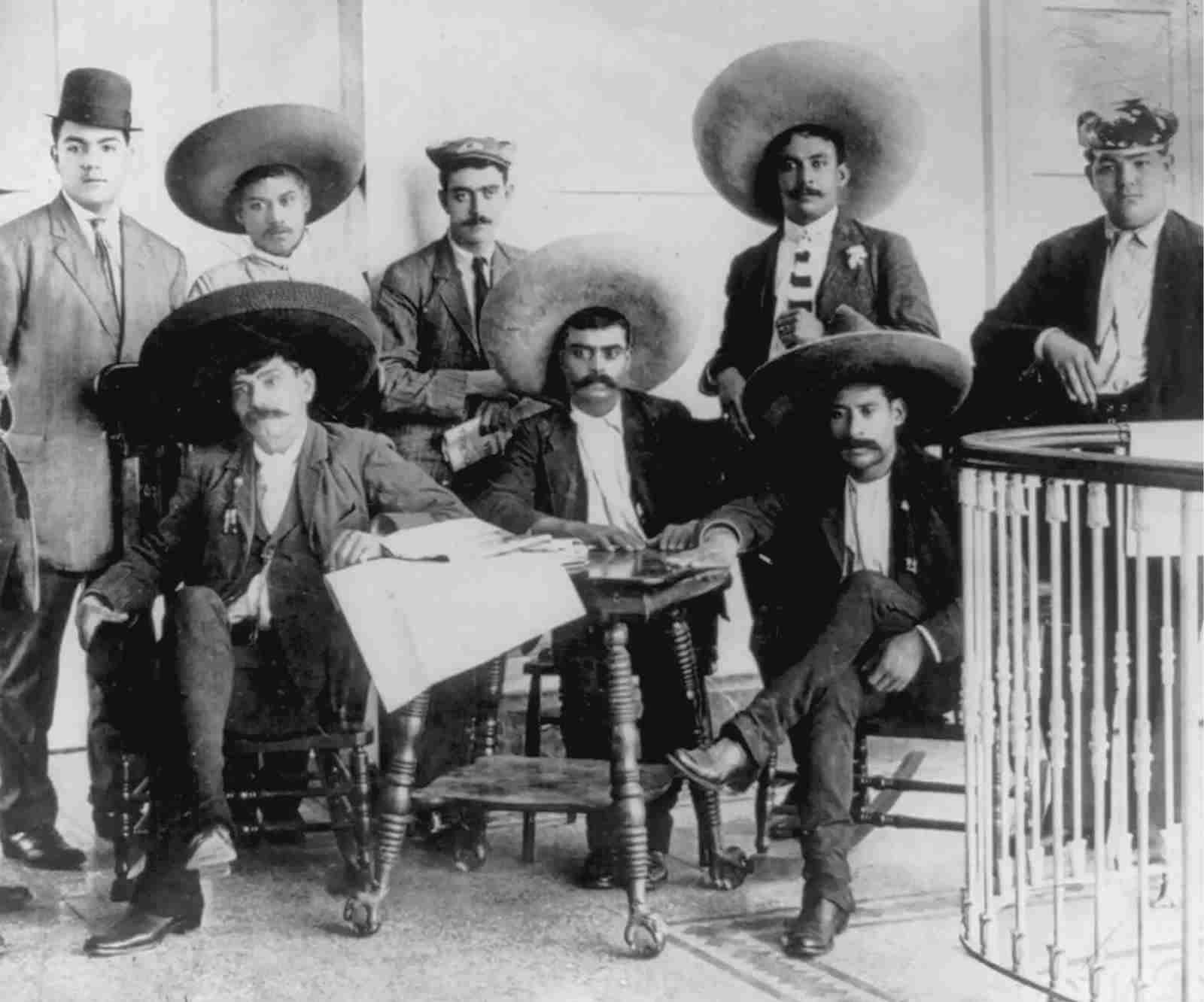

Upon arriving at the Palace to meet Eulalio Gutiérrez, Zapata and Villa passed through a hall where four comfortable chairs were pushed against a wall on which there was a mural that this author has not been able to identify. Among the chairs, one in particular stood out with its gold and arabesque decorations and Maximiliano’s imperial eagle adorning its back. Gómez Morín described it gracefully thus, “Compared inch for inch with other chairs, it is relatively small, but its cracked stucco carvings, its threadbare burgundy velvet upholstery, and its chipped, golden garland indicates its long-running service.” At any rate, someone discovered the chair and brought it out. Who came up with the idea for a photo? The photographers who were accompanying them? Villa? Zapata? Both? Mraz thinks that the picture “was carefully staged, not by Casasola [even if he took it], but by Villa and/or Zapata.” Rito Rodríguez stated that it was Villa’s idea, that he sent for a photographer and, when he appeared, told him, “Wait a minute, my friend,” so he had time to lean in a little before the shot was taken.

The following conversation was said to have taken place between the two generals:

“Sit down, sir,” said Villa.

“No, you sit, my general,” replied Zapata, to which Villa must have acceded.

Cecilio Robles, an old Villista, offered a simpler version. He recalled that Villa said, “I’m going to be the president of the republic for a bit,” and he sat himself down in the chair.

The photo itself, aside from the long symbolic debate it has provoked, is interesting. Villa is seated and lounging in the aforementioned chair; he’s wearing a dark-colored uniform and leather chaps. Zapata, seated to Villa’s right from the camera’s point of view, is looking at the camera with a sad and watery gaze that so frequently characterized his personality. Also seated—and flanking the two generals—is Urbina, to Villa’s left, with his dark eyes and a shock of unruly hair. Otilio Montaño, his forehead still bandaged, is to Zapata’s right. Standing nearby, Rodolfo Fierro just sneaks into the photo’s far right margin, tilting his head timidly with his hat in his hand.

There is a second, less popular version of the photograph. In it, Zapata is talking to Villa, who seems fascinated by Emiliano’s charro hat resting on his knee. Villa, who went crazy for hats, must have been in shock at the sight of the southerner’s hat, a “wide-brimmed hat made from rabbit hide called a twenty-ouncer.”

What makes these photographs unique, aside from the chair, are the bystanders. All of Mexico’s grandiosity is on display: from the boy over Zapata’s shoulder with his mouth open and his eyes shut, to the distracted-looking gringo wearing thick glasses but dressed up like a charro—who no one has ever been able to identify—to the black-skinned man with cartridge belts slung over his chest, to the character with a lost look off to Urbina’s left, to the woman standing near the back of Villa’s chair—who appears to be an out-of-place office worker—to the onlookers who are barely visible in the third row. The photo captures the marvelous and baroque family that the revolution raised up from anonymity.

Eufemio Zapata had previously declared, “I made just one promise to my soldiers: upon taking the capital of the republic, I would immediately burn the presidential chair because all the men who occupy this seat, which seems to be hexed, forget the promises they’ve made the moment they sit down [. . .]. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to fulfill my promise since I found out that Don Venustiano Carranza has carried off the chair.” Villa confirmed this when he stated that he and Zapata “were joking in the National Palace about the vanities that Carranza carried off to Veracruz along with the presidential chair.” Eufemio later confessed to Martín Luis Guzmán that until he saw it, he didn’t realize his mistake because he had always believed the presidential seat was a saddle, the word being the same in Spanish.

But what chair are we talking about? If Venustiano Carranza had taken the presidential seat to Veracruz, whose chair was that in the picture with Villa and Zapata? We can start from the assumption that there were several chairs. If so, which one was this? Vito Alessio Robles seemed to clarify the matter when he recalled that there was “a presidential chair” in one of the Palace’s halls. “I was informed that it was a historical relic that ought to be in a museum.” Francisco Muro, another Villista, asked himself, “Is this chair what so many were fighting for?”

There was never a great reception hall centered around a presidential chair in Republican Mexico, including during the times of Díaz. If such a seat existed, it was just one among many plain old chairs in which Madero, Huerta, or Carranza could be seen, intended for use in an office, a dining room, around a meeting table, or set up in a box along a parade route. So, what exactly was Venustiano supposed to have carried off to Veracruz? Nothing but a myth. And Eufemio wanted to burn that myth. As it turned out, Pancho and Emiliano created the myth itself with an invented seat and then stripped Carranza of it in a snapshot. Curiously enough, it was the symbolic chair that neither Villa nor Zapata wanted for themselves.

The photo was published much later because, at the time, there were no newspapers in the city; however, once made public, this image centered around a non-existent presidential seat, gave rise to a collective memory of “the presidential chair.” This chair became a reference point which influenced Mexican thought for the next one hundred years: the idea of fighting for the chair, the image of the chair as the center of the country, as the top of the pyramid, as the center of power.

Although the parade went on until five in the afternoon, Eulalio Gutiérrez offered up a meal in one of the halls of the National Palace at two o’clock. The president sat in the place of honor with Pancho Villa to his right and Zapata to his left, who, from the distant and gloomy look on his face, was none too pleased by the honor. Eulalio placed the new Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, at Villa’s side and sat Felícitos Villarreal, the Minister of Finance, to Zapata’s right. As always, there is a second row standing behind the men seated at the table dining, a motley crew of bodyguards, waiters, and onlookers.

Zapata came across Gen. Guillermo García Aragón at the banquet, the Commissioner of the National Palace, who eagerly extended his hand. Zapata refused to greet him. The southern general was “very troubled” by his presence during the meal. García Aragón had fought under his command, but then went over to Huertismo with his whole contingent. When Huerta fell, he then changed colors once again and joined the Convention in Aguascalientes. Another source of tension was the piercing looks that short-haired Zapatista Gen. Juan M. Banderas was shooting at Vasconcelos, whom he threatened to kill through gritted teeth. “He messed with me while I was a prisoner. I swear that not two days passed by without him screwing me over.” Banderas, a Maderista from the start, had been governor of Sinaloa, but Madero had dismissed him “for his excesses” and imprisoned him. He was freed by Huerta during the invasion of Veracruz but clashed with him and subsequently joined up with Zapatismo. Vasconcelos brought the banquet to a close by praising the two main guests. Martín Luis Guzmán preserved one of his turns of phrase, “Pancho Villa and Zapata, by eating together at this table, commit themselves to the union of the people.”

The following day, Monday, December 7, a meeting was held to work through some matters pertaining to the war. Eulalio, along with José Isabel Robles, the Minister of War, met with the Zapatistas. Villa was also invited to the meeting and arrived at 1 p.m. The military situation was positive: Carranza had installed himself in Veracruz and was attempting to gather reinforcements; however, Pablo González’s army was disintegrating during its retreat. It seems that the meeting ended with an agreement to carry out a joint pincer movement by Zapatistas and Villistas on the city of Puebla. Villa would move on Veracruz from Apizaco.

Tensions would surface that same day as the three armies met in the capital. Gen. García Aragón’s family members appeared at police headquarters to denounce “a force of Zapatistas who had appeared at his residence.” Vito Alessio dispatched a group of officers to find out what was happening, and they reported back to him that the general was being held in one of the San Lázaro barracks by orders of Gen. Zapata. He, in turn, informed the president who told him to leave the matter in his hands. Later, Villa reported that the Zapatistas “threw him out” after an extremely brief council of war in the San Lázaro marksmanship school.

Eulalio Gutiérrez provided a more malicious version of events after the fact in which he stated that Gen. Guillermo García Aragón, the vice president of the Convention, “was arrested by Gen. Villa’s forces acting on instructions from Gen. Zapata, who had personal problems with García Aragón [in fact, they were not so personal]. As soon as I learned of this, I ordered Gen. Villa to release him, and Villa then offered to comply with my order. However, a few hours later, he handed the prisoner over to Gen. Zapata, who ordered him to be executed.” Octavio Paz Solórzano unwound the story when he stated that events were really much simpler and had to do with a conflict between Zapatistas and renegade Zapatistas, and that “Zapata did not ask Villa to do it for the simple reason that García Aragón was not a Villista.”

That night, Vito Alessio received a message from Pancho Villa asking for ten automobiles at 11:30 p.m. With police? No, only with drivers. Vito thought that the request might be an attempt to rescue García Aragón. But it turned out to be about a “round up” of children.

When they met up, Pancho told him that the previous night he had walked through the city center’s streets, and it broke his heart to see the multitude of nearly naked children sleeping under newspapers. It was December and it was cold. “I also suffered as a child.”

The police chief and Villa then drove around the center and began to pick up abandoned children, many of whom had been orphaned by the war. Some of the kids fled and were chased after by the Dorados while others approached them. They took them back to the station where Villa gave each of them a denim suit and a blanket and personally gave each of them two big sandwiches. Many of the children looked at Villa suspiciously. That night, they were put on a train for Chihuahua. One of the kids who had been rounded up and placed on the train was especially precocious, he said that Carranza had taken the horses and Villa was drafting the kids.

Pancho had sent Luz Corral a telegram some hours earlier telling her to mobilize the officers and the wealthy in Chihuahua, and to get money from them, in order to furnish the School of Arts and Trade and set it up as a boarding school for the kids he was sending.

Not all the kids remained in the school, several of them escaped by jumping the fence. They must have missed Mexico City and their rough and ready freedom. Some months later, the municipal president of Ciudad Juárez received a telegram informing him that several students from the School of Arts and Trade had escaped, giving their names as Andrés, Abdón, Moisés, and Eulogio, all between the ages of twelve and fourteen, and dressed in blue denim uniforms. He was asked to return them to the school if they were found.

Tuesday, December 8 was dedicated to Francisco Madero. At ten o’clock in the morning, bands began playing in Plateros and Isabel la Católica streets. Villa arrived, climbed a ladder, and showed off a plaque to the assembled crowd. And with no further ado, while the band played the national anthem, Villa hung up the sign, baptizing Plateros and San Francisco streets along their whole length as Francisco I. Madero Avenue. There are a series of photos that show Villa perched on the ladder in a sweater and his pith helmet, hanging up the sign with his pistol sticking out of its holster. Just below Madero’s name, a small sign warned, very much in the style of the Division of the North, that anyone who removed the plaque would be “immediately shot.” The signs had been previously posted by the Carrancistas, but the Zapatistas had taken them down. This time, they would have to be respected.

A second homage was celebrated at the Panteón Frances, a demonstration of pain and loss in front of Madero’s tomb. Villa arrived in his pith helmet and waved to everyone assembled at the cemetery’s gate before removing his hat. With Salvador Toscano filming, it was clear Villa didn’t know what to do with his hands. He had learned to stay still while photos were taken, but he didn’t know how to pose for a film.

Luz had knitted the thick, olive green sweater that Villa wore on this day. It was designed to fend off the Chihuahuan cold and the chill from Madero’s death. Among the public was Sara Pérez (Madero’s widow), Felipe Ángeles, José Isabel Robles, Raúl Madero, and Dionisio Triana, all wearing flower wreaths.

Villa addressed the crowd, “Here in this place, I swear that I will fight to the last for these ideals, that my sword [What sword? Another victim to the rhetoric of the time from which not even Villa could save himself] has always belonged, it belongs today, and will always belong to the people. Words escape me.” He jumped down from the ladder with large tears in his eyes. One of Madero’s brothers tried to hand him a handkerchief, but Villa pulled out his own, almost as big as a sheet. The camera caught Villa sobbing and when it shifted suddenly to Rodolfo Fierro, it found him overcome with emotion, holding a bouquet of flowers, needless to say, a very unusual image. After a time, Miguel Silva stepped up to speak.

When the theaters premiered El Norte y el Sur unidos, they saw Villistas and Zapatistas shaking hands on the screen. That’s how things were going when the story of the “French cashier” erupted. Villa was staying at the San Francis Hotel near the Caballito and the Division of the North’s offices, which were on 76 Liverpool Street. At sunrise, he would walk from one site to the other and stop for breakfast at the Palacio hotel. One morning, he made a pass at the waitress—she later showed off a short, hand-written note from Villa—who, frightened by the northerners’ reputation, didn’t show up to work the next day. Villa asked the owner, a French woman with the last name of Fares, about her. Fares, without knowing who he was, began mocking him and told him that the cashier was “well-guarded” with a price tag that not just anyone could afford. Puente adds that the owner, besides playing matchmaker, refused to accept Villa’s revolutionary currency.

Villa got so angry that he ordered his aid to detain the owner, the forty-year-old French woman and bring her to the Liverpool offices. Celia Herrera, who tends to add the most extreme melodrama to any story, renamed the hotel The Imperial, the waitress became a “young French cashier, the wife of the hotel’s manager,” who fled to her room when Villa called for her, pistol in hand, climbing the stairs himself to kidnap her from her room. René Marín added still more to the tale, claiming that Villa “sexually assaulted the French girl.” Vito Alessio, who investigated the story as chief of police, focused on another dimension of the story, “Villa abducted an old French matchmaker who tried to extract a large amount of money from him in exchange for handing over an attractive cashier.”

The news circulated through an atmosphere already prone to rumor and Villa was accused of having “kidnapped a young French woman.” The scandal caught on and produced a diplomatic note from the French delegation asking the president about the status of their countrywoman. Villa released the French owner and, in order to make amends, offered to buy the hotel in exchange for her leaving Mexico. Some weeks later, Aguirre Benavides, who was responsible for bringing the matter to a conclusion, discovered that the building the woman was selling was not, in fact, hers. The affair ended there, dropped from the public eye and was forgotten.

However, the story of the French woman would have an unexpected coda. Lt. Col. David G. Berlanga, a twenty-eight-year-old high school teacher born in Coahuila who represented the governor of Aguascalientes in the Convention, declared on December 7 in one of the Convention’s ongoing sessions that “Villa has been, is, and will always be a bandit.” It was not the first time that Berlanga had harshly criticized Villa. During the initial meetings of the Convention, his tone had been particularly heated. That same night in December, he left the Convention to dine at the Sylvain restaurant on 16 de Septiembre Street. Some of Villa’s aides were eating in the same place and when they were presented with the bill, they offered an IOU for the food and drink. The waiter consulted with Berlanga, a regular, who gave Villa’s aides an earful, telling them that the Division of the North was made up of a bunch of highway robbers and bandits. He paid their bill out of his own pocket and kept the IOU as proof. From here on, the versions of what happened next differ. Some say that the Villa’s men took the story to him, and he ordered Fierro to find García Berlanga and shoot him. Others insist that Fierro himself took the initiative, behind Villa’s back, to go to the restaurant the next day and detain García Berlanga and bring him to the San Cosme barracks, from where Fierro took him to the Dolores cemetery and had him shot.

Martín Guzmán related that Rodolfo Fierro later arrived at the Secretary of War’s offices and requested a private conversation in which he confessed, “I just killed David Berlanga . . . and believe me, I’m sorry about it. [ . . .] Under orders from the chief.” He was remorseful, not for having killed him, but for the courage that García Berlanga had demonstrated when he was put up against the wall. He had asked for a smoke, and the ash from the cigar never fell to the ground because he didn’t tremble. Ana María, his sister, initiated an investigation in various military headquarters in Mexico City, demanding that, at the least, she be allowed to recover the cadaver, which would not turn up in the Dolores cemetery until January.

The encounter in Mexico City of so many military strongmen, whose accumulated quarrels from the past had never been settled, was bound to produce a string of confrontations. Rumors continued to make the rounds that Gen. Juan Banderas wanted to liquidate the Minister of Education Vasconcelos. El Agachado, as Banderas was known, kept on telling anyone who would listen that he had paid Vasconcelos to defend him but that he had not done so. Vito Alessio, in his post as chief of police, asked Villa to intercede in the matter, but el Agachado answered to the Zapatistas and the most that Villa—who said that Banderas was a bastard who follows anyone who makes him an offer—could do was to provide Vasconcelos with Dorados bodyguards. Curiously, Vito’s brother, Miguel Alessio, told the story in reverse, remembering that “Vasconcelos was hounded and chased after by the Villismo’s main leaders.” The confrontation would take on a different form.

Around noon on December 9, Gen. Garay from Buelna’s forces stopped off at the Cosmos Hotel in San Juan de Letrán, where Banderas and his officers had taken up residence, firing a shot at el Agachado in the lobby. Banderas’ men returned fire and Garay fell dead. The shoot-out continued into the street. Vito Alessio appeared in the middle of the firefight and managed “with great difficulty” to end it, however, not before several peaceful passersby were killed. He arrested Banderas, whom he found wounded in his room, who told him that everything had started a few hours prior when he insulted Buelna in the entrance to the hotel, accusing him of being responsible for his arrest by Madero in 1911. Buelna had been unarmed when he (el Agachado) insulted him, and nonetheless, tried to attack him, but was stopped by el Agachado’s men. Back in his room, Buelna recounted the tale to some of his compañeros. Sometime later, Garay, Buelna’s second-in-command, who was very angry, took the elevator down and saw Banderas on the stairs. With only one shout to warn him, he drew his revolver and fired off several shots, but missed. El Agachado, crouching for cover, responded to the volley, shooting Garay dead. For several days, Buelna searched for Banderas throughout Mexico City until Villa ordered him to deploy his forces towards Nayarit and Sinaloa—at the same time taking the opportunity to get Fierro out of the city, sending him to Jalisco.

Rosa Helia Villa has suggested that, at that time, Villa carried on a relationship with the most famous stage actress in Mexico, María Conesa. Yet, it seems that Villa failed in the attempt. Fuentes Mares explained that Conesa sang a risqué song called “Las Percheleras” containing a line that went, “The knife that goes in and out.” While singing, María would come down from the stage accompanied by several guitarists and, knife in hand, slice ties and cut buttons off audience members’ shirts. On one occasion, she did this to Pancho who was attending the show. It seems that, according to Fuentes Mares’ version, Pancho fell in love with the star at first sight and tried to win her over, but María was out of reach. She remembered her husband “Manuel advised me, agree to see him, but don’t leave your dressing room.” Pancho greeted her with “great courtesy, keeping to himself [. . .]. As the visits became more and more frequent, his looks more audacious, and his voice more affectionate, I decided to flee. I hid outside the capital for more than a week.”

“Brothers of the race.” When did Villa come up with the phrase? To what little bird or revolutionary orator or member of his entourage do we owe it? Katz claimed that he used it while speaking from a balcony in Chihuahua in 1913, but the author has not been able to confirm that. At any rate, the fact is that in 1915 he used the phrase often in reference to the plebes, the plebes like him. In the middle of December 1914, while celebrating the capture of Guadalajara by the Convencionista Medina, Villa spoke from the National Palace’s balcony using the phrase. The people gathered at the sound of the bells and demanded that Villa and Zapata come out on the balcony and that Pancho speak. Many of the most important leaders joined in.

What is clear is that in his very brief and otherwise well-received speech, he mispronounced the word “defeat” (redotar for derrotar) and defended himself against the reactionaries’ accusations, which were bothering him more and more. That same day, Maclovio Herrera published a manifesto in Veracruz entitled “Villa, Behold the Enemy” in which he reviewed his time as a bandit riding with Doroteo. He wrote that Villa had had more wives than a sultan and that, if he were to triumph, he would turn the nation into one enormous hunting ground.

In order for Pancho to be heard, they had to signal to the bell ringers in the cathedral, who were going at it with great gusto, to be quiet. He spoke in a clear, high-pitched tone. Nellie Campobello said that he had a “metallic voice that carried well. His shouts were strong and clear, even and vibrant. His voice could be heard over great distances. His lungs seemed to be made of iron.”

And although everything appeared to be gliding along, the internal tensions among the Convencionistas were growing. The deaths of García Aragón, García Berlanga, and Garay made Eulalio Gutiérrez’s government feel that the situation was slipping out of its hands. Miguel Alessio recalled that the Minister of War, José Isabel Robles, met with Villa to tell him “Go and beat the enemy.” Getting Villa out of Mexico City was part of a deal he had struck in the council of ministers.

The same day as the shoot-out in San Juan de Letrán, December 9, Zapata departed Mexico City en route to Puebla, which he occupied on December 15. The backup which was supposed to have arrived by train never appeared, the artillery arrived late and had to be transported by mule. The atmosphere was ripe with conspiracies and more than one actor attempted to poison relations between Villa and Zapata. Pancho explained: “I didn’t have a single day without hearing denunciations and accusations in which my own friends were accessories; they constantly wanted to cause frictions with the Zapatistas.” Miguel Alessio maintained that “Villa loved Mexico City. He didn’t want to leave. He was intoxicated with its pleasures.” But the truth was exactly the opposite. Villa did not like Mexico City and was sick of the gossip, slander, and conflicts; he was eager to leave and put an end to Carrancismo. If something was stopping him it was that the original plan of marching on Veracruz did not appeal to him because it left his back, and his base in the North, exposed.

The Carrancistas had earned a very bad reputation during their time in Mexico City. The plebes rearranged the letters in Álvaro Obregón to spell out “vengo a robarlo” (“I come to rob it”) and they called, in jest, the Carrancistas the “heroes of the mansions” because they had happily expropriated the Huertistas’ mansions for themselves. However, their reputation paled in comparison to the Villistas’ reputation, especially that of Tomás Urbina. Martín Luis Guzmán affirmed that: “Compadre Urbina not only settled accounts with the rich, but he also carried [the thefts] out with great attention to detail, to a more perfect degree than any of the other generals who emulated him in those days. His knack for choosing victims was spot on. His maneuvers were silent, all but infallible. He did not miss a trick.” Martín, who had not joined the Villista movement in Chihuahua, was unaware of the Division of the North’s practice of forced loans. One kidnapping raised a particular racket in Mexico City, that of Jesusito García and his nephew Francisco Salinas, both rich Zacatecans. The kidnappers aimed to force them to hand over a forced loan, which Nicolás Fernández in his account, magnified to the implausible sum of $30 million pesos. Vasconcelos transformed that one abduction into a wave of kidnappings, claiming that “Night after night, the Villistas are plaguing well-to-do neighbors, shooting dozens of unknown peaceful civilians, and it is well known that every morning, in Villa’s own car, his favorites, the Pancitas—this last group was a complete fabrication by Vasconcelos, most likely based on Baca Valles—Fierro, and others divided up the rings and watches of those who had been shot the previous night.” This staging seems delirious.

The consolidation of this alarmist version of events hardened over the years. Ramírez Plancarte echoed it and Celia Herrera drove herself crazy delighting in it, “At the Tacuba station [. . .] defenseless civilians of all classes were brought during the night and were murdered beside the train.” Knight lent this tale academic support: “While public relations wavered and respectable Villistas were not heeded, Villa’s old military compadres imposed their rule: a wild, dithyrambic revelry. Rape, shootings, and murder distinguished their occupation of Mexico City.” All that was left to do was to repeat this judgment and cite it in footnotes.

Social gatherings took place in Lanz Duret’s house in which Justo Sierra’s widow took part. Miguel Alessio, who frequently attended them, recalled that the frightening tales were taken very seriously. The central figure in the witches’ tales was Rodolfo Fierro, of whom he left a description: “Tall with brown skin. Set under thin eyebrows, his wide-open eyes fired terrifying looks. His straight hair fell in black locks down over his forehead. A large mouth. His wet lips revealed shining white teeth, like those of a leopard constantly stalking its prey. The most terrifying man in the Revolution.” Vasconcelos would later add his own rant about Fierro based on his first impressions in Mexico City, combining a demonization of Villismo and pathetic anti-Indigenous bigotry: “The footwear from the North and the khaki uniforms that the Carrancistas brought in from Texas saved the republic from once again being dressed in the Aztecs’ crude blankets. And Fierro’s savagery saved us from the return of the Indigenous because, on his own account and according to his own preference, night after night, he shot ten or twenty Indigenous Zapatista colonels.”

On December 10, Vito Alessio Robles accompanied Felipe Ángeles to an emergency meeting with Villa at 76 Liverpool Street (Ángel del Caso’s house). Villa, who had been busy securing fuel to move the Division of the North’s trains and the exchange of Carrancista currency for Chihuahua currency, showed them some telegrams he had received from Emilio Madero from Torreón, stating that the Carrancistas had arrived in San Pedro de las Colonias and were threatening the Lagunera region, (an area featuring a series of lakes and waterways) which was relatively unprotected.

Villa then made a critical decision. He ordered Ángeles to send his forces, to which he added an additional two brigades, to Torreón, which “is my base of operations and supplies” and to advance on Saltillo and Monterrey. Ángeles did not agree, telling him it was necessary to strike at the enemy’s head, towards Veracruz, against Carranza. He argued that Raúl Madero’s forces were sufficient to contain any threat in the Laguna region. Villa reiterated the order: Move to the North. The Zapatistas would strike at Obregón, Alvarado, and Coss in Puebla. The disagreement continued. Ángeles once again proposed that the main offensive force should target Veracruz. However, Villa was absolutely convinced, the priority was to eradicate any kind of threat to the northern territories, his natural base. Ángeles submitted, almost immediately returning to the Morales hacienda, and ordering the commencement of the artillery’s departure.

One day later, December 11, the trains began leaving Buenavista. Irapuato was designated as a concentration point for the Villista brigades. Urbina would move towards San Luis Potosí, through Huasteca, and arrive in Tampico to cut of Carranza’s oil supply. Felipe Ángeles would meet up with Raúl Madero in La Laguna and from there he would march to Monterrey and Coahuila. Villa himself would march from Irapuato to Guadalajara. When they had launched their mobilization towards the center of the republic, their barracks in the north had filled up with volunteers who wanted to join in with Villa and his magnetism. If they had had enough arms, they could have raised an army of 50,000 men.

While Villa reorganized his column in Irapuato, the disappearance of Paulino Martínez was creating enormous tensions in Mexico City. Paulino was one of the most important Zapatista delegates in the Convention, an opposition journalist who broke with Madero and then joined with Vásquez Gómez and Orozco, only to break with them during the Huerta coup to join the Zapatistas.

On Sunday, December 13, Martínez went to the Ideal theater with his daughters. When they were returning, a messenger brought him a card from the Minister of War, José Isabel Robles, asking him to meet with him immediately. The messenger was recognized as Robles’s driver, someone who was not easily mixed up because his face was pockmarked, “like grains of gunpowder.”

After he failed to return from his appointment, the family contacted Eufemio Zapata, and he then contacted Robles who denied having sent an invitation to Martínez. The following morning, the president and Gen. Gutiérrez informed Paulino’s son that his father “had been assassinated, beaten to death, in a town near Mexico City and that the body had been incinerated.” However, despite having so much information about the murder, he made no mention of who was responsible for the crime. A huge wave of anger exploded among the Zapatistas. Gen. Palafox threatened to arrest the president. Some months later, Martínez’s wife was told that a “group of ranchers” (whoever they might have been) had kidnapped him, took him to Jalapa and then to Teocelo, where they shot him. Octavio Paz would later say that Paulino’s assassin was Gen. Joaquín de la Peña, a character that the author has not been able to locate in the archives.

However, various stories attempted to implicate Villa in the assassination. It was said that “some spiteful person put a copy of La Voz de Juárez of February 21, 1913, in the centaur’s hands (as Villa was known) [. . .] (which contained a note from Paulino in which he protested the possible release of Madero and Pino Suárez) [. . .] because it would constitute a serious danger for the reestablishment of peace and called on Félix Díaz’s patriotism to keep them in prison.” Villa became enraged upon reading it and ordered Paulino’s assassination. Luis Aguirre Benavides, in a different version created after his split with Villa, stated that it had all been due to Isabel Robles complaining about the Zapatistas’ excesses in Mexico City and the subsequent serious situation that arose at the Convention. Villa ordered Fierro to fix it, who did so in the only way he knew how. Fierro got in the car and went to the San Cosme barracks. Vasconcelos alleged that “Fierro personally confessed to Eulalio that he had shot the illustrious old man . . . because he felt like it.”

However, the story has holes in it. At the time, relations between Villa and the Zapatistas were prudent and fraternal, marked by mutual respect, even deferential. Paulino was not a poster boy for Zapatista excesses, far from it. Not that it mattered to the storytellers, but Rodolfo Fierro was not in Mexico City at the time and never even spoke to Eulalio, much less confessed to him. Rather, it seems that the assassination of Paulino was intended to drive a wedge between the Division of the North and the Zapatistas. In fact, Zapata wrote to Villa along those lines a couple of days later, remarking that “Our enemies are working very actively to divide the North and the South [. . .] which obliges me to recommend that you take the greatest care about your own circumstances.”

That was the last link in a chain of bloody events in which History—stories created after the fact that were elaborated in great and fantastic detail—affirmed the existence of a plot by Villa and Zapata to rid themselves of various people.

How was such an attractive slander constructed? Elías Torres wrote an article titled “Tragic Exchange” in which he narrated in fine detail a supposedly secret pact that was made after the meal in Xochimilco on December 3. He asserted that Villa saw Marcelo Caraveo and Benjamín Argumedo—neither of whom were in Mexico City, nor at the banquet, according to Octavio Paz Solórzano who later polemicized against this version of events—and told Zapata to turn them over to him, a request which Zapata refused. During their subsequent meal in the National Palace, Zapata discovered the two had betrayed him and had gone over to join Figueroa’s troops but were now working as assistants to Gen. Guillermo García Aragón. At the same time, Villa came across Paulino Martínez. At the end of the meal, Zapata suggested they exchange the two and have them executed. The story is as inconsistent as it is absurd. García Aragón was no Villista, and Villa had been together with Martínez in Guadalupe. Besides, Paulino himself was one of the presenters at the meal in Xochimilco where he had spoken favorably of Villa.

In one way or the other, this version of events hardened. González Ramírez referred to the “informal summit” of the alliance of Xochimilco, which included the execution by firing squad of Col. Manuel Manzanera (which, had taken place long ago), later insisting that Villa and Zapata traded García Aragón and Paulino Martínez: “It was as public as it was infamous that [. . .] they agreed to exchange prisoners, who were then shot.” Quirk repeats the same idea, granting it academic credibility, “As casually as if they were playing heads or tails, the two chiefs picked out their human victims.” Ramírez Plancarte seconded this version. Miguel Alessio (Obregón’s future biographer) added, “Villa didn’t hesitate to give free rein to the insults and ordered the killing of [. . .] the journalist Paulino Martínez.” Among these stories, anything goes. Luciano Ramírez added that “With the arrival of thousands of soldiers from both the North and the South, a wave of lootings, murder, and outrages of all manner broke out in the capital of the republic during the first days of December.” Knight, basing himself on Cumberland and Canova, claimed that there were two hundred murders in Mexico City during this period. A review of the newspapers and the archive demonstrate the extent to which the figure has been exaggerated and proves the absurdity of the implication that these were political acts.

This is the critical moment when the black legend of Villa was constructed, during the years 1918–1919. A character as morally suspect as Nemesio García Naranjo, Huerta’s Secretary of Education, insisted: “Villa did not join the Revolution based on a dream, because beasts are incapable of dreaming [. . .]. Villa participated in the Revolution with no goal in mind for the Revolution itself, rather, he joined because only in a territory where all the dams had collapsed could his spirit unfold in wild and uncontrollable freedom.” Appelius would call him “the reincarnation of Huitzilopochtli” and Basilio Rojas the “terrifying presence.” Vera Estañol described him as “a backwards criminal character in both his physical and moral makeup, possessing a great magnetic power over the lower classes and the despicable elements,” and, in a variation on the theme, “a character steeped in natural-born delinquency, the example par excellence of backwardness.” Years later, Salvador Novo asserted that “The sinister figure of Villa can never be wiped from the memories of those who suffered under his heel,” continuing that “he was subterranean, an unseeing whip; he lacked the capacity to distinguish between those he mowed down in his path.” And Vasconcelos, in 1940, challenging those narrators of the Revolution who valued Villa’s role, argued that “more than a few writers suffering from a complex in which they are complicit with criminality have glorified Villa.” B. Traven, in one account, invented a story according to which Villa ate lunch in Torreón in 1915 with the heads of his enemies hanging from the front of his balcony because “he couldn’t work up an appetite unless such ornaments were right in front of him.” Nellie Campobello rightfully recorded that Villa’s “black legend extended to the most innocent gesture in his daily life.”

However, Pancho wasn’t only accused of all manner of outrage and bloodthirstiness in Mexico City—and it must be said that García Berlanga’s killing, and the matter of the French cashier gave his enemies sticks with which to beat him—he was also the target of a fierce propaganda attack from the Carrancistas, particularly the factions around Villarreal and Obregón who both justified their betrayal of the Convention with the “reactionary Villa” argument.

On December 16, the daily newspaper La Convención was first published in Mexico City, resuming its production from Aguascalientes, and now edited by Heriberto Frías. The next day, the paper chronicled Villa’s entry into Guadalajara (and Diéguez’s flight), greeted by confetti and given a warm reception by the oligarchy and clergy. “The beautiful women waved their handkerchiefs [. . .] the oligarchy’s dignitaries and speculators reverently knelt before the leader.”

Some days before, from Ocotlán, Villa had declared freedom of worship. Acting pragmatically, he allowed the reopening of churches in Jalisco, “The temples belong to you, you may open them when you wish,” which his Jacobite rival, the Carrancista Diéguez, had shuttered. Thus, in the eyes of the clergy, Villa became the “savior of religion.”

Faced with Diéguez and Murguía’s actions, Villa’s clerical policy was aimed at avoiding excesses. Indeed, Knight correctly pointed out that the agnostic Ángeles opened the churches in Monterrey that had been closed by Villarreal. Puente described Villa’s attitude as follows: “He was happy to combat fanaticism, but he didn’t want a people without religion. When one of the governors told him that he had ordered the confessionals burnt and had decreed the prohibition of hearing confession, he [Villa] counseled him “not to mess with the old women.” Catholicism was, for him, a part of his country; “whoever doesn’t practice it doesn’t understand it.” Did Villa really not want a country without religion? Better to say, amending Puente’s assessment, that he didn’t want religion to be a source of conflict. He didn’t much like religious ceremonies and, in 1913, used an iron fist against a clergy which he saw as collaborating with Huerta’s dictatorship and the latifundia. Then, he had expelled the Spanish monks and priests from Chihuahua, ordered the priests in Saltillo to be transported to the border, and after the capture of Zacatecas, he allowed the looting of the bishop’s palace, filled a wagon with priests and demanded a ransom for their return. Yet it was one thing to put the clergy in its place, as he did with the priest in Satevó, and quite another to close the churches to those who wanted to attend them.

The Carrancista left, in the break at the end of 1914, not only grew fearful of Villa’s “perverse instincts,” but honestly believed—not simply inventing the issue as a propagandistic device—that Villa had fallen into the hands of the reactionaries. They thought that he had no social program whatsoever, thus, seeing him as far removed from the “true revolution” that the Jacobin wing of the Carrancistas hoped to carry out, despite Carranza’s opposition to their own ideas. This idea of the Villistas being reactionaries ring out in every stanza of a song called “Las Mañanitas de la División del Norte” by Enrique C. Villaseñor: “These are the generals/ with whom the bandit Villa/ cheers up the clerics” or “When the Yaquis’ drums begin/ the reactionary hoards/ forget their big words/ their guns and their rosaries.” Villarreal wrote to Carrera Torres, claiming that in Chihuahua, Villa had carried out an agrarian reform in which he had distributed land and mines to his friends and family members.

Heriberto Frías reprinted agrarian measures and laws from Chihuahua in the pages of La Convención to demonstrate the accusations were false. But it would be Pancho’s day-to-day actions with respect to the oligarchs that would demonstrate his true character. Villa formed a local government in Jalisco in which he appointed Mariano Azuela (the future novelist) as Secretary of Education, a figure who could in no way be accused of being tainted with clericalism and called for an assembly of all guerrillas in the city. He dissolved all private militias—he didn’t want to risk any secret white guards—and then took a machete to the town’s wealthy, demanding a forced loan of $1 million pesos, generating a powerful unease among them. Dr. Ramón Puente was placed in charge of despoiling the Jalisco oligarchy, provoking protests among the largest hacendados and merchants. And in order to put a dead stop to these, the government ordered two high-ranking Huertista officers shot along with three hacendado brothers named Pérez Rubia. Villa, in turn, during a banquet organized in his honor fired a shot at Joaquín Cuesta, the brother of the town of La Barca’s old tyrant and the brother of Porfirio Díaz’s godson.

Yet it seems that Pancho Villa’s romantic pursuits bothered Jalisco’s conservative social elites even more. Pancho met Margarita Sandoval Núñez, a native of La Barca, in Guadalajara while she was accompanying her mother to claim her inheritance and soon began a public romance with her. Margarita was by his side during this period of the campaign, later going to the North and giving birth to his daughter Alicia.

The success of the Jalisco campaign, in which Diéguez avoided a definitive confrontation, was overshadowed by Triana’s betrayal in Lagos de Moreno. Gen. Martín Triana went over to the Carrancistas, but this wasn’t itself a very serious matter, in fact, Villa had deprecated him since the Battle of Torreón. However, during his escape, he shot Gen. Faustino Borunda twice in the back, and Triana’s troops shot recently-promoted Gen. André U. Vargas in the neck, killing him. That same night, Villa appeared in Lagos and arranged for a special train to carry the cadavers of these faithful friends to Chihuahua.