forty-seven

portraits at the halfway point

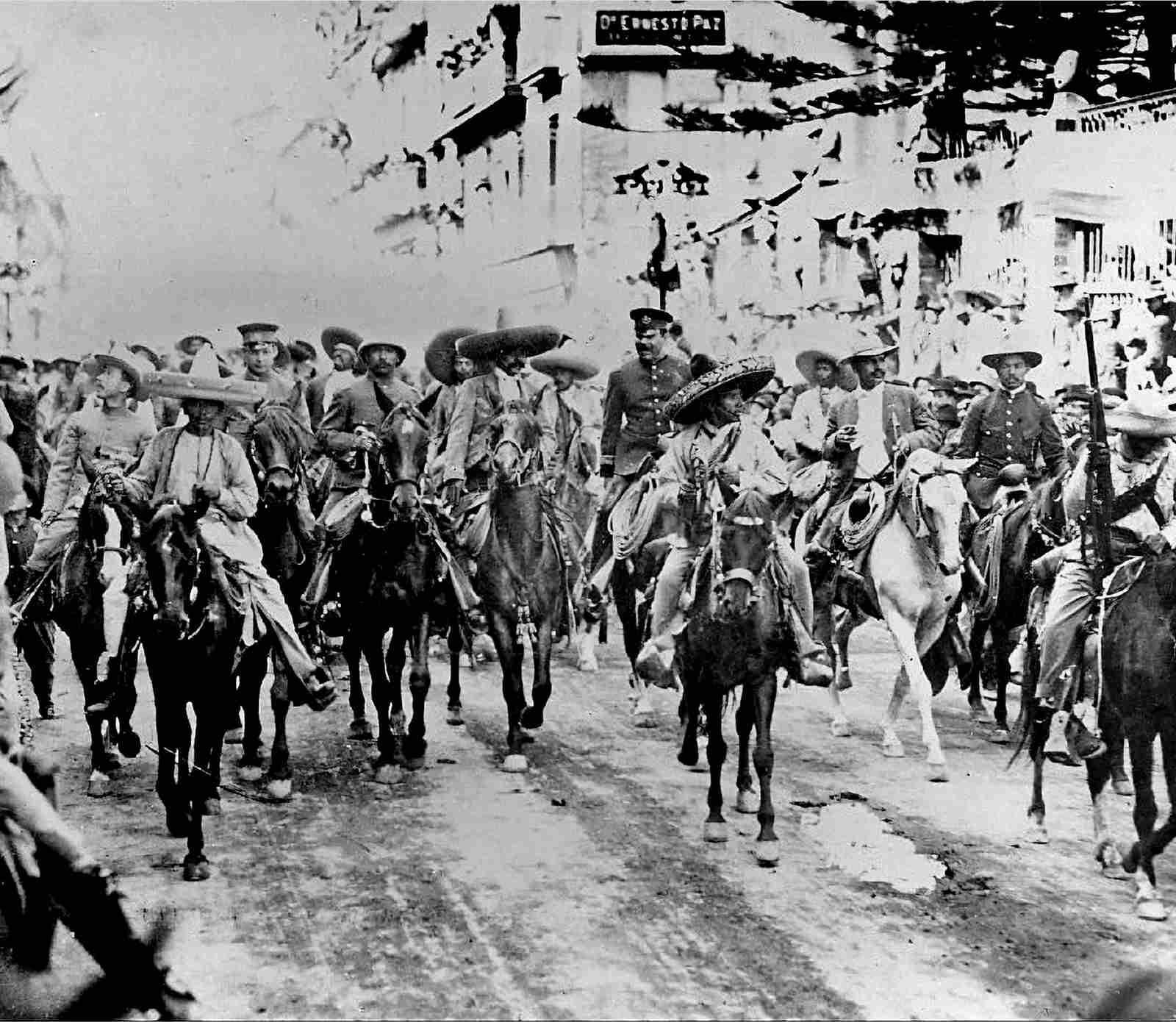

Pancho Villa is in black and white. For the narrator’s generation, at best, the Casasola’s archive showed us Villa in sepia. And we still can’t get over reading that he had a reddish-brown mustache—Puente says, “his reddish mustache drooped down.”

Rubén Osorio, in a series of interviews with survivors of Villismo, recovered some charming descriptions. For example, Concepción García said that Villa was “tall, very stocky, clear-eyed, with light, chili-colored skin. Neither fair nor dark, but goldish.” Domitilo Mendoza insisted on his own description, “He had a saffron-colored light complexion, like those from Durango.” Some called him the güero de rancho (fair-haired rancher). Dr. Monteverde added his own twist, maintaining that Spartacus was also a fair-haired rancher, like all the Thracians.

Capt. Chávez described him as, “Taller than average, robust, with burnt-reddish skin and curly hair . . . with a wide forehead, very bright, a short neck, powerful jaws.” And Sgt. Momitilo Mendoza added, “He was paunchy, thick, not very tall, and plump-cheeked [. . .]. He always kept his mouth open, like his jaw was dropping. He hobbled a lot because he was bow-legged. And he always wore a hard look and mistrusted half the world.”

The photographer and journalist Alexander Powell, who didn’t like Villa much, offered this: “he is stocky built and of medium height [. . .] with the chest and shoulders of a prizefighter and the most perfect bullet-shaped head I have ever seen [. . .]. His head was covered with black hair as crisp and curly as that of a negro [. . .] a small black mustache serves to mask a mouth that is cruel even when it smiles.”

Ramón Puente asserted that “This Villa character is dashing, without ceasing to be vulgar, his head is round, his forehead is broad, and his brown hair is curly, but his mouth is rough, his lips and teeth are somewhat coarse and bulging, and his teeth are stained ocher yellow from ferruginous water which is very common in Durango.” Encarnación Brondo also remarked about his yellowed teeth owing to drinking water from puddles during his bandit days.

However, what almost everyone who described him focused on were his eyes. Nellie Campobello said, “When Villa was in front of you, all you could see was his eyes, they were magnetic.” And “his whole being was contained in his two yellowish eyes, semi-brown, they changed color at all hours of the day.” Federico Cervantes completed the picture, “His brown eyes had a rare expression: big and simple, dominating and defiant, almost savage when he was irritated; then, all bloodshot, he would open them extremely wide in a threatening way; on the other hand, accustomed to withstanding the intense sunlight and scrutinizing the horizon even at night, or reading the attitude or thoughts on the faces of others, or when he spoke affably or laughed, he almost closed them, scrunching up his brow.” Puente spoke of his “magnetic gaze” and Capt. Chávez remarked that “his eyes were small, but cast a ferocious look.” With regard to his brown eyes, Powell wrote, “they are not really eyes, but awls that seem to bury themselves deep in your soul.”

Puente added some essential characteristics to this portrait, “He had an undeniable gift with people [. . .] and his words were persuasive. He would win over, as he used to say, anyone he wanted, and he always displayed a vivid imagination in his stories.” The novelist Rafael F. Muñoz offered a description with which this author does not agree, but presents here in the interest of plurality, “Villa was a tremendously illogical person [. . .] faced with two identical situations, he would act differently each time.” Puente also referred to an odd part of Villa’s personality, “He had strange premonitions. It would be difficult to estimate to what extent these states of consciousness hurt or irritated him.”

Enrique Pérez Rul, also known as Juvenal, Villa’s secretary after Luis Aguirre’s departure, left behind a picture of his habits and likes that was published after he stopped working for him. He liked to dance, sing “little sonnets” from Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Jalisco, and “belt out a tune.” Soledad Armendáriz confirmed this point, “He didn’t have a very good voice, but he liked to sing.”

“He sleeps very soundly whenever he wants.”

“Any drunk that crosses his path has a rough time.”

“Suspicious and a smooth talker.”

“Villa hates stingy people.”

“He hates discipline.”

And when it came to Mexican history, “He venerates Hidalgo,” is familiar with Morelos, and knows all about Juárez and his clash with the clergy.

But of all the portraits, perhaps the best is from Ramón Puente, thanks to his particular skill in finding just the right words in a universe populated with platitudes. “Courage to the point of recklessness; generosity to the point of waste; hatred to the point of blindness; fury to the point of criminality; love to the point of tenderness; cruelty to the point of barbarity; and all of this in Villa in a single day, in a single hour, a single moment for every moment of his life.”