forty-eight

the sonoran adventure

Villa, in a letter sent after the fact to Zapata, explained his intentions in the wake of the perilous adventure that he had dreamt up: We’ll reconcentrate our forces in Chihuahua, invade Sonora and rally the region’s combatants, then advance on “Sinaloa, Tepic, Jalisco, and Michoacán until we have the pleasure of meeting up with you.” It was a crazy plan, one that would disrupt the simplistic Obregonista geography, but that would also leave Villa’s back to an invasion by Obregón’s columns into the heart of Villismo in Chihuahua. Yet, Villa felt only by taking a great risk could the balance of forces be evened up after the last months’ defeats had tilted the scales dangerously in the Carrancistas’ direction.

He was counting on the fact that the new Sonoran governor, Carlos Randall, had Nogales under control and that Urbalejo controlled the south, that is, Hermosillo and Guaymas. Francisco Urbalejo was a reliable character, a Yaqui born in 1880 who had been a Federale—a persecutor of his fellow Yaquis—but who had returned to his roots and joined Sanjinés troops and participated in the capture of Ciudad Juárez. Villa was unaware that Maytorena, before departing, had given Urbalejo and José María Acosta instructions to help him in Sonora. However, if Villa wanted them to leave the state’s territory, they should make up an excuse to not do so, up to—and including—dispersing their forces.

The main objective was to defeat Plutarco Elías Calles and his 3,000 men in Agua Prieta and then begin an offensive towards the south. Julián Medina was harassing the Carrancistas in Sinaloa and Villa believed he could create a new column with Banderas, el Agachado, to conduct an incursion into the region; he also believed he could count on Buelna. Maybe the northwest axis would come together.

Around this time, Scott received a report from an American who had spoken with Villa and, after evaluating the situation, concluded that although the Division of the North was “very disorganized, it was in no sense destroyed.” It was true that the great war machine had not been broken, although it had been weakened by desertions and low morale, and Villa was facing delays due to economic shortages. Villista paper currency had collapsed in value, the best exchange rate going was on September 15, when it got five cents of a dollar per peso and although they were striking silver coins in the Division of the North’s mint, the quantity was insufficient. The problems were afflicting them on all sides. On September 25, Madinabeytia couldn’t run trains out of Durango for lack of coal. Villa had ordered the confiscation of the Asarco company of Chihuahua, but it proved impossible to get it working under duress. And they couldn’t count on Lázaro de la Garza who—though he was still involved in the Division’s operations and more or less maintained control over Villa’s munitions purchases in the United States, in particular one contract guaranteed by Rio Grande Valley Bank and Trust Co. of El Paso in which Lázaro had deposited $17,500 but had promised $1 million—was serving other masters. Without Villa’s knowledge, Lázaro—working through “García” or “Garza” in Los Angeles—was sounding out the possibility of buying arms for Obregón. Not only was he abandoning Villa, he was trying to join the other side.

Sometime later, in light of the fact that Carranza’s government had been recognized while there was an arms embargo on Villa, Lázaro sold cartridges he’d already bought for the Division of the North to J.P. Morgan who, in turn, sold them to the French army. De la Garza earned a commission of $24,000 for his troubles. After the operation, as Luz Corral put it, the agent, “taking advantage of this fortune [. . .], continued living in Los Angeles like a magnate.”

Shortly before the first contingents left for the Sonora campaign, Villa spent the night with some trusted compañeros removing a deposit of some two million cartridges from the Chihuahua governmental palace and burying them close to San Andrés. On September 23, trains carrying José San Ramón’s infantry set out for Casas Grandes. Each soldier was issued two blankets and a cover, a tarp, a bedroll, a uniform, a pair of shoes, and underwear. Provisions, as judged by the combatants, had greatly improved. It wasn’t like in Bajío, where food had been scarce. The Procurement Department of the Division of the North under Primitivo Uro was functioning like clockwork. The Division of the North’s medical services were also reorganized, and a lot of provisions were arriving from the United States. In the wake of the infantry, the first artillery convoys got underway. Villa was photographed by the US press while he was at the station reviewing his troops. He called many of the veterans by their names and recalled their hometowns. Both Puente and I. Muñoz associated the word “prodigious” with Villa’s memory. And it certainly was. Villa once said to his secretary Enrique Pérez Rul, “I have a memory as sharp as a blackbird.” The secretary had no doubts about Villa’s memory, but it did leave him wondering about blackbirds.

On October 6, a column of 6,000 men left Chihuahua under the command of Orestes Pereyra and Juan Banderas en route to Sinaloa. Villa gave them a sendoff. He believed these troops would close the Sinaloa attack’s pincer movement from the south. Buelna attempted to meet with Villa personally to find out his plans firsthand; and despite the fact that he had been ordered to remain in the south, he tried to do so again. On September 25, Villa had written to the governor of Durango, “If Buelna has not already left for here (Chihuahua), please tell him it is better he not come [. . .] because he might end up cut off from his troops [. . .] he should communicate by telegram with me.” Buelna ignored the suggestion and found Pancho in Chihuahua, where they met for several hours. Apparently, Pancho managed to convince him to sign up for this last push, but only apparently. As soon as Villa left Chihuahua, Buelna took a train for Juárez with his brother and retired from the struggle.

The southern border of Chihuahua was militarily covered. Their forces were thin, but Villa, rightfully, trusted in the Obregonistas’ sluggishness. Murguía, who occupied Torreón on September 28, did not move towards Durango until the middle of October.

Finally, on October 7, the command train started for Ciudad Juárez where Villa remained for four days. He received a detailed report from Juan N. Medina, who told him that Pablo Seáñez had shot to death Gen. Luna in a quarrel in a cabaret called El Gato Negro, a gambling house where they played roulette, redina (un upright kind of roulette), poker, baccarat, albures (a verbal game based on guessing cards), and a game called Siete y Medio, an Italian form of blackjack. Villa, who couldn’t afford to lose any more people, called Pablito Seáñez—whom they called Pico de oro (Golden Beak) because a bullet wound from Torreón had knocked out several teeth which he replaced with gold—to come to Casas Grandes.

Pancho Villa was depressed, claimed one journalist writing for the El Paso Morning Times—a daily which had been receiving a subsidy from the Villista government—however, he seemed lively when he responded to a request for an interview in Ciudad Juárez published on October 9, and reproduced a week later in Vida Nueva: “I am completely exhausted, the past month has been the most tiring of my life and my energies have reached their limit [. . .]. It’s possible that I have made many mistakes [. . .]. A year ago, it seemed as though victory was in our hands [. . .]. Yes, my forces are diminished. We don’t have the men or the money we used to. All those who made money from our side have fled because they can’t obtain any more profits.” Was he thinking of Lázaro de la Garza? Or Carothers? Of Sommerfeld? After making it very clear that he had not conducted any personal business in the shadow of power, he continued, “Although I am no angel, I thank God because I haven’t made any money while my fellow citizens are dying on the battlefield for the cause I represent.” And in response to the journalist’s assertion that Carranza’s government would soon be recognized, Villa replied, “I can’t believe it [. . .]. What will happen will happen.”

On October 12, he left for Casas Grandes, accompanied by Juan N. Medina, near the end of the rail line and the expedition’s last assembly point. Although some witnesses claim that “Villa’s presence in Casas Grandes seemed to galvanize the people,” Pancho was informed that two generals named Pállan and Navarrete from José E. Rodríguez’s cavalry brigade had deserted with 800 men the previous day.

That night while troops were gathering in Colonia Dublán to the north of Casas Grandes, a warehouse storing dynamite exploded, wounding a large number of men from the Second Villa Brigade. Was it an accident or sabotage? Pancho arrived soon after with his guard. The ambulances were overwhelmed by the dead and injured. Villa refused to leave until the scene had been completely cleared.

And this wasn’t the only problem. “Some generals,” whose names we don’t know, discussed how out of touch he was. The recent accumulated defeats affected them, and many could not understand Villa’s plan for the Sonora campaign, not to mention the demoralizing desertions. Villa, according to Puente, recalled:

There was an incident that demonstrated to me just how far the majority of my commanders had been corrupted. When I arrived in town, I was advised that some of my generals were meeting to discuss a plan to assassinate me. Playing like I was unaware, I turned up at this meeting and, after exchanging a few words, I said,

“Señores, I have no illusions about what I am worth, I know very well that my life is in your hands and if you believe that I am an obstacle, dispose of me as you will and kill me; but I assure you that if you take that step, we will be less sure of victory and of someday realizing the ideals we are after, and I don’t believe that you have so little dignity as to turn all these people over to Carranza.”

This surprise unsettled them and—not being sure of their troops, that they might riot if they placed this proposal before them—they all rushed to reassure me of their loyalty.

Before initiating the campaign, Villa was informed about the Obgregonista forces’ movements. Obregón had ordered Diéguez to sail from Mazatlán to Guaymas in the General Guerrero gunboat and from there to advance on Hermosillo, while Calles was to extend his zone of operations towards Nogales. Diéguez captured Guaymas from the Sonoran Villistas but remained shut up in Agua Prieta.

Villa issued orders that “no soldaderas” accompany the column. Medina was charged with the task, loading the women who had accompanied the combatants on a train which returned them to the Delicias station where they were to wait. The order was absolutely sensible because the passage to Sonora was dreadful, however, it caused a great commotion among the troops in general and in particular with José Rodríguez and his “enchanting and youthful” lover who refused to comply with the order and dressed up like a man to disobey it before she was discovered. Questions arose among the troops about whether the order applied to the high command. Villa ordered the young woman to be shot, although he later retracted the sentence and allowed her to remain in Casas Grandes.

Only Fierro and Robles’s brigades had not yet arrived. They had started out for the gathering spot on October 10, but had been detained in Villa Ahumada to collect food, blankets, rope, and medicine. It was very cold and Fierro, who had been drinking too much, was keeping warm with tequila. On October 13, to the east of Nueva Casas Grandes, Fierro arrived with the vanguard of his forces at Laguna de los Mormones, a man-made lake used for irrigation. Disregarding the clear path around the lake, and still drinking, he dug in his heels and insisted on riding through the middle of it even though the water was very high. Rafael F. Muñoz described Rodolfo that day, “A Texan hat turned up into a point in the front, like the railway workers wore them, those who laid the tracks. Dark face, completely shaved, straight, black hair that almost bristled; mouth like a bulldog, strong hands, an upright torso and muscled, bulky legs that gripped the side of his horse like an eagle’s talons.”

In the middle of the lake there was a drop-off eighteen meters wide and five meters deep, and the ponds in the area were half frozen. “This is the path for men who are men, riding horses who are horses,” they recalled Rodolfo Fierro saying. When he was crossing, his mare sank to the bottom and Fierro swam back laughing. The story goes that he asked his aide Manuel for another horse, a spare sorrel mare he had brought with him, and tried to cross in the same spot again. Col. Mantecón insisted that it was useless, that they could get around the lake in a few minutes. “Fierro said that he was already wet, and we were going to cross this way,” and he mounted his dark horse bareback. In short order, the horse began to tire because it couldn’t get any footing and then became stuck in the mud and Fierro, despite his compañeros’ warnings, paid no attention, saying that it was just a puddle. His last words were, “Why not, follow me.” When the mare reached the drop off, she lost her footing and did a somersault with Fierro dragged underneath. It was thought that the horses’ hooves knocked Fierro unconscious.

Later, others would say that the horse lost its footing and then dragged him to the bottom since he was carrying a large number of $20 gold pieces, known as “ox eyes,” under his cartridge belt and in canteens tied to his saddle. Rafael Muñoz transformed this into “kilos of gold.” The truth is that he was only wearing a cartridge belt that might have fit a few coins, the kind they called a “viper.”

Nothing floated to the top except his Texan hat. The men traveling with him jumped in to look for him, but found nothing. Mantecón headed out for Casas Grandes to inform Villa. Pancho received him in his train.

“I have news, my general, that Gen. Fierro has just died.”

“And where did the bullet hit him?”

“He didn’t die from a gunshot, he drowned.”

“Drowned. . . drowned from drinking?”

Around dusk, Villa arrived at the scene of Fierro’s death. Villa, with Martín López, circled around and around. Pancho, without speaking, looked at the large pond in silence as tears fell down his cheeks. He then said that anyone who pulled his body out could keep whatever he had on him. Villa didn’t sleep that night.

Five days later, after a group of Chinese men failed to recover his body—the story gets even more exotic—a Japanese diver managed to bring Fierro up. His spurs had been tangled in some roots. On October 20, his cadaver arrived in Juárez as rumors swirled about his death, including rumors implicating Villa. Among the belongings turned over to his widow was an eighteen-karat diamond ring. “Only ten,” said J.B. Vargas.

Soon after, Fierro’s brigade gathered beside a train where Villa sought and won approval to name José J. Valles commander. That same night they learned that Ángel Flores had been defeated in El Fuerte, Sinaloa, by Banderas’ column and that Pereyra was heading north. This meant that the Sonora campaign now depended on Villa.

Fierro’s death and the leak of the attempt to depose Villa stirred all sorts of talk in El Paso, the permanent amplifier of all events in Mexico, a city home to the most outrageous gossip. It was said that there was a complex plot to oust Villa and to hand over the entire northern border to Carranza. That Villa had returned to Casas Grandes in Chihuahua. That Hipólito had been taken from a train in Villa Ahumada and shot after officers and soldiers had mutinied. They said that Hipólito was on his way to Juárez to betray his brother and cross the border into the United States where he controlled large sums of money in the Finance Agency’s bank accounts. The following day, Villa learned from an article in El Paso Morning Times that the United States might recognize Carranza.

Oblivious to all the rumors, and without quite believing the news about Carranza, Pancho commenced the mobilization of the Division of the North’s 12,500 men towards Sonora on October 15. The force was split into more or less smaller groups to make it easier to supply them. Five hundred cows went along. Banda rode the trains in Casas Grandes detaining deserters.

The march was very slow going in short day-long lengths, but there were no problems for the first fifty kilometers.

The lack of water, however, was a serious problem. An army like this one could suck a well dry in a few minutes and it could not live on rabbits. The cattle they brought in tow were soon slaughtered for lack of water. Of the five hundred beef critters that began the expedition, only a few dozen remained. They killed horses and mules as need be and left unused carts and wagons behind. There are conflicting reports about the prevailing weather; although many witnesses spoke of frost and snow and of terrible cold, US historian Thomas Naylor reviewed the events and mentioned nothing about cold and ice, instead, October was a marvelous month and, aside from some rain, the climate was hot.

On October 19, they entered Púlpito Canyon, the most inaccessible spot separating Chihuahua from Sonora. Valadés described it as a “Path over rocks, flanked by granite walls up to two hundred meters high, they advanced in a thin line, there were parts of the canyon that were only two meters wide, the artillery pieces were jerked and jolted along the way.”

After three days, the column crossed the eight-kilometer canyon, passing through ravines that were six or seven meters wide. At times they had to force their way by dynamiting through rock. The generals dismounted to help push the carts. At the two-kilometer mark, chaos broke out and they lost six pieces of artillery. The army that emerged from the canyon was reduced to rags.

They say that Villa, upon hearing about the lost artillery, “just looked at the hill.” Some analysts suggest that Villa lost one-quarter of his troops during the passage owing to desertions and losses. A letter from Hipólito from Juárez reached Villa in the midst of the crossing with information about the potential break with the United States and the Division’s financial problems.

At the canyon’s exit, Villa reviewed his forces while mounted on a stallion. The cavalry was divided into two columns, the infantry moving along a very rough cart path towards the interior of Sonora. The region was extremely dry. Villa wet his handkerchief in filthy water in a cave to wet his lips. This march of seven thousand men seemed mad.

Villa later spoke of “the unending fatigue and hardships suffered by his forces during the twenty-five-day journey through the arid and harsh Sierra Madre, transporting forty-two heavy caliber cannons through areas without cart paths that were difficult enough even for riders to get through.”

A firefight broke out with a patrol of Carrancista scouts in the outskirts of Baviste. They were from one of Calles’ columns who had been charged with dynamiting Púlpito Canyon, but they had arrived too late.

On October 26, Villa entered Colonia Morelos, seventy-five kilometers to the south of Agua Prieta. Pancho gave a speech to a gathering of thirty residents. Although his relations with the Mormons were usually good, he was very angry with the Americans. He began by saying that the Mexicans should free themselves in their own country and then began ranting against the Anglo-Mormons. The assembly then decided to not permit the Yankee-Mormons, who had illegally taken possession of the land, to come back. Villa offered them arms and ammunition to defend themselves. When he returned from the “Battle of Agua Prieta,” he promised he would provide funds to reconstruct the mill and the dam. Villa and the thirty residents then signed a document.

The following day, an envoy from Silvestre Terrazas, a certain Unzueta, who had passed along the northern side of border, brought copies of American newspapers, confirming the recognition of Carranza’s de facto government by the United States on October 19. He also brought letters from the commission composed of González Garza, Ángeles, and Chao, reporting that all doors had been closed. Villa listened with apparent calm as Medina translated the articles from English and mulled things over. He probably had been advised that Manuel Chao had retired from the struggle. After all, on October 22, in New York, he had published a manifesto, a “Note to the Mexican People,” where he declared he would remain outside of politics and hoped that Carranza could pacify the country. There were no references to Villa in the text. It was a friendly desertion, but at the end of the day, it was still a desertion.

Silvestre reported that US recognition had provoked disorders in Chihuahua and that only Gen. Limón and Escudero’s composure—and without doubt that of Terrazas himself—had kept things under control. The recognition implied, among other things, that munitions sales to the Villistas were illegal. The US press was also saying that Villa would seek exile in the United States, claiming to know him better than he knew himself. As if there weren’t enough, Villa learned of Severino Ceniceros’s desertion. Villa would say years later to Elías Torres, “I had such courageous friends that they all switched sides when the time came.” But in the midst of all this, there was one good piece of news, that is, on October 21, Urbalejo had captured Naco, the other important border town in the area between Sonora and Chihuahua.

Over the following days, and despite the difficulties, the column’s progress towards Agua Prieta continued like clockwork and on October 30, Villa arrived at the Slaughter ranch. With their presence discovered by Calless’ scouts, the news broke in Douglas, on the other side of the border. Carothers, who happened to be there at the time, telegraphed the State Department that Villista troops were eighteen kilometers from Douglas and that a US patrol had spoken to them along the frontier. That night, a group of Villistas—who had approached the Rio Grande for its water—met with journalist John Hart, who returned with them in order to interview Villa.

Calzadíaz placed the interview at a mine called El Tigre.

“Are you Gen. Villa?” asked Hart.

“You’re looking at him,” replied Villa.

“Is it true you are going to attack Agua Prieta?”

“That’s my business.”

“How many cannons do you have, my general?”

“Count them when you hear them roar.”

Then Villa asked if it were true that the United States had recognized Carranza, and when Hart confirmed it, Villa turned with an hasta luego (see you later) and rode off on his horse. It would be best to dig a ditch thousands of kilometers wide between the two countries, Villa said many years later, and Yankees could keep his previous flattering and friendly comments wherever they would fit.

What Villa did not know was that things were, in fact, even worse. The US was letting Obregón transport fully-armed Mexican troops through American territory. While Villa was approaching Agua Prieta, Gen. Serrano and Gen. Eugenio Martínez were traveling by train from Eagle Pass (Piedras Negras, Coahuila) to Douglas (Agra Prieta) with a column of between 3,000 and 4,000 men. Gen. Scott would later explain, “I tried to use my influence to prevent the Carrancista troops from crossing the US border, but I was not that powerful [. . .]. We betrayed him in the Sonora campaign.”

On October 31, after a sixteen-day march from Casas Grandes and thirty-eight days from the departure of the first contingents in Chihuahua, the Villista column entered Agua Prieta. “Finally, after three weeks of hardships, ragged, dying of hunger and cold, we came face-to-face with Agua Prieta’s trenches,” Villa remembered. And what they saw could not have raised their spirits.

Agua Prieta is a small city, really a town, five blocks by seven. There were very few buildings but there was a Masonic temple, the Curious Café, and a theater, the Ramona, along with two hotels, the Central and the Mexico. Planks were laid on the rough ground to walk over and there were cellars everywhere, secret passageways, tunnels, ammunition depots. Along just a two-and-a-half-kilometer front, Calles had placed two hundred dynamite mines and eight thousand meters of barbed wire, at some spots electrified, shallow fox holes and trenches one meter deep covered by steel plates and sand, eighteen machine-gun nests, floodlights to illuminate any potential nighttime attacks, and he had the US border to his back to supply his forces. It was a fortress “as good as those they were using in the European war,” observed one spectator. He could count on a 1,500-strong garrison plus the 3,000 or 4,000 other reinforcements arriving by train, along with five artillery batteries.

Curiously, the Americans were more or less as prepared as they were in Agua Prieta. Did they think that Villa’s indignation over the recognition would prompt him to fight them? The Douglas garrison grew to three infantry regiments, an artillery company, and cavalry troops. Trenches were dug from Douglas to the hills, to east of the city, and artillery units took up positions.

On November 1, Villa was at the Gallardo hacienda facing Agua Prieta. His advancing troops could be seen clearly from the United States. At midday, the Carrancista artillery started bombarding them. The vanguard of Villa’s troops found pamphlets signed by Calles in which he offered amnesty, a train ticket home, and a cash payment for any Villista who surrendered with their arms. As soon as they neared the trenches covered with barbed wire, they were fired upon by the Carrancista cavalry and then raked by artillery fire. When the shooting started, a Villista barrage that fell short revealed that the fields leading up to the city had been mined. Powder and smoke, earth thrown into the air by shells and mines, darkened the battlefield.

At nine in the morning, J.B. Vargas, suffering from a small leg wound, made his way toward the border, one mile to the east of Douglas. Approaching a slaughterhouse, he ran into a group of workers who he asked to connect some hoses he could bring over to the Mexican side. The army had gone twenty-four hours without water because the windmills that ran the area’s wells had been destroyed. Some American women traded buckets of water for the soldiers’ straw hats. A US officer approached on behalf of Gen. Funston and asked to meet with Villa. Later, with the barbed wire fence separating the two, Gen. Funston met with Villa with Juan N. Medina acting as translator while a journalist named Roberts accompanied Funston. Villa reproached the treacherous attitude of Wilson’s government. Funston issued veiled threats to Villa against his bullets landing in Douglas. Villa replied that if he didn’t want his bullets to hit Douglas, Funston ought to allow him to attack Agua Prieta from the US side. The meeting lasted ten minutes and the American general simply reported that Villa’s attitude was “very satisfactory,” adding no further details.

At 11 a.m., according to some, at 1:35 p.m. according to others, an artillery duel commenced to little effect; although it killed a great many Carrancista horses and destroyed a large number of houses, it did not affect the city’s defenses. Just as the battle got under way, Obregón’s reinforcements commanded by Serrano began arriving in Douglas, having crossed over US territory. They suffered many casualties because they arrived at the moment the bombardment started up. Calles’s band struck up a tune and Villa responded with a final broadside.

Fighting continued all along the perimeter for the entire afternoon with little progress. At some point, Gen. San Ramón, the infantry’s commanding officer, died. The Villista cavalry carried 1,000 infantry soldiers on horseback and deposited them two hundred meters from the trenches. Cannon smoke filled the air around Agua Prieta. Villa began planning a nighttime attack.

When they launched the attack that night, the Carrancistas lit up the floodlights. Gen. Rodríguez ordered a withdrawal. Villa always believed that the lights that destroyed their nocturnal attack were located on the US side. But it wasn’t true, even if the electricity did come from Douglas and the lamps had most likely been manned by American mercenaries.

Villa wrapped up the disaster, “That attack where hundreds of unlucky men lost their lives on electrified barbed wire, which the Carrancistas powered with current from the American side, couldn’t have been made under worse conditions since, and to paint the picture even blacker, our consul in Douglas took off with the money that the governor of Sonora sent him to buy food and canteens; and many of us, in order to quench our thirst, had to drink water from the drainage ditches, straining it through our bandannas, and to eat, we had to slice up the haunches of our own mounts.”

The following day, Villa convened a meeting of generals at a point called La Morita. Ocaranza, Juan N. Medina, Madinabeytia, José Rodríguez, Isaac Arroyo, Gonzalitos, and Baudelio Uribe all attended. The lack of water had reached a crisis point, the army and their 7,500 horses and mules in tow had dried up all the water sources around Agua Prieta. And, if Diéguez’s brigade moved north, they might be trapped. It was decided to abandon the siege of this hardened position and move towards Nogales. The generals were furious at the United States. They said that US soldiers had fired machine guns at the Villistas from the slaughterhouse. However, as often as the story was repeated, it wasn’t true. Nonetheless, the rumor took hold. Villa explained “. . . I prevented my forces from launching themselves towards American territory, as they were fully justified in wanting to do.”

Sporadic fighting and artillery fire continued, but on November 3, they lifted the siege, withdrawing the artillery and part of their advanced forces. On November 4, taking advantage of the fog, the rearguard followed suit. They left behind 223 dead and carried 376 wounded with them. They were pursued by cavalry forces led by Lázaro Cárdenas, who was defeated and turned back by Isaac Arroyo in a Villista counterattack.

Pancho established his camp in Villaverde, a few miles from Cananea Copper as the pastures to the southwest of the city were excellent. Two American medical doctors named Thigpen and Miller arrived from Bisbee, offering to treat the wounded. At first, Villa thanked them for their offer, but someone must have told him they were acting as secret agents for the US because Villa became enraged, ordering them detained and condemning them to the firing squad. Soon after, he ordered the arrest of Hamilton, the superintendent of Cananea Copper, and Wiswall, the manager of Cananea Cattle, locking them up in the local jail. Sometime later, he interviewed them. Villa, very angry, informed them that he was going to use the enterprise to reprovision his army and he would charge a tax on copper shipments destined for the US Hamilton told him that he would have to cross the border to get what he had asked for and went to Naco, Arizona. Finally, Villa seized a truck filled with food, including 20,000 pounds of flour, five sacks of coffee, and several sacks of salt, which he shared around his camp, along with 175 horses and 1,500 cattle.

A second meeting was then held. The Cananea managers diplomatically interceded with Villa, demanding the lives of the doctors be spared. Villa replied angrily that they were not doctors but rather spies. When he was shown proof, he refused to believe it, “I believed they were spies.” They were finally released in exchange for $25,000. The company convinced Villa to issue them a receipt to be deducted from the taxes they were to pay on copper shipments and eventually managed to get partial restitution from the Carranza government. One day later, Carothers reported—exaggerating the matter—that Villa had demanded a forced loan of $25,000 from four US companies in the territory he controlled.

Villa rebuilt his brigade, starting with supplies. The lists of purchases from Douglas and El Paso (via Douglas) were preserved. Strangely, his agent in El Paso was Sam Dreben, his old machine gunner, who had worked for anyone who would hire him and now sold him 200 boxes of sardines and 1,444 sacks of flour. Unusual items for an army in the midst of a campaign appeared in the list of more common items from Meadows Drug Store in Douglas, including mercurochrome, bicarbonate, bandages, cotton, and gauze along with one dollar spent on white Vaseline, sixty pages of paper, and fifty envelopes.

On November 5, Villa published a long manifesto in which he declared that “Venustiano Carranza is trying to sell our country.” Employing the ritual rhetoric of these kinds of statements—owing to his secretaries’ infamous pens—the manifesto told the story of the revolution and the Division of the North. Katz and Almada attributed this one to Federico González Garza, but he wasn’t in Sonora at the time, and it was most likely written by Enrique Pérez Rul who was accompanying him. It rejected the accusation that the Villistas were reactionaries and explained that they had, in fact, accepted former federales into their ranks “as long as we were convinced of the firmness of their principles [. . .] and a very small group of them are still with us.” It then addressed another theme, “The recognition of Carranza has astonished the whole world” and stated that it had “copied from some North American papers some conditions imposed on Carranza by Wilson,” including: a ninety-nine-year concession to the bay of Magdalena and the Tehuantepec railroad; US approval of the ministers of Foreign Relations, State, and Finance; control over national railroads, Pablo González to be named future president of Mexico, and return of some of the property expropriated from foreigners.” It concluded that “Wilson’s attitude relieves me from making guarantees to foreigners.” Despite the fact that the full text of the manifesto was published in the Chihuahua press several days later, US agents overlooked it. And even a character as unfriendly towards Villa as Frank Miller, the assistant chief of the Columbus garrison, later conceded, “It has to be recognized that Villa had reason to be bitter.” Yet the manifesto was not merely bitter, it also had the ring of a declaration of war on the United States and its interests in Mexico.

A few days later, the Division of the North was mobilizing. They passed through Cananea, where Villa gave a speech to the workers who cheered him, and then they set out looting the rich, including the shops, the mines, and the Banco de Cananea. Although there were 5,000 Chinese people in Cananea, the Villistas did not bother them. They next went to Nogales, where Villa met with Gov. Carlos Randall. A US journalist named John Harris spoke of “popular enthusiasm.”

Villa set up shop at the Customs office, strangely, on the Arizona side of Nogales. While he was there, he learned about Francisco Urbalejo’s defeat in Hermosillo, who had been forced to give up the capital to Diéguez as well as the death of one more of the Division of the North’s generals, Orestes Pereyra, who was captured and shot on November 9, in El Fuerte, Sinaloa. Pereyra’s death was celebrated by the Carrancistas, and it caused a sensation in Durango. The disappearance of Villismo’s agrarian reform leader induced telegrams with messages like, “They say the price of cotton is going to increase.”

Villa departed the region on November 14. He left a group of 500 men under José Rodríguez to keep the road open to Chihuahua while he headed south with the rest of his troops. Rodríguez continued retreating in the face of an expeditionary force from Agua Prieta. The Villistas were forced to leave their wounded behind in a hospital in Naco, which was captured by the Carrancistas on November 15. The shootout spilled over into the US side of Naco, leading one reporter to remark that not a single house was left without a bullet hole, “some had as many as fifty.” However, the United States, following its double standard, filed no complaints whatsoever. Álvaro Obregón arrived in Naco to personally assume leadership of the campaign in the northern part of Sonora.

Villa moved south towards Hermosillo on November 16, arriving in Alamito two days later, some sixteen kilometers to the northeast of the capital. Urbalejo threw Villa a barbecue and met him dressed in a Panama hat and a bomber jacket despite the cold.

They hadn’t even had time to digest their food when they were attacked by Carrancista infantry led by Ángel Flores at four o’clock in the afternoon, who had managed to seize the rail cars used by Urbalejo’s Yaqui fighters. After a half hour of fighting, during which Urbalejo’s troops suffered 600 casualties, Villa, who had brought only his guard with him, retreated towards the Zamora station with the Yaquis to get reorganized. In his report, Flores noted that Villa “fled towards the north” and concocted a story about fighting 2,000 riders commanded by Madinabeytia. The Yaquis lost two trains, including a supply train and a repair train. The Carrancistas withdrew back towards Hermosillo.

The Villistas assembled in Carbó along with Urbalejo’s Yaquis with the exception of Rodríguez’s brigade who kept up a game of hide and seek with Obregón in the north of the state. Preparation for the attack on Hermosillo got under way on November 20. Villa was suspicious of the Yaquis—not knowing anything about their fighting capacities—and had no confidence in them. Some of his native Sonoran officers in the brigade set him straight and convinced him of the “strength and honesty of these troops.”

José Herón González was the first to arrive with infantry. Gonzalitos had come to prominence during the battles in Bajío as a military commander and was now a key leader in the Sonora campaign. Rafael R. Muñoz described him: “A tiny boy, whose small stature was ridiculous compared to the giants in the Division of the North. Fine as a young lady, with a graceful walk, a ruddy complexion, who could not put up with the cold north wind and the sun backing down during the campaign [. . .]. He walked very stiffly, with his shoulders thrown back, his head erect [. . .] his hat, one of those discarded by the American army, with the rim bent up on the left side and pinned to the hat’s crown with a tricolor cockade [. . .] he was an athlete [. . .] he gave advice when no one asked for it, orders to those who were not under his command.” Ignacio Muñoz added, he was “small, thin, an almost flutelike voice, no mustache, and you needed a corkscrew to get any words out of him.”

On November 20, the Villista column moved towards Hermosillo at a medium trot, deployed in their order of battle. An order went out to set fire to scrub brush in order to cover the advancing line that stretched out over ten kilometers. “It looked like a line of locomotives moving over hills and plains at top speed towards Hermosillo.” The first clash took place at the Pesqueira station. The fury of Urbalejo’s Yaqui fighters owed itself to their desire to recover their families who had been kidnapped by the Carrancistas and carried off to Hermosillo. Gavira withdrew in the face of an overwhelming enemy that burned everything in its wake. “The enemy fell on us just at the moment we began to move back.” Gavira suffered “important losses,” some 250 soldiers and 15 officers.

But the victory would come at a high price. Rafael Muñoz explained, “To the north of Hermosillo, the plains were covered with thick scrub plants, including mezquitillo, ironwood, garabatos, chayoteras covered in spines, palms [. . .]. The railway tracks go along a narrow path in disrepair dotted with telegraph posts [. . .]. It was already getting dark when Gen. Gonzalitos appeared before the cavalry commander and suggested that he ride out front as in the battle of Marengo. The cavalry commanders, without knowing much about Marengo, answered that Villa had ordered them to remain behind the infantry, hoping the infantry would contact the enemy first.” Herón Gonzalitos decided to set out as a scout on a “big quarter horse, half again as tall as any other in the Division,” he looked like a jockey. He was passing by the vanguard of the Yaqui troops when he was shot by a group of retreating Carrancistas. His body was recovered the following day.

Villa halted his column in order to reorganize it, but the Yaquis arrived on the outskirts of the capital to the east and had taken control of the hills, having chased the Carrancistas forty kilometers. Diéguez couldn’t shake them. After being informed of the Villistas’ advance, Obregón granted Diéguez the authority to pull back towards Sinaloa. Diéguez considered fleeing towards Mazatlán, but decided against it after Ángel Flores convinced him that Villa would massacre them in any such retreat. Thus, the battle of Hermosillo took a turn.

On November 21 and 22, Villa continued his furious assault all along the line, entailing thirty hours of house-to-house combat. The Carrancistas claimed that Villa had offered the Yaquis the right to loot the city and significant desertions commenced. Gavira and Diéguez saw a defeat coming and began thinking about retreating towards Sinaloa; however, Madinabeytia’s riders had cut them off from that route.

On the first day of the battle, Villa asked José Rodríguez to join in. Rodríguez was in Bacoachi after having broken through the Carrancista encirclement in Cananea, but he ignored the message. Villa then sent a commission to judge his refusal, but it never returned. Although some say that what did return was a message to Villa from Rodríguez, announcing that he no longer recognized him as his commanding officer, nor did he recognize the Division of the North. Future events would disprove this version. Rodríguez only left Sonora after a thousand little adventures and clashes, looting mining villages along the way as he was on the run from all sides.

At dawn on November 23, fighting unexpectedly stopped and Villa ordered a withdrawal all along the line, pulling back towards Alamito. Had Villa decided to give the Division a rest to attend to its wounded? A break for his men who had completed an infernal march in order to prepare for an offensive the next day? Or was it because Martín Unzueta had delivered messages informing him that his commission in the United States had concluded that there was no point in further talks because the United States had definitively taken Carranza’s side?

Misinterpreting the order to withdraw, Luis Buitimea’s Yaqui troops, whose children and wives had been captured by the Carrancistas, decided to surrender. Villa didn’t understand what was happening and convened a conference of the remaining Yaqui commanders.

Mulling over his situation, that night Villa wrote a personal letter. At sunup the next morning, a rider carrying a white flag delivered Villa’s note to Gen. Ángel Flores in which he told him that Carranza had signed an agreement to sell the country to the gringos. “According to the press,” as had been previously mentioned, the pact would cede Bahía Magdalena for ninety-nine years, along with the Tehuantepec railway and the petroleum region, while the gringos would also approve ministerial appointments; indemnity payment would be made to foreigners and confiscated property would be returned; the national railway would remain under their control until the debt was paid off; Pablo González would serve as acting president, and, in exchange, he would receive a payment of half-a-million dollars from the United States. “Under this pact [. . .] we accept the Yankee protectorate.” He pointed out that this was the reason why Carrancista troops had been permitted to pass through Agua Prieta by the US and appealed to Flores’s patriotism. “When the United States wishes to tread on our national territory, will you allow them to do so?” He signed off by asking for his opinion.

Villa was convinced that there was a secret pact, mentioning it twice. This explained why the US had betrayed him and adopted a hostile stance in favor of Carranza and he felt this had only been confirmed by his conversations with Duval in Guadalajara and the events of the last few weeks. He didn’t put much stock in Carranza’s patriotism and didn’t think too carefully about some of the inconsistencies in the supposed agreement. For example, a half-a-million dollars was much less than Villa himself had stashed in various hiding places to finance the revolution.

Diéguez, meanwhile, reported that after thirty hours of fighting in Hermosillo, the enemy had been turned back and was fleeing to the north; he then informed his troops that all that remained was one more push to strike the final blow. Yet, it wasn’t the fighting or the capacities of the Carrancista general that determined the battle, it was Villa’s own doubts.

During a campaign which had been replete with indecisions, it was time for one more. Pancho Villa had been affected by his experiences in Bajío; perhaps he was still no weaker or less able than his enemies, but doubt and insecurity pursued him like a new ghost. How could we expect otherwise? In four months, he had lost dozens of his commanders, including his best friends; he had been defeated five times by an army which he held in contempt (“better to have lost to a Chinese”). He needed time to recover from so many blows.

Villa remained in the outskirts of Hermosillo until November 25, waiting for a reply to his letters that never came. More Yaqui fighters deserted. Villa sent the civilians to the border to return to Chihuahua clandestinely via the United States. This same day, a confrontation broke out in Nogales between the Villistas and the US consul which almost ended in a gunfight. Randall explained it to Villa, telling him that the Villistas were very angry about the blockade of food imports.

On November 27, Villa met with his generals and proposed giving up on the Sonora expedition and that he would have to return to Chihuahua to learn their destiny. He had received word that a column of 10,000 men under the command of Treviño was moving from Torreón to Chihuahua, remarking that “I knew the enemy, counting on support from the Americans, was considering mobilizing by train from the United States to seize Ciudad Juárez.” Juárez was his first and most important “base of supplies.” Additionally, he received information of another plot in Chihuahua, headed by Gen. Lauro Guerra, which ended with detentions and firing squads.

During the last days of November and early December, Villa disappeared. The earth seemed to have swallowed him up in the heart of Sonora. Reports from the El Paso Morning Post, the region’s most influential newspaper, stated that he had gone to Bacoachi to meet with Rodríguez. There were rumors, spread by the media, that Villa was going to attack the United States in retaliation for its betrayal. On November 27, some reports situated him to the east of Hermosillo and others announced that he was moving south to attack Sinaloa. The most creative new sources wrote that he had gone to the Bacatete region, accompanied by Urbalejo to meet with the Yaquis to propose a holy war. Still other rumors stated that he was organizing a guerrilla campaign to lay waste to the Tucson, Arizona area.

The truth is that Villa, as he withdrew from Hermosillo, went north towards Nogales, but then turned east in Querobabi in search of Rodríguez. He then gave up on the idea and once more headed south. He passed through La Colorada, fifty kilometers to the south of Hermosillo on the opposite side of the city from where Diéguez’s scouts were looking for him. In Tecoripa, Urbalejo and his 200 Yaquis abandoned him because they didn’t want to fight outside of Sonora. Another parting of the ways took place in Mátape where a group with Villa’s remaining seven cannons broke off, dismantling the big guns. The remaining troops headed southeast. Of the 12,000 men in the Division of the North who began the campaign, only 3,000 were left.

On December 1, the group guarding the cannons came across the village of San Pedro de la Cueva, where some ninety (others would say sixty-six) locals ambushed and fired on them. Six of the original sixteen Villistas were killed. It was never clear why the villagers ambushed them. Later, some claimed that the locals did not believe they were Villistas. Then, what did they believe? After a series of shouts and explanations, the firefight stopped. Macario Bracamonte (others would say that it was Margarito Orozco), who was in command of the squad, told the locals that Villa would be enraged, and they had better abandon the village. Others reported that the ambushers, upon seeing the avalanche of Villistas coming their way, took off for the hills upstream.

Soon after, Villa’s main column arrived. He was informed that his squad had been fired on and became furious. His men seized the village while Villa listened to Bracamonte’s version of events. While some Villistas were looting (other sources claim they were searching for the ambushers), someone shot at Pancho’s nephew, Manuel Martínez, killing him.

“What is happening here? What’s going on?” they say Villa asked. He then ordered that all the men in the village be shot. His men dragged them out of their houses, pulling them away from their children, their boys, and their wives.

At seven in the morning on December 2, seventy-seven men were shot. There is a horrific photograph reproduced by Alberto Calzadíaz that shows the massacre’s widows and orphans in front of the wall where their fathers and husbands were shot, in which small hand-painted crosses can be seen painted over the bullet holes.

Later, it was claimed that one man managed to escape Pancho’s fury dressed as a woman; another spoke to Villa, who let him go; one more survived after his wife explained that he had just arrived from the United States; one more affirmed that he had ridden with Villa in Chihuahua. The local priest interceded three times on behalf of one of the condemned, but on the third time, Villa shot him after being told that the priest had whipped up the ambushers. Three Chinese men died in the San Pedro Massacre. As their names were never known, the villagers carved Federico, Jesús, and Rafael on the gravestone.

On December 2, the column arrived in Batuc, where the reception, unlike in San Pedro, was very warm. They once again crossed the Sierra Madre along unmarked paths, almost without food. Gilberto Arzate recalled how they were “crossing very bad terrain [. . .] many people died from hunger and thirst because there was nothing to be found.” Col. Nieto stated that “the cold was terrible, we were in the middle of real mountains, injured, lacking food [. . .] it started raining again and, at one point, it snowed.”

Villa told Puente that on “one occasion, some of the wounded boys begged me to leave them together in a ravine because they couldn’t stand to suffer any longer, there was a blizzard that afternoon and they wouldn’t feel death under the snow. When we said goodbye, one of them, with an almost other-worldly voice, told me something that left a deep mark on me: ‘Farewell my general, you never backed down.’”

The Villista José Nieto provided an epilogue when he described how the first relief they were offered came in Tutuca, where Tarahumara Indians gave them food and shelter. “The state of Chihuahua was our home.”

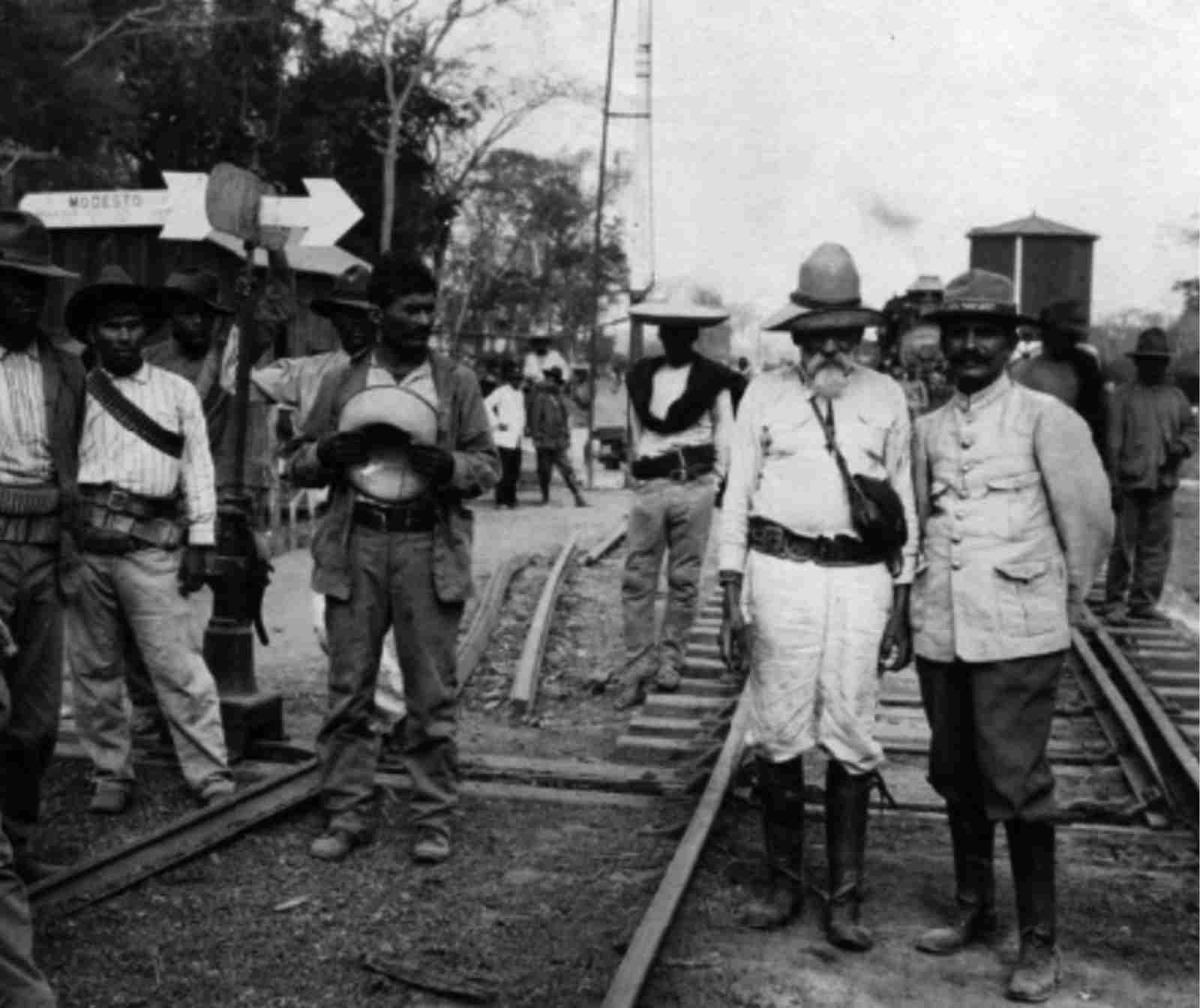

Francesco Urbalejo (right), a Yaqui, faught in the Sierra Madre Occidental against the Maderistas. In August 1914 he seconded José María Maytorena against Venustiano Carranza, fighting on the side of the Conventionalista faction. Mexico City, 1914.