15.

ELIJAH IS COMING

I am working like a galley-slave, an ass, a brute,” James Joyce wrote in a letter. “I cannot even sleep. The episode of Circe has changed me too into an animal.” By December 1920, he was suffering from another episode of iritis in a dark apartment on rue Raspail. His eyes had gotten worse since his surgery, and the heat from the gas stove, he thought, was the only thing warding off a full-blown attack of glaucoma. Joyce was so cold in their last residential hotel that he wrote with blankets over his shoulders and a shawl wrapped around his head. He wrote whenever he wasn’t bedridden with fits of pain, and he thought about writing whenever he was. He started “Circe” in April 1920 and estimated it would take three months to complete. By December, he was on his ninth draft, and “Circe” was still expanding, insert by insert, as he drove his pen late into the night, his pupils gaping in the room’s meager light.

Joyce finally reached the midnight of his book. In the “Circe” episode, Leopold Bloom follows Stephen Dedalus into Nighttown, where an elaborate fantasy unfolds in Bella Cohen’s brothel on Tyrone Street before Bloom rescues Stephen from a fight with British soldiers, brushes the dirt off his shoulders and walks him home. Nothing was interior now—there were no thoughts, no fears, no memories or nightmares that were not acted out for the people in the brothel to see, and the brothel contained everyone.

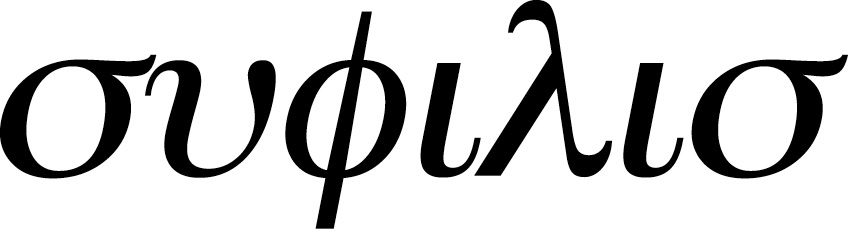

The presiding spirit was the enchantress in Homer’s epic who turns Ulysses’ men into swine. Before wily Ulysses approaches Circe’s hall to rescue his men, the god Hermes gives him an herb that will protect him from her spell. The herb that saves Ulysses is called Moly (things like this were no coincidence). Joyce wondered if the word syphilis had its origins in Circe—perhaps it was Greek:  . Su + philis. “Swine love,” the spell that drove men to brute madness. After Ulysses compels Circe to transform his men back into humans, she regales them with a celebration that lasts a full year. Joyce toiled on “Circe” months longer than he planned. The episode became at turns a carnival, a nightmare, a phantasmagoria and a hallucination. Miracles are performed and humiliations enacted. Genders change. Hours dance. Moths speak.

. Su + philis. “Swine love,” the spell that drove men to brute madness. After Ulysses compels Circe to transform his men back into humans, she regales them with a celebration that lasts a full year. Joyce toiled on “Circe” months longer than he planned. The episode became at turns a carnival, a nightmare, a phantasmagoria and a hallucination. Miracles are performed and humiliations enacted. Genders change. Hours dance. Moths speak.

Nearly everything and everyone the reader has seen through the day returns as a nightmare. Gerty MacDowell reproaches Bloom (“Dirty married man! I love you for doing that to me.”). Blazes Boylan tosses him a coin and hangs his hat on Bloom’s antlered head (“I have a little private business with your wife, you understand?”). Bloom shakes hands with the blind stripling (“My more than brother!”). “Bronze by gold,” the prostitutes whisper. The nanny goat, dropping currants, ambles by. Father Dolan emerges to upbraid Stephen for the glasses he broke in A Portrait when he was six years old (“lazy idle little schemer”). The ghost of Stephen’s mother, like Joyce’s mother, appears with green bile trickling from her mouth (he asks her to tell him that she loves him). Bloom’s father, who committed suicide years ago, touches Bloom’s face with “vulture talons.” The long-awaited Elijah finally arrives and begins to dispense judgment (“No yapping, if you please . . . ”). Rudy, Bloom’s son, appears as he would have if he had survived infancy.

—

JOYCE TOOK NEARLY A MONTH to respond to Quinn’s urgent letter about the charges against the “Nausicaa” episode, and when he did, he sent a coded telegram.

SCOTTS TETTOJA MOIEDURA GEIZLSUND. JOYCE

Quinn’s office clerk, Mr. Watson, obtained a copy of the Scott’s code manual and translated Joyce’s message. “I have not received the telegram you mention. You will be receiving a letter upon this subject in a few days giving information and my views pretty fully. I think a little delay will not be disadvantageous.”

Quinn cabled back and insisted that Joyce cease serial publication immediately. If they were lucky, the DA might drop the charges. If they were unlucky, he would add more counts to the indictment. But Joyce wanted to keep his Little Review audience, and if he was unwilling to compromise for editors and printers, he was even more unwilling to compromise for law enforcement officials, no matter what his lawyer’s advice. Quinn received another telegram from Paris.

MACILENZA PAVENTAVA MEHLSUPPE MOGOSTOKOS.

Watson decoded it: “Private and reliable information received. Number in dispute has been issued. Pending receipt of your letter matter will remain over.”

But the matter was far from over, and Quinn had to come up with a plan. The case was scheduled to go before a panel of three judges in December, and he decided he would file a motion for a jury trial instead, which would slow the process down. The transfer motion would have to be filed and scheduled for a hearing before an overworked grand jury could get around to issuing an indictment. By the time a jury of twelve was selected and the magazine convicted after a full trial, it would be the autumn of 1921, and as long as the legal proceedings were grinding forward, they could publish a private edition of Ulysses. That is, instead of selling the novel in bookstores, a publisher would print around one thousand high-quality copies and mail them directly to readers placing orders in advance.

Technically, the book would be legal before the ruling against The Little Review was handed down, and Quinn figured Sumner and the DA were less likely to prosecute a book circulating privately than a magazine available to unsuspecting young women. A deluxe private publication could sell for as much as eight to ten dollars per copy, about four times more than the average book. At 15 to 20 percent royalties, Joyce could earn as much as two thousand dollars. All he would have to do is finish his novel before the legal clock ran out.

Quinn was trying to convince Ben Huebsch to publish a private edition of Ulysses, but the impending trial was making him leery. Huebsch was the obvious option for Joyce. He had published Dubliners and A Portrait, and he admired Joyce’s new book. Quinn urged him to sign a contract even before The Little Review landed in court, and by December 1920 he decided that he and Huebsch needed to have “a showdown.” He wanted Huebsch to make an offer for Ulysses while the risks appeared as minimal as possible—the last thing Huebsch needed was to see the details of the trial in the newspapers.

The showdown was at Quinn’s apartment, and Quinn drew first: Joyce would never agree to any cuts or alterations, he told Huebsch, and it was a “practical certainty that if Ulysses were published here without any alteration of the text, it would be suppressed, involving your arrest and trial.” Quinn was starting, apparently, with the bad news. Huebsch already knew the good news. Boni & Liveright sold private editions of several daring books, and they escaped prosecution every time. While none of their books had indicted excerpts, Quinn assured Huebsch that magazines and books were judged by different legal standards: the more discreetly something circulated, the more likely it would escape prosecution. And a conviction against The Little Review could be a good thing. It would end the serialization of Ulysses, and the demand would be higher if a few chapters hadn’t seen the light of day.

Quinn wanted fifteen hundred copies printed on high-quality paper and priced somewhere around ten dollars so that Joyce could get a royalty of two dollars per copy. That would give him three thousand dollars for Ulysses, more than Quinn mentioned to Joyce. But Huebsch was nervous, and when Quinn sensed that he wanted to see how the trial played out, he planned to approach Boni & Liveright for a quick contract. But without Joyce’s approval, he had to keep stalling.

—

QUINN FILED THE MOTION for a jury trial in January 1921, and in a concluding flourish he argued that the charges caused The Little Review “serious financial loss.” The longer the ban continued, he claimed, the more it would damage their finances. The Little Review struggled through 1920, and it went into a tailspin after Sumner walked into the Washington Square Book Shop. Quinn and his friends had withdrawn their financial support, leaving Anderson and Heap desperate for subscribers and benefactors. Over dinner with Anderson one night, a patron demanded sexual favors for his continued support. She was furious. The Little Review also needed content. Ulysses was, more or less, keeping the magazine afloat.

Jane Heap wrote to Joyce for the first time: “We cannot apologize for the recent deletions,” she wrote in green ink. “We can only suffer with you. Our entire May issue was burned by the Postal department and we were told brutally that we would be put out of business altogether if we didn’t stop ‘pulling that stuff.’” Then she turned to the pressing issue: the Ulysses installments were coming too slowly. They were parceling out the text in smaller chunks, but it wasn’t enough. Could he send short stories or poems? “We cannot pay well at present,” she confided. “We live only because we are able to fight like devils.”

Following the obscenity charges, Anderson and Heap halted publication for three months. In December 1920, they interrupted a performance of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones at Washington Square’s Provincetown Playhouse and asked the audience for contributions to defend Ulysses and save the magazine from bankruptcy. Whatever they gathered at the theater, it was just enough to publish a December issue. The editors announced that the charges forced them to raise subscription prices from $2.50 to $4.00.

Meanwhile, Quinn pressed Joyce to finish Ulysses quickly. Sumner and the DA were increasingly impatient with procedural delays, and Huebsch, still inching toward an agreement, needed to publish it by the fall to avoid censorship. Joyce answered with another coded telegram saying that the finished manuscript was only a few months off, but he wanted more than two dollars per copy. “Make following counter proposal: $3 $3.50. Withdraw offer unless accepted immediately.”

Joyce reasoned that a limited edition of Ulysses—already longer than most private editions—could retail for more than ten dollars. But nobody made agreements like this “immediately”—even when the book didn’t have legal problems. Whether Joyce was too far removed from the situation in New York or too absorbed in his own writing, he simply wasn’t worried. He cabled again five days later in code: “In financial difficulties. Remit by telegraph as soon as possible two hundred dollars pending completion of contract.”

Quinn was astonished. Here was an impoverished author—barely able to afford a telegram—with criminal charges against a portion of what was already a long and difficult manuscript. The editors publishing his fiction were facing jail time for it, and instead of seizing any publication offer he could get—instead of thanking Quinn for trying to strong-arm a publisher into offering a contract for what would probably be a financial loss even if it wasn’t a legal mess—Joyce demanded nearly double the royalties and a two-hundred-dollar advance on a contract that didn’t even exist. Pound was right. James Joyce was completely unreasonable.

CABLING MONEY REQUESTED WILL ENDEAVOR WRITE NEXT THREE OR FOUR WEEKS DO NOT CABLE ME AGAIN ANY SUBJECT HAVE ENDEAVORED MAKE YOU AND POUND UNDERSTAND AM WORKING LIMIT MY ENDURANCE QUINN

—

THE LITTLE REVIEW TRIAL could not have happened at a worse time. Not only was Quinn shuttling back and forth to Washington, D.C., to prepare for the most important case of his life, but the country had fallen into an economic depression. Throughout 1920, wholesale prices were plunging due to a sudden drop in demand for U.S. products after the war. European agriculture recovered faster than anyone expected, and American farmers were left with large surpluses and crushing debt that ravaged both the farmers and the banks that financed them. Commodity prices dropped 46 percent in less than a year, and by 1921 Quinn found himself in the middle of a disaster. One of his biggest clients, the National Bank of Commerce, had holdings in hundreds of agriculture companies, all on the brink of collapse. Quinn himself lost thirty thousand dollars in securities that year, and there was no end in sight. “Clients, banks, corporations have lost money right and left. Soft spots developed where the surface seemed to be clean and hard. Failures, failures, failures!” Bankruptcies multiplied till corporate officers became hysterical. It was the third financial panic he had been through, and it was by far the worst—“a financial reign of terror.”

Quinn’s employees were at their wits’ end. One of his junior partners quit, and the other couldn’t handle his work because he was having domestic problems, spending late nights in Washington Square and, like Joyce, suffering acute attacks of iritis. Quinn worked on Sundays, Christmas and New Year’s Eve. He worked nights, canceled all private engagements and gave up daytime smoking breaks. The time he took to defend The Little Review was costing him his sanity, not to mention thousands of dollars in lost fees from other cases, but he was unable to say no to an artist like Joyce. “The trouble with me,” he wrote to J. B. Yeats, the poet’s father, “is that I am too damned good-natured.”

But it was Miss Weaver’s good nature, above all, that allowed Joyce to write Ulysses amid war and recession, and she tried desperately to insulate him from the financial difficulties he created for himself. Miss Weaver had begun her patronage modestly. In 1916 she sent Joyce fifty pounds, ostensibly for serializing A Portrait in The Egoist, though it was nearly as much money as the magazine grossed in a year. In February 1917, the Egoist Press published A Portrait with Huebsch’s sheets, but circumstances dulled the occasion’s triumph. Joyce’s letters over the previous three months detailed his ongoing affliction, including several collapses he said were due to a nervous breakdown, and she got her first glimpse of Joyce’s likeness when he sent her the photograph that Pound had called “terrifying,” though the sight of Joyce’s eyes moved her to compassion rather than terror.

By 1919, Miss Weaver was collecting every press clipping about Joyce she could find and losing sleep over the draft episodes of Ulysses, but Joyce was still struggling. The Egoist Press’s second edition of A Portrait sold only 314 copies in over a year, and Joyce suffered multiple eye attacks in 1918 followed by yet another in February 1919. So at the end of that month, Miss Weaver became Joyce’s anonymous donor by giving him a £5,000 war bond yielding £250 in income annually. When Nora received the letter from Miss Weaver’s law firm, she rushed to meet Joyce in Zurich and danced a jig on the steps of the tram. Two months later, Miss Weaver revealed herself as the donor and begged him to forgive her lack of “delicacy and self-effacement.”

From that point forward, Miss Weaver’s patronage was candid. In August 1920 she bestowed another capital gift of £2,000. During the late stages of drafts and revisions on Ulysses, Joyce was earning £350 per year (equivalent to more than £11,000 today) from Miss Weaver’s two capital donations, and she padded this with several small gifts over the years. She wanted to repay Joyce for the freedom she felt when she read A Portrait by giving him the freedom to write a book unfettered by marketplace constraints. And she was not disappointed, for the new novel he was writing appeared to be constrained by nothing, to be the most ambitious novel anyone had ever written. Her investment also would have granted Joyce peace of mind if he were capable of living within his means, but the apartment he rented in Paris in December 1920 cost £300 per year, nearly everything she gave him, and a high rent was not the only indulgence. Nora dressed the family in fashionable clothes. Joyce was fond of fine restaurants, taxicabs and, of course, considerable drinking. He tipped everyone extravagantly—five-franc tips for one-franc drinks, as if he distrusted the money. Add Joyce’s medical bills and it’s easy to see how he was desperate for an advance on Ulysses by the beginning of 1921.

Years of patronage attenuated Joyce’s already weak sense of practicality, which is part of the reason he thought The Little Review should continue serializing Ulysses while John Quinn fought criminal charges. Ezra Pound was less concerned about The Little Review charges now that Joyce had a patron—that, in Pound’s opinion, only made severing his connection with the magazine easier. Quinn, in fact, was the only person who understood the gravity of Joyce’s immediate legal problems, and the situation in New York became worse when Quinn’s motion for a jury trial was denied in February 1921. The judge sympathized with Quinn’s claims about the magazine’s finances, but the argument was a bit too clever. The judge sympathized so much that he decided to do the editors a favor: by denying a jury trial and holding the trial before the three judges of Special Sessions, the editors would get an earlier judgment and be back in business much sooner. Quinn received two days’ notice: The Little Review was scheduled for trial on Friday, February 4.

Quinn rushed to the DA’s office, found the prosecutor in charge of the case, Assistant DA Joseph Forrester, and introduced himself in a half whisper. For the past week, Quinn had been suffering from laryngitis, and his doctor forbade him to speak. He asked for another adjournment, and Forrester actually told John Quinn that there would be no more delays unless Sumner agreed to it. Quinn had the ear of U.S. Attorney General Palmer, testified regularly before congressional committees, changed the nation’s copyright and tariff laws, was almost single-handedly defending the federal government in the U.S. Supreme Court, and now an assistant New York DA was telling him that he couldn’t get an adjournment in the Jefferson Market Courthouse unless some functionary from the vice society would allow it.

And Sumner refused. There had been at least six adjournments already, and he appeared in court for each one of them. The case should have been heard back in October, and now that it was February, he had run out of patience. Besides, Sumner told him, it was an open-and-shut case—it would be over as soon as the judges read the magazine. So Quinn was, more or less, forced to get a note from his doctor. He drew up an affidavit certifying his laryngitis in order to request an adjournment directly from the judge, and the court granted him ten more days.

Quinn told Anderson and Heap to start thinking about character witnesses, people who could vouch for their motives in order to limit the penalty. They were definitely going to be found guilty—“There isn’t the slightest shade of a doubt of that,” he told Anderson—and because they had a history of violations, they would be treated like “old and callous offenders.” They were lucky to be prosecuted under the state law, where the maximum penalty at the time was only a thousand-dollar fine and a year in prison. If they were luckier, their punishment might be a permanent postal ban. But if they were defiant in court, he said, they might go to prison.

Sumner’s prosecutions routinely put people behind bars, even when the offenders were more important than the Little Review editors. When he prosecuted the president of Harper & Brothers for publishing an obscene book earlier that year, the company’s president was ordered to pay a thousand dollars or spend three months in prison. Quinn might post fifty dollars in bail for Anderson and Heap, but he was not about to give them two thousand dollars for their freedom.

—

THE LITTLE REVIEW was inundated with angry letters about Ulysses. The editors generally ignored them, but one envelope featured such beautiful handwriting that Margaret Anderson opened it. A woman in Chicago wished to share her thoughts about Mr. Bloom’s encounter with Gerty on the beach:

Damnable, hellish filth from the gutter of a human mind born and bred in contamination. There are no words I know to describe, even vaguely, how disgusted I am; not with the mire of his effusion but with all those whose minds are so putrid that they dare allow such muck and sewage of the human mind to besmirch the world by repeating it—and in print, through which medium it may reach young minds. Oh my God, the horror of it . . . It has done something tragic to my illusions about America. How could you?

Anderson stayed awake all night trying to write an answer large enough to encompass her indignation over the writer’s “profound ignorance of all branches of art, science, life,” though in the end she could only be dismissive: “It is not important that you dislike James Joyce,” she wrote back. “He is not writing for you. He is writing for himself.”

Anderson courted hardship and ostracism partly, as Quinn suspected, for self-advertisement, but mostly because she saw it as the key to independence. Anderson broke away from her family only to find that she had shifted her dependence to contributors, advertisers, patrons and foreign editors. She envied the fact that people like James Joyce and Emma Goldman were in exile or in prison for something bigger than themselves. The image of Joyce toiling through war, illness and penury to follow his own vision—publishers, readers and puritanical policemen be damned—was, for Anderson, the essence of art. Now that she had criminal charges against her, she shared Joyce’s defiance and with it, she hoped, his independence. In the belated The Little Review issue following the charges, Anderson insisted that genuine art rested upon two principles: “First, the artist has no responsibility to the public whatever.” The public, in fact, was responsible to the artist. “Second,” she emphasized, “the position of the great artist is impregnable . . . You can no more limit his expression, patronizingly suggest that his genius present itself in channels personally pleasing to you, than you can eat the stars.”

The Little Review existed for genius—that was why Anderson and Heap “fought like devils” for every issue. Anderson wanted, as she later wrote to a friend, to be “the arranger of life, the killer of the philistine, the favorite enemy of the bourgeoisie.” Whereas Ezra Pound wanted an aristocracy of taste, Margaret Anderson wanted an autocracy, a society in which the exceptional would rule over the unexceptional. “Anything else,” she wrote, “means that the exceptional people must suffer with the average people—from the average people.” For Anderson, the obscenity trial against Ulysses and The Little Review was not a fight for the freedom of speech. It was a fight for the freedom of genius.