CHAPTER 10

The Art of Rainmaking

Stop going for the easy buck and start producing something with your life. Create, instead of living off the buying and selling of others.

—Carl Fox (in the movie Wall Street)

GIST

A Native American rainmaker is a medicine man who uses rituals and incantations to make it rain. For startups, a rainmaker is a person who generates large quantities of business. Like medicine men, entrepreneurs have created their own rituals and incantations to make it rain.

Two factors make rainmaking difficult for startups. First, although entrepreneurs design a product or service for a specific purpose, they have no way of knowing who will actually buy it and what it will be used for. Thus, the first step of rainmaking is to get version 1.0 of the product or service into the marketplace to find out where it blossoms. Keep your eyes open because you may find yourself in the midst of a gorilla market.

Second, the products and services of startups are rarely just bought. Instead, they must be sold because few customers want to take a chance on a new product or service from a small, undercapitalized organization. Thus, the second step of rainmaking is to overcome this resistance.

Before we begin, here’s a story that illustrates how an entrepreneur both found out who would buy her product and overcame resistance to stocking it. A Parisian store once rejected the newest fragrance of Estée Lauder, the famed purveyor of perfume. In anger, Lauder poured the fragrance all over the floor, and so many customers asked about it that the store had to carry it. Sometimes when it pours, it rains.*

LET ONE HUNDRED FLOWERS BLOSSOM

I stole this concept from Mao Tse-tung, although he didn’t exactly implement it during the Cultural Revolution. In the context of startups, the concept means

Sow many seeds. See what takes root and then blossoms. Nurture those markets.

Many companies freak out when they notice that unintended flowers have started blossoming. They react by trying to reposition their product or service so that the intended customers use it in intended ways. This is downright stupid—on a tactical level, take the money! When flowers are blossoming, your task is to see where and why they are blossoming and then adjust your business to reflect this information.

Here are three eye-opening examples of blossoming flowers cited by the dean of entrepreneurial writing, Peter F. Drucker:

- The inventor of Novocain intended it as a replacement for general anesthesia for doctors. Doctors, however, refused to use it and continued to rely upon traditional methods. Dentists, by contrast, quickly adopted it, so the inventor focused on this unforeseen market.

- Univac was the early leader in computers. However, it considered computers the tool of scientists, so it hesitated to sell its product to the business market. IBM, by contrast, wasn’t fixated on scientists and thus let its products blossom as business computers. This is why IBM is a household name, and you can only read about Univac in history books.

- An Indian company bought the license to manufacture a European bicycle with an auxiliary engine. The bicycle wasn’t successful, but the company noticed many orders for only the engine. Investigating this strange development, the company found out that the engine was being used to replace hand-operated pumps to irrigate fields. The company went on to sell millions of irrigation pumps.*

The following matrix shows a useful way to think of blossoming flowers. Most companies want to occupy the top left corner. The real action is in the bottom right corner, so be flexible and be open to unforeseen customers and uses.

| INTENDED CUSTOMER | UNINTENDED CUSTOMER |

Intended Use | Expected | Delightful (Example: car dealers—not only private owners—selling used cars on eBay) |

Unintended Use | Delightful (Example: women using Avon’s Skin So Soft as an insect repellent) | Astounding (Example: computer novices creating newsletters, magazines, and forms with Macintoshes) |

SEE THE GORILLA

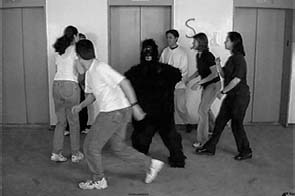

Daniel J. Simons of the University of Illinois and Christopher F. Chabris of Harvard University ran an interesting experiment that has rainmaking implications. They asked students to watch a video of two teams of players throwing basketballs to one another. The students’ task was to count how many passes one team made to their teammates.

Photo credit: A single frame from a video by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris. The video is available as a part of the Surprising Studies of Visual Awareness DVD from Viscog Productions, Inc. (www.viscog.com). Copyright 2003 by Daniel J. Simons. Used with permission.

Thirty-five seconds into the video, an actor dressed as a gorilla entered the room the players were in, thumped his chest, and remained in the video for another nine seconds. When asked, fifty percent of the students did not notice the gorilla!* Apparently, they were attending to the assigned task of counting passes and were perceptually blind to extraneous events.

The same phenomenon occurs in organizations: Everyone is focused on the intended customers and intended uses, and they fail to see flowers blossoming in unexpected ways. Univac, in the example cited previously, focused on the scientific market and failed to see the business market—unlike IBM. You must let a hundred flowers blossom and pick the unexpected ones—the gorilla markets in the midst, so to speak—to make it rain.

PICK THE RIGHT LEAD GENERATION METHOD

Many entrepreneurs, particularly ones with technical backgrounds, rely on traditional methods of generating sales leads, such as advertising and telemarketing. This reliance tends to be reinforced if managers with “proven backgrounds” from large companies join the team.

These methods might work if people bought the products and services of startups. However, recall that the products and services of startups are sold, not bought. For selling to work, entrepreneurs need to establish their credibility and develop face-to-face, personalized contact—an effort that begins with effective lead generation.

Henry DeVries of the New Client Marketing Institute investigated methods of generating leads. He found that the most effective technique was conducting small-scale seminars to introduce the product—not advertising, telemarketing, making glossy brochures, or exhibiting at trade shows. These are his top five methods:

- Conducting small-scale seminars

- Giving speeches

- Getting published

- Networking in a proactive way

- Participating in industry organizations

It’s risky to generalize his findings to every business, but they do contradict traditional thinking, and you should consider them when you’re trying to make it rain.

FIND THE KEY INFLUENCER

“Data base administrator III.” This sounds like an unlikely title for a decision maker. It conjures a picture of someone stuffed in a messy cubicle jammed full of technical manuals, eating Subway sandwiches for lunch.

Lisa Nirell was a rainmaker at BMC Software. One such data base administrator III (DBAIII) bought more than $400,000 worth of software from her company. Stuck in his cubicle, phone constantly ringing, this DBAIII influenced the major purchases for his company. When the executive vice president had questions about projects or vendors, it was Mr. DBAIII he visited.

The higher you go in big companies, the thinner the oxygen; and the thinner the oxygen, the more difficult it is to support intelligent life. Thus, intelligence is concentrated in the middles and bottoms of large companies. Here is a key insight for rainmakers:

Ignore titles and find the true key influencers.

Logically, the next question is “How do I find out who the key people are and get to them?” The answer is that you have to ask secretaries, administrative aides, and receptionists—which leads us to the next point: Suck down.

SUCK DOWN

I’ve made dozens of decisions about companies and people by consulting two terrific assistants at Apple and at Garage: Carol Ballard and Holly Lory. I would ask them such questions as “What do you think of that guy?” or “What do you think of this idea?” If their answers were “He’s a jerk,” “He’s rude,” “He’s an egomaniac,” or “It’s a dumb idea,” he or it was finished with us.

You may think it astounding that assistants had such power and influence with me—Surely Guy is the exception to the rule. In most cases, executives carefully consider every phone call, meeting, and e-mail and then tell an assistant what to do. Dream on. What I’ve described is how the world works.

Rainmaking requires access to your key influencers and decision makers. This includes face-to-face access, telephone access, or even e-mail access. Unfortunately, these kinds of people are bombarded by salespeople—every one of them with a “great” product or service. (No one ever calls to sell a piece of crap.)

Hence, many key influencers and decision makers employ people to shield them from rainmakers. Let’s call them “umbrellas.” To make it rain, you have to learn how to suck down to umbrellas. They are called secretaries, administrative aides, and sometimes even data base administrators III. Sucking up is vastly overrated—sucking up cannot work unless you first get through the phalanx of umbrellas, so read on to learn how to effectively suck down.

- UNDERSTAND THEM. You may think that their job is to prevent you from gaining access. Don’t flatter yourself. You’re not that important. Their job is to enable the executive to do his job—and one aspect of this is guarding his time (which many people, such as you, might waste).

- DON’T TRY TO BUY THEM. No one likes to be bought—or, more accurately, to be thought of as someone who could be bought—so don’t send gifts to bribe your way in. The way to get in is to have a credible introduction and a rock-solid proposition and then to treat every contact in the organization with respect and civility.

After you’ve had access (whether the access worked out or not), you can follow up with an e-mail, handwritten note, or gift. Sometimes the most effective follow-up is a photocopy of an article the umbrella would find interesting. Whatever you do, gratitude is always better than bribery. - EMPATHIZE WITH THEM. Odds are, this person isn’t making much money—certainly a pittance compared to the executive. And the umbrella could probably run the place better than the executive. Companies pay umbrellas small salaries, so don’t think they “should” take your abuse.

- NEVER COMPLAIN ABOUT THEM. Even if the umbrella is stone-cold wrong, never go over his head and complain. The first thing that will happen is that this complaint will circle back to the umbrella, and you can kiss your access goodbye. Forever.

GO AFTER AGNOSTICS, NOT ATHEISTS

[T]he defenders of traditional theory and procedure can almost always point to problems that its new rival has not solved but that for their view are no problems at all.*

One of the holy grails of rainmaking is landing “the reference account.” This is the big, prestigious account that provides wheelbarrows of money, plus credibility, too.

Back in the mid-eighties, the reference-account software companies for a new personal computer were Ashton-Tate (dBase) and Lotus Development (Lotus 123). Oh, to have their products run on Macintosh…it would establish Macintosh as viable. But it was not to be—and it didn’t matter.

By definition, reference accounts are already successful and established. Usually, they benefit from the perpetuation of the status quo. Herein lies the problem: If you have an innovative product or service, these accounts are the least likely to embrace it. They are atheists when it comes to a new religion because they are the high priests of an old order.

Unfortunately, many startup organizations obsess about landing these reference accounts—as Apple did with Ashton-Tate and Lotus. They will do almost anything to have them as customers because their presence is the equivalent of being blessed by the Pope.

Take it from someone who did it wrong: Ignore atheists. Look instead for agnostics—people who don’t deny your religion and who are at least willing to consider the existence of your product or service. If your dream reference account doesn’t “get it,” cut your losses and move on.

Agnostics, or “nonconsumers,”† typically aren’t using anything because of the high cost or skill requirements of the current offerings. For example, during the introductory phase of personal computers in the eighties, people couldn’t afford personal mainframes or minicomputers. Even if they could, these products were so hard to use that consumers wouldn’t have had the necessary skill level.

Thus, agnostics are easier to please than atheists because you’re enabling them to do something they simply could not do before—as opposed to having to displace an entrenched product or service. Apple seldom got people to switch from Windows (despite its ad campaign), but for people who had never used a personal computer before, Macintosh was life-changing.

Nothing should excite an entrepreneur more than penetrating a market full of agnostics.

MAKE PROSPECTS TALK

Nature, which gave us two eyes to see and two ears to hear, has given us but one tongue to speak.

If a sales prospect is willing to buy your product or service, he will often tell you what it will take to close the deal. All you have to do is shut up so your prospects can talk.

The process is simple: (a) create a comfortable environment by asking permission to ask questions, (b) ask questions, (c) listen to the answers, (d) take notes, and (e) explain how your product or service fills their needs—but only if it does. And yet many people fail at this:

- They are not prepared to ask good questions. It takes research before a meeting to understand a prospect. Furthermore, they are afraid that asking questions makes it look as if they don’t already know the answer.

- They can’t shut up because they belong to the bludgeon school of sales: I’ll keep talking until the prospect submits and agrees to buy. Or, they may be able to shut up, but then they don’t bother listening. (Hearing is involuntary; listening is not.)

- They don’t take notes because they are lazy or don’t consider the information important. Taking notes is a good idea, as mentioned in Chapter 7, “The Art of Raising Capital.” First, it will help you remember things. Second, it’s bound to impress the prospect that you care enough about what was said to write it down.

- They don’t know enough about their product or service to effectively apply it to the needs of prospects. This is inexcusable.

Let’s say that your product offers several different benefits (not features!) such as saving money, providing peace of mind, and enlightening people. Begin by mentioning all three benefits and let prospects react. They will typically tell you which of the benefits are appealing.

If nothing resonates, ask the prospect what would. From that point on, focus on what you just heard because the prospect has just offered you a valuable tidbit: “This is how to sell to me.” The point is to let the prospect talk, to listen, and then to be flexible. Remember: You’re selling, they aren’t necessarily buying. If a customer tells you how to sell to them, you damn well better listen.

ENABLE TEST DRIVES

The most difficult barrier that startups face is reliance on the status quo. Usually people think the old products and services are good enough: I can do everything I want to with my computer with a text-based interface. Why would I want a graphical user interface?

This doesn’t mean that every product in widespread use is good enough—only that customers have accepted them as such. Thus, an entrepreneur’s job is often to show people why they need something new. The traditional way to do this is to bludgeon them with advertising and promotion.

However, countless companies have already flooded the marketplace with the same claim: better, faster, cheaper! Also, as a new organization, you probably don’t have enough money to reach critical mass in advertising and promotion.

Thus, the best way for a startup to attract customers is to enable them to test drive its product or service. Basically, you are saying

- “We think you’re smart.” (This already sets you apart from most organizations.)

- “We won’t try to bludgeon you into becoming a customer.”

- “Please test drive our product or service.”

- “Then you decide.”

Test driving is different for every business. Here are some examples that illustrate widespread applicability:

- H. J. Heinz (2002 revenues of $9.4 billion) gave away samples of his pickles at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. His booth was stuck in a low-traffic location, so he hired kids to pass out tickets that promised a free souvenir for visiting his booth to get a pickle.*

- General Motors created the GM 24-Hour Test Drive program to enable people to take cars home for the evening in order to truly test drive them. This sure beats the usual car-dealership test drive of going around the block.

- Salesforce.com enabled people to use its software for a thirty-day period at no charge. The beauty of this test drive is that once you have this kind of information about a company’s product, you’re less likely to switch because of the data entry you’ve already done.

Suspend your dependence on traditional and expensive methods of marketing your product or service and give test driving a test drive. It’s the best way to overcome the status quo.

PROVIDE A SAFE, EASY FIRST STEP

One of the mistakes Apple made when we introduced Macintosh was that we asked information technology managers to throw out existing computers and replace them with Macintoshes. We were asking them to take a leap of faith. With hindsight, it should not have been surprising that few companies took us up on this request.

Mixing metaphors, if you want to make it rain, don’t try to boil the ocean. Instead, offer customers a smooth, gentle, and slippery adoption curve. This means asking customers to use your product or service in small pieces of the business, in a limited and low-risk manner:

- one geographic location, such as a regional office

- one department or function

- one project

- a brief trial period

- a simple act of support

Assuming that you do have a great product or service, simply getting in the door is the hardest part of the battle. If you’re lucky, your product or service will please the customer, and satisfaction will catalyze further adoption. It seldom goes this smoothly, however, because while getting it in is hard, getting it used is just as hard, as is getting it spread. But the process always starts with getting it in.

Counterintuitive as this may seem, you should also implement a safe, easy last step for customers—that is, to make it easy for customers to end their relationship with you. For example, Netflix, the DVD subscription service, has an easy and friendly five-minute process to end subscription to its service. It enables people to have a positive last experience with the company.

It’s far better for former customers to say, “Netflix wasn’t for me because I don’t watch that many DVDs,” than “It took me an hour on the phone and three months of fighting with my credit card company before I could unsubscribe. I will never use Netflix again.”

Furthermore, because of the good feelings that Netflix’s exit procedure generates, former customers are much more willing to reinstate their accounts when they receive Netflix’s friendly e-mails a few weeks later.

LEARN FROM REJECTION

If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the precipitate.

Rainmakers get rejected. In fact, the best rainmakers probably get rejected more often because they are making more pitches than others. However, a good rainmaker learns two lessons from rejection: first, how to improve his rainmaking; second, what kind of prospects to avoid. Here is a list of the most common rejections and what to learn from them:

- “YOU ARE NOT ONE OF US. STOP TRYING TO BE ONE OF US.” You typically encounter this rejection when you are trying to change fundamentally how something is done. For example, when Apple introduced the Macintosh, Apple attempted (and failed) to gain acceptance by selling Macintoshes to information technology departments. When people tell you this, go around or under them. For example, selling Macintoshes to the graphics department worked for Apple.

- “YOU DON’T HAVE YOUR ACT TOGETHER.” One of two things happened: Either you really didn’t have your act together or you stepped on someone’s toes. Force yourself to review your pitch and interpersonal skills to determine if it’s the former. If you stepped on someone’s toes, figure out how to make amends.

- “YOU ARE INCOMPREHENSIBLE.” You usually hear this when you are, in fact, incomprehensible. Go back to the basics: Cut out the jargon, redo your pitch from scratch, and practice your pitch. The burden of proof is upon you—if you need to find a customer who’s “smart enough to understand why they need our product,” you’re going to starve to death.

- “YOU ARE ASKING US TO CHANGE, AND WE DON’T WANT TO HEAR THIS.” This is a common response when presenting to a successful group that is living the high life and sees no reason to change. What you’re hearing is that you’re in the right market but talking to the wrong customers, so look for customers who are feeling pain.

- “YOU ARE A SOLUTION LOOKING FOR A PROBLEM.” This means that you are still inside your value proposition looking out. The appropriate response is to keep permutating your value proposition until you are outside the value proposition (like customers) and looking in. If you can’t get on the outside, let’s face it: You may, in fact, be a solution looking for a problem.

- “WE’VE DECIDED TO STANDARDIZE ON ANOTHER PRODUCT (OR SERVICE).” You’re probably trying to sell to the wrong person if you hear this and your product or service is truly, demonstrably better. Avoid the gatekeeper and find the user. Do what you have to do to get an entrée to the final customer. If your product or service isn’t truly, demonstrably better, maybe the final customer told the gatekeeper to get rid of you.

MANAGE THE RAINMAKING PROCESS

Rainmaking is a process, not a one-time event or an act of God. You can’t abdicate it to some “sales types” or to sheer luck. It is a process; you can manage it like other processes in your organization. Here are some tips for how to do this:

- ENCOURAGE EVERYONE TO MAKE IT RAIN. Someday you may reach the point where your engineers and inventors can simply toss a new product or service over the cubicle wall and have the salespeople pick it up and sell it. But that day isn’t here yet.

- SET GOALS FOR SPECIFIC ACCOUNTS: when you expect them to close, and how much each sale will yield on a weekly, monthly, and quarterly basis.

- TRACK LEADING INDICATORS. Everyone has trailing indicators, such as the previous month’s and quarter’s sales. Leading indicators, such as the number of new product ideas, cold calls, or sales leads, are important, too. It’s easy to know where you’ve been—it’s harder and more valuable to know where you’re going.

- RECOGNIZE AND REWARD TRUE ACHIEVEMENTS. Don’t allow rainmakers to submit intentionally low forecasts so that they can easily beat them. Certainly don’t recognize and reward intentions—intentions are easy, rainmaking is hard.

If you don’t manage the rainmaking process, you’ll start with “Our projections are conservative,” and six months later, you’ll be saying, “Our sales are coming in slower than expected.” There is nothing sadder.

FAQ

Q. Where would I find the early adopters and risk takers in large companies?

A. It’s difficult to provide a general answer to this question. It’s easier to tell you where you probably won’t find these types of people: at the highest levels. So let a hundred flowers blossom inside these companies—don’t go in with preconceived notions of who the early adopters are.

Q. We have the opportunity to hire a rainmaker, but he wants significant stock options, plus $150,000 per year, plus another $75,000 in expense accounts. That’s in addition to our trade show and advertising budget. He’s got a good reputation and accounted for $16 million per year in sales in his previous job and says this will be a big step down in terms of income. Why should we hire him rather than going with manufacturers’ representatives?

A. Rainmakers are expensive, but if they can deliver, they’re worth it. If he wants the world—and it sounds like that’s the case in this scenario—make him earn it with a compensation plan dependent upon results. I wouldn’t simply give him everything he wants at the start.

RECOMMENDED READING

Cialdini, Robert. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. New York: Morrow, 1993.

Coleman, Robert E. The Master Plan of Evangelism. Grand Rapids, MI: Spire Books, 1994.

Moore, Geoffrey. Crossing the Chasm: Marketing and Selling High-Tech Products to Mainstream Customers. New York: Harper Business, 1999.