The history of the persecution of Jews in the Vaucluse has remained hidden for decades in the confines the synagogue and the Jewish cemetery of St. Roch in Avignon; places that are almost exclusively visited by Jews. The Jews feared that a simple public reference to past abuse would be construed by the “others” as an accusation and an indictment. It is what many young Jews growing up in Vaucluse experienced immediately after the war. That issue had to be forgotten once and for all.

In fact, this was the general consensus, and certainly that of Michel Hayez, the director of the archives of the département of Vaucluse, when he essentially told the author, at the beginning of 1992: “There is no need to look at the archives. The history of Vaucluse during Second World War has already been written. Why don’t you read the book by Aimé Autrand instead? He provided the lists of all the deportees.”

Aimé Autrand, the Vaucluse representative in the Committee for the History of Second World War, presided over by Henri Michel, had been designated to provide the official view of those events. In his 1965 book, Autrand published the “authorized list” of victims, amongst them “82 racial arrestees.”1 This Vaucluse list, which is unbelievably short, will in turn be sanctioned by Henri Michel’s Committee as an official component of the national synthesis. The significant errors and omissions in the list of the Vaucluse originate mostly from methodological flaws. The basic documents are incomplete, and in particular, the lists of arrests made directly under German control, as acknowledged by Autrand himself.

… However, in the absence of any police report on this topic (and for a good reason) we could unfortunately not indicate (even approximately) the number of people arrested and directly taken to the German prison after these operations…2

To establish his “authorized list” of those arrested and deported, Autrand did not use sources external to the Vaucluse, which could have filled the gaps and provided additional names. To be fair, it must be said that some of these sources were not readily available in the sixties as they are today, such as the data bases of Yad Vashem3 and of the Centre de documentation juive contemporaine (CDJC).4 However, most of the archives of the Vaucluse municipalities, rich in detail, as shown by Michèle Bitton and Jean Priol for the deportees of Pertuis5 and Villelaure,6 and by Bruno Tognarelli7 for the children of the Vaucluse, were ignored by Autrand.

Since Aimé Autrand did reconstruct his lists in part by using testimonies and statements from survivors, some errors are directly linked to new arrivals from other départements, and to the absence of testimony about some deportees. This explains the presence in his book of people who had resided in other départements during the war, as well as the absence of the names of some victims of the Vaucluse, because no witness came forward on their behalf.

These factors alone resulted in the omission of more than 220 victims. But there is a far more serious historical shortcoming, which attests to multiple breaks of professional ethics: the hundred or so foreign Jews deported during the summer of 1942 are not documented anywhere. Yet, it was Autrand himself who had organized their deportation in August 1942.8 He was at the time the Head of Division in charge of Police Affairs, Weapons, Foreigners and Jews, a position he held at the Prefecture of the Vaucluse from July 1940 to September 1943.

These arrests were made following orders of Pierre Laval and took place all across the free zone with the support of the Gendarmerie. On August 24, 1942, the prefect of the Vaucluse wrote:

As a follow up to the conversation you had this morning with the competent division Head in my prefecture and with the General Secretary, I am honored to request that you order the arrest on Wednesday 26 of the current month starting at dawn,* of all the foreign Jews on the list attached.

These individuals will have to be assembled in the nearest barracks and taken to the “camp of les Milles” near Aix-en Provence with two buses which I will make available to that effect and that will arrive at 7 a.m. that day in front of the Avignon city hall.

The list in question is that of the Jews of the Vaucluse who had entered France after New Year’s Day 1936; it includes 110 people.9

The “competent division Head” is no other that Aimé Autrand himself, and in fact, he is the author of this letter in the name of the prefect, as attested by the letterhead label D1 B2.* Several months later, the Rapides du Sud Est bus company will remind Autrand that he still owes them some 2,866.50 francs for this “transport of August 26 to the camp of les Milles.”

It is, to say the least, a strange omission for a man who had himself been at the center of these arrests. His services had even prepared the list. One could begin to see a few “explanations.” “Oh, come on, Monsieur Levendel, these people were not his Jews,” an archive employee had suggested in 1992. One can “understand”—the people deported in August 1942 were not “the Jews of Aimé Autrand.” Many of them were indeed refugees in the Vaucluse. To be “a Jew of Autrand,” one had to be a French Jew or to have arrived in the Vaucluse before January 1, 1936, according to Vichy’s criteria. So be it!

This explanation is however not very convincing, when one sees that Aimé Autrand had published the name of Simon Ebstein who was on the victims’ list provided to the Gendarmerie on August 24, 1942. Simon Ebstein, who was to be arrested two days later, escaped and was picked up a few weeks later near the Swiss border; yet he was not “a Jew of Autrand.” In fact, the most probable explanation for the omission is that Autrand had not wanted to give to the Committee of History of the Second World War the list of his own victims. Remorse? Embarrassment? Fear of the consequences? It is also possible that the committee of Henri Michel was not that interested in the list of the Jewish victims of 1942.

Robert Bailly, the other historical icon of Avignon, provides an answer for both himself and his illustrious predecessor, Aimé Autrand. First, the deportation of Jews rates only a few words in his book about Avignon. In addition, on the page he dedicated to the Gestapo, Bailly sympathizes with Autrand.

It is not appropriate for us to mention here its activities [the Gestapo], the time has not yet come! In addition, as written so well by Aimé Autrand: “It is better not to mention these things, so as not to run the risk of awakening resentments which have not been completely forgotten…”* It should be added that many of the actors of some dramas are still around amongst us.10

So, now we know. These “historians” have no business in the actual history of the Vaucluse. Their main aim is to boost the prestige of the département without making too many waves. If one was not aware of the exceptional work of some historians, this could cast a shadow on the entire profession.

Vichy had been planning the measures against the foreign Jews long before August 1942. On March 25, the regional director of the CGQJ had forwarded to the regional chief of Police for Jewish Affairs the following report provided a few days earlier by Henri de Camaret, delegate of the CGQJ for the Vaucluse.

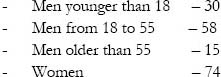

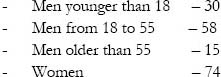

SUBJECT: Census of the Jews who had entered France since January 1, 1936 In the Vaucluse: 177 were counted as follows:

As a matter of course, the commission for the enlistment of foreign workers in Avignon has already enlisted 24 of those who currently hold a job in a profession useful to the National Economy—particularly in agriculture…

The delegate for the Département of the Vaucluse H. de Camaret11

The date of entry in France, mentioned in this letter of March 25, 1942, strangely coincides with the cutoff date for the deportees of August 26, 1942, which implies that this deportation had been planned for a long time. But this also reveals a discrepancy. Why did Henri de Camaret gather the names of 177 people in this category, while Autrand only uses 110 of them—a difference of 67 individuals? This difference can be explained—but only in part—by the 24 foreign Jews enlisted “as a matter of course” by the commission for the enlistment of foreign workers. (Incidentally, this commission was presided by no other than Aimé Autrand himself.) In the end, at least 43 Jews—some of them arrested after August 26 and not accounted for—seem to have slipped through the cooperation between Autrand and de Camaret. Could it then be that Autrand had dragged his feet?

There is an irony in the description of his own role during the war by Autrand, the delegate of the Vaucluse in Henri Michel’s committee.

Autrand Aimé, born on April 11, 1892, in Camaret (Vaucluse). Head of a division in the cabinet of the Prefect of the Vaucluse in November 1940, when the purges were decided by the Vichy government. With three or four of his colleagues at the Prefecture, he was to become the targeted victim, under the pretext “that he had served the republican regime too loyally” (this was, at least literally, the reason invoked in the report which Special police superintendant Nouvet had addressed to the Prefect of the Vaucluse on November 10, 1940). If he was not fired (as the new leaders of the Légion des Combattants demanded), it is because the new Prefect, air force general Louis Valin, a high government officer of exceptional probity, deemed that under these circumstances, it would be sufficient for the head of the division to be “moved away” from the cabinet of the Prefect. In exchange, he entrusted him with the management of police affairs, including: control of foreigners, Jews and weapons. This was indeed a particularly thankless administrative attribution…12

Aimé Autrand almost succeeds in making us lose sight of who the victims were.

This text however still holds a residual ambiguity: Autrand does not state his own title. The answer is provided by a fanatic of the new regime, Jacques Petit, the president, for the Vaucluse, of l’Amicale de France:

M. Autrand had been named head of division. But the Prefecture, being of the third class, was supposed to have only two divisions instead of the four that had been created to “find a spot” for friends. M. Autrand had to be demoted to the rank of department head. However, it seems that, in spite of it, he has kept his salary level and his mail signature delegation.

This sectarian officer and staunch supporter of the Front Populaire was chosen by Prefect Valin to establish the political files of the officer of the département [of the Vaucluse].

This nomination, extraordinary to say the least, was made with full knowledge of the facts by M. Valin, who had made a point to please senator [Ulysse] Fabre, a friend of [Edouard] Daladier, and M. Gonnet, who states everywhere that, although a strong supporter of the Front Populaire, he is strongly backed, in Vichy, by a high ranking officer of the Ministry of the Interior.13

This makes Autrand’s position look like a pro forma demotion since he kept his salary and several functions were still under his authority. In fact, he used the label D1 B2* while dealing with Jewish affairs.

This note confirms what has been known from other sources. Before the war, Autrand had been a radical socialiste close to Edouard Daladier, who was mayor of Avignon before moving up to the national scene and becoming prime minister. He was an “enlightened” member of the Vaucluse establishment and showed no sympathy for fascism. His political circle included people on the left. Some, like Jean Garcin, later chose to resist. After the 1940 defeat, Joseph Cucumel, a resistance member from the beginning, in charge of infiltrating public administration in the Vaucluse, had criticized Autrand for staying on within the administration of Vichy.14

This raises a fundamental ethical question. Were Autrand and the prefecture aware, between 1940 and 1942, of the seriousness of their actions against the Jews? This can be placed on two levels: that of systematic discrimination—census, spoliation, house arrests, professional destitution—and that of pure and simple deportation, as in August 1942. On the first level, how could Autrand accept the blacklisting of human beings protected by the fundamental principles at the heart of the Republic? How could he justify it? Were the moral standards of that period so different from ours? And if that had been the case, why did others make very different choices?

On the second level, did Autrand and his peers know—even vaguely—the consequences of the deportations they had carried out in August 1942? On September 12, 1942, the department of foreigners and police affairs of Autrand had intercepted a letter of Léon Rosenthal, the shoemaker of rue Joseph Vernet. This document, addressed to the office of l’Œuvre du secours aux enfants in Montpellier, speaks volumes on the question.

To the Union O.S.E.

It is in the name of a desperate mother whose husband has just died that I appeal to you. It is about saving the lives of two children, one five and a half years old and the other seven; as well as their mother, Mrs. Régine Bobryker, all interned in the Camp of Les Milles. I beg you to intervene urgently; because we are talking about human beings and above all children.* I am sending you my last cry of desperation. Be merciful. This cry is of a dying woman. Save the two children and react urgently… Save them immediately. Take pity on these children lives.15

What this letter does not mention is that the father, Joseph Bobryker, was in fact alive. He was not arrested, because he was not sleeping at home, like many others at the time. So far, only men had been targeted for deportation. But, aware of the danger after the arrest of his wife and children, he behaved discreetly. Léon Rosenthal, the intermediary and a communist, was a reliable source of information circulating amongst the members of the communist party.16 The two children, Norbert and Rachel, will be saved by the OSE; they now live in Australia. It appears that at least a few Jews were keeping their eyes and ears open. One can understand the blindness of some. But how is it possible that the police services of Autrand and the Renseignements généraux had no knowledge of this information?

The “Non Crime” of August 1942

Autrand was not indicted at the Liberation for what he had done during the war, in spite of the fact that he had presided over anti-Jewish measures as early as November 1940. Actually he would return to the prefecture as a head of division, a position that he had de facto occupied during the war. “Apparently, no charges were filed against him,” said Joseph Cucumel, secretary of the Prefecture after Liberation, who was aware of Autrand’s collaboration with Vichy, as we noted earlier.17 This is confirmed by Maxime Fischer, a refugee from Paris who became a resistant, co-founder of Maquis-Ventoux and sub-prefect in charge of the purges for a few months after Liberation. He explained: “How was I supposed to know, if nobody complained about it?”18

An important event contributed to covering up Autrand’s responsibility in the deportation of Jews in 1942. His arrest for supporting de Gaulle on September 16, 1943, along with 123 others from the Vaucluse, in the vast political crackdown organized by the Germans with the participation of the Milice and the Groupes mobiles de Réserve. That roundup was meant in part at shaking the inertia and the passive resistance of the administration toward the designs of the German occupying forces. Six days later, on September 22, 1943, Autrand forwarded to prefect Georges Darbou a letter written in pencil on a few pages torn out of a notebook.

You have surely been informed, Mr. Prefect, that I was arrested last Thursday by units of the German police.

I have not worried until now, because I thought that this was a general security measure taken against some categories of French people, or that I had been the victim of an error and that I would soon be freed.

If I am taking the liberty of writing to you today, it is to protest vehemently to you regarding my complete innocence.

I give my word as a family man that I have never done nor attempted nor conceived anything against the operational authorities [the Germans].

Also, I am awaiting with confidence, but also with the impatience that you can imagine, the moment of my interrogation so that I may justify myself.

I assure you, Mr. Prefect, of my respectful devotion and my loyal commitment to my duties.19

These few lines did not have the desired effect, and despite everything, he was sent to a labor camp in Linz, Austria. He was released for health reasons before the end of the war and repatriated to Avignon. Obviously, the arrest reflected a change of mind on his part, but it also came as convenient protection when he returned from captivity.

Aimé Autrand later was co-opted as a representative of the Vaucluse in the Comité pour l’histoire de la seconde guerre mondiale despite his antecedents, that Henri Michel knew about thanks to Robert O. Paxton.20 There was a document concerning Autrand available to the public at the CDJC concerning his role at the Prefecture of Vaucluse. “One can expect from M. Autrand a good collaboration,” a visitor from Vichy had reported in 1941 regarding the census of the Jews delivered by Autrand.21

Paradoxically, the fox was set to mind the geese, and in his capacity as an official historian of the Vaucluse, he was granted free access to the archives documenting his own misdeeds, while the law hampered the steps of most other “innocent” researchers.

How many people in the know have remained silent, or kept their voices too low to be heard, or saw nothing wrong with the deportations, all along? Would it have been the same if Aimé Autrand had organized the deportation of resistance fighters? The answer can be found in the trial of the prefect of the neighboring Gard département, Angelo Chiappe, sentenced to death on December 21, 1944, for collaboration and intelligence with the enemy, and executed one month later. The charges against Chiappe included belonging to the Group Collaboration, his active support for the milice, and his zeal in increasing the enrollment for the STO (Compulsory Labor Service). But the heaviest element of all—the one that cost him his life—was a list of 50 hostages* he had provided to the Germans, following a bombing, where five Germans soldiers and two French women lost their lives at the “Maison Caro,” a brothel reserved for the German army. Although Chiappe had also organized the roundup of Jews in 1942 in step with the other prefects of the free zone, that charge was not brought against him.22 Just as in the trials of Marshal Philippe Pétain23 and Pierre Laval,24 the persecution of the Jews was seldom explicitly taken into account in the indictments of individuals who operated in the Vaucluse. This was a recurring pattern in the trial files at the base of our work, even when the testimonies spoke to the contrary. Masking the impact of the Holocaust was not an accident, and seemed to result from a convergence of several interests, a kind of implicit consensus between various segments of society.

Let us now turn to the way Autrand describes the role he played during the war in his own words:

Thanks to the kindness of the population, and the “complicity” of the competent service of the Prefecture, numerous Jews worthy of interest were able to elude, for a few months, the zealous inspectors of the CGQJ of Vichy, but this was to change starting in 1943, when many miliciens or members of the PPF were able to obtain their addresses.25

First, Autrand informs us that the “competent service of the Prefecture”—a bureaucratic euphemism to designate the service that he managed—had snatched “numerous Jews worthy of interest” from the clutches of “the zealous inspectors of the CGQJ of Vichy.” Of course, we know the fate of the other Jews—those who had not been “worthy of interest”—arrested during the operations which Autrand himself had organized in August 1942. All were deported in convoys 29 to 33 and murdered, with the single exception of Icek Agjengold from Villelaure, who survived Auschwitz and returned without his wife and two children.

Autrand also gave the impression that the arrests of Jews in 1942 were the doings of the “zealous inspectors of the CGQJ of Vichy,” while he concentrated on saving a few victims of choice. The truth is sadly different.

Two questions still remain. The first relates to historical fact: what was the true nature of the relations between Autrand and those “zealous inspectors of the CGQJ of Vichy”? The second has to do with the addresses of the Jews which “numerous miliciens or members of the PPF were able to obtain.” How did these addresses find their way into the “wrong hands”?

The Accomplices

The deportations of 1942 were exclusively organized by the Vichy government in the free zone, and Autrand was not the sole “contributor” to this operation for the Vaucluse. It began with the measures against the Jews promulgated by Vichy including the census managed by Autrand with the assistance of the municipalities. The conspiracy continued with house arrests or internment in the GTE by the head of the division, Aimé Autrand. This made it easier to find the foreign Jews when the time came.

Of course, all those actions were covered by the prefects succeeding one another in Avignon: Louis Valin from September 1940 to November 30, 1941, Henri Piton from December 1, 1941, to March 15, 1943, Georges Darbou from March 16, 1943, to December 15, 1943—later as the representative of the prefects of the free zone to Pierre Laval—and Jean Benedetti from December 16, 1943, until his arrest on May 11, 1944. Every one of them countersigned the measures against the Jews. Even though Benedetti was considered a friend by the CDL (Committee of Liberation), this does not change the fact that the last census of the Jews of May 1944 was prepared under his authority. Apparently, in those days, one could at the same time make a list of Jews and remain a friend of the Resistance.

Torpedoing the hunt for the Jews was not in the radar screen of the Resistance of the Vaucluse. In 1994, Maxime Fischer was asked why his network did not attack a German deportation train that was forced by the allied bombardments to stop for more than 24 hours in Sorgues (Vaucluse) on August 18, 1944. His answer was simple: “I had only about 80 men at my disposal in the entire département; nobody had informed me about the deportation train, and even if I had known, the allies had not provided us with any heavy weaponry for fear of a communist takeover; our limited individual weapons were no match for the heavily armed German detachment on the train.”26 Also in 1994, while explaining his role in fighting the Germans, Jean Garcin, the former head of the Groupes Francs* for the R2 région (Vaucluse, Bouches-du-Rhône, Gard, Var, Basses-Alpes and Alpes-Maritimes), mentions several daring operations to free “comrades” from the hands of Germans in Marseille. “M. Garcin, did you organize any action to free Jews?” He gives a simple and eloquent answer: “We were fighting the common enemy.”27

On the allied side, all the way to the top, the “Jewish issue” did not weigh much. Even the word “Jew” is strangely absent from a 39 page study of the BBC and the propaganda war in occupied France.28 “Anti-Semitism” appears only once. In a cooperative publication, Sébastien Laurent poses a simple quandary “The French Military Secret Services and the Holocaust, 1940–1945: Omission, Blindness, or Failure?”29 The answer may lie in a conversation between two men specialized in the French sector: on January 2, 1943, Peter Storrs (Special Operations Executive) spoke with Lewis Gielgud (Political Warfare Executive). In the eyes of Storrs, emphasizing the persecution of the Jews was counterproductive:

In conversation with two young Frenchmen who have just arrived in this country after doing good work for us in France, I learn that the continued reference in BBC broadcasts to the persecution of the Jews tends to be resented by the French, who themselves have so many relatives imprisoned in German prison camps or concentration camps.30

Silence during the war and silence after the war.

The deportations of August 1942 were prepared and executed at the direction of Prefect Henri Piton, a long-time official at the ministry of Interior. In 1943, Piton moved on under Max Bonnafous, Secretary of State for agriculture and food supply, and after the Liberation, he resurfaced as Prefect of the département of Maine et Loire, a position he held from May 11, 1945, until his retirement the following year. The change of heart of the prefecture after the German invasion served as a screen for others besides Autrand.

One must not forget the denouncers of all sides, and in particular, the representative of the CGQJ, Henri de Camaret, who made it his duty and was often too pleased to reveal how the Jews avoided the census.

A close accomplice of Autrand, Tainturier, the commander of the Gendarmerie of the Vaucluse, put together the detailed logistics of the arrests carried out on August 26, 1942. He was also responsible for the transfers before that date of the Jews assigned to the GTE under his control. On August 26, 1942, Tainturier dispatched his gendarmes to the towns and villages of the Vaucluse to “collect” the foreign Jews. A multitude of reports written on the same day bear witness to the systematic effort invested in the operation. Captain Ferrier, commander of the Gendarmerie Section of Orange gave an account of his action in Orange, Sablet, Bollène, Valréas et Vaison.

The collection operations of the foreign Jews in the list attached to note Nr. 1704 from the Prefect dated August 24, 1942, began on August 26, 1942, at daybreak and went off without any major incident.

His team did not let go of its victims easily.

After arriving at 4:15 a.m. at the home of the family of Osias Tieder in Sablet, the gendarmes could not get any answer to their calls. At 5:15 a.m., they had to seek the mayor who had to call a locksmith to open the door. The bedrooms and attic were searched to no avail. They discovered the husband hidden behind the door of the basement, the wife Brucha Tieder was lying in a corner, entirely hidden under a pile of garbage.

Brucha and Osias perished in Auschwitz. Absent from home, their three children, Ida, Martin and Sarah, were saved. The gendarmes probably could have listened to their conscience and discreetly sabotaged the orders of Tainturier. They are not the only ones who did not do so. For instance, two gendarmes of Bollène had visited the Sapirs, their friends, on the evening of August 25, 1942, to have an aperitif, as usual. They could have warned them, allowing them to flee, but they did not and they returned the next day at dawn to arrest the family.31 The Sapirs (the mother, Szayne, and her children, Estelle and Yehuda) and the sisters Margolis (Estéra and Rose) who lived with them owed their lives to the presence of mind of Szayne and to the help of two doctors, Basch and Descalopoulos. Indeed, Estéra Margolis was declared unfit to travel by the two doctors following an appendectomy that was completely healed. As to Szayne Sapir, Captain Ferrier wrote:

The woman named Szayne Sapir had a strong fit of hysterics upon the arrival of the gendarmes, and it became necessary to call a doctor who stated that her transport was impossible.

Marianne Basch, the doctor in question, had helped Mrs. Sapir by finding that she suffered from several fictitious “ailments.” During her fit, Szayne was muttering unintelligible words, but in fact, she was warning her family in Yiddish, thus allowing them to flee through a back window. Ferrier concluded:

Out of 14 people targeted in this residence [Bollène], only 9 could be arrested.

Apparently, there were not enough merciful acts as remarkable as those of the two doctors, since the gendarmerie of the Vaucluse could claim approximately one hundred arrests of Jews who were unable to find help.

To our knowledge, no one was ever brought to trial for the action of August 1942 against the foreign Jews of the Vaucluse (or any other département of the free zone for that matter). It was a crime that did not exist in the eyes of Justice.

As to Marianne Basch, harassed by Jean Lebon, the SEC delegate for the Vaucluse, and targeted by the German police, she was finally forced to flee for her life in early December 1943; since her husband, lieutenant Georges Basch,* dead in June 1940, was Jewish, so were her two children, André and Françoise.

Full Circle

In the CDL meeting of October 11, 1944, the President, Paul Faraud, informs the committee: “I have received a request from M. Autrand, head of Division and President of the purge committee of the Prefecture, a request expressing his desire to obtain access to M. Pleindoux’ file…”32 The CDL which had already examined the Pleindoux case does not deem it necessary to transfer the file. In the session of January 12, 1945, André Genin, a former member of the Resistance who takes over the coordination of the purges, pays tribute to the work of his predecessor, Maxime Fischer, “in particular in the management of the purges, the relations with the FFI,* and the advocacy for the Resistance before the Prefecture.” He underscores that Fischer has worked under appalling conditions, and he adds: “From now on, it is M. the Prefect who will rule on the files I will bring before him. M. Autrand has accepted to assist me on a voluntary basis.”

Aimé Autrand has come full circle to respectability. First, he is appointed to supervise the purges in the Prefecture staff. Then, he volunteers to help M. Genin in ridding all Vaucluse of collaborators.

To complete the circle, Michel Hayez, the retired director of the archives départementales de Vaucluse, informs us that a street has been named in honor of Aimé Autrand.

Since December 21, 1990, a stone’s throw from St. Joseph church, Aimé Autrand (1892–1980) and Robert Bailly (1922–1988) each has his own place. Aimé Autrand, an officer of the Prefecture, cultivated the taste of archives to the point that, after his retirement, he took on the job of classifying and filing those of the city [Avignon]; in addition to various studies related to the département, his work, le Département de Vaucluse de la Défaite à la Libération† (1965), stands out in the field…33

Of course, Michel Hayez keeps from mentioning Autrand’s burdensome past which he knew well and had “laundered” for the occasion.34 It would be more fitting to remove the street plate with the name of the man in charge of the “collection” of the 1942 deportees, and find, instead, a street name commemorating the victims.

____________________

* The sender had underlined two important elements

* The prefecture is composed of divisions supervised by the prefect and his secretary. Each division includes several bureau (departments). Autrand was the head of Division D1, Bureau (department) B2.

* Bold in the original text.

* 1st Division, 2nd Department (Bureau).

* Underlined in the police report and possibly in the original letter of Rosenthal.

* The 50 hostages were released after the discovery of the authors of the bombing.

* The Groupes Francs (Free Groups) were a segment of the Resistance movement.

* Georges Basch was the son of Victor Basch, the president of the Ligue of Human Rights, and his wife Hélène. Both his parents were assassinated on January 10, 1944, by members of the Milice under direct supervision of Paul Touvier.

* French Forces of the Interior, name used by de Gaulle toward the end of the war to designate the diverse body of Resistance fighters. The FFI would be incorporated in the regular army as early as October 1944.

† The département of Vaucluse from Defeat to Liberation