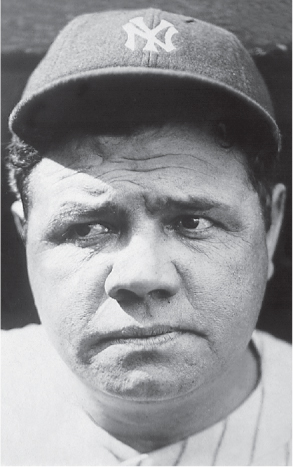

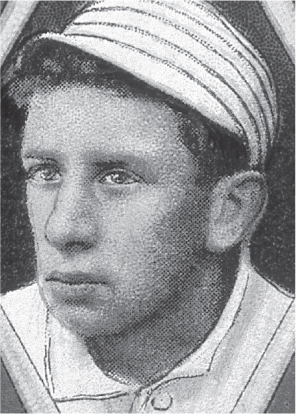

#1 George Herman “Babe” Ruth

P-OF-1B, Red Sox, Yankees, Braves, 1914–35.

Hall of Fame, 1936

It’s been almost 100 years since the world first heard of George Herman Ruth. In that time, there have been a lot of great players. But over that 100-year span, it’s hard to argue that the man his teammates called “Jidge” isn’t still the greatest.

He started his baseball career as a left-handed catcher for the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys. He was, in the words of one of his later teammates, Harry Hooper, a “green pea,” fresh off the streets of Baltimore. At St. Mary’s, Ruth was introduced to baseball, which gave him focus and structure. Since he was a big kid, he was a catcher at first and, on occasion, he pitched. Eventually, his coach at St. Mary’s decided the big fellow was better on the mound than behind the plate.

Ruth was eventually signed by the Baltimore Orioles at the time a successful minor league club. On one of his first days with the team, one of the veterans asked another who the new kid was. Oh, said the other vet, that’s [manager] Jack Dunn’s “baby.” A nickname was born.

He was a great pitcher for the Orioles. Signed by the Red Sox in 1914, he became a star in his second season. By 1915, he was arguably the best left-handed pitcher in the American League. His duels with the Senators’ Walter Johnson are considered classics.

That 1915 season was the first time he ever hit a home run, a mighty blast off New York pitcher Jack Warhop on May 5. He found he enjoyed it.

In 1920, the Red Sox sold Ruth to the New York Yankees. That trade may have been the most significant in baseball history. It marked the end of the Boston dynasty (four World Series wins in the decade) and the beginning of Yankee greatness.

The Yankees converted one of the best pitchers in baseball to an outfielder, a ridiculous concept even now. But of course, it worked. In 1921, he hit 59 home runs, more than every other team in the league. In 1927, he hit 60, still one of the top seasons in baseball history.

He was stylish, he was colorful. In 1930, Ruth signed for $80,000 per year, a figure that brought his annual salary to $5,000 more than President Herbert Hoover. A reporter asked Ruth how he could justify making more than the president of the United States of America.

“Well,” said Ruth, “I had a better year than he did.”

His pitching and hitting records have, for the most part, been broken over the last few decades. But his legacy as baseball’s star of stars endures.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .342, HR: 714, RBI: 2,213, H: 2,873, SB: 123. W: 95, L: 46, SV: 4, ERA: 2.28, SO: 488, CG: 107

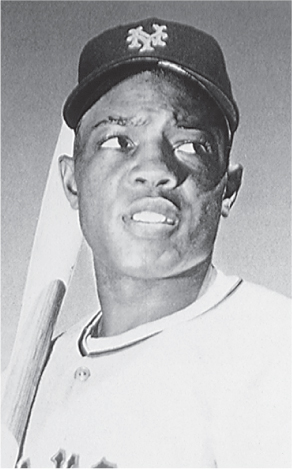

#2 Willie Howard “Say Hey Kid” Mays

OF-1B, Giants, Mets, 1951–73. Hall of Fame, 1979

Speed (led the NL in stolen bases four consecutive years). Power (second player in baseball history to hit 600 home runs, ending up with 660). Durability (20 consecutive All-Star Game appearances).

In Willie Mays’ case the numbers shout for themselves: This is an all-time great.

Mays was a star in the Negro Leagues for a few years, before being signed by the New York Giants. His first year in the Big Apple was 1951, the year the Giants edged the Dodgers for the National League crown. Mays, in fact, was in the on-deck circle when the Giants’ Bobby Thomson hit his historic home run. Mays won 11 Gold Glove Awards. His most famous defensive play came in the 1954 World Series, off Cleveland’s Vic Wertz. Wertz ripped a deep fly ball to center field. Mays turned and ran full speed to the center field wall, and caught the ball over his shoulder, a feat that is still seen on replays.

When appraised of the play, Mays was always quick to point out that the reason the catch was so vital was that he also had to make a throw afterwards, as there were less than two outs, with men on base.

Mays won MVP awards in 1954 and 1965. There are at least three other years in which his statistics are comparable to or better than those years, but the fact is, baseball writers were always uneasy awarding to many MVP awards to one player.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .302, HR: 660, RBI: 1,903, H: 3,283, SB: 338

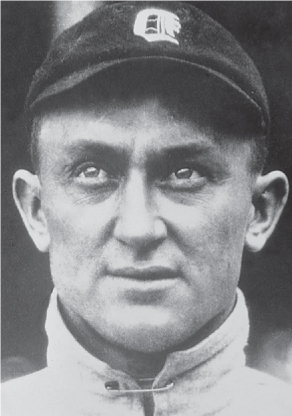

#3 Johannes Peter “Honus” Wagner

SS-OF-1B-3B, Louisville, Pirates, 1897–1917. Hall of Fame, 1936

The story goes that one day in Pittsburgh, Wagner was manning his shortstop position when he reached around with his glove hand to pull out a chaw of tobacco from his back pocket. (In the early days of baseball, players wore gloves that more closely resembled golf gloves.) The batter hit a sharp grounder his way. Wagner calmly bare-handed the ball and gunned it over to first, thus throwing out a man with one hand behind his back.

Wagner was stocky, barrel-chested and had shovels for hands. Legend has it that when he dug balls out of the infield dirt and zipped them over to first base, a small load of stones and dirt would travel with the ball.

He played virtually every position except catcher. He was a tremendous hitter, winning eight batting titles and six slugging average titles. He hit over .300 16 times, led the league in doubles seven times and triples three times. He stole 722 bases, and led the league in that category five times.

In 1902, Wagner played 61 games in the outfield, 44 at shortstop, 32 games at first base, one at second base and pitched once. He didn’t make an error at any of those positions. From 1913 to 1916, he led the league’s shortstops in fielding position.

Wagner was a terrific athlete: He may well have been the first baseball player to lift weights, and he was a fanatic about a new game that had recently been invented in Springfield called basketball. He played baseball until he was 43 and was perhaps the best 40-year-old player in baseball history.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .327, HR: 101, RBI: 1,732, H: 3,415, SB: 722

#4 Tyrus Raymond “Ty” Cobb

OF-1B, Tigers, A’s, 1905–28. Hall of Fame, 1936

Seventy-five years after he retired from baseball, Ty Cobb still owns the best career batting average of all time: .366. And he still holds the distinction of being the nastiest SOB of all time. There are no stats for that; Cobb has retired the trait.

Be that as it may, the man could hit: a total of 12 batting championships, including five in a row from 1911 to 1915. He had back-to-back .400 seasons in 1911 and 1912, with another .400 season in 1922, and more than 4,100 career hits, a record that stood for 50 years.

Cobb wasn’t a slugger in the present sense of the word, but he still had a career slugging percentage of .512, and led the league in that category eight times.

And he could run: 892 stolen bases, leading the league six times. He was the all-time leader until Lou Brock passed him in 1978.

Was he mean? Yeah, he was mean. He used to sharpen his spikes in the dugout as opposing teams took batting practice, and he wasn’t afraid to jab a slow-footed infielder when sliding into second or third base. He had more than his share of fights, and in 1912, went into the stands after a heckling fan.

He’s known to have cheated. According to pitcher Dutch Leonard, he paid off Cleveland’s Tris Speaker and Joe Wood to throw a game to the Tigers so Detroit could finish third. He may have tried to fix other games, but it was impossible to determine.

Cobb, were he alive today, would probably say that he played to win, at any cost. He did. And it paid off. In 1936, he was the top vote-getter for the first class of the Baseball Hall of Fame, topping Babe Ruth, Cy Young and Honus Wagner.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .366, HR: 117, RBI: 1,937, H: 4,189, SB: 892

#5 Walter “The Big Train,” “Barney” Johnson

RHP, Senators, 1907–27. Hall of Fame, 1936

Johnson was a 6'1" strikeout machine, an affable soul who could buzz a baseball from the mound to home plate as fast as anyone in history.

It was, at least partly, the arms. Johnson had long, limber arms, and he threw the ball with an easy sidearm motion that arrived in his catcher’s mitt with a sound like a rifle shot.

Johnson played his entire career with the Washington Senators, an organization not particularly known for its acumen. With Johnson leading the way, the Senators did manage a pair of World Series appearances, and in 1924, he was a world champion.

The story of that final game is one of the fine yarns of World Series play. Johnson pitched four innings of scoreless relief in Game Seven after pitching a complete game two days earlier. Teammate Early McNeely’s 12th-inning seeing-eye single scored the winning run.

Johnson was the Sultan of Strikeouts, to borrow a nickname from his contemporary, Babe Ruth. The Big Train (so named for the locomotive-like velocity of his pitches) led the league in strikeouts 12 times, in shutouts seven times, in wins and complete games six times and in ERA five times.

Johnson won 417 games and saved 34 more for the Senators.

He was as affable as Ty Cobb was rambunctious. Old-timers swore that when Johnson was far ahead in a game, he would ease up on a rookie or former teammate and let them get a hit. It’s probably true.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 417, L: 279, SV: 34, ERA: 2.17, SO: 3,509, CG: 531

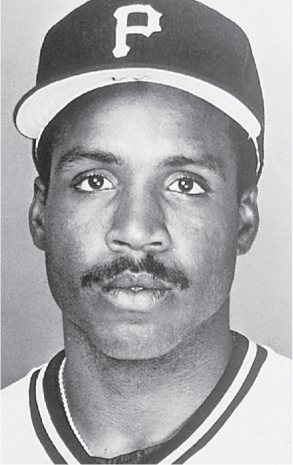

#6 Barry Lamar Bonds

OF, Pirates, Giants, 1986–2007

The new home run king, Bonds is one of the greatest offensive performers in baseball history. The 14-time All Star has been the Most Valuable Player of the National League seven times, in 1990, 1992, 1993, 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004. In three of those years, he was voted the Player of the Year in the Major Leagues.

Throughout most of his career, Bonds has never been far from the top. He was the runner-up to the National League MVP award twice, in 1991 and 2000. In 1994, he was fourth in the voting, and in 1996 and 1997, he was fifth.

Bonds is the all-time leader in walks, with 2,515; second in career extra-base hits, with 1,425; third in career runs scored, with 2,198; fourth in career total bases, with 5,906; and third in RBI, with 1,996. Heck, he’s even 32nd on the stolen-base list, with 514. In the field, Bonds has won eight Gold Gloves.

If there is a knock on Bonds, statistically, it’s that his postseason work has not been as stellar. His teams, the Pirates and the Giants, have made it to the postseason nine times, winning only two series, in 2002, when San Francisco defeated Atlanta and St. Louis before falling to the Angels in the World Series.

Bonds has batted .245 in postseason play, with nine homers and 24 RBI. His best three series were in 2002, when he hit .294 with three home runs against the Braves in the Divisional Series, .273 with six RBI against the Cardinals in the Championship Series and a stellar .471 in his only trip to the World Series.

On Nov. 15, 2007, Bonds was indicted by a federal grand jury for allegedly lying to another grand jury in 2003 about his use of performance-enhancing steroids. Bonds pled not guilty to four counts of perjury and one count of obstruction of justice. His trial is expected to start sometime in late 2008. His adherents will say, this is a player who stands above all others of his generation. His detractors will say the numbers are artificial. But Bonds is clearly the greatest player of his time, steroids or no steroids.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .298, HR: 762, RBI: 1,996, H: 2,935, SB: 514

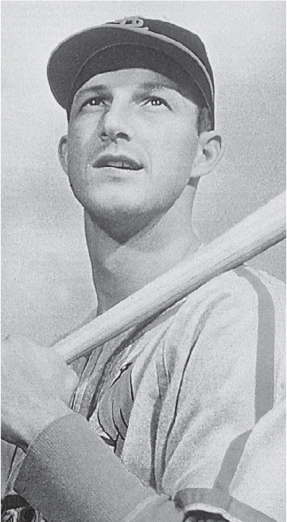

#7 Mickey “The Commerce Comet” Mantle

OF-1B-SS, Yankees, 1951–68. Hall of Fame, 1974

Mantle was a man blessed with thunderous home run power and blazing speed. He was named after Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane, and he was even better than Cochrane.

Where to start? He was a switch-hitter who hit 536 home runs: 373 from the left side of the plate, 163 from the right. With his great upper body strength, some of those home runs were monster shots, like the one on May 22, 1963, which almost carried out of Yankee Stadium.

But he was also a tremendous bunter and base stealer. Mantle stole 153 bases, including 21 in 1959. He was only caught stealing three times that year. With his speed, he also hit 72 career triples, leading the league with 11 in 1955.

Mantle, a 16-time All Star, won the Triple Crown in 1956, with 52 home runs, 130 RBI and a .353 batting average. He won the MVP award that year, as well as in 1957 and 1962. He also won a Gold Glove in 1962. He was as fast afield as he was on the base paths, and had a rocket arm.

He was a clutch player, who regularly played in pain. He was also a great teammate who befriended rookies and marginal players throughout his career. He was a leader on the Yankees and a huge fan favorite throughout his career.

He may have hung in with the Yankees a few years too long, at least by some folks’ standards. But let’s face it: The Mick loved the game, and it was hard to let go.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .298, HR: 536, RBI: 1,509, H: 2,415, SB: 153

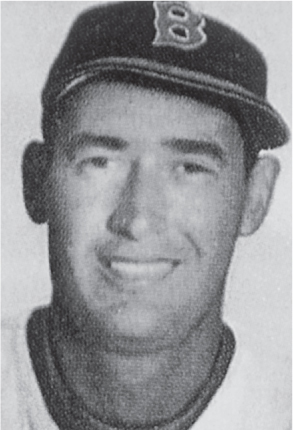

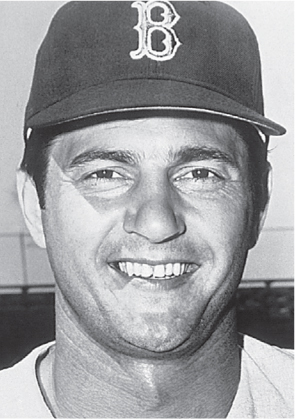

#8 Theodore Samuel “Ted,” “Teddy Ballgame,” “The Kid,” “The Splendid Splinter,” “The Thumper” Williams

OF, Red Sox, 1939–42, 1946–60. Hall of Fame, 1966

It is hard to believe that Ted Williams, a man who was so much larger than life, is no longer with us. We want him to be like those actors on the silver screen: undaunted, immortal, unconquerable.

He wanted to be known as the greatest hitter who ever lived. He might have been. He didn’t hit for as much power as Babe Ruth (although he lost four years to two wars, and still hit 521 homers). He didn’t make as many hits as Ty Cobb (although his career on-base percentage is almost 50 points higher: .482 to .433).

Five times in his career, in fact, Williams had an on-base percentage of .500 or better. The year he hit .406, it was .553, a record at the time. That meant that 55 percent of the time, when Williams came to bat, he at least made it to first base. He was as nearly unstoppable as a player could be.

He played hard every game. He played on great Red Sox teams in the late 1940s, and he played on awful Red Sox teams in the 1950s. He hit .406 in 1941, two numbers every baseball fan worth his salt knows. He hit .400 two other times, albeit in shortened seasons: In 1952 he hit .400 in the first six games of the season and went back into the service to fight in the Korean War. He came back from that war late in 1953 and hit .407.

He was an authentic American hero who fought in World War II and the Korean conflict. His plane was shot down in the Korean War and he almost died. But Williams didn’t want to sit on an Army base and play on a club team: He wanted to be where the action was.

He won six batting titles, two MVP awards, four home run crowns, a Triple Crown in 1942 and was a 17-time All Star. He was a great player. When he was elected to the Hall of Fame, he used his acceptance speech to lobby for the great players of the Negro Leagues to be inducted. And soon, of course, they were.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .344, HR: 521, RBI: 1,839, H: 2,654, SB: 24

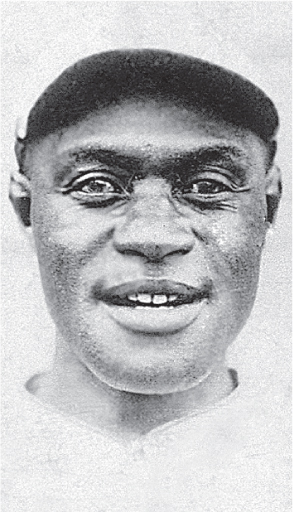

#9 Joshua “Josh” Gibson

C, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords (Negro Leagues), 1929–46. Hall of Fame, 1972

He was a stellar player in a legendary league. He was Josh Gibson, “the Black Babe Ruth,” the greatest catcher of all time, the best position player in Negro League history.

His numbers are stratospheric. He is credited with 962 home runs over his long career, although there were several years in which he played a Negro League season and then headed south and played in either the Dominican League or the Mexican League. Still, 962 home runs are 962 home runs. Author John Holway’s statistical analysis of the Negro Leagues credits Gibson with 224 in Negro League play.

He is credited with 84 homers in 170 games in 1936, which includes non–Negro League contests. He hit 75 homers in 1931 and 69 in 1934. He is credited with hitting a ball nearly out of Yankee Stadium when the Grays played an exhibition game there one year.

His .351 batting average in Negro League play is the third-highest of all time. Gibson would routinely hit .400 or better in winter league play. In 1937, Gibson hit .479 in the Puerto Rican League. He was elected to nine Negro League All Star teams, where he hit an amazing .483 in All Star contests.

Defensively, Gibson was extremely quick, with a rifle arm. He was also a good base runner, and exceptionally fast for a catcher.

Gibson was a big man, at 6'1", 210 pounds. His easygoing nature was often interpreted as ignorance or low intelligence by writers and even fellow Negro League players. But it’s hard to believe a dumb guy could be such a great player.

In 1943, Gibson suffered a nervous breakdown, and his skills eroded quickly after that. He had begun to drink and probably also took drugs. He was still a good player for the next few years, but he was no longer the greatest. Early in 1947, he suffered a fatal stroke.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .351, HR: 224, H: 1,010

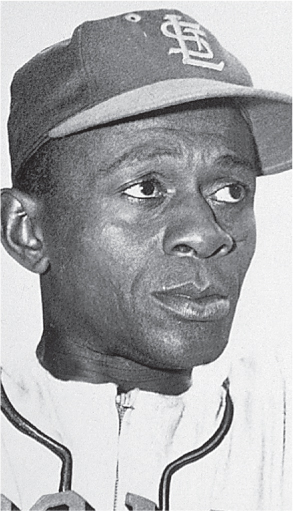

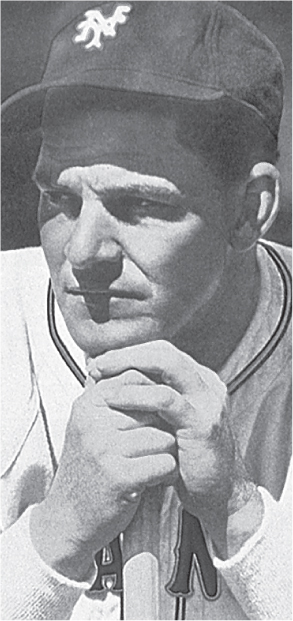

#10 Stanley Frank “Stan the Man” Musial

OF-1B, Cardinals, 1941–63. Hall of Fame, 1969

Consistency, durability and affability were the hallmarks of this man, the greatest player in a storied St. Louis Cardinal history.

In fact, the consistency of Stan the Man was taken to an amazing extreme: Musial had 1,815 hits at home and 1,815 on the road. He scored 1,949 runs and drove in 1,951.

His nickname, “Stan the Man” was a token of respect, bestowed on him by awed Dodger fans in the 1940s, as Musial led the Cardinals to four pennants in five years from 1942 to 1946. Musial, like the vast majority of his fellow ballplayers, didn’t play in 1945, as he was in the Navy.

Dodger hurler Preacher Roe summed up his pitching strategy against Musial succinctly: “Throw him four wide ones and try to pick him off first base.” Roe was only half kidding.

Musial was a hittin’ fool. He won seven batting titles, and led the league in hits six times, doubles eight times, triples five times, RBI twice, slugging percentage six times and walks once. In 1948, he missed the Triple Crown by a single home run. He was MVP three times and finished second four other times.

He was a 20-time All Star, and he probably should have made the All Star team in 1942, when he hit .315 with 32 doubles and led the Cardinals to a stunning five-game upset of the New York Yankees in the World Series.

He was a man who understood the gift he had, and appreciated it deeply. He never questioned umpires’ decisions and always seemed to enjoy the game.

He played in St. Louis for 22 years, and following his stint as a player, worked in the Card front office for another 25. After his career, the city erected a statue of Musial outside Busch Stadium. It was the least they could do.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .331, HR: 475, RBI: 1,951, H: 3,630, SB: 78

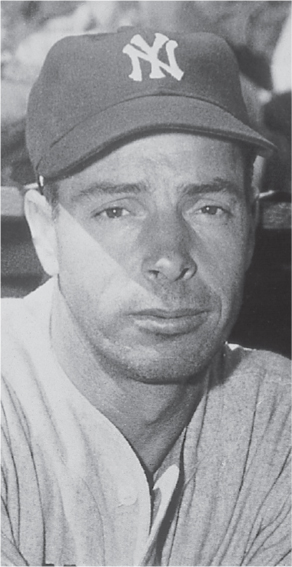

#11 Joseph Paul “The Yankee Clipper,” “Joltin’ Joe” DiMaggio

OF, Yankees, 1936–51. Hall of Fame, 1955

Joe DiMaggio might have been the best ballplayer ever, and the reason he isn’t farther up the list has more to do with the era than the man.

There is no way to measure what might be called the “woulda, shoulda, coulda” factor in sports. In this case, there is no way to determine how much his three-year participation in World War II affected Joe DiMaggio’s stats.

Put it this way: It didn’t help. Joltin’ Joe went into the service at 28 and came out when he was 31. He was an MVP twice before he went into the service, in 1939 and 1941, and once after, in 1947. He won two batting titles, both prior to 1942, in 1939 and 1940. In short, before Hitler shouldered his way into the equation, DiMaggio had a heck of a run.

And let’s face it, he still put up numbers. His 56-game hitting streak in 1941 is the one record that we’d be hard-pressed to see exceeded in the modern era. His .325 lifetime batting average is 41st all-time. Four times in his career, in 1937, 1939, 1940 and 1948, he had more RBI than games played.

He almost never struck out. For his career, DiMaggio whiffed 369 times, which is 2,228 times fewer than Reggie Jackson.

In the field, he saved the Yankees a lot of money in dry-cleaning bills. He was almost never out of position, so rare is the old-time Yankee fan who can recall DiMaggio ever having to make a diving catch or a lunging grab. He was always right there when the ball was hit to him.

DiMaggio didn’t really glide; former teammates recall a guy who ran like a buffalo in the outfield, with a thundering step and a good amount of huffing and puffing. But that was only close up. Watching from the stands, Joe made it look easy.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .325, HR: 361, RBI: 1,537, H: 2,214, SB: 30

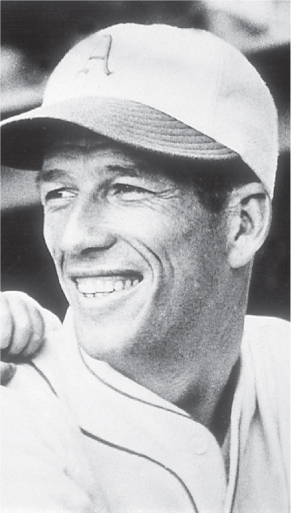

#12 Tristam E. “Tris,” “The Grey Eagle,” “Spoke” Speaker

OF-1B, Red Sox, Indians, Senators, A’s, 1907–28. Hall of Fame, 1937

Tris Speaker was the best two-way player of his generation. He was not as great a hitter as Ty Cobb, but was a better defensive player by miles and miles and a better teammate by a greater margin than that.

Speaker lived a legendary life. He broke his right arm as a youngster, so he learned to hit and throw left-handed. He started out as a pitcher. Scouts were interested, but his mother refused to sign his contract (Speaker was only 17), believing that buying and selling players was an insult. She eventually came around.

After he signed his first professional contract, Speaker hopped a freight car to the minor league town he signed with to save money. Speaker arrived literally an hour before the game and was told by his manager he was the starting pitcher. He lost the game, 2–1.

He was eventually converted into an outfielder but the Red Sox thought so little of him, they didn’t send him a contract the year after he signed. He reported anyway. The Sox still didn’t want him and left him behind in spring training, as payment to the Little Rock minor league team for the use of their ball field. He stuck around and dominated the Southern League. The Sox finally decided they liked him and brought him up in 1907.

He was a great hitter, winning the batting crown in 1916, and hitting .345 lifetime.

But he was an unearthly fielder. Blessed with great speed, he played the shallowest center field anyone could remember. Several times in his career, he completed unassisted double plays—that is, he would catch a line drive and run over second base to double up the runner. Amazing. He remains, 66 years after his retirement, the all-time baseball leader in double plays by an outfielder (139), as well as assists (449).

And he was a winner, with two world championships in Boston and the first-ever title in Cleveland in 1920.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .345, HR: 117, RBI: 1,529, H: 3,514, SB: 432

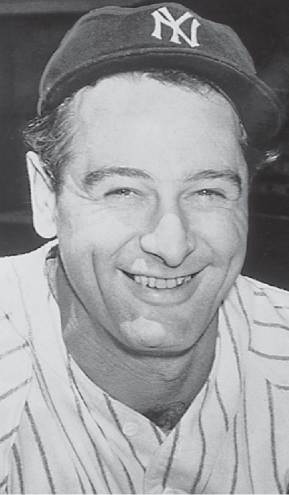

#13 Louis Henry “The Iron Horse” Gehrig

1B, Yankees, 1923–39. Hall of Fame, 1939

Lou Gehrig was the best first baseman, ever. A couple players come close, including Jimmie Foxx and, in the modern era, Mark McGwire. But neither can really match Gehrig’s tremendous production, year after year after year.

The story of how Gehrig began his amazing longevity streak of 2,130 consecutive games has, in the 21st century, undergone several permutations. He did replace Wally Pipp on May 31, 1925, and Pipp did indeed have a headache. But manager Miller Huggins didn’t exactly hand the position to Gehrig after Pipp sat out. Huggins pinch-hit for Lou several times in June and, in fact, Gehrig did not start at first base for New York on July 5 of that year (Pipp did), but got in for a couple of innings late in the game.

But Lou was hitting well and Pipp wasn’t, so Huggins left him in the rest of the year. And, of course, the year after that and the year after that, and, you get the idea.

Gehrig hit for average and he hit for power. He won three home run crowns, in 1931, 1934, and 1936. In that 1934 season, he won the Triple Crown with a .363 batting average, 49 homers and 165 RBI. He was MVP in 1927 and 1936.

Huggins used to say he thought Gehrig was actually a more dangerous hitter than Babe Ruth because he could use more of the field than Ruth. Gehrig also tended to hit line drives, which scared the hell out of his opponents.

In 1939, his health began to fail. Rumors abounded, and he finally traveled west to the Mayo Clinic. The diagnosis was almost too cruel to believe: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, to be known forever after as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

Gehrig was fading so fast, that Lou Gehrig Day was held on July 4, 1939. It is the most famous ceremony in baseball history, with Gehrig declaring, “Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” Maybe he was. He died two years later.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .340, HR: 493, RBI: 1,995, H: 2,721, SB: 102

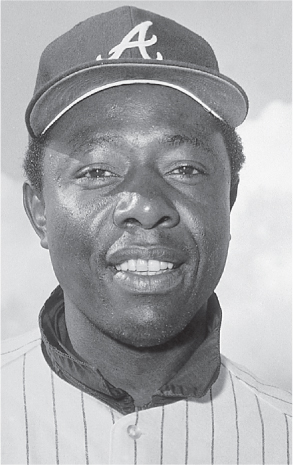

#14 Henry Louis “The Hammer” Aaron

OF-1B-DH, Braves, Brewers, 1954–76. Hall of Fame, 1982

The first name in baseball, literally. Aaron’s name is the opening entry in the baseball encyclopedia, and that is somehow fitting.

A self-effacing star who was, except for perhaps Lou Gehrig, the most stunningly consistent player ever, Aaron showed emotion only once on the field: when he cried after he broke Babe Ruth’s home run record. On April 8, 1974, against the Los Angeles Dodgers in Atlanta, Aaron belted a pitch from Al Downing over the left-field fence into the Braves’ bullpen to give him 715 career home runs, one more than Ruth.

Those tears were probably at least partly of relief. It may have been 1974, but this was still Atlanta, the heartland of the South, and Henry Aaron was a black man trying to outdo a white man, who was the all-time baseball legend, to boot.

Aaron’s performance under such conditions—he and his family received an incredible amount of hate mail—was remarkable. After hitting number 715, Aaron continued to play for two more years after 1974, and finally ended up with 755 for his career.

His consistency was numbing. Twenty-three consecutive years hitting 10 or more home runs, leading the league four times. Twenty-two consecutive years with 10 or more doubles, leading the league four times. Twenty-one years with more than 100 hits, twice leading the league. He was named to the All Star team 21 consecutive times. He went 14 years hitting over .300, winning batting crowns in 1956 and 1959. He garnered three consecutive Gold Gloves. And how about this? He went nine straight years stealing 15 or more bases. Not too shabby.

Aaron remains baseball’s top home run hitter, and the top man in RBI, total bases and extra base hits.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .305, HR: 755, RBI: 2,297, H: 3,771, SB: 240

#15 Robert Moses “Lefty” Grove

LHP, A’s, Red Sox, 1925–41. Hall of Fame, 1947

For most of his career, Lefty Grove was a surly SOB. He had a sizzling fastball and a temper to match it.

Maybe it was because the big left-hander didn’t get a chance to pitch in the big leagues until he was 25. He starred for the Baltimore Orioles, then a minor league squad, in the early 1920s, helping them win several International League championships.

Grove was finally sold to the Philadelphia A’s for $100,600 in 1920. That was more than the $100,000 fee the Yankees paid for Babe Ruth.

Grove was worth every penny—eventually. He was a tremendous pitcher as a rookie, leading the league in both strikeouts (116) and walks (131) in 1925. He ended up 10–12 that year, his only losing record in the major leagues.

By 1927, Grove was still blowing fastballs by hitters, and his placement was improving, as well. He struck out a league-high 174 batters and walked only 79. Grove would lead the league in strikeouts seven consecutive years while with Philadelphia.

In 1931, Grove went 31–4, with 27 complete games and four shutouts, both league highs. He also struck out a league-best 175 batters and won the ERA crown with a 2.06 mark. It was his best year.

Grove won nine ERA titles in his career. No other pitcher to date has won more than six.

For whatever reason, Grove didn’t hesitate to brush back, or hit, batters. He often scowled at teammates who made a bad play behind him.

In 1934, Grove was traded to the Boston Red Sox, who hoped Lefty could anchor a staff that would win a World Series. That didn’t happen, mostly because Grove sustained an injury to his left shoulder that dropped him to 8–8 that year.

But Grove was smart as well as talented. He was no longer a power pitcher, but he relied on guile and a good slider to win games now. He won 17 or more games three times with Boston, including a 20–12 mark in 1935.

Grove staggered to the finish line in 1941, going 7–7 and winning his 300th and last game. He retired to his home town of Lonaconing, Maryland, and opened a bowling alley.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 300, L: 141, SV: 55, ERA: 3.06, SO: 2,266, CG: 298

#16 Grover Cleveland “Pete” Alexander

RHP, Phillies, Cubs, Cardinals, 1911–30. Hall of Fame, 1938

Grover Cleveland Alexander is remembered, when he is remembered at all, as the guy who pitched drunk in the 1926 World Series. It’s an unfortunate distinction, because Alexander was one of the greatest pitchers in the history of the game.

He had an amazing rookie season, leading the league in wins (28), complete games (31), shutouts (seven) and innings pitched (367). Four of those shutouts were consecutive, including a 1–0 win over Cy Young, then in his final season.

He was a workhorse for the Phillies, leading them to the National League championship in 1915. That season, Alexander led the National League in wins (31), complete games (36), shutouts (12), innings pitched (376 1/3), strikeouts (241) and ERA (1.22).

That was a great year for “Old Pete,” as he was called then, but it was about routine for Alexander, who led the league in wins, strikeouts and complete games six times each, shutouts and innings pitched seven times each and ERA five times. From 1915 to 1920, six years in a row, Alexander’s ERA was below 2.00.

He did it with a rising fastball that he could throw at several different velocities, and a great, looping curveball that he could throw for strikes at any point in the count. He almost never walked anyone and he usually pitched very well in big games.

That was why the St. Louis Cardinals picked him up in midseason in 1926. Alexander won nine games down the stretch for St. Louis, propelling the National Leaguers into the World Series against the powerful Yankees.

Alexander had pitched a masterful Game Six in Yankee Stadium that year, winning 10–2, and figured he wouldn’t have to worry about appearing in Game Seven. Which is why he was in Billy LaHiff’s tavern in Manhattan the night before that final game. He closed LaHiff’s and missed batting practice the next afternoon.

In the bottom of the seventh, the Cardinals were ahead, 3–2, but the bases were loaded. So was Alexander, but he got future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri on knee-high fastballs to get him out and pitched two more scoreless innings for the win.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 373, L: 208, SV: 32, ERA: 2.56, SO: 2,198, CG: 437

#17 Robert LeRoy “Satchel” Paige

RHP, Birmingham Barons, Baltimore Black Sox, Cleveland Cubs, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Kansas City Monarchs, New York Black Yankees, Satchel Paige’s All Stars, Memphis Red Sox, Philadelphia Stars (Negro Leagues), Cleveland Indians, St. Louis Browns, Kansas City Royals, 1926–65. Hall of Fame, 1971

Satchel Paige was one of the few legends who might have been better than some of the stories told about him. A Negro League mainstay from 1926 until 1946, Paige was a gangly man who threw a blistering fastball for most of his career.

And the stories are true. He once walked the bases loaded with no outs and struck out the side (although it was in a semipro tournament). Several times, he would call in his outfielders and pitch to an opponent, again always in exhibitions or semipro games.

Once, in a tournament in Denver in the 1930s, Paige called in his outfielders and struck out the first two batters. The third batter slapped a soft fly ball to center field that would have easily been caught had there been anyone out there to catch it. The batter raced around the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

Paige estimated that in his total career, which often included playing exhibitions and playing in several leagues in one year, he pitched in 2,600 games, won 1,800, and threw 300 shutouts and 55 no-hitters.

Paige didn’t like his nickname much. He earned it when, as a young boy, he tried to steal a satchel from a man at a train station. He was caught and cuffed in front of his friends, who gleefully gave him the name. Over the years, he made up several more colorful stories that better fit his status as a great pitcher.

His frequent pay disputes with the various managers of teams in the Negro Leagues caused Paige to jump teams on an almost annual basis. In 1938, he was banned from the Negro National League, so he formed his own independent team, Satchel Paige’s All Stars, which easily outdrew other Negro League franchises. Paige was readmitted the next year.

In addition to his fastball, Paige had tremendous control and, like former Red Sox great Luis Tiant, possessed a variety of windups to deliver the baseball. In 1948, he was signed by the Cleveland Indians and went 6–1 as Cleveland won the world championship. He played for several more years before retiring to semipro teams and exhibitions. In 1965, he returned to the bigs, pitching three scoreless innings for the Kansas City Royals to become, at age 59, the oldest pitcher ever in the majors. It was one last story for the legend.

LIFETIME STATS: (MAJOR LEAGUES) W: 28, L: 31, SV: 32, ERA: 3.29, SO: 288, CG: 7. (NEGRO LEAGUES) W: 142, L: 92

#18 Edward Trowbridge “Cocky” Collins Sr.

2B, A’s, White Sox, 1906–30. Hall of Fame, 1939

At 5'9", 175 pounds, Collins wasn’t much to look at, but he was the most durable and consistent second baseman in baseball history.

Collins began with the Philadelphia A’s, and was the lynchpin of A’s manager Connie Mack’s “$100,000 infield” along with Stuffy McInnis at first base, Jack Barry at shortstop and Frank “Home Run” Baker at third. The $100,000 figure was the combined salaries of the four men in 1910. That is a little less than Alex Rodriguez makes a game, these days.

Collins was an excellent hitter who hit better than .300 a total of 19 times in a 25-year career. He led the league in runs scored three times and had 160 or more hits in 17 seasons.

He was also a great base runner, leading the league in stolen bases four times. As a fielder, Collins led American League second basemen in fielding nine times. Collins remains baseball’s all-time leader in assists with 7,630 and is second all-time in putouts with 6,526. There was simply nothing he did not do well.

Collins loved playing with the A’s, but his trade to the Chicago White Sox was, initially, something he looked forward to too. Mack was dismantling the A’s to reduce his payroll, and Collins did not want to be a part of a losing franchise.

He led the White Sox to the 1917 world championship, hitting .409 in the World Series. After a stint in the Marines during World War I, Collins returned to the White Sox to find a group of very talented players who hated skinflint owner Charles Comisky.

That White Sox team was, according to Collins, the most talented he played on. But their desire to make money “on the side” by throwing the World Series and betting against themselves horrified Collins. He did not participate and was one of the few starters of that infamous “Black Sox” team not banned from baseball.

Collins survived the scandal, and went on to manage Chicago and later become general manager of the Boston Red Sox.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .333, HR: 47, RBI: 1,300, H: 3,315, SB: 744

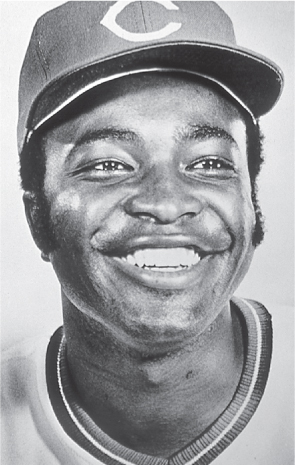

#19 Joe Leonard Morgan

2B, Astros, Reds, Giants, Phillies, A’s, 1963–84. Hall of Fame, 1990

Compact and powerful, Joe Morgan was the National League’s greatest second baseman.

Morgan broke in with the Houston Astros and played nine years in the Astrodome, making two All Star teams. He was traded to Cincinnati and developed into a superstar. Morgan was one of the keys to the Cincinnati “Big Red Machine” of 1972–76. The Reds won three National League pennants in that span, and back-to-back World Series in 1975 and 1976.

Not coincidentally, Morgan picked up a pair of MVP awards in that span, as well. Morgan is the only second baseman in baseball history to win consecutive MVPs.

An extremely patient hitter, Morgan led the National League in walks four times, and eight times in his career walked more than 100 times a year. He also led the league in on-base percentage four times.

Known for the distinctive flapping motion of his back elbow in the batter’s box, Morgan had very good power for a second baseman, hitting 27 home runs in 1976 and becoming that year only the fifth second baseman in major league history to drive in more than 100 runs with 111 RBI.

He was also an exceptional base stealer, swiping 20 or more bases 14 times in his career.

But beyond his stats, Morgan was a winner. He hit the game-winning single in the 10th inning in Game Three against the Red Sox in the 1975 World Series. And in Game Seven, he struck again, dropping in an RBI single in the top of the ninth to give the Reds the championship. Against the Yankees in the 1976 World Series, he hit .333 in a four-game sweep.

In 1980, Morgan was traded back to Houston, and helped the Astros win the division title. After a two-year stint with the Giants, he signed with the Phillies in 1983 and helped that team get into the World Series. Morgan led the team with five hits and two home runs, but the Phillies lost to the Baltimore Orioles in five games.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .271, HR: 268, RBI: 1,133, H: 2,517, SB: 689

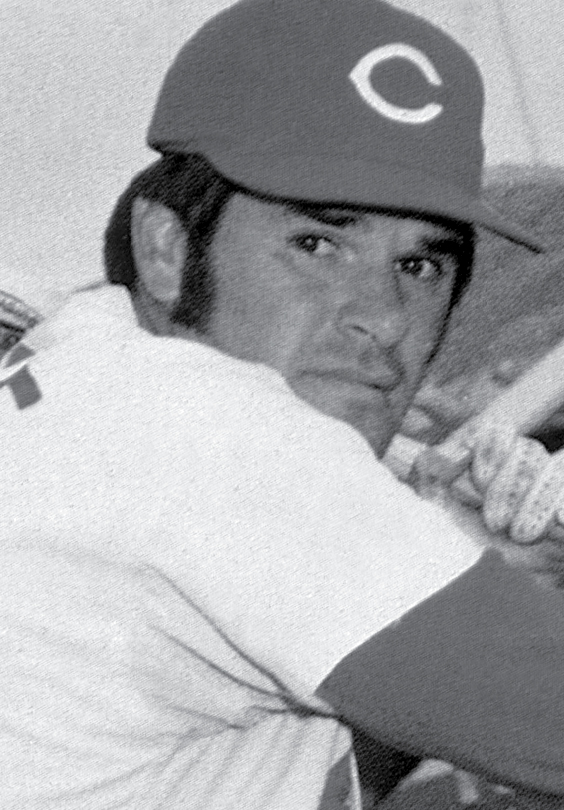

#20 Peter Edward “Charlie Hustle” Rose Sr.

OF-1B-2B-3B, Reds, Phillies, Expos, 1963–86

Versatile, tough and durable, the accomplishments of Pete Rose ensure him a place in the highest pantheon of baseball immortals. But his wrong-thinking attitude toward his gambling problem makes it difficult to envision him in the baseball Hall of Fame anytime soon.

Rose is the most prolific switch-hitter ever. He is the all-time leader in base hits with 4,256, singles with 3,215, at bats with 14,053 and games played with 3,562. He is second all-time in doubles with 746 and collected more than 200 hits in a season 10 times, which is a record. He made 100 or more hits 23 consecutive years, which is also a record.

Rose is the only player in baseball history to play more than 500 games at five positions: first base, second base, third base, right field and left field, and was named the Player of the Decade by the Sporting News for the 1970s. He won two Gold Gloves playing in right field for the Reds.

Fans loved Rose’s hustle, even those whose teams were beaten by him. He began running to first base after being issued a walk after he saw Enos Slaughter, another hustling guy, do it. Rose popularized the head-first slide, although baseball purists insist that the slide is not as effective as a feet-first attempt. Still, it was another example of a guy who was trying to squeeze every ounce of talent out of his body. Rose clearly did.

On September 11, 1985, batting left-handed for the Reds, Rose hit a single to left field off the Padres’ Eric Show to record his 4,193rd hit, passing Ty Cobb and breaking a record many thought unbreakable.

That said, he has admitted to gambling on baseball games. In 2004, he released a book that detailed some of those gambling exploits, and went on a national tour to publicly apologize. But sportswriters, stung by Rose’s previous adamant stance that he did not bet on the game, have so far been largely unforgiving. Baseball fans have been a little easier on Rose, and acknowledge his greatness. But it may be a long while before Rose is elected to the Hall of Fame, which is his last goal in baseball.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .303, HR: 160, RBI: 1,314, H: 4,256, SB: 198

#21 Rogers “Rajah” Hornsby

2B-SS-3B-1B-OF, Cardinals, Giants, Braves, Cubs, Browns, 1915–37. Hall of Fame, 1942

The greatest right-handed hitter in baseball history was also one of its biggest curmudgeons.

On the field, Hornsby was a joy to watch. Hornsby stood at the back of the batter’s box and executed a perfectly level swing that delivered the baseball to all corners of the field. In the early part of his career, Hornsby had some speed; he was quick out of the batter’s box, and would always take the extra base against an unwary outfielder.

Hornsby led the league in doubles four times, in triples twice, in home runs twice, and in RBI four times. His Triple Crown year in 1922 was one of the greatest seasons any player has ever had in baseball history: His .401 batting average, 42 homers, 152 RBI, 46 doubles, 250 hits, 141 runs scored, .459 on-base percentage and .722 slugging average were all league leaders. And his .967 fielding percentage was the best in either league for a second baseman. He also had a 33-game hitting streak that year.

His .424 batting average in 1924 was the highest average in baseball history after 1900 (four players before that year did post better averages). Only Ty Cobb’s lifetime batting average tops Hornsby’s .358.

But Hornsby could be, well, difficult. He was very confident of his ability and had no problem reminding teammates or his manager of it. Hornsby had a major issue when dealing with authority, and often quarreled with managers and front-office types. As good as he was, that was not a good idea, and he was traded four times in his career.

He also had a whopper of a gambling problem. It didn’t seem to affect him much in his early career, but it got worse as he got older. He managed the Cubs from 1925 to 1926, and was known to hit up his players for loans to cover his gambling losses. Again, not a good idea.

He ended his career with the St. Louis Browns, and, as he got older, he coached for several organizations, and seemed to mellow a bit. Still, Chicago Cub great Billy Williams will always remember his first tryout with the Cubs. The Rajah was overseeing it, and, when the tryout was over, Hornsby pointed to Williams and budding third baseman Ron Santo. Those two, Hornsby, said, will play in the big leagues. The rest of you, Hornsby said, might as well go home. And of course, Williams conceded, Hornsby was right. Except for Santo and him, none of the other players made it.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .358, HR: 301, RBI: 1,584, H: 2,930, SB: 135

#22 Oscar McKinley “Charlie,” “The Hoosier Comet” Charleston

CF-1B, Indianapolis ABCs, New York Lincoln Stars, Chicago American Giants, Harrisburg Giants, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Philadelphia Stars, Indianapolis Clowns (Negro Leagues), 1915–41. Hall of Fame, 1976

Charleston had a barrel chest and spindly legs, and played the outfield, which drew comparisons to white slugger Babe Ruth. But he was closer to Ty Cobb as a hitter and to Tris Speaker as a defensive player. What it all meant was that Charleston is believed by some to be the greatest all-around player in Negro League history.

Charleston was born in Indianapolis in 1896. After a stint in the Army, Charleston joined the Indianapolis ABCs as a pitcher-outfielder. Eventually, he was moved to the outfield permanently, and he soon became a star.

Charleston was an exceptional hitter with good power. Available records show him putting together back-to-back .400 seasons in 1924 and 1925, while playing for the Harrisburg Giants of the Eastern Colored League.

He was also an aggressive base runner. Several times, playing for several leagues over the years, Charleston would lead the circuit in stolen bases and home runs. Tales of Charleston’s baserunning never fail to emphasize that he was not afraid to slide into opponents with his spikes high, much like his white contemporary, Ty Cobb.

Defensively, Charleston’s exceptional speed enabled him, like Speaker, to play a very shallow center field. He, like Speaker, would often snag a line drive and run over to second base to double up the runner.

In 1931, Charleston was the best player on one of the best, if not the best, Negro League teams of all time, the Homestead Grays. Charleston played center field and hit .351. In a nine-game “world championship” series against another all-time great team, the Kansas City Monarchs, the Grays won the series, five games to four, and Charleston hit .511.

As he grew older and his legs began to bother him, Charleston moved from center field to first base. But he could still hit. Playing for another all-time great team, the 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords, Charleston hit .294 and led the team to another Negro League World Series win over the New York Cuban Stars.

Charleston was coveted by white big-league managers and owners, and no wonder: He holds the all-time record with 18 home runs in games between Negro League teams and white major league teams. But he came along a little too early to break into the major leagues.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .330, HR: 169

#23 Denton True “Cy” Young

RHP, Cleveland Spiders, Cardinals, Red Sox, Indians, Braves, 1890–1911. Hall of Fame, 1937

Cy Young not only set the world record for winning baseball games by the end of his amazing career, he truly sparked the evolution of baseball itself. When Young started, pitchers threw out of a box 50 feet from home plate. By the time he retired, pitchers stood on a mound 60 feet, six inches from the plate and fired the ball in.

Young was effective either way. He won 30 or more games five times in his career, and 10 other times won 20 or more. He led the league in wins five times, in shutouts seven times and in saves twice. He won more games (511), lost more (316), pitched more innings (7,354 2/3) and completed more games (749) than any pitcher, ever. He was durable, versatile and tough as nails.

His nickname was reportedly earned when he was being warmed up by a young catcher in his minor league days, and several of his pitches got past the young man and damaged a fence behind the fellow. The catcher remarked that the fence looked like a “cyclone” had hit it, and thus was born the tag.

Young became a canny veteran only two or three years into his professional career. He threw a fastball and curve, and he threw those pitches from various angles at various speeds. He also understood that many major league teams of the 19th century didn’t like to use up too many balls during a game, as the balls cost money. So those balls tended to get softer and more lopsided as games went on. Young rarely asked an umpire for a new ball, because he could make lopsided or scuffed balls dance like an ant on a hot stove.

But Young’s greatest secret was that he was as limber as an Indian yogi. He rarely warmed up by throwing more than a handful of pitches, and was usually ready to pitch again on a day’s rest. This advantage appeared to be a natural one, as Young clearly wasn’t an exercise buff, particularly at the end of his career. By 1911, Young had to retire, because at 44, he was so rotund that batters would bunt on him and make him field the ball.

No matter, Young was a great, great pitcher for many years, and he is now annually honored by the most valuable pitcher’s award that carries his name. No one deserves it more.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 511, L: 316, SV: 17, ERA: 2.63, SO: 2,803, CG: 749

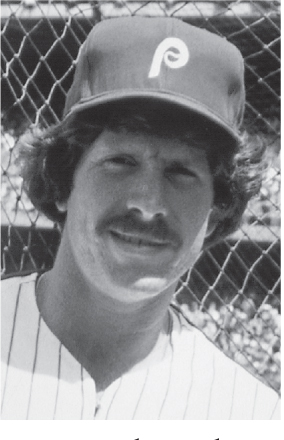

#24 Michael Jack Schmidt

3B, Phillies, 1972–89. Hall of Fame, 1995

Great hitting always overshadows great defense. That’s a fact, and that’s why it’s so important to emphasize that while Mike Schmidt might not be as acrobatic a third baseman as Brooks Robinson or Graig Nettles, he was probably a better overall fielder.

But let’s talk about hitting first, because first and foremost, Mike Schmidt was an offensive machine. He led the National League in home runs eight times, in RBI four times and in slugging percentage five times.

He had an early problem with strikeouts, whiffing a league-high 180 times in 1975. But Schmidt eventually became more selective at the plate, and four times in his career, led the league in walks.

On July 17, 1986, Schmidt hit four home runs in one game, as the Phillies rallied from a 13–2 deficit to defeat the Cubs 18–16 in 10 innings. He hit his first home run off Cub starter Rick Reuschel and his fourth off Cub reliever (and Rick’s brother) Paul Reuschel.

He was also a smart base runner. He stole 174 bases in his career, and twice swiped 20 or more. He won MVP awards in 1980, 1981 and 1986. He was also the MVP of the World Series in 1980, hitting .381 with two home runs and seven RBI in Philadelphia’s win over the Royals.

In the field, Schmidt was a 10-time Gold Glove winner. In 1974, he set a National League record for third basemen with 404 assists. Three years later, his 396 assists were the second-highest single season total in major league history.

He was also tough to keep out of the lineup. Until a season-ending rotator-cuff injury in 1988, Schmidt played in 145 or more games in 13 of his 16 full seasons in the league.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .267, HR: 548, RBI: 1,595, H: 2,234, SB: 174

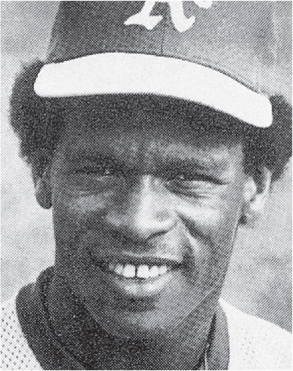

#25 Rickey Henley Henderson

OF-DH, A’s, Yankees, Blue Jays, Padres, Angels, Mets, Mariners, Red Sox, Dodgers, 1979–2003. Hall of Fame, 2009

Henderson was the greatest leadoff hitter in baseball history, and one of the best outfielders, ever, as well.

His numbers are prodigious. Henderson is the all-time leader in walks with 2,190, breaking Babe Ruth’s record on April, 25, 2001. (Henderson led the league in walks four times in his career, and was in the top five eight other times.)

Later that season, on September 28, 2001, Henderson broke Ty Cobbs’s all-time record for runs scored when he crossed home plate for the 2,247th time. Henderson now has 2,295 career runs scored. When you break records by Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb in the same year, you are good.

Henderson is also the all-time leader in stolen bases, a record he broke more than a decade ago, in 1992. Henderson ended his career with 1,406 stolen bases. Lou Brock, in second place, has 938.

Henderson is the only player to steal more than 100 bases more than twice, doing it three times in his career. In 1982, he stole 130 bases, setting the modern major league record. (Hugh Nicol of the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the defunct American Association stole 138 bases in 1887.)

Henderson stole 108 bases in 1983 and 100 bases in 1980. He led the league in stolen bases 12 times, including seven times in a row from 1980 to 1986.

He has hit 79 leadoff home runs, another record. That sum is more than the next two players combined, Brady Anderson (44) and Bobby Bonds (34).

Henderson is also one of the most adept players in major league history at getting hit by a pitch, doing so 98 times in his career, which places him 56th on the all-time roster.

His speed enabled him to be a very good defensive outfielder. Henderson won only one Gold Glove in his career, but he is sixth all-time in putouts in the outfield with 6,466.

Henderson may have lost a few points with purists with his “snap” catches in the outfield. This was a move where he whipped his glove across his head to grab a fly out.

Henderson was a clutch player in the postseason. He hit .339 in 14 World Series games.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .279, HR: 297, RBI: 1,115, H: 3,055, SB: 1,406

#26 Jack Roosevelt “Jackie” Robinson

2B-3B-1B-OF, Dodgers, 1947–56. Hall of Fame, 1962

Yes, yes, yes, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, became an icon and a hero to every African-American boy of the next generation and paved the way for baseball as we know it now.

But what sometimes gets lost in all this is that Robinson was a really, really good baseball player.

Robinson was, in fact, one of the greatest athletes in the history of sport, any sport. Jim Thorpe may have been slightly better, but not by much.

For example, Robinson averaged a hard-to-fathom 11 yards per carry as a running back in his junior year at UCLA. He was the leading scorer in the Pacific 10 in basketball for three years running. He won the 1940 NCAA long jump championship, and was slated to go to the Olympics, had they not been canceled that year. He also won both the singles and doubles titles in the Western Tennis Club championships.

He was recruited by Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey to spearhead the long-overdue integration of baseball in 1946 and began playing in major league ballparks in 1947. Robinson endured extraordinary abuse from fans and opponents, yet held his emotions in check. He retaliated with a superb rookie season and was named Rookie of the Year. The rest, as they say, is history—American history, not baseball history.

Robinson was a superior base runner, perhaps the best ever. He stole home 19 times in his career. In 1955, he became one of only 12 players in baseball history to steal home in a World Series game. In 1954, he became the first National League player in 26 years to steal his way around the base paths. He was probably the best player in history at finding a way to return to base safely after being caught in a rundown.

Robinson was a good hitter, winning a batting title in 1949 and topping .300 six times in his career. He didn’t strike out much and averaged about 75 walks a season.

Defensively, he led the National League three times in fielding average at second base, and was also a very good defensive third baseman and left fielder. Robinson wasn’t flashy; he didn’t make the diving stab. Rather, he played very intelligently, and was usually in the right place at the right time.

At his death in 1972, his former teammate Joe Page spoke for all the black players then in the league, and in fact all the black players to come in the history of baseball, when he said, “When I look at my house, I say, ‘Thank God for Jackie Robinson.’”

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .311, HR: 137, RBI: 734, H: 1,518, SB: 197

#27 James Emory “Jimmie,” “Double X,” “The Beast” Foxx

1B-3B-C, A’s, Red Sox, Cubs, Phillies, 1925–45. Hall of Fame, 1951

The prototypical slugger of the 1920s and 1930s, Jimmie Foxx was called “the right-handed Babe Ruth” when he toiled for the A’s.

Foxx didn’t actually get his career started until 1929, four years after he was signed by the A’s. That’s because Connie Mack’s A’s were so deep that Foxx, who started out as a catcher, was sitting behind future Hall of Famer Mickey Cochrane for several years. When Mack finally moved Foxx to first base, he displaced veteran Jimmy Dykes.

But it was worth it. In Foxx’s first full season as a starter, he led the American League in on-base percentage, and batted .354 with 33 home runs and 118 RBI. To top it off, the A’s displaced the mighty New York Yankees as American League champions, and won the 1929 World Series over the Cubs. Foxx hit .350 in that Fall Classic, and added a pair of home runs.

In 1932, Foxx smacked 58 home runs, two short of Ruth’s record. A’s fans like to point out that Foxx hit two home runs in games that were eventually rained out. Foxx won back-to-back MVP awards in 1932 and 1933. The latter season, he won the Triple Crown, with 48 home runs, 163 RBI and a .356 batting average.

In 1938, after he was traded to the Red Sox, Foxx had another sensational season, leading the league with a .349 batting average, 175 RBI, 119 walks, a .462 on-base percentage and a .704 slugging percentage. His 50 home runs were second in the league to Hank Greenberg’s 58. But Foxx won the MVP.

He was a big dude. At six feet and 195 pounds, Foxx had huge upper arms and a powerful chest. Foxx would cut back the sleeves on his uniform so pitchers could see those biceps. He also had a great throwing arm and in fact pitched in 10 games in the majors, including two starts with the Phillies in 1945. His career record is 1–0 with a 1.52 ERA.

Foxx was also a very good teammate. He was especially kind to rookies, and Red Sox great Ted Williams recalled fondly how Foxx encouraged him and helped him when he was starting out in Boston.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .325, HR: 534, RBI: 1,922, H: 2,646, SB: 87

#28 William Roger “The Rocket” Clemens

RHP, Red Sox, Blue Jays, Yankees, Astros, 1984–2007

Think about this: There are only seven other hurlers in baseball history who have won more than 350 games in their careers, as Clemens has. All of them, except Walter Johnson and Warren Spahn, began their careers in the 19th century, an era in which pitchers pitched two or three or four times a week. It was a completely different era with a completely different philosophy of pitching.

Now think about this: In 1986, playing with the Boston Red Sox, Clemens set a Major League record by striking out 20 batters in a game against Seattle. Pretty good, eh? But 10 years later, in 1996, he tied that record while playing for Toronto. Set an all-time record once, that makes a guy an all-time player. Set it again a decade later, well, what does that make him?

The question becomes, in the latter part of his career, how much of these stats are abetted by performance-enhancing drugs? That we don’t know. But the numbers are terrific, either way.

And the man was still pitching, 23 years after he broke in. And he was not just hanging on. He dominated the Minnesota Twins to win his 350th game in June 2007, and he would have a better record had he gotten more run support from his team, the Yankees.

So is Clemens the greatest pitcher in baseball history? Well, put it this way: He’s 28th on my list, but it’s my opinion that there is a thin line between Roger Clemens and Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Grover Alexander, and Satchel Paige, the four pitchers ahead of him on the list. Seventh Game, World Series, on the road, I would gladly take any one of these guys.

In terms of other records, Clemens has won six Cy Young awards, in 1986, 1987, 1991, 1997, 1998, 2001 and 2004. He was also the American League MVP in 1986, the year the Red Sox almost won the World Series.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 354, L: 184, SV: 0, ERA: 3.12, SO: 4,672, CG: 118

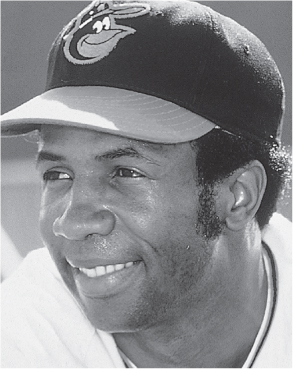

#29 Frank Robinson

OF-DH, Reds, Orioles, Dodgers, Angels, Indians, 1956–76. Hall of Fame, 1982

Frank Robinson was one of the great power hitters of the 1960s. He was also a leader in the clubhouse, which was a rarity for a black man in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Robinson made an immediate impact on the National League with the Cincinnati Reds in his first year, hitting 38 home runs, then a record for a rookie player. He also led the National League with 122 runs scored and was hit by pitches 20 times, another rookie record. For the next 10 seasons, Robinson was “the Man” in Cincinnati.

In 1961, Robinson led the Reds to the team’s first pennant in 21 years, although Cincinnati had the misfortune of playing the Roger Maris–Mickey Mantle Yankees in the World Series. Robinson won the first of two MVP awards that year, hitting .323, slugging a league-leading .611 with 37 home runs and 124 RBI.

Robinson’s aggressive play often led to nagging injuries, although he rarely sat down for any long stretch. Still, Reds officials believed he was losing his effectiveness in the mid-1960s. This led to a trade to the Baltimore Orioles in 1966 in one of the more lopsided deals in baseball history.

Robinson led the Orioles to the 1966 American League pennant, and a surprising upset of a powerful Los Angeles Dodger team in the World Series. Robinson that season won the Triple Crown and his second MVP award with a .316 batting average, 49 home runs and 122 RBI. He became the first player in baseball history to win MVP awards in both leagues.

He was the cornerstone of a late 1960s Orioles team that was dubbed “the best damn team in baseball” by Orioles manager Earl Weaver. They were, winning three consecutive American League pennants and beating the Cincinnati Reds in the 1971 World Series in five games, surely a sweet win for Robinson.

In 1975, Robinson became the player-manager of the Cleveland Indians, the first black man to be a big-league manager. In 1976, Robinson led the Indians to their first winning record (81–78) since 1968 and only their third winning record in 26 years. He would eventually manage the Indians, Giants and Orioles in an 11-year managing career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .294, HR: 586, RBI: 1,812, H: 2,943, SB: 204

#30 Edwin Lee “Eddie” Mathews

3B-1B-OF, Braves, Astros, Tigers, 1952–68. Hall of Fame, 1978

No less an authority than Ty Cobb once remarked that Eddie Mathews’s swing was the most perfect he had ever seen.

Mathews was the best third baseman of his era, a powerful, agile man with a cannon for an arm and tremendous pop in his bat. His 486 home runs as a third baseman (he has 512 overall) was a record until Mike Schmidt broke it.

Mathews was one of the best high school baseball players of any era, and he signed with the Boston Braves on the night of his high school graduation in 1949. He spent only a couple of years in the minors before being brought up to Boston in 1952.

Mathews played well in 1952, but in 1953, he blossomed. He had one of the best seasons a 21-year-old player ever had, hitting .302 with 135 RBI and a league-leading 47 home runs.

Mathews’s improvement coincided with the ascension of the Braves. After several moribund decades in Boston, the Braves moved out to the Midwest. They were embraced by the city of Milwaukee, and were strong pennant contenders throughout the 1950s, reaching the World Series in 1957 and 1958.

Mathews, along with Hank Aaron, Lew Burdette and other stars, was one of the keys of the team. After losing a heartbreaking pennant race to the Dodgers in 1956, the Braves came back in 1957 and won the world championship over the Yankees in a stirring seven-game Series.

Mathews was one of the stars of the Series. His 10th-inning home run off Bob Grim won Game Four, and his backhanded grab of a Bill Skowron line drive in Game Seven was the final out of the Series. He only hit .227 in the seven-game matchup, but four of his hits were for extra bases.

Mathews was still a fixture at third base for Milwaukee into the mid-1960s, but his power numbers declined after 1961. In 1966, the Braves moved from Milwaukee to Atlanta, making Mathews the only player to play in three cities with one franchise.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .271, HR: 512, RBI: 1,453, H: 2,315, SB: 68

#31 John Henry “Pop,” “El Cuchara” Lloyd

SS-2B-1B-C, Cuban X-Giants, Philadelphia Giants, Leland Giants, New York Lincoln Giants, Chicago American Giants, New York Lincoln Stars, Brooklyn Royal Giants, New York Bacharach Giants, Atlantic City Bacharachs, Columbus Buckeyes, Hilldale Daisies, Harlem Stars (Negro Leagues), 1906–32. Hall of Fame, 1977

Lloyd was the best Negro League shortstop ever, and one of the best players, black or white, in the first part of the 20th century. Honus Wagner, the great shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates and a contemporary of Lloyd’s, said it was an honor to be compared with him.

Lloyd began his career as a catcher with the Macon Acmes of Georgia, an impoverished semipro black team. In fact, the Acmes were so impoverished that they couldn’t provide Lloyd with a catcher’s mask. He had to run a rope through a wire basket and tie it around his head for protection. Needless to say, when Ed LeMarc, owner of the Cuban X-Giants, offered him a contract, Lloyd jumped at the chance. He also decided to become an infielder.

Lloyd was a lanky man, 5'11" and about 180 pounds. He had a powerful throwing arm and ran the bases with long, smooth strides. He seemed to glide along the base paths, and that gait had the advantage of making it seem as though Lloyd was slower than he really was.

Lloyd was a left-handed, line-drive hitter who batted in a closed stance. In the batter’s box, Lloyd cradled the bat almost in the crook of his left elbow. As the pitch came in, the bat would whip off his arm like a coiled snake and lash the ball to all fields.

He was as fundamentally sound a player as there was in those days. Lloyd had superior bat control, and could execute the hit-and-run on command, as well as drop a bunt down either base line.

Lloyd was a popular teammate who didn’t smoke, drink or curse. But while he was a gentleman on and off the field, he was a man who was well aware of his worth. He played for a number of teams in his career because he drove a hard bargain, and if he did not get it, he would look around for another employer. And up until the early 1930s, he was always able to find one.

One of his nicknames came from his years in the Cuban Leagues. His large hands would often scoop up dirt and pebbles when he grabbed for the ball, and teammates and opponents alike began calling him “el Cuchara,” or the Shovel.

His other nickname came from his later years as a manager. As intense a competitor as Lloyd was, he was an easygoing manager who was particularly patient with rookies. His players called him “Pop,” a term of endearment.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .337, H: 970

#32 Melvin Thomas “Master Melvin,” “Mel” Ott

OF-3B-2B, Giants, 1926–47. Hall of Fame, 1951

Mel Ott was a coach’s nightmare at the plate. He had a “foot in the bucket” batting stance, in which he raised his right leg just as he swung the bat, and then hooked upward as he completed his swing.

But Ott was a heck of a lot more effective than a lot of guys who had better-looking swings. He was the first National League player to hit 500 home runs, and held the record until fellow Giant Willie Mays broke it in 1967. Ott led the league in homers six times in his career.

He also had an excellent eye in the batter’s box, leading the league six times in walks, and holding that record, as well, until Joe Morgan broke it in 1982.

Ott was signed by the Giants as a 15-year-old and by the time he was 16, he was sitting on the Giants’ bench. New York coach John McGraw loved Ott’s athleticism, and initially wasn’t quite sure where to play the kid. So he had Ott working out at third base, second base and in the outfield. Eventually, the outfield was where Ott would see a majority of action throughout his career.

Ott was a wet-behind-the-ears 19-year-old when he became a regular in the Giants’ outfield. The New York papers joshingly called him “Master Melvin” in reference to his age and schoolboyish looks.

There was nothing boyish about the way Ott played, however. He hit .322, with 26 doubles and 18 home runs in his first full season. The next year, he socked 42 home runs and had 151 RBI, both career highs.

McGraw didn’t really like the leg kick, but he never tried to change Ott, because it was clear that the leg kick gave Ott that much more power. At 5'9", and between 170 and 180 pounds during his career, Master Melvin needed a little help.

Born in Louisiana, Ott was the classic Southerner. He was a gentleman in a game where gentlemen were the exception rather than the rule. In fact, Ott was the player to whom famed Dodger coach Leo Durocher referred when he uttered his famous quote, “Nice guys finish last.” It was untrue in Ott’s case: He played in three World Series, and hit .389 with two home runs as the Giants won the 1933 world championship.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .304, HR: 511, RBI: 1,860, H: 2,876, SB: 89

#33 Carl Michael “Yaz” Yastrzemski

OF-1B-DH, Red Sox, 1961–83. Hall of Fame, 1989

Yastrzemski did everything well, and he did it well for a long time. The 5'11" Yastrzemski was a baseball and basketball standout from Long Island who signed with Notre Dame to do both, but left the university when he signed a baseball contract after his freshman year.

Yaz was being groomed to be Ted Williams’s replacement in left field, a hefty load for anyone’s shoulders. And when Williams retired after the 1960 season, Yastrzemski moved right into his left-field slot. He didn’t overpower anyone in 1961, hitting .266 with 11 home runs, 80 RBI and 155 hits. But he did lead the team in total bases with 231 and extra base hits with 48.

Yastrzemski improved considerably in 1962, hitting .296 with 19 homers, 191 hits and 94 RBI. And in 1963, Yaz arrived, winning his first batting title with a .321 average and leading the league in hits with 183 and an on-base percentage of .418.

By the 1963 season, Yastrzemski was a fixture in left field. And the Red Sox, mired in mediocrity, were beginning to climb back toward respectability over the next few seasons.

In 1967, Yastrzemski put it all together, winning the Triple Crown with a .326 batting average, 44 home runs and 121 RBI, which also earned him an MVP award. Not coincidentally, the Red Sox also put it all together, winning their first American League championship since 1948. Boston lost a thrilling seven-game World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals, but Yastrzemski hit .400 with three home runs to lead the Sox. The 1967 season remains the most exciting season in Red Sox history, and one of the most exciting in baseball history.

With all his offensive numbers, it is easy to overlook the fact that Yastrzemski was also a great defensive player. He won seven Gold Gloves over his career, and led American League outfielders in assists in 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1966. He owned the Green Monster, which is the term Boston fans use for the left-field wall in Fenway Park. Yastrzemski knew every rivet, every dent and every nuance of the Wall, and his presence in left was a huge advantage for Boston.

In 1979, Yastrzemski became the first American League player to make 400 home runs and 3,000 hits. Three other players, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Stan Musial, did it in the National League.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, HR: 452, RBI: 1,844, H: 3,419, SB: 168

#34 Warren Edward Spahn

LHP, Braves, Mets, Giants, 1942–65. Hall of Fame, 1973

Spahn was the winningest left-handed pitcher of all time, and one of the greatest hurlers, left-handed or right-handed, in baseball history.

Because of his military service in World War II, Spahn didn’t really get a chance to show his stuff until 1946. He had a brief stint with the Braves in 1942, but didn’t come away with any decisions that year.

But when he returned from the war, “Spahnie,” as some of his teammates called him, began to display the kind of pitching that would make him a star in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s. He went only 8–5, but his 2.94 ERA led the team.

By 1947, Spahn went 21–10, the first of a major league record-tying 13 seasons with 20 or more wins. Eight times he would lead the National League in wins, including five years in a row, from 1957 to 1961. His 63 shutouts place him sixth all-time in the National League record books.

He was the mainstay of a Braves staff that, most years, wasn’t very deep. In the late 1940s, Boston fans rested their hopes on Spahn and fellow pitcher Johnny Sain most years. It was, as most Braves fans knew, “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain.”

Spahn began his career as a fastball pitcher who also could throw his curve for strikes. And from 1949 to 1952, he led the league in strikeouts. But as he got older, Spahn got smarter. He added a screwball and a slider, and he was the best of his generation in changing speeds on all those pitches.

In 1960, at the age of 39, Spahn pitched his first no-hitter. The next season, five days past his 40th birthday, he pitched his second.

The Braves won the National League crown in 1957 and again in 1958, and Spahn was at the top of his game. He won the Cy Young award in 1957, with a league-leading 21 wins, as well as 111 strikeouts and a 2.69 ERA. In 1958, he might have been even better, with 22 wins, a .667 winning percentage, 23 complete games and 290 innings pitched, all tops in the National League.

Spahn began to slow down in the early 1960s, and the Braves sold him to the Mets in 1965. He spent part of his season in New York and later was shipped to the Giants. He was released after the season, but continued to pitch in the minors for two more years before retiring at age 46.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 363, L: 245, SV: 29, ERA: 3.09, SO: 2,583, CG: 382

#35 Napoleon “Larry” Lajoie

2B-1B-SS-3B, Phillies, A’s, Indians, A’s, 1896–1916. Hall of Fame, 1937

Lajoie was the greatest second baseman of the so-called “dead ball” era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The muscular 6'1", 195-pound Lajoie would not be considered a “power hitter” in this era, as he rarely cracked double figures in home runs during his career. But he was a very strong right-handed pull hitter who regularly cowed third basemen with his searing line shots down the left field line. He led the league in doubles five times, and hit 40 or more two-baggers seven times in his career. He also stroked 10 or more triples in a season six times.

He was a graceful and fundamentally sound second baseman, six times leading his league in fielding percentage at that position.

Lajoie began his career with the Philadelphia Phillies, but when Ban Johnson started up the American League in 1901, Lajoie jumped across town to the A’s. Lajoie, along with several other ex–National League stars, gave the new league instant credibility. In that first year with the A’s, Lajoie won the Triple Crown, with 14 home runs, 125 RBI and a .426 batting average. The latter figure remains the American League record.

Lajoie’s A’s easily outdrew the Phillies that year, so the National Leaguers obtained an injunction preventing him from playing in Philadelphia during the 1902 season.

Not to be outdone, Johnson ordered Lajoie’s contract transferred to Cleveland. Lajoie quickly became a star with his new club, as well, winning back-to-back batting titles in 1903 and 1904.

In 1910, Lajoie and Detroit star Ty Cobb were locked in a race for that year’s batting crown. The league would award a Chalmers automobile to the best hitter. On the last day of the season, Lajoie bunted for seven infield hits and slapped a triple in a doubleheader at St. Louis. He still fell short by a point to Cobb, with his .384 average.

But later, St. Louis manager Jack O’Connor revealed he had ordered his third baseman to play deep against Lajoie, thus enabling Lajoie to bunt down the third-base line successfully. O’Connor was fired. The league gave both Cobb and Lajoie automobiles.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .338, HR: 83, RBI: 1,599, H: 3,242, SB: 380