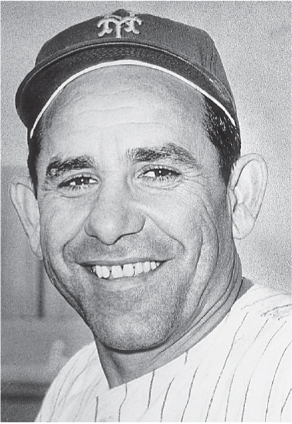

#36 Lawrence Peter “Yogi” Berra

C-OF, Yankees, 1946–65. Hall of Fame, 1972

Maybe it’s because he doesn’t look like a great athlete. Maybe it’s because of all those odd sayings he is credited with uttering. But there are still baseball fans who are reluctant to regard Berra as the greatest catcher in baseball history. He is.

The hitting speaks for itself. Berra hit 10 or more home runs 16 years in a row, and 20 or more home runs 11 times, including 10 years in a row. He hit over .300 four times. He had over 90 RBI nine times. He hit 20 or more doubles eight times. In short, Berra’s offensive prowess gave the Yankees a huge advantage over just about every other team in baseball in the 1950s.

Between 1949 and 1955, Berra led the Yankees in RBI every season and won MVP awards in 1951, 1954 and 1955.

He was, by far, the best bad-ball hitter ever in the American League. Berra’s hand-eye coordination enabled him to golf low pitches right out of the ballpark, or slash at eyebrow-high offerings for base hits. And, according to most of the ballplayers who played with and against him, Berra was the toughest out in the last three innings in baseball for most of his career.

Yet for all that aggression at the plate, Berra was very tough to strike out. He never whiffed more than 38 times in a season, and averaged only 22 strikeouts per year.

But he was also an excellent fielder. He became one of four catchers to record a 1.000 fielding average in a season when he did it in 1958. He led the league in games caught and chances accepted by a catcher eight times, and led the league in double plays six times

Finally, Berra was an excellent handler of pitchers. That is said of most great catchers, but that’s the point. Yogi was a great catcher. He caught Allie Reynolds’s two no-hitters in 1949 and, of course, also caught Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, HR: 358, RBI: 1,430, H: 2,150, SB: 30

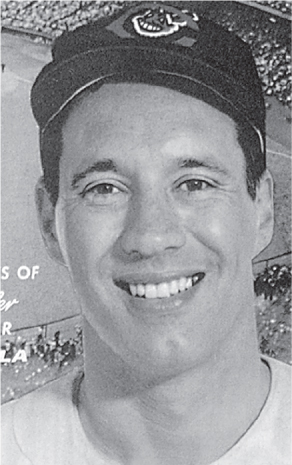

#37 George Thomas “Tom Terrific” Seaver

RHP, Mets, Reds, White Sox, Red Sox, 1967–86. Hall of Fame, 1991

Seaver is fondly recalled by Mets fans as the first true star the franchise ever had.

Seaver was a star at the University of Southern California when he signed a contract with the Braves for $40,000. The contract was voided on a technicality, so the NCAA and baseball commissioner William Eckert offered Seaver’s services to any team who would match the Braves’ offer. The Phillies, Indians and Mets did so, and the names of all three teams were placed in a hat in the commissioner’s office. The Mets won when Eckert pulled their name out of the hat.

The whole thing obviously paid off handsomely. A year after the drawing, Seaver went 16–13 for a truly horrible Mets team that finished last, 401/2 games behind St. Louis. Not surprisingly, Seaver made the All Star team.

Seaver went 16–12 for another bad Mets team the next season and had his breakout year in 1969, going 25–7 and winning the Cy Young award. The Mets, of course, won the World Series over the Orioles.

Baseball historian Bill James suggests that, given Seaver’s amazingly consistent performance with teams that, for the most part, didn’t score a lot of runs for him, he may have been the greatest pitcher of all time. It’s not an unreasonable point. Seaver was good when his teams were bad, and when he had a little help in terms of better run production and more consistent relief, he was very, very good. He won three Cy Young awards, in 1969, 1973 and 1975, won 20 or more games five times and led the league in wins three times.

He was the consummate professional, a fanatic about conditioning and a perfectionist on the field. He fired three one-hitters and one no-hitter. That came on June 16, 1978, shutting down the Cardinals. Seaver won his 300th game with the White Sox in 1984, firing a complete game, six-hitter to beat the Yankees, 4–1.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 311, L: 205, SV: 1, ERA: 2.86, SO: 3,640, CG: 231

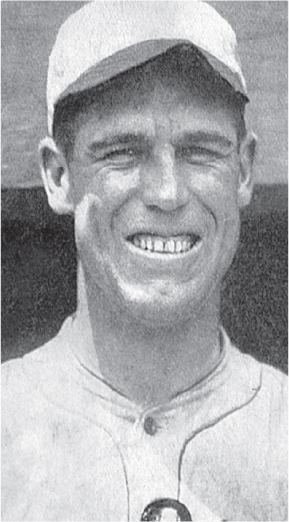

#38 Robert William Andrew “Rapid Robert” Feller

RHP, Indians, 1936–56. Hall of Fame, 1962

Interestingly, although Bob Feller was clearly the fastest pitcher of his era, he always credited his numerous strikeout records to his curveball and slider.

Feller was something of a prodigy when he got to the big leagues. He was signed by Cleveland as a 17-year-old and brought up to the big club immediately. In his major league debut against the St. Louis Browns near the end of the 1936 season, he struck out 15 batters. Later in the year, Feller struck out 17 men in a game against the A’s.

Curveball and slider notwithstanding, it was Feller’s fastball that was doing all the damage initially. Feller threw an extremely “live” ball, which meant that it jumped around as it neared the plate.

And with this velocity came a certain degree of wildness, at first. In 1937, Feller’s first full year with Cleveland, he struck out 150 and walked 106. In 1938, the year he led the league in strikeouts with 240, he also walked 208, which was a major league record at the time.

But Feller was already learning to nick the edge of the plate with his fastball. The 1938 season was the first of seven years he would lead the league in strikeouts. He won 20 or more games six times, and also led the league in complete games six times.

Feller fired three no-hitters, including an opening-day gem against the White Sox in 1940. Feller also threw 12 one-hitters.

Feller lost four years to World War II, but when he returned to baseball in 1946, he had clearly lost nothing off his fastball. His 348 strikeouts broke Rube Waddell’s league record, and in 1948, he led the Indians to their first World Series championship in 28 years.

But after that season, the Feller fastball lost a little speed, and Rapid Robert became a little more canny on the mound. He had one more solid season in 1951, leading the league in wins with 22. But in his final five years with the Indians, Feller was 36–31. He was a very effective spot starter with the Indians in 1954, when Cleveland once again won the pennant, but didn’t pitch in the World Series against the Giants.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 266, L: 162, SV: 21, ERA: 3.25, SO: 2,581, CG: 279

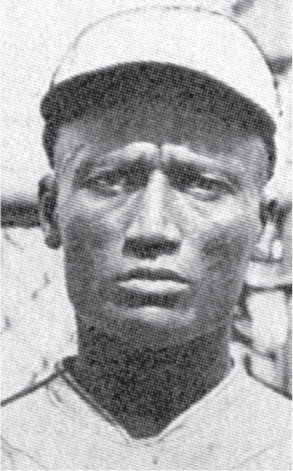

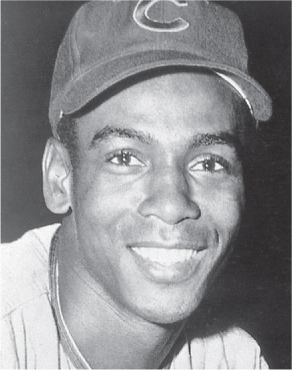

#39 Roy “Campy” Campenella

C-3B-OF, Baltimore Elite Giants (Negro Leagues), Brooklyn Dodgers, 1937–57. Hall of Fame, 1969

Campenella would rate much higher had his career not been shortened by an auto accident in 1958 that paralyzed him. Does he move ahead of Berra? Possibly. But that’s all speculation.

Campenella’s 20-year pro career began when he signed a contract to play with the Baltimore Elite Giants at age 15. He learned from one of the all-time greats: catcher Biz Mackey. He played behind Mackey for several years, but by 1941, Campenella was an all star, hitting .344 and inviting comparisons to Josh Gibson.

Campenella was a star in the Negro Leagues, and major league owners salivated at the chance of getting him. He eventually signed with the Dodgers, and was an All Star eight years in a row, from 1949 to 1956.

He was a great player, strong, yet surprisingly agile. He hit .300 or better three times, 20 or more home runs seven times, and won three MVP awards, in 1951, 1953 and 1955. From 1949 to 1956, the Dodgers won five National League pennants and defeated the New York Yankees in a memorable seven-game World Series in 1955. In that Series, Campenella hit .259 with three doubles and two home runs.

Campenella was a durable player, but like most catchers, he endured nagging injuries throughout his career, which, at times, affected his production at the plate. But he rarely begged off in a game, catching more than 100 contests for the Dodgers every season but his first.

Campenella’s 242 lifetime home runs were a record for a catcher at the time of his retirement in 1957, and he would have surely added to that total had he not been injured. But although he was in a wheelchair the rest of his life, Campanella spent most of the rest of his life working in community relations for the Dodgers until his death in 1993.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: 276, HR: 242, RBI: 865, H: 1,161, SB: 25

#40 George Harold “Gorgeous George” Sisler

1B-OF-P, Browns, Senators, Braves, 1915–30. Hall of Fame, 1939

The beginnings of Sisler’s career had an odd parallel with that of Babe Ruth’s. He began his professional career as a pitcher, and when he was eventually brought up to play for the St. Louis Browns, he was 4–4 in 1915 and 1–2 in 1916. He also played first base and in the outfield.

In 1916, in part-time duty, Sisler hit .305. It was time to make a decision, and Browns manager Fielder Jones didn’t have to think about it much. First base had been a problem for St. Louis for several years, so Sisler found a home there pretty quickly.

His hitting improved dramatically when he became a regular. In 1920, he hit .407 with 257 hits; the latter figure is a mark that still stands today. That year, he also smacked 49 doubles, 18 triples and 19 home runs. He hit safely in 131 of 154 games and closed out the season hitting .442 in August and .448 in September.

In 1922, he led the league with 246 hits and a .420 batting average, as well as a league-leading 51 stolen bases. In all, Sisler stole 30 or more bases six times in his career.

Sisler’s fielding ability is sometimes overshadowed by his hitting, but Sisler led the American League in assists seven times, and remains third on the all-time career leader list in assists by a first baseman with 1,529.

His career took a downswing in 1923, when he suffered from severe sinus problems, which in turn affected his eyesight. Sisler sat out the entire 1923 season. When he returned, his batting eye was not as acute as it had been previously, although he hit .300 six more seasons after his affliction. In 1929, at age 36, Sisler still managed to hit .326 with 205 hits.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .340, HR: 102, RBI: 1,175, H: 2,812, SB: 375

#41 Christopher “Christy,” “Big Six,” “Matty” Mathewson

RHP, Giants, Reds, 1900–16. Hall of Fame, 1936

Mathewson was probably not the clean-cut golden boy that newsmen of the day made him seem, but he was probably pretty close. And his pitching abilities were certainly not exaggerated.

“Big Six” (named after a famous fire engine in New York City) was a masterful control pitcher who possessed pinpoint accuracy and could vary the speed of his fastball, curveball and change-up so well that he appeared to have six or seven different pitches to call on.

Mathewson also was one of the early masters of what was then called the “fadeaway” pitch, which modern players call a screwball, because it broke in on right-handed hitters. The whole package was impressive.

Mathewson started his career slowly, going 34–37 from 1900 to 1902. But the 1902 season record was misleading: although he was 14–17 that year, Mathewson led the league in shutouts with eight. In 1903, he turned the corner, going 30–13, and never won fewer than 22 games for the next 12 years.

From 1903 to 1905, Matty was awe-inspiring. He won 30, 33 and 31 games, with a total of 18 shutouts and 685 strikeouts. He averaged about two walks per nine innings in that span, and in fact was always a very, very good control pitcher.

Eleven times in his career, Mathewson pitched 300 innings or more in a season. In the 1908 season, when he won a career-high 37 games, he led the league with a minuscule 1.43 ERA to go along with 259 strikeouts and threw 390 2/3 innings. He started 44 games and completed 34, while also saving five games.

He was John McGraw’s unofficial adopted son, and the McGraws and Mathewsons often spent time together in the off-season. In 1936, he was one of the five original players elected to the Hall of Fame.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 373, L: 188, SV: 28, ERA: 2.13, SO: 2,502, CG: 434

#42 Norman Thomas “Turkey” Stearnes

OF-1B, Detroit Stars, New York Lincoln Giants, Kansas City Monarchs, Cole’s American Giants, Philadelphia Stars, Chicago American Giants (Negro Leagues), 1923–42. Hall of Fame, 2000

At six feet, 175 pounds, the left-handed Stearnes had slim hips and a powerful upper body that enabled him to punch round-trippers out of Mack Park in Detroit for the Negro League Detroit Stars for several seasons.

In his first four seasons in the league, Stearnes belted 17, 10, 18 and 20 home runs for Detroit in a 70-game season, leading the league three times. In 1923, his rookie year, Stearnes made an auspicious debut against white big leaguers, as the Stars bested the St. Louis Browns of the American League, two games to one in an exhibition series. Stearnes hit .462 with two home runs in the three tilts.

In 1928, Stearnes led the Negro National League in home runs with 24, was second in triples with seven, third in doubles with 18 and hit .324 to win the unofficial MVP award.

In 1931, the Stars had trouble making their payroll, and Stearnes jumped to the Chicago American Giants. The team won two pennants in two years. In a playoff series in 1941 against the Nashville Elite Giants, Stearnes hit .700 in five games as Chicago won easily.

In 1940, Stearnes jumped to the Kansas City Monarchs, and, along with stars Buck O’Neil, Newt Allen and Satchel Paige, won back-to-back championships in the Negro American League.

A free-swinger, Stearnes reportedly never learned to bunt until Chicago manager Dave Malarcher taught him. Malarcher also batted Stearnes in the leadoff spot, making him one of the few home run kings to hit in that position. In all, Stearnes won seven home run titles in the Negro Leagues.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .332, HR: 197, H: 1,308

#43 George Howard Brett

3B-DH, Royals, 1973–93. Hall of Fame, 1999

Hard work and a laser-like focus were the principal reasons George Brett became one of the greatest third basemen of all time.

Brett did not set the world on fire his first couple of years with the Royals. In his first full season, he hit two home runs and managed only 47 RBI. But Brett listened to his pitching coach, Charlie Lau, who taught him to wait on pitches and hit to all fields. In his second full season, 1975, Brett batted .308 and led the league with 13 triples and 195 hits.

In 1976, Brett led the league with 215 hits and 14 triples and earned his first batting championship with a .333 average. He became, over the next decade and a half, one of the most consistent players in the game.

From 1975 to 1990, Brett hit over .300 11 times. Three other times, he hit .290 or better. He had more than 100 RBI four times in that span and scored more than 100 runs four times as well.

In 1979, Brett became the sixth player in major league history to hit 20 or more doubles, triples and home runs in the same year. He also hit .329 and led the league in hits with 212.

But his best year was 1980, when he won the MVP award. Brett flirted with .400 through most of the season, and ended up hitting .390. He also had a 37-game hitting streak and led the league with a .664 on-base percentage. Ironically, it was a year in which Brett battled various nagging injuries all season, and ended up playing in only 117 games.

Brett was not a one-dimensional guy, though. He won a Gold Glove in 1985 for his play at third base, and was one of the more fundamentally sound defensive players of his era.

In 1987, after 14 years at third base, Brett was switched to first base to make way for rookie Kevin Seitzer. He made the transition work, hitting .290 with 22 homers that season. In 1990, at age 37, Brett won his final batting title, hitting .329 with a league-leading 45 doubles.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .305, HR: 317, RBI: 1,595, H: 3,154, SB: 201

#44 Johnny Lee Bench

C-3B, Reds, 1967–83. Hall of Fame, 1989

The greatest catcher in National League history, Bench was a certified star almost as soon as he donned a catcher’s mask for the Cincinnati Reds in 1967. At 18, after being named the MVP of the Carolina League, his uniform number was retired. A year later, he was playing in the major leagues, and by 1968, Bench was an All Star, hitting .275, with 15 home runs and 82 RBI. He set a rookie record by catching in 154 games, as well as hitting 40 doubles.

Bench was clearly a star, and he dominated the catcher’s position for the next 15 years. He batted either fourth or fifth for the Cincinnati “Big Red Machine” of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

He was a fearful weapon for the Reds, hitting 20 or more home runs 11 times in his career, driving in 100 or more runs six times and hitting 30 or more doubles five times. He had very good power for a catcher, hitting 45 home runs in 1970, a record for a catcher, and driving in 148 runs that same year, which was also a record for that position.

Bench was an MVP in 1970 and again in 1972, but those seasons were only marginally better than most of his career: He was always a very good player, consistent and productive.

That kind of production alone would have made Bench a star. But he was also, by far, the best defensive catcher in the National League for a large part of his career. He won 10 consecutive Gold Glove awards, from 1968 to 1977, and set a National League record by catching in at least 100 games in his first 13 full seasons. He had a tremendous throwing arm, among the best of all time.

Bench played in four World Series, hitting .279 with five home runs and 14 RBI. He also hit .370 in 12 All Star games.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .267, HR: 389, RBI: 1,376, H: 2,048, SB: 68

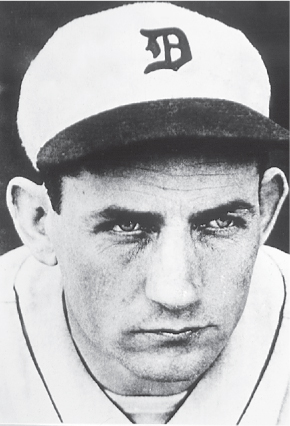

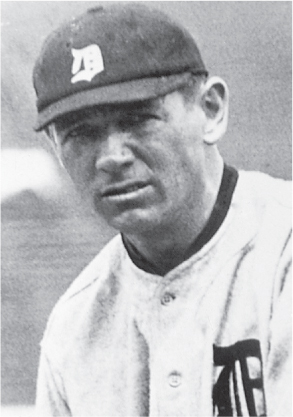

#45 Charles Leonard “The Mechanical Man” Gehringer

2B-1B-3B, Detroit, 1924–42. Hall of Fame, 1949

Gehringer was legendary for two things: His incredible consistency and his stoic demeanor. The latter contributed to a story that when he was being scouted by, among many clubs, the Tigers, Detroit player-manager Ty Cobb didn’t think much of Gehringer because of his lack of fire. Not true. Cobb later said, in what was also a bit of hyperbole, that after he saw Gehringer play at a tryout, Cobb was so eager to sign him that Cobb rushed off the field to the Tiger’s front office to meet with Gehringer without taking off his uniform.

Cobb probably took his time changing, but he knew what he had seen: a smooth-hitting, smooth-fielding second baseman who would be among the league’s elite a few years after he came up to the majors.

That was all correct. Gehringer signed with the Tigers out of the University of Michigan in 1924. By 1926, he was a regular, and by 1927, he was a star. The Senators’ Bucky Harris was slightly better afield, and the Yankees’ Tony Lazzeri was tougher out at the plate, but overall, Gehringer was the top man at second base.

He stayed there for more than a decade. Over the next 14 years, he topped .300 a total of 13 times. He hit 24 or more doubles 14 seasons in a row. He scored 100 or more runs 12 times and collected 200 or more hits seven times. In 1937, he won the batting title with a .371 average; had 96 RBI, 40 doubles and 14 home runs; and was MVP.

His nickname, “the Mechanical Man,” was bestowed upon Gehringer as a sign of respect for his abilities.

In the field, he was equally consistent. From 1929 to 1941, Gehringer led the league’s second basemen in fielding average seven times and was second three other times. He led the league’s second basemen in assists seven times and in putouts three times. He was so smooth at the position that he very rarely made spectacular plays: He was always in position, and the ball always seemed to come right toward him.

Gehringer was equally tough in the postseason, hitting .321 in three World Series, including a .375 average for the world championship team of 1935.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .320, HR: 184, RBI: 1,427, H: 2,839, SB: 181

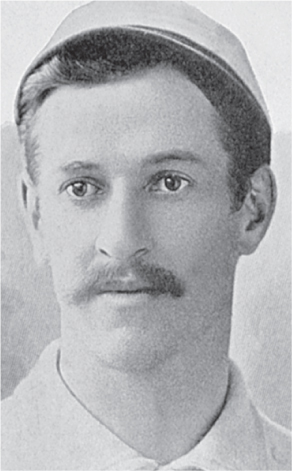

#46 Charles Augustus “Kid” Nichols

RHP, Braves, Cardinals, Phillies, 1890–1906. Hall of Fame, 1949

Nichols was the best pitcher of the 19th century, and the cornerstone of the Boston Braves dynasty of the 1890s, leading that team to five National League championships.

Nichols was a rarity among pitchers, then or now: He had a blistering fastball and pinpoint control even as a rookie. He went 27–19 as a rookie for the Braves, and led the league with seven shutouts. He completed all 47 games he started that year, and also appeared in relief in another contest.

Nichols was not a big man at 5'10", 175 pounds, but he threw very hard. He had a live fastball, a good curve and a decent changeup. He was, like the best pitchers of his day, extremely durable. Nichols pitched 400 or more innings a season five times and 300 or more innings a year seven other times.

In addition, he was not afraid to pitch in relief on the days he didn’t start. Nichols led the league in saves four times in his career, although the league leader rarely had more than three or four saves in those days.

Most impressively, Nichols won 30 or more games seven times in his career, including four years in a row, 1891–94. In fact, although Cy Young was playing in the same league for the Cleveland Spiders, Nichols won more games in the 1890s and had a lower ERA. Young, who was actually two years older than Nichols, clearly was a dominant pitcher well into the 20th century. But in the 19th, the Kid was better.

Nichols never pitched a no-hitter, but came close several times. He had 48 shutouts. He started 561 games and completed 531, still fourth all-time. He remains the youngest player, at 30 years and nine months, ever to win his 300th game.

From 1891 to 1893, the Boston Braves won three consecutive National League championships. Nichols was 99-47 in that span, with 137 complete games, 11 shutouts and four saves.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 361, L: 208, SV: 17, ERA: 2.95, SO: 1,868, CG: 531

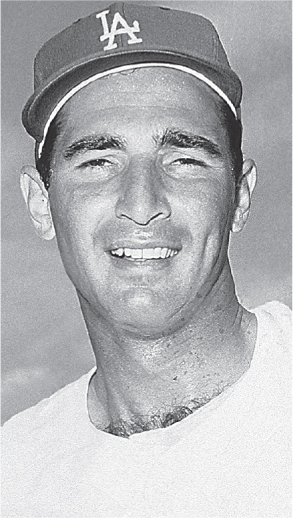

#47 Sanford “Sandy” Koufax

LHP, Dodgers, 1955–66. Hall of Fame, 1972

Koufax may not have possessed, technically speaking, the fastest fastball in major league history. But as countless former opponents would swear, it was the liveliest—a ball that rivaled the legendary heater of Jack Armstrong, the comic-strip all-American. A ball, which, like Armstrong’s, dropped down and then rose up on a batter in the same path to the plate, like a ping-pong ball in a wind tunnel.

Koufax was a slow starter as a big leaguer. He was a rookie on the 1955 Brooklyn World Series champs, cobbling together a 2–2 mark with a 3.02 ERA. But in his first major league start on August 27 against the Reds, he struck out 14 in a 7–0 win. Clearly, he had something.

But there were also afternoons when Koufax didn’t have it. In his first two years with the Dodgers, he was 4–6, striking out 60 and walking 57.

He became a regular in 1958, after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. In the more spacious confines of Dodger Stadium, Koufax felt he had a little more room for error. He was 11–11, with 131 strikeouts. Hitters batted a league low .223 against him.

As he cut down on his walks, Koufax got better and better. He added a sweeping curveball to go with the fastball. In 1961, he was 18–13 and led the league in strikeouts with 269. Koufax would lead the National League in strikeouts four times, including an amazing year in which he struck out 382 men, a league record, in only 335 innings.

In 1962, he pitched his first no-hitter. He would follow it up with a no-hitter every year until 1965. That final no-hitter was also a perfect game against the Cubs on September 7. He led the league in ERA five consecutive years, from 1962 to 1966. He won Cy Young awards in 1963, 1965 and 1966. Not coincidentally, those were also years in which the Dodgers won the National League crown.

In 1965, he won Game Five of the World Series against the Minnesota Twins on a four-hit shutout. He then came back three days later to win the Series by throwing a three-hit shutout.

Koufax retired after the 1966 season, nursing various arm troubles. But five years later, he became the youngest man ever to be elected to the Hall of Fame, at age 36.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 165, L: 87, SV: 9, ERA: 2.76, SO: 2,396, CG: 137

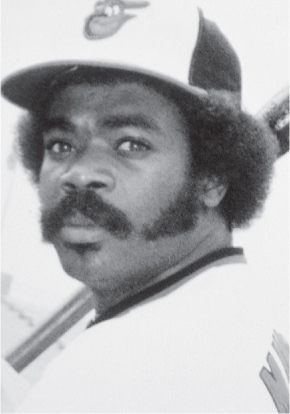

#48 Eddie Clarence Murray

1B-DH-3B, Orioles, Dodgers, Mets, Indians, Angels, 1977–97. Hall of Fame, 2003

Murray was a player who almost never had a bad year. And this was a guy who played for 21 seasons.

Murray had 110 or more hits and 20 or more doubles for 19 consecutive seasons. He hit 20 or more home runs in 16 seasons and had 90 or more RBI in 12 seasons. His 5,397 total bases are fifth all-time.

Murray never won a batting title, but hit over .300 seven times. In fact, Murray was such an overpowering hitter that he won the 1977 Rookie of the Year award as a designated hitter, the first player ever to accomplish that. He became a regular at first base the next season.

Murray won three Gold Gloves with the Orioles at first base, from 1982 to 1984. In 1981 and 1982, he led the league’s first basemen in fielding percentage, a feat he accomplished again in 1989, his first year with the Dodgers.

Murray’s low-key demeanor never seemed to bother a vast majority of his teammates, but fans and the Orioles ownership, specifically former owner Edward Bennett Williams, had a problem with it.

Ignoring Murray’s amazing consistency, Williams was often critical of his first baseman’s apparent lack of desire. Murray rarely endeared himself to the media, refusing to talk to the press for many years. The situation eventually became untenable, and Murray was eventually shipped to the Dodgers.

But after a slow start in 1989, Murray rebounded to hit a career-high .330 with Los Angeles. He was traded back to the East Coast in 1992 and responded by hitting .285, with 27 homers and 100 RBI for the Mets in 1993.

In 1996, after a stint in Cleveland, Murray returned briefly to the Orioles for the second half of the season, and helped his old team to the American League playoffs. He hit .400 in the first round of the playoffs against the Indians.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .287, HR: 504, RBI: 1,917, H: 3,255, SB: 110

#49 Harry Edwin “Slug” Heilmann

OF-1B-2B, Tigers, Reds, 1914–32. Hall of Fame, 1952

But for a grand total of 17 more hits, Heilmann would have hit better than .400 in four separate seasons. As it was, he hit .403 in 1923, .394 in 1921, .393 in 1925 and .398 in 1927, all league bests.

But, 11 more hits in 1921, five more hits in 1925 and one more hit in 1927, and Heilmann would have topped the .400 mark those other three times, as well. As it was, he hit .300 or better 11 other times in addition to his .403 in 1923.

Heilmann was a big man, 6'1", 200 pounds, with a choppy swing, who rarely saw a pitch he didn’t like. He wasn’t particularly patient at the plate, averaging about 65 walks per season. But he was equally difficult to strike out, whiffing 50 or fewer times 16 of the 17 years he played in the majors.

In short, Heilmann inevitably made contact. It was rarely pretty, but very effective.

Heilmann was one of those players who floated just under the radar screen. Yet he was a star in the league for most of his tenure. In addition to his four batting titles, Heilmann was in the top 10 league hitters six other times. He was in the top 10 in slugging percentage and in RBI 12 times in his career, in the top 10 in home runs in 11 seasons, in batting average and doubles in 10 seasons, in on-base percentage and hits in seven seasons and in triples six seasons.

Defensively, he is remembered as a mediocre fielder. But that’s based largely on a disastrous two-year switch to first base for the Tigers in 1919 and 1920, when he led the league in errors both years. When he returned to the outfield, Heilmann was a very good fielder. He led the league’s right fielders in assists in 1923, was second in 1926 and 1930, and third in 1928. He also led right fielders in putouts in 1925.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .342, HR: 183, RBI: 1,539, H: 2,660, SB: 113

#50 Ernest “Mr. Cub” Banks

1B-SS, Chicago, 1953–71. Hall of Fame, 1977

The greatest player in Cubs’ history, Ernie Banks was a consistent breath of fresh air for a franchise that didn’t have a lot of good years in the 1950s or 1960s.

Banks was a terrific athlete who, initially, wasn’t particularly interested in baseball. He was a football, track and basketball star in high school, and he enjoyed playing softball more than baseball as a youngster.

But in the early 1950s, baseball was where the money was. Banks played briefly in the Negro Leagues, which included a stint with the Kansas City Monarchs. But Jackie Robinson had broken the color line a few years prior, and the good black players were beginning to be snapped up by big league teams.

It wasn’t long before the Cubs discovered Banks. He was signed by Chicago in 1953 and brought up to the majors immediately. He played 10 games at the end of the season and hit .314. The next season, he was a regular and by 1955, Banks was a star.

His sunny demeanor and perpetual enthusiasm were legendary. When he would say, “It’s a great day for baseball. Let’s play two!” it was not an act. Banks had a fine appreciation for the game and where he would be if he were not playing it.

And he was a heck of a player. He started his career as the Cubs’ shortstop, and won MVP awards in 1958 and 1959. He led the league in home runs in 1958 (47) and 1960 (41). In fact, from 1955 to 1960, nobody in the majors, including Mickey Mantle and Henry Aaron, hit more home runs.

Defensively, he led National League shortstops in fielding percentage three times, and won a Gold Glove in 1960. He was switched to first base in 1962, but handled that change pretty well, leading the league in fielding percentage at that position in 1969 and leading first basemen in assists five times.

Banks retired in 1971, and the next year he became the first Cub to have his number retired.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .274, HR: 512, RBI: 1,636, H: 2,583, SB: 50

#51 Joseph Floyd “Arky” Vaughn

SS-3B, Pirates, Dodgers, 1932–43, 1947–48. Hall of Fame, 1985

Vaughn won the batting championship in 1935 while with Pittsburgh, hitting .385. He also led the league in walks for three years in a row, from 1934–36. He was one of the more accomplished shortstops, offensively, in baseball history.

Vaughn wasn’t considered a speedster, but, playing half his games in huge Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, he hit 10 or more triples eight times in his career, leading the league three times. He also hit 15 or more doubles 12 times in his career.

Vaughn’s nickname came from his state of birth, Arkansas, and he was generally considered a gentleman both on and off the field. But after he was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers, he had a dispute with manager Leo Durocher that kept him away from the game for three years. He returned in 1947 and was a bit player for two years before retiring for good.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .318, HR: 96, RBI: 926, H: 2,103, SB: 118

#52 William Harold “Memphis Bill” Terry

1B-OF, Giants, 1923–36. Hall of Fame, 1954

Terry hit .401 in 1930, which makes him the last National Leaguer to exceed .400. (Ted Williams did it 11 years later in the American League, batting .406.) His 250 hits that year are the second-best single-season total ever.

Terry was a great hitter in an era of very good batsmen. Three other times in his career, he hit .350 or better, and six times in his career, Terry had 200 hits or more. He also scored 100 or more runs seven different times.

He was an excellent defensive player, leading National League first basemen in putouts and double plays five times each, in assists three times and in fielding percentage twice.

He accomplished all this despite a relatively late start: Terry didn’t make the big leagues until he was 25 and didn’t become a regular with the Giants until he was 27. Terry was a productive player until the end of his career, hitting .310 as a part-time player-manager with the Giants in 1936.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .341, HR: 154, RBI: 1,078, H: 2,193, SB: 56

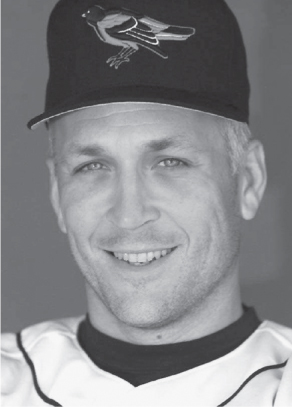

#53 Calvin Edwin “Cal,” “Iron Man” Ripken Jr.

SS-3B, Orioles, 1981–2001. Hall of Fame, 2007

The man who broke the “unbreakable” record, Ripken began his amazing streak in 1983 and didn’t miss a game until 18 years later. He played in 2,632 consecutive games, smashing Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,131. And, it’s fair to point out, Ripken played a vast majority of those games at shortstop, which, defensively, is a tougher position to play than first base.

But let’s not forget that the guy was also really good. He hit .300 or better five times in his career. He won the MVP award in 1983 and again in 1991. Twelve times in his career, Ripken belted 20 or more home runs, and he had 100 or more RBI four times.

On defense, Ripken won two Gold Gloves, in 1991 and 1992. In 1990, Ripken’s .996 fielding average was the best for a shortstop in baseball history. In fact, Ripken’s .990 fielding average in 1989 is fourth best all time and his .989 in 1995 is tied for eighth best all time. His career lifetime fielding average of .979 is fifth-best.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .276, HR: 431, RBI: 1,695, H: 3,184, SB: 36

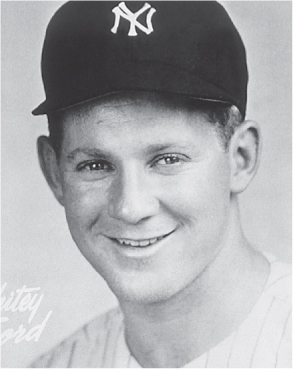

#54 Edward Charles “Whitey,” “The Chairman of the Board,” “Slick” Ford

LHP, Yankees, 1950–67. Hall of Fame, 1974

Whitey Ford pitched with a confident efficiency that made him one of the best “Big Game” pitchers in baseball history.

True, he played for a Yankee franchise that won 11 American League pennants and six World Championships in his tenure, but Ford’s forte was taking the ball in big games and winning those games. Easier said than done.

He remains the leader in World Series wins with 10, games started with 22, as well as innings pitched, strikeouts and losses. Over the span of the 1961, 1962 and 1963 World Series, he pitched 33 consecutive shutout innings, breaking Babe Ruth’s record of 29 2/3 innings with the Red Sox.

Ford’s ERA during the regular season with New York was under 3.00 a total of 11 times, and he was the league leader twice, in 1956 and 1958. In 1961, he went 25–4 with 209 strikeouts to win the Cy Young award.

Ford only won 20 or more games twice in his career, but was a player unimpressed by stats anyway. Winning was the stat he cared more about.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 236, L: 106, SV: 10, ERA: 2.75, SO: 1,956, CG: 156

#55 Edwin Donald “Duke,” “The Silver Fox” Snider

OF, Dodgers, Mets, Giants, 1947–64. Hall of Fame, 1980

Looking back, Duke Snider was probably considered the third-best of the three stellar center fielders who played in New York, after the Giants’ Willie Mays and the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle. But Dodger fans of the day will gladly point out that the Duke of Flatbush, as he was called, hit more home runs than Mays or Mantle in the four years (1954–57) that all three men were manning center field in the Big Apple for their respective teams.

Snider was a part-time player for the first two years of his existence as a Dodger, but apt tutoring by George Sisler enabled Snider to adjust his stance slightly to better enable him to drive balls up and out of tiny Ebbets Field. He hit 40 or more home runs five consecutive years, from 1953 to 1957, leading the league in 1956 with 43.

Snider was a strong defensive player, with a powerful throwing arm and excellent speed.

Snider was one of the best postseason players ever, setting National League records for home runs (11) and RBI (26). In the 1952 and again in the 1955 Fall Classic, Snider hit four home runs. He is the only man to do so twice in World Series history.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 407, RBI: 1,333, H: 2,116, SB: 99

#56 Steven Norman “Steve,” “Lefty” Carlton

LHP, Cardinals, Phillies, Giants, White Sox, Indians, Twins, 1965–88. Hall of Fame, 1994

Carlton is the number two lefthander of all time, in terms of wins, behind Warren Spahn, and the number two all-time in strikeouts, behind Nolan Ryan.

Interestingly, when Carlton first began trying out for big league teams, there was some question as to his arm strength. In response, Carlton became almost a fitness fanatic, and within a few years was one of the hardest throwers in the game.

He became a solid, dependable starter with the Cardinals in 1967 to 1968, going 27–20 as St. Louis won back-to-back National League pennants. But his persistent salary demands were wearing out the Cardinal front office, and he was traded to the Phillies.

That trade was the turning point in Carlton’s career. He became an instant star in Philadelphia, winning the Cy Young award four times while there: in 1972, 1977, 1980 and 1982. Carlton was the first pitcher to win four awards, although he has since been eclipsed by Roger Clemens, who has six.

That first Cy Young might have been the best. Carlton won 27 games for a team that won only 59 total. He led the league in complete games (30), innings pitched (346 1/3) and strikeouts (310), becoming only the second National League pitcher to amass more than 300 strikeouts in a season. (Sandy Koufax was the first.)

Carlton developed a devastating slider to go with his fastball and won the strikeout crown five times in all.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 329, L: 244, SV: 2, ERA: 3.22, SO: 4,136, CG: 254

#57 Walter Fenner “Buck” Leonard

1B-OF, Homestead Grays (Negro Leagues), 1934–50. Hall of Fame, 1972

Leonard was a left-handed pull hitter who was the anchor for the legendary Homestead Grays in the 1930s and 1940s.

He was born in North Carolina, the oldest of six children. His parents called him “Buddy,” but one of his younger brothers couldn’t pronounce that name very well, instead calling his older sibling “Buck.” The name stuck.

Leonard began his pro career playing in semipro Negro Leagues in North Carolina. But his fearsome hitting drew the attention of Cumberland “Cum” Posey, the manager-owner of the Grays. Leonard signed a contract to play for the Grays in the summer of 1933. For the next 17 years, he was the team’s starting first baseman.

Leonard was a very good hitter, recording team-leading batting averages of .356 in 1936, .396 in 1937, .397 in 1938, .394 in 1939 and .378 in 1940, as the Grays won the Negro National League five consecutive years. His .397 in 1938 also led the Negro National League.

In 1942, when catcher Josh Gibson joined Leonard and the Grays, the two men became known as the “Thunder Twins,” and led the Homesteads to three more NL titles, and Negro League World Series championships in 1943 and 1944.

Leonard was a solid defensive first baseman, described by observers at the time as being as agile as the legendary Hal Chase.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .335, HR: 79, H: 779,

#58 Louis Clark “Lou” Brock

OF, Cubs, Cardinals, 1961–79. Hall of Fame, 1985

Brock was a weak-hitting but explosively fast outfielder with the Cubs when, in 1964, he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Ernie Broglio. Broglio was a decent pitcher, but at the time, Brock was deemed a lousy outfielder. The conventional wisdom of the time was the Cardinals got snookered.

They didn’t. The trade galvanized Brock. He hit .348 with 33 stolen bases and 81 runs scored in 103 games for the Cardinals as St. Louis surged to the pennant and beat the Yankees in a stirring seven-game World Series. It is regarded as one of the worst trades ever, possibly the worst ever in the National League, and not far from the Ruth trade all-time.

Brock went on to become a feared leadoff hitter, even though his strikeouts were exceptionally high for a leadoff man. Still, he led the league in stolen bases eight times, including a National League record 118 in 1974, when Brock was 35.

He was sensational in the postseason, hitting .391 in three World Series, which is second all-time for players who played in two or more Fall Classics. In the 1967 and the 1968 Series, Brock hit over .400 both times.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .293, HR: 149, RBI: 900, H: 3,023, SB: 938

#59 William Malcolm “Bill” Dickey

C, Yankees, 1928–46. Hall of Fame, 1954

Dickey was the backbone of the Yankee powerhouses of the 1930s and early 1940s, a tough, durable, great-hitting catcher who hated to sit out games.

Dickey joined the Yankees in August of 1928 and played a handful of games. But by the next season, he was New York’s starting catcher. He hit .324 with 10 homers and 65 RBI. He struck out only 16 times in 447 at bats.

Dickey was a durable backstopper, catching 100 or more games in 13 consecutive seasons. He led the league’s catchers in fielding percentage four times and was second four other times.

He was also an excellent handler of pitchers. The Yankee pitching staff in those days ran the gamut from the eccentric Lefty Gomez to the ultra-competitive Red Ruffing, and Dickey commanded the respect of all of them.

He was a fearsome weapon for New York at the plate, as well. Dickey hit .300 or better 11 times in his career, and was a solid postseason batsman, twice hitting over .400 in the World Series, in 1932 and again in 1938.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .313, HR: 202, RBI: 1,209, H: 1,969, SB: 36

#60 Adrian Constantine “Cap,” “Pop” Anson

1B-3B-C-2B-OF, Rockford (NA), Philadelphia (NA), Cubs, 1871–97. Hall of Fame, 1939

Cap Anson might not have been the best baseball player of the 19th century, but he was the National League’s first real star, and its most visible presence for almost three decades.

Anson began his career in the old National Association, the forerunner of the National League. He hit .415 for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1872, and the next season, fell one hit short of that magic number, batting .398.

After he signed with the Chicago White Stockings (the forerunners of the Cubs) in 1876, Anson continued his superior batting, hitting .300 or better in 19 of his 22 National League seasons, including 15 years in a row. Anson won batting titles in 1881 and 1888.

Anson was as good a manager as a player. In 1879, he became player-manager in Chicago. Anson was one of the first managers to rotate his pitchers, devise hit-and-run plays and encourage base stealing. He was one of the first, if not the first, manager to require his players to report to their team early for preseason training.

The White Stockings won five pennants under Anson’s tenure in the 1880s, including three straight from 1880 to 1882.

The one mark against Anson was that he was clearly a racist. He once pulled his team off the field rather than play a team of blacks. But it may be a stretch to say that his influence kept blacks out of the majors until 1947.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .329, HR: 97, RBI: 1,879, H: 2,995, SB: 247

#61 James Thomas “Cool Papa” Bell

OF-1B, St. Louis Stars, Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Memphis Red Sox (Negro Leagues), 1922–42. Hall of Fame, 1974

The fastest man, probably, in baseball history. Some of the stories about Bell were almost certainly exaggerations, such as the time he slapped a single up the middle and was hit by his own batted ball, and the Satchel Paige–generated tale of Bell turning a light switch and scooting under the covers before the lights went out.

But others were not. He regularly took two bases on bunts down the first base line. Against a team of major league All Stars, onlookers watched in awe as Bell scored from second base on a sacrifice fly to right field.

Bell’s superior speed enabled him to hit high averages for most of his Negro League career. His teammates noticed how calm he was under even the most pressure-packed situation, and one of his first coaches commented that the 19-year-old Bell was “one cool papa.”

Bell was regularly among the league leaders in batting average, extra bases, stolen bases and runs scored. At least once he topped .400 during a Negro League season. That was in 1946; Bell, by then 43 years old, was hitting .402. But he sat out the last week of the season so that Monte Irvin would win the batting title and have a shot at the major leagues. Bell’s decision to sit also cost him a $200 bonus.

It’s no wonder Bell was so revered by his teammates. In 1951, Bell was approached by the St. Louis Browns of the American League to play for them. But Bell, at 48, turned them down, not wanting to possibly take a roster spot from another, younger, black hopeful.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .328, HR: 73, H: 1,561

#62 Gordon Stanley “Mickey,” “Black Mike” Cochrane

C, Athletics, Tigers, 1925–37. Hall of Fame, 1947

Cochrane’s “Black Mike” nickname came from when he was a multisport star (football, baseball) at Boston University. His extreme competitiveness rushed to the forefront if his team lost a close game and he would fall into an angry funk. He was, recalled one of his former college teammates, the wrong man to be around after a 1–0 loss.

That competitiveness didn’t disappear when he got to the big leagues. Cochrane was a great hitter, a great defensive catcher and a leader on every team on which he played.

Cochrane hit better than .300 in nine of the 13 years he was a major league player. He did not have overwhelming power and wasn’t an explosive runner, but he almost always put the ball in play and was nearly impossible to strike out. In 1929, he hit .331, with 170 hits in 514 at bats, and whiffed only eight times all year.

Cochrane twice hit for the cycle, in 1932 and again in 1933 with Philadelphia. In 1925, Cochrane hit three home runs in one game. He was named MVP in 1928 with Philadelphia and in 1933 with the Tigers.

Defensively, he led the league’s catchers in fielding percentage twice and assists six times, although he also led the league’s backstoppers in errors two other seasons.

He was a winner. Cochrane played in five World Series for two teams, winning three. He hit .400 in the 1929 Series against the Cubs.

Cochrane’s career was ended prematurely when he was beaned by Yankee pitcher Bump Hadley. But he went on to a solid career as a manager, scout and executive. Mutt Mantle named his oldest son, Mickey, after Cochrane.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .320, HR: 119, RBI: 832, H: 1,652, SB: 64

#63 Reginald Martinez “Reggie,” “Mr. October” Jackson

OF-DH, Athletics, Orioles, Yankees, Angels, 1967–87. Hall of Fame, 1993

Jackson’s outspoken behavior sometimes (well, actually most of the time) overshadowed a prodigious talent. He remains one of the better “big game” players in the history of the game.

Jackson played on 10 divisional championship teams, six pennant winners and five World Champions. Jackson’s batting average in five World Series is .357, almost 100 points better than his career average. His career World Series slugging average of .755 is still a record.

In 1977, he hit three home runs in the deciding game of the World Series, off three different pitchers on three consecutive pitches, perhaps one of the most dramatic performances in World Series history.

He wasn’t a slouch during the regular season, either. Jackson was MVP in 1973, when he led the American League in home runs (32), runs scored (99), RBI (117) and slugging percentage (.531). He led the league in round-trippers four times, in 1973, 1975, 1980 and 1982.

Jackson could also run the bases, stealing 20 or more four times in his career and averaging about 24 doubles per year for his career.

He struck out an awful lot, though, and his 2,597 whiffs are still the most ever.

He also had a big mouth. In 1977, when he was acquired by New York, he told a writer he was “the straw that stirred the drink,” which alienated teammate Thurman Munson and manager Billy Martin. He was, but there was no reason to trumpet the fact. Basically, Jackson’s philosophy was: It ain’t bragging if you can do it. And he could.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .262, HR: 563, RBI: 1,702, H: 2,584, SB: 228

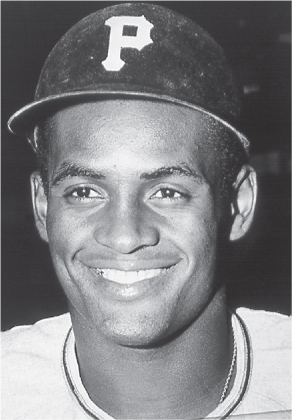

#64 Roberto Walker “Arriba” Clemente

OF, Pirates, 1955–72. Hall of Fame, 1973

Clemente was an outstanding defensive outfielder who was also one of the most consistent hitters of the 1950s and 1960s.

Clemente was noted more for his defensive abilities in the early part of his career. He had a strong, accurate throwing arm from the outfield, and his speed and athleticism enabled him to track down balls that would have eluded most defenders. He would go on to win 12 Gold Glove awards for his fielding and lead National League outfielders in assists five times.

Gradually, Clemente’s offensive abilities began to catch up with his defensive prowess, but it wasn’t until he won the first of four batting titles in 1961 (with a .351 average) that people began noticing that facet of his game.

In the 1960s, Roberto Clemente became a bona fide star, winning three more batting championships in 1964, 1965 and 1967, and the MVP award in 1966. Gradually, the Pirates were getting better, too.

Clemente’s showcase came in the 1971 World Series. He had played well in the 1960 Fall Classic with Pittsburgh, hitting .310 as the Pirates upset the Yankees. But in 1971, Clemente was amazing, hitting .414 and slugging .759 to become MVP of the Series as the Pirates defeated the Orioles in seven games.

On New Year’s Eve 1972, Clemente was on board a plane flying to Managua, Nicaragua, with relief supplies for earthquake victims there. His plane encountered turbulence, and crashed about a mile off the Puerto Rican coast. There were no survivors. The five-year waiting period for induction into the Hall of Fame was waived and Clemente was immediately inducted.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .317, HR: 240, RBI: 1,305, H: 3,000, SB: 83

#65 Henry Benjamin “Hammerin’ Hank” Greenberg

1B-OF, Tigers, 1930–41, 1945–47. Hall of Fame, 1956

A native New Yorker, Greenberg was initially deemed too big and clumsy to be a professional baseball player. But his hard work and persistence eventually paid off in spectacular fashion.

Greenberg was born in the Bronx, and while New York Giants manager John McGraw was always on the lookout for native New Yorkers who were also Jewish to expand his teams’ fan base, Greenberg was so uncoordinated as a teen that McGraw didn’t think he would make the cut.

Greenberg eventually signed with the Tigers in 1930, but it wasn’t until 1933 that he actually became a regular. Greenberg hit .301 in that first full season, with 12 home runs and 87 RBI. He belted line drives all over Tiger Stadium, and while he was still a little awkward, he was clearly going to be a good one.

Greenberg led the Tigers to back-to-back American League pennants in 1934 and 1935, which, in the New York Yankee–dominated 1930s, was a great accomplishment indeed. He hit .321 in a loss to the Cardinals in 1934. In 1935, Greenberg had an MVP year, with 36 home runs, 170 RBI and a .328 batting average.

His 1938 assault on Babe Ruth’s home run record in 1958 electrified Tiger fans, although Hank fell just short with 58. In 1940, he won another MVP award, this time after switching to the outfield.

He served four distinguished years in the military during World War II and upon his return in 1945, led the Tigers to another pennant. He hit .304 in Detroit’s World Series win over the Cubs.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .313, HR: 331, RBI: 1,276, H: 1,628, SB: 58

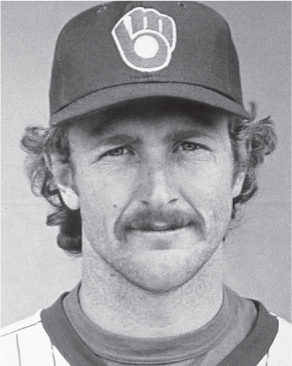

#66 Robin R. Yount

SS-OF, Brewers, 1974–93. Hall of Fame, 1999

Yount was only 18 when he started for the Brewers at shortstop in 1974. He learned quickly, cracking 28 doubles and 149 hits his second year in the bigs. By 1980, Yount was a star, leading the league with 49 doubles and 82 extra-base hits.

An aggressive weight-training regimen paid off in 1982, when his power numbers jumped. Yount hit 29 homers, 12 triples, a league-leading 46 doubles and scored 129 runs to earn the MVP award as the Brewers won the American League championship that year. Yount hit .414 in his only World Series appearance, a loss to the St. Louis Cardinals.

A shoulder injury forced the Brewers to move Yount to the outfield. He adapted well, hitting over .300 from 1986 to 1989. He won his second MVP award in 1989, hitting .318 with 195 hits, 21 home runs, 38 doubles and nine triples.

Yount was not particularly fast, but he was a smart base runner, stealing 15 or more bases nine times in his career.

Yount got his 3,000th hit at age 37, one of the youngest players ever to accomplish that feat.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, HR: 251, RBI: 1,406, H: 3,142, SB: 271

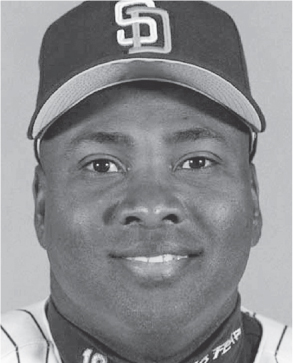

#67 Anthony Keith “Tony” Gwynn

OF-DH, Padres, 1982–2000. Hall of Fame, 2007

Gwynn parlayed a tremendous work ethic into becoming one of the great National League hitters of modern times. And he was no slouch in the outfield, either.

Gwynn was a third-round pick by the Padres in 1981, and came up to the big club a year later. He was also a first-round pick of the NBA’s San Diego Clippers. Gwynn hit .289 in limited action with San Diego, but his work ethic impressed his coaches.

In 1984, he became the first Padre to make more than 200 hits (he had 213) as well as the first San Diego player to win a batting title, with a .351 average. It was the first of eight batting titles for Gwynn. Only Ty Cobb has more crowns.

For several seasons in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Gwynn would get off to an explosive start, and sportswriters would speculate about his chances of hitting .400. Gwynn never made it, but in 1994, his .394 average was the best in the National League since Bill Terry’s .401 in 1930. It was the first of four consecutive batting championships for Gwynn.

Never much of a power hitter, Gwynn was an excellent base runner. He hit 21 or more doubles 16 consecutive years, and tied a record in 1986 with five stolen bases in one game. In 1987, he stole 56 bases, good for second in the league.

Originally a fair to poor fielder, Gwynn’s work ethic eventually earned him five Gold Gloves in the outfield.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .338, HR: 134, RBI: 1,121, H: 3,108, SB: 318

#68 Charles Leo “Gabby” Hartnett

C, Cubs, Giants, 1922–41. Hall of Fame, 1955

As a first-year player with the Cubs in 1922, Hartnett was shy around his new teammates, which led to his ironic nickname. But until Johnny Bench came along, Hartnett was considered the best catcher in the history of the National League.

His strength was fielding, and he led National League catchers in fielding percentage six times in his career, including a record-tying four consecutive times from 1934 to 1937. Hartnett also led the league in assists six times, in putouts four times and in double plays six times.

But Hartnett’s most famous moment came while at bat. On September 28, 1938, Hartnett was at bat against the Pirates in the bottom of the ninth, with the score 5–5 and two strikes on him. Hartnett had taken over management of the team at midseason, and the Cubs were charging toward a pennant, trailing Pittsburgh by a half-game at that point.

As darkness began to fall, Hartnett slammed a game-winning home run to put his team in first place. Three games later, the Cubs were National League champs, and the “Homer in the Gloamin’” was a part of baseball lore.

Hartnett was actually a pretty good hitter, so the home run was not a complete surprise. He hit .300 or better six times in his career, and won the MVP award in 1930 with a .339 batting average, 37 home runs and 122 RBI. The latter two stats were career highs.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .297, HR: 236, RBI: 1,179, H: 1,912, SB: 28

#69 Harmon Clayton “Killer,” “The Fat Kid” Killebrew

1B-3B-OF-DH, Senators, Twins, Royals, 1954–75. Hall of Fame, 1984

A tremendous power hitter, Harmon Killebrew played several positions with the Senators and Twins over his career, and always seemed to handle them pretty well. His forte was obviously at the plate, but Killebrew was fundamentally sound enough to play well wherever he had to.

He actually didn’t become a starter until his sixth year in the majors, and only then after an injury to infielder Pete Runnels. But that season, the Killer bashed 42 home runs to lead the league, the first of eight years he would hit 40 or more dingers.

His power was awesome. In 1962, he hit a ball completely out of vast Tiger Stadium. In 1967, his three-run blast shattered two seats in the upper deck of Minnesota’s Metropolitan Stadium. The seats were painted orange and never sold again.

Killebrew, for a while, seemed poised to break some of Babe Ruth’s home run records in the mid-1960s. But the muscular Minnesotan began suffering nagging injuries that usually didn’t sit him down, but did hamper his production.

Killebrew had his best season in 1969, and won the MVP award while hitting 49 home runs, with a 140 RBI, 145 walks and a .430 slugging percentage, all league bests. He also had 153 hits and stole a career-high eight bases.

He probably should have ended his career in Minnesota, but after a contract squabble, Killebrew found himself in Kansas City in 1975.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .256, HR: 573, RBI: 1,584, H: 2,086, SB: 19

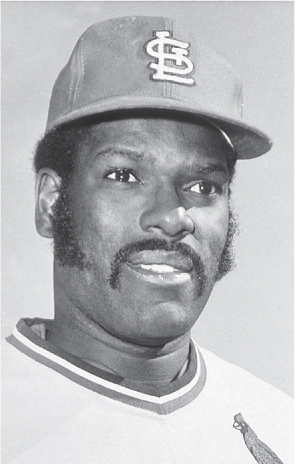

#70 Pack Robert “Bob,” “Hoot” Gibson

RHP, Cardinals, 1959–75. Hall of Fame, 1981

One of the best “money” pitchers ever, Gibson combined a fierce competitiveness with tremendous athleticism to become one of the premiere pitchers of the 1960s.

Gibson was a great pitcher in the regular season: He won 20 or more games five times in his career, and seven times he completed 20 or more games in a season.

But his World Series pitching was even more impressive. He won seven World Series games in a row, and those seven career victories are second only to the Yankees’ Whitey Ford. His World Series ERA is a minuscule 1.89 and he completed eight of his nine starts.

In 1968, he set a World Series record with 17 strikeouts in Game One of the series. He won the seventh game in both the 1964 and 1967 World Series.

Gibson’s 1968 season was one of the greatest seasons of all time. He went 22–9, with a league-leading 13 shutouts, completed 28 of his 34 starts, struck out a league-leading 268 batters and turned in an incredible 1.12 ERA, still the lowest of the 20th century for a pitcher throwing 300 innings or more. At one point, he allowed two runs in 92 innings. That effort earned him the Cy Young and Most Valuable Player awards. He would also win another Cy Young in 1970.

He was a great athlete, and fielded his position very well, earning nine Gold Gloves. A fierce competitor, he hated to come out of games. His catchers usually weren’t too thrilled to visit him on the mound during games, either.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 251, L: 174, SV: 6, ERA: 2.91, SO: 3,117, CG: 255

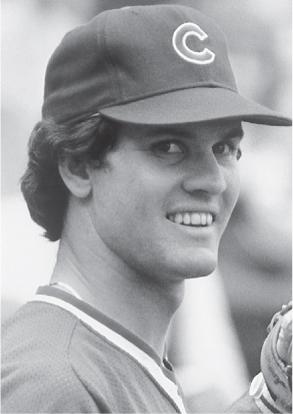

#71 Ryne Dee “Ryno” Sandberg

2B-3B-22, Phillies, Cubs, 1981–97. Hall of Fame, 2005

Sandberg, a benchwarmer for the Phillies at the time, was a throw-in in the deal that sent Ivan DeJesus from the Cubs. It turned out to be a stunning deal for Chicago, who acquired the best second baseman of the 1980s.

Sandberg was a tremendous all-around player. He was a great fielder, winning a record nine consecutive Gold Gloves at second base. In 1986, he set a record for the fewest errors (five) and highest fielding percentage ever, with a .994 mark. In all, Sandberg had the best fielding percentage for a second baseman four times in his career. In 1989, he went 91 games without an error at second base, another record.

As good as he was in the field, Sandberg was also quite accomplished at the plate. He hit .300 or better five times in his career, and had 20 or more doubles 13 times, 19 or more home runs eight times, scored 100 or more runs seven times and racked up 100 RBI twice. In 1984, his MVP season, he was a triple and a home run short of being the first player ever to have 200 hits and 20 or more doubles, triples, home runs and stolen bases.

In 1990, Sandberg had another top-shelf season, leading the league in home runs with 40, in runs scored with a league-leading 116, and hitting .306 with 30 doubles, 100 RBI and 25 stolen bases.

Sandberg was also one of the best-hitting Cubs in the postseason, hitting .385 in two League Championship series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, HR: 282, RBI: 1,061, H: 2,386, SB: 344

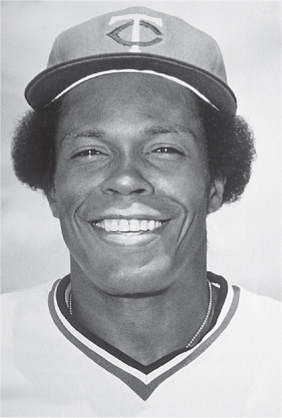

#72 Rodney Cline “Rod” Carew

1B-2B-DH, Twins, Angels, 1967–85. Hall of Fame, 1991

Carew was a hitting machine, turning in 15 consecutive .300 seasons in his 19-year career. Only Ty Cobb, Stan Musial and Honus Wagner ever exceeded that number.

In addition, Carew won seven batting titles, and won them by consistently larger margins than anyone in history except Rogers Hornsby. In 1977, the year he won the MVP Award, Carew hit .388. The next best average was Dave Parker’s .338, which won the National League batting title. That 50-point margin is the greatest gap between the best and second-best hitters in major league history.

In 1972, he became the first player in history to win a batting crown without hitting a home run. Carew hit for the cycle in 1970 and, in five separate games over his career, got five base hits.

Besides hitting, Carew was one of the best base runners ever. He stole home seven times in 1969, and on May 18 of that year, stole three bases in one inning. In addition, he was probably one of the best players ever at taking the extra base on a single or a double.

Carew was not an outstanding defensive player, but he was solid. A misconception that has persisted after his retirement was that he was moved from second base to first base in 1976 because of his defensive liabilities. Actually, he was moved there to prolong his career. He was named to 18 consecutive All Star games, although he missed two with injuries.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .328, HR: 92, RBI: 1,015, H: 3,053, SB: 353

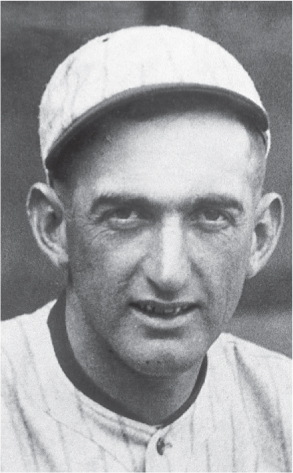

#73 Joseph Jefferson “Shoeless Joe” Jackson

OF, Athletics, Indians, White Sox, 1908–20

Did he? Didn’t he? We may never know for sure if Shoeless Joe Jackson conspired, with seven other members of the Chicago Black Sox, to throw the 1919 World Series. From most of the evidence, it seems as though Jackson may have tried to have the best of both worlds, accepting money to fix the series, but playing as hard as he could to win it.

At any rate, Jackson, with his ebony bat, “Black Betsy,” was a superior hitter, making a career-high .408 in 1911, and following that up with a .395 average in 1912 and .373 in 1913. Babe Ruth reportedly patterned his swing after Jackson’s.

Jackson was also a good base runner—fast, with excellent instincts. He stole 20 or more bases five times in his career and led the league in triples three times and doubles once.

Jackson played all three outfield positions in his career. He was second in assists and putouts in 1912 and assists in 1913 while playing right field for the Indians. While playing left field for the White Sox, he was second in putouts in 1917 and third in assists in 1919.

After a superior season in 1920 (218 hits, 42 doubles, a league-leading 20 triples, 12 home runs, 121 RBI and a .382 average), the betting scandal hit, and Jackson was banned from baseball for life.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .356, HR: 54, RBI: 785, H: 1,772, SB: 202

#74 George “Mule” Suttles

1B-OF, Birmingham Black Barons, St. Louis Stars, Baltimore Black Sox, Detroit Wolves, Washington Pilots, Cole’s American Giants, Newark Eagles, Indianapolis ABCs, New York Black Yankees (Negro Leagues), 1918–44. Hall of Fame, 2006

Suttles, at 6' 3", 215 pounds, was one of the great power hitters in Negro League history. Called “The Mule” because of his strength and penchant for carrying teams when he went on one of his typical hot streaks, Suttles played professionally for 26 seasons.

For most of his career, Suttles wielded a huge 50-ounce bat, with which he belted long home runs to all fields. He hit several legendary home runs, including a blast in an exhibition game in Cuba in 1930 that carried more than 600 feet, startling a squad of cavalrymen on horseback who were at the field to prevent trespassers coming in from that part of the ballpark.

Suttles often hit home runs in bunches. Reportedly, in 1929, while playing with the St. Louis Stars against the Memphis Red Sox, Suttles hit three home runs in one inning in a 26–4 rout. His best season was 1926, when he batted .413, with 26 home runs and a hard-to-believe 1.000 slugging average. Records are incomplete, but Suttles is believed to be the career home run leader in the Negro Leagues with 237.

Suttles was a fan favorite in St. Louis, with whom he won league championships in 1928, 1930 and 1931. When he came to bat, fans in the stands would yell, “Kick, Mule!” exhorting Suttles to hit a home run.

Suttles was often at his best in All Star games against white big leaguers. He hit .374 in 10 such contests, including a game against the Chicago Cubs in 1934 in which he hit a single, double and a triple in four at bats.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .341, HR: 237, H: 1,103

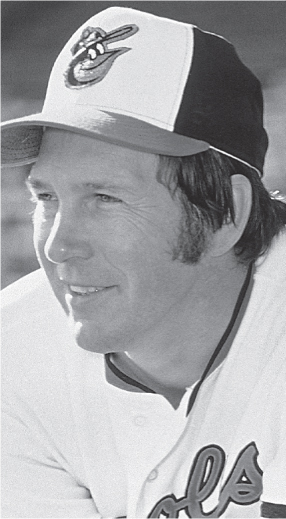

#75 Brooks Calbert “Brooksie,” “The Human Vacuum Cleaner” Robinson

3B-2B-SS, Orioles, 1955–77. Hall of Fame, 1983

Robinson was called “Brooksie” by his teammates and Oriole fans, but his unofficial nickname was “The Human Vacuum Cleaner” for his uncanny fielding abilities.

Robinson’s play has set the standard to which all third basemen aspire. He won 16 consecutive Gold Gloves in his 23 years at third base. He led American League third basemen in fielding 11 times, including nine of 10 years from 1960–69 (the Tigers’ immortal Don Wert beat him out in 1965). He led the league’s third basemen in assists eight times and was a 15-time All Star.

Robinson didn’t play baseball in high school, and was discovered by the Orioles playing in a church league. He sat on the bench for three years before becoming a regular in 1958. He was not an outstanding hitter, but he hit 20 or more home runs six times, batted .280 or better seven times and stroked 25 or more doubles 11 times in his career. In 1964, he hit .317, drove in a league-leading 118 runs and had 194 hits to win the MVP award.

His postseason performances have been legendary. Twice in League Championship Series in 1969 and 1970, he hit over .500. In the 1970 World Series, Robinson hit .429 and slugged .810 to win the MVP award (which included a late-model sedan) as Baltimore dominated a very good Cincinnati Reds team. “If we knew he wanted a car that badly,” said Reds catcher Johnny Bench, “we’d have bought him one.”

Robinson is the all-time leader at third base in games played with 2,870, fielding average with a .971 mark, putouts with 2,697, double plays with 618 and assists with 6,205.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .267, HR: 268, RBI: 1,357, H: 2,848, SB: 28