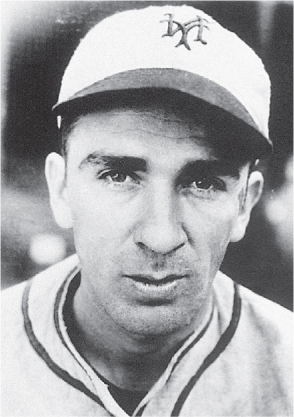

#76 John Franklin “Home Run” Baker

3B, A’s, Yankees, 1908–14, 1916–19, 1921–22. Hall of Fame, 1955

Baker was not the fence-buster that players like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig would be less than a decade after his retirement, but he did lead the American League in home runs four years running, from 1911 to 1914. His highest total for a season in that span was 12.

But actually, Baker earned his nickname when he hit two key home runs in successive games in the 1911 World Series. The first homer was a two-run shot of future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard in the sixth inning of Game Two to give Baker’s Athletics a 3–1 win. The next day, Baker’s ninth-inning home run off another future Hall of Fame pitcher, Christy Mathewson, tied the game 1–1, and Philadelphia won in extra innings.

Baker was much more than a home run hitter. He was the third baseman in the Athletics’ “$100,000" infield, along with shortstop Stuffy McInnins, second baseman Eddie Collin and first sacker Jack Barry. Baker led American League third basemen in fielding percentage twice in 1911 and again in 1918. He also led the league in assists and putouts twice, and in double plays three times.

He was a very good base runner, stealing 20 or more bases five times in his career, and also hit 10 or more triples five times in his career. In 1909, his 19 triples led the majors.

Baker was a great clutch player. His career average in World Series games is .363, fifth best of players who played in two or more Series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .307, HR: 96, RBI: 987, H: 1,838, SB: 235

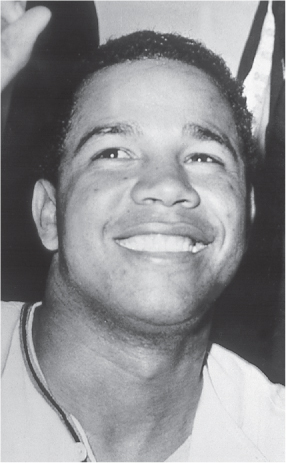

#77 George Kenneth “The Kid” Griffey Jr.

OF-DH, Mariners, Reds, White Sox, 1989–2010. Hall of Fame, 2016

For a majority of his 11 years with the Seattle Mariners, “Junior” was almost surely the best player in the game. But in 2000, after signing with the Reds, he had one injury-plagued season after another for the next several years.

Griffey broke in with Seattle as a baby-faced 19-year-old in 1989 and had a solid season, with 120 hits in 127 games, 23 doubles and 16 home runs. By the next year, he was a star, winning the first of 10 Gold Gloves in the outfield, hitting .300, with 22 home runs and 80 RBI.

He became the cornerstone of the Mariner franchise. Griffey has hit 40 or more home runs seven times, and in 1997 and 1998, he had back-to-back seasons of 56 homers. He was the American League MVP in 1997, combining the aforementioned 56 dingers with a .304 average, 34 doubles and a league-leading 125 runs scored on top of 147 RBI and 393 total bases.

Griffey has scored 100 or more runs six times, hit .300 or better, and had 100 or more RBI eight times. He was a consistent MVP candidate in the 1990s.

The 21st century hasn’t yet treated Griffey as well. From 2002 to 2004, he averaged about 72 games a year. The next two years were a little better, but 2007 has been his healthiest year by far. He had 23 homers and 59 RBI by the All Star break, and baseball fans hope this is a sign of future things to come.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .284, HR: 630, RBI: 1,836, H: 2,781, SB: 184

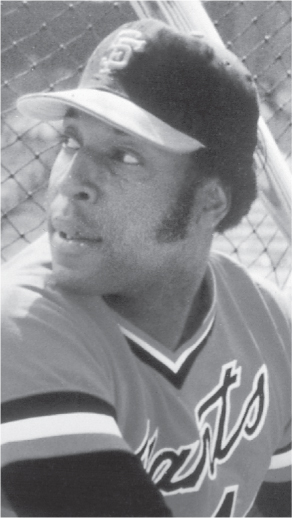

#78 Willie Lee “Mac,” “Big Mac,” “Stretch” McCovey

1B-OF-DH, Giants, Padres, Athletics, 1959–80. Hall of Fame, 1986

McCovey’s major league debut with the San Francisco Giants in 1959 was an impressive one: 4-for-4 with two singles and two triples against future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts. McCovey didn’t actually get into a game until the end of July, but despite playing only 52 games, he was still named Rookie of the Year, with a .354 average, and 13 home runs and nine triples in 52 games.

McCovey became a regular in the outfield, as the Giants already had a great first baseman in Orlando Cepeda. But in 1965, when Cepeda was felled by an injury, McCovey moved over to first and remained there for the rest of his time with the Giants.

McCovey, at 6'4", 210 pounds, was a tremendous physical specimen, and his home runs were usually explosive shots that got out of the park in a hurry. He won three home run crowns, in 1963 with 44, 1968 with 36 and 1969 with 45. The latter year, McCovey won the MVP award, with a league-leading 126 RBI, 26 doubles, 121 walks, 101 runs scored and a league-leading .656 slugging percentage.

McCovey is the only man to hit two homers in one inning twice in his career, in 1973 and again in 1977, but he is best known for a ball he hit that made an out. In the 1961 World Series, in the bottom of the ninth inning, with two outs, runners on second and third and trailing 1–0, McCovey hit a line drive that Yankee second baseman Bobby Richardson speared to end the game. It was, said McCovey, the hardest-hit ball he had ever struck.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .270, HR: 521, RBI: 1,555, H: 2,211, SB: 26

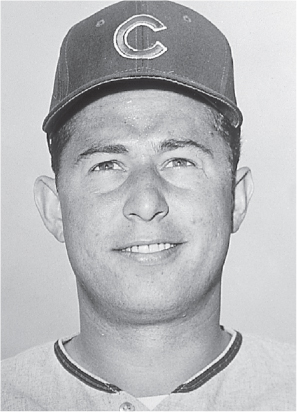

#79 Ronald Edward “Ron” Santo

3B-DH, Cubs, White Sox, 1960–74. Hall of Fame, 2012

Overshadowed by Brooks Robinson in the National League, Santo was nonetheless the best all-around third baseman in the National League throughout the 1960s. He won five consecutive Gold Gloves, from 1964 to 1968. Santo also led National League third basemen in putouts seven times, in double plays six times and in assists seven times. In 1964, he set a record (since broken) of assists by a third baseman with 367.

But Santo could also hit. He was not thought to be a power hitter, but Santo hit 25 or more home runs and drove in 90 or more runs in eight consecutive seasons, some of those years on Cubs teams that were notorious for their lack of hitting ability.

Santo led the league in bases on balls four times, but paradoxically, also struck out more than 100 times a season four times.

He was an intense guy, and was often very emotional after a big win or a tough loss. But Cub fans loved him for that and forgave some of his outbursts against umpires whom Santo thought might have given Chicago short shrift.

Oddly, Santo is best known for a quirky mannerism he displayed in 1969. As the Cubs began to make their ill-fated run toward a pennant, Santo would jump up and click his heels after every win.

Initially, it was simply a manifestation of his enthusiasm for finally being on a winning team. But of course, after a while, the fans demanded it, and other teams began to resent the move. It was all moot, of course, as Chicago fell short that year.

Santo died a few months after his election to the Hall of Fame. His election, in the eyes of many, was long overdue.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .277, HR: 342, RBI: 1,331, H: 2,254, SB: 35

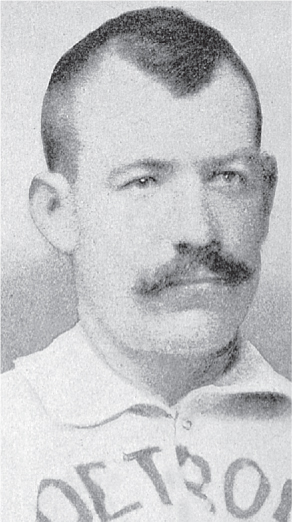

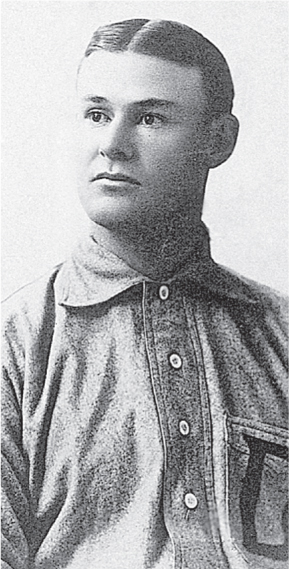

#80 Dennis Joseph “Big Dan” Brouthers

1B-OF, Troy Trojans (NL), Buffalo Bisons (NL), Detroit Wolverines (NL), Boston Braves (NL), Boston Red Stockings (PL), Boston (AA), Baltimore Orioles (NL), Louisville Grays (NL), Phillies, Giants, 1879–1904. Hall of Fame, 1945

Brouthers was a big fellow for his era, at 6'2", 207 pounds, and his big left-handed swing produced lots of hard hits and home runs for 10 teams over his long career.

Brouthers began his career with Troy, and was actually tried at pitcher for a few unsuccessful starts (0–2, 7.53 ERA) before being switched to first base, where he played most of his career.

Brouthers was traded to Buffalo in 1881, and led the league with eight home runs and a .541 slugging average. It was the first of seven years that Brouthers would lead the league in slugging percentage.

Brouthers won his first batting title, with a .368 mark, the next year. He would go on to win five batting titles, two home run crowns, top the league in hits three times, doubles three times and triples once.

In that 1882 season, he also led the league in slugging percentage with a .547 mark, on-base percentage with a .403 mark, hits with 129 and also was the top fielding first baseman in the league with a .974 percentage.

Brouthers was a strong defensive player, but he made his money at the plate. He went 6-for-6 in a game in 1883, and in 1886, he hit three home runs, a double and a single for 15 total bases.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .342, HR: 106, RBI: 1,296, H: 2,367, SB: 256

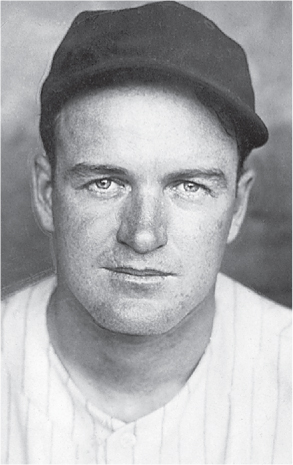

#81 Joseph Edward “Joe” Cronin

SS-3B-1B, Pirates, Senators, Red Sox, 1926–45. Hall of Fame, 1956

The Washington Senators seemed to have unusually good luck with “boy wonder” managers. First it was a young Bucky Harris who piloted the Senators to the 1924 pennant and in 1933, it was 26-year-old player-manager Joe Cronin.

Cronin was a better player than Harris, though. He was a hard-hitting shortstop who came up through the Pittsburgh organization before being sold to Washington in 1928. There, Cronin blossomed. In 1930, he hit .346 and had 126 RBI, both career highs.

Cronin was tough and smart, and in 1933, Senators’ owner Clark Griffith made him manager. He responded by leading Washington to its last American League pennant. They lost the World Series to the Giants in five games, but Cronin played well, hitting .318.

Cronin met Griffith’s niece (not his daughter, as is often reported) Mildred Robertson, who was a club secretary, at the beginning of the 1934 season. They fell in love and were married later that year. Griffith did sell Cronin to the Red Sox after the season, but Joe was his nephew-in-law, not his son-in-law.

Regardless, Cronin thrived in Fenway Park, hitting .300 or better seven times, slugging .500 or better four times and driving in 90 or more runs six times. He eventually sat himself down in 1942 to make room for budding Sox star Johnny Pesky, but he was still a fearsome pinch hitter for Boston for years.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .301, HR: 170, RBI: 1,424, H: 2,285, SB: 87

#82 Wade Anthony “Chicken Man” Boggs

3B-DH, Red Sox, Yankees, Devil Rays, 1982–99. Hall of Fame, 2005

Wade Boggs was a hitting machine for the Boston Red Sox in the 1980s and early 1990s. He had a beautiful, level swing, a superior eye for pitches in the strike zone and the patience to wait for the pitch he wanted to hit.

Boggs was mired for six years in the Red Sox minor league system, apparently because he was an indifferent fielder. But when he finally made it to Boston in 1982, Boggs was an immediate star, hitting a rookie record .349 with 118 hits in just 104 games.

In 1983, Boggs won his first batting title, hitting .361 with 210 hits, 100 runs scored, 44 doubles and 74 RBI. It was the first of seven consecutive years that he would go on to record 200 or more hits and 100 or more runs.

From 1983 to 1988, Boggs won the American League batting championship five of six years. In 1985, he led the league with 240 hits and a .368 batting average. He reached base 340 times that year, a feat only Babe Ruth, Ted Williams and Lou Gehrig have accomplished.

And his fielding improved, as well. In 1993 and 1995, while playing third base for the Yankees, he was the top fielding third baseman in the league. Boggs won back-to-back Gold Glove awards in 1994 and 1995.

Much was made of his metronome-like habits. His diet during the season was almost exclusively chicken, he took batting practice at 7:17 every night, and he walked to and from the dugout along exactly the same route. That intense concentration was clearly a key factor in Boggs’ success.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .328, HR: 118, RBI: 1,014, H: 3,010, SB: 24

#83 Carl Owen “King Carl,” “The Meal Ticket” Hubbell

LHP, Giants, 1928–43. Hall of Fame, 1947

The nicknames alone give you a hint of how good this guy was. Hubbell, an affable Oklahoman, won 20 games or more five years in a row for the Giants between 1933 and 1937. He was the National League MVP in both 1933 and 1936, the only non-wartime pitcher to do that in baseball history (Hal Newhouser did it with Detroit in 1944 and 1945).

Hubbell was a seven-time All Star, and the game for which he is best known was the 1934 All Star Game. After giving up a single to Charley Gehringer in the first inning, Hubbell then walked Heinie Manush. He then proceeded to strike out Babe Ruth (looking), Lou Gehrig (swinging) and Jimmie Foxx (swinging). He came back in the second inning and punched out Joe Cronin (swinging) and Al Simmons (swinging). That’s five Hall of Famers in a row, which has got to be some kind of record.

Hubbell’s left arm, by the end of his career, was twisted almost completely around by the action of throwing tens of thousands of screwballs.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 253, L: 154, SV: 33, ERA: 2.98, SO: 1,677

#84 Aloysius Harry “Bucketfoot Al” Simmons

OF, Athletics, White Sox, Tigers, Senators, Braves, Reds, Red Sox, 1924–44. Hall of Fame, 1953

Simmons was born Aloys Szymanski in the Polish section of Milwaukee. He Americanized his name when he began to play baseball, but was always proud of his Eastern European heritage.

Simmons was nicknamed “Bucketfoot Al” because he strode into the plate as he swung, his mannerism apparently resembling a man placing his foot in a bucket. It was fundamentally unsound, but his first manager, Connie Mack of the Athletics, wouldn’t allow any of his coaches to change it, because Simmons was clearly a very effective hitter.

Simmons’s secret may have been that his long arms and longer than usual bat enabled him to reach pitches at the other side of the plate easier than most.

Simmons had several great years with the star-studded Athletics, winning batting titles in 1930 and 1931, with averages of .381 and .390, respectively. He also led the league’s outfielders in fielding percentage in 1936.

When Mack began selling off his stars to pay the bills, Simmons was sent to the White Sox. The Polish Simmons was adopted by Chicago fans, and played in three All Star games while in the Windy City. He played for eight more teams in the next seven years, and ended his career back in Philadelphia in 1944.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .334, HR: 307, RBI: 1,827, H: 2,927, SB: 88

#85 Gregory Alan “Greg” Maddux

RHP, Cubs, Braves, Dodgers, Padres, 1986–2008. Hall of Fame, 2014

Arguably the best pitcher of the 1990s and one of the best in this century, Maddux was a 16-time Gold Glove winner and the only man in baseball history to win four consecutive Cy Young awards, from 1992 to 1995. He earned his first “Cy” while toiling for Chicago, and the next three were won while pitching for the Braves.

Maddux is called “The Thinking Man’s Pitcher,” because he does not have an overpowering fastball. Yet he has found success by changing speeds well and pitching with exceptional control. He led the Braves to the 1995 World Championship over the Indians.

Maddux is also durable, known as an “inning eater” because, even now, he often pitches into the seventh and eighth innings. He has thrown for 200 or more innings 18 times in his career.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 355, L: 227, SV: 0, ERA: 3.09, SO: 3,371, CG: 109

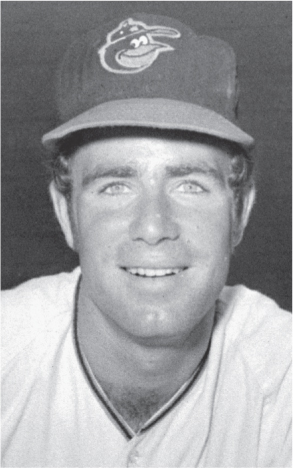

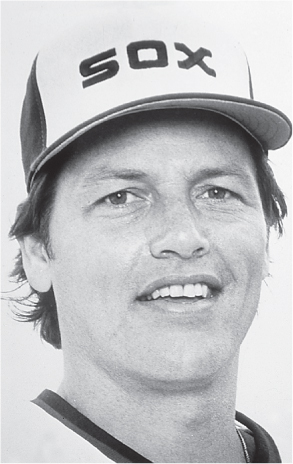

#86 James Alvin “Jim,” “Jockstrap Jim,” “Cakes” Palmer

RHP, Orioles, 1965–67, 1969–84. Hall of Fame, 1990

Palmer played his entire career with the Orioles, and is Baltimore’s greatest pitcher. But for the first four years of his career, he battled arm and back injuries that threatened to end that career.

Palmer was 23–15 in his first three years, but injuries forced him back to the minor leagues in 1968. Surgery and rehabilitation in the Instructional League helped him regain his form. Less than a week after he was called up in 1969, Palmer no-hit the Oakland A’s.

For the next decade, except for an injury-filled 1974, Palmer was one of the most consistent hurlers in baseball. He won 20 or more games eight times. Only Walter Johnson had more 20-win seasons in the American League, with 12. Twelve times, Palmer struck out more than 100 batters and he pitched 300 or more innings four times.

Palmer won three Cy Young awards, in 1973, 1975 and 1976. He was also an excellent fielder, winning four Gold Gloves from 1976 to 1979.

Palmer was a legitimate big game pitcher. He participated in six American League Championship Series, and had a 4–1 mark with a 1.96 ERA. He also pitched in six World Series, and was 4–2 with 44 strikeouts in 64 innings.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 268, L: 152, SV: 4, ERA: 2.86, SO: 2,212, CG: 211

#87 Joseph “Smokey Joe” Williams

RHP, Chicago Giants, New York Lincoln Giants, Chicago American Giants, Atlantic City Bacharach Giants, Hilldale Daisies, Homestead Grays, Detroit Wolves (Negro Leagues), 1905–32. Hall of Fame, 1999

Williams, a lanky 6'4" fireballer from Texas, was the first real pitching star in the Negro Leagues. Armed with a hellacious fastball, Williams set all kinds of strikeout records for the various teams on which he played.

Williams had at least a dozen 20-strikeout games over his career, including a classic battle against the Kansas City Monarchs’ Chet Brewer in 1930, when, as the starter for the Homestead Grays, William struck out 25 men in a 12-inning game in a 1–0 win. Brewer didn’t do too bad either, striking out 19 men.

Prior to that, his most famous game was in 1917, when he no-hit the New York Giants of the National League in an exhibition game, although he lost the game 1–0 on an error. But it was reportedly that day that Giant star Ross Youngs dubbed Williams “Smokey Joe.”

Williams reportedly had his best game against white major leaguers; his record against big-league clubs is 8-4. He also shut out the Giants in 1912, 6–0, on three hits, a few weeks after they lost the World Series to the Boston Red Sox, and, coincidentally, another “Smokey Joe,” this pitcher being Boston’s “Smokey Joe” Wood.

Wood was also an excellent batter, and at least twice hit better than .300 in a season.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 107, L: 57

#88 John Robert “Johnny,” “The Big Cat” Mize

1B-OF, Cardinals, Giants, Yankees, 1936–53. Hall of Fame, 1981

Mize, called “The Big Cat” because he was, well, a pretty big cat, was a rarity in pro baseball: a slugger who was also a great contact hitter.

Twice in his career, Mize led the league in home runs, but had fewer strikeouts than dingers, a remarkable feat. In 1947, Mize led the league with 51 homers and struck out only 42 times in 586 at bats. In 1948, Mize struck a league-leading 40 home runs and struck out only 37 times. In all, Mize would claim four home run crowns and a batting title in 1939, and lead the league in RBI three times.

Mize is the only man to hit three home runs in a game six times. He also hit two home runs in 30 games. Mize had seven pinch-hit home runs in his career.

Mize was a four-time All Star for the Cardinals and a five-time All Star for the Giants, but in 1949, he was traded to the Yankees. From 1949 to 1953, Mize was a part-time first baseman and pinch hitter for the Bronx Bombers, and all five of those teams won pennants and subsequently won World Series.

He hit .286 in the five championship series, and was the World Series MVP in 1952, hitting three home runs and batting .400 as the Yankees beat the Dodgers.

Considered awkward, Mize was actually a graceful fielder, leading the league’s first basemen in fielding twice, in 1942 and 1947.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .312, HR: 359, RBI: 1,337, H: 2,011, SB: 28

#89 Derek “Mr. November,” “The Captain” Sanderson Jeter

SS, Yankees, 1995–2014

Is Derek Jeter the greatest Yankee? Wow. What about DiMaggio, Mantle, Ruth? Lou Gehrig? Yogi Berra?

Well, to tell the truth, they are all above Jeter in the mythical Yankee pantheon. But, as the saying goes, he’s in good company.

Except for DiMaggio, Jeter has been the most consistent Yankee. Except for Gehrig, the most durable. Except for Ruth and Mantle, the best in the clutch. Except for Berra, the best teammate.

So not the best, but not too far from the top. The best modern-day Yankee regular and one of the great postseason performers, in any sport, of this generation. The fourteen-time All-Star has played in 33 postseason series, including seven World Series. Ten times in these individual series, Jeter hit .400 or better. Twice he hit .500. In 15 series, his on-base percentage was .400 or better. He has 200 hits in the postseason, 20 home runs and 61 RBI, with a .308 batting average.

Jeter is a 14-time All-Star, the 2000 World Series MVP, and a five-time Gold Glove winner. All those things are fine, but he has always said the five rings he has earned have always been his most prized possessions.

And that, of course, is what makes him a great player.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .310, HR: 260, RBI: 1,311, H: 3,465, SB: 358

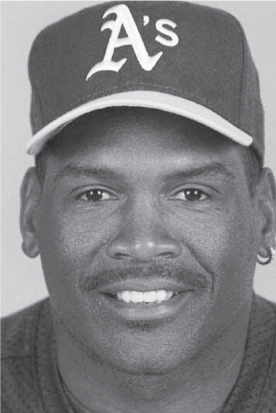

#90 Timothy “Tim,” “Rock” Raines

OF-DH, Expos, White Sox, Yankees, Athletics, Orioles, Marlins, 1979–99, 2001–02

When the lighting-fast Raines came up with the Montreal Expos, he was an explosive base-stealer who could change games without getting a hit. He led the league in stolen bases from 1981 to 1984 and was second in 1985 and third in 1986, averaging an eye-popping 76 thefts a year in that span.

The switch-hitting Raines was an excellent leadoff hitter, scoring 90 or more runs eight times and leading the league in that department twice. His 808 steals are fifth all-time. Raines won the batting championship in 1986. He hit .300 or better eight times in his career.

Raines was also a pretty patient man at the plate. He drew 80 or more walks seven times in his career. His 1,330 walks are 29th all-time.

Following a 12-year stint with the Expos, Raines was signed by the White Sox in 1991. By 1994, he was a part-time player for Chicago, but he was still a good hitter, if not as effective a base-stealer as he had been. Raines became a part-time player with the Yankees from 1996–1998 and seemingly finished up his career with the Oakland Athletics in 1999. But he made a comeback in 2001 with the Expos and did pretty well, hitting .308 in part-time play. He was traded to the Orioles that year and finally retired in 2002 after a year with the Florida Marlins.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .294, HR: 170, RBI: 980, H: 2,605, SB: 808

#91 Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean

RHP, Cardinals, Cubs, 1930, 1932–41, 1947. Hall of Fame, 1953

Dean was given his nickname by an unsympathetic sergeant in the U.S. Army, who had little patience for Private Dean’s shenanigans. Dean came up to the Cardinals on the last day of the season in 1930 and tossed a complete-game three-hitter.

Despite that performance, Dean didn’t get another chance with St. Louis until 1932, when he made the Opening Day roster. But he showed the Cardinals he was worth it, winning 18 games and leading the league in innings pitched, strikeouts and shutouts.

For the next four years, Dean was the best pitcher in baseball, by a country mile. He averaged 27 wins, 25 complete games, 311 innings pitched, 197 strikeouts, four shutouts, 50 starts and even seven saves a season over that span. Batters hit .252 against him and he walked a little fewer than two batters a game over that span. It is one of the most overpowering four-year stretches in baseball history.

In 1933, Dean struck out 17 batters in a game against the Cubs, a major league record at the time. Dean won the MVP award in 1934, and came in second the next two years.

In 1937, Dean, the starter for the National League in the All Star game, was hit in the foot by a line drive off the bat of Earl Averill. Dean sat out the first few weeks of the second half of the season but tried to come back too early. To compensate for his injured foot, Dean changed his delivery and suffered bursitis in his pitching arm.

The following year, Dean was traded to the Cubs, and became a spot starter, winning seven of eight games and helping Chicago to the National League pennant. But he would win only nine more games in his career.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 150, L: 83, SV: 30, ERA: 3.02, SO: 1,163, CG: 154

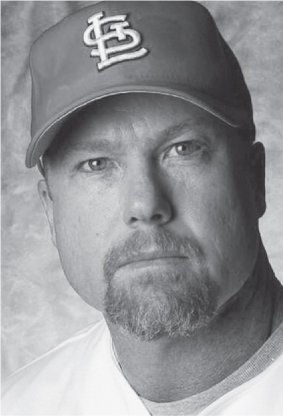

#92 Mark David “Big Mac,” “Sack” McGwire

1B-3B, Athletics, Cardinals, 1986–2000

McGwire became a home run hitting machine in the latter part of his career, hitting 135 dingers in a two-year span, from 1998 to 1999.

There is some speculation that the 6'5", 225-pound McGwire may have enhanced his already hefty frame with steroid use, but frankly, that’s all it is: speculation.

Regardless of whether or not his performances were “juiced,” McGwire was a most gracious home run champion. In 1998, when he was on track to best the 37-year-old record of 61 home runs by former great Roger Maris, McGwire invited the Maris family to be his guests (Maris died in 1985) for the several days it took to hit his 62nd, and when that moment finally came, McGwire dutifully acknowledged Maris. McGwire went on, of course, to hit 70 homers that year.

It’s also easy to forget that McGwire won two home run crowns before his 70 homers in 1998 and 65 in 1999. He cracked 49 homers in his second year with the Athletics in 1987 and hit 52 with Oakland in 1996.

McGwire came up with the Athletics, and was always a big swinger. He had 100 or more strikeouts in eight seasons, including a whopping 155 the year he hit 70 home runs. But he also led the league in bases on balls twice, and had more than 100 walks four times in his career.

McGwire was relatively slow afoot, with only six career triples and 12 career stolen bases. But his supporters will argue that he was not paid to steal bases, McGwire was paid to hit the ball out of the park, which he did with regularity.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .263, HR: 583, RBI: 1,414, H: 1,626, SB: 12

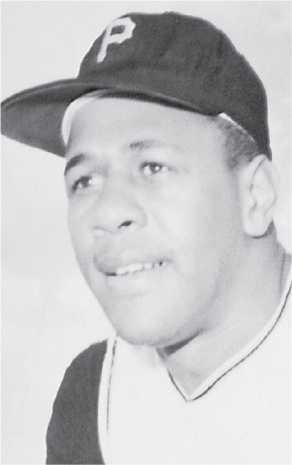

#93 Wilver Dornel “Willie” Stargell

OF-1B, Pirates, 1962–82. Hall of Fame, 1988

Slugger Stargell was a fearsome opponent at the plate, looming over the batter’s box, whipping his bat forward and back, forward and back, waiting almost eagerly for the next pitch.

Stargell was a big, powerful man at 6'2", 225 pounds. He belted some tape-measure home runs, including seven that carried over the right-field roof at Forbes Field, and the only two home runs ever hit out of Dodger Stadium.

A quiet, classy ballplayer, Stargell played, willingly, in the shadow of Pirate star Roberto Clemente for 10 years. But he became the Pirates’ team leader after Clemente’s sudden, stunning death in 1971. In 1979, Stargell won the MVP award in leading Pittsburgh to another World Series triumph over the Orioles.

Stargell’s numbers that year were not overpowering: 32 home runs, 82 RBI, a .281 batting average. But he seemed to clock a majority of the key hits for Pittsburgh in the regular season. And in the World Series, Stargell killed Baltimore, with a .400 batting average, four doubles, three home runs and seven RBI. He was the leader of the Pirates’ family, and the team song was “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge.

Thus, in addition to his MVP in the regular season, Stargell was the MVP of the National League Playoff Series against the Reds, the MVP of the World Series, The Sporting News Man of the Year and Sports Illustrated’s co-sportsman of the year with the Steelers’ Terry Bradshaw.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .282, HR: 475, RBI: 1,540, H: 2,232, SB: 17

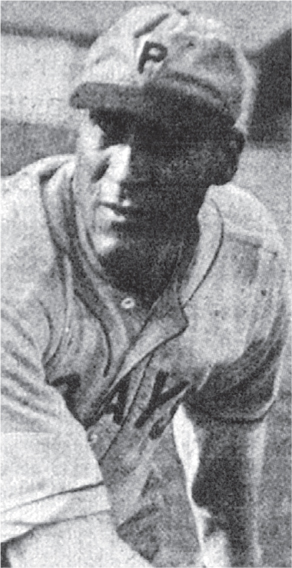

#94 Paul Glee “Big Poison” Waner

OF, Pirates, Dodgers, Braves, Yankees, 1926–45. Hall of Fame, 1952

Waner was one of the original party boys, a man who went out and painted the town red at night, and then got up and slapped a few extra base hits the next day to win the ball game. One story has it that Waner, late in his career, announced he was going on the wagon. He started the season hitting .250, and one of his coaches personally brought him over to a speakeasy to get him back on track.

As a rookie in 1926, Waner hit .336 and led the league with 22 triples. The next season, he was signed by Pittsburgh. Paul Waner won the first of three batting crowns with a career-high .380 average, and won the MVP award as Pittsburgh won the National League crown. The Pirates were creamed by the Yankees that year in four games, but Paul hit .333, as he and his brother Lloyd outhit Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig 11–10 over the four games.

The brothers’ nicknames reportedly came from a Brooklyn fan, during an exceptionally productive day by the brothers at Ebbets Field. Reportedly, the fan’s comment was, “Them Waners! It’s always the little poison on thoid and the big poison on foist!”

An aggressive base runner, Waner was never afraid to take the extra base. He led the league in triples twice and doubles twice. His 62 doubles in 1932 is second best all-time in the National League.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .333, HR: 113, RBI: 1,309, H: 3,152, SB: 104

#95 Willie James “The Devil” Wells

SS-2B-3B, St. Louis Stars, Detroit Wolves, Homestead Grays, Kansas City Monarchs, Cole’s American Giants, Newark Eagles, Chicago American Giants, New York Black Yankees, Baltimore Elite Giants, Indianapolis Clowns, Memphis Red Sox, Birmingham Black Barons (Negro Leagues), 1924–49. Hall of Fame, 1997

Wells was the best shortstop in the Negro Leagues from the mid-1930s to the late 1940s. He was an excellent hitter and a very fundamentally sound infielder, who made up for a relatively weak throwing arm by studying hitters and trying to anticipate where they would hit the ball.

Wells rarely made acrobatic catches. Rather, he was usually right in front of the ball when it was hit. There are no fielding averages or records for assists or putouts for much of the history of the Negro Leagues. But Wells would likely be at the top or near the top of most of those lists.

Wells is credited with being one of the first professional players to wear a batting helmet. Because he often leaned over the plate while at bat, he was a frequent target of pitchers trying to “brush” him back.

One year, probably 1936, he was struck on the temple by a pitched ball. Advised by a doctor to refrain from playing for a time, Wells instead returned to the lineup the next day, wearing a modified construction helmet. He would wear it the rest of his career, and many other players began following suit.

Wells spent many years in the Mexican Leagues, where he was affectionately called “El Diablo” for his seemingly magical anticipation in the field.

Wells was happy to impart his wisdom to younger players, and throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was a player-manager in various minor leagues.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .328, HR: 138, H:1,306

#96 Albert William “Al” Kaline

OF-DH, Tigers, 1953–74. Hall of Fame, 1980

Kaline is also nicknamed “Mr. Tiger,” in part because he holds the team record for games played with 2,834 and home runs with 399, and in part because he represented Detroit so well for his entire 22-season career.

Kaline was, initially, a small, shy kid who worked for virtually everything he earned on a baseball field. He was signed right out of a Baltimore sandlot league in 1953 and didn’t play a game in the minors.

In 1954, Kaline’s first full season in the majors, it was clear that he would be a solid defensive outfielder: He had a good arm and excellent instincts. But he built up his wrists and arms, reportedly from exercises suggested by Boston’s Ted Williams, and by 1955, Kaline was a bona fide star. He won his only batting title that year, hitting .340, and stroked 200 hits, also tops in the league.

Kaline also smacked three home runs in one game at Kansas City that year, the only time in his career he would do so.

Kaline would hit .300 or better nine times in his career, and belt 20 or more home runs nine times.

He was one of the most graceful fielders of his era, and one of the best all time. Kaline earned 10 Gold Gloves in the outfield, and twice led the league in fielding percentage. In 1971, he played 133 games in the field without an error.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .297, HR: 399, RBI: 1,583, H: 3,007, SB: 137

#97 Juan Antonio “The Dominican Dandy” Marichal

RHP, Giants, Red Sox, Dodgers, 1960–75. Hall of Fame, 1983

Marichal was signed by the Giants in 1960, and was already a polished pitcher at age 19. Still, San Francisco brought the Dominican Republic native along slowly, as a sport starter. He went 6–2 with a solid 2.66 ERA.

In 1962, Marichal was a key performer in the Giants’ National League championship team with an 18–11 mark, although he injured his foot and lost his last three decisions. But from 1962 to 1969, Marichal won 172 games and lost 76. That comes out to an average 21–9 record.

He led the league in wins, innings pitched, shutouts and complete games twice in that span, and in ERA once. The sturdy Marichal three times threw more than 300 innings in a season, leading the league in that category twice.

Marichal’s high kick before his pitch was legendary, and also effective. It was distracting to hitters, and it made his fastball, slider and curve that much tougher to hit.

In August of 1965, in the heat of a tense pennant race with the Dodgers, Marichal got into a brawl with Dodger catcher John Roseboro, hitting Roseboro with his bat. A wild brawl ensued and when the smoke cleared, Roseboro was hospitalized with a concussion.

Roseboro subsequently sued Marichal for assault, but eventually dropped the suit.

Marichal retired in 1975, and after he was passed over for induction into the Hall of Fame, the classy Roseboro led a letter-writing campaign to install Marichal. It worked, and Marichal made it a point to thank Roseboro at his induction in 1983.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 243, L: 142, SV: 2, ERA: 2.89, SO: 2,303, CG: 244

#98 Frank Francis “Frankie,” “The Fordham Flash” Frisch

2B-3B-SS, Giants, Cardinals, 1919–37. Hall of Fame, 1947

The New York Giants signed Frisch straight out of Fordham University, where he was one of the greatest athletes in the history of the school, excelling in football, basketball, baseball and track. Frisch never played a day in the minors, although he was basically a utility infielder in his first season with the Giants.

By 1920, Frisch was a regular, hitting .280 with 34 stolen bases, 10 doubles and 10 triples.

But while his offensive numbers were always solid, Frisch never blew anyone away with his stats. His principal weapons were his prodigious speed, heady decision-making ability and coolness under pressure. Still, he hit .300 or better in 13 seasons and led the league in stolen bases three times. He was nearly impossible to strike out. Only twice in 19 years did Frisch whiff more than 20 times a season.

From 1921 to 1924, he helped the Giants to four consecutive National League pennants and two world championship. In four World Series with the Giants, Frisch hit .300 in 1921, .471 in 1922, .400 in 1923 and .333 in 1924, with 37 hits that included five doubles and three triples.

In 1927, Frisch was traded to the Cardinals, and his slashing, aggressive style helped Cardinal fans forget the departed Rogers Hornsby. And once again, Frisch was one of the keys in helping St. Louis to four National League crowns and another two wins in the World Series. He was MVP in 1931 and finished second in the voting in 1937.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .316, HR: 105, RBI: 1,244, H: 2,880, SB: 419

#99 Samuel Earl “Sam,” “Wahoo Sam” Crawford

OF-1B, Reds, Tigers, 1899–1917. Hall of Fame, 1957

Like many of his Tiger teammates, Crawford did not get along with Ty Cobb. But while Cobb and Crawford were never friends, Cobb had no choice but to respect the speedy, resilient, hard-hitting Crawford in the years they shared outfield duties.

Crawford began his career with the Reds, and jumped to the Tigers in 1903. Crawford, nicknamed after his hometown of Wahoo, Nebraska, was almost as intimidating on the base paths as Cobb. He didn’t spike opponents as often, but he always took the extra base.

He led the league in triples six times, and his lifetime total of 309 is still the best all-time. Crawford also led the league in doubles once and home runs twice. In fact, in 1901, he led the National League with 16 home runs and, in 1908, led the American League with seven. He became the only man to lead both leagues in homers.

Crawford and Cobb worked closely together. They frequently pulled a double steal, usually with Crawford going from first to second and Cobb going from third to home.

With Cobb batting ahead of him, Crawford led the league in RBI three times, and six times drove in 100 or more runs.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .309, HR: 97, RBI: 1,525, H: 2,961, SB: 366

#100 Mordecai Peter Centennial “Three-Finger,” “Miner” Brown

RHP, Cardinals, Cubs, St. Louis (FL), Brooklyn (FL), Chicago Whales (FL), 1903–16. Hall of Fame, 1949

Brown is the ultimate lemons-to-lemonade ballplayer. As a 7-year-old, he caught his right hand in his father’s corn grinder. That cost him his forefinger, which was amputated. His middle finger was permanently mangled. His little finger was cut to a stub.

But Brown learned to pitch by spinning the ball off his twisted middle finger, which, coupled with the velocity with which Brown threw, gave it a twisting, darting motion that was difficult for hitters to pick up.

Brown was signed by the Cardinals, but struggled to a 9–13 record. But Cub manager Frank Chance liked Brown’s toughness, and got him for Chicago in 1904. It was a fortuitous pickup. For six seasons, from 1906 to 1911, Brown won 20 or more games. His ERA from 1904 to 1908 was under 2.00 four of those five years. He also wasn’t afraid to pitch in relief between starts. He led the league in saves from 1908 to 1911. Brown was the ace of those dominant Cub teams, which won four pennants and two World Series in five years.

He was the Cubs’ “money pitcher.” Four of his five World Series wins were shutouts. His duels with Giant ace Christy Mathewson were electrifying. At one point, he owned Matty, beating him nine consecutive times.

The media, jumping on his handicap, called him “Three-Finger” Brown. His teammates called him “Miner,” as he had worked in the coal mines before he became a big leaguer.

Brown was probably the best pitcher in the short history of the Federal League, going 31–19 in two years, and helping the Chicago Whales to the 1914 Federal League pennant.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 239, L: 130, SV: 49, ERA: 2.06, SO: 1,375, CG: 271

#101 Carlton Fisk

C, Red Sox, White Sox, 1969, 1971–93. Hall of Fame, 2000

Fisk remains the best offensive catcher in baseball, with 1,276 runs scored, more than 100 more than any other backstopper, 3,999 total bases, far ahead of any other catcher, and more stolen bases (128) than Johnny Bench, Yogi Berra and Mike Piazza combined.

The first player to be voted Rookie of the Year unanimously, Fisk was a tremendous weapon for the Red Sox in the 1970s, hitting .290 or better five times and getting 100 or more hits six times. And how many catchers ever led the league in triples, as Fisk did in 1972, with nine? Fisk has more career triples (47) than Bench, Piazza and Roy Campanella combined. In 1972, he won a Gold Glove for his catching and led the AL in triples (9).

Fisk was injured for part of the 1975 season, but rebounded to hit .331 and lead Boston into the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. He was the center of two of the key plays in the Series. The first came in the 10th inning of Game Three, when he collided with Ed Armbrister while trying to field a bunt. No interference was called on Armbrister, even though it was clear Fisk’s ability to field the ball was impeded. The Sox lost that contest.

But in Game Six, he hit the most dramatic home run in Series history. He blasted a pitch by Red hurler Pat Darcy into the night in the 12th inning, and there probably aren’t too many people who haven’t seen Fisk jumping into the air, hands upraised, as the ball leaves Fenway Park.

He wasn’t as effective with the White Sox. But no matter where he was, Fisk was a clubhouse leader and a masterful handler of pitchers.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .269, HR: 376, RBI: 1,330, H: 2,356, SB: 128

#102 William “Judy” Johnson

3B, Hilldale Daisies, Homestead Greys, Darby Daises, Pittsburgh Crawfords (Negro Leagues), 1918–38. Hall of Fame, 1988

A solid, unspectacular, but fundamentally sound third baseman who toiled in the Negro Leagues for 20 years, Johnson joined the famous Philadelphia Hilldales in 1921 and was the anchor of the infield for eight years. He hit .364 in the 1924 black World Series in a losing cause.

Johnson was a “scientific hitter,” which meant he didn’t hit for much power. He was perennially a .300-plus hitter throughout his years in the Negro Leagues, however, and was renowned for his clutch hitting. In 1930, he joined the Pittsburgh Crawfords as a player-manager, making him a part of perhaps the greatest dynasty in Negro League history. The 1935 Crawfords are considered the greatest Negro League team of all time.

Following his retirement in 1938, Johnson worked as a scout for several major league teams.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, H: 1,100

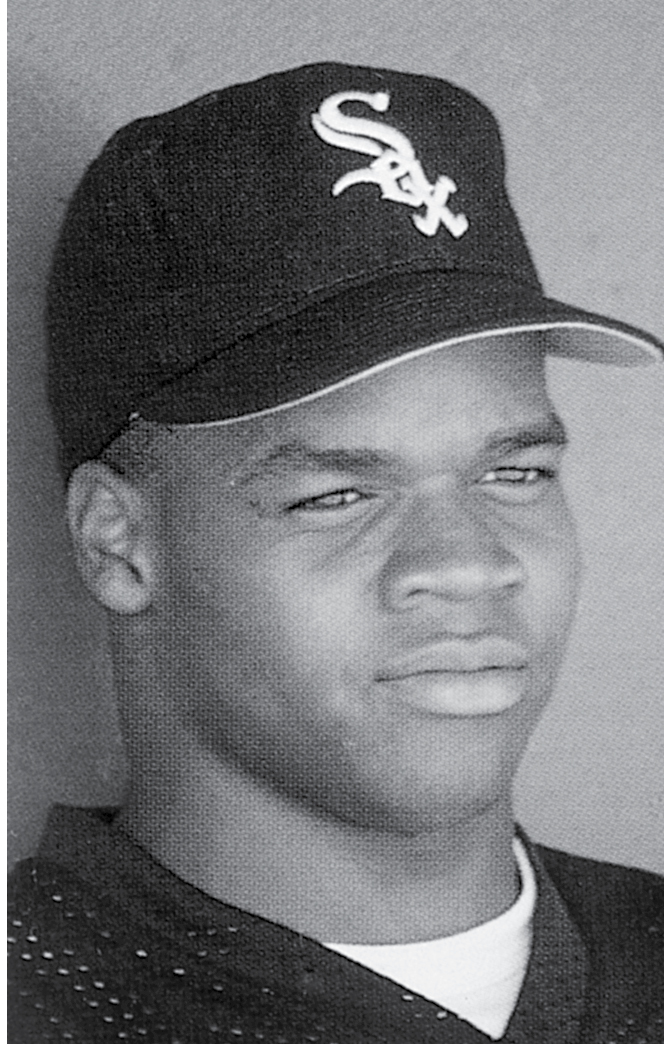

#103 Frank “The Big Hurt” Thomas

1B-DH, White Sox, A’s, Blue Jays, 1991–2007. Hall of Fame, 2014

Here’s a guy who, for the first eight years of his career, was on fire. From 1990 to 1997, “The Big Hurt” was a five-time All Star, and he was the American League MVP in 1993 and 1994. His numbers in the years before and after those seasons were not appreciably different.

In fact, in that 1990 to 1997 span, he hit .300 or better every year, had 109 or more walks every year, and was consistently among the league leaders in on-base and slugging percentages.

Since 2000, plagued by injuries, Thomas’ numbers began to dip, although he bounced back after going to the Oakland A’s in 2005, hitting .270, with 39 homers.

His best postseason year was 1993, when he hit .393 for the Sox in the American League Championship Series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .303, HR: 501, RBI: 1,622, H: 2,332, SB: 32

#104 William Frederick Bill “Bad Bill” Dahlen

SS, White Stockings, Dodgers, Giants, Braves, 1891–1911

Nicknamed “Bad Bill” because of his altercations with umpires, Dahlen was a good-hitting, sure-handed shortstop for National League teams for a record 20 years. He broke in with Chicago, and played third base, outfield and second base as well as shortstop his first few years there. Player-manager Adrian “Cap” Anson was asked why he kept moving Dahlen around so much. Cap replied that he didn’t really give a damn where Dahlen played, as long as he was in the lineup.

In nine years with Chicago, Dahlen his .290 or better six times. He was an excellent runner, as well. Dahlen stole 60 bases in 1892 and 51 in 1896. He is still in the top 30 in stolen bases all-time. He was also a superb fielder, and is still second all-time in putouts for a second baseman with 4,850 and third in assists with 7,500.

Dahlen had a 42-game hitting streak in 1894, which was a record for two years, until Wee Willie Keeler broke it. After going hitless in Game 43, Dahlen embarked on a 28-game streak, meaning he hit safely in 70 of 71 games.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .272, HR: 84, RBI: 1,233, H: 2,457, SB: 547

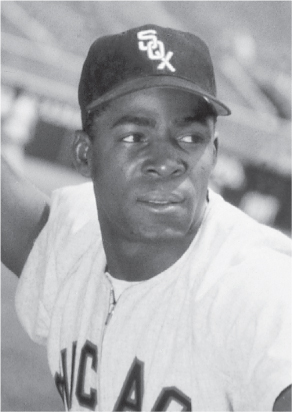

#105 Saturnino Orestes Arrieta “Minnie,” “The Cuban Comet” Minoso

OF, Cleveland, White Sox, Cardinals, Senators, 1949–1964, 1976, 1980

In his first game with the White Sox in 1951, Minnie Minoso became the first black player to don a Chicago uniform in the history of the team. In the first inning of the game, he homered off Yankee pitcher Vic Raschi.

Minoso was a three-time Gold Glove winner who had consistently good numbers throughout his career. He led the league in stolen bases three times: in 1951, 1952 and 1953. In 1954, he led the league in triples, with 18, and a .535 slugging percentage. In 1957, Minoso led the league in doubles with 36. He also had no problems leaning into a pitch: He was hit by pitchers 192 times in his career, a league record.

Minoso is one of only two players (along with Nick Altrock) to have played in five decades. The record is something of a gimmick; he was activated for three games in 1976 (he went 1–8) and two more in 1980 (0–2).

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .298, HR: 186, RBI: 1,023, H: 1,963, SB: 205

#106 Barry Louis Larkin

SS, Cincinnati, 1986–2004. Hall of Fame, 2012

Larkin was one of the best all-around players in the 1990s, and, at 39, continues to play at a high level into the 21st century.

You want hitting? Between 1988 and 2000, 11-time All Star Larkin hit better than .300 nine times. Three other years, he hit .293 or better. You want baserunning? Larkin stole 40 bases in 1988 and 51 in 1995. His lifetime success ratio is 83 percent.

He is an excellent fielder, leading the league in 1994 with a .980 average, and only once dropping below .975. Larkin is a three-time Gold Glove winner. He was the league MVP in 1995, the year the Reds won the World Series. In 1996, he became the first shortstop ever to hit more than 30 home runs and steal 30 bases in the same season.

In the 1996 All Star game, Ozzie Smith, the best shortstop in the league, presented Larkin with an autographed bat and told him, “The torch is now officially passed.”

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 198, RBI: 960, H: 2,340, SB: 379

#107 Jeffrey Robert “Jeff” Bagwell

1B, Astros, 1991–2005

Pittsburgh won the National League crown. The Pirates were creamed by the Yankees that year in four games, but Paul hit .333, as he and his brother Lloyd outhit Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig 11–10 over the four games.

The brothers’ nicknames reportedly came from a Brooklyn fan, during an exceptionally productive day by the brothers at Ebbets Field. Reportedly, the fan’s comment was, “Them Waners! It’s always the little poison on thoid and the big poison on foist!”

An aggressive base runner, Waner was never afraid to take the extra base. He led the league in triples twice and doubles twice. His 62 doubles in 1932 is second best all-time in the National League.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .297, HR: 449, RBI: 1,529, H: 2,314, SB: 202

#108 Paul Leo “The Igniter,” “Molly” Molitor

DH-3B-2B-1B-SS-OF, Brewers, Blue Jays, Twins, 1978–98. Hall of Fame, 2004

Molitor was one of the most versatile players in the majors during his first decade as a player. For the first three years of his career with the Brewers, Molitor was the team’s starting second baseman, and also played shortstop and third base. He was switched to third base in 1982, and played there, for the most part, over the next seven years, but also played shortstop, second base and the outfield.

Molitor was moved to the designated hitter slot more or less permanently in 1991, but was also used at first base for as many as 40 games a season. This was less because of any defensive liability, and more to protect Molitor from injury.

At the plate, he was Mr. Consistency. He hit .300 or better 12 times, scored 90 or more runs eight times, topped 190 hits six times and five times scored 100 runs or more. A total of 13 times in his career, Molitor stole 20 or more bases. In 1987, Molitor had a 39-game hitting streak.

Molitor is 10th lifetime in doubles with 605, ninth lifetime in hits with 3,319, 11th lifetime in sacrifice flies with 109 and 17th lifetime in runs scored with 1,782.

Molitor has been outstanding in the postseason. He has hit .368 in five series, including .418 in two World Series. In 1993, in the Blue Jays’ win over the Phillies, Molitor was 12 for 24 with two home runs, two doubles and 10 runs scored to win the MVP award.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .306, HR: 234, RBI: 1,307, H: 3,319, SB: 504