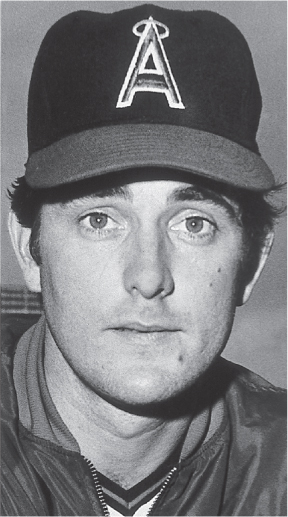

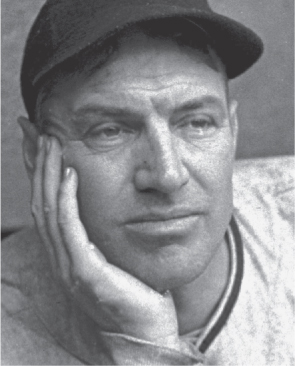

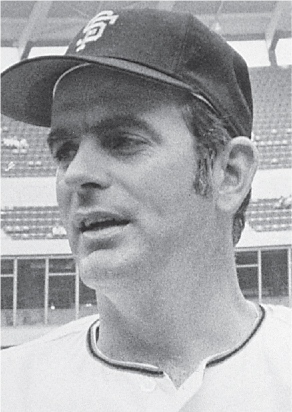

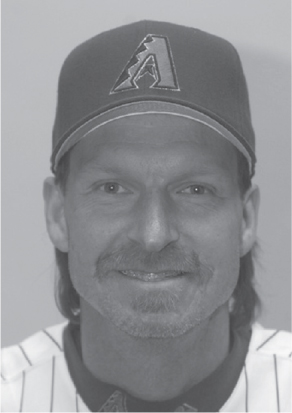

#109 Lynn Nolan “The Ryan Express” Ryan

RHP, Mets, Angels, Astros, Rangers, 1966–93. Hall of Fame, 1999

The strikeout king, with 5,714. Nobody else is even close. A model of consistency and durability, Nolan Ryan pitched for 27 years in the big leagues, finally retiring at age 46.

Somehow, people have the impression that Ryan’s numbers are misleading. Until late in his career, when he punched out a league-leading 301 batters at age 42 in 1989, the “book” on Ryan was that he wasn’t a winner. (He was a World Series winner: the 1969 Mets.) Certainly many of his teams weren’t successful, but Ryan, an eight-time All Star, won 324 games in his career. He struck out 300 or more batters in six separate seasons and has thrown a major league record seven no-hitters. He broke Sandy Koufax’s single-season record of 382 strikeouts, getting 383 in 1973.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 324, L: 292, SV: 3, ERA: 3.19, SO: 5,714, CG: 222

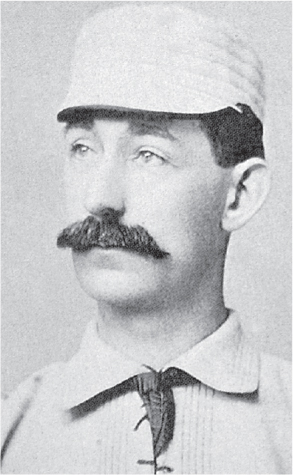

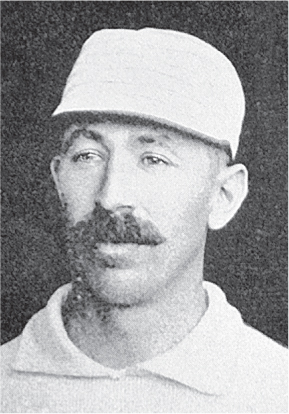

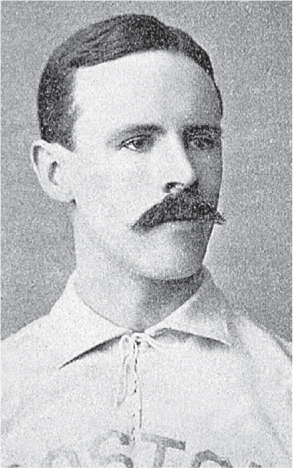

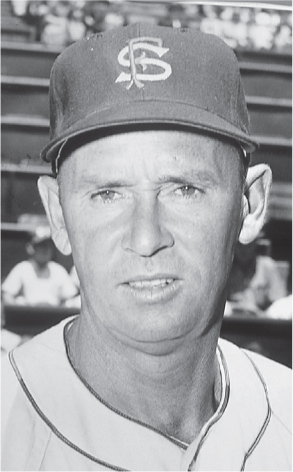

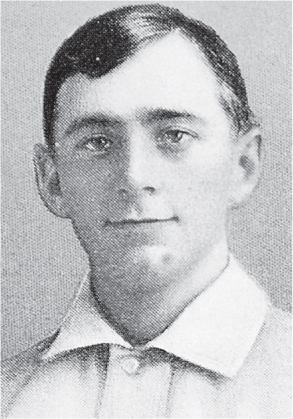

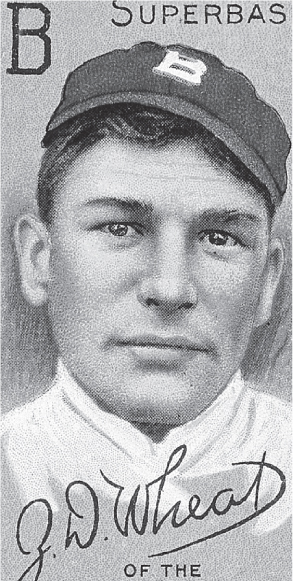

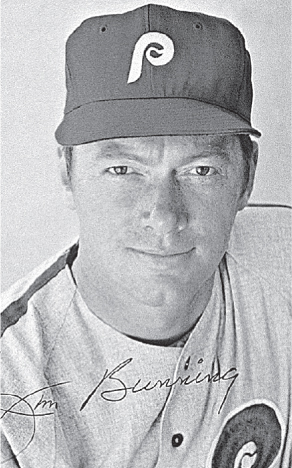

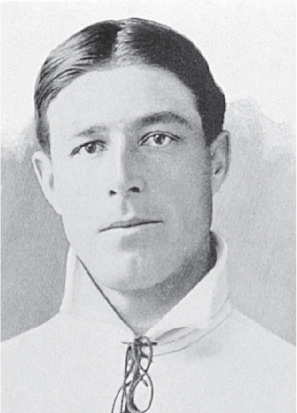

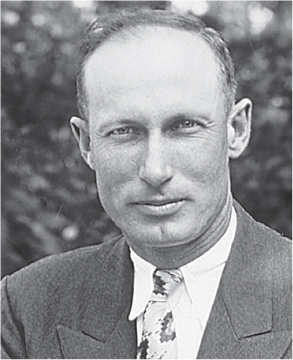

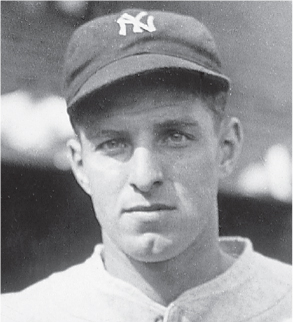

#110 Timothy John “Smiling Tim,” “Sir Timothy” Keefe

RHP, Troy (NL), New York (AA), Giants, New York (PL), Phillies, 1880–93. Hall of Fame, 1964

Keefe was one of the best pitchers of the 1880s, twice winning 40 or more games in a season and winning 30 or more four times.

This was the era of mounds that were only 50 feet from home plate, and Keefe’s fastball was a devastating weapon. He struck out 300 or more batters three times in his career, leading the league in 1883 and 1888. He lead his league in ERA three times, including a minuscule .086 his rookie season.

The 1883 season was Keefe’s best. Keefe struck out a league-leading 359 batters, worked 619 innings, and started 68 and completed 68 games, all league bests. His ERA was 2.41.

That year, he won both ends of a doubleheader against Columbus, throwing a one-hitter in the morning game and a two-hitter in the afternoon.

In 1888, pitching for the Giants, Keefe won 35 games, had eight shutouts, 335 strikeouts and a 1.74 ERA, all league bests. He won four more contests in a postseason championship series against American Association champion St. Louis. Keefe had 30 strikeouts and allowed only two earned runs, as the Giants won the series.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 342, L: 225, SV: 2, ERA: 2.62, SO: 2,562, CG: 554

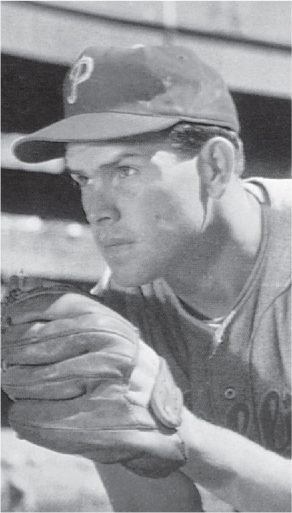

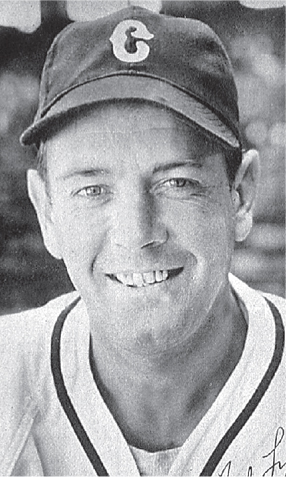

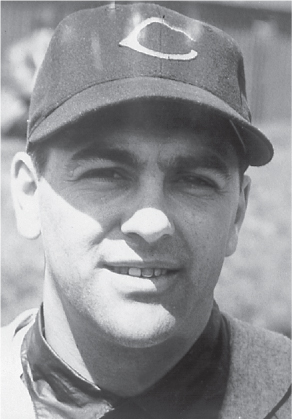

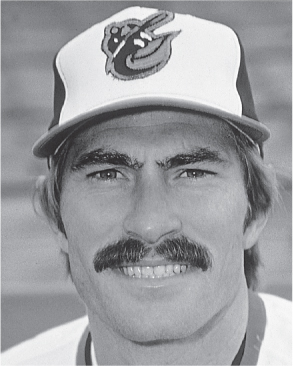

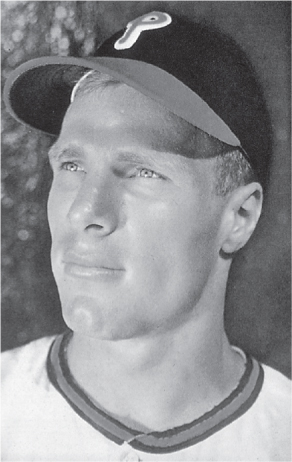

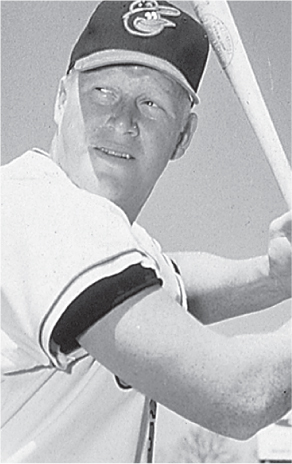

#111 Robin Evan Roberts

RHP, Phillies, Orioles, Astros, Cubs, 1948–66. Hall of Fame, 1976

Robin Roberts in 10 words or less: “Hated to come out; let ‘em hit the ball.”

The seven-time All Star remains the winningest right-hander in the history of the Philaelphia Phillies. He won 20 games or more six years in a row, from 1950 to 1955 and from 1952 to 1955, led the league in wins. He also led the league in complete games from 1952 to 1956 and pitched 300 or more innings for six seasons in a row, from 1950 to 1955.

A lanky righty with a smooth motion, Roberts also gave up a lot of home run balls, although it often seemed that most of them occurred with the bases empty. Still, he gave up a major-league record 46 dingers in 1956. Roberts wasn’t quite as dominant after the early to mid-1950s, and struggled with arm trouble for a while. But he bounced back in 1962 to 1964, winning 37 games for Baltimore.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 286, L: 245, SV; 25, ERA: 3.41, SO: 2,357, CG:305

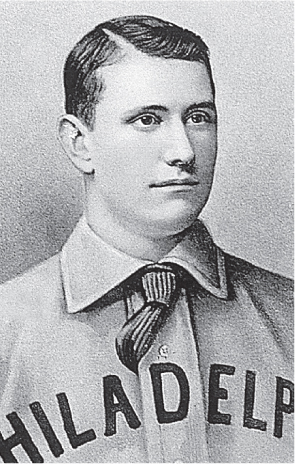

#112 Edward James “Big Ed” Delahanty

OF-1B, Phillies, Cleveland (PL), Senators, 1888–1903. Hall of Fame, 1945

One of a long string of 19th-century baseball players who fought a losing battle with the bottle, the most enduring story about Delahanty is that, in June of 1903, he was put off a train at International Bridge, near Niagara Falls, for being drunk and disorderly. Unfortunately, Big Ed, unable to see in the dark, began walking the tracks and fell through an open drawbridge into Niagara Falls, which killed him.

Delahanty was a fearsome slugger, who hit .400 or better three times in his career and led the league in doubles five times, triples once and home runs twice. In 1896, he just missed the Triple Crown, with 13 home runs, 126 RBI and a .397 batting average, which was third in the league, behind Jesse Burkett’s .410 and Hughie Jennings’ .401. He was also pretty fleet afoot, stealing 30 or more bases six times in his career. In 1898, he stole a league-leading 58 bases.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .346, HR: 101, RBI: 1,464, H: 2,596, SB: 455

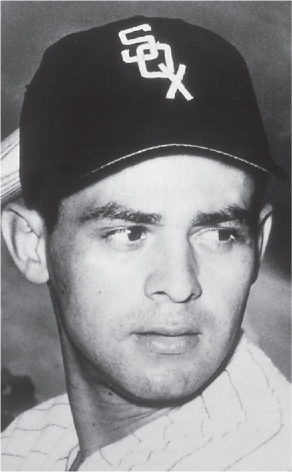

#113 Lucius Benjamin “Luke,” “Old Aches and Pains” Appling

SS, White Sox, 1930–50. Hall of Fame, 1964

Despite his one-of-a-kind nickname, Appling held down the shortstop’s job for the Chicago White Sox for 20 years, and usually played most of his team’s games at that position every year.

Appling was a sweet-hitting, good-fielding shortstop for most of his career. The eight-time All Star won two batting championships, in 1936 with a .388 average and in 1943, when he hit .328. He hit .300 or better 16 times and his lifetime average is .310.

He was one of the most frustrating leadoff batters in baseball history. With his sharp batting eye, Appling would patiently foul off ball after ball until he got a good pitch to hit. He once reportedly fouled off 17 pitches in one at bat before hitting a triple. Appling was voted the Greatest White Sox Player Ever in 1969.

Appling’s batting title in 1936 was the first ever such title for a White Sox player.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .310, HR: 45, RBI: 1,116, H: 2,749, SB: 179

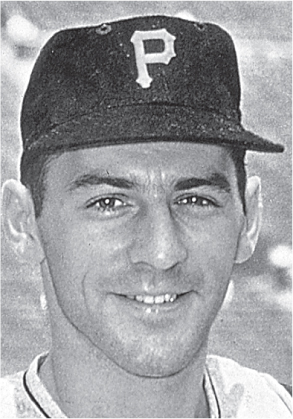

#114 Harold Joseph “Pie” Traynor

3B-SS, Pirates, 1920–36. Hall of Fame, 1948

There was a point in the 1950s and 1960s when Pie Traynor was dubbed the greatest third baseman in baseball history. Mike Schmidt, George Brett, Ron Santo and Eddie Mathews have since disabused that claim, but Traynor remains one of the all-time greats.

An excellent fielder of bunts and slow rollers down the line, Traynor also batted .300 or better 10 times. A two-time All Star, Traynor almost never struck out, ending up with only 278 career whiffs, or about 16 a season.

Traynor did not have a lot of power in cavernous Forbes Field, but he hit 20 or more doubles in 11 consecutive seasons and 10 or more triples 11 times in his career.

Traynor’s nickname has a number of possible origins, but the most common one is that he was said to have been fond of pies as a youth in Framingham, Massachusetts.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .320, HR: 58, RBI: 1,273, H: 2,416, SB: 158

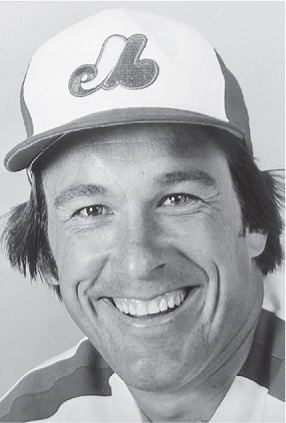

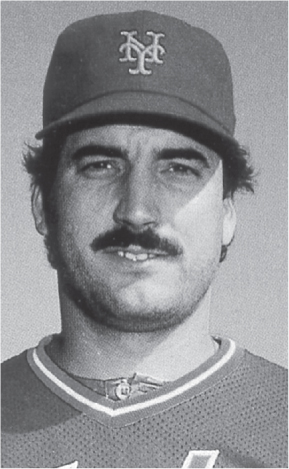

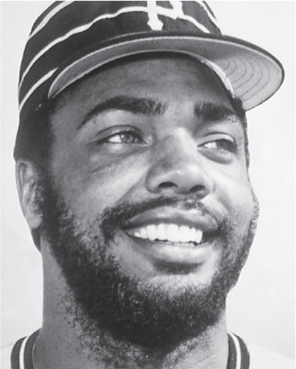

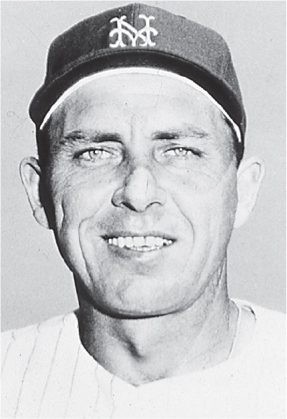

#115 Gary Edmund “The Kid” Carter

C, Expos, Mets, Giants, Dodgers, 1974–92. Hall of Fame, 2003

The ebullient Carter was one of the most popular players in the 1970s and 1980s, and one of the best catchers in that span, as well.

The 11-time All Star was the anchor of the Montreal Expos in the 1970s and early 1980s. Between 1977 and 1982, Carter led National League catchers in most chances six times, putouts six times, assists five times and double plays four times.

He was traded to the Mets in 1984, and led New York to the 1986 World Championship. His single in the 10th inning of Game Six of that World Series was one of the key blows in that amazing three-run rally.

Carter won three Gold Gloves during his career, but many believe his fielding was vastly underrated, probably because he was such a good hitter. Carter was also well known for being a good handler of younger pitchers.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .262, HR: 324, RBI: 1,225, H: 2,092, SB: 39

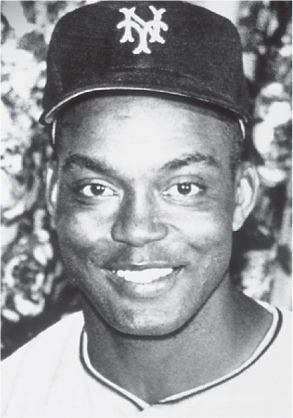

#116 Billy Leo Williams

OF-DH-1B, Cubs, Athletics, 1959–76. Hall of Fame, 1987

Billy Williams was the quiet assassin for the Chicago Cubs for 17 years. Often overshadowed by teammate Ernie Banks, Williams was nonetheless one of the most durable players in National League history, playing in a record 1,117 consecutive games, a National League mark later broken by Steve Garvey in 1983.

Williams had a lovely swing that Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby recognized immediately. At Williams’ first tryout with the Cubs, Hornsby deemed the soft-spoken Williams as major league material immediately.

The six-time All Star won a batting crown in 1972, at age 34. He hit 20 or more home runs 13 years in a row and 14 out of 15 seasons.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .290, HR: 426, RBI: 1,475, H: 2,711, SB: 90

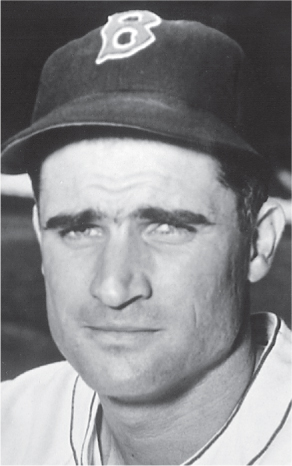

#117 Robert Pershing “Bobby” Doerr

2B, Red Sox, 1937–43, 1946–51. Hall of Fame, 1986

Bobby Doerr was the gem of the Red Sox infield in the 1940s: a steady hitter and sure-handed fielder who simply never seemed to make a mistake at the plate or in the field.

Doerr was a veteran when he was signed by the Red Sox in 1937 as a 19-year-old rookie; by then, he had been playing pro ball for three years in the Pacific Coast League. When he came to Boston, he was a Sea of Tranquility in the roiling Red Sox clubhouse.

Doerr led league second basemen in fielding percentage four times during his career, but he was also a steady hitter, topping .300 three times, driving in more than 100 runs six times and leading the league in slugging (.528) in 1944. Like many of his contemporaries, he lost two years to World War II, but in 1946, came back to lead Boston to its first pennant since 1918. Doerr hit .409 in the 1946 World Series against the Cardinals.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .288, HR: 223, RBI: 1,247, H: 2,042, SB: 54

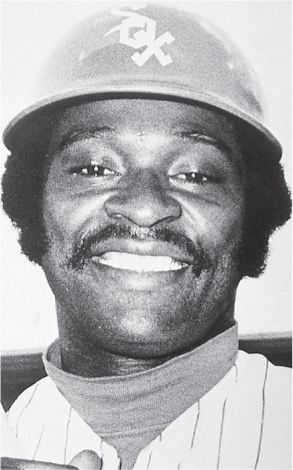

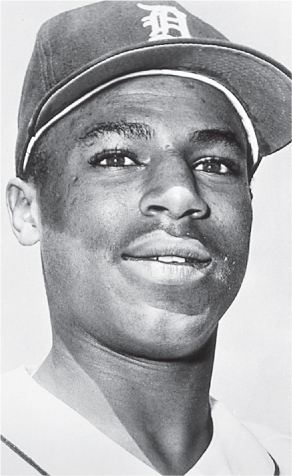

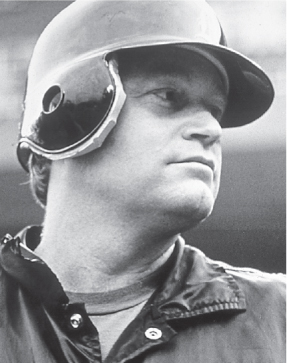

#118 Richard Anthony “Dick” Allen

1B-3B, Phillies, Dodgers, Cardinals, White Sox, Athletics, 1963–77

Dick Allen was one of the greatest athletes in the history of the game. He was also, hands down, one of its greatest enigmas.

Immensely talented, often incredibly, amazingly contradictory, Allen generated as much newsprint for his eccentric behavior as for his ball-playing abilities.

He was a seven-time All Star. He hit better than .300 seven times, socked 20 or more home runs 10 times, and was the American League MVP in 1972. But in 1974, he was on his way to another big year when he “retired” for no good reason—or at least for no reason he would tell anyone about.

Allen feuded with coaches and with fans. Interestingly, he got along, for the most part, with his teammates, who knew enough to let him alone. It adds up to a very good career, but one that probably could have been much better.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .292, HR: 351, RBI: 1,119, H: 1,848, SB: 133

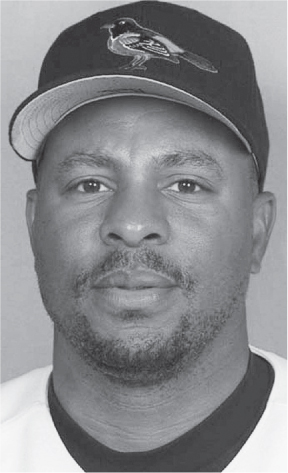

#119 Raymond Emmitt “Ray” Dandridge

3B-2B-SS, Detroit Stars, Nashville Elite Giants, Newark Dodgers, Newark Eagles, New York Cubans (Negro Leagues), 1933–49. Hall of Fame, 1987

The good-hitting, smooth-fielding Dandridge was the greatest third baseman in the history of the Negro Leagues.

Accounts of Dandridge’s prowess emphasize his smooth fielding and rocket arm from the hot corner. But he was also an excellent hitter, compiling a lifetime .355 in the Negro National League. He was even better in All Star games, hitting .545 in three such contests.

Dandridge was clearly one of the best players, black, white or otherwise, of the 1940s. In fact, he was probably better than Jackie Robinson, the man chosen by the Dodgers to break the color barrier.

But Dandridge never made it to the big leagues. He was signed by the New York Giants in 1949 and assigned to their AAA team. He won the MVP award in 1950 and led the Giants’ Minneapolis farm team to the league championship. It wasn’t enough at the time.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .350, H: 408

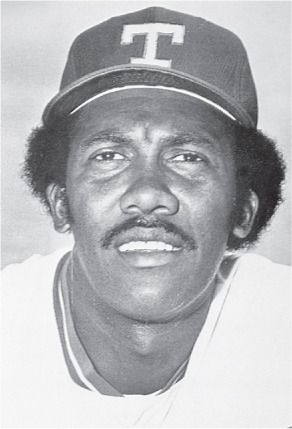

#120 Ferguson Arthur “Fergie” Jenkins

RHP, Phillies, Cubs, Rangers, Red Sox, 1965–83. Hall of Fame, 1991

As a pitcher, Jenkins was durable, athletic and consistent. Yet during his playing years, he rarely got the credit he deserved.

Jenkins won 20 games or more six years in a row and seven years out of eight between 1967 and 1974. From 1967 to 1972, he won 127 games for the Cubs. In that span, Chicago had seven 20-game winners: Jenkins (six times) and Bill Hands. In other words, it was Ferguson Jenkins and a cast of dozens. Five times, he pitched more than 300 innings in a season.

Yet Jenkins was named to only three All Star teams. He won the Cy Young Award in 1971, but he won more games in 1974, struck out more men in 1969 and 1970 and held opponents to lower batting averages in 1968, 1969 and 1970.

Jenkins won 284 games in his career and struck out 3,192.

In 1991, Jenkins became the first Canadian-born player to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 284, L: 226, SV: 7, ERA: 3.34, SO: 3,192, CG: 267

#121 William “Buck” Ewing

C-1B, Troy Trojans, Giants, Cleveland Spiders, Reds, 1880–97. Hall of Fame, 1939

Buck Ewing was clearly the greatest catcher of the 19th century, a solid hitter and terrific receiver.

Ewing was a great hitter, averaging .300 or better in 11 of his 18 years. He was a daring base runner, with more than 354 steals from 1886–97. Prior to that, statistics on steals were not kept. And he was an outstanding defensive catcher. Ewing pioneered the practice of throwing base runners out from a crouch. No one had ever seen catchers do that before.

Actually, Ewing was a great all-around player who could have played anywhere and sometimes did. In 1882, playing for Troy, he played all four infield positions, pitched, caught and played the outfield in various games during the year.

He was fast enough to be the leadoff hitter for many years for Troy and the Giants, and was also a home run threat in the “dead ball” era, leading the league in dingers in 1883.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .303, HR: 71, RBI: 883, H: 1,625, SB: 354

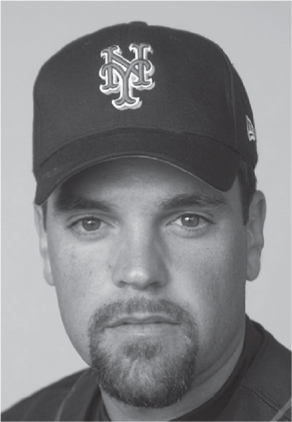

#122 Michael Joseph “Mike” Piazza

C-DH-1B, Dodgers, Mets, Marlins, Padres, A’s, 1992–2007. Hall of Fame, 2016

In 2004, Piazza became the all-time leader in home runs by a catcher. On May 5, 2004, he blasted his 352nd dinger, leaving him one ahead of Carleton Fisk. A superior athlete, Piazza has hit 30 or more home runs nine times in his career, and has hit 40 homers twice.

Piazza was drafted by the Dodgers, and brought up at the tail end of 1992. He played his first full season in 1993, and was named Rookie of the Year, on the basis of a .318 batting average, 35 home runs, 112 RBI, 24 doubles and 174 hits.

Piazza is a great all-around hitter. In addition to socking home runs, he has hit .300 or better nine consecutive seasons, from 1993 to 2001. A 10-time All Star, Piazza’s .319 career batting average is fourth among active players and 55th all-time.

In 1996, he won the league MVP award, hitting .336 with 36 home runs, 105 RBI, 184 hits and 87 runs scored.

He was traded to the Mets in 1998, and, in 2000, was a key to New York’s National League championship. Piazza batted .324 with 38 home runs, 113 RBI and 90 runs scored that season.

Piazza, when healthy, was amazingly consistent. He generally hit between 35 and 40 homers a year, scored 80 to 100 runs, made 150 to 200 hits and drove in 90 to 120 runs. He was generally a tough out in the post-season, and hit four home runs and five doubles in 10 games in the National League Championship Series win over the Cardinals and the World Series loss to the Yankees in 2000.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .309, HR: 420, RBI: 1,299, H: 2,071, SB: 17

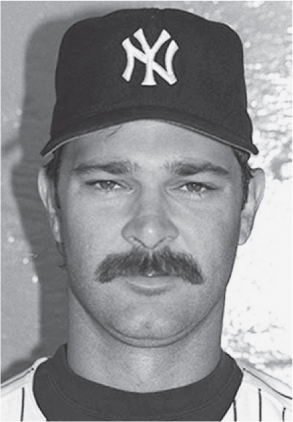

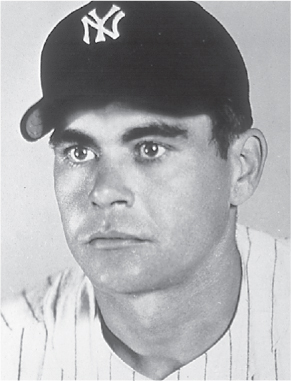

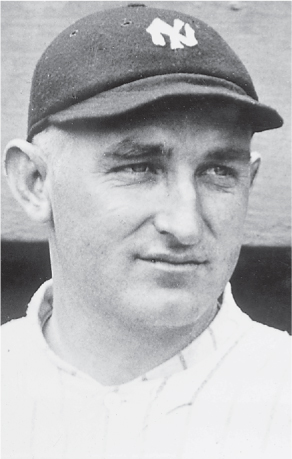

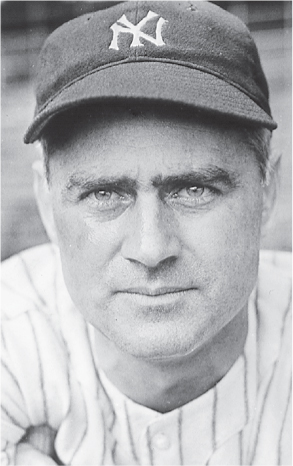

#123 Donald Arthur “Don,” “Donnie Baseball” Mattingly

1B, Yankees, 1982–95

Unlike many superstars who play a year or two (or three) beyond their time, Mattingly is the one guy who should not have retired when he did.

Donnie Baseball was playing pretty well at the end of the 1995 season, but he felt he could not perform up to the standards that he had set, and left baseball. The next season, the Yankees won their first World Championship in 18 years. There is not a Yankee fan alive who doesn’t wish the classy Mattingly had hung around.

He was great. He won nine Gold Gloves, a record for first basemen. He was a six-time All Star. He was MVP of the league in 1985 and probably should have won it again in 1986 (Boston’s Roger Clemens beat him out).

But by 1992, his back was bothering him and it began to get tough to play. Still, he hung in there for three more years, and always played hard. In his only postseason series, a loss to the Seattle Mariners, Mattingly acquitted himself well, hitting .417 with six RBI.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .307, HR: 222, RBI: 1,099, H: 2,153, SB: 14

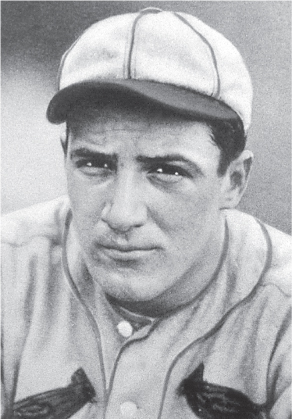

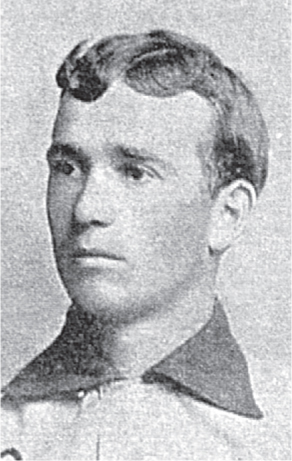

#124 Amos Wilson “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” Rusie

RHP, Indianapolis, Giants, Reds, 1889–1901. Hall of Fame, 1977

Amos Rusie is the original power pitcher and one of the principal reasons the mound had to be moved back from 50 feet to 60 feet, six inches, in 1893.

At 6'1", 200 pounds, Rusie was a scary guy. He had a good curve ball and a nice change of pace, but most of the time, he just reared back and fired the ball in.

His first few years in the league, Rusie was a terror. He struck out 341, 337 and 304 batters from 1890 to 1892. But in that same span, he also walked 289, 262 and 267 batters. He was all over the place. When the mound was moved back prior to the 1893 season, Rusie, like every other pitcher, threw fewer games and had fewer strikeouts and walks, but he was still very effective.

Rusie won 30 or more games five years in a row and 20 or more eight years in a row. But like many 19th-century pitchers, all that work burned up his arm. He retired in 1901.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 245, L: 174, SV: 5, ERA: 3.07, SO: 1,950 CG: 393

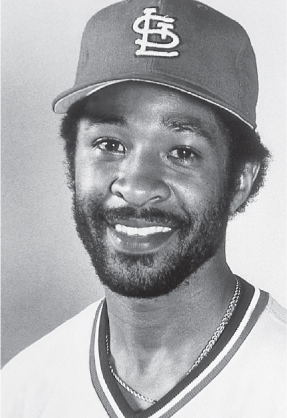

#125 Osborne Earl “Ozzie,” “The Wizard of Oz” Smith

SS, Padres, Cardinals, 1978–96. Hall of Fame, 2001

It’s almost impossible, on a statistical basis, to judge which individual might have been the greatest defensive player at his position. Fielding averages don’t measure range, or arm accuracy. But it’s very hard to dismiss Smith as at least the best defensive shortstop ever.

He was a 15-time All Star and a 13-time Gold Glove winner. Smith was not an overpowering hitter. But he made 100 hits or more 17 consecutive years and stole 580 bases for his career. His postseason numbers are good, but not great, except for 1982, when he hit .556 in the National League Championship Series against the Braves.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .262, HR: 28, RBI: 793, H: 2,460, SB: 580

#126 Wilbur “Bullet,” “Bullet Joe” Rogan

RHP, Kansas City Colored Giants, Kansas City Monarchs (Negro Leagues), 1917–38. Hall of Fame, 1998

Bullet Joe Rogan got his nickname not so much for his fireballing delivery, but for his pinpoint accuracy on the mound.

Rogan was an outstanding pitcher for the Kansas City Monarchs, boasting a variety of pitches and deliveries. He threw sidearm, and could throw a fastball, curve, forkball, palmball and spitball for strikes.

But Rogan was also an exceptional hitter. In 1922, he hit 13 home runs in 47 league games for the Monarchs. In 1924, he hit .411 and led the Negro American League in victories with 16.

Rogan started out as a catcher, but began his pitching career with the 25th Infantry Wreckers Army team in 1911.

Rogan’s career winning percentage of .699 is the best ever in the Negro American League.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 151, L: 65

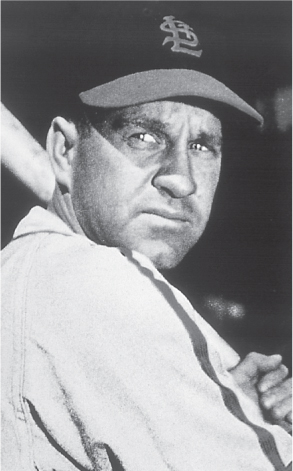

#127 Joseph Michael “Ducky-Wucky,” “Muscles” Medwick

OF, Cardinals, Dodgers, Giants, Braves, 1932–48. Hall of Fame, 1968

Joe Medwick is known for two things: winning the last Triple Crown in the National League in 1937 and inciting a near-brawl in 1934.

The Triple Crown (.374 batting average, 31 homers, 154 RBI) also got Medwick the MVP Award that year. It was one of those years where everything dropped in for Ducky-Wucky: he also led the league in runs scored (111), hits (237), doubles (56), slugging percentage (.641) and even fielding percentage for an outfielder (.988).

The brawl was not really his fault. The Cardinals were pounding Detroit 9–0 in Game Seven of the World Series. Medwick tripled and slid hard into third baseman Marv Owen, even though the throw hadn’t come in yet. This incensed the already annoyed Tiger fans, and when Medwick took the field in the bottom of the inning, he was pelted with bottles and garbage.

Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, who was in attendance, and fearing for Medwick’s safety, ordered him into the dugout so the game could resume. One has to wonder what would have happened if Medwick had refused.

Medwick picked up his nickname in the minor leagues because of his unusual, duck-like gait.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .324, HR: 205, RBI: 1,383, H: 2,471, SB: 42

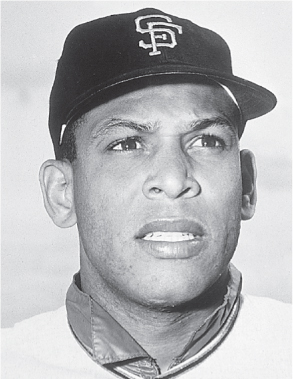

#128 Orlando “The Baby Bull,” “Cha Cha” Cepeda

1B-OF, Giants, Cardinals, Braves, Athletics, Red Sox, Royals, 1958–74

Cepeda was one of the greatest pure hitters in the history of the league. In his first big-league game, he socked a game-winning home run. A seven-time All Star, Cepeda topped .300 nine times in his career and topped .295 one other seasons.

A knee injury in 1965 slowed Cepeda down in the field, but he was still a tremendous hitter. In 1973, he was traded to the Red Sox, where he became a designated hitter, hitting .289 with 20 homers and 25 doubles. Sox pitcher Bill Lee, in his autobiography, recalled that a nearly immobile Cepeda would drill pitches to all corners of Fenway Park that year.

Cepeda’s father, Orlando Sr., was a star in the Cuban Leagues. His nickname was “The Bull.” Thus, his son became “The Baby Bull.”

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .297, HR: 379, RBI: 1,365, H: 2,351, SB: 142

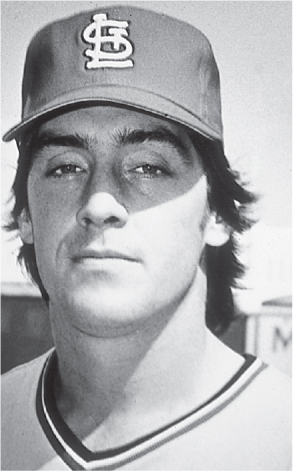

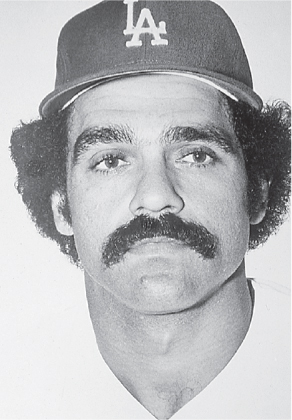

#129 Carl Reginald “Reggie” Smith

OF-1B, Red Sox, Cardinals, Dodgers, Giants, 1966–82

An outstanding athlete, Reggie Smith had a tremendous career that was often overshadowed by more illustrious teammates. In Boston, he was a two-time All Star performing in the shadow of Carl Yastrzemski. He was traded to the Cardinals and was a two-time All Star there, also, but all anyone talked about in St. Louis was Lou Brock and Al Hrabosky. With the Dodgers it was Steve Garvey and Dusty Baker.

Still, the switch-hitting Smith went about his business, hitting .300 or better five times and 20 or more homers seven times. He hit 314 home runs; second only to Mickey Mantle as a switch-hitting power hitter. He remains the only switch-hitter to hit 100 or more round-trippers in both the American and National Leagues and the only player to hit a home run from each side of the plate at least twice in both leagues.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .287, HR: 314, RBI: 1,092, H: 2,020, SB: 137

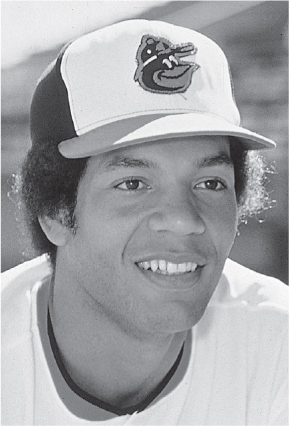

#130 Luis Ernesto “Little Louie” Aparicio

SS, White Sox, Orioles, Red Sox, 1956–73. Hall of Fame, 1984

Luis Aparicio began playing professionally when he was just a teen, in his native Venezuela. His personal coach was perhaps the greatest shortstop in the history of the Venezuelan Leagues, Luis Aparicio Sr.

Luis Jr. was signed by the White Sox, who were so confident he would make it, they traded the incumbent, Chico Carrasquel. Chicago’s confidence was not misplaced. Aparicio became a nine-time Gold Glove winner at shortstop and led the American League in stolen bases for nine consecutive seasons, from 1956–64.

He teamed with second baseman Nellie Fox to give the White Sox a tremendous double-play combination. They led Chicago to the team’s first pennant since the 1919 “Black Sox.”

Aparicio was a steady but not overpowering hitter. He hit over .300 only once, in 1970. But he had 20 or more doubles 14 times in his career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .262, HR: 83, RBI: 791, H: 2,677, SB: 506

#131 John Gibson Clarkson

RHP, Worcester, White Stockings, Braves, Spiders, 1882–94. Hall of Fame, 1963

Clarkson pitched in the era of two-man staffs, and his statistics reflect that. In 1885 he completed 68 of 70 starts in winning 53 games. That’s a tidy 623 innings. In the next four years he won 36, 38, 33 and 49 games, for an average of 40 wins per season.

Although the perception these days is that workhorse pitchers like Clarkson relied on guile to win games, in reality, Clarkson was primarily a fastball pitcher with an excellent curve. The year he won 53 games, his ERA was 1.85 and he posted a league-leading 10 shutouts.

But like most 19th-century pitchers, Clarkson’s peak years were few: 1885–92. And his fall was precipitous. He developed arm trouble in 1892, and hung on for only two more years before retiring.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 328, L: 128, SV: 5, ERA: 2.81, SO: 1,978, SB: 485

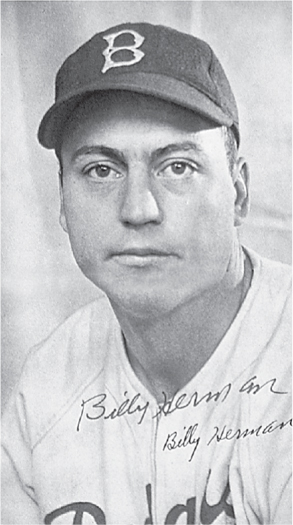

#132 William Jennings Bryant “Billy” Herman

2B-3B, Cubs, Dodgers, Braves, Pirates, 1931–47. Hall of Fame, 1975

One of the great all-around second baseman of his era, Herman was an expert at the hit-and-run play. Many observers say he was the best practitioner of the hit-and-run in baseball history, which is saying something.

He was a 10-time All Star, and he anchored the infield of the last great Cub dynasty of the 1930s, those heady days when the Cubs won National League pennants in 1932, 1935 and 1938.

He was a great defensive player, leading the league in fielding percentage in 1935, 1936 and 1938. But he was also an excellent hitter, topping .300 eight times in his career. He was, Leo Durocher once said, “the absolute master at hitting behind the runner.”

Herman hit .433 in 10 All Star games (13 for 30).

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .304, HR: 47, RBI: 839, H: 2,345, SB: 67

#133 Leon Day

P-2B-OF, Baltimore Black Sox, Brooklyn Eagles, Newark Eagles, Baltimore Elite Giants (Negro Leagues), 1934–50. Hall of Fame, 1995

The best pitcher in the Negro Leagues in the late 1930s and 1940s, Day was a strikeout king who was also an excellent fielder and solid hitter.

Day had an outstanding fastball and excellent control. He set strikeout records in three venues. Pitching for the Newark Eagles, Day fanned 18 Baltimore Elite Giants in 1942, allowing only a bloop hit. A year earlier, playing in the Venezuelan League, he had struck out 19 batters to set another league record. And in seven Negro League All Star games, he set a career strikeout record with 14.

Day also was a regular .300 hitters with most of the teams on which he played, and was often used in the field when he wasn’t pitching.

Following his retirement from the Negro Leagues, Day played for years for various minor leagues.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 68, L: 30

#134 Monford Merrill “Monte” Irvin

OF-1B, Newark Eagles (NL), Giants, Cubs, 1938–56. Hall of Fame, 1973

Monte Irvin began his pro career in the shadows of the Negro Leagues and finished it in the bright lights of pro baseball.

Irvin was a fleet-footed shortstop for the Newark Eagles and led that team to the Negro League World Series championship over Satchel Paige’s Kansas City Monarchs.

He was drafted by the New York Giants in 1949 and, in 1951, hit .312 and led the league in RBI with 121 as the Giants won the pennant. In the World Series against the Yankees, Irvin led both teams with 11 hits, a .458 average and two stolen bases, including a steal of home.

Irvin played seven years in New York before finishing up his career in Chicago, hitting a very respectable .271.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .293, HR: 99, RBI: 443, H: 731, SB: 28 (Note: MLB totals only)

#135 Edward Augustine “Big Ed” Walsh

RHP, White Sox, Braves, 1904–17. Hall of Fame, 1946

Almost a century ago, the Chicago White Sox engineered one of the greatest upsets in baseball history, winning the 1906 World Series. And Big Ed Walsh was the main reason, winning both his starts and posting a minuscule .60 ERA and 17 strikeouts.

Walsh was the Catfish Hunter of the early part of the 20th century: A tough, smart durable pitcher who wanted the ball in big games.

In 1908, Walsh went 40–15, starting 66 games and finishing 42. He had 11 shutouts, six saves and struck out 269, all league highs. He also pitched 464 innings, still an American League record. The White Sox finished third that year, 11/2 games behind Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers. Walsh pitched in seven games in the final nine days of the season in an attempt to get the White Sox back to the World Series.

In addition to being one of the top starters for the White Sox at the turn of the 20th century, Walsh was also a top reliever, leading the league in saves five times.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 195, L: 126, SV: 34, ERA: 1.82, SO: 1,736, SB: 315

#136 Roger Phillip “The Duke of Tralee” Bresnahan

C, Washington, Cubs, Orioles, Giants, Cardinals, 1897–1915. Hall of Fame, 1945

In his time, Bresnahan was deemed the greatest catcher ever. He was a good hitter (three seasons over .300), an excellent base runner (he stole 212 bases in his career) and a canny receiver.

Contrary to legend, Bresnahan did not invent the batting helmet in 1903; the A.G. Spalding Co. were already marketing them. But he legitimized it. He did not invent shin guards, either. Many infielders were using them long before he donned them in 1905. But again, because Roger Bresnahan, star catcher for the Giants used them, it meant everyone else could, too.

And he didn’t invent the catcher’s mask. That was already in use. He did improve on it after he donned one for good in 1908. Basically, he was trying to find ways to protect himself from injury and catch more games.

In 1945, Bresnahan became the first catcher to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Bresnahan’s nickname is “The Duke of Tralee,” after a town in Ireland that was supposedly Bresnahan’s birthplace. Actually, he was born in Toledo.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .279, HR: 26, RBI: 530, H: 1,252, SB: 212

#137 Stanley Camfield “Smiling Stan” Hack

3B, Cubs, 1932–47

A vastly underrated third baseman during the 1930s and 1940s, Hack was an excellent leadoff hitter for the Chicago Cubs, seven times scoring 100 runs or more. He led the National League in hits twice, in 1940 and 1941.

A four-time All Star, Hack also led the league in stolen bases in 1938 and 1939. In four World Series, his batting average was .348. His lifetime average was .301.

Despite leading the league’s third basemen in fielding percentage twice and finishing second or third five other times, Hack was never recognized as the stellar fielder that he was.

Fast fact: Hack actually retired near the end of 1943 because he couldn’t get along with Cub manager Jimmy Wilson. Wilson was fired in early 1944 and Charlie Grimm was hired. Grimm coaxed Hack out of retirement, and in 1945, Hack hit .323 to lead the Cubs to the National League pennant.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .301, HR: 57, RBI: 642, H: 2,193, SB: 165

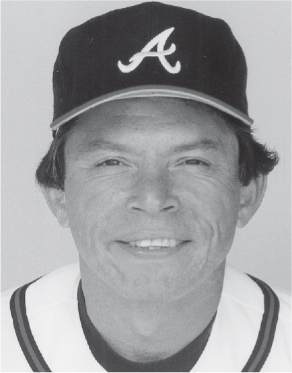

#138 Dale Bryan Murphy

OF-1B, Braves, Phillies, Rockies, 1976–93

Murphy was one of the best players in the game in the 1980s, becoming the youngest player ever to win back-to-back MVP awards in 1982 and 1983.

Murphy started his major league career as a catcher, but was eventually moved to the outfield with the Braves. He was low-key, likeable and a great hitter. A seven-time All Star, he twice led the league in home runs, in 1984 and 1985.

Murphy was primarily a slugger, but he was patient, leading the league in walks in 1985 and three other times topping 90 bases on balls.

He was a five-time Gold Glove winner in the outfield. He also could run a little, and in 1983 stole 30 bases and hit 36 home runs, placing him in the elite “30–30" category.

Murphy played in 740 consecutive games from September of 1981 to July of 1986.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .265, HR: 398, RBI: 1,266, H: 2,111, SB: 161

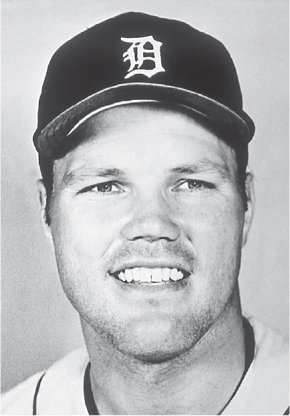

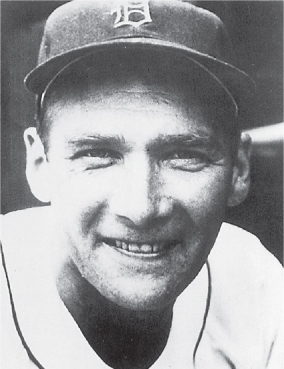

#139 Alan Stuart Trammell

SS-DH, Tigers, 1977–96

One of the great all-around players of the 1980s. The six-time All Star hit .300 or better seven times and won four Gold Gloves while holding down the shortstop position for Detroit for most of his 20 seasons in a Tiger uniform.

Trammell was a self-made superstar. He was not a good hitter initially, but his tireless work ethic in the off-season paid off. His anemic home run totals in the first six years of his career steadily improved until he popped a career-high 28 in 1987.

He was a good base runner. His 30 steals in 1983 were the most by a Tiger shortstop since a fellow named Cobb stole 34 in 1917.

Trammell was MVP of the 1984 World Series with a .450 average and nine hits in five games.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .285, HR: 185, RBI: 1,003, H: 2,365, SB: 236

#140 David Mark “Dave” Winfield

OF-DH, Padres, Yankees, Angels, Blue Jays, Twins, Indians, 1973–95. Hall of Fame, 2001

At 6'2", 220 pounds, big Dave Winfield looked like an All Star. Which he was, having been named to the All Star team 12 times.

Winfield didn’t put up explosive numbers most of his career, but he was, when healthy, incredibly consistent. He never won a home run crown, but socked 465 in his career. He never had more than 193 hits in a season, but ended up with 3,110.

Winfield was also a stellar fielder, winning seven Gold Glove awards. His outfield arm was one of the most accurate in the game, although ironically, that arm gained most of its notoriety when Winfield accidentally killed a seagull with a throw in Toronto.

However well he played, though, team success eluded Winfield until he was traded to Toronto in 1992. In his one year with the Blue Jays, Winfield played in the outfield and was a DH for the World Champions.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .283, HR: 465, RBI: 1,833, H: 3,110, SB: 1,686

#141 Thurman Lee “Tugboat,” “Squatty Body,” “The Wall” Munson

C-OF, Yankees, 1969–79

Munson, despite what Reggie Jackson may claim, was the anchor of those late 1970s Yankee teams that won three AL titles in a row.

Munson was squat and looked a little dumpy in uniform, but that hid an athlete’s body. He was one of the fastest catchers of all time and was very quick. He was one of the best in the league at covering bunts.

Munson, a seven-time All Star, hit over .300 in five seasons, and won three Gold Glove awards. He was league MVP in 1976, when he hit .302 with 105 RBI and 17 home runs as the Yankees won their first pennant of the 1970s.

Munson was still a fine ballplayer in 1979, but on August 2 of that year, the plane he was piloting crashed near Cleveland, killing him. Munson hit .373 in World Series play.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .292, HR: 113, RBI: 701, H: 1,558, SB: 48

#142 Tony (Pedro) Oliva

OF-DH, Twins, 1962–76

Oliva remains the only player in major league history to win batting championships in his first two full years in the major leagues. Oliva had two brief stints with the Twins in 1962 and 1963. He hit .444 in nine games in 1962 and .429 in seven games the next year.

Finally, he came up for good in 1964, and just exploded. He had 217 hits, scored 109 runs, smacked 43 doubles and hit .323, all of which led the league. Not surprisingly, he was Rookie of the Year. But sportswriters of the 1960s didn’t give MVP awards to rookies, even ones as good as Oliva. In fact, Oliva finished fourth behind Brooks Robinson, Mickey Mantle and Elston Howard.

No matter. Oliva proved it wasn’t a fluke, hitting .321 to win the batting title again. He also led the league with 185 hits.

An eight-time All Star, Oliva would win one more batting title, but the smooth-swinging Cuban would hit .300 or better seven times in his career, make 190 or more hits four times in his career and lead the league in doubles four times. He won a Gold Glove award in 1966.

Injuries hampered his career in the 1970s, but Oliva still hit well enough to finish with a career average above .300.

Oliva’s real name is Pedro, but he arrived in the United States on his brother’s passport, in 1961, and has been known as Tony ever since.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .304, HR: 220, RBI: 947, H: 1,917, SB: 86

#143 Andre Nolan “The Hawk” Dawson

OF-DH, Expos, Cubs, Red Sox, Marlins, 1976–96. Hall of Fame, 2010

Dawson was a solid performer while with the Expos: a three-time All Star who hit .300 or better three times with Montreal, possessing excellent power.

He was also an excellent fielder, winning six consecutive Gold Gloves with the Expos, from 1980 to 1985. The Hawk could run, too, stealing 20 or more bases seven times while in Montreal.

But Dawson was traded to the Cubs in 1987 and took things up a notch. That first year, Dawson smacked a league-leading 49 home runs and added a league-best 137 RBI. Dawson also hit .287 with 24 doubles.

The numbers won him the MVP award, even though there were some grumblings that Dawson was playing with a last-place team. He remains the only MVP winner to play for a cellar-dweller.

Dawson was named to the All Star team five times in Chicago, and hit .300 or better twice more. He also won two more Gold Gloves, in 1987 and 1988. In 1993, it was on to the Red Sox, where he had two more good years, primarily as a designated hitter.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .279, HR: 438, RBI: 1,591, H: 2,774, SB: 314

#144 Keith “Mex” Hernandez

1B-OF, Cardinals, Mets, Indians, 1974–90

Hernandez won 11 consecutive Gold Gloves at first base, from 1978 to 1982 with the Cardinals and from 1983 to 1988 with the Mets. He was one of the best-fielding first basemen of all time.

His strength in the field was his amazing range. The agile six-footer led the league’s first basemen in assists five times, putouts four times and fielding percentage twice. He is second to Eddie Murray in assists all-time with 1,682.

But Hernandez could also hit pretty well. In his 17-year career, Hernandez hit .290 or better 11 seasons. In 1979, he won the batting title, hitting .344 with St. Louis. That same year, his on-base percentage was .417, second-best in the league, and his 116 runs scored topped the circuit. Those stats, plus his stellar fielding, earned him the MVP award that year.

Hernandez was a key contributor to the Mets’ championship drive in 1986, hitting .310 during the regular season and leading the league in walks. In fact, his on-base percentage was above .400 six times in his career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .296, HR: 162, RBI: 1,071, H: 2,182, SB: 98

#145 William Nuschler “Will the Thrill” Clark

1B-DH, Giants, Rangers, Orioles, Cardinals, 1986–2000

The rangy Clark hit .300 or better four times for the San Francisco Giants. He hit a career-high 35 home runs for San Francisco in 1987, and drove in a career-high 116 runs in 1991.

In the late 1980s, Clark was one of the best players in the National League. He finished in the top five in the MVP voting three years in a row, from 1987 to 1989. He led the league in RBI in 1988 with 109 and led the league in runs scored in 1989 with 104.

In the 1989 National League Championship Series against the Cubs, Clark was phenomenal, hitting .650 in five game, with 13 hits, eight RBI, three doubles, a triple and two home runs.

In 1991, Clark hit .301 with 116 RBI, 29 home runs and 32 doubles. He also won his only Gold Glove at first base.

A trade to Texas saw Clark continue his solid hitting. Clark spent five years with the Rangers and hit .300 or better four times, although his power numbers dropped.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .303, HR: 284, RBI: 1,205, H: 2,176, SB: 67

#146 Kirby Puckett

OF-DH, Twins, 1984–95. Hall of Fame, 2001

Puckett was built like a fireplug with legs, and generated tremendous power from that relatively small frame. As a 23-year-old rookie with the Twins in 1984, Puckett hit .296 with 165 hits in 128 games.

He became the ninth player in major league history to debut with four hits in a nine-inning game, and his 16 assists from the outfield led the league.

Puckett had a little trouble figuring out big league pitching, and didn’t hit a home run in his first season, and only socked four in 1985. But he clearly figured things out by 1986, and belted 31. After that, Puckett hit 12 or more home runs eight of the next nine years.

In 1989, he won his only batting title, hitting .339. But Puckett hit .300 or better eight times in his career, and in fact hit .325 or better five times. Five times, he made 200 or more hits, leading the league four times.

Puckett didn’t look particularly graceful when he ran, but he still managed to collect six Gold Glove awards. He was also a better base-stealer than he gets credit for, swiping 10 or more bases seven times.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .318, HR: 207, RBI: 1,085, H: 2,304, SB: 134

#147 Theodore Amar “Ted,” “Tex,” “The Baylor Bearcat” Lyons

RHP, White Sox, 1923–46. Hall of Fame, 1955

Lyons, who never spent a day in the minors, was a 20-game winner only three times in his 21-year career. But he was a consistent pitcher for a Chicago team that was, for the most part, not very good during his tenure. Lyons in fact never made it to a World Series.

He was durable, though, pitching 200 or more innings 10 times in his career, and leading the league twice, in 1927 and 1930.

Lyons was always a control pitcher, rarely walking more than 70 batters a season. He walked only 1,121 batters in 4,161 innings in his career, and in 1939, Lyons threw 42 consecutive innings without walking a batter.

In 1931, he battled arm miseries, and for the next two years, his effectiveness decreased. But he learned to throw a knuckleball, and was 15–8 in 1935, his first winning season in four years.

Lyons was a tremendously popular pitcher, so much so that in his later years, Sox managers would pitch him exclusively on Sundays, to take advantage of his drawing power with the fans. In 1942, on just 20 starts, Lyons was 14–6 with a league-leading 2.10 ERA.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 260, L: 230, SV: 23, ERA: 3.67, SO: 1,073, CG: 356

#148 Albert Jojuan “Joey” Belle

OF-DH, Indians, White Sox, Orioles, 1989–2000

Belle was one of the best players in baseball in the mid- to late-1990s, a power hitter with speed who consistently drove in runs.

After two desultory seasons in Cleveland, Belle broke out, hitting .282 in 1991, with 31 doubles, 28 home runs and 95 RBI. From 1993 to 1996, he was a holy terror, leading the league in RBI three years and hitting over .300 three consecutive seasons.

He was third in the MVP balloting in 1994 and 1996 and second in 1995.

The 1995 season was Belle’s best, statistically. He led the American League with 50 home runs, 52 doubles, 121 runs scored, 126 RBI and a .690 slugging percentage. Belle, a surly cuss for the most part, lost the award to Boston’s Mo Vaughn, a more affable man who had good numbers of his own, but not as good as Belle’s that year. Interestingly, the two teams met in the playoffs. Belle hit .235; Vaughn was hitless in 14 at bats as the Indians swept the series.

After another solid season in Cleveland, Belle went over to the White Sox in 1997. He had a strong season in 1998, leading the league in slugging percentage with a .655 mark, total bases with 399 and sacrifice flies with 15. He was second in home runs with 49, second in doubles with 48 and third in batting average with a .328 mark. Yet again, his surliness cost him many MVP votes, and Belle was eighth.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 381, RBI: 1,239, H: 1,726, SB: 88

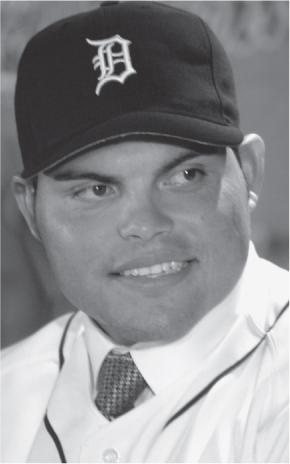

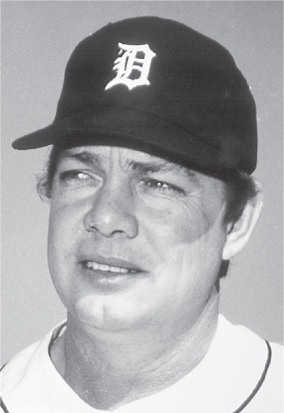

#149 William Ashley “Bill” Freehan

C-1B-DH, Tigers, 1961–76

Freehan was one of the best defensive catchers of his era, winning five Gold Gloves and leading American League catchers in fielding percentage three times.

Freehan, a Detroit native, was playing football at the University of Michigan when he signed with the Tigers in 1961. By 1964, he was the team’s regular catcher. He hit .300 that year, the only season he would attain that mark. Freehan also had a career-high 80 RBI.

In 1968, Freehan hit 25 homers and had a .263 batting average, as the Tigers won their first World Series over the Cardinals. Freehan ended the series by catching Tim McCarver’s pop-up in Game Seven.

Freehan was a tough cookie who crowded the plate and was frequently hit by pitchers. In 1968, he was hit by a record 24 pitches, including three plunks in a game in August.

Freehan’s real strength was his work behind the plate, handling pitchers, throwing out base-stealers and fielding bunts. In 1965, he tied a major league record for catchers with 69 putouts.

Freehan remains the career leader in fielding percentage by a catcher, with a .993 mark. He is also fifth in career putouts with 9,941.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .262, HR: 200, RBI: 758, H: 1,591, SB: 24

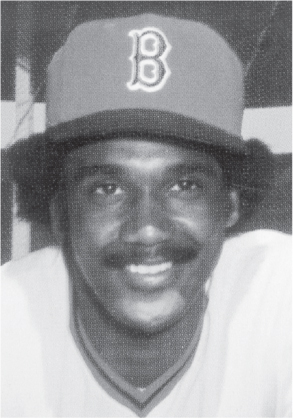

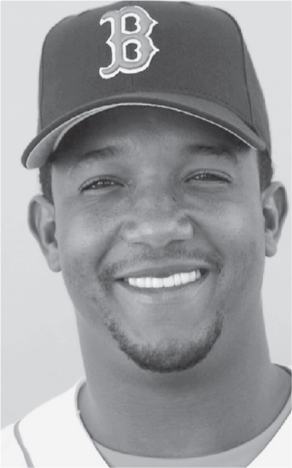

#150 James Edward “Jim” Rice

OF-DH, Red Sox, 1974–89. Hall of Fame, 2009

Rice, in the late 1970s, was a one-man wrecking ball for the Red Sox. He came up in 1975, along with fellow rookie Fred Lynn. That season, Lynn got all the headlines, winning the Rookie of the Year and the MVP award. But while Lynn had a hard time duplicating his first season, Rice, who was no slouch himself in 1975, just seemed to get better and better.

In 1978, he was MVP, and deservedly so. Although this was also the year that the Yankees’ Ron Guidry was 25–3, Rice was, day in and day out, the best player in either league. He hit .315, with a league-leading 46 home runs, 139 RBI, 15 triples and 213 hits. His 406 total bases were the highest in the league since Joe DiMaggio’s 418 in 1937.

Rice hit .300 or better seven times in his career, had 20 or more homers 11 times, 100 or more RBI eight times and 200 or more hits four times.

He hit .333 in his only World Series in 1986 (he broke his wrist just before the 1975 playoffs), with six runs scored.

Rice was relatively slow afoot, and had a penchant for grounding into double plays. He grounded into 36 doubles in 1984, a major league record at the time.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .298, HR: 382, RBI: 1,451, H: 2,452, SB: 58

#151 Edd J. Roush

OF-1B, White Sox, Indianapolis (FL), Newark (FL), Giants, Reds, 1913–31. Hall of Fame, 1986

Roush was one of the best hitters of the 1910s and ’20s, a strong guy who was not afraid to spike opposing players on the base paths, and then dare them to retaliate.

Roush bounced around the major leagues for the first four years of his career, playing for five teams in that span. But when he came to Cincinnati, he found a home. Roush was installed at center field, and became a star, hitting .300 or better 10 times in his 11 years with the Reds.

Roush would hit .300 or better 13 times overall. He would win batting titles in 1917, when he hit .341, and in 1919, when he hit .321.

Roush also led the league in doubles with 41 in 1923, and in triples with 21 in 1924. He would hit 20 or more doubles eight times in his career and 10 or more triples 11 times. He was also a pretty good base-stealer, swiping 10 or more bases 12 times.

The 1919 season was the year Roush led the Reds into the World Series against the White Sox. Cincinnati won the series, five games to three (in those days it was a best-of-nine series), and Roush never believed the Sox were lying down against him.

Roush used a big, thick bat, and most opponents believed it was to enable Roush to sock homers. They were wrong. The canny Roush was a tremendous bunter and slap hitter. Reportedly, Roush owns the record for most hits on a pitchout, making seven one year.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .323, HR: 68, RBI: 981, H: 2,376, SB: 268

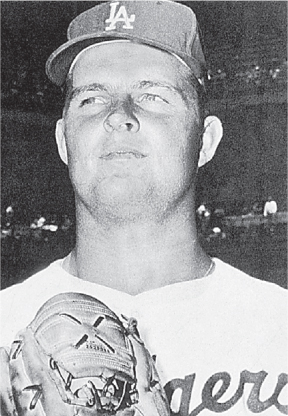

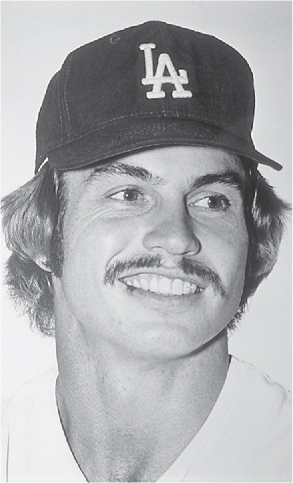

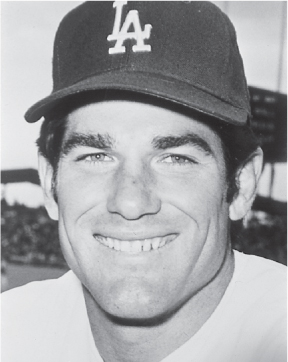

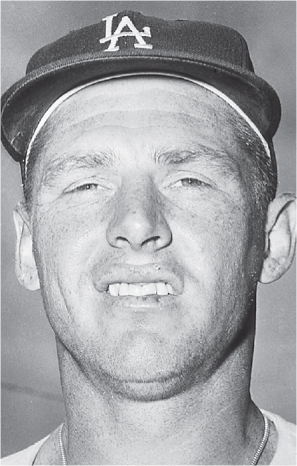

#152 Donald Scott “Don” Drysdale

RHP, Dodgers, 1956–69. Hall of Fame, 1984

The towering (6'6") Drysdale was an intimidating presence on the mound, for several reasons. First, he was a sidearm pitcher with excellent control. His delivery meant the ball came at batters from a difficult angle. Second, Drysdale was not afraid, and in fact was happy, to pitch inside on batters.

Drysdale set a 20th-century record by hitting 154 batters, and led the league in that department a record five times. He would often refer to his knockdown pitches as “kisses.”

But Drysdale was much more than a knockdown artist. He led the league in strikeouts three times, and had 200 or more strikeouts in a season six times. A workhorse who hated to come out of games, he pitched 300 or more innings in a season four times.

He also led the league in shutouts in 1959. In 1968, he threw six consecutive shutouts, and a since-broken 58 2/3 shutout innings.

An excellent hitter, Drysdale twice tied the major league record for home runs by a pitcher, with seven. His career total of 29 is second all-time. In 1965, he hit .300 and was one of the best pinch hitters on the Dodgers.

Drysdale was a terrific pitcher in the All Star game, with a 2–1 mark overall, and a record 1.40 ERA with 19 strikeouts.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 209, L: 166, SV: 6, ERA: 2.95, SO: 2,486, CG: 167

#153 William Robert “Sliding Billy” Hamilton

OF, Kansas City (AA), Phillies, Braves, 1888–1901. Hall of Fame, 1961

Hamilton combined speed, smarts and aggressiveness on the base paths to become one of the premiere players of the 19th century.

Hamilton started out in the old American Association, where he hit .301 for Kansas City in 1889. That began a string of hitting .300 or better for 12 consecutive years. Hamilton signed with the Phillies in 1890 and won the National League batting title with a .340 average the following year. Ironically, Hamilton would top that mark six more times (in fact, his career batting average is .344, sixth best all-time) but never won another batting crown.

In addition to being a solid hitter, Hamilton had an excellent eye at the plate. He led the league in walks five times.

He was a run-scoring machine, four times topping the league in that category. In 1894, Hamilton scored a record 192 runs in 129 games, hitting .404 and walking a league-best 126 times.

Hamilton stole 100 or more bases three times in his career, and led the league in thefts five times. He was called “Sliding Billy” for his baserunning feats. He also had 20 or more doubles seven times in his career.

Hamilton ended his 14-year career as one of only three men to have more runs (1,690) than games played (1,591).

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .344, HR: 40, RBI: 736, H: 2,158, SB: 912

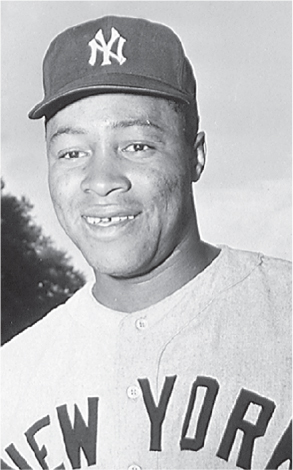

#154 Lawrence Eugene “Larry” Doby

OF, Indians, Tigers, White Sox, 1947–59. Hall of Fame, 1998

Doby is now a historical asterisk, which is unfortunate. The first black player to play in the American League (Jackie Robinson integrated baseball in the National League), Doby was also a very good player: an excellent hitter and a sure-handed outfielder with great range.

He was signed by the Cleveland Indians in 1947, just four months after the Dodgers signed Robinson. Doby was surely subjected to as many racial indignities as Robinson, but his low-key demeanor did not attract as much media attention.

Prior to his signing, Doby was a budding star in the Negro Leagues, hitting .341 and .414 in his first two years with the Newark Eagles.

Doby, like Robinson, preferred to let his playing talk for him. He hit .301 to lead the Indians to the World Championship in 1948 and picked up the pace in the World Series, hitting .318.

Doby led the AL in home runs (32) and RBI (126) in 1954, and finished a close second to Yogi Berra in the MVP voting. In Cleveland’s pennant-winning year of 1954, Doby again led the league in homers with 32 and in RBI with 126. Five times in his career, Doby had 100 or more RBI.

Doby’s big swing left him vulnerable to strikeouts, and in fact, he fanned 100 or more times four times in his career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .283, HR: 253, RBI: 970, H: 1,515, SB: 47 (MLB stats only)

#155 George Stacey Davis

SS-3B-OF, Cleveland (NL), Giants, White Sox, 1890–1909. Hall of Fame, 1998

Davis began his career as a third baseman for the Cleveland Naps and then the Giants of the National League, but then was switched to shortstop. He was a solid performer at both positions, but was clearly a better fielder as a shortstop than a third baseman.

He was also a switch-hitter, and one of the best in the 19th century. He hit 27 triples in 1893, still a record for a switch-hitter.

Davis hit .300 or better for nine consecutive years, including a career-high .353 in 1897. That same year, Davis led the National League in RBI with 136.

An excellent base runner, Davis stole 20 or more bases 17 times in his career. His career high was 65, also accomplished in 1897.

Davis led the league’s shortstops in fielding percentage twice in the National League and twice in the American League, after he had been traded to the White Sox. In 1906, he led the White Sox’s “Hitless Wonders” to the World Championship, upsetting the heavily favored Chicago Cubs. Davis was definitely not a hitless wonder: He hit .308 with three doubles, four runs scored and six RBI in the series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 73, RBI: 1,437, H: 2,660, SB: 616

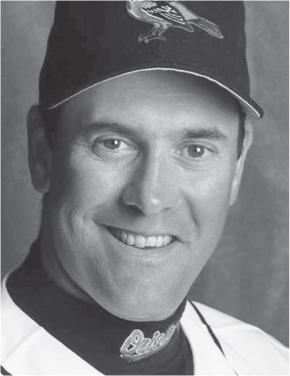

#156 Roberto “Robby,” “Bobby” Alomar

2B-DH, Padres, Blue Jays, Orioles, Indians, Mets, White Sox, Diamondbacks, 1988–2004. Hall of Fame, 2011

Bobby Alomar is a 12-time All Star with 10 Gold Glove awards on his resume. In addition he is an excellent hitter, with nine seasons hitting .300 or better.

Orlando Cepeda once compared Alomar favorably to Joe Morgan, Rod Carew and Cool Papa Bell.

Truthfully, he doesn’t hit as well as Morgan or Carew, but he’s close. And he doesn’t run as well as Bell, but maybe nobody ever did. Suffice to say that Alomar has played at a high level from the 1990s into this century.

His biggest problem is that when people think of Robby Alomar, they don’t think of Gold Gloves or .300 seasons. They remember the last weekend of the 1996 season, when a frustrated Alomar spat on umpire John Hirschbeck. It’s sort of the curse of ESPN, if you will. But Alomar is a good one who could be a great one if he keeps it up.

Alomar hit .400 or better in three postseason series: the 1991 ALCS, the 1992 ALCS and the 1993 World Series.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .300, HR: 210, RBI: 1,134, H: 2,734, SB: 474

#157 Jacob Nelson “Nellie,” “Little Nel” Fox

2B-3B, Athletics, White Sox, Astros, 1947–65. Hall of Fame, 1997

Fox was a part-time player for three years with the Athletics, and had a relatively unremarkable career there. But he was traded to the White Sox, and his career took off. Fox became Chicago’s regular second baseman, and was hard to dislodge, playing in 798 consecutive games there from August 7, 1956, to September 3, 1960.

But more than his durability, Fox was a tremendous defensive second baseman. Six times, he led second basemen in fielding percentage, and he won three Gold Gloves. He teamed up with Chico Carrasquel and later Luis Aparacio to give Chicago a strong defensive presence in their middle infield.

Fox had six seasons where he hit .300 or better, and he also led the league in hits four times. Six times, he made 190 or more base hits.

Not necessarily a threat to steal bases, Fox was nonetheless aggressive on the base paths. He stroked 20 or more doubles 11 times and 10 or more triples four times. He led the league in triples with 10 in 1960.

Fox was very tough to strike out. He never had more than 18 strikeouts in a full season, and ended up with only 216 on his career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .288, HR: 35, RBI: 790, H: 2,663, SB: 76

#158 Philip Henry “Phil” Niekro

RHP, Braves, Yankees, Indians, Blue Jays, 1964–87. Hall of Fame, 1997

When the 48-year-old Niekro finally retired, he was the oldest player to perform regularly in the major leagues. Niekro rode his mastery of the quirky knuckleball into the Hall of Fame.

The 300-game winner was consistent and durable throughout his 24-year career. He won 20 games only three times, and led the league in that department only once, in 1974 when he was 20–13.

Because the knuckler didn’t take a lot out of his arm, Niekro was durable. He threw over 300 innings four times, and tossed more than 250 seven other times. He led the league in complete games four times, with a career-high of 23 in 1979.

Niekro also has a lot of success striking out batters with the knuckler. He led the league with 262 punchouts in 1977, and had 190 or more strikeouts four other times.

Yet his prowess, perhaps because it was with the knuckler, was often taken for granted. He was chosen for only five All Star games, and only pitched in two, throwing a total of 1 1/3 innings.

Yet he pitched well, for good teams and not-so-good teams. At age 43, he was 17–4 for the Braves and led the league with an .810 winning percentage. In 1985 and 1985, he was a solid 32–20 for the Yankees.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 318, L: 274, SV: 29, ERA: 3.35, SO: 3,342, CG: 245

#159 Fredric Michael “Fred” Lynn

OF-DH, Red Sox, Angels, Orioles, Tigers, Padres, 1974–90

Wow. How about that first season, huh?

Fred Lynn burst into the limelight in Boston with a stunning season in which he won the Rookie of the Year award and MVP, a feat never accomplished before or since.

And he deserved it. Lynn hit .331 and slugged a league-leading .556, with 47 doubles and 103 runs scored, also league bests. He also had 21 homers and 105 RBI.

Lynn’s swing was tailor-made for the left-field wall in Fenway Park, but he was no slouch on the road, either. On June 18 of his rookie season, he drilled three homers and had 10 RBI and 16 total bases against the Tigers.

In his six years in a Boston uniform, Lynn hit .300 or better four times (and hit .298 in 1978), won a batting title in 1979 with a .333 mark, hit 124 home runs and made the All Star team every year.

His failure to keep up that standard was actually a tribute to his hustle. Lynn was also an amazing defensive outfielder, but his all-out play often had him slamming into walls. He was frequently injured his last few years with the Sox, and when he was finally signed by the Angels, he wasn’t the Fred Lynn of old.

He was certainly pretty decent, however. Lynn hit .299 with 21 home runs for the Angels in 1982, and .287 in 1986 with the Orioles. He made the All Star team three times with California.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .283, HR: 306, RBI: 1,111, H: 1,960, SB: 72

#160 Martin DiHugo

2B-RHP-OF-SS-3B-1B-C, Cuban Stars, New York Cubans, Homestead Grays, Hilldale Daisies, Darby Daisies (Negro Leagues), 1923–36. Hall of Fame, 1977

DiHugo was an exceptional athlete who may have been the most versatile baseball player ever. He was a man who could—and did—play every position on the diamond at some point in his career, including pitcher.

DiHugo had a very strong arm, was very fast on the base paths and in the outfield, and had a natural confidence in his abilities, enabling him to excel wherever he played.

He began as an infielder in his native Cuba, but as was often the case in semipro teams of the 1920s in Cuba, he was also asked to play first and third base, and take a turn in the outfield. DiHugo would do so, and usually turn in an outstanding performance.

He was signed by the Cuban Stars of the Eastern Colored League in 1923, and began his pitching career. The Cubans were not a strong team, but DiHugo played the infield, hitting .299 in 1925, and pitching. In 1927, he led the league in home runs and was 2–2 on the mound.

He was also going back to Cuba and playing winter ball. He hit .413 and .415 in consecutive seasons for the Havana Sugar Kings in 1927 and 1928.

DiHugo began pitching more as he got older, preferring to let younger players toil in the field. By 1937, he was 32, and a veteran of 10 seasons in the Negro Leagues and eight in the Cuban Leagues. That year, he went 11–5 for Havana, and the next year, was 18–2. He had a good, but not overpowering fastball, and a very good curveball. He pitched the first no-hitter in the Mexican League in 1939.

DiHugo was elected to the Halls of Fame in Mexico and Cuba as well as the United States Hall of Fame.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .299, HR: 69, H: 1,609

#161 Lewis Robert “Hack” Wilson

OF, Giants, Cubs, Dodgers, Phillies, 1923–34. Hall of Fame, 1979

For many years, Hack Wilson was a trivia question, as in, Who holds the single-season National League record for most home runs (56) and Who still holds the major league record for RBI (191)?

Wilson was 5'6", and weighed 190 pounds. But he was all muscle. He had an enormous upper body, huge, Popeye-like forearms and a barrel chest. His body tapered down to spindly ankles and a size-six cleat.

But he could hit. His nickname actually came from his resemblance to journeyman Hack Miller, who played for the Giants before Wilson came on the scene. He was a better hitter than Miller; he was a better hitter than almost anyone. Wilson led the league in home runs four times, including the aforementioned 56 dingers in 1930, a record that was not broken until Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa each bested it in 1998.

His 191 RBI mark, also set in 1930, is still untouched, and there have not been a lot of challengers in the ensuing 74 seasons.

But he was not just a slugger. He had a 27-game hitting streak in 1931, and hit for the cycle in 1930.

In the outfield, he was better than most thought. He led the league in 1927 with 400 putouts and had enough speed to make a lot of plays.

But his battles with the bottle were legendary. Several mangers tried to wean him of it; none succeeded. Wilson died nearly broke at age 48.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .307, HR: 244, RBI: 1,063, H: 1,461, SB: 52

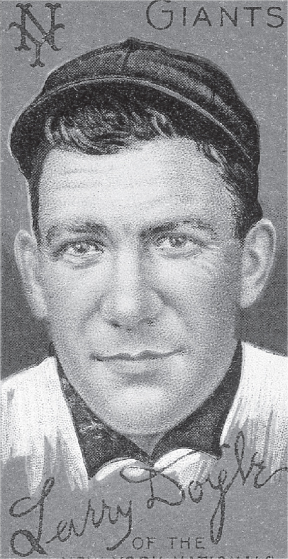

#162 Joseph Lowell “Joe,” “Flash” Gordon

2B, Yankees, Indians, 1938–43, 1946–50. Hall of Fame, 2009

Gordon was a great athlete, and had excellent range at second base. He tried to get every ball hit close to him, and was a hustler both at bat and in the field.

As a rookie, he displaced future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri at second base, and there was little doubt that he had earned it. He was a better defensive player than Lazzeri, and hit .255 with 25 home runs and 97 RBI that year.

Gordon hit .300 or better only once, but he had over 100 RBI four seasons, 20 or more home runs seven times, 20 or more doubles eight times and scored 100 or more runs twice.

Gordon was the MVP of the league in 1942, hitting .322 with 18 home runs, 103 RBI and 88 runs scored. He hit for the cycle in 1940.

His postseason work was also mostly successful. Gordon played in five World Series with the Yankees and one with Cleveland. He had two doubles and a home run to go along with a .400 batting average for New York in 1939, and hit .500 with a home run and seven RBI in the 1941 series.

Traded to the Indians in 1947, Gordon hit .280 with 32 home runs and 124 RBI in 1948 to lead Cleveland to the pennant and world championship over the Boston Braves.

#163 Louis Rodman “Lou,” “Sweet Lou” Whitaker

2B-DH, Tigers, 1977-95

In the field, Whitaker made defensive plays that were seemingly effortless, leading critics to decide he wasn’t trying. Well, he had to be doing something right: He ranks ninth all-time among second basemen in runs scored (1,386) and RBI (1,084).

Whitaker was the Rookie of the Year in 1978, hitting .285 with 58 RBI and 71 runs scored. A down year in 1980, in which he hit only .233 with one home run, led many Tiger fans to conclude that he was something of a fluke. But Whitaker erased all that criticism over the next decade, making the All Star team five consecutive times and, in 1983, hitting .320 and becoming the first Tiger to make 200 or more hits since 1943.

His power numbers steadily increased, and in 1985, Whitaker set a team record for second basemen with 21 home runs. He later shattered that mark with 28 in 1989. In all, Whitaker hit 20 or more home runs four times for the Tigers.

Defensively, Whitaker led the league’s second basemen in fielding average twice, in 1982 and again in 1991. He was usually among the leaders in most defensive categories throughout the 1980s.

In the World Series of 1984, which the Tigers won over the Padres, Whitaker led the team with six runs scored and two doubles.

As the 1990s dawned, Whitaker was used as a part-time player more and more. But he was still effective, hitting .290, .301 and .293 in his last three seasons.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .276, HR: 244, RBI: 1,084, H: 2,369, SB: 143

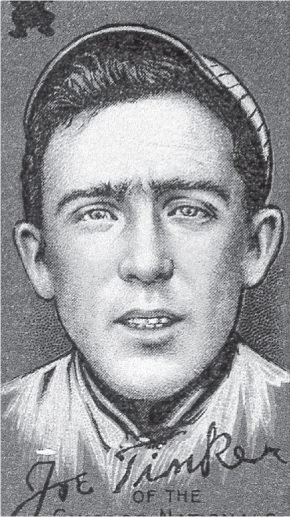

#164 Frank Leroy “Husk,” “The Peerless Leader” Chance

1B-C-OF, Cubs, Yankees, 1898–1914. Hall of Fame, 1946

Chance was, of course, the first baseman in the famed “Tinker to Evers to Chance” double-play combination of legend. He was nicknamed “The Peerless Leader” because he was a team leader on the Cubs who later became a manager. He was nicknamed “Husk” because he was big (six feet), husky, and took no guff from players—or managers, or fans, or anyone, for that matter.

Chance began his career as a catcher, but when Johnny Kling came along he was moved to first base. He was fast for a first baseman: In 1903 he stole 67 bases to lead the league, and in 1906, swiped a league-best 57.

His best years were from 1903 to 1908. He hit .300 or better four years in a row, from 1903 to 1906; stole between 27 and 67 bases each year; and led the National League in runs scored in 1906. In 1907, Chance led all National League first basemen in fielding percentage.

He was a clutch player. He batted .421 in the 1908 World Series against the Tigers, with five stolen bases and four runs scored. In that tumultuous 1908 season, Chance made what may still be considered the biggest hit in franchise history: a bases-loaded double that scored three runs that defeated the Giants and propelled Chicago to the World Series.

Chance took over the managerial reins of the Cubs in 1905, and by 1908, began to play less and less. He hit .298 in 1910, which was the last season he was a semi-regular.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .296, HR: 20, RBI: 596, H: 1,273, SB: 401

#165 Louis “Lou” Boudreau

SS-3B-1B, Indians, Red Sox, 1938–52. Hall of Fame, 1970

Boudreau came up with the Indians in 1938, and played sparingly. But by 1940, he was the team’s starting shortstop, hitting .295, with 46 doubles, 10 triples and 101 RBI. He made the All Star team and also led American League shortstops in fielding percentage.

By 1942, Boudreau was, at 24, the team leader. He also became the team manager, the youngest man ever to take charge of a team at the onset of a season.

Boudreau was a hustler who took full advantage of his limited gifts. Never afraid to take the extra base, he led the league in doubles three times. A smart player in the field who studied hitters, he led the league in fielding percentage by a shortstop eight times. In 1944, he won the batting title with a .327 average.

In 1948, Boudreau had an amazing season: He hit .355, second best in the league, with 199 hits, 106 RBI, 34 doubles, 18 home runs and 98 walks. He struck out only nine times all year. That season, the Indians and Red Sox tied for first place in the American League, Boudreau went four-for-four with two homers to lead the Indians to the championship.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 68, RBI: 789, H: 1,779, SB: 51

#166 Darrell Wayne Evans

3B-1B-DH, Braves, Giants, Tigers, 1969–89

The power-hitting Evans was one of the best third basemen of his era, and was the first player to hit 40 home runs in both leagues.

Evans came up with Atlanta in 1969, becoming the Braves’ regular third baseman by the 1971 season. That was the season he first wore contact lenses, and Evans credits that adjustment with helping him improve.

By 1973, he was an All Star, hitting .281 with 41 homers, 104 RBI and a league-leading 124 walks. He and teammates Henry Aaron (40) and Davey Johnson (43) became the first teammates to hit 40 or more home runs in the same season.

Evans usually batted third, ahead of Aaron, and was on first base on April 8, 1974, the day Aaron belted home run Number 715 to break Babe Ruth’s record. A patient hitter, Evans led the league in walks twice and five times had 100 or more.

He was traded to Detroit in 1984, and led the league in home runs with 40 the following year, his only home run crown. But he was one of the cornerstones of the Tigers’ World Championship team of 1984.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .248, HR: 414, RBI: 1,354, H: 2,223, SB: 98

#167 Alexander Emmanuel “A-Rod” Rodriguez

SS-3B-DH, Mariners, Rangers, Yankees, 1994–2016

The complicated legacy of Alex Rodriguez starts with the fact that he is undoubtedly a great player. He was one of the top players in the majors two years after he broke into the league in 1994. By 1996, at age 20, he won the batting championship with a .358 average, to go with 36 home runs, 123 RBI and a league-best 54 doubles and 141 runs scored. From 2001 to 2003, Rodriguez led the American League in home runs. In 2003, he was league MVP, hitting .298 with 47 homers and 118 RBI. He also won his second Gold Glove. In 2004, Rodriguez was traded from Texas to the Yankees, and helped New York win the World Series in 2009. But he had a long history of using performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs). It is a situation that dogged his career.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .295, HR: 696, RBI: 2,086, H: 3,115, SB: 329

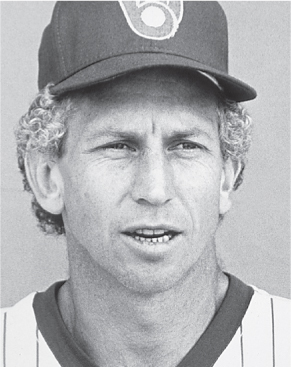

#168 Salvatore Leonard “Sal” Bando

3B-DH, Athletics, Brewers, 1966–80

Bando was a power-hitting third baseman who was the team leader of the raucous, three-time World Champion Oakland Athletics.

Bando’s stats were rarely overpowering. In fact, a look at his postseason numbers would lead the unsuspecting observer to think he had played poorly: Bando hit only .206 in three World Series, and .270 in five League Championship Series.

So much for stats. Bando knocked in the tying run in Game Seven of the 1972 World Series against the Reds and then scored the game-winner in a 3–2 win. In Game Two of the 1973 American League Championship Series, he belted two home runs to help the A’s win the game and tie the series.

And in Game Four of the 1974 ALCS, Bando’s solo shot in Game Three was the only run of the game. Bando scored the game-winning run the next day to close out the Orioles.

His regular season numbers were similar. Bando did lead the league in doubles in 1973 with 32, but that is really the only major statistical category he ever won. He was consistent, however. Bando hit 20 or more home runs six times in his career, 20 or more doubles 10 times and twice had over 100 RBI.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .254, HR: 242, RBI: 1,039, H: 1,790, SB: 75

#169 Hilton Lee Smith

RHP-OF, Monroe Monarchs, New Orleans Crescent Stars, Kansas City Monarchs (Negro Leagues), 1932–48. Hall of Fame, 2001

Smith was known, for many years in the Negro Leagues, as “Satchel Paige’s relief,” as Smith would inevitably come in for Paige after Paige had made an appearance and pitched for three innings. Smith would come in and finish the game.

There were many players, both teammates and opponents, who declared that Smith might have been a better pitcher than Paige. But Smith was as low-key as Paige was loquacious, and that demeanor worked against him.

Smith did have the uncanny control that Paige had, but he had an excellent curveball and a live fastball that hopped as it reached the plate. Smith also threw both sidearm and overhand, which further befuddled batters.

Smith played for several teams in the south before signing with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1936. He would remain one of the aces of the Monarch staff for years to come.

Smith led the Negro American League in strikeouts in 1938, 1939, 1940 and was second in 1941. Smith pitched in six consecutive Negro League All Star games, and his 13 strikeouts in those contests are second all-time.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 78, L: 28

#170 Atanasio “Tony,” “Doggie” Perez

1B-3B-DH, Reds, Expos, Red Sox, Phillies, 1964–86. Hall of Fame, 2000

Perez was an RBI machine for most of his career. He only hit .300 or better three times in a 23-year career, but drove in 90 or more runs 12 times.

Perez was a first baseman for his initial three years with the Reds, from 1964 to 1966. He was moved over to third base from 1967 to 1971, to make room for Lee May. But he was moved back to first in 1972, where he remained for most of the rest of his career.

Perez was one of the cornerstones of the “Big Red Machine” of the 1970s. His job was to drive in runs, and nobody did it better in that span. He hit 20 or more home runs nine times, and his RBI totals from 1967 to 1976 never fell below 90.

Perez was a pretty good fielder, as well, leading National League first baseman in fielding percentage in 1974 with a .996 mark.

In the postseason, Perez usually shone, even if his numbers weren’t always outstanding. He hit only .179 against the Red Sox in 1975, for example, but three of his five hits in the series were home runs, including a solo blast in Game Seven. He had 10 hits in the 1972 series loss to Oakland.

Following the 1976 season, Perez wandered around the big leagues, spending three years each in Montreal and Boston, and a year in Philadelphia before returning to Cincinnati to retire.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .279, HR: 379, RBI: 1,652, H: 2,732, SB: 49

#171 Graig “Puff” Nettles

3B-OF, Twins, Indians, Yankees, Padres, Braves, Expos, 1967–88

Nettles was an acrobatic, power-hitting third baseman who showcased his talent with the New York Yankees from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s.

Nettles started out as an outfielder for the Twins at the beginning of his career, but by the time he got to Cleveland, he was manning third. Nettles proved how wise that move was by leading the league’s third basemen in fielding percentage. In 1971, he set an American League record with 412 assists and 54 double plays.

He was traded to the Yankees at the start of the 1973 season, and had problems adapting. His average fell to .234 and he fielded poorly. But he rebounded over the next few seasons, and was named to the All Star team in 1975.

Nettles was one of the leaders of the Yankees’ three consecutive American League champions from 1976 to 1978. He led the league in home runs with 32 in 1976, and won Gold Gloves in 1977 and 1978.

His defensive play in 1977 was amazing. In Game Three of the World Series, Nettles made three diving stops of line drives that preserved a 5–1 Yankee win over the Dodgers. Los Angeles coach Tommy Lasorda said later that Nettles’s defensive play that night was the greatest individual effort he had ever seen.

Nettles’s production dropped off in the early 1980s, and he was traded to the Padres. But there, at age 40, he and ex-teammate Goose Gossage helped San Diego to the National League pennant.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .248, HR: 390, RBI: 1,314, H: 2,225, SB: 32

#172 Anthony Michael “Poosh ’Em Up” Lazzeri

2B-3B, Yankees, Cubs, Dodgers, Giants, 1926–39. Hall of Fame, 1991

Lazzeri was part of the Yankees’ “San Francisco connection” of the 1920s and 1930s, ballplayers like Lazzeri, Frankie Crosetti and Joe DiMaggio who were weaned in the ballyards of the City by the Bay.

Lazzeri came to the Yankees in 1926 and immediately took over the second base chores. He hit .275 and drove in 114 runs that year. The next year, Lazzeri hit .309 and drove in 102 runs.

He was painfully shy, and an epileptic. Lazzeri never had a seizure on the field, but teammates recall that he would have one or two during the season. Roommate Mark Koenig carried a roll of pencils with him at all times, to shove between Lazzeri’s jaws to prevent him from swallowing his tongue.

A fan favorite, Lazzeri’s nickname came from his Italian countrymen urging Lazzeri to “Poosh ’Em Up!” or hit a home run, when he came to bat.

Playing with offensive powerhouses like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Lazzeri never led the league in any of the power categories. But he drove in 100 or more runs seven times, hit 10 or more homers 10 times and hit .300 or more five times. He became the first major leaguer to hit two grand slams in one game, in 1936, setting an AL single-game record with 11 RBI.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .292, HR: 178, RBI: 1,191, H: 1,840, SB: 148

#173 Gaylord Jackson Perry

RHP, Giants, Indians, Rangers, Padres, Yankees, Braves, Mariners, Royals, 1962–83. Hall of Fame, 1991

The (alleged) master of the spitball, and various other illegal pitches, Perry was the first player to win the Cy Young award in both leagues.

Perry was signed by the Giants, and spent four unremarkable seasons there as a spot starter. In 1966, Perry got off to an amazing start, at one point owning a 20–2 record, before tailing off to a very solid 21–8 mark. Still, he earned a berth in the All Star game, the first of five.

Perry won 20 or more games twice with the Giants, but slumped to 16–12 in 1971, and was traded to the Indians. But in 1972, Perry led the league with 24 wins, five shutouts and 342 2/3 innings pitched. It was good enough to win his first Cy Young award. After a stint with the Texas Rangers, Perry was traded again, this time to the San Diego Padres.

Perry had a masterful first season with San Diego, going 21–6, with a 2.73 ERA, 154 strikeouts and 260 2/3 innings pitched. He easily won his second Cy Young that year.

Perry had an assortment of pitches, including a good curve and a live slider. But over the years, allegations surfaced that he also doctored the ball, using spit, or Vaseline, or grease or something.

Perry was constantly moving on the mound, touching his cap, his uniform, his hair, and was often searched by umpires, who never found anything. All those shenanigans were, more often than not, used by Perry to distract the batter.

LIFETIME STATS: W: 314, L: 265, SV: 11, ERA: 3.11, SO: 3,534, CG: 303

#174 Sherwood Robert “Sherry” Magee

OF-1B, Phillies, Braves, Reds, 1904–19

Magee was a feared slugger at the turn of the 20th century, several times leading his league in RBI. But more than that, he was an excellent all-around ballplayer who could also run and field exceptionally well.

Magee spent his rookie year with the Philadelphia Phillies on the bench, for the most part. The next year, however, he got his chance, and made the most of it, hitting .299, scoring 100 runs and driving in 98. Two years later, he hit .328, with 28 doubles and a league-best 85 RBI.

In 1910, Magee won his only batting title with a .331 average, and also topped the league with 123 RBI, 110 runs scored, a .445 on-base percentage and a .507 slugging percentage.

Magee did not suffer fools well. He was critical of teammates who made mental errors, and was once suspended for five weeks after punching an umpire who Magee thought was doing a sloppy job.

He was an excellent fielder, leading the league’s outfielders in fielding percentage in 1911. He was also an excellent base-stealer. Magee stole home 23 times in his career and seven times stole 30 or more bases in a season. On July 12, 1906, he stole second base, third base and home against St. Louis.

LIFETIME STATS: BA: .291, HR: 83, RBI: 1,176, H: 2,169, SB: 441

#175 Maurice Morning “Maury” Wills

SS-3B, Dodgers, Pirates, Expos, 1959–72

Wills was actually a pretty decent hitter who was also a pretty good infielder, but he is most remembered for his phenomenal success in stealing bases in the early 1960s.