Stood alongside Chris Boardman after winning the junior Grand Prix des Nations at 18 years old. One of eleven wins I took in my first year in France.

Stood alongside Chris Boardman after winning the junior Grand Prix des Nations at 18 years old. One of eleven wins I took in my first year in France.

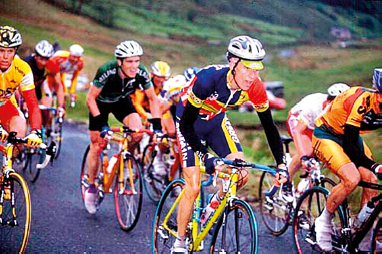

I needed them and they needed me. Racing for the Great Britain team as an Under-23, at the World Championships at Valkenburg in 1998 (above) and in the PruTour of Great Britain in 1999 (below), aged 20 and 21 respectively.

Mapei was a team and an organisation that was ahead of its time. Their approach was cutting edge but more than anything they wanted the best for the sport.

Tour of Denmark 2000. Mapei may have been the super team at the time, but changing, washing and basic medical attention was still done out of the back of a car. How times change.

Riders like Andrea Noe (right) took it upon themselves to teach me the only job that they knew: that of the domestique.

By the time I returned to the GB team for the 2000 World Road Race Championships I already felt like a stranger in a team that I had been an integral part of only twelve months earlier.

If Mapei had been DHL then De Nardi was the Post Office. Everything worked, and we had nothing to complain about, but everything was stripped down to the absolute bare minimum.

I started my first Giro a little over seven months after my first Vuelta, and things couldn’t have been more different. Unlike in Spain, where I had solely been surviving, in Italy I was able to be a part of the racing.

Riding on the front of the Maglia Rosa group on the Mortirolo in the 2004 Giro. It was the moment I had waited my entire career for. All the other things that I felt complicated racing for me disappeared: I could just ride.

Tom Southam leads the peloton at the 2005 World Championships, where I made a mistake that would impact both our careers.

Representing Great Britain at the Athens Olympics in 2004 should have been a big moment for me, instead the whole thing felt like more of a tourist trip.

Stefano Zanini, or ‘Zaza’, was like a big brother to me in Italy. He always knew when I needed some advice, an invitation to dinner, or, on one occasion, throwing against a wall for a stern talking to.

At Liquigas I finally felt at home. There I found myself riding alongside riders like Dario Cioni who respected me, and knew how to get the best out of me.

I enjoyed the best years of my career at Liquigas, but despite being close to victory on several occasions myself I never once held any personal ambition beyond doing the best job I could for the team.

The Grand Départ of the 2007 Tour de France in London. My Italian teammates were less than impressed by the hotel food, asking me, ‘Does the Queen have to eat beans in tomato sauce for breakfast?’

Working for Danilo Di Luca at the 2005 Giro. A real domestique becomes invaluable when he is the only rider left in the front who is riding for someone else and not to win himself.

Starting a wet Tour time trial on stage 13 of the 2007 race. That TT was tough, but I was about to experience another hazard of cycling the Tour – staying in the worst hotels known to man.

Liquigas made the very most of my talents, they knew exactly when and how to use me as a rider. Leaving them at the end of 2008 would prove to be a costly mistake.

At the 2009 Tour de France. On the outside I had become the rider that I had always wanted to be, but my professional cyclist’s exterior hid an inner turmoil that was making me ask questions of myself, and my profession.

Descending in the 2009 Tour. Once Cadel lost hope of a high overall finish the team that had been built around him became a sinking ship.

Cadel Evans’s intensity ran me ragged in the first week of the 2009 Tour, and left me with nothing for the mountain stages where he needed me.

The race I couldn’t finish – the Omega Pharma-Lotto team celebrate without me on the Champs Elysee at the end of the 2010 Tour de France. It was an image and a world I knew that I no longer wanted to be a part of.

Happy at home. With my wife Camilla, our son Emil and my mother Jane in Janakkala, Finland, 2012.