1

I Hate Me

The Rise and Decline of the Human Body

Zoe seemed to have everything going for her. A brilliant, high-achieving homeschool student, she was offered a full ride by two Ivy League universities when she was only seventeen years old and a junior in high school.

Then, without any warning, Zoe ran away from home.

Frantic with fear and grief, her parents learned that she had been seduced by a twenty-two-year-old college senior—we’ll call her Holly—who attended a nearby evangelical Christian university. They had met at a Christian homeschool organization where Holly was teaching. Because the age of consent in the state where they lived is eighteen, their relationship was illegal. Worried about a possible lawsuit, Holly persuaded Zoe to run away to another state with a lower age of consent.

Though Zoe’s parents chose not to press charges, sexual assault laws that might have applied include statutory rape, enticement of a minor for sexual activity, abduction of a minor, and sexual assault of a child by a school staff person or a person who works or volunteers with children. (In the law, “child” means a minor.)

To garner sympathy (and get government benefits), Zoe claimed that her parents had kicked her out of the house. Many family friends believed her, with the result that her parents were cut off by friends in addition to the heartache of losing their daughter.

Within months of persuading Zoe to move with her across the country, Holly dropped her to engage in affairs with other women. Today Holly is completing her doctoral degree at a prestigious Ivy League university, studying gender and sexual orientation. Zoe is waiting on tables at a coffee shop—confused and depressed. A victim of the sexual revolution.1

In our day, issues of life and sexuality are not merely theoretical; they affect virtually everyone in a personal way. To respond effectively to today’s secular moral revolution, we must dig down to the underlying worldview that drives it. In the introduction, we learned that the worldview supporting secular morality is a profoundly fragmenting dualism that separates body and person. If you get a handle on this two-story division, you will have the tools to uncover the deeply dehumanizing worldview at the heart of abortion, assisted suicide, homosexuality, transgenderism, and the sexual chaos of the hookup culture.

In this chapter, I map out the two-story worldview through an overview of the most salient moral issues. Then, in later chapters, I will unpack each one in greater detail and answer the most common objections. By contrast with the secular worldview, it will become clear that a biblical ethic affirms a full-orbed, wholistic view of the person that supports human rights and dignity.

Being Human Is Not Enough

The best way to grasp the body/person dichotomy is through an example. A few years ago, an article appeared by a British broadcaster named Miranda Sawyer, who described herself as a liberal feminist. In the article she said she had always been firmly pro-choice.

Until she became pregnant with her own baby.

Then she began to struggle. “I was calling the life inside me a baby because I wanted it. Yet if I hadn’t, I would think of it just as a group of cells that it was OK to kill. . . . That seemed irrational to me. Maybe even immoral.”2 Babies in the womb don’t qualify as human only if someone wants them.

Sawyer had run up against the wall of reality—and reality did not fit her ideology. So she began researching the subject, and even produced a documentary. Finally she reached her conclusion: “In the end, I have to agree that life begins at conception. So yes, abortion is ending that life.” Then she added, “But perhaps the fact of life isn’t what is important. It’s whether that life has grown enough . . . to start becoming a person.”3

What has happened here to the concept of the human being? It has been torn in two. If a baby is human life from conception but not a person until some later time, then clearly these are two different things.

This is a radically fragmented, fractured, dualistic view of the human being.

In ordinary conversation, of course, we use the phrase human being to mean the same thing as person. The two terms were ripped apart by the Supreme Court in its 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion decision, which ruled that even though the baby in the womb is human, it is not a person under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Thus we have a new category of individual: the human non-person.

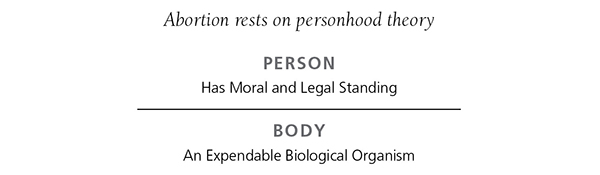

To picture this modern dualism, we can apply Schaeffer’s image of two stories in a building (see introduction). In the early stages the fetus is in the lower story. Here it is acknowledged to be human from conception, in the sense that it is a biological organism knowable by the empirical methods of science. But it is not thought to have any moral standing, nor does it warrant legal protection. Later, at some undefined point in time, it jumps into the upper story and becomes a person, typically defined in terms of a certain level of cognitive functioning, consciousness, and self-awareness. Only then does it attain moral and legal standing.

This is called personhood theory, and it is an outworking of the fact/value split: To be biologically human is a scientific fact. But to be a person is an ethical concept, defined by what we value.

The implication of this two-story view is that simply being human is not enough to qualify for rights. Recall Sawyer’s words: “The fact of life isn’t what is important.” Human life in itself is thought to have no value, and what we do with it has no moral significance.

Of course, an individual making a decision about abortion may not be consciously thinking about these philosophical implications. Some people have told me they can support abortion and still feel that the baby has value. But an action can have a logic of its own, whether we intend it or not.

If you favor abortion, you are implicitly saying that in the early stages of life, an unborn baby has so little value that it can be killed for any reason—or no reason—without any moral consequence. Whatever your feelings, that is a very low view of life. Then, by sheer logic, you must say that at some later time the baby becomes a person, at which point it acquires such high value that killing it would be a crime.

The implication is that as long as the pre-born child is deemed to be human but not a person, it is just a disposable piece of matter—a natural resource like timber or corn. It can be used for research and experiments, tinkered with genetically, harvested for organs, and then disposed of with the other medical waste.

The assumption at the heart of abortion, then, is personhood theory, with its two-tiered view of the human being—one that sees no value in the living human body but places all our worth in the mind or consciousness.4

Personhood theory thus presumes a very low view of the human body, which ultimately dehumanizes all of us. For if our bodies do not have inherent value, then a key part of our identity is devalued. What we will discover is that this same body/person dichotomy, with its denigration of the body, is the unspoken assumption driving secular views on euthanasia, sexuality, homosexuality, transgenderism, and a host of related ethical issues.

“Reading” Nature

To understand this two-story dualism, we need to ask where it came from and how it developed. To begin with, what does the word dualism mean? On the one hand, it is simply the claim that reality consists of two kinds of substances instead of only one. In that traditional sense, Christianity is dualistic because it holds that there exists both body and soul, matter and spirit. These two substances causally interact with one another, but neither one can be reduced to the other. The reality of the spiritual realm is important to defend today because the academic world is dominated by the philosophy of materialism (the claim that nothing exists beyond the material world).5

Yet Christianity holds that body and soul together form an integrated unity—that the human being is an embodied soul (as we will see in more detail at the end of this chapter). By contrast, personhood theory entails a two-level dualism that sets the body against the person, as though they were two separate things merely stuck together. As a result, it demeans the body as extrinsic to the person—something inferior that can be used for purely pragmatic purposes.

How did such a negative view of the body develop?

Because the body is part of nature, the answer lies in the way people have thought about nature. For centuries, Western culture was permeated by a Christian heritage that regards nature as God’s handiwork, reflecting his purposes. As the church fathers put it, God’s revelation comes to us in “two books”—the book of God’s Word (the Bible) and the book of God’s world (creation).6 Nature is an expression of God’s purposes and a revelation of his character. The psalmist writes, “The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands” (Ps. 19:1). In Romans, the apostle Paul says creation gives evidence for God: “Since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made” (Rom. 1:20).

In other words, even though the world is fallen and broken by sin, it still speaks of its Creator. We can “read” signs of God’s existence and purposes in creation. This is called a teleological view of nature, from the Greek word telos, which means purpose or goal. It is evident that living things are structured for a purpose: Eyes are for seeing, ears are for hearing, fins are for swimming, and wings are for flying. Each part of an organ is exquisitely adapted to the others, and all interact in a coordinated, goal-directed fashion to achieve the purpose of the whole. This kind of integrated structure is the hallmark of design—plan, will, intention.

Even today, biologists cannot avoid the language of teleology, though they often substitute phrases like “good engineering design.”7 Scientists say an eye is a good eye when it is fulfilling its purpose. A wing is a good wing when it is functioning the way it was intended.

Yet the most impressive examples of engineering have become visible only with the invention of the electron microscope. Each of the nanomachines within the cell (such as proteins) has its own distinctive function. Researchers conduct experiments they describe as “reverse engineering,” as though they had a gadget in hand and were trying to reconstruct the process by which it was designed.

The smoking gun for design, however, is in the cell’s nucleus—its command and control center. The DNA molecule stores an immense amount of information. Geneticists talk about DNA as a “database” that stores “libraries” of genetic information. They analyze the way RNA “translates” the four-letter language of the nucleotides into the twenty-letter language of proteins. The search for the origin of life has been reframed as the search for the origin of biological information.

And information implies the existence of a mind—an agent capable of intention, will, plan, or purpose. The latest scientific evidence suggests that the New Testament has it right: “In the beginning was the Word” (John 1:1). In the original Greek, the term translated as “Word” is logos, which also means reason, intelligence, or information.

Scientists have discovered evidence for teleology not only in living things, however, but also in the physical universe. They have found that its fundamental physical constants are exquisitely coordinated to support life. Harvard astrophysicist Howard Smith writes, “The laws of the universe include fundamental numbers like the strengths of the four forces, the speed of light, Planck’s constant, the masses of electrons or protons, and others. . . . If those values were slightly different, even by a few percent, we would not be here. . . . Life, much less intelligent life, could not exist.”

This is called the fine-tuning problem, and what it means is that even the physical world exhibits the hallmark of design. The subtitle of Smith’s article states, “Almost in spite of themselves, scientists are driven to a teleological view of the cosmos.”8

If nature is teleological, and the human body is part of nature, then it is likewise teleological. It has a built-in purpose, part of which is expressed as the moral law. We are morally obligated to treat people in a way that helps them fulfill their purpose. This explains why biblical morality is not arbitrary. Morality is the guidebook to fulfilling God’s original purpose for humanity, the instruction manual for becoming the kind of person God intends us to be, the road map for reaching the human telos. This is sometimes called natural law ethics because it tells us how to fulfill our true nature, how to become fully human.

In this purpose-driven view, there is no dichotomy between body and person. The two together form an integrated psycho-physical unity. We respect and honor our bodies as part of the revelation of God’s purpose for our lives. It is part of the created order that is “declaring the glory of God.”

The implication is that the physical structure of our bodies reveals clues to our personal identity. The way our bodies function provides rational grounds for our moral decisions. That’s why, as we will see, a Christian ethic always takes into account the facts of biology, whether addressing abortion (the scientific facts about when life begins) or sexuality (the facts about sexual differentiation and reproduction). A Christian ethic respects the teleology of nature and the body.

Matter without Meaning

What changed this purpose-driven view of nature? How did the West lose its positive view of the body?

In the modern age, the most important turning point was Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, published in 1859. (There were others before him, as we will see, but Darwin has the greatest impact today.) Darwin could not deny that nature appears to be designed. But having embraced the philosophy of materialism, he wanted to reduce that appearance to an illusion. He hoped to show that although living structures seem to be teleological, in reality they are the result of blind, undirected forces. Although they seem to be products of intention (will, plan, intelligence), in reality they are products of a purposeless material process. The two main elements in his theory—random variations and natural selection—were both proposed expressly to eliminate plan or purpose.

As historian Jacques Barzun notes, “This denial of purpose is Darwin’s distinctive contention.”9 Zoologist Richard Dawkins agrees: “Natural selection, the blind, unconscious automatic process which Darwin discovered . . . has no purpose in mind.”10

On a Richter scale of thinkers, Darwin’s theory caused an earthquake that ranks well above 9.0. And its seismic waves were not limited to science. It also caused severe aftershocks in moral thought. For if nature was not the handiwork of God—if it no longer bore signs of God’s good purposes—then it no longer provided a basis for moral truths. It was just a machine, churning along by blind, material forces. Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor explains, “The cosmos is no longer seen as the embodiment of meaningful order which can define the good for us.”11

The next step in the logic is crucial: If nature does not reveal God’s will, then it is a morally neutral realm where humans may impose their will. There is nothing in nature that humans are morally obligated to respect. Nature becomes the realm of value-neutral facts, available to serve whatever values humans may choose.

And because the human body is part of nature, it too is demoted to the level of an amoral mechanism, subject to the will of the autonomous self. If the body has no intrinsic purpose, built in by God, then all that matters are human purposes. The body is reduced to a clump of matter—a collection of atoms and molecules, not essentially different from any other chance configuration of matter. It is raw material to be manipulated and controlled to serve the human agenda, like any other natural resource.12

We tend to think of materialism as a philosophy that places high value on the material world, because it claims that matter is all that exists. Yet, ironically, in reality it places a low value on the material world as purely particles in motion with no higher purpose or meaning.

Disposable Humans

Do you see how this explains the logic undergirding abortion? In the past, abortion advocates typically denied that a pre-born baby is human: It’s just a blob of tissue—a potential life—a collection of cells. As a consequence, many pro-life arguments focused on proving that a fetus is human life. Today, however, due to advances in genetics and DNA, virtually all professional bioethicists agree that life begins at conception. An embryo has a full set of chromosomes and DNA. It is a complete and integral individual capable of internally directed development in a seamless continuum from fertilization.

Why isn’t this taken as conclusive evidence that abortion is morally wrong? Because according to personhood theory, when talking about the human as a biological organism we are in the realm of science (the lower story) where life has been reduced to a mere mechanism with no intrinsic purpose or dignity. It has been devalued to raw material that may be deployed for whatever pragmatic benefits we get from it. As a result, even bioethicists who recognize the fetus as biologically human do not necessarily conclude it has moral standing or should be legally protected. Instead the fetus is treated as just a piece of matter, which can be used for research or experiments, then tossed out with the other medical garbage.

In the two-story worldview, simply being a member of the human race is not enough to qualify for personhood. The baby in the womb has to earn the status of personhood by achieving a certain level of cognitive functioning—the capacity for consciousness, self-awareness, autonomy, and so on.

Personhood theory is the assumption behind most common arguments for abortion. For example, when John Kerry was running for US president in 2004, he surprised the public by agreeing that “life begins at conception.” In that case, how could he support abortion? Because, as he explained in an interview with broadcaster Peter Jennings, the pre-born baby is “not the form of life that takes personhood in the terms that we have judged it to be.”13

Bioethicists who adopt personhood theory often claim to be scientific, yet the theory has no scientific support. Clearly, it would take a dramatic transformation to turn a mere human organism with no rights into a person with an inviolable right to life. But there is no scientific evidence of such a transformation—no single, dramatic turning point that can be empirically detected. Embryonic development is a continuous process, gradually unfolding the potentials that were built in from the beginning. The two-story concept of personhood is neither empirical nor scientific.

The scientific evidence actually favors a teleological view, which sees the human being as a coherent whole from conception. In a Christian worldview, everyone who is human is also a person. The two cannot be separated. This view avoids the radical devaluation of human life. From its earliest stages, the body participates in the human telos, and thus shares in the purpose and dignity of the human person. (We will explore abortion more fully and answer objections in chapter 2.)

Dr. Humane Death

What about euthanasia? How does it express the two-story divided worldview? Many Americans still recall the 2005 Terri Schiavo case. Terri was a young married woman who suffered cardiac arrest and was declared by some doctors to be in a persistent vegetative state. Her husband wanted to discontinue her food and water. But her biological family, who took care of her, disputed the diagnosis. They lined up medical experts who claimed that Terri responded to efforts to communicate. After a series of highly publicized court cases, and even the intervention of the US Congress, her food and water were cut off, leading to her slow death by dehydration and starvation.

Terri’s story was presented in the media as a right-to-die case. But Terri was not dying. She was not terminally ill. So that was not actually the heart of the debate. The core issue was personhood theory. In a television debate, Wesley Smith of the Discovery Institute asked a bioethicist from the University of Florida, “Do you think Terri is a person?”

“No, I do not,” the bioethicist replied. “I think having awareness is an essential criterion of personhood.”14

Whatever you think of the politics surrounding Terri’s case, that interchange captures its worldview significance. According to personhood theory, if you are mentally disabled, if you no longer have an arbitrarily prescribed level of neocortical functioning, then you are no longer a person—even though you are obviously still human.

Those who argued in favor of cutting off Terri’s food and water included a neurologist named Ronald Cranford, who styles himself “Dr. Humane Death.” Cranford has a reputation for promoting euthanasia even for disabled people who are conscious and partly mobile. In a California case, a man named Robert Wendland was brain-damaged in a car accident. He was able to perform logical tests with colored pegs, press buttons to answer yes-and-no questions, and even scoot along hospital hallways in an electric wheelchair (like the famous physicist Stephen Hawking). Yet Cranford argued in court that Wendland was not a person and that his food and water should be cut off.15

According to the body/person dichotomy, just being biologically part of the human race (the lower story) is not morally relevant. Individuals must earn the status of personhood by meeting an additional set of criteria—the ability to make decisions, exercise self-awareness, plan for the future, and so on (the upper story). Only those who meet these added conditions qualify as persons.

Those who do not make the grade are demoted to non-persons. And a non-person is just a body—a disposable piece of matter, a natural resource that can be used for research or harvesting organs or other purely utilitarian purposes, subject only to a cost-benefit analysis.

Just as with abortion, we are talking about the logic implied by the act itself, no matter how an individual feels about it. You may intend to be compassionate by ending the life of a suffering patient. But your actions imply a two-story worldview that is dehumanizing—one in which humans do not have rights, only persons do. The only way to stand against the culture of death is to accept that all humans are also persons. No one is excluded. (We will explore euthanasia and assisted suicide more deeply in chapter 3.)

Hooking Up, Splitting Apart

What about sexuality? Surprisingly, the secular view on sexuality exhibits the same body/person dualism.

In the two-story worldview, if the body is separate from the person, as we saw in abortion and euthanasia, then what you do with your body sexually need not have any connection to who you are as a whole person. Sex can be purely physical, separate from love.

Our sexualized culture actually encourages people to keep the two separate. Seventeen magazine warns teen girls to “keep your hearts under wraps” or boys may find you “boring and clingy.” Cosmo advises women that the way to “wow a man after sex” is to ask for a ride home. (Make it clear you have no intention of hanging around hoping for a relationship.)

These examples were collected by Wendy Shalit in her book Girls Gone Mild.16 On her website, Shalit posts letters from readers, some of them heartrending. The day I checked the site, there was a letter from sixteen-year-old Amanda lamenting that in a typical high school, “the more detached you can be from your sexuality, the cooler you are.” She added that even adults—teachers, books, magazines, parents—often urge teens to adopt a No Big Deal attitude toward sexuality.

As though to prove the point, reviews of Shalit’s book actually defended loveless physical encounters. The Washington Post suggested that it is healthy when teenage girls “refuse to conflate” love and sex: “Sometimes they coexist, sometimes not.” The Nation asked defiantly, “Why should sex have an everlasting warranty of love attached to it?”17 Why indeed, if the body is just a piece of matter that can be stimulated for pleasure with no meaning for the whole person?

The same bleak view of sexuality is inculcated in even young children. A video put out by Children’s Television Workshop, widely used in sex education classes, defines sexual relations as simply “something done by two adults to give each other pleasure.”18 No mention of marriage or family—or even love or commitment. No hint that sex has a richer purpose than sheer sensual gratification.

This is sex cut off from the whole person—sex as an exchange of physical services between autonomous, disconnected individuals. We tend to think sexual hedonism places too much value on the purely physical dimension. But in reality it places a very low value on the body, draining it of moral and personal significance.

In the hookup culture, partners are referred to as “friends with benefits.” But that is a euphemism because they are not really even friends. The unwritten etiquette is that you never meet just to talk or spend time together. A New York Times article explains, “You just keep it purely sexual, and that way people don’t have mixed expectations, and no one gets hurt.”19

Except when they do. The same article features a teenager named Melissa who was depressed because her hookup partner had just “broken up” with her. No matter what the current secular philosophy tells them, people cannot disassociate their emotions from what they do with their bodies.

In the biblical worldview, sexuality is integrated into the total person. The most complete and intimate physical union is meant to express the most complete and intimate personal union of marriage. Biblical morality is teleological: The purpose of sex is to express the one-flesh covenant bond of marriage.

The loving way to treat young people is not to hand out contraceptives, which amounts to collusion in impersonal and ultimately unfulfilling sexual encounters. Far more loving is to inspire them with a higher view of sexuality. In reconnecting body and person, they can experience a deep sense of healing and personal integration. (We will delve more deeply into sexuality in chapter 4.)

Same Sex in Conflict

What about homosexuality? Even in churches, young people often do not understand why the Bible teaches that same-sex relations are morally wrong. It makes more sense when we realize that a secular approach rests on the same divided view of the human being, with its devaluing of the body.

Most people assume that same-sex desire is genetically based. Certainly we do not choose our sexual attractions. They come to us involuntarily and feel natural. Yet despite intensive research, scientists have not turned up clear evidence of a genetic cause.

What studies do show is that sexual desires have physical correlates. For example, when scientists use magnetic resonance imaging (MRIs), they find that some men’s brains light up in response to female images, while others’ light up in response to male images. But people’s brains also light up in response to fear, love, and even religious experiences. This should not be surprising. Humans are unified beings. Knowing that feelings have physical correlates can help us be more compassionate toward people. But it does not tell us what is right or wrong, moral or immoral.

Whatever the cause of homoerotic inclinations, when we act on them we implicitly accept the two-story divide. Think of it this way: Biologically, physiologically, chromosomally, and anatomically, males and females are counterparts to one another. That’s how the human sexual and reproductive system is designed. Anglican theologian Oliver O’Donovan writes, “To have a male body is to have a body structurally ordered to loving union with a female body, and vice versa.”20 The body has a built-in telos, or purpose.

To engage in same-sex behavior, then, is implicitly to say: Why should my body inform my psychological identity? Why should the structural order of my body have anything to say about what I do sexually? Why should my moral choices be directed by its telos? The implication is that what counts is not my sexed body (lower story) but solely my mind, feelings, and desires (upper story). The assumption is that the body gives no clue to our identity; it gives no guidance to what our sexual choices should be; it is irrelevant and insignificant.

This is a profoundly disrespectful view of the human body.

Every practice comes with a worldview attached to it—one that many of us might not find true or attractive if we were aware of it. Therefore it is important to become aware. Same-sex behavior has a logic of its own, apart from what we subjectively feel or intend. The person who adopts a same-sex identity must disassociate their sexual feelings from their biological identity as male or female—implicitly accepting a two-story dualism that demeans the human body. Thus it has a fragmenting, self-alienating effect on the human personality.

By contrast, biblical morality expresses a high view of the dignity and significance of the body. The biblical view of sexuality is not based on a few scattered Bible verses. It is based on a teleological worldview that encourages us to live in accord with the physical design of our bodies. By respecting the body, the biblical ethic overcomes the dichotomy separating body from person. It heals self-alienation and creates integrity and wholeness. The root of the word integrity means whole, integrated, unified—our mind and emotions in tune with our physical body. The biblical view leads to a wholistic integration of personality. It fits who we really are. (We will walk through several real-life examples and answer objections to the biblical view in chapters 5 and 6.)

“I Am Not My Body”

Many people find it easier to recognize the denigration of the body in arguments supporting transsexualism or transgenderism. Transgender people often say they are trapped in the “wrong body.”

This sense of a mismatch between physical sex and psychological gender is called gender dysphoria. Most people assume that it must have some biochemical basis, perhaps a hormonal cause. To date, however, no clear scientific evidence has been uncovered. More importantly, transgender advocates themselves argue the opposite: They deny that gender identity is rooted in biology. Their argument is that gender is completely independent of the body.

For example, Jessica Savano is a male-to-female transsexual, a 6-foot 4-inch model and actor who created a Kickstarter page for a documentary titled, “I Am Not My Body.” That title says it all. Savano posted a promotional video arguing that our core identity is completely disassociated from our bodies: “I know I’m not my body. I’m a spiritual being.”21

In other words, the authentic self has no connection to the body. The real person resides in the spirit, mind, will, and feelings.

In one segment of the video, Savano is filmed doing an audition for a transsexual movie role, reading from a script that says, “Why are you even looking at my penis anyway? I am a woman!” The viewer is viscerally struck by the contradiction as Savano claims an identity as a woman even while talking about having a male body.

The implication is that the body does not matter. It is not the site of the authentic self. Matter does not matter. All that matters is a person’s inner feelings or sense of self.

This radical dualism accepts a modernist, materialist view of the body in the lower story, and a postmodern view of the self in the upper story. The body is not seen as having any purpose or telos. It is merely a collection of physical systems—muscles, bones, organs, and cells—providing no clue to who we are or how we should live. Our physical traits give no signposts for the right way to deploy our sexuality.

And if the meaning of our sexuality is not something we derive from the body, then it becomes something we impose on the body. It is a social construction. Sexual identity is reduced to a postmodern concept completely disconnected from the body.

There are many misconceptions surrounding transgenderism, which I will address in chapter 6. People often confuse gender dysphoria with intersex. Or they conflate gender identity with social roles. Do girls wear pink while boys wear blue? Do men go to work while women raise children? Practices like these are dependent on historical circumstances, and the church should be the first place where people are encouraged to think critically and creatively about stereotypes.

The question raised by the transgender movement is much more fundamental: Do we accept or reject our basic biological identity as male or female? In the two-story worldview, the body is seen as irrelevant—or even as a constraint to be overcome, a limitation to be liberated from.

By contrast, a biblical worldview leads to a positive view of the body. It says that the biological correspondence between male and female is part of the original creation. Sexual differentiation is part of what God pronounced “very good”—morally good—which means it provides a reference point for morality. There is a purpose in the physical structures of our bodies that we are called to respect. A teleological morality creates harmony between biological identity and gender identity. The body/person is an integrated psychosexual unity. Matter does matter.

Body Obsession, the Body Rejection

Is it true that Western culture devalues the body? Don’t many people place a ridiculously high value on physical appearance and fitness? Consider the widespread obsession with diets, exercise, bodybuilding, cosmetics, plastic surgery, botox, anti-aging treatments, and so on. We are surrounded by Photoshopped images presenting unrealistic ideals of physical beauty. A Christian college professor once told me, “It seems to me that people tend to go in the opposite direction—they make an idol of the body.”

But to be obsessed by the body does not mean we accept it. “The cult of the young body, the veneration of the air-brushed, media produced body, conceals a hatred of real bodies,” writes theologian Beth Felker Jones of Wheaton College. “Cultural practice expresses aversion to the body.”22

Even the cult of the body can be an expression of the two-story dualism. An obsession with exercising, bodybuilding, and dieting can reveal a mindset akin to that of a luxury car owner polishing and tuning up an expensive automobile. Philosophers call that “instrumentalizing” the body, which means treating it as a tool to be used and controlled instead of valuing it for its own sake.

When we do that, we objectify the body as part of nature to be conquered. Feminist philosopher Susan Bordo writes, “The training, toning, slimming, and sculpting of the body . . . encourage an adversarial relationship to the body.”23 These practices express the will to conquer and subdue the body—and ultimately to be liberated from its constraints.

The radical ethicist Joseph Fletcher declared, “To be a person . . . means to be free of physiology!”24 Nature is treated as a negative constraint to be overcome.

So we end where we began: Our view of the body depends on our view of nature. Do we see nature as essentially good, a gift from the Creator to be accepted with gratitude? Or do we see nature as a set of negative limitations to be controlled and conquered? Of course, Christians engage in diet and exercise as well, but their actions should be motivated by a conviction that the body is a gift. We have a stewardship responsibility before God to treat it with care and respect.

To make the Bible’s positive message credible, it must be communicated not only in words but also in behavior by treating everyone with dignity simply because they are made in God’s image. Churches have at times used harsh and demeaning rhetoric to describe positions they disagree with, creating a negative stereotype that the media is happy to broadcast to the world. For several centuries Christianity was the dominant worldview in Western culture, and sadly Christians acquired some of the negative traits typical of dominant groups—for example, not really listening to minority groups or answering their objections but shutting them down with moral condemnation.

Today that response is no longer possible. But it was never right or necessary. Scripture gives the intellectual resources to answer any question with confidence. And those who are the most confident are also free to be the most loving and respectful toward others.

Healing Alienation

What is the biblical response to the secular moral revolution? Let’s start by addressing the two-level body/person dualism itself head-on. In later chapters, we will delve into individual issues.

We must start by expressing compassion for people trapped in a dehumanizing and destructive view of the body. The two-story worldview is “above all an attack on the body,” writes a Catholic theologian.25 We must therefore respond with a biblical defense of the body. We must find ways to heal the alienation between body and person.

The starting point is a biblical philosophy of nature. The Bible proclaims the profound value and dignity of the material realm—including the human body—as the handiwork of a loving God. That’s why biblical morality places great emphasis on the fact of human embodiment. Respect for the person is inseparable from respect for the body.

After all, God could have chosen to make us like the angels—spirits without bodies. He could have created a spiritual realm for us to float around in. Instead he created us with material bodies and a material universe to live in. Why? Clearly God values the material dimension and he wants us to value it as well.

Scripture treats body and soul as two sides of the same coin. The inner life of the soul is expressed through the outer life of the body. This is highlighted through the parallelism characteristic of Hebrew poetry (NASB, italics added):

“My soul thirsts for You, my flesh yearns for You.” (Ps. 63:1)

“Our soul has sunk down into the dust; our body cleaves to the earth.” (Ps. 44:25)

“Keep [my words] in the midst of your heart. For they are life to those who find them and health to all their body.” (Prov. 4:21–22)

“When I kept silent about [refused to repent of] my sin, my body wasted away through my groaning all day long.” (Ps. 32:3)

In one sense, our bodies even have primacy over our spirits. After all, the body is the only avenue we have for expressing our inner life or for knowing another person’s inner life. The body is the means by which the invisible is made visible. “We have no access to the free spirit apart from its incarnation in the body,” writes Lutheran theologian Gilbert Meilander. “The living body is therefore the locus of personal presence.”26

This wholistic biblical view is confirmed by everyday human experience. When you eat food, you do not say, “My mouth is eating.” You say, “I am eating.” When your hand is injured, you say, “I am hurt.” The two-level division of the human being is not true to our inescapable daily experience.

Philosopher Donn Welton sums up by saying that, in the Bible, the body “is not reducible to a material object or bio-physical entity, for it belongs to the moral and spiritual universe as much as it belongs to the physical world.” That is, the Bible does not separate the body off into a lower story, where it is reduced to a biochemical machine. Instead the body is intrinsic to the person. And therefore it will ultimately be redeemed along with the person—a process that begins even in this life. Welton writes, “In the final analysis, the New Testament does not argue for a rejection of the body but for its redemption and its transformation into a site of moral and spiritual disclosure.”27

A biblical ethic is incarnational. We are made in God’s image to reflect God’s character, both in our minds and in our bodily actions. There is no division, no alienation. We are embodied beings.

Walking Clay

At the time of the early church, this biblical view was radically counter-cultural. Ancient pagan culture was permeated by world-denying philosophies such as Manichaeism, Platonism, and Gnosticism, all of which disparaged the material world as the realm of death, decay, and destruction—the source of evil. Gnosticism essentially conflated the two doctrines of creation and fall: It treated creation as a kind of fall of the soul from the higher spiritual realm into the corrupt material realm.

Gnosticism thus trained people to think of the body “as a total other to the self,” writes Princeton historian Peter Brown. It was an unruly “piece of matter” that the soul had to struggle to control and manage.28 The goal of salvation was to escape from the material world—to leave it behind and ascend back to the spiritual realm. A popular pun at the time was that the body (Greek: soma) is a tomb (Greek: sema).

Gnosticism taught that the world was so evil, it must be the creation of an evil god. In Gnostic cosmology, there exist multiple levels of spiritual beings from the highest deity to the lowest, who was actually an evil sub-deity. It was this lowest-level deity who created the material world. After all, no self-respecting god would demean himself by mucking about with matter.

In this cultural context, the claims of Christianity were nothing short of revolutionary. For it teaches that matter was not created by an evil sub-deity but by the ultimate deity, the Most High God—and that the material world is therefore intrinsically good. In Genesis, there is no denigration of the material world. Instead it is repeatedly affirmed to be good: “And God saw that it was good” (Gen. 1:10, 12, 18, 21, 25).

Humans are presented as beings whose personhood includes being part of the earth from which they were created. The second chapter of Genesis says God formed Adam “from the dust of the ground” (2:7). The name for humanity, Adam, is even a pun in the original Hebrew, meaning “from the earth” (adamah = earth).

It was this walking, animated clay that God pronounced “very good” (1:31). It was this embodied, earthly, sexual creature that God described as reflecting his own divine image: “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness” (v. 26). Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, former chief rabbi of the United Kingdom, explains: “In the ancient world it was rulers, emperors, and pharaohs who were held to be in the image of God. So what Genesis was saying was that we are all royalty.”29 The early readers of Genesis knew the text was making the astonishing claim that all humans, not just rulers, are representatives of God on the earth.

Bethlehem Bombshell

What really set Christianity apart in the ancient world, however, was the incarnation—the claim that the Most High God had himself entered into the realm of matter, taking on a physical body. In Gnosticism, the highest deity would have nothing to do with the material world. By contrast, the Christian message is that the transcendent God has broken into history as a baby born in Bethlehem. The incarnation is genuinely physical, happening at a particular time and in a particular geographical location. “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14).

In the days of the early church, this was Christianity’s greatest scandal. That’s why the apostles repeatedly stressed Christ’s body: that in him “all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form” (Col. 2:9), that he “‘bore our sins’ in his body on the cross” (1 Pet. 2:24), that “we have been made holy through the sacrifice of the body of Jesus Christ” (Heb. 10:10). John even says the crucial test of orthodoxy is to affirm that Jesus has “come in the flesh” (1 John 4:2).

When Jesus was executed on a Roman cross, we might say he “escaped” from the material world, just as the Gnostics taught we should aspire to do. But what did he do next? He came back—in a bodily resurrection! To the ancient Greeks, that was not spiritual progress. It was regress. Who would want to come back to the body? The whole idea of a bodily resurrection was utter “foolishness to the Greeks” (see 1 Cor. 1:23).

Even Jesus’s disciples thought they were seeing a ghost. He had to assure them he was present bodily: “Look at my hands and my feet. It is I myself! Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones as you see I have.” He then asked for something to eat: “and he took it and ate it in their presence” to demonstrate that his resurrection body was genuinely physical (Luke 24:39, 43).

Not only did Jesus rise from the dead but he also ascended into heaven. We often think of the ascension as a kind of add-on, with no important theological meaning. What it means, however, is that Christ’s taking on of human nature was not a temporary expedient, to be left behind when he finished the work of salvation. Because he was taken bodily into heaven, his human nature is permanently connected to his divine nature.

Death, Be Not Proud

Finally, what will happen at the end of time? God is not going to scrap the idea of a material world in time and space as though he made a mistake the first time. The biblical teaching is that God is going to restore, renew, and re-create it, leading to “a new heaven and a new earth” (Isa. 65:17; 66:22; Rev. 21:1, italics added). And God’s people will live on that new earth in resurrected bodies. From the time of the early church, the Apostles’ Creed has boldly affirmed “the resurrection of the body.”

It is true that at death, humans undergo a temporary splitting of body and soul, but that was not God’s original intent. Death rips apart what God intended to be unified. A second-century theologian, Melito of Sardis, wrote that when “man was divided by death,” then “there was a separation of what once fitted beautifully, and the beautiful body was split apart.”30

Why did Jesus weep at the tomb of Lazarus even though he knew he was about to raise him from the dead? Because “the beautiful body was split apart.” The text says twice that Jesus was “deeply moved in spirit and troubled” (John 11:33, 38). In the original Greek, this phrase actually means furious indignation. It was used, for example, of war horses rearing up just before charging into battle. Os Guinness, formerly at L’Abri, explains: Standing before the tomb of Lazarus, Jesus “is outraged. Why? Evil is not normal.” The world was created good and beautiful. But now “he’d entered his Father’s world that had become ruined and broken. And his reaction? He was furious.”31 Jesus wept at the pain and sorrow caused by the enemy invasion that had devastated his beautiful creation.

Christians are never admonished to accept death as a natural part of creation. The Gnostics saw death as freedom from the encumbrance of the body. But for the early Christians, says Peter Brown, death “was a rending of the self that left the soul shocked and horrified, like a bereaved spouse or parent, at the prospect of parting from the beloved body.”32 Scripture portrays death as something alien—an enemy that entered creation with the fall.

And yet, it is a conquered enemy. “Death be not proud,” wrote the poet John Donne. For in the end, “Death shall be no more. Death, thou shalt die.”33 As Paul writes, death is “the last enemy to be destroyed” (1 Cor. 15:26). In the new creation, body and soul will be reunified, as God meant them to be. Eternally.

When the Bible speaks of redemption, it does not mean only going to heaven when we die. It means the redemption of all creation. Paul writes that the whole creation suffers pain and brokenness but that it will be liberated at the end of time: “The creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21). The gospel message is that the entire physical world will be transformed. Humans will not be saved out of the material creation but will be saved together with the material creation.

We cannot know exactly what life will be like in eternity, but the fact that Scripture calls it a new “earth” means it will not be a negation of the life we have known on this earth. Instead it will be an enhancement, an intensification, a glorification of this life. In The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis pictures the afterlife as recognizably similar to this world, yet a place where every blade of grass seems somehow more real, more solid, more substantial than anything we have experienced.34

Jesus’s resurrection is an eloquent affirmation of creation. It implies that this broken world will be fixed in the end. God’s creation will be restored. And you and I will live in that renewed creation in renewed bodies. At the end of the great drama, we will not be floating around in heaven as wispy, filmy, gossamer spirits. We will have physical feet firmly planted on a renewed physical earth. The Bible teaches an astonishingly high view of the physical world.

Revenge of the Body Haters

The New Testament concept of a bodily resurrection was completely novel in the ancient world.35 In fact, it was so astonishing that many simply denied it. In the second century, many Gnostics claimed to be Christians but they adjusted biblical doctrines to fit their philosophy. Denying the incarnation, they taught that Christ was an avatar from a higher spiritual plane who entered the physical world temporarily to bring enlightenment and then returned to a higher state of being. They insisted that he was not really incarnate in a human body nor did he really die on the cross. Spirituality had nothing to do with this world but only with escape to higher realms. As theologian N. T. Wright says, the Gnostics “translated the language of resurrection into a private spirituality and a dualistic cosmology.”36

Just as today, a privatized, escapist, otherworldly spirituality was far more socially acceptable. As a case in point, the Gnostics were not persecuted by the Roman Empire as the Christians were. Why not? Because a spirituality that applies strictly to the private realm poses no threat to power. As Wright explains, “Death is the last weapon of the tyrant, and the point of the resurrection . . . is that death has been defeated.” This explains why “it was those who believed in the bodily resurrection who were burned at the stake and thrown to the lions.”37 They understood that when Jesus was raised from the dead and given a new, resurrection body, God was inaugurating the promised new creation, in which all injustice and corruption would be wiped out—and as a result, they were empowered to take a stand against injustice here and now.

At his ascension, Jesus said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Matt. 28:18, italics added). With those words, he authorized his followers to establish his kingdom on earth by opposing evil and establishing justice. That’s what it means to live as a citizen of heaven. When Paul says in his letter to the Philippians that we are citizens of heaven, most Christians interpret that to mean we should look forward to leaving earth and going to heaven, which is our true home. But that is not what the passage meant to first-century readers. The city of Philippi in Greece was a Roman colony, where many had the privilege of Roman citizenship. The citizens of a colony were not supposed to aspire to go back to Rome. Their job was to secure a conquered country by permeating the local culture with Roman culture. By telling Christians they are citizens of heaven, then, Paul was telling them to permeate the world with a heavenly culture.38

That’s why C. S. Lewis calls Christianity “a fighting religion.”39 He means that disciples of Jesus are not meant to passively allow evil to flourish on earth, while looking forward to escaping someday to a higher realm. Instead they are called to actively fight evil here and now. The doctrine of the resurrection means that the physical world matters. It matters to God and it should matter to God’s people.

Today secular culture is falling back into a dualism that denigrates the material realm, just as ancient paganism did. As in the early church, it is orthodox Christians who have a basis for defending a high view of the human body.

Don’t Handle! Don’t Touch!

But doesn’t Christianity itself teach that the body is inferior to the spirit? That the body is a stumbling block and a cause of sin?

It’s true that at times negative attitudes toward the body have infiltrated the church. Many people have the idea that Christianity is against any form of pleasure or enjoyment. This is called asceticism, the idea that the path to holiness is severe self-denial. But the source of asceticism was not Scripture; it was Platonic and Gnostic philosophies. Because these philosophies regarded the physical world as inherently evil, they concluded that holiness could be attained by physical deprivation—fasting, poverty, solitude, silence, hard manual labor, drab clothing, the rejection of marriage and family, and other forms of austerity.

The ascetics of the ancient world were looked up to as the “spiritual athletes” of their day (the word asceticism is derived from a Greek term for athletic training). As a result, they influenced even Christians. This explains why even today there are strains of Christianity that teach a stern, tight-lipped asceticism—as though holiness consists simply in saying no to fun and pleasure. These versions of Christianity speak of the body as though it were shameful, worthless, or unimportant. They treat sexual sin as the most wicked on the scale of sins. They hold an escapist concept of salvation, as though Jesus died to whisk us away to heaven.

I once visited a Lutheran church where the pastor spoke repeatedly about asking for God’s forgiveness “so we can go to heaven,” about being confident that “we are going to heaven,” about thanking God that “we are going to heaven.” I began to wonder, Does this pastor think Christianity makes any difference in this life? Sermons like this one are more Gnostic than biblical.40 They give the impression the Bible is concerned only about what happens when we die.

Of course, spiritual disciplines such as fasting can be helpful, but they should not be motivated by the mistaken idea that the body is evil or worthless. The biblical text can be confusing because in some passages Paul uses the word flesh to mean the sinful nature (see Rom. 8; Gal. 5.) Just as in English, a word can have different meanings depending on the context.

Yet Paul soundly rejects the notion that holiness can be achieved through deprivation of the body. He describes ascetics as those who “forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods”—those who say, “Do not handle! Do not taste! Do not touch!” (1 Tim. 4:3; Col. 2:21). Rules like these do not work, he argues. “Such regulations indeed have an appearance of wisdom, with their . . . harsh treatment of the body. But they lack any value in restraining sensual indulgence”(Col. 2:23). Paul even warns that it’s a heresy to prohibit marriage: “For everything God created is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving” (1 Tim. 4:4).

Who Invented Matter Anyway?

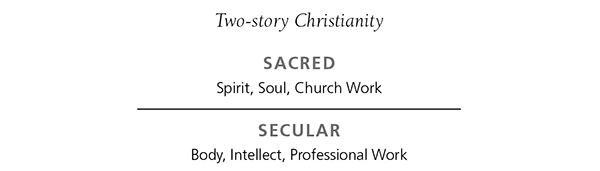

The influence of asceticism even created a Christian version of the two-story division—we call it the sacred/secular split. It’s a mentality that treats the spiritual realm as good and important while demoting the physical realm to a necessary evil.

The sacred/secular split is a major reason many Christians do not enjoy the power and joy that are promised in Scripture. They go to church on Sunday but do not think Christianity has any relevance to the rest of their lives. As C. S. Lewis writes, they regard the physical world as “crude and unspiritual.”

But Lewis offers a snappy rejoinder: “There is no good trying to be more spiritual than God. God never meant man to be a purely spiritual creature. . . . He likes matter. He invented it.”41

And in the end, he will redeem it. The theological image for the resurrection of the body is the seed: “The body that is sown is perishable, it is raised imperishable. . . . It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body” (1 Cor. 15:42, 44). The term spiritual body is often misunderstood to mean something ghostly and intangible. But the adjective does not tell us what the body is made of, rather what powers it. By analogy, a gasoline engine is not made of gasoline but powered by it. The great church father Augustine explains, “They will be spiritual not because they will cease to be bodies, but because they will be sustained by a quickening Spirit.”42 In the resurrection from the dead, our bodies will be fully powered and sustained by God’s Spirit.

At that time, what the ancient prophet Job said will come true: “In my flesh I will see God” (Job 19:26, italics added).

Contrary to asceticism, the Bible does not treat the body as the source of moral corruption. Instead it says sin originates in the “heart.” In Scripture, the word heart does not mean our emotions, as it does today. It means our inner self and deepest motivations, as we see in these passages: “Do not lust in your heart” (Prov. 6:25). “Their hearts are greedy for unjust gain” (Ezek. 33:31). God says, “I gave them over to their stubborn hearts to follow their own devices” (Ps. 81:12).

Jesus himself gave the definitive statement: “The things that come out of a person’s mouth come from the heart, and these defile them. For out of the heart come evil thoughts—murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, slander” (Matt. 15:18–19).

Ezekiel sums up the biblical teaching by saying humans harbor “idols in their hearts” (Ezek. 14:3–7). The mainspring of sin is not that we have bodies but that we put things besides God at the center of our lives and turn them into idols. Paul unpacks the idea by saying those who do not worship the transcendent Creator will worship something in the created world instead: In his words, they “exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator” (Rom. 1:25).

When we put anything in the place of God, that functions as our idol.

That’s why the Ten Commandments start with the command to love and worship God above all other things. When our hearts are centered on God, only then are we empowered to fulfill the rest of the commandments that deal with behavior—what we do with our bodies.

Body Positivity

But wait, doesn’t Paul also talk about the “body of sin” (Rom. 6:6 KJV)? And doesn’t that mean the body is the source of evil? No. The context makes it clear that Paul is saying the body can become an instrument of sin—but it can also become an instrument of righteousness: “Do you not know that when you offer yourselves to someone as obedient slaves, you are slaves of the one you obey—whether you are slaves to sin, which leads to death, or to obedience, which leads to righteousness?” (v. 16). The problem is not the body but sin. The body is merely the site where the battle between good and evil is incarnated.

This battle does explain why, at times, we do feel estranged from our bodies. Paul expresses that sense of self-alienation when he writes, “I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do” (7:15). Notice that he experiences sin as an unwanted, unwelcome, alien force within his body: “It is no longer I myself who do it, but it is sin living in me” (v. 17).

We have all had similar experiences of bondage and addiction—of compulsively doing things we do not want to do. In the same breath, however, Paul promises that we can be liberated: “But thanks be to God that, though you used to be slaves to sin, you have come to obey from your heart the pattern of teaching that has now claimed your allegiance” (6:17). It is possible to break the power of bondage to sin: “Therefore do not let sin reign in your mortal body so that you obey its evil desires” (v. 12).

The only appropriate response to such liberating grace is to “honor God with your bodies” (1 Cor. 6:20), or to put it more fully, “to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship” (Rom. 12:1). It is exciting to think God actually wants to relate to us in our bodies, loving our idiosyncratic shape and size, our bodily quirks, our physical appearance. God wants to love and interact with us not only spiritually but in our entire being.

Scripture even uses a striking bodily metaphor when speaking of the community of Christians: The church is the body of Christ. And it is sustained by physical eating and drinking, an act of bodily consumption: “Is not the cup of thanksgiving for which we give thanks a participation in the blood of Christ? And is not the bread that we break a participation in the body of Christ? Because there is one loaf, we, who are many, are one body, for we all share the one loaf. (1 Cor. 10:16–17). As Welton observes, “It, no doubt, came as a shock to those working within the framework of Greek thought that what Jesus offered was not his mind or soul but his ‘flesh’ or body, symbolized in the element of the bread.”43 In a biblical worldview, not only does the body have its own dignity but it also supplies images and analogies, metaphors and symbols for our participation in the spiritual world.

But isn’t this world fallen, and doesn’t that mean it is corrupt? Yes, but there is a danger of overemphasizing the doctrine of the fall, tipping it out of balance with the other doctrines of Scripture.

Biblical theology is woven from three themes: creation, fall, and redemption. All created reality comes from the hand of God and is therefore originally and intrinsically good. Humans are called to be stewards of the physical world—which includes our bodies—responsible to the One who made and owns it.

Yet all created reality is marred and corrupted by sin. Because humans were given responsibility for creation, its destiny is bound up with ours. We see this even in human experience—when a father is abusive, the whole family is likely to be dysfunctional; when a national leader is corrupt, the entire nation suffers. In the same way, when humans sinned, all of creation was put out of joint.

Finally, at the end of time, all creation will be restored and renewed by God’s grace. The Bible speaks of salvation using terms like restore, renew, redeem—all of which imply a recovery of something that was originally good. If humans were originally and inherently evil, there would be nothing to restore. God would have to destroy humanity and start over. It is only because sin is an alien force in God’s good creation that we can be rescued, delivered, freed, and restored. The body can once again become an instrument of godliness, as it was meant to be: “Offer every part of yourself to him as an instrument of righteousness” (Rom. 6:13).

Indeed, the reason the fall is such a tragedy is precisely because humans have such high value to begin with. When a cheap trinket is broken, we toss it aside without a second thought. But when a priceless work of art is destroyed, we are heartbroken. The reason sin is so tragic is that it destroys a human being—a priceless masterpiece that reflects the character of the Supreme Artist.

Of course, the Christian knows that the created world is not the ultimate reality. But that does not imply that it is worthless or contemptible. There are times, especially moments of crisis, pain, and suffering, when we are deeply grateful that the physical realm is not the sole reality—that there exists a transcendent, spiritual realm that is equally real. God is the sole self-existing, self-sufficient ultimate reality; the material world is dependent on him. That’s why we are called to “set your minds on things above, not on earthly things” (Col. 3:2). These verses are not meant to make us despise God’s creation but to intensify our reliance on God.

The church father Justin Martyr, writing in the second century, faced the same objections that we face today. In “The Dignity of the Body,” he writes this wonderful passage:

We must now speak with respect to those who think meanly of the flesh. . . . These persons seem to be ignorant of the whole work of God. . . . For does not the word say, “Let Us make man in our image, and after our likeness”? What kind of man? Manifestly He means fleshly man, for the word says, “And God took dust of the earth, and made man.” It is evident, therefore, that man made in the image of God was of flesh. Is it not, then, absurd to say, that the flesh made by God in His own image is contemptible, and worth nothing?44

The theological insights of Justin Martyr in the second century are still needed in the twenty-first century. As we face the social ills of our own day, we must move beyond denunciations that can sound harsh, angry, or judgmental and instead work to show that the biblical ethic is based on a positive view of the body as part of the image of God. The goal is not to win a culture war or to impose our views on others but to love our neighbor, which means working for our neighbor’s good.

How does this biblical and historical background give us better tools to understand secular morality? Now that we have surveyed the most controversial issues, let’s dive into each one in greater detail, answering the most common objections and identifying the dehumanizing worldview at its root, starting with abortion.