The Gathering

Constance was an excellent choice, in a peaceable area, a centre of communications westwards along the Rhine, north and east through Württemberg and Bavaria, with a choice of passable routes south through the Alps. The fertile lake shores provided abundant food and some very tolerable wine, while the lake was an inexhaustible source of fish. Admittedly the climate was damp, as Pope John was to complain, but generally mild and agreeable. For a brief moment the town was to become the centre of the Christian world – not only of the Latin, but also of the Eastern Church – the capital of Europe, and everyone concerned was conscious of being at the centre of grave events. Since so many participants, clerics, laymen and burghers alike, were literate, innumerable diaries, letters and accounts were written, many of which survive, and represent various diverse points of view.

Poggio Bracciolini, who took Bruni’s place as Pope John’s secretary, writing in Latin and Italian, a passionate collector of classic manuscripts, kept up a lively correspondence with his friend after Bruni returned to Florence in February 1415. Poggio seems to come from another world, that of Renaissance humanism, observing with detached interest the curious goings on of the churchmen, in intervals of liberating classical works from the neighbouring monasteries. Sir Thomas Forster, one of the English representatives, wrote confidential letters to King Henry V. Eberhard Windecke, Sigismund’s accountant, accompanied the King throughout the Council and later, and left a part-biography of his master in crabbed German. Equally lively, but in verse, was the work of Oswald von Wolkenstein, poet, soldier and diplomat, who had fought alongside Sigismund at Nicopolis, whose work would have to feature in any book of German comic verse that might ever be compiled.

As might be expected, the clergymen wrote the most voluminous accounts: speeches, sermons, memoranda and letters. The most useful and accessible of these is the diary of Cardinal Guillaume Fillastre. Sixty years old when the Council began, Fillastre was essentially a practical lawyer and an experienced administrator with an eye for detail. He had been a strong advocate of Benedict XIII at Avignon, but had moved over to Rome, and been given his red hat by John XXIII in 1411. Singlemindedly French, invariably critical of the English delegation – he found Robert Hallam, the generally popular Bishop of Salisbury, to be ‘malicious and arrogant’ – Fillastre was nevertheless a very accurate recorder. His diary is precise, accurate and rather dull, and gives full stress to the Cardinal’s own – certainly considerable – contributions. The Italian official, Jacopo Cerretano, gives a less opinionated version from the Italian point of view, wearily dismissing one attacker of the Curia: ‘However, he always talked in this vein.’

Another diary is anything but dull: that of Ulrich von Richental, ‘burgher and householder’, a resident of Constance, at the sign of the ‘Golden Hound’, who spoke personally with many dignitaries and conducted meticulous researches. With true Teutonic exactitude he enumerated all the visitors, who included thirty-eight cardinals and patriarchs, with 3,174 attendants; 285 bishops and archbishops with no fewer than 11,600 supporters; among the lay folk were ‘Our Lord the King,’ two queens, five princesses, thirty-nine dukes, thirty-two princes and royal counts: academics, doctors of theology and law, numbered 1,978 with 6,860 in their train, plus 530 ‘simple priests and scholars’. They were cared for by 171 physicians and 300 apothecaries, and entertained by 1,700 trumpeters, fiddlers, pipers and other musicians. While the royal court was in residence there were numerous balls and tournaments, and at least one play was performed. A good estimate for all those coming to Constance, over three years, Richental calculated as being 72,460.

With the help of Gephardt Dacher, commissioned by the Elector of Saxony to list all prominent visitors, the addresses of more than seven hundred common prostitutes were recorded; there were many more, mostly operating from stables and empty wine barrels, and an unknown number of more select and expensive ladies, one of whom earned 800 florins, although the time involved was not recorded. Oswald von Wolkenstein recorded his troubles with the Constance girls.

The mere thought of Lake Constance makes my purse hurt

It was there that I paid in ‘Haus zur Wilde’

Many schillings for amorous services.

‘Go on and pay!’ was their refrain

And angry was the roaring of the

Pimp Nesselwang:

Why did I not stay at home? – (the pimp demanded)

He took me for an idiot

Took my money and left only my purse

No more love for me in his house.

At the beginning of June, Richental was among the first to hear that Constance had been chosen, when the Town Council sent him to escort two papal emissaries in exploring the district. As soon as the decision was made, the prudent citizens began to buy up bedding and whatever else was thought might come in handy. There was very nearly a last-minute hitch when King Ladislas died on 6 August, probably of syphilis, to be commemorated with an enormous tomb in the church of St Giovanni Carbonara. If it had been possible to have scrambled back into Rome John would have been safe, able to proclaim a Council of his own. He was tempted; it would have meant risking Sigismund’s fury, but Sigismund was a long way off, and Bologna was still John’s city, and a strong base. His cardinals, less willing to take risks and for the most part committed to at least moderate reform, dissuaded him. It was not until 19 October that his legate, the Cardinal of Bologna, was able to restore papal rule in Rome, and by then John had started his journey to Constance.

Coping with so considerable an influx was a major task for the city fathers. Constance was not a particularly large town, with a population of between 6–8,000, including 1,500 burghers, but it was prosperous and experienced in dealing with foreigners; the principal bankers, Liutfried Muntprat & Company, had branches in Avignon, Bruges and Venice. Bürgermeister Hans Schwartzach and his council proved equal to the task. Every citizen had to provide accommodation at fixed prices, with the bed sheets changed every fortnight, and disputes settled by a board of arbitrators. Maximum prices for food were also laid down. Richental’s illustrations show, in addition to the usual meat, bear and heron were being offered for sale. Order was strictly kept, but serious offenders were quite often merely expelled: only fifteen death sentences were passed over the four years, and many commuted. With some surprise, Richental could list only twenty-six violent deaths, but some 500 corpses were also fished out of the lake.

The first of the magnates to arrive was Pope John himself on 28 October, after a difficult journey over the Alps, at one point being tipped out of his carriage into the snow, cursing jokingly and profanely. Very conscious of the advisability of projecting papal authority by a dramatic entrance, the Pope spent the previous night at Kreuzlingen Abbey, outside the walls, preparing his retinue and enlisting the Abbot’s support by conferring the coveted distinction of a mitre on him. In the morning of 28 October a magnificent procession entered the city, led by clerics and prelates, followed by white horses bearing the rood and a monstrance, followed by the Pope himself, under a golden baldachino, dressed entirely in white, mounted on a white horse with scarlet trappings, the bridle held by Count Rudolf of Montford and Berthold des Ursins, surrounded by pages holding candles and throwing money to the crowd, with nine cardinals in attendance.

Taking up his residence in the town’s finest house, the bishop’s palace, John had made a very satisfactory demonstration. The fact that he had actually arrived three days in advance of the due date was something unprecedented in the previous history of delayed and adjourned meetings. He had formally summoned the Council, was to preside over the inauguration as the accepted Pope and was reinforced by hundreds of Italian placemen; neither of the other claimants appeared; with Sigismund’s delayed arrival he had the field to himself: his was the ‘only show in town’. But Pope John was a realist, and well understood that he could not depend on all his cardinals, some of whom were inconveniently honest and eminent men, quite likely to prefer a root-and-branch solution in which all three claimants were eliminated. More comforting was the presence of his own banker, young Cosimo di Medici, with enough bullion and credit to encourage many potential allies.

The Council should have been opened on 3 November, but the Pope was taken ill, and it was postponed for two days. On 5 November the Council of Constance was inaugurated by the Holy Father, Pope John XXIII, now attended by fifteen cardinals, two patriarchs, and twenty-five bishops. A few days later five more cardinals arrived, bringing the news that the City of Rome had now accepted papal rule, and the Neapolitan danger was over. ‘Our Most Holy Lord the Pope’ – Zabarella’s honorific – could well believe that he was secure. The first formal session on 16 November was opened with a sermon from the Pope on the text ‘Speak ye every man the truth’, the irony of which was probably appreciated by those acquainted with John’s real character.

True to the Avignon standards of efficiency, the session went on to establish a secretariat: notaries and scribes to record, file and distribute the minutes and decrees, lawyers to help with contentious points, inspectors to supervise the voting, ushers to keep order – there must be no ‘loud noise, vituperation or laughter’ – all reporting to a Guardian of the Council, the soldier Berthold des Ursins. The cathedral was prepared for use as a conference hall, with the nave walled off and provided with three lateral rows of seating to accommodate various grades of dignitaries, with the humbler folk given folding stools on the floor. The Pope had two thrones to himself, one of which commanded a view of the whole minster, while the King was allowed a seat large enough to provide for three attendants.

John’s early arrival gave him the opportunity to establish a coherent party of his supporters, with the College of Cardinals as a nucleus, before any potential opposition appeared on the scene. Pope John therefore produced a draft Bull which described Constance as a continuation of Pisa, a contention which was to be the Pope’s first line of defence, stressing his legitimacy and suggesting that Sigismund’s participation, although welcome, was irrelevant.

There was no doubt in anyone else’s mind, however, that Sigismund would be firmly in charge and that his assertion of personal power had been welcomed with general relief as providing the only way out of the now intolerable dilemma. Although strictly speaking not yet Emperor, but only King of the Romans, Emperor-in-waiting, Sigismund did not need the formal dignity. By sheer force of personality, expressed sometimes by vigorous invective, and at least two threats of force, but more often by charm, and the capacity to outlast his opponents in argument, Sigismund controlled the Council. He was also much helped by Pipo Span’s excellent intelligence service. Until the King came in person no important official business could therefore be done, and other important participants were still missing. Fillastre considered the French and English to be essential and great weight was given to the opinion of the University of Paris’s delegations, quite distinct from those of the French King, but as more emissaries arrived some preliminary discussions began.

On 7 December the Italian cardinals presented their suggested programme, a highly political agenda, identical to that of the Pope; the decisions taken at Pisa were to be confirmed and John authorized to deal with his competitors by force if necessary. In future a General Council should be held every ten years (by which time John could expect to be firmly entrenched) and financial wickedness should be deplored – although without specific suggestions. The first crack in the college’s solidity appeared when the French Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly rejected his Italian colleagues’ proposal, insisting that Constance was by no means merely a continuation of Pisa, but independent and separate; the corollary of this being that Pope John’s position was not safeguarded.

A third memorandum from four cardinals seems to have been something of a joke, and largely consisted of complaints about the Pope’s frivolity and his habit of appearing improperly dressed, sleeping too late and his sluttish housekeeping but ended up with a warning that even popes must consent to have their authority challenged. A week later the Italians tried again, urging that a stern line be taken with the two popes already deposed in Pisa. Once more d’Ailly insisted that the matter should be left open.

The real challenge to both Curial solidarity and Pope John’s position was appearing as a mundane administrative decision. As a matter of convenience, the national delegations were meeting separately; the English and German respectively took to the refectory and the chapter house of the Franciscan monastery, while the Italians and French shared the Dominican convent. The cardinals kept themselves to themselves, never eating with laymen and meeting separately in the bishop’s palace or the dean’s house, although appearing as well at their own nation’s meetings.

Latin had always been a spoken language, distinct from the precise and conventional written forms. By the late Middle Ages the written and spoken forms had grown much closer – rhyme and stress had displaced quantity in verse, inspiring hearty drinking songs and romantic rondeaus; frequent abbreviations made writing speedier – surviving letters and notes written on any available scraps of paper or wafer-thin parchment are not beautiful objects. University examinations were still based on oral disputations, and any university student would have been a fluent, if not an accurate, Latinist. Although Latin was the official language of the Council fluency could not be expected from the lay delegates, who carried significant weight. The English nation’s sessions would probably have used English, borrowing technical terms and phrases from the Latin, but the fact that one single language was used in all the international meetings made debate easier and much more direct. The division by nations, adapted from the universities’ practice, was now transferred to the sphere of international diplomacy. When formally adopted, and incorporated into the Council’s voting protocol, the innovation was to prove decisively important.

Jan Hus also made an early arrival, on 3 November. Not untypical of other academically brilliant people, Hus was a simple soul, incapable of chicanery, confident that he was right and that others, once they had been clearly instructed, would agree with him; compromise did not come easily to Master Jan. A political innocent, he had never been outside his own country, where however aggressive was the opposition he had always enjoyed massive popular support and powerful protection. It was typical that before Hus left Prague both the papal inquisitor, Bishop Nicolas of Nazareth, and the Archbishop had given assurances that he was no heretic, but a true and faithful Catholic. Another guarantee of Hus’s standing was King Sigismund’s arrangement to meet Hus en route, so that he could enter Constance as a member of the royal party, and his provision that three Bohemian nobles, Jan and Jindrich of Chlum and Václav of Duba, should act as his escort. Hus’s first major error was to miss the rendezvous with Sigismund, who had been detained at Aachen, and press on to Constance instead of waiting for the King.

Jan of Chlum reported their arrival in the town to Pope John, and their residence at Widow Fida (Pfister)’s house, still there in what is now Hussenstrasse, informing him of the personal safe-conduct that Sigismund was sending, and the clearances received from Prague. He was reassured by the Pope that ‘if Hus had killed my own brother, nobody would be allowed to trouble him, while at Constance’. This was, however, one of those diplomatic undertakings that Pope John handed out very freely. Hus, at that stage, presented a minor problem: the Pope’s immediate concern was the conundrum posed by the expected arrival of Pope Gregory’s envoy, Cardinal Dominici of Ragusa, ‘Friar John Dominici, the so-called Cardinal’ as Cerretano dismissively termed him. Was it proper that Pope Gregory’s coat of arms be fixed to Dominici’s designated lodging and would he be permitted to enter the town wearing his cardinal’s red hat? Discussions on the subject occupied the Council for some time; the fact that he was suffering both from gout and a skin infection also occupied the Holy Father’s mind.

Only Hus’s particular enemies, now led by his former friend Stephen Páleč and the sinister Michael de Causis, noted his arrival. On the strength of a rumour that Hus might be planning an escape they persuaded the Curia to order his arrest on 28 November, which was effected by the Bürgermeister, supported by two German bishops. Jan of Chlum would have resisted, but Hus insisted on going with them, and was detained. Taxed by Chlum with reneging on his undertakings the Pope replied that it was not at his orders, but at the insistence of the Curia – ‘and you know how things are between us’ he added, expressing his apprehensions as to the Curia’s attitude to his own claim.

Filling in time, the Council chose twelve members to start proceedings against Hus. There was to be no courteous academic debate, for which Hus had prepared, but a continuation of the trial first demanded by Rome four years previously. That it was to be nothing more than a show trial is evidenced by Cerretano’s reference to an examination of ‘John Hus, the Wycliffite, and his books and wicked doctrine’. Thomas Polton, an English lawyer, reinforced this attitude in a petition that, although important decisions had to wait for the full Council, surely ‘measures against the Wycliffites and other heretical supporters of the faith, in particular against the heresiarch Hus, who is now in your hands [should] be put into real execution without delay or procrastination’.

On Christmas Day, at two in the morning, King Sigismund himself arrived, at the head of a fleet sailing from the port of Überlingen, arriving at the bay today commanded by the colossal statue of Imperia. The royal retinue progressed to the cathedral on foot before dawn, with Hungarian nobles bearing the imperial regalia – his father-in-law, Count Hermann of Cilli, holding the mace – and the Elector of Saxony acting as sword bearer, with a naked blade held over the King’s head, followed by Queen Barbara, slim and elegant with her ladies in attendance. Mass was sung by the Pope, but the King read the Gospel; as the successor of Charlemagne, reigning unquestioned over what was to be the largest gathering of European magnates ever assembled, he must have enjoyed reading that day’s text: ‘There went forth a decree from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be taxed.’ The church service went on for nine hours, which must have tired Sigismund’s patience – if indeed he stayed, as Richental recorded.

The royal party settled into St Peter’s Abbey – Peterhausen – on the right bank of the Rhine. A good reason for living outside the walls was the ‘wild unruliness’ of the Hungarians, unaccustomed to the placid existence of a small German town. Following the royal party Pipo Span arrived with 150 horses, Count Frederick of Cilli, the king’s son-in-law, with 300 horses, two archbishops with 178 horses between them. So numerous a train of Hungarians, never the most sedate of men, was unlikely to suffer gladly the tedium of waiting for some action and trouble duly occurred. The men of Peterhausen solved that problem by ambushing and beating the Hungarians, and the royal family moved into the town, where they took separate lodgings. All the major participants in the Council lived cheek by jowl, in a very small area: it was no place for secret diplomacy and one of the reasons for the Council’s success would be the very public manner in which all the discussions took place. A good deal of everyone’s time was spent out of doors, where mobile bakeries produced fast food at all times.

Sigismund was immediately faced by Jan of Chlum’s protests at Hus’s arrest. It was an unwelcome diversion from the more important business and the King was initially furious, knowing well that this would cause trouble in Bohemia, although without imagining on what a scale this would be, and angry that his own Imperial safe-conduct had been ignored; but there were more vital matters to be dealt with and Sigismund allowed himself to be mollified and convinced by legal arguments. If Hus were judged heretical the safe-conduct was invalid; if not, it would not be needed. Hus therefore remained a prisoner, at first in reasonable comfort, but soon transferred to the Dominican monastery – now the Insel Hotel – where he was confined in a small damp cell: he was, as it were, placed as an item of further business and ignored, with his request for a lawyer refused.

King Sigismund lost no time in proving that the Council was to be run not by Pope, cardinals or prelates, but by him, personally. Christmas festivities were still in full swing when, observing the civilities, he asked Pope John to call a meeting for Saturday, 29 December at which the King declared that nothing of importance was to be attempted before the arrival of all the national delegations, expected now by 14 January. In the meantime Sigismund intended – again with proper politeness – to appoint committees, which would include men of all ranks and conditions, in order to propose Church reforms ‘in head and members’ – that is, beginning with the Pope. John’s early hopes of being able to push through his own simple agenda were frustrated, but the only response from the Curial party was to badger the King about the cost of living, the problems caused by all the horses being brought into the town and the difficulty of finding lodgings. Meeting again on New Year’s Day, the King assured the complainants there would soon be room found for the horses outside the city, but reminded them that their prime object was to end the schism, and that ‘the case of John Hus’ and other ‘minor problems’ ought not to interfere with this.

Delegations from all parts of Europe duly arrived in Constance in the New Year. The generals of the mendicant Orders, Franciscans and Dominicans, came – the latter were ‘received with less state’ than their rivals. Much greater retinues accompanied the military Orders: the Grand Master of the Hospitallers came with a hundred horses, the Commanders of the Teutonic Knights came with a hundred and fifty beasts, which fortunately they sent away. Constance witnessed the first appearance in the West of a powerful Polish representation, headed by the Archbishop Nicholas of Gnesen with six hundred horses. Among the accompanying bishops was Duke John of Leslaw, who brought with him a barrel of beer ‘of which I, Oldřich Richentzl, had a draught’. Lord Swartz Safftins (Sawiftz or Cencius) was the best swordsman at the Council, and a reliable guard to the eventual Conclave, but his fellow-Pole, Lord George of End, was soon in trouble. George’s men set up as brigands, and after they raided a boatful of grain Lord George was arrested, but his squire, attempting to escape in full armour, was drowned, and Lord George forced to promise future good behaviour.

The English delegation was considerably smaller, with only some two hundred horses, but with seven wagons and ‘twenty-two sumpter horses, that carried apparel and other things’. Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, with three trumpeters and four fifers, led the group, but its most influential member was Robert Hallam of Salisbury, accompanied by Bishop Ketterick of St David’s, Sir Walter Hungerford, later distinguished at Agincourt and Bishop Fox of Cork. The young King James of Scotland being a part-guest part-prisoner in London between 1406 and 1424, there was no Scottish embassy. Scandinavia was patchily represented, their main interest being to ensure the canonization of their own St Brigitta.

Byzantine nobles and Minoel Chrysolaras represented Emperor Manoel, hopefully seeking support against the Turks and offering to mediate between Hungary and Venice. Richental reported that ambassadors came from ‘the two kings of the Turks’ (there were indeed then two Turkish claimants) and from Russia. Certainly the Voivode, Mircea the Old of Wallachia, was represented, and Duke Vitold of Lithuania came, with the prestige of his victory with the Poles over the Teutonic Knights at Tannenberg five years previously. ‘Most of them were utter heathen,’ Richental sniffed, ‘some schismatics, some worshipped Mohammed’: it was indeed a truly international gathering. The orthodoxy of John of Wallenrode, Archbishop of Riga, who became one of the most prominent leaders of the Council, would, however, hardly be questioned.

National embassies aside, the most important delegations were naturally those sent by the other two rival claimants. Benedict’s embassy was the first to make a formal appearance, on 8 January, jointly with that of King Ferdinand of Aragon, the only one of Benedict’s Spanish supporters to send a delegation at that time. Four days later, after due apologies for their delay – bad roads and the plague – they presented their case: their Pope would be at Nice during April next; if the King and his rivals would come, then Benedict ‘would act so as to please God and content the world’. Ferdinand’s ambassadors assured everyone on his behalf that their King ‘would offer weighty support’ to any effort to end the schism. Vague enough proposals, they were dustily received by Sigismund, who quoted the parable of the wise and foolish virgins and congratulated Pope John on having got to the Council on time. For the moment nothing more was done.

The Gregorians had a more affable reception, when they made their official entry on 22 January. This was an impressive delegation, headed by the Elector Duke Ludwig of Bavaria-Heidelberg, son of the former Emperor Rupert, Count Palatine and a faithful supporter of Sigismund, at whose side he had fought at Nicopolis. He was accompanied by Cardinal Domicini – in his red hat – together with a patriarch and three German bishops. Ludwig was able to give his personal undertaking to the Council that Gregory would indeed abdicate, but insisted that this was contingent on his being first recognized as the rightful Pope. This was something that the Council could not yet countenance, and again the case was placed on hold, but with the unstated assumption that eventually that condition would be accepted: anything Sigismund and Ludwig agreed between them was as good as settled. It was the first indication that Pope John’s fate was sealed.

For the time being John continued to act as the acknowledged Pope, and officiated on 1 February at a splendid festival in which St Birgitta of Sweden was canonized (this was the second of three such ceremonies: the first was by Boniface in 1391 and the third, to make sure, by Martin V in 1419). Birgitta’s sanctification provoked some grumblings, particularly from Jean Gerson: her claimed miracles were suspect, her visions dubious, and there were far too many modern saints, which devalued the currency; but international concord was the imperative, and the Scandinavians were allowed their saint, and celebrated with a banquet. Another impressive ceremony, that of Candlemas, was enacted the next day, with the Pope in full pontifical dress and in the presence of King Sigismund, blessing the candles to be used in the following year, after which candles were thrown down to the crowds and distributed to the prominent guests.

Clear party lines were now forming. Among the cardinals, d’Ailly and Fillastre were in their different ways both reformers, eager to push things on without damaging the institutional prestige of the papacy or cardinalate. Francisco Zabarella, the Cardinal of Florence, renowned as a canon lawyer and at the age of eighty greatly respected, ensured that all procedures were strictly legal; between them these cardinals were able to push the reluctant Italian conservatives into agreement. Among the nations the Germans consistently argued for quick action on reform, although it was Robert Hallam for the English who suggested the boldest strokes. While he was alive the Anglo-German alliance was solid, and at one with King Sigismund. The French, by contrast, were divided between the King’s party, that of the Duke of Burgundy, and the University of Paris. The first two voted politically, generally at odds with each other while the University delegation, with Gerson the outstanding member, were consistent reformers, usually co-operating with the two French cardinals.

It was Cardinal Fillastre, towards the end of January who, very respectfully, took the first initiative to push Pope John into abdication. He had been appointed by John, and was conscious of the Pope’s real merits, often obscured as they were by blatant bad behaviour. After sniffily noting that ‘the English and the Poles had now arrived, and were talking a great deal of plans for the peace of the Church, and proposing nothing definite…’ the Cardinal circulated his own ideas. Admitting John to be the lawful Pope, was it not his duty to abdicate, if this was the only way to restore unity, as a good shepherd lays down his life for his sheep? And if he does not volunteer, it would be legal and indeed necessary to compel him. But he ended with an appeal – ‘let us humbly and devoutedly entreat our most holy Lord John, and the Supreme Pontiff’ – to do the decent thing. Knowing his master well, Fillastre added this would not be to his financial disadvantage: ‘He must be assured that the Church will provide more richly for his future position than he would ask. No fear of poverty should deter him a moment from so great a benefaction, so bright a glory, and so splendid a reward.’

John’s Italian supporters, reinforced by his recent appointment of no fewer than fifty Italian bishops and papal officials, all of whom qualified for the vote, angrily objected. Fillastre and d’Ailly scotched this in their very different ways: the scholarly d’Ailly quoted scripture and the Fathers; Fillastre, blunt and direct, dismissing the Italians as ‘sycophants’, but both contending that all clerics, of whatever rank, should be allowed to attend and vote, as well as any qualified academics and representatives of kings and princes. Fillastre savaged the Italian pretensions based on the number of bishops with often very small sees: ‘Whoever you are … I venture to tell you that in the Gauls, the Germanies, England, and Spain there are a thousand priests of parish churches, each one of whom has a larger district to administer than many prelates, and the care of more souls. Justice would admit these men.’ Even extending the franchise might not be enough to outweigh ‘the Italian influence’. Fillastre again:

Now the law was clear, that votes should be counted by heads, but there were more poverty-stricken prelates from Italy than from well-nigh all the other nations put together. Besides, our Lord Pope had created an excessive number of prelates in camera, over fifty. There was also a rumour that he had tried to attach many more to himself by means of promises, bribes, and threats. So if votes were counted by heads, nothing would be done except what our lord wanted.

That problem was solved by the English delegation, who suggested to the Germans the formalization of the existing national divisions – France, Italy, England and Germany, each with equal voting power. Within nations all doctors of law or theology, and all representatives of the lay rulers would be allowed to vote; in practice many others joined in. One record of the French nation listed priors, university professors, archdeacons and miscellaneous clergy and monks, including two only described as sine titulo. The English team was equally diverse, ten bishops, seven abbots, twenty-seven doctors of theology and law, twenty-five Masters of Arts, more than sixty representatives of corporate bodies and over one hundred literati, attending the Council at various times. National assemblies, it was agreed, were to be organized by a president, elected every month. Once a nation had decided on a proposal, it was to be put to a general meeting of the nations before being formally submitted to the Council. All effected rapidly and without fuss, it was an astonishing achievement, and one that ensured the Italians, and with them Pope John, would be relegated to a minority, since the three other nations were determined on a rootand-branch solution.

The Council had begun following the traditional pattern of a general council of the Western Church, presided over by a Pope, but when John XXIII was deposed, as was becoming more inevitable, there would be no Pope. It was Sigismund, as ‘Protector of the Council’, who took charge, but as a layman, and a very busy one at that, he could not be expected to oversee the detailed work. This was done, very democratically, by the deputies of the nations, elected or confirmed every month, at the same time as the nations elected their own president. At frequent intervals the deputies met in a committee chaired by a ‘President of Presidents’, who also acted, sometimes jointly with Sigismund, in issuing official conciliar letters. In 1415 this post was usually filled by Jean Mauroux, Patriarch of Antioch, and Robert Hallam of Salisbury; the following year, when the influence of those two supporters of King Sigismund was being questioned, the office was subject to an election every week.

Much of the preparation of business, of research and investigation was carried out by commissions – ad hoc sub-committees, charged with a specific task. This could be collecting evidence against popes or heretics, or proposing detailed reforms, in which deputies worked together with cardinals. These commonplace administrative arrangements were in fact revolutionary. The authority of pope and cardinals was simply excised. The Pope had no role other than that of a master of ceremonies, and the College of Cardinals had lost its corporate power. They might meet together as often as they wished, but their only part in Council affairs was as individual members of their own national delegation. Admittedly the nations at Constance were not synonymous even with the emergent nationalities of the time. The Spanish nation, for example, included three Spanish realms, and Portugal, at war with each other for a large part of the fourteenth century, as well as Sardinia and Sicily. The English delegation was the most homogeneous, but its claims to represent Scotland and Gaelic Ireland were at least questionable. Both national meetings, and those of the deputies were held in private, although guests might be invited, and were frequently lively, while the General Sessions were more dignified. One of the two ‘Promoters’, an office akin to that of Company Secretary, presented the items previously agreed by the nations which were read out and formally passed.

Events began to move with extraordinary rapidity, not only day by day, but even hour by hour. Formal meetings were replaced by debates within the nations, by secret conversations, often faithfully reported by spies, and by hastily convened committees. Important reinforcements for Pope John arrived. Duke Frederick of Austria, already secured for the Pope at Merano, rode in on 18 February, with three hundred horsemen, joined a few days later by Archbishop John of Mainz, the senior imperial Elector, Arch-Chancellor and Count of Nassau, wearing armour under his scarlet robes, at the head of six hundred horsemen, including eight counts and many knights. No bribes from Pope John were necessary to secure the Archbishop’s support, since he had been a long-established enemy of Sigismund, but sixteen thousand florins were needed to buy the allegiance of Count Berhardt of Baden, who controlled the country on the far bank of the lake. With such weighty allies the Pope could depend on help if the worst came to the worst.

The first intimation that this might be inevitable had come on 15 February when the Bishop of Toulon was sent to persuade the Italians to join in pressing for John’s abdication, which he did with ‘such refinement, persuasiveness and elegance of diction that he charmed the ears of everyone … moving many to tears of pleasure’ that they agreed, but doubtless with the Pope’s previous consent. Next day, after informal approaches had been made suggesting that the most helpful course would be John’s graceful resignation, the Pope summoned an evening meeting of the Council. Like all his predecessors, John agreed in principle but subject to conditions: his competitors were to be stigmatized as heretics and schismatics while he, the true Pope, was laying down his office for the good of Christendom; there would also need to be some financial compensation. More negotiations, deputations and redrafts followed. The cardinals in particular were divided, nervous that John, who had been and was currently being accepted as the Vicar of Christ, and who had appointed many of them, should not be too harshly treated; he must appear, at any rate, to have abdicated voluntarily, rather than to have been deposed by a Council which included so many diverse members. If a Council were to be acknowledged as superior to a Pope, then at least it should be a Council in which the College of Cardinals played the leading part as they had done at Pisa; and this clearly was not happening at Constance.

It took another ten days of discussions before an acceptable formula could be presented. On 25 February the Pope was firmly told by the Germans that the Council had the right ‘in the name of the Universal Church’ to order his abdication, by threats if need be, and even to hand him over to the secular arm – the formula used to burn heretics.

John was not only a realist, but had a magnificent sense of theatre. If he was going to make the most solemn of promises (for which he never had too much reverence) it should be done splendidly. On 1 March, at a meeting held in his own quarters, in the presence of King Sigismund, he gave his formal promise to resign, not conditionally on the removal of the two claimants but ‘if my resignation may give peace to the Church and end the schism’. The Second General Session of the Council was immediately announced for the next day, in the cathedral. When John, in the full majesty of papal robes, read the prepared formula, at the words ‘I vow and swear’ he knelt before the altar, placed his hand on his heart and added: ‘I promise to fulfil this.’ Sigismund, not to be outdone, removed his crown and kissed the Pope’s feet; a Te Deum was sung, with a sobbing congregation, and it seemed that at last the schism was really going to end.

In the morning of Monday, 4 March Sigismund formally received the undertakings of Pope Benedict and King Ferdinand of Aragon confirming the proposed meeting at Nice and promised that armed with John’s resignation, he would himself attend, bringing with him a number of cardinals and prelates as advisers to negotiate Benedict’s abdication. Pope John attempted to insist that he too must go in person, and abdicate once Benedict had done so, but the Council, aided by Sigismund’s intelligence service, suspected that once out of Constance John would find a way either to return to Rome or, with Burgundian protection, set up in Avignon. Although the envoys said privately that Benedict ‘would conduct himself seriously as he was accustomed to’, it was still nothing more than an agreement to agree: the unspoken commitment was that if Benedict did not agree to abdicate, at least Aragon, and probably Castile and Navarre, would terminate their support. As a precautionary measure, Sigismund had the city gates manned to prevent attempts to escape.

On the next day, Tuesday, the ambassadors of the King of France arrived, led by the other Duke Louis of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, Upper Bavaria (also Ludwig but here given the French version of his name in order to avoid confusion), brother-in-law of King Charles, asking for a full session of the Council to be held in their honour: they were put in their place, and pointedly asked to wait.

The weekend of 9 and 10 March was busy. On the Saturday Sigismund received Pope Gregory’s envoys, who confirmed that they were mandated to offer his resignation. On the Sunday attention was diverted by a splendid ceremony in the cathedral at which Pope John presented Sigismund with a golden rose – the highest mark of papal favour – which the king ‘received very reverently … and held in his hand throughout the Mass’. After the presentation Sigismund rode through the city exhibiting the rose to the crowds, accompanied by twenty-three trumpeters and forty fifers. It was the last occasion that Pope John publicly performed his pontifical role.

Serious business recommenced on Monday the 11th with an informal General Assembly in the cathedral when the question of a new papal election was openly debated. A fine row began when Archbishop John of Mainz stood up and said that unless Pope John was re-elected, he would quit the Council. The Patriarch of Constantinople, a relatively minor figure in spite of his title, shouted out in Latin, ‘Who is that person? He should be burned!’ Upon which the Archbishop stalked out and went home. On Thursday the 14th the presidents of France, Germany and England told Pope John that he should immediately mandate representatives, chosen by the Council, to perform the act of abdication, and that he should undertake not to try to leave or dissolve the Council.

John agreed that he would not attempt to leave, and would excommunicate anyone who did, but modified this the next day by refusing to appoint delegates to act on his behalf. It was generally suspected that he intended to abscond, and this seemed confirmed when Cardinal Peter Hannibaldo, one of the Pope’s most reliable allies, was stopped while riding out of the city. When on the next day the English, German and French nations were called together by the King, it was agreed that the Pope must promise not to leave, nor permit anyone else to leave, before the abdication was finalized. On Saturday the 16th the Pope assembled his supporters – who included on this subject d’Ailly and Zabarella – and confirmed that he would prefer to resign in person, in the actual presence of Benedict. The French and Italians were weakening, and on the 17th asked for more time. By Tuesday the 19th the English had exhausted their patience, and early in the morning demanded the Pope’s arrest. With Sigismund at their head, the English and German deputations marched to the Dominican monastery where the French and Italians were meeting. When they were received with open hostility the King lost his temper and ordered those who were in fact subjects of the Empire, rather than of the French King, to leave immediately; ‘Now we shall find out who is for the Union of the Church and faithful to the Roman Empire.’ The royal anger (Sigismund could time his rages well) worked and the French backed down. In the afternoon Sigismund and Bishop Hallam visited the Pope, who complained that he had been grossly misjudged, that he was ill and suffering from the cold and damp of the lakeside town; no difficulty there, the King replied, there were many pleasant nearby spots where the Pope could be accommodated; that it should be under secure guard was not stated.

A Papal Fugitive

John believed, with fair reason at this stage, that if he left Constance, the Council would automatically be dissolved: it had been summoned by him, and acknowledged him as the rightful Pope; no resignation formula had yet been agreed. If there could be no Council without a Pope, John’s absence would render all further acts of the Council invalid. Losing no time, with Ulrich von Silverhorn, a Swabian knight, as the messenger, Pope John and Duke Frederick of Austria made arrangements for the following day, the 20th, when a tournament had been organized between the two groups of knights, one led by Fredrick of Cilli, the King’s son-in-law, the other by the Duke. With everyone’s attention focused on the tournament taking place in the open ground to the north of the town, the Pope, dressed as a groom, hobbling with the gout and carrying a cross-bow, attended only by a chaplain and a lad, stole out of the city southwards, along the Gottlieben road on the left bank of the Rhine. When the Duke was quietly told that the Pope had escaped, he conceded the last joust and made an unobtrusive exit with his steward and page. The fugitives met at the village of Ermatingen, then riding on to Schaffhausen, where they arrived close on midnight, thirty miles from Constance and safely within the Duke’s lands.

The crisis that now existed had been developing for some days and Sigismund was well prepared. The next morning (Thursday the 21st.), Sigismund and his supporters rode round the town, trumpets sounding, to reassure the frightened citizens, and summoned a meeting of the nations: the cardinals assembled separately. Immediately after the meeting of the nations the King called the Imperial princes together and charged Duke Frederick with treason. Four hundred German states, cities and individuals promptly confirmed their support in writing – Richental himself wrote more than fifty letters, which were immediately despatched to Duke Frederick. On the following Monday another formal meeting delivered the verdict: Frederick was outlawed, his authority dissolved, and his goods confiscated. Richental related that ‘all joined in the attack on Duke Frederick and everyone made ready to take the field with food, guns, powder and other implements of war, and went out to war with all their might’. Three days later the invasion of Frederick’s territory began. It was all accomplished with the energy of which Sigismund was often capable.

Speed was essential, for Pope John was managing to gather considerable support. The Duke of Burgundy, Jean Sans Peur, Sigismund’s former ally at Nicopolis, was pursuing his own agenda. If the Duke could gain control of Pope John, and remove him to Avignon, together with a respectable number of cardinals, and the support of Cardinal John of Nassau and the Duke of Austria, he could oust both Sigismund and King Charles of France from their European hegemony. The cardinals were not unsympathetic; they had been sidelined, and were resentful. On Friday the 22nd three senior cardinals, Orsini, the oldest member of the college, the Savoyard Amadeus Saluzzo and Fillastre himself, were sent to convince Pope John of the error of his ways. They were accompanied by Duke Louis of Bavaria and the Archbishop of Rheims to argue the same case on behalf of the French King, but before they reached Schaffhausen, John, following the military maxim that attack is the best form of defence, issued an open letter to the French court and the University of Paris which appeared in Constance on the Saturday. The English, it claimed, were at the bottom of the trouble, and responsible for setting the French and Italians at odds: with only three prelates and nine other churchmen at the Council they were ludicrously overplaying their hand. Robert Hallam, a mere bishop, had grossly insulted the Holy Father. Influenced by these troublemakers King Sigismund had taken upon himself to control the Council, which was the prerogative of the Vicar of Christ. All cardinals and Church officials, under pain of excommunication, were ordered to report to him at Schaffhausen within seven days.

When therefore on the Sunday morning nine obedient cardinals, all but one Italians, left to join Pope John it seemed as though the Council had disintegrated. Those who remained included d’Ailly and Zabarella, the most influential members of the college, but they had already evinced some support for the majority by refusing to attend a meeting called by Sigismund ‘fearing that the Council might be planning against our lord Pope’: which by then they most industriously were.

On the Monday morning (the 25th) the Archbishop of Rheims returned from Schaffhausen prepared to report to a General Assembly held the next day. It was a very different story from that given by the Pope to the French in his open letter of Saturday. Pope John had gone to Schaffhausen merely for a change of air; he was already feeling the benefit: he had every intention of resigning, but would do so only jointly with Benedict, at Nice or some other convenient place. Sigismund’s intelligence service had, however, doubtless relayed the true story, and the Council’s distrust of Pope John was increased. Those cardinals who had remained in Constance were in a quandary. They had already decided that John must go, but the manner of his resignation was vital, and must not be allowed to ruin the authority of the papacy for ever; or that of the cardinals, who, very pointedly, were not asked to the General Assembly called for the following day.

Tuesday 26 March began with a morning meeting of the nations in which draft proposals were prepared for an afternoon’s plenary session. A statement was prepared confirming that the Council continued in being, even in the Pope’s absence, and that no one was allowed to leave without due authority. It was followed in the afternoon by the Third General Session, presided over by d’Ailly, with Sigismund present in full imperial robes. Of the other cardinals only Zabarella was present, who read the morning’s resolution, which was unanimously agreed. That evening the deputation sent to Schaffhausen returned, bringing with them two of the now-repentant cardinals who had deserted on Sunday, one of whom was the only non-Italian to have joined Pope John. They were met without enthusiasm and even with a few jeers, and went immediately to a conference with Sigismund, the deputies of the nations and the other cardinals. After the formal meeting was closed, the King and the national representatives heard a deputation of cardinals, who insisted that a Pope must indeed remain the final authority, but promised that next day they would be able to give all the necessary assurances that John really would go. Since at the same time news came that the Pope had renewed his peremptory orders for all the cardinals to come to Schaffhausen the meeting broke up with some very angry scenes.

On Wednesday the 27th a public meeting heard the Pope’s case presented by the cardinals; of course John would keep his word, and would give an irrevocable undertaking to the College of Cardinals that if any three of them should so decide he must abdicate. They had full authority to effect this, even against John’s own will; but he intended to stay where he was, and needed at least some of the cardinals and officials with him. Meanwhile no action should be taken to discipline Frederick of Austria. By then, however, John’s credibility was exhausted; only the cardinals continued to support him, and even they were wavering. Their report from Schaffhausen was received only with contempt. King Sigismund and the national representatives impatiently pushed aside the cardinals’ efforts at reconciliation and drafted a radical solution, to be presented to the full Council on Saturday. Fillastre, who had been the leading spirit in the final endeavour to bring Pope John back to the fold, complained that ‘the nature of the action to be taken in the coming session had still not been fully explained to the cardinals or to the ambassadors of the King of France, who were indeed not respectfully treated or received even by the French nation’. Sulkily, they decided not to attend the Saturday session, but Sigismund bullied and cajoled them into coming, assisted by the news that on Friday night (the 29th) Pope John himself had in fact already thrown in the towel by riding off to find a refuge thirty miles away in Duke Frederick’s castle at Lauffenberg. He had gone with the Duke, some armed men and ‘a handful of prelates’. ‘Expecting to escape from one peril,’ Fillastre reflected, ‘(he) had plunged into a greater one … practically a captive of the Duke of Austria. We must believe it was the finger of God.’ None of the cardinals who had previously joined him left Schaffhausen with the Pope, but wandered back to Constance, where they were met with decorous contempt.

At 7 a.m. the next day, Saturday, 30th March, an assembly, with the King and some cardinals present, attempted a final compromise. At least the Pope would not be openly accused of heresy, and perhaps further negotiations might soften the language, but on the essential affirmation of its own authority, the Council was unyielding. Moving off to the cathedral, the assembly joined the Fourth Plenary Session. It was Zabarella’s duty to read on Saturday the motion previously agreed by the national committees. The Council’s decree, known from its opening words as ‘Haec Sancta’, has been described as the most revolutionary document in medieval history. It pronounced:

This holy synod of Constance, constituting a General Council, lawfully assembled to bring about the end of the present schism and the union and reformation of the Church of God in head and members, to the praise of Almighty God in the Holy Spirit, in order that it may achieve more readily, safely, amply, and freely the union and reformation of the church of God, does hereby ordain, ratify, enact, decree, and declare the following:

Turkish view of the Nicopolis battle – Crusaders on the left, charged (mid-picture) by the Turks’ Serbian allies (Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, USA/Bridgeman WAM1881799)

The formidable King-Emperor Sigismund in late middle-age (akg-images/Erich Lessing 1-S59-A1433-C)

The Bethlehem Chapel: birthplace of the Reformation

Master Jan Hus (akg-images 1-H107-A1)

A late 15th century bird’s eye view of Constance (The Stapleton Collection/Bridgeman STC94464)

The Constance butchers displayed a wide variety of meat, including bears

The newly-elected Pope Martin processes in state through Constance

Pope John XXIII arrives in Constance, November 1414, showering money on the bystanders

Pope John’s escape in disguise

The only papal election in 1,000 years to include laymen begins with the delegates locked into the Conclave

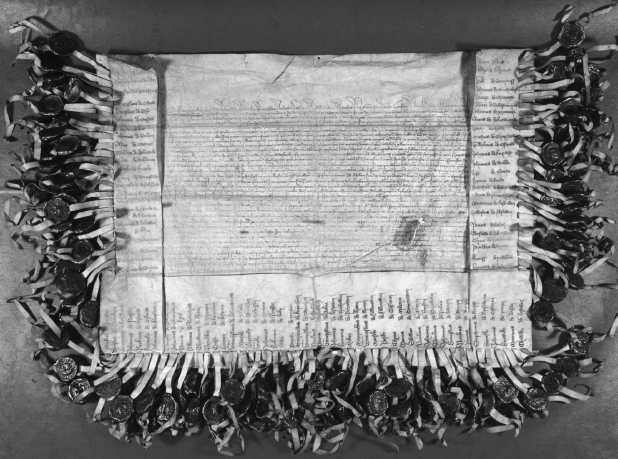

The Bohemian nobles’ defiance, with 450 seals attached. A horrid and ridiculous spectacle, according to the shocked Council (Rosgarten Museum, Germany/Bridgeman BAL52386)

The martyrdom of Jan Hus, now celebrated as the Czech Republic’s national day

The Hussite Wagenberg: an impregnable and mobile fortification (akg-images/Erich Lessing 9-1419-0-0-A3)

The impressive tomb of the first Pope John XXIII in the Baptistry of the Florence Duomo (Baptistry, Florence, Italy/Bridgeman BEN166575)

Imperia: Constance’s tribute to the Council

First, it declares that being lawfully assembled in the Holy Spirit, constituting a general council and representing the Catholic Church Militant, it has its power directly from Christ, and that all persons of whatever rank or dignity, even a Pope, are bound to obey it in matters relating to faith and the end of the schism and the general reformation of the Church of God in head and members.

When the Cardinal reached the last few words, relating to the reformation of the Church, he paused, omitting those words and the next article, saying that he considered this section not to be legally correct. A storm of protest broke out; it was for the Council – the nations themselves – not a Cardinal, however distinguished, to decide, and the session was adjourned until the following Saturday, 6 April. The only result of Zabarella’s action was to increase the general anger against the Pope and cardinals. King Sigismund himself held a meeting with worried cardinals who pleaded for some softening of the language, especially that branding the Holy Father as a heretic. It was, after all, only three weeks since they had all knelt in reverence as the Vicar of Christ graciously bestowed the golden rose upon the King. If a Pope could be so very speedily and humiliatingly disposed of, what was the future of established authority? It was unavailing. What had been read was radical enough, enshrining Gerson’s ideal of all Christian people uniting to heal the wounds of schism, but what followed a week later was truly revolutionary. The interval had not changed Zabarella’s mind and the new resolution was read by the Polish King’s representative, Andreas Lascaris. At the Fifth General Session the missing words were restored and the next article considerably strengthened to read:

Further, it declares that any person of whatever position, rank, or dignity, even a Pope, who contumaciously refuses to obey the mandates, statutes, ordinances, or regulations enacted or to be enacted by this holy synod, or by any other general council lawfully assembled, relating to matters aforesaid or to other matters involved with them, shall, unless he repents, be subject to condign penalty and duly punished, with recourse, if necessary, to other aids of the law…

Bluntly speaking, the Council, not any Pope, was the supreme power in the Catholic Church and Pope John’s removal was certain. The real danger that a successful escape by John might perpetuate the schism had been avoided by Sigismund’s quick reaction and the immediate acceptance of his authority by the princes of the Empire.

John was now on the run again. On 9 April he had left Schaffhausen with six men to trek across the Black Forest to arrive at Freiburg, a substantial town of Duke Frederick’s. There he could be reasonably secure, and renew plans to join the Duke of Burgundy. He sketched out new conditions for abdicating: Cardinal Legate for all Italy, a guaranteed income of 30,000 florins, and an amnesty for all his actions, past or future. On 13 April the Council received these proposals only to dismiss them out of hand.

The Sixth General Session on 17 April defined the terms under which John’s abdication was to be prepared and appointed a committee to ensure his compliance, failing which ‘proceedings will be started against him as law and reason dictates, as against a notorious promoter of schism, suspected of heresy’. The mention of ‘reason’ as well as law indicates how far the Council had moved from abstraction to a pragmatic realization that extraordinary circumstances demanded radical measures. A delegation, headed again by Fillastre and Zabarella, was sent to instruct Pope John bluntly to resign within twelve days, if not at Constance in Ulm or Basel, failing which he would be deposed. They arrived in Freiburg on the 21st to find, once again, the Pope had flitted. Sigismund’s assault had been devastating to Frederick. The Swiss had captured four towns and the family seat of Habsburg. The city of Baden was besieged, and a formidable field army was advancing. Duke John of Burgundy had also indignantly denied that he ever had any intention of helping Pope John, but Baldassare Cossa did not give up easily. Freiburg was now a trap, and he left on the 20th for the small town of Breisach.

The delegation despatched from Constance on the 19th found the Pope at Breisach on the 23rd in a local hostelry. Only after a good deal of prevarication by his attendants, who denied any knowledge of the Pope’s whereabouts, and after being kept waiting until the following day, were they admitted to hear John’s latest excuses. He now had no intention of returning to Constance, in spite of his previous assurances, but was to join the Duke of Burgundy who was waiting beyond the Rhine with an escort of a thousand horse. In a private meeting the cardinals urged him to abdicate, but in the morning of the 25th they found that John had once more absconded, this time to Neuenberg, alone and on foot. There he was met by the Duke of Austria’s men, mounted on a small black horse, and with borrowed clothes, returned to Breisach. They arrived in the early morning after being made to wait for an hour and a half before a gate was opened for them. John was exhausted and sobbed uncontrollably, but his powers of recuperation were astonishing.

On the 28th the deputation had another meeting with the Pope, and resumed their attempt to persuade John to abdicate. The Bishop of Carcassonne was particularly active, arguing strenuously, attempting to convince the Pope that the only alternative to abdication was disgrace and deposition. John continued to wriggle; the Duke of Austria must be pardoned; for his own part he demanded that he should be the senior cardinal, legate and perpetual vicar with full authority over Italy, and that he would abdicate only in some place where he would be guaranteed freedom. It was all thoroughly unrealistic, and the deputation cannot have had much hope that Pope John’s conditions would be accepted in Constance.

Deposing the Vicar of Christ

The Pope and Duke Frederick were now nothing more than fugitives. At Breisach Duke Louis of Bavaria caught up with Frederick, and warned him that Sigismund was intent on his complete destruction. The war had already lost Frederick much of his land and cities in the west, and the Tyrol was threatened. The Swiss had taken Winterthur, the Tyrolean barons snatched some ducal lands, and even his scattered fiefs in Alsace had been ransacked by the Count Palatine. On the 27th the Duke finally abandoned the Pope, leaving him a prisoner of the Bürgermeister of Freiburg. Sigismund had crushed his forces in only a month. He crept back into Constance on the 30th to beg Sigismund’s forgiveness, and was told ‘No crime is forgiven until the thief brings back what he stole’ – the object in question being Pope John. Leaving the Pope under strict guard – twelve by day and twenty-four at night – in Freiburg, Fillastre’s deputation left for Constance on the 29th where they found that a plenary session had already been called.

The Pope’s offer of conditional abdication was read. Fillastre recorded ‘the King would have none of that. The deputies said nothing but seemed utterly scornful and indifferent.’ The Council went straight on with indicting John to appear to answer charges of heresy, simony and many other offences. The cardinals were given copies of the indictment only as they entered the cathedral. Fillastre complained that this was now common practice. After the nations had decided the documents were shown to the cardinals ‘but for so hasty and brief a glimpse that it was not in their power to discuss them adequately. In fact the cardinals were treated with complete contempt.’ It was not fair, he reiterated, that so small a national delegation as the English, who numbered fewer than twenty persons, of whom only three were prelates, should have a quarter of the whole Council while the equally numerous College of Cardinals was neglected. It was the unhappy cry of the medieval Church against the newly empowered nationalism, and was duly ignored.

On Thursday 2 May the Council held its Seventh General Session and condemned Pope John as a heretic, summoning him to answer to the charges. On the 4th, at the Eighth General Session of the Council, papal affairs took second place to the condemnation of all forty-five of Wycliff’s assertions as heretical. On the 5th Duke Louis of Bavaria led the repentant Frederick of Austria into a gathering in the Franciscan monastery to beg Sigismund’s forgiveness, promising to ensure the Pope’s return. Richental was there, reporting that Sigismund was standing in a corner with his back to the door when Duke Frederick was brought in escorted by Louis and Burgraf Frederick of Nuremberg, to make his submission, and to guarantee that Pope John would be brought back to Constance by Thursday next. All the Duke’s Rhineland possessions were forfeited, and the Duke nicknamed ‘Empty Pockets’. When the Duke Frederick finished his submission the King turned to the attendant lords and looked at them as if to say: ‘See how mighty a prince I am over all lords and cities.’ Sigismund had convincingly demonstrated his Imperial power in a way that had not been exercised for a century, and was rarely to be repeated.

The neatest way to dispose constitutionally of an unwanted Pope would have been to decide he had never been a lawful pontiff, the method adopted by the opponents of Urban. With John it was more difficult, since everyone concerned in the Council, which he had summoned, opened and presided over, had accepted him as the undoubted Pope. He could be discredited by heaping criminal accusations on him, but that could be applied to many of his predecessors and would make an uncomfortable precedent for his successors. In the end both methods were chosen.

The quickest method was implemented first. On Monday 13 May the Ninth General Session was told that Pope John had appointed three cardinals – d’Ailly, Fillastre and Zabarella – to act for him, which they had declined to do. A long argument followed as to who should fix the notice summoning John to trial to the doors of the cathedral. It was, after all, the first time that a pope had been put on trial and the protocol was uncertain. More usefully, a committee was charged to collect evidence and examine witnesses against the Pope: witnesses who knew perfectly well what they were expected to say. The very next morning the committee was ready to report. The evidence was too copious, but Fillastre summarized it as

amounting to proof of the notorious fact that lord Pope John XXIII had administered the papacy disgracefully, dishonourably, and scandalously, particularly as regarded the making of provisions for churches, monasteries, priories, dignities and other benefices and grants of favour, expectancies, prerogatives, dispensations, and the like. All such functions he had exercised, as he did most things, in sordid ways, in return for money in vast quantities, appointing to each benefice whoever offered him most, whether by explicit bargain or in indefinite sums, before the provision was granted. He still had his gang of go-betweens and assistants, merchants and money-changers, who wielded more influence in these affairs than cardinals and men of honour. Many of them were his own familiars. Almost every thing he owned was for sale.

On the 17th John’s guards took him to Radolfzell, some ten miles off on the north bank of the Rhine, where his new custodians – one from each nation, Master John Fyton being the English representative – took charge of the soon-to-be ex-Pope. The Bishop of Toulon in a ‘fine severe speech’ told his prisoner of the charges brought against him, warned that he was now suspended and must surrender the seals of office. Finally, that he had been appointed as John’s guardian ‘and proposed to give him good company’. The fight had now gone out of Baldassare Cossa, the veteran condottiere, who handed over the papal seal and St Peter’s ring, and only begged, in tears, to be allowed to keep his personal attendants. ‘At length out of pity and for the honour of the Roman Church’ his guardians accorded their prisoner this last favour.

On the 25th, at the Eleventh General Session, the prepared indictment of seventy-two articles was considered. Some of these could not be contested – like almost all his predecessors, John had been guilty of the grave sin of simony, to which could be added a fair amount of violence and tyranny, again not entirely peculiar to John’s period of office. The indictment gave Edward Gibbon the opening for one of his best jokes: ‘the most scandalous charges were suppressed; and the vicar of Christ was only accused of piracy, murder, rape, sodomy, and incest’. Gibbon was, however, being less than honest and the truth was less entertaining. The two major suppressed charges, heresy and plotting the death of Pope Alexander V, admitted doubt. The fifty-four accusations that were published were a very mixed lot, ranging from the ludicrous accusation of dressing in layman’s clothes in order to escape to gross maladministration; two specifically related to a dubious contract with a merchant in Flanders; some were general complaints of the Pope’s behaving more as a sportsman or soldier than a prelate; others concerned his attempt to escape from the Council. The most serious charges were financial, falling under the general head of simony – the sale of ecclesiastical offices. John had certainly been guilty of these but no more than many, indeed most, of his predecessors. Then, all Pope John XXIII’s alleged crimes and misdemeanours had been well enough known for some years; only ten weeks before the indictment was prepared, kings, dukes and cardinals had knelt before the man they accepted as the Supreme Pontiff. What had since turned the scales had been the Pope’s escape and the attempt to perpetuate the schism. Christendom had suffered from the division for too long for anyone now to rally to Pope John.

The deposition was formalized on 29 May: the papal seal was smashed by a goldsmith, and all Christians released from their obedience to Baldassare Cossa, who was sentenced to remain a prisoner of King Sigismund. A rider was also added to the sentence that neither Angelo Correr (Gregory) nor Pedro de Luna (Benedict) should in future be chosen to be pope.

Skating over this last requirement, and moving on to the second solution to the papal problem, the Council began negotiations with Carlo Malatesta, Prince of Rimini, who had been given complete and unequivocal powers to act on behalf of Pope Gregory, and was determined to get the best deal he could for his old friend. Negotiations were therefore protracted. The solution eventually arrived at was complex and demanded a suspension of disbelief. Sigismund presided, at the Fourteenth General Session of the Council on 4 July 1415, in full Imperial robes, the counterpart of the Emperors of Byzantium, a crimson silk dalmatic and cape, the golden Imperial Crown, sceptre, orb and sword of state. The ‘most holy lord Pope Gregory XII’ was once more, in his absence, acknowledged as having been all along the true head of Christ’s Church on earth, represented by Prince Carlo, who read out two Bulls giving him powers to authorize the Council, and to appoint Friar John Dominici, now welcomed by his colleagues as Cardinal of Ragusa, as his deputy. The Cardinal then announced that Gregory authorized all future acts of the Council and that the Pope would now abdicate and in compensation be rewarded with recognition as senior Cardinal, second only to the Pope, and the appointment for life as Legate of the March of Ancona. The cardinals accepted the deal reluctantly, casting doubt as it did on their own past conduct, but Fillastre proclaimed Tuesday to have been a ‘happy and famous’ day indeed. If Benedict’s claims were neglected, the schism was now ended. It was an obvious fiction, but it worked well enough to allow the Council to continue.

Minor Matters

The major items of the Council’s agenda were now the Emperor’s journey to Perpignan in order to obtain Benedict’s resignation, and to England and France to reconcile the two nations and enable a new Crusade against the Turks to be called. What appeared to be quite minor issues, however, remained to be settled: the cases of Jan Hus and Jean Petit.

The Jean Petit case was regarded as the more important, and remained a cause célèbre for many years. The murder of Louis Duke of Orléans had been justified, at the behest of the guilty Duke John of Burgundy, by a Paris professor Jean Petit as ‘tyrannicide’. Petit’s assertion was attacked by the new Duke of Orléans, Charles, by Count Bernard of Armagnac and also condemned by the University of Paris. Duke John hoped that this decree could be reversed by the highest possible tribunal, the Council at Constance, and his emissaries were instructed to ensure that this was done. To help things along Pierre Cauchon, the head of the Burgundian delegation, was secretly sent eight vats of the best Burgundy ‘pour cellui vin donner et faire presente de par nous a plusier cardinaux &c. pour avoir nos faiz pour plus recomandes’. After a great deal of discussion, the wine did its work; tyrannicide was generally deplored, but Petit’s name was not mentioned and the dispute continued until in September 1419 Duke John was himself murdered by the Armagnac faction: an elegant and decisive conclusion.

The trial and sentencing of Jan Hus has had such tremendous consequences that historians have discussed the events in great detail, at least over the last 300 years or so, the Protestants indignantly and the Catholics generally apologetically. Hus became the first ‘Protestant’ martyr, and is usually regarded as the founder of Czech nationality: 6 July, the national festival of the Czech Republic, Master Jan Hus Day, is the anniversary of his execution at Constance. At the time, however, the consequences could hardly have been foreseen. A speedy solution to the Hus case was a political necessity. Deposing the Holy Father was a risky procedure, fraught with potential dangers; it had taken all Sigismund’s persistence to force the dissidents into line. The dramatic exposure of a heretic would demonstrate the orthodoxy of the Council – and there was no doubt in anyone’s mind that the outcome would be a condemnation. The only question was whether Hus would back down and recant, or whether he should be burned alive.

On 20 March Hus had been transferred to a dungeon in Gottlieben castle, where he was held incommunicado under miserable conditions, permanently chained. The cardinals appointed on 6 April to examine the charges against Hus found themselves too busy, and delegated the work to subordinates. On 18 May the Council received an appeal from Bohemian and Polish nobles attesting Hus’s orthodoxy and demanding a public hearing: at a private hearing Sigismund was clearly embarrassed by the potential conflict between Council business and his personal responsibilities. The Bohemians also offered themselves as hostage for Hus. The official answer, however, by the Patriarch of Antioch, betrayed the monocular vision of the hierarchy: if Hus was innocent, he would be given the opportunity to refute the charges, but so wicked and untrustworthy a person could not be allowed freedom, even if a thousand nobles were to guarantee him.

Twentieth-century organizers of show trials could have improved the Council’s performance in some respects: although Hus had been kept in prison, and appeared at his trial ill and weak, he had for a time been allowed to see his friends and – more dangerously – to have his letters circulated. These, and their answers, were of course read and the information passed on to Hus’s prosecutors, who thereby gained one very useful weapon. Jacobek of Střibo, the most active and radical of Hus’s friends, had already begun a campaign for communion in both kinds – the administration of both the bread and the wine to all communicants at the Eucharist – and wrote to Hus urging that he should advocate this. While sympathizing with the principle, Hus appreciated that this was a dangerous issue. The demand was in no way heretical or unorthodox: the privilege given to the clergy of being the only ones allowed to take the wine was relatively recent – only formulated in the thirteenth century – was not enshrined in canon law and was indeed specifically contrary to the original command of Christ. It was, however, valuable in marking any priest as superior to any layman, and thereby reinforcing the power of the hierarchy, and proved another useful challenge to Hus’s orthodoxy.

The confrontation with Hus began on 3 June immediately after the deposition of Pope John, indicating the urgent need for the Council to demonstrate their commitment to orthodox doctrine after their revolutionary decisions. Hus was brought from his prison in Gottlieben on the 5th in chains, to an examination in the refectory of the Franciscan convent. The first session, at which Sigismund was not present, also began in Hus’s absence. Hus’s allies Václav of Duba and Jan of Chlum were alerted by Peter Mladoňovic, and protested to Sigismund, who ordered that Hus must be present. He was, however, merely shouted down, and the meeting ended in tumult, adjourned to Friday the 7th. At that subsequent meeting Hus was accused of agreeing with the already condemned and much execrated Wycliff, the Oxford doctor John Stokes being particularly aggressive, presumably attempting to defend his university’s reputation. The proceedings that day, and on the Saturday, were largely technical matters, some charges intelligible only to the more subtle theologians: was it, for example, really heretical to state that St Paul was not a limb of the Devil? Apparently it was. Without becoming entrapped in detail, the debate centred around the nature of the Church. To Hus, it was the community of all true believers who sincerely attempted to follow the commands of the scriptures. To his accusers, it was the formal structure of the Church, rather drastically modified by their very recent decision that the Council, rather than a pope, was the supreme authority. Hus insisted that all, pope or priest, had to be virtuous; the cardinals insisted the legality was all-important. John had been deposed because simony was a legal disqualification, buggery merely a sin.

D’Ailly advised Hus to submit to the Council’s decision, when he would then be treated with piety and humanity (which probably equated with permanent imprisonment), but that if he insisted he would be given another opportunity to defend himself. This promise was never kept, and Hus was left with the choice between denying all his previous beliefs, and therefore betraying all his supporters at home, or death. Sigismund, who recognized a potential embarrassment when he met it, would much have preferred Hus to submit, as would most of his accusers. An ignominious surrender would prove the authority and orthodoxy of the Council much more than a steadfast refusal. On 5 July Hus was brought before a committee of prelates and offered some reduction in the charges, and on the same day Sigismund sent Jan of Chlum and Václav of Duba in an attempt to persuade him, but the Lord of Chlum’s advice was that his master must follow his conscience, and Hus stood firm.