It had been two months since I’d left the States. It seemed much, much longer. It would be another two months before I could go on my mid-tour R&R break in November—still a long time away.

Decarli returned for a follow-up regarding his anger toward his immediate superior. He reported feeling slightly less animosity toward this individual. “The best way I’ve found is to avoid him,” he said. “He goes one way, I’ll go another.”

We discussed Decarli’s history of anger problems, where he learned this behavior, and how he could unlearn it: by replacing the behavior with a healthier way, such as taking deep breaths to remain calm, “Focus on your breath because it’s in the present—you can’t breathe in the past or in future,” and not allowing others to dictate his emotions. The sergeant found talking helpful and was willing to practice new skills.

After Decarli left, I wrote to a couple of more companies asking for donations: Kimberly-Clark for Kleenex, Pampers for baby wipes. Who knows? They can only say yes or no. I also helped the PX manager request Xbox games and television sets.

Cunningham returned in the afternoon. He was still experiencing nightmares, but with the tapping he was able to get back to sleep. We worked on being more specific about the nightmare so that we could collapse it further with the tapping.

“Even though I can’t forget that I dishonored the dead, it wasn’t right, I was doing my job, I deeply and completely accept myself.”

Afterward, he shuddered as he said, “I tried to get the dead detainee’s fingerprint. I tried so hard that I broke the knuckle. The body was in rigor mortis.”

Cunningham felt guilty and shameful. “It’s wrong for me to violate the body. Even though they were insurgents, it’s wrong.”

We tapped on, “Even though I could hear the sound, the feeling of breaking the knuckle, I accept myself. Perhaps I can forgive myself.”

Staring off at nothing, with a heavy sigh, he said, “I think all humans should be laid to rest without any more harm…” He was a deeply feeling man.

Later the aid station referred Staff Sgt. Young because of daily panic attacks he had been experiencing in the previous week and a half. Although he was on medication, it hadn’t helped. He spoke in a monotone and his face was void of expression. Young had been having panic attacks since 2004, when he first returned from Iraq.

“I feel closed in. I sweat…my heart pounds. It feels like I’m dying.”

“How long does this last?” I asked.

“Maybe half an hour.”

After I gave Young an overview of EFT, we tapped for the attacks, the physical symptoms of an attack, and on future attacks.

“Even though I don’t understand why I get them, I don’t need them anymore, and I choose for my body to release them, for my body to heal, to feel peace and joy again.”

I didn’t know if the tapping was going to work this time, as I’d forgotten to ask for his starting SUD rating so couldn’t compare it to an ending SUD level. Young was cooperative, but lackluster.

The day after meeting with Young, I received a phone call requesting that we conduct a TEM (traumatic event management) at Check Point 8.1, a compound near our FOB. At nearly the same time as the August 27 VBIED attack on PSS-1, another suicide car bomb had attacked this checkpoint. There was an American casualty, one seriously wounded, resulting in that soldier being brain dead. After a week, the soldier’s family made the grim decision to take him off life support. The unit was requesting Combat Stress to come process with the soldiers affected by this tragic event. I notified my command. They had to review and approve route and transportation before we could leave CNS.

As I was waiting to hear from command about our upcoming mission to CP 8.1, the Internet went down. I figured it wasn’t a big issue. Maybe the new Internet company was working on it. But later, Maj. Stefani came into my office.

“Did you hear there was a KIA at PSS-9?”

“No, sir. What happened…where’s PSS-9?”

“Not far, about two kilometers from here. Spc. Scott dismounted from his vehicle to conduct some meet and greet with local merchants when an assassin came from behind and shot him in the back of the head.”

The Internet wasn’t working because of communication blackout.

Soon Maj. Krattiger came into our office with the grid coordinates of PSS-9 and wanted us to respond there. We forwarded the information to our unit operations officer for approval.

Much to my surprise, in the middle of all this, Young came back in. I thought he wouldn’t return.

“I had no panic attacks the day and night after our last meeting.”

“That’s great news,” I said.

“But I had one this morning. But it was less intense.”

We had made some progress. He was amazed.

“I don’t understand how it works…”

“I can provide you a scientific, medical, or holistic explanation. But do you really want to know how it works?”

He shook his head no. “I know it works…I don’t understand it, but it works.”

“Do you want to continue the sessions and figure out what might cause these panic attacks?”

He said, “Yes.”

My hypothesis was his deployment stresses in Iraq.

While we were still waiting to hear about our departure for PSS-9, Gallego returned for a follow-up. He reported better sleep since his last visit late August, but for the previous two nights, he had been waking up every 45 minutes, thinking about his family and his last tour. Recent events at work had triggered these troubling memories.

“I can’t stay motivated at work,” he said. “No one appreciates my initiative or my work mentoring soldiers. I might as well leave.”

“There are consequences to leaving,” I said. “You could lose rank and receive a dishonorable discharge. How will you support your family? It can also affect your future employment with federal jobs, too.”

He nodded that he understood.

“I know it seems like this will never end, but deployment isn’t permanent. For every day that passes, we are one day closer to going home. How about hanging in a little longer?”

“Yeah, I guess I can do it.”

“Stay in contact with your wife and children. Look for any positives.”

With a sudden lightness, he said, “Yeah, I can think of the motorboat I want…to take my kids fishing.”

After Gallego left, I found out that Maj. Michaels, who had asked for my help in writing to his wife, had flown out of Afghanistan. I learned this accidentally, by talking to his replacement. Michaels’s wife had managed to convince a physician to say she needed her husband to return home because of her poor health. It had worked!

Li and I waited the whole day for the green light to go to CP 8.1. Apparently, the hold-up was the transportation. Who would take us there and bring us back? We wouldn’t know until later. Maybe not even until the next day.

We submitted a tentative mission schedule of the dates and places so that HQ could track us, but the road safety conditions had to be verified first. Hurry up and wait—it was the army way. If everything worked out, Li and I would be gone on Monday and Tuesday on our two missions.

In the late afternoon, our command finally gave us the go signal for PSS-9. Now I had to confirm my transportation to and from CNS. I couldn’t believe how difficult and time-consuming this was. Before I went to dinner, I received confirmation for the CP 8.1 mission as well.

That night I borrowed the Green Lantern, a bad Chinese DVD copy, bad because the dialogue wasn’t in sync with the actors’ lips. It was so distracting I had to stop watching it and just listen. Kind of boring, but at least it was a diversion from the daily grind.

On Monday, September 5, I received the departure time to PSS-9 to provide psychological support on the death of Spc. Scott. But I was upset with a second lieutenant who was supposed to report the transportation schedule to me. I had waited for two hours in my office the night before, because I was told he would come by, but he didn’t. When he finally came the next day, the lieutenant knew from my stern look that I wasn’t pleased with his lateness. He mumbled it was a “miscommunication” and apologized. Finally, Li and I rode off around 1400 hours, and we were at the site in just 10 minutes.

After a briefing with the PSS-9 commanding officer, Li and I gathered with 15 soldiers in a small dining facility. There were no tables or chairs set up, just a bare room. The soldiers sat on the dusty, dirty floor, or leaned against the walls, looking down, a few quietly crying.

The group was initially reluctant to talk, but with patience and words of encouragement, everyone participated. There were two sergeants and one soldier extremely close to Scott. He had died en route to the NATO hospital at KAF. He was 21 years old, just eight days from his R&R, during which he was to marry his fiancée. Well-respected, Scott was funny, the go-to soldier of the unit.

Another young soldier was taken from us much too soon. The memorial service for Spc. Scott was scheduled for Wednesday, September 7 at CNS.

On the ride back in an MRAP vehicle, I squinted through the thick, dull windows and spotted some Afghan boys with matted hair, dirty faces and hands, some with dusty sandals, others with bare feet standing in the streets. Some waved at us; others threw rocks. I could understand why soldiers could become so angry after losing a fellow soldier. Many soldiers believed they were helping local Afghan National Police (ANP) learn how to provide better security for their city, so that people could enjoy a more peaceful life. Yet at the same time, many soldiers didn’t trust the ANP—they didn’t trust people with whom they were living. Some soldiers whispered the timing of attacks was well orchestrated, perhaps with information from ANP. Many were resigned to the fact that at the end of all this, after the US military left, the Afghan people, with their deep pride and fierce tribal loyalties, would continue their warfare.

The mission to CP 8.1 went like clockwork. A captain called in the morning and confirmed the pickup time. Li and I rode in a Stryker, a tank that was large and roomy, but hot and airless. Our predecessors never went outside the wire during the months they were at CNS because their command wouldn’t allow it. Whenever we were outside the wire, we were at risk of insurgent attacks. Fortuitously, nothing happened. We arrived in 20 minutes.

After our briefing from command about the brain-dead soldier, Li and I decided to run two groups, back-to-back: one group of 15, and one group of 16.

One soldier said, “I wished I had said good-bye to him.”

“It’s funny, he wouldn’t eat the MREs, just peanut butter and bread,” said another.

“I’ll miss his smart-ass remarks.”

“I made a promise to him to stay connected after we got back...”

Others expressed feeling empty, hollow, wishing he were still with them.

Based on their participation, tears, and anger, the debriefing helped the soldiers process their loss, begin healing, and refocus on their mission.

On September 7, Li and I attended the somber memorial service for Spc. Christopher John Scott, born November 17, 1989, and died September 3, 2011. It was depressing to acknowledge another young soldier’s death, especially as he was the second soldier killed from the company that had lost Spc. Roberts the week before.

After the service, I met with Sgt. Quinlan because his command was concerned about his ability to lead a group of soldiers outside the wire. The sergeant spoke with the slowness of a Southern accent and there was stiffness in the way he moved. For the past week, he’d had only a couple hours of sleep per night. And because of the sleep deprivation, it was difficult for him to make decisions. He was constantly worried, stressed, and depressed. He was also having nightmares, a common side effect of a malaria medication. He didn’t want to make a mistake in which soldiers might be hurt. I requested his command to allow him to stay at CNS, to rest and meet with the brigade surgeon regarding the problems with his medication. I wanted to see if having more sleep and a change in medication would help him function better. Quinlan wanted to stay in theater and complete his tour.

While I was meeting with Quinlan in the outside office, Staff Sgt. Osei came in. Standing nearly six feet tall and muscular, he reeked of cigarettes.

“I was told I had to come here before my team could leave.”

Wondering what he meant by that, I said, “Okay, can you fill out this intake form?”

Li talked with Osei in the inner office. About 10 minutes later, Li quickly rushed out of the room to the outer office and shrieked that Osei had removed his handgun from his holster. Li continued saying he was acting strange and saying strange things. She was afraid to go back in.

I went into the room. I saw that Osei had his M9 handgun in his hand.

Calmly, I said, “Hey, what’s going on?”

“I just wanted to show her how a round was placed in the chamber,” Osei stated matter-of-factly.

“Did you know you’re freaking out my behavioral health tech?”

“Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to. Hey, don’t worry. I’m not going to hurt her, or anyone.”

“Would it be okay if you give me your gun? It’s making me a little nervous.”

“Sure, I know you’re a good person, cuz you’re a captain wearing an army uniform.”

He handed me his gun without hesitation.

From my police training I knew to ask, “Do you have another weapon?”

Osei reached into his pocket and handed me his matte-black Gerber knife.

With a friendly tone, I asked, “So why are you here?”

“Well, after the memorial service I wanted to hurt an ANP because he gave me the look.”

Apparently, Osei lunged after an ANP, but his fellow soldiers pulled him back before he did any harm.

“So what did you learn from this incident?”

“I shouldn’t have walked toward him but should have run and killed him!”

Feeling a quick adrenaline spike, thinking he was psychotic, I said, “How about staying at CNS and taking a couple of days off to rest?”

“No, no…” he pleaded. “You can’t take me away from my soldiers. My soldiers are nothing without me, cuz I’m the Ghost Rider.”

Meanwhile, Li had contacted Maj. Stefani, the brigade surgeon. When the major came in, I told him that Osei wanted to return to his unit, but he wasn’t mentally fit. After the major met with Osei, he told me that he wanted Osei to go to KAF for observation and evaluation. I agreed, but knew Osei probably wouldn’t be willing to go.

When it was time for Maj. Stefani to tell him, Osei gritted his teeth, gripped his chair seat, and uttered, “I am trying really hard to keep my cool!” Everyone in the room was afraid he was going to be violent. Fortunately, Osei had enough respect and training to obey his superiors. He stomped out angrily but peacefully. Eventually, he was medically evacuated to KAF, to Germany, and subsequently to the US.

After this incident, I flashed back to my police training. Why did I become a police officer?

I thought about what happened when I returned home after nearly a year in France. I competed in the US Fencing Nationals in Florida and was eliminated earlier than I hoped. I was devastated, after all my training and experience in Europe. I couldn’t adjust to the slower tempo of American fencers and I was making actions that my opponents couldn’t or wouldn’t respond to. I was so upset that I quit fencing for nearly two years.

It was time to find another adventure. I needed a job, but social work positions were limited because Proposition 13 had eliminated many city and county jobs in California. The San Francisco Police Department was hiring, however, after a long court battle that forced the city into hiring more minorities and females. I took the written exam and scored well enough to be in the first group of the civil service list. The physical exam wasn’t too difficult, since I was still in good physical shape and had practiced the dummy drag on Rob many times. What I was most worried about was my weight. For my height, 5 foot 3.5 inches, I was supposed to be 110 pounds. But I was only 99.5 pounds, no matter how many banana shakes I drank before the medical exam. Fortunately, the city’s physician asked if I was always on the light side, as he could tell I was fit. I passed the vision and background checks, and I went into the Police Academy on November 13, 1979, as a member of the 133rd recruit class.

A month after entering the police academy, Rob proposed to me. By this time, even though Rob loved fencing, it was time for a career change for him. Prior to the wedding, Rob was completing prerequisite courses in bio and organic chemistry before starting chiropractic college. Rob was a believer in holistic medicine and, as a patient of chiropractic care for several years, Rob knew firsthand the benefits of this alternative approach. We wed in July. With me being 27 years old and the last daughter to get married, I think my parents were just happy someone wanted me, even if he wasn’t a Chinese man.

After the field training, I patrolled in uniform on the midnight watch in the city’s Richmond District. The department was so thin in personnel that I was a solo unit from time to time. Having a partner was safer and helped pass the time. Patrolling was excruciatingly boring. Even the dispatcher had nothing to say after four in the morning. Occasionally, I would respond to a bar fight, domestic violence call, or burglary or arrest drunk drivers. But most nights I would drive around the district citing vehicles with expired registration tabs just to pass the time. I was going brain dead. I considered resigning after 10 months in the department. But one day my sergeant said I was transferred to the Street Crimes Unit in the Tactical Division. My name had come up for this specialized unit, which I had signed up for after I completed my probation. I didn’t know what the new job entailed, but this was a chance to get off midnights and to work the day shift.

The morning I walked into the Tactical Division, the lieutenant laughed and said, “You look like a victim to me.” What did he mean by that? What had I gotten myself into?

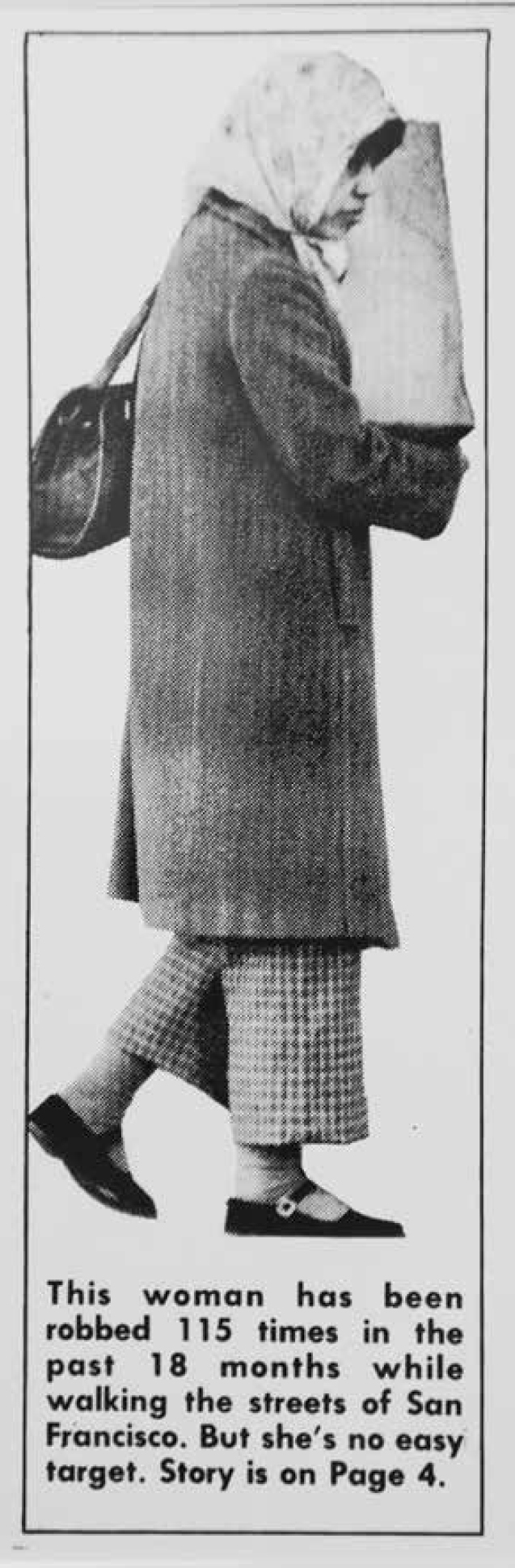

The lieutenant told us that the Street Crimes Unit was starting up again to arrest and to deter pickpockets and purse-snatchers in high crime areas of the city. There were four black male police officers, a white female officer, and me. My role was to look and act like a victim, essentially inviting would-be bad guys to separate me from my valuables. I learned to put on make-up of facial bruises, put my arm in a sling, walk with my eyes cast downward—fundamentally everything opposite to a self-assured police officer. At times, I dressed in my mother’s old coat and scarf, shuffled along the streets with my purse over my shoulder, and waited for someone to take it. Other times, I wore a gray Mickey Mouse sweatshirt and carried a camera. This wasn’t entrapment. Entrapment required a police officer to put the idea of committing a crime into the suspect’s head. There was never any verbal exchange between the decoy and suspect.

I admit at times it was scary being the decoy. I wore an earpiece so I could hear when possible suspects were approaching me. My heart would pound. I couldn’t transmit if something went wrong, nor could I carry my service revolver, because it was too large and bulky under my clothes. Sometimes I was on the back-up team to arrest suspects when others were the decoys. My lieutenant, a six-foot-two white male, was a great decoy. This part was dangerous, as suspects don’t want to give up their prize or go to jail. Often they tried to run, fight, or even use weapons. I had my share of rumbles in the streets because suspects often didn’t believe I was a police officer. I was in plain clothes, Asian, and slightly built, and showing my police star didn’t matter; they were going to fight. Overall, the work was exciting and satisfying. We were able to put many career criminals behind bars through this process.

Author as police decoy. Source: San Francisco Chronicle, February 1983; photo by Frederic Larson.