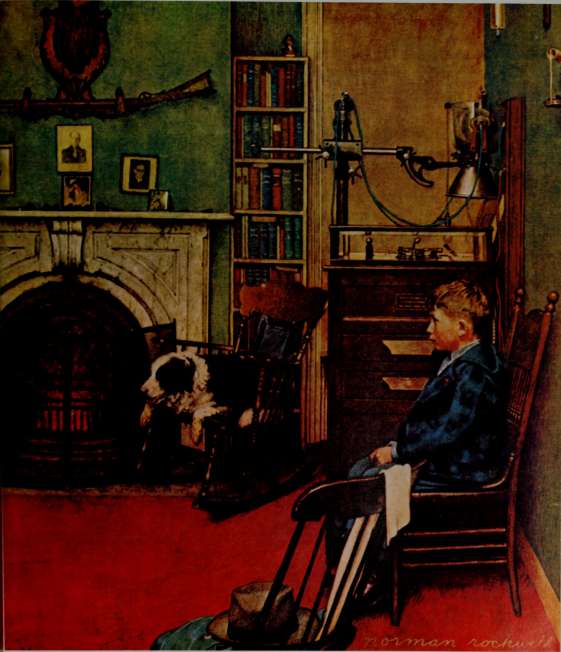

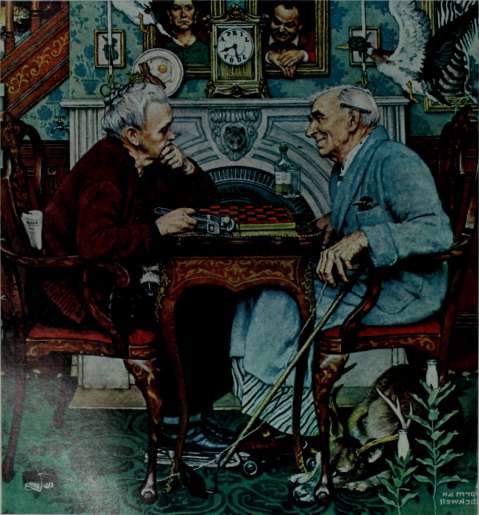

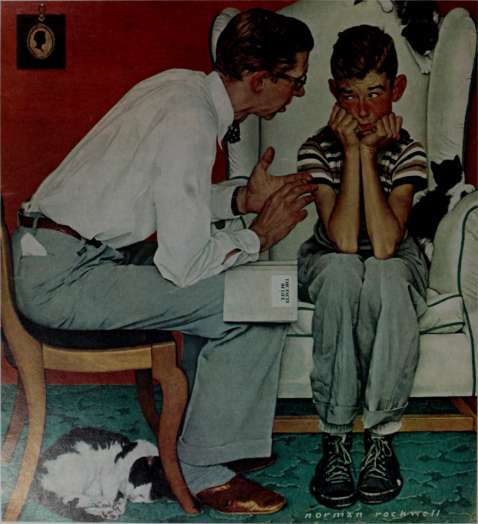

The Family Doctor (1947)

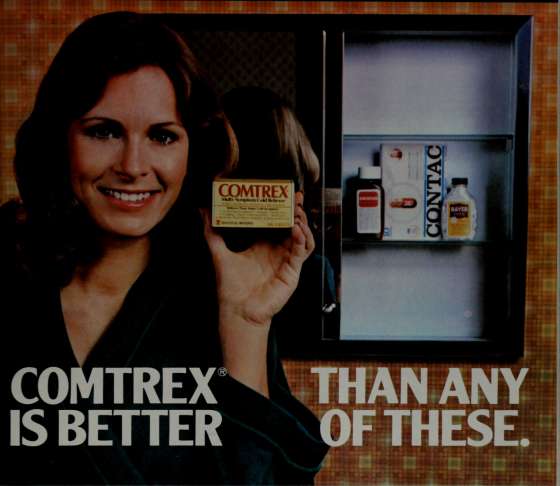

For relief of these multiple cold symptoms-nasal and sinus congestion, runny nose, aches, pains, fever and coughs...

OOMTREX

MuW-Syinptom ColdReiever

Rrfincs Thr«c Mjfor CoUSympCoim

1 fc#invN€Ji^

The ingredients in Comtrex make it better than Dristan, Contac or Bayer in relieving this complete combination of cold symptoms: 1. nasal and sinus congestion, 2. sneezing, 3. runny nose, 4. coughing, 5. fever, 6. post nasal drip, 7. watery eyes, 8. minor sore throat pain, 9. headache, and 10. body aches and pains.

AlI by itself, Comtrex gives more kinds of relief than Dristan or Contac or Bayer. Because only Comtrex has a cough suppressant.

^j^s^ ^^ So, the ingredients in Comtrex make it better in <:^^^^'^ i^'t/ Cr relieving this complete combination of symptoms.

Try Comtrex from Bristol-Myers.

i!>^

Available in tablet or liquid.

COMTREX'

Multi-Symptom Cold Reliever

)1979 Bristol-Myers Co.

m?^^

.«.3 ., r -:■■:

^■?*.^i,;, •;^.=«e:.

..::m^i^^^U

New Handle With Care' oes More Than Woolile:

ir«

Cleans body soils better.

Has a special fabric softener.

Stops static cling.

Works safely in hand or machine wash.

Suds rinse out easier when you hand wash.

Designer fashions by vcjniry Fair

(Peignoir Set).

Tennis lody Cfennis Weor),

a<^^--

^3^S'

^^

s^

#^^

#^^

^\v\^'\

Joan Sibley (Evening \Atear

ond Suit) and

RufflnKnii (Sweater Outfit).

I

b

urfinewa

e 1978 The DracketT CorTtpony

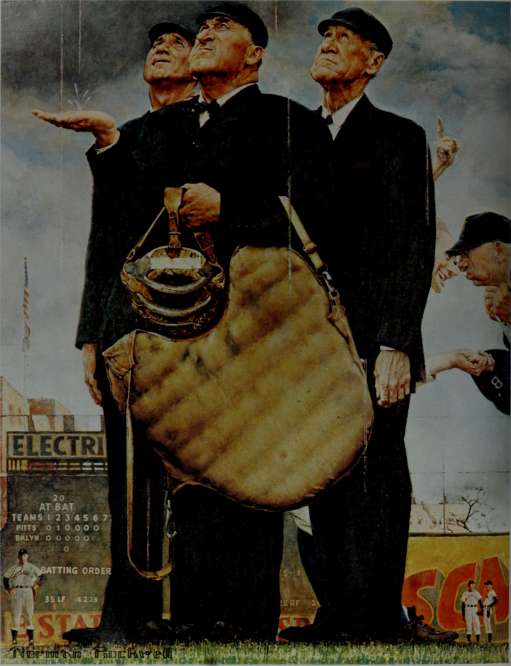

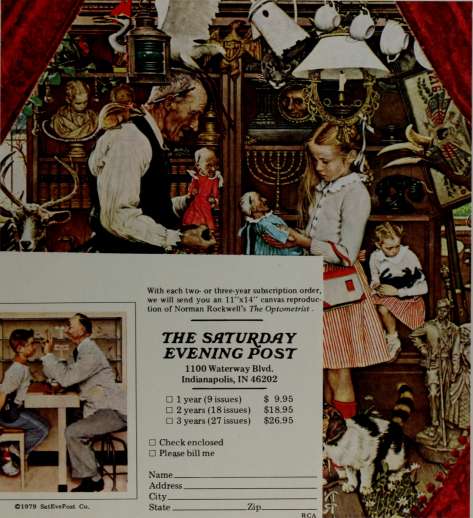

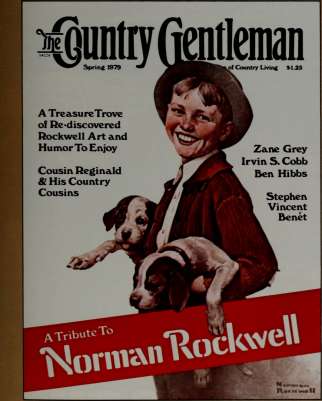

SATURDAY EVENINC POST /iLBUM

Vokimc I, No.

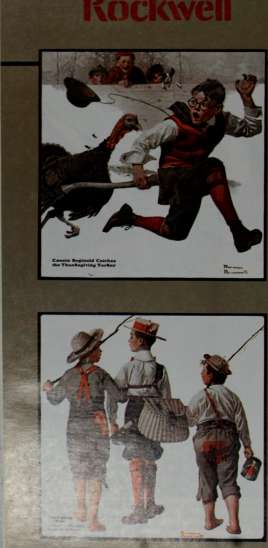

ISiorman Kodiwell Memory Album

TABLE OF CONTENTS

An Introduction to a Legend 10

April is the Foolingest Month 12

What You See is What They Saw 20

The Illustrator Draws Breath 28

Favorite Themes: Losers, Music, Love 34

Daniel Webster and the Ides of March 50

Tlie Rockwell Visits 54

The Narrative Element in Painting 60

Famous Faces 66

Rockwell Paints Rockwell 70

Parade of Hits 74

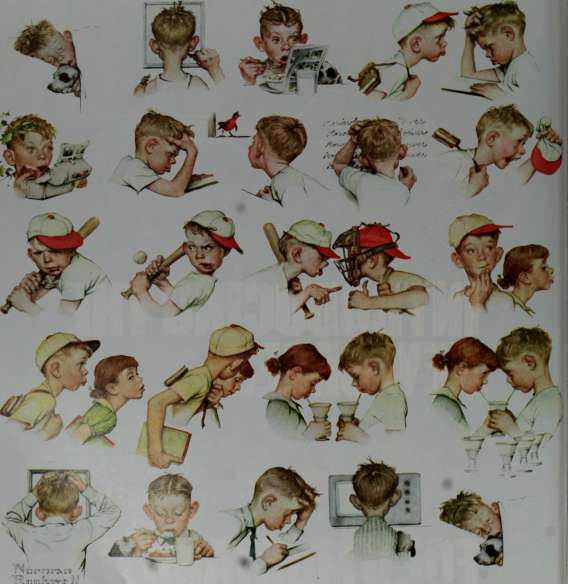

RockweU's Wonderful Kids 86

The Norman Conquest 90

The "Other" RockweU 106

The Times They Were a-Changin' 108

Jeff Raleigh's Piano Solo 114

Other Directions 116

The Artist Merits a Badge 120

The Inside Story 130

Old Favorites to Frame 136

NORMAN ROCKWELL MEMORY ALBUM STAFF

Starkey Flythe, Jr., Editor Jean White, Associate Editor Jinny Sauer Hoffman, Art Director Kay Douglas, Kathleen Saunders, Patricia Stopa, Art Editors Robyn Kimble, Copy Fxlitor

THE SATURDAY EVENING POST

Cory SerVaas, M.D., Editor & Publisher

Frederic A. Birmingham, Associate Editor & Publisher

Don Moldroski, Art Director

Dwight Lamb, Production

THE CURTIS PUBLISHING COMPANY

I 100 Waterway Blvd., Indianapolis, Indiana 46202

SATI'KDAYKVRNINUrasT ALBUM.SUMMER. 1979

Vokimc I. No I

Capjiif)\l O tilt The Silurdar Kyenini; Port Company, I 100 Waterway Blvd.. Indianapolis. Indiana 4«202. All righlj rcscryed. Published quarterly. Saturday Eveninf Port Album editorial.

I<uufma, and rircuUlion onVei arc located at I 100 Waterway Blvd.. Indianapolis. Indiana 46202. SUBSCRIPTION PRICKS: U.S- and Possesions; One year. SI2.00. All other countries:

JI5.O0 W)STMASTf:l' Send Form 3S79 to Saturday Evening Port Album Subscription OfTKes. P.O. Bos 1144, Indianapolis, Indiana 46206. CHANGE OE ADDRESS: With service

adjustment fr^"»'^i

■ hi

nd f.-ilcst mailing labels, inchiding those from duplicate copies, to Saturday Evening Post Album Subscription Offices. P.O. Box 1 144. Indianapolis, Indiana 46202. Allow ' < h«nv.c uf address. Application to mail at second-class postage rates is pending at Indianapolis, Indiana. Unsolicited manuscripts, arlwork, and photographs M:4f; POST ALBUM must be accompanied by an addressed return envelope and the iMCnsary portage. The publisher assumes no responsibility for the return of ■ ►. -i' photographs. The names of characters used in all SATURDAY EVENING POST ALBUM Ticlion and seminction articles are Tictitious. Any resembUnce to a

Vihmrited unaohcilr.j

hving peiuj.i

l*oln crcdtti t jgea 1», 40, and 42. Betlman Archives; page 106. Brown Brothers; pages 108. 109, I 10. and I 12. Bettman Archives; page I 12, Bettman/Springer. The illustrations on pages 48. 49. 52, S3, 87, ^9. 96, 97. 137, (29, and 133 of otherwise not credited are the copyrighted profierty of The Curtis Publishing Company and cannot be reproduced without permission, (■nnled by f awoett Printing C'H-poration.

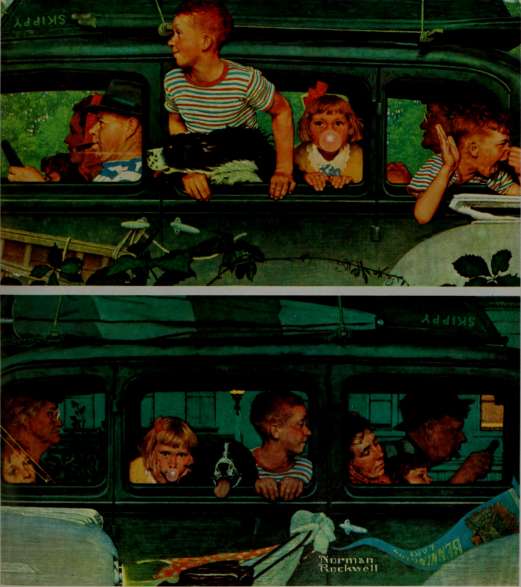

Ifs HatdTb Beat Skimpy

Because:

"It's high in protein and it has no cholesterol."

"It's very nutritious and good for you."

1 love the way it tastes."

"When it comes to good nutrition and great taste-It's hard to beat Skippy^"

SK\PW

I

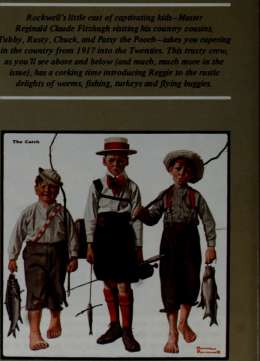

An Introduction to a Legend

If a Man^s Work and a Man's Life are Qood, his Memory is a Living Treasure the World can Share

This book is a collection of Rockwell words and Rockwell work. For the more than 65 years of his working life he painted walls, advertisements, calendars, magazine covers, portraits, story illustrations, Christmas cards, and posters. Other artists have covered the same ground, but nobody else in American illustration-or in American art—has held the mirror of the people's yearnings up to their accomplishments so closely as Norman Rockwell.

To find a similar national mirror one would have to go back to Goya in Spain or to Daumier or Toulouse Lautrec in France. Rockwell himself never encouraged such comparisons, but just as these artists speak most clearly to their own nationalities and their own times, so Rockwell speaks most eloquently to us and to our times, or to a time slightly past. Although his universality is mainly a melting pot approach, an American view, he was widely hailed abroad wherever his frequent travels took him.

His work is unpretentious and witty. Like the man. He was "scared to death," he said, every time he was called on to paint a President or a prime minister-though he must have known, in his later years, that he himself was a man of great achievement. Greater achievements than theirs? It is at least safe to say that lij, work will

be remembered and loved when the legislative accomplishments of some of the pohtical figures he portrayed have been forgotten.

He made few pronouncements about art, other than to study with the best and work hard. But

time to

time he was worried about his work, sought new styles in Paris and other art centers, and tried to overcome the sameness of form his commissions demanded. Finally, he was able to vary his style by painting a more intensely realistic approach to a moral characterization of the American people, h^ capturing a dream of pur-

pose and making it concrete. It is obvious he believed in what he painted. But he was not a preacher. He treated his more serious work Ughtly and laughed with the critics, though admitting he could be and was hurt by critical disfavor.

He put something of himself into every character he created. One man who knew him well said: "He himself is hke a gallery of Rockwell paintings-human, deeply American, varied in mood, but full, always, of the zest of living."

Like the Boy Scouts whom he painted, he was loyal and true. To the magazine of which he was as much a part as Benjamin Franklin, he gave his best. And when the Post lost its way in the 1960's and suggested it no longer needed its number one artist, Rockwell went right on working, finding new outlets, changing his subject matter to go along with new times. The quality and sincerity of his work remained. And in the twentieth century it was not equaled by any other illustrator's.

Here then is a sample of the master's work and life, some comparisons, some suggestions about where he fits in art history and popular appeal. His place in our hearts needs no exploring.

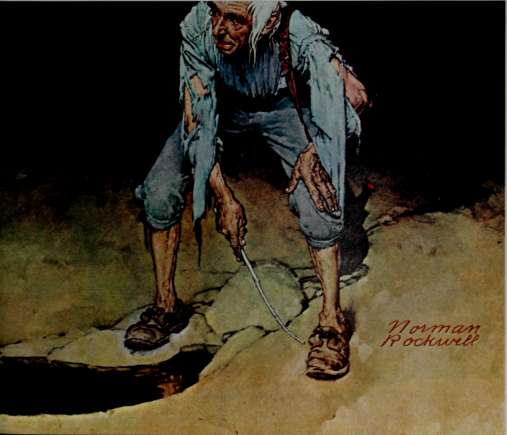

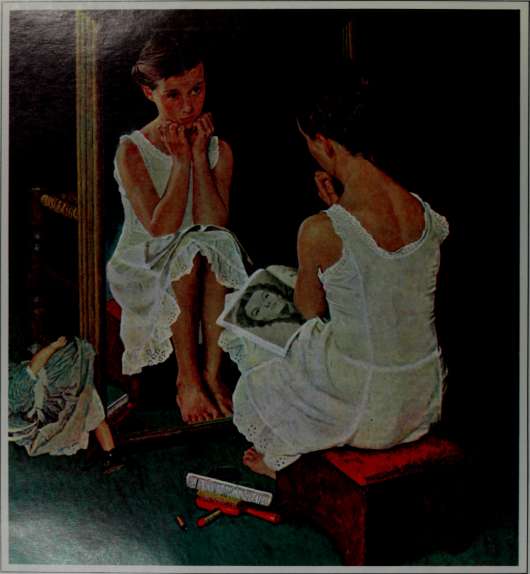

The fleeing hobo (above left) was a Rockwell whimsy of the '30's. The triumphant tomboy, in the '50 's, was another masterpiece of the storyteller supreme.

r^ mm vm

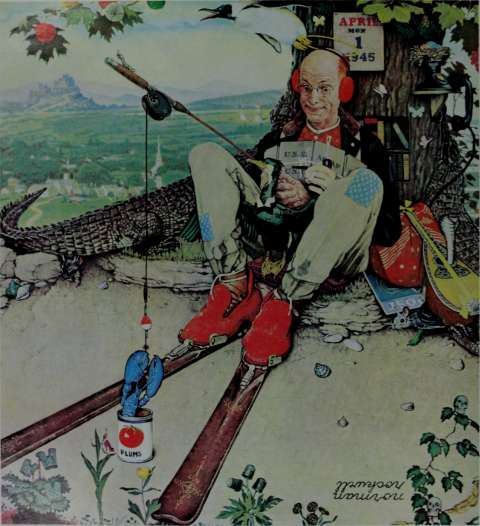

April is the Foolingest Month

How many mistakes and incongruities can you find? Possibly more than the artist intended. Rockwell said he painted 45 errors into the first of the April Fool's Day covers he painted for relaxation between serious projects; one man wrote saying he found 120.

Rockwell bought furniture for his house with an eye for using it later in illustrations. Here his house beautiful and his career in advertising, his Fish tire and his fireplace, struggle for ascendancy while the medicine bottle achieves it.

%

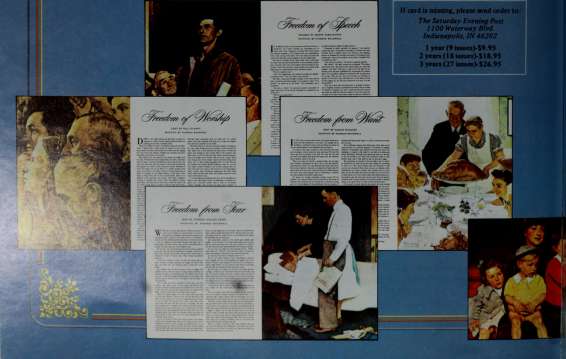

With each two- or three-year subscription order, we will send you an ll"xl4" canvas reproduc tion of Norman Rockwell's The Optometrist ■

©1979 SatEvePost Co.

THE S/lTUI{pjlY EVENING POST

1100 Waterway Blvd. Indianapolis, IN 46202

D 1 year (9 issues) $ 9.95

D 2 years (18 issues) $18.95 D 3 years (27 issues) $26.95

D Check enclosed D Please bill me

Name

Address

City

State Zip

RCA

form decidedly does not, and the typically Rockwellian dog blending into a typically Rockwellian cat may be puzzled when it tries to bite its tail

Before the acceptance of the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Day fell on March 21, the vernal equinox when the length of the day equals that of the night and spring bursts upon the world. Priests were unhappy, though, with the proximity of Easter and New Year's, festivals of gravity and frivolity. So New Year's was postponed to April 1, and, with the new calendar, moved in 1 549 to January 1.

But custom dies hard. Friends still gave presents on April first, made visits, played jokes. Often they would put trinkets in grand boxes to make them look like something expensive and laugh when friends opened the box-"April Fool!"

Ancient legend connects April with the kidnapping of the lovely Persephone by Hades, god of the underworld. Her mother, Demeter, the goddess of growing

13

Warbling native woodnotes wild bring the cobra out of its mandolin, the squirrel out of its shell, buttons and thimbles out of the ground, apples out of oak leaves, and the lobster out of his plums.

things, grieved for Persephone and the earth turned brown. Hades, at Zeus' command, gave up his beautiful captive, but only for part of the year. She came, her hair wreathed in flowers, just at spring, and all the earth rejoiced, exploding with life, turning green and fertile.

Rockwell's April Fool's covers are celebrations of the innate desire of creatures to play. ^

Dutch and Flemish painters delighted in upsetting the eye, mixing man and beast, marrying the strange with the known in their pictures. One senses the same attitude of enjoyment in the Rockwell puzzle-paintings. They were a sort of answer to people who complained about mistakes in his serious covers. But more, they were an expression of fun and love for the absurdity of man and his possessions.

I

Norman Rockwell

and Ford Motor Company

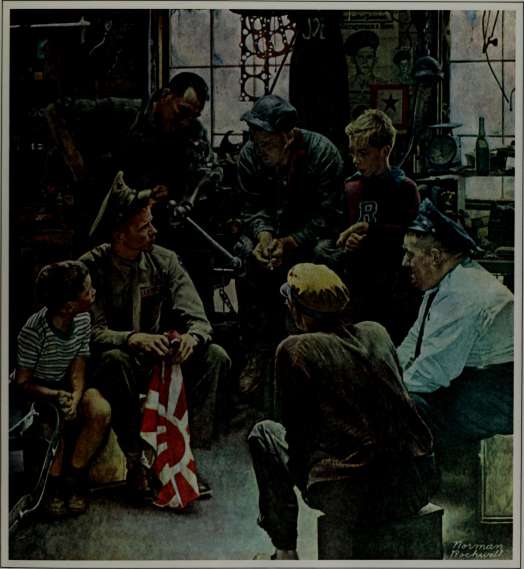

A quarter of a century ago, in commemoration of its 50th Anniversary, Ford Motor Company ran a series of advertisements with the theme ^'50 Years of Progress on the American Road". The most memorable advertisements in this series were those which were illustrated by Norman Rockwell.

Ford Motor Company is pleased to present two of these advertisements in this Norman Rockwell Memorial Album. We believe that Rockwell's art is as warm, human, and meaningful today as it was when these illustrations were created. And we also believe that the message conveyed by these advertisements from 1953 is equally significant today.

^JrcC

..^cs^^ia^THE AMERICAN ROAD—XIV.

The boy who put the world on wheels

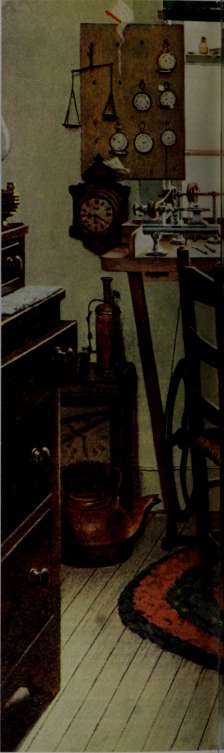

The boy was ten years old, slim as a buggy-whip and quick as a cricket. He had a passion for machinery. He tinkered with all the clocks in the old white clapboard farmhouse until they tock-tocked the right time.

One Sunday morning, after church, a neighbor took out his big gold hunting-case watch. He said: "Henry, can you fix my old turnip?" The boy found that a jewel was loose in the works; he joggled it back into place and the watch ran.

The neighbors around Dearborn ,began to bring him their ailing timepieces. So young Henry Ford set up shop on a shelf in his bedroom, working nights after chores—in the spring to the fragrance of the farmyard lilacs, in the winter keeping warm with an oil lantern between his feet.

He ground a shingle nail down into a tiny screwdriver, made tweezers from his mother's corset-stays, and little files from knitting needles. All his life he tinkered watches, and never had to use a jeweler's eyeglass.

For he could almost see with his long thin steel-sprung fingers—the fingers of the hands that put a nation on wheels. His passion for machinery became an idea, and the power of that idea has rolled on through the years.

He learned how to run and fix and make every kind of machine there was. Then he began on the machine that wasn't—a horseless carriage.

In 1896, seven years before the founding of the Ford Motor Company, he trundled his first little two-passenger machine out into the alley back of Bagley Avenue in Detroit, and ran it around the block. It had two cylinders, four bicycle wheels and he steered it with a tiller, like a boat. He called it a "motor-wagon." Long since it has become a museum-piece, but it still runs—and it has had 36,000,000 descendants on the highways of the world.

His idea was to make a useful thing—as useful as possible, as low-priced as possible—a car for everyone. The Ford Motor Company was founded, on June 16,1903, in the hope the world was ready for the idea.

This year is the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Ford Motor Company, To us this anniversary has one meaning above all others—it means that this is still the kind of world in which a farm boy's useful idea can gradually bring about a better way of life for millions of people.

Henry Ford brought only his idea, his car and his bare hands to the company fifty years ago. Then the pavements ended just outside the cities, in dust tracks. Now the American Road means far more than a vast network of highways. It is a symbol of a never-ending search for progress, peace and plenty for all mankind.

The Ford Motor Coinpr.ny, in celebrating its 50th Anniversary, is dedicated to one simple pr ,f.' f, m; the best along that road is yet to be.

Ford Motor Company

Fifty Yean Forward on The American Road FORD . LINCOLN . »ffi|c iRY CARS . FORD TRUC^ AND TRACTORS

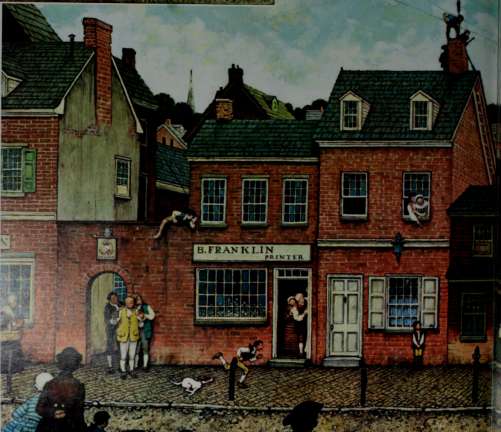

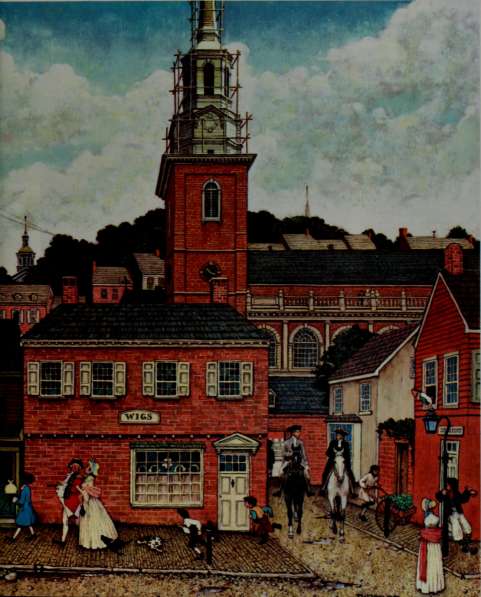

THE AMERICAN ROAD —XVI

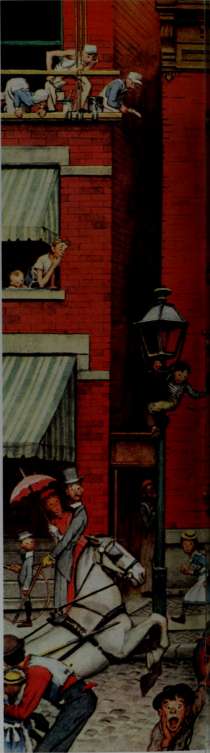

The street was never the same again

When the noise came, your Aunt Ella was always out back somewhere— and you were the one they screamed at every time to go find Aunt Ella. She wanted to see it with her own eyes.

So did you. The noise itself was strange and new and exciting—the little explosions pop-pop-popping regularly, the whining grind and the sudden clanks.

And then around the corner Henry Ford drove into your life, sweeping majestically by in the "contraption." There was no real name for it —Henry Ford himself called it a motor-wagon.

This was a fine high moment. Evenr1:hing froze in the glorious instant of surprise and shock. Then the horses skittered, the dogs began to yipe, and you and your friends chased madly along the street, shrieking the latest slang: "Get a horse!"

Then the motor-wagon chugged out of sight. The carpenter picked up his hammer again, the horses settled back in the shafts, and life went on.

In the chuckling crowd that drifted off, shaking heads and gossiping, there were very few who realized that they had seen something important. No one knew that the street would never be the same again—that American life itself was being changed. And certainly no one dreamed that this one little tvpe of motor-wagon alone would have more than 36.000.000 descendants.

No one but Henry Ford—and he was a hard-selling salesman simply because he was a man with a dream. He dreamed of transportation for the masses—a light, strong car made swiftly in such great quantities that everyone could own one.

He plugged away at the dream for seven years—and then on June 16, 1903, he organized the present Ford Motor Company.

That date is one of the prime milestones of the American Road, the way of life that has made this nation great. The American Road stands for the 3,322.000 miles of highways that network the nation today to serve the automobile, but it also stands for something far greater—the supreme essentiality of the automobile to modern bving.

The automobile began as simply a way for people to move about more swiftly and more comfortably. But now the auto has come to mean more-it is the base of our national mobility, the mobiUty that serves us in peacetime and defends us in wartime.

As .\mericans we break new ground every day and so we will forever. Always we hold before us the belief that the best is yet to be. And to that stubborn and realistic dream of life the Ford Motor Company dedicates itself in this year of its Fiftieth Anniversary.

Fifix YearB

Fontard

on The

Ammrieam

Ford Motor Company

FORD . uycoi^y • mercury cars

FORD TRUCKS AAV TRACTORS

What You See is What They Saw

Rockwell Admired These Masters of the Qolden Age*

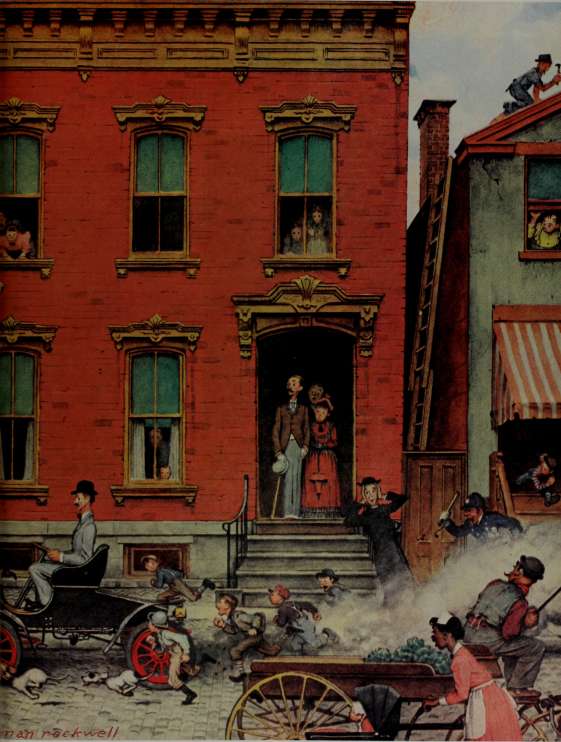

Illustrators there are who paint blurred, abstract visions to go with stories or advertising commissions they've been assigned, hoping thereby to be true to the cause of art and free from the confines of the story or the dictates of the art director. The picture in itself may be beautiful, may be art, may please the commissioner for these very reasons.

Rockwell's illustrations became art because the quality and scope of his paintings transcend the limits of illustration without violating the traditions and techniques of illustrative art. The emotional reach and grasp are broader in some of his more famous covers and illustrations than in the work of any other illustrator in history.

The style, the simplicity, the exaggeration of character are essen-

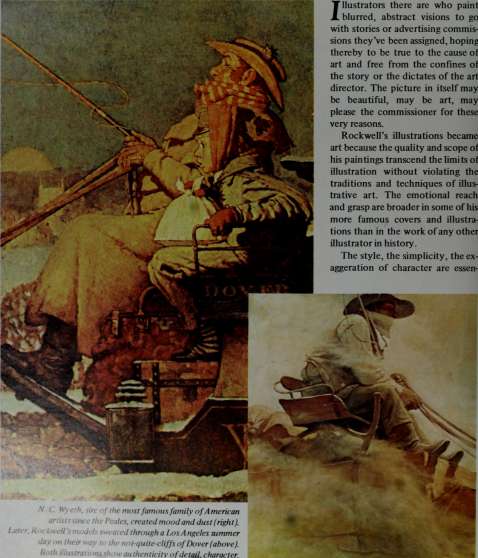

M C. Wyeth, sire nf the most famous family of A merican

artists since the Peales, created mood and dust (right).

Later, Rockwell's models sweated through a Los A ngeles summer

day on their way to the not-quite-cliffs of Dover (above).

Both illustrations show authenticity of detail, character.

For John Held, Jr., fashion was everything (right), flesh and

bones, nothing. The slicked-back hair of the men, the knobby

knees of the flappers beat a jazz tattoo that echoed

through the already noisy 1920's. Rockwell's real couple

(below) supply a variation on the theme that appealed to

broadway musicians Rogers, Hart, and Gershwin, as well as

artists and writers, Peter Amo, Anita Loos, Scott Fitzgerald

Z/ 4mr

tially nineteenth century, though Rockwell owes a great deal to the cartoon-type covers of early magazines—the Post, Life (when it was a humor magazine), and Judge. They were, in effect, visual one-liners. On the other hand, Rockwell's schooling was based on accuracy of figure and costume, telling gesture, the great tradition of Edward Austin Abbey, Howard Pyle, Frederic Remington, and Winslow Homer. Details were painted with painstaking authenticity. Models stood for hours with excruciating facial expressions. Studios were built to create mood and atmosphere. Hulks of ships, cottage window sills, medieval chambers were reconstructed with scholarly verisimilitude.

The so-called Golden Age of Illustration nurtured Rockwell. Once asked whether he'd rather

21

have a Rembrandt piiinting or a Howard Pyle. he chose the ilkistra-tor. He admired Pyle's authenticity, his ability to capture mood and mystery, his perfect bahince of in-telHgence and emotion.

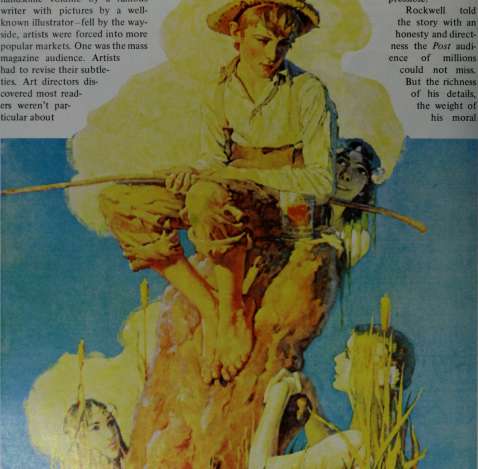

When the illustrated classic-a handsome volume by a famous writer with pictures by a well-known illustrator-fell by the wayside, artists were forced into more popular markets. One was the mass magazine audience. Artists had to revise their subtleties. Art directors discovered most readers weren't particular about

authentic detail; they wanted entertainment with a burlesque impact. "Illustrators," Rockwell remembered a friend

iiTS

saying, "were getting to be businessmen with a knack for drawing." Rockwell was caught up in this new wave of popular art, but his training, both as a draftsman and as an interpreter of humanity, was irrepressible.

Rockwell told the story with an honesty and directness the Post audience of millions could not miss. But the richness of his details, the weight of his moral

.ai L.

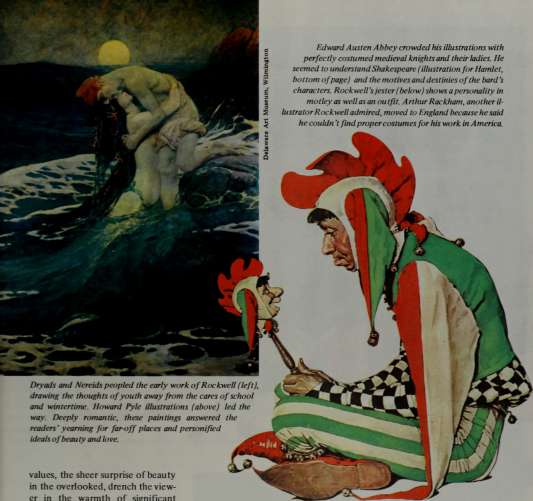

Edward Austen Abbey crowded his illustrations with perfectly costumed medieval knights and their ladies. He seemed to understand Shakespeare (illustration for Hamlet, bottom of page) and the motives and destinies of the bard's characters. Rockwell's jester (below) shows a personality in motley as well as an outfit. Arthur Rackham, another illustrator Rockwell admired, moved to England because he said he couldn 't find proper costumes for his work in America.

Dryads and Nereids peopled the early work of Rockwell (left), drawing the thoughts of youth away from the cares of school and wintertime. Howard Pyle illustrations (above) led the way. Deeply romantic, these paintings answered the readers' yearning for far-off places and personified ideals of beau ty and love.

values, the sheer surprise of beauty in the overiooked, drench the viewer in the warmth of significant human emotions.

"Part of the reason I went into illustration was that it was a profession with a great tradition, a profession I could be proud of. I guess my temperament and abilities were the other part."

Many fine artists have worked in tandem with themselves as illustrators. Remington, Glackens, Sloane, Hopper, Grant Wood, Andrew Wyeth all did pictures for the Post. In Europe, Goya, Daumier, and Toulouse-Lautrec worked for periodicals and did posters for special events. Often, illustrations must be abstract in concept, as

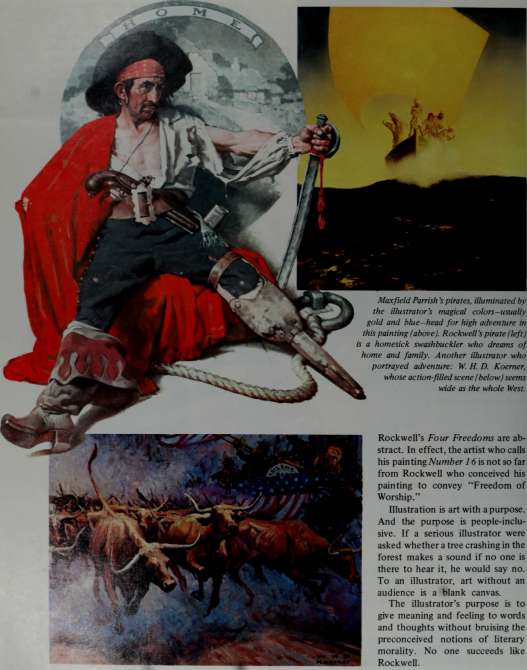

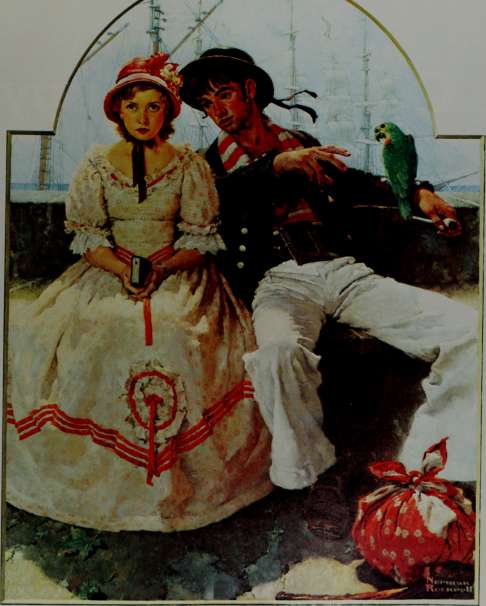

Maxfield Parrish 's pirates, illuminated by

the illustrator's magical colors-usually

gold and blue-head for high adventure in

this painting (above). Rockwell i pirate (left)

is a homesick swashbuckler who dreams of

home and family. Another illustrator who

portrayed adventure: W. H. D. Koemer,

whose action-filled scene (below) seems

wide as the whole West.

Rockwell's Four Freedoms are abstract. In effect, the artist who calls his ^2^r\Xmg Number 16 is not so far from Rockwell who conceived his painting to convey "Freedom of Worship."

Illustration is art with a purpose. And the purpose is people-inclusive. If a serious illustrator were asked whether a tree crashing in the forest makes a sound if no one is there to hear it, he would say no. To an illustrator, art without an audience is a blank canvas.

The illustrator's purpose is to give meaning and feeling to words and thoughts without bruising the preconceived notions of literary morality. No one succeeds like Rockwell.

This bell, featuring Mr. Roclovells famous "Triple Self-Portrait." has been authorized by the Saturday Evening Post for issuance exclusiv'ely through the Danbury Mint.

Advance reservations are being accepted now. The bell will be available for shipment in early Spring. Please use the attached reservation form or send reservation to: The Danbury Mint, 47 Richards Avenue, Non\^alk. Conn. 06856

©1979CPC

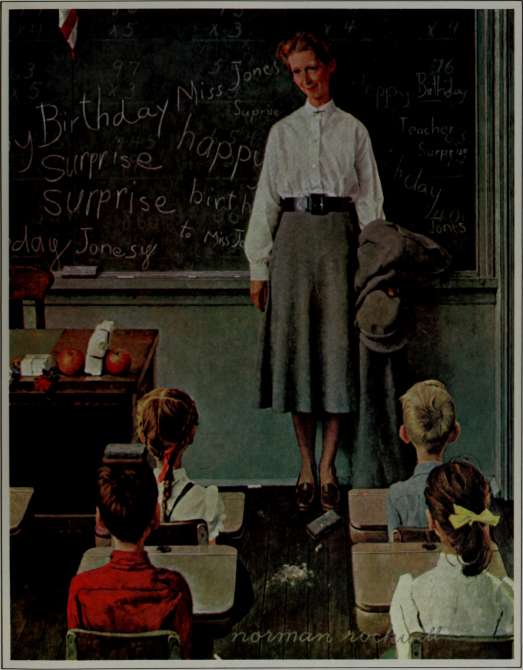

A Country School

The "open wide"for the visiting nurse.

Meeting the school board. Now it's the teacher's turn to recite.

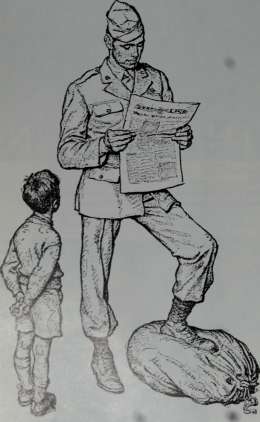

The children in these sketches are students at Oak Mountain School, which sits atop a tall clay hill in Carroll County, Georgia. Rockwell visited it in a "small year" when there were only 40 pupils; some years there are 75. The school was commended to the artist by leading educators who think the teacher, Mrs. Effie McGuire, does an exceedingly good job. Mrs. McGuire loves her work, and it is a good thing she does, for this weather-beaten clapboard schoolhouse has all the shortcomings of its kind. The plumbing is outdoors, the washbowl is on the porch, and someone has to tote coal for Big Joe, the stove. The pay is thin soup; it has been as low as $420 a year, and even now is only $878. (1946)

It's his own, his native soil, but the rule is firm: Geography is to be studied, not to be worn.

Spelldown. Just remember, it's \ before e, except after c—except for the excep tions.

Day to shine: mothers present

A prize chore.

They'll hear that

bell today.

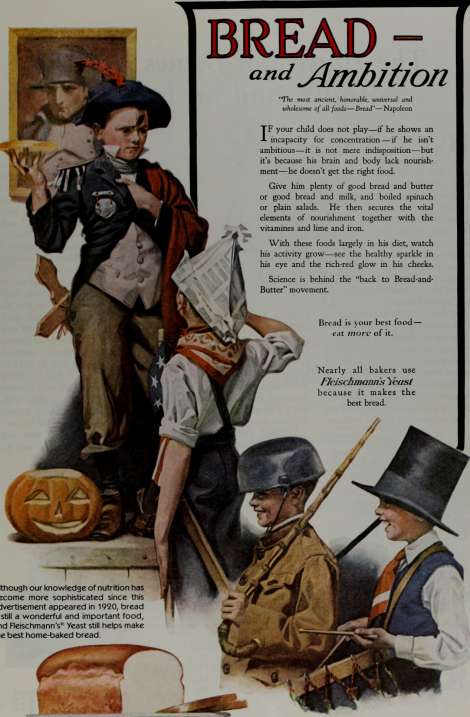

Although our knowledge of nutrition has become more sophisticated since this advertisement appeared in 1920, bread is still a wonderful and important food, and Reischmann's" Yeast still helps make the best home-baked bread.

ftifHtdfoT TV Fttiuhmnn Co. h Norauo /.'j. *»<■«

The Illustrator Draws Breath, Straws, and an Income

He was born in New York City, the grandson of a professional artist, the son of an amateur artist. Rockwell was trained and disciplined in a trade. His education sin-gle-mindedly bore down on the talents he was born with and had already started to develop as a child. He entered the Chase Academy, and later the precision of his draftsmanship gained him a scholarship at the Art Students League.

At these schools, Rockwell took courses in illustration. He intended to become an illustrator. Illustration was a means of making a living and, of equal importance, a means of expressing emotion.

His linkup with the Post was significant. Many magazines were exploring photography and abstract ideas as cover art. But the Post nur-

tured a kind of sincerity in its contributors and readers that only representational art could make concrete. Serious entertainment, i.e., humor, was the business of the magazine, and Rockwell, hardened by city Hfe and freshened by visits to the country, was a young man of perfect paradox, anecdotal, moral.

Rockwell embraced the magazine and all its philosophy. George Horace Lorimer, the Posfs famous editor, believed great literature ought to be wholly digestible. He was prepared to batter-dip his literary morsel in amusing and bright covers. He didn't care for names as long as the writers gave him a good story. And if authors had great names and turned in trash, back it went. He bragged that other magazines made up their copies from his rejections. "Mr. George Horace Lorimer," wrote Rockwell (who never mentioned Lorimer without the "Mr."), "had built the Post from a two-bit family journal with a circulation in the hundreds to an influential mass magazine with a circulation in the millions. He was The Great Mr. George Horace Lorimer, UIb baron of publishing. What

if he didn't Uke my work?" He did.

And the rest is amusing history.

But Rockwell did his best work for editor Ben Hibbs, "the archetype of the easygoing, good-natured Midwesterner," according to Rockwell, but with "iron in his soul" and, something rarer, "integrity, absolute integrity," as editors who worked with him said.

Hibbs' method was to give Rockwell the freedom to choose his own topics and work them up within the new cover format. (The famous Guernsey Moore hand-lettered logo gave way in 1943 to the block-lettered POST.) Hibbs praised Rockwell, whereas Lorimer kept the artist on a tight lead, changing designs, making suggestions that often amounted to commands. Still, the two men had (Continued to page 30)

The good life, 1979 style. That's Cadillac.

Lively. Responsive. Beautifully agile.The new DeVilles and Fleetwood

Brougham are designed for the way you live today. Yet, cars of classic elegance-

with all the luxury, comfort and convenience that have long made Cadillac America's

favorite luxury car. See the luxury leaders at your Cadillac dealer now.

I

enormous respect for each other. And Lorimer's discipline helped create Rockwell's climate of work, his devotion to duty and deadline. Hibbs considered Rockwell the real victorious general of World War II. He felt The Four Freedoms, especially "Freedom of Worship" and "Freedom of Speech," which hung in his Philadelphia office, were great art. "They are a daily source of inspiration to me," he said, "in the same way that the

clock tower of old Independence Hall, which I can see from my office window, inspires me. If this is Fourth of July talk, so be it. ... I regard [the pictures] as great art. Norman himself probably would disagree. He has always modestly labeled himself an 'illustrator'with no pretensions to fine art. I suspect art critics would say that those two pictures are excellent examples of an illustrator's work at its best, but not great art. I am no art critic, but I still disagree. To me they are great human documents in the form of paint and canvas. A great picture, 1 think, is one which moves and inspires millions of people. The Four Freedoms did-and do."

Rockwell's life was not always the happy iifeheoainted.

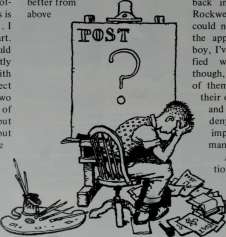

He suffered through a divorce, a tragically ill wife, bouts when he felt he could not paint or that his work was no good. His solution to every difficulty was to go to his easel at eight every morning. He wrote several years ago, "I've got pains in my knees and my hair is almost white. I've developed a fondness for afternoon naps. I go to bed early almost every night. 5w/^, I get up early every morning. I'm at work by eight. I still play a fair game of badminton. I no longer believe that I'll bring back the golden age of illustration. I realized a long time ago that I'll never be as good as Rembrandt. But, I think my work is improving. I start each picture with high hopes, and if I never seem able to fulfill them, I still try my darndest. . . . The daisies do still look better from above

than from below. Somebody once asked Picasso, 'Of all the pictures you've done, which is your favorite?' 'The next one,' he replied."

Rockwell painted thousands of pictures. Museums and critics say Rockwell does not figure in the development of the history of art. The Rockwell in the Metropolitan's collection is lent out to decorate the office wall of a Borough president. Many collections do not even have a Rockwell. When the Met ask-

ed Rockwell for the painting in its collection 20 or so years ago, the then-director said it would be nice centuries from now for art critics "to see what people looked like" back in the twentieth century. Rockwell himself admitted "I could never be satisfied with just the approval of the critics, and, boy, I've certainly had to be satisfied without it." His works, though, stand as a sort of criticism of themselves. They exist within their own standard of excellence and popularity. No one can deny their importance or the importance of the witty, kind man who created them.

An early Rockwell illustration for a Post cover was sold in December 1978 for 543,000, and business magazines were pointing out at the time of the artist's death that his (Continued on page 32)

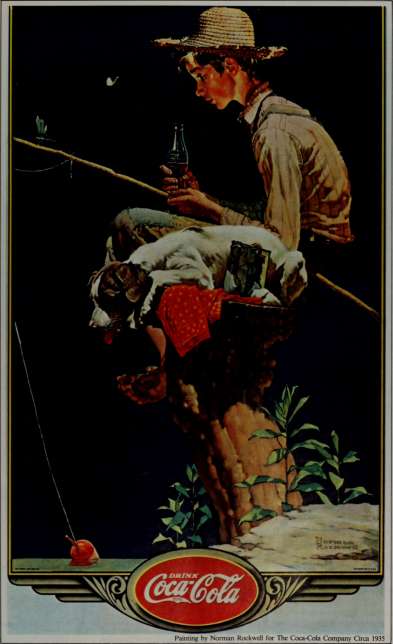

Cop>Tighi ? 1979. The Coca-Cola Company. "Coca-Cola" and "Coke" are registered trade-marks which identify the same pfx)diict of The Coca-Cola Company.

THE COCA-COLA COMPANY AND ITS BOTTLERS AROUND THE WORLD ARE PROUD TO JOIN IN THIS TRIBUTE TO NORMAN ROCKWELL, AN AMERICAN INSTITUTION AND AN OLD FRIEND.

works were a good investment. Rockwell was paid $75 for that cover. But, as he himself said, two million people looked at a Post cover, probably more. "Two million subscribers, and then their wives, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles, friends."

"When I had added the Post cover to my portfolio the art directors of the other magazines began to give me assignments." His covers brought him five and six thousand dollars in the '40's and '50's, but more than that, they brought him the fame and freedom to dare a vision at which most illustrators would've quaked as one being pretentious and beyond the scope of illustrative art. Success, as they say, breeds success, and Rockwell's name and face were well known enough to cause readers to demand more than the merely good. Rockwell did not cringe at the challenge.

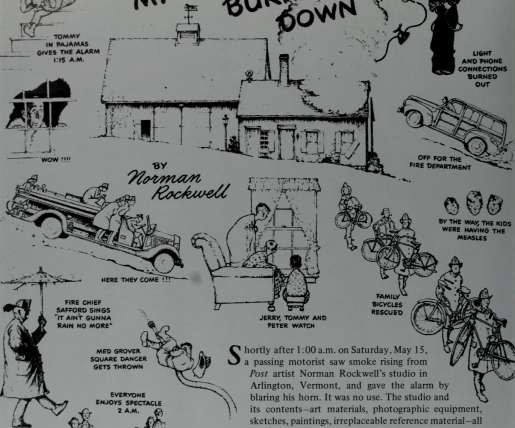

He worked like a horse. The assistants and models and photographers and art editors who worked with him recall his getting to the studio before 8:00 a.m., his waking people up in the middle of the night to have a stage built or a picture taken so he could start work early the next day. And he traveled and studied, both in the U.S. and in France, so that new ideas were constantly flowing through his old experiences. When his studio burned in 1943 he said he was glad in a way because "you get too tied to old pattern books, bits and pieces of costume." Few artists could've stood the calamity, but Rockwell went on to paint his greatest covers, laughing at an artist friend who'd said, "If the average person liked a painting of mine, I'd destroy it," and another who explained, "I think I'll take up fine arts. Commercial art is too difficult."

Small and subtle differences between the charcoal sketch for a Post cover (above) and the finished painting (below) show Rockwell's painstaking attention to details that deepen and enrich characterization. Note woman's hands, hair.

ITS SO SIMPLE

cJ ELL'O

BRAND

G E L A.T I 3Sr

Americas most famous dessert

THE great merit of Jell-O Brand Gelatin is that it is always ready. It is made as easily as a cup of tea is brewed. Write for a free booklet describing a w^ide variety of uses.

Ihe Genesee Pure Rx)d Company. Le Roy. New York

Canadian Factory at Bridgeburg, Ontario

©192 2 BY THE. CeNESEE PURE FOOD COMPANY

©General JELL-O

Foods Corporation 1979.

is a registered trademark of General Foods Corporation, White Plains. N.Y.

Elements of this advertisement first appeared in the December 1, 1923, Post.

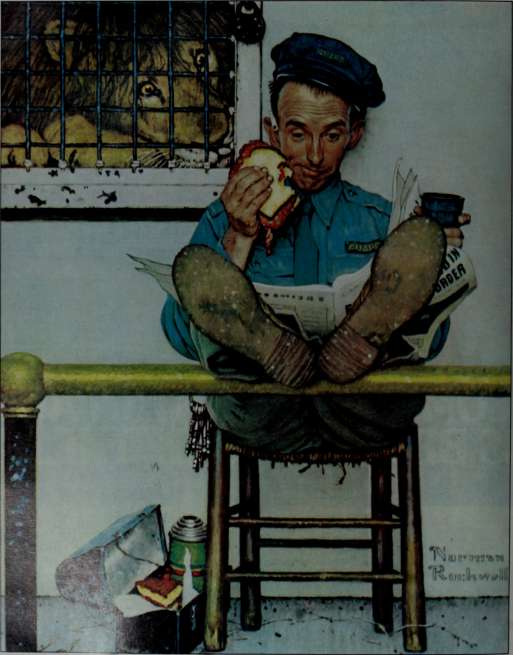

Rockwell Loved A Loser

By John Alexander

W''hen everything has been said—what a great draftsman Rockwell was, what an eye for detail he had, wasn't he the droll one, and my! couldn't he see clear through the foibles and pomposities of mankind?—perhaps in the end why America took him to its heart was his pure humanity.

When one adds up all his works, it is the span of emotions Rockwell could orchestrate like a symphony conductor which is so impressive. When he tuned in on themes like The Four Freedoms he could strike chords in the human heart like a Beethoven or a Brahms. His old duffers, his feisty old ladies, the Romeo-and-Juliet quality of his young lovers are a virtuoso performance in the interpretation of the human condition.

But what a heart that little artist had in his small

frame! Frail as he was in stature, he had a godlike view of what life could do to its losers, and he tried his level best through his art to even things up for them, if only in imagination.

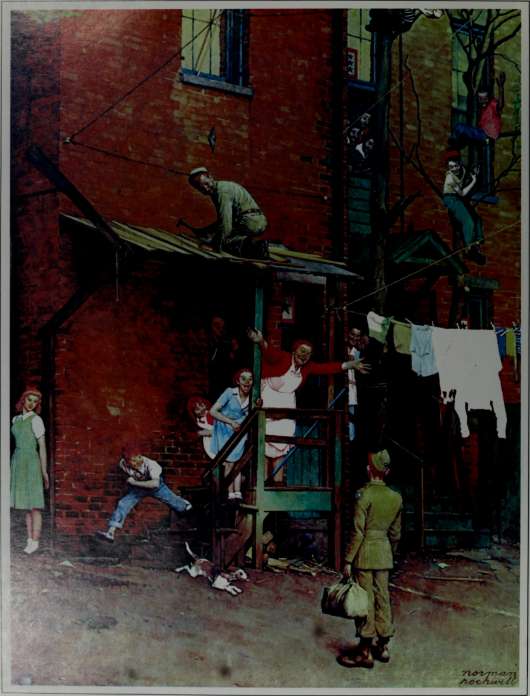

Try, if you dare, to eavesdrop on the moment captured here, the Rockwell painting of a man being welcomed by his dog, and not be moved by it. Mark well the battered valise, the bumbershoot, the shapeless hat, the homemade haircut, and the country bumpkin clothes of the man just returned from the Grand Hotel in the big city. Here is mute evidence of the half-hidden smiles of derision, stifled laughter, and possibly even the jeers he had to endure for the sake of whatever took him to where he didn't belong. Norman Rockwell makes him well again, heals all those scars of the spirit, with just one lick by the

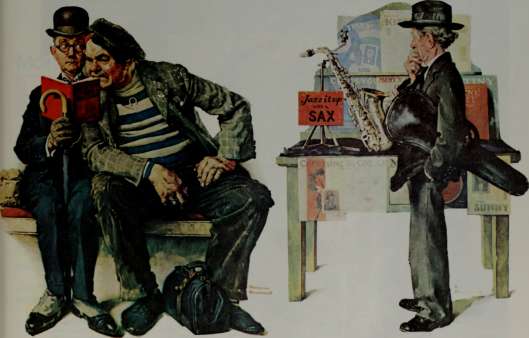

Three variations on the "little guy" theme. These Post covers appeared in 1924 (opposite), 1927 (above), and 1929 (right).

Favorite model James K. Van Brunt posed as the classical musician pondering a new musical phenomenon jazz.

rough tongue of dog, welcoming him home.

It happens time after time with Rockwell. Sometimes the happy ending can never be, only a poignancy so touching the beholder would like to jump in there and help—as when the little old violinist reads his sad fate in the wail of the newfangled saxophone.

Occasionally, the loser smashes through to his great beyond, to the joy of all concerned. Note the bruiser taking over from the gentle scholar on the park bench. This time it is matter over mind. Somehow we rejoice that the proper roles are reversed.

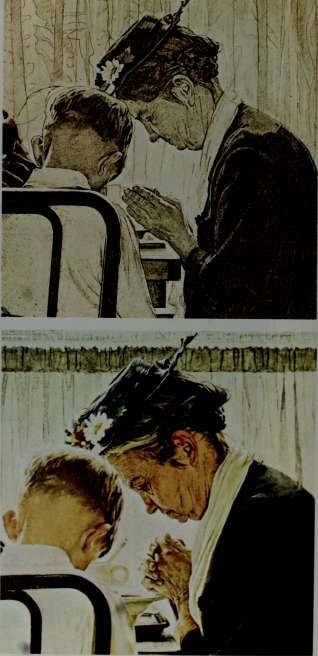

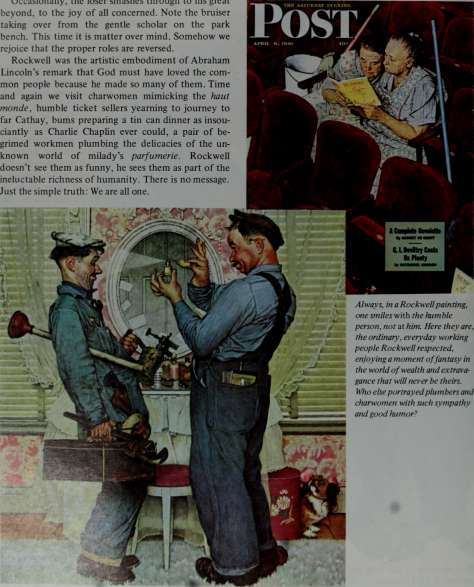

Rockwell was the artistic embodiment of Abraham Lincoln's remark that God must have loved the common people because he made so many of them. Time and again we visit charwomen mimicking the haut monde, humble ticket sellers yearning to journey to far Cathay, bums preparing a tin can dinner as insou-ciantly as Charlie Chaplin ever could, a pair of begrimed workmen plumbing the delicacies of the unknown world of milady's parfumerie. Rockwell doesn't see them as funny, he sees them as part of the ineluctable richness of humanity. There is no message. Just the simple truth: We are all one.

Always, in a Rockwell painting, one smiles with the humble person, not at him. Here they are, the ordinary, everyday working people Rockwell respected, enjoying a moment of fantasy in the world of wealth and extravagance that will never be theirs. Who else portrayed plumbers and charwomen with such sympathy and good humor?

FREE...this handy, walnut-finished BOOK RACK

when you preview the revolutionary ^^

BritdinkQ 3 "--"^ ^ ™^

How to get this MAGNIFICENT BOOKCASE-

a ^59'" valiie-FREEwith Britannica 3.

Get your FREE book rack just for previewing Britannica 3. Then, if you decide to acquire The New Britannica 3, you'll also receive this magnificent pecan-finished bookcase— a $59.50 value—absolutely FREE!

For over two hundred years.. the old idea of the encyclopaedia remained the same. But now, to meet the demands of our changing world with its vast amounts of information... now, there is Britannica 3. This is a completely re-designed encyclopaedia. It is written in clear, readable language ... the language of today... so that even the most complex subjects become much easier for your children to understand.

What makes Britannica 3 unique?

New Britannica 3 is more than an encyclopaedia. It's a revolutionary Home Learning Center... America's only encyclopaedia arranged into three distinct parts.

1. The 1()-Volume Ready Reference lets you get at tacts, quickly and easily. Ideal for homework.

2. 19 Volumes of Knowledge in Depth for readers who want to explore entire fields of learning.

3. The One-Volume Outline of Knowledge —your guide to the entire encyclopaedia

.. permits you to plan your own course of study on any subject under the sun.

Britannica 3 covers more subjects more completely. It is more responsive to the current needs of your family. And when you judge by its 43 million words, you'll agree that Britannica 3 delivers more value per dollar than any other accepted

Get this handsome walnut-finished book rack free— perfect for keeping your favorite books handy—when you preview The New Britannica 3.

reference work. So if you want more up-to-date facts about more subjects than you'll find in any other single source, you want The New Britannica 3?

Preview Britannica 3 FREE

New Britannica 3 is like no other encyclopaedia you have ever seen. Indeed, it's the first new idea in encyclopaedias in 200 years. That's why we've created a special full-color Preview Booklet which pictures and describes this achievement in detail. This Preview is yours free... no obligation... so please send for it today.

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.—also publishers of Great Books of the Westem World.

140-D

// card has been

removed, write to

Encyclopaedia Britannica,

Dept. 120-K. 425 N. MichiBan

Ave., Chicago, Illinois 60611

Mail card above for your FREE PREVIEW and BOOK RACK

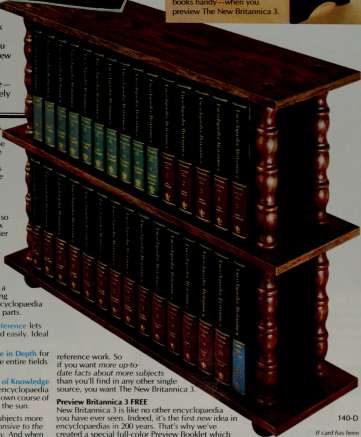

Symphony conductor Arturo Toscanini (right) symbolized the pleasures of serious music to generations that would have included both man and boy in Rockwell's 1947 painting The Piano Tuner ^a6ove/ A neighbor, George Zimmer, posed under the supervision of a real piano tuner recruited from Bennington.

The Pleasures of Music by Aaron Copland

W^ musicians don't ask for much. All wc want is to have one investigator tell us why this younji fellow seated in row A is firmly held by the musical sounds he hears, while his [?ir|friend gets little or nothing out of them, or

vice versa. Think how many millions of useless practice hours might have been saved if some alert professor of genetics had developed a test for musical sensibility. . . .

If misic has impact for the mere listener, it follows that it will have

much greater impact for those who sing it or play it themselves with some degree of proficiency. Any educated person in Elizabethan times was expected to be able to read musical notation and take his or her part in a madrigal sing. Pas-

i*<\ \

OFCOURSEIOUIN A RABBIT.

WHArrooL

WOUUOWN ACOPY?

'Based on 1977 leSf. ©««>lksw»gc»i of America, iik:.

The Volks-

wa g e n

Rabbit is

the most

copied car in America.

So many cars look like Rabbits, you can hardly count them. But you can sure tell tt^ey aren't Rabbits if you know what to look for. Look for front-_- wheel drive. Very "" few cars have it. vMiich is too bad. Because front-wheel drive will help you up, around and through hills, turns, curves and nasty weather.

Look for fuel injection. Which is mighty hard to find, except for the Rabbit. You will not find fuel injection on any Toyota. Or Renault. Or Honda. Or Mazda. Or Subaru. Or any Ford or Chevrolet or Plymouth or Dodge or Buick in Rabbit's class. So there. Look for performance. For

capacity. For handling. Vfery few cars in Rabbifs class combine the ability to carry as much and accelerate in the 8.3 seconds it takes the Rabbit to go from 0 to 50 m.p.h.

Even General Motors named Rabbit the best of five economy cars tested. And one of them was their own.*

So ifs up to you.

You can drive the original or you can end up in one of a million copies.

But you can't say we didn't warn you.

WLKSIMAGEN IT

I I ^

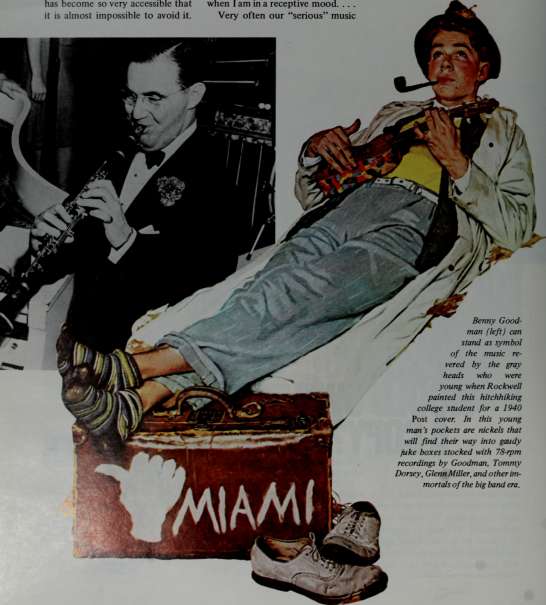

sive listeners, numbered in the millions, are a comparatively recent innovation. Even in my own youth, loving music meant that you either made it yourself or were forced out of the house to go hear it where it was being made, at considerable cost and some inconvenience. Nowadays all that has changed. Music has become so very accessible that it is almost impossible to avoid it.

Perhaps you don't mind cashing a check at the local bank to the strains of a Brahms symphony, but I do. Actually, I think I spend as much time avoiding great works as others spend in seeking them out. The reason is simple: Meaningful music demands one's undivided attention, and I can give it that only when I am in a receptive mood. . . . Very often our "serious" music

is serious, sometimes deadly serious, but it can also be witty, humorous, sarcastic, sardonic, grotesque, and a great many other things besides. It is, indeed, the emotional range covered which makes it serious and, in part, influences our judgment as to its artistic stature.

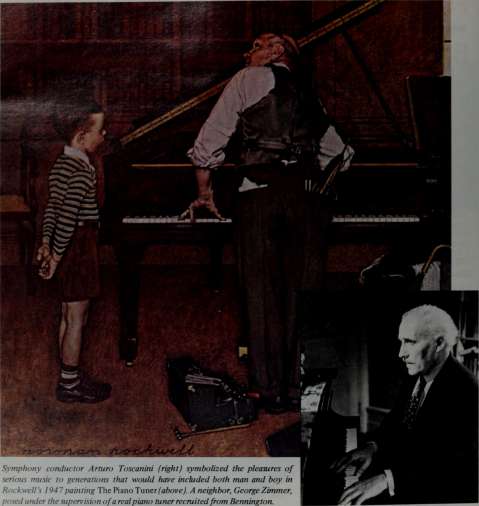

Benny Goodman (left) can stand as symbol of the music revered by the gray heads who were young when Rockwell painted this hitchhiking college student for a 1940 Post cover In this young man's pockets are nickels that will find their way into gaudy juke boxes stocked with 78-rpm recordings by Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, and other immortals of the big band era.

Instant movie star.

We all tend to get a bit self-conscious when we get before a camera—especially a movie camera.

Yet, if the truth be told, we all secretly itch to see ourselves on the silver screen.

Maybe it's the effect of Hollywood, or maybe it': just human nature, but there it is. ^t^ We wonder tj^ what we'd look like.

Take movies of any group of people, and show them the movies, and every one of them will look at himself, or herself, first.

"Oh, Hook awful!"

"Gee, is that really me?"

"Suzy looks terrific, but hair's a mess (Translation: "Even with messy hair, look twice as good as Suzy.")

It's curious. ^^

You r

never get anyone saying, "I really look great." That would be immodest.

However, one thing becomes immediately apparent. Everyone else looks pretty much like you expected.

Because, unlike photographs, movies don't catch you in that 1/100 of a second when you bUnked, or had an unfortunate expression on your face.

The movie camera gives you the opportunity to see yourself as others see you.

■PWarod" and Polavison*" ® PDIaroNjCorp 1978 S»nulated picture

Polavision is Polaroid's name for instant movies.

They're actually easier to take than conventional photographs.

The film develops in the player automatically.

You just pop the Polavision cassette into the player, and you're ready to watch.

The first time you

view the film after

you shoot it, it

takes 90 seconds

to develop.

Every time after that, it takes only 8 seconds to come to life.

Over and over again, if you like. There's no screen to put up and take down. No projector to thread and rewind.

It's so easy, your preschooler can do it. When the film is over, the cassette pops up like a shce of

toast, and the player turns itself off automatically.

You don't even need to store the player It's compact, and well designed, so you can leave it sitting out, plugged in, if you like.

So your kids can look at your movies (or their movies—it's that simple) whenever the mood strikes them.

And because it's not a big production to watch Polavision, you can see what your acting talent is like.

So don't be surprised^ if, after shooting a couple of movies, you stop thinking of yourself as a director.

And hand the camera to someone else, and start thinking of yourself as a star

Polavision from Polaroid

Everyone is aware that so-called serious music has made great strides in general public acceptance in recent years, but the term itself still connotes something forbidding and hermetic to the mass audience. They attribute to the professional musician a kind of initiation into secrets that are forever hidden from the outsider. . . . But, in all honesty, we musicians know that in the main we listen basically as others do, because music hits us with an immediacy that we recognize in the reactions of the most simple-minded of music listeners. . . .

No discussion of musical pleasures can be concluded without mentioning that rituaUstic word "jazz." But, someone is sure to ask,

is jazz music serious? I'm afraid it is too late to bother with the question, since jazz, serious or not, is very much here, and it obviously provides pleasure. The confusion comes, I beUeve, from attempting to make the jazz idiom cover broader expressive areas than naturally belong to it. Jazz does not do what serious music does either in its range of emotional expression or in its depth of feeling or in its universality of language—though it does have universality of appeal, which is not the same thing. On the other hand, jazz does do what serious music cannot do—namely, suggest a colloquialism of musical speech that is indigenously delightful, a kind of here-and-now feeling,

less enduring 'than classical music, perhaps, but with an immediacy and vibrancy that audiences throughout the world find exhilarating.

Personally, I like my jazz free and untrammeled, as far removed from the regular commercial product as possible. Fortunately, the more progressive jazz men seem to be less and less restrained by the conventionaUties of their idiom, so little restrained that they appear in fact to be headed our way. By that I mean that harmonic and structural freedoms of recent serious music have had so considerable an influence on the younger jazz composers that it becomes increasingly difficult to keep the categories of jazz and nonjazz clearly divided. Anew kind of cross-fertilization of our two worlds is developing that promises an unusual synthesis for the future.

Thus, the varieties of musical pleasure that await the attentive listener are broadly inclusive. The art of music, without specific subject matter and little specific meaning, is nonetheless a balm for the human spirit; not a refuge or escape from the realities of existence, but a haven wherein one makes contact with the essence of human experience. It is an inexhaustible font from which all of us can be replenished.

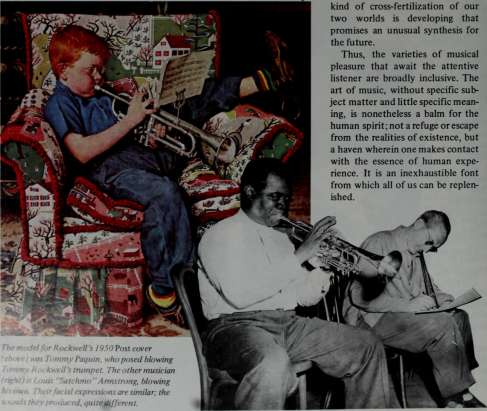

The model for Rockwell's 1950 Post caver fabovp) was Tommy Paquin, who posed blowing Tommy Rockwell's trumpet. The other musician (right)i<!Louis "Satchmo"Armstrong, blowing his own. Their facial expressions are similar; the sounds they produced, quite^ifferenl

On November 10,1956 this advertisement in the Saturday Evening Post

told the world about the confidence, professionalism and involvement of Pan Am

people. The standards haven't changed. Pan Am hasn't changed.

We fly the world the way the world wants to fly.

November 10, 1956'

.^

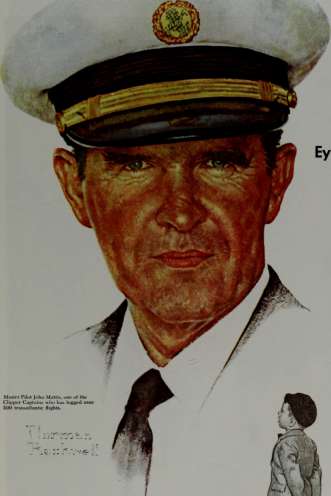

Master Piliil John Maltis, one o( the Cliliper Captains who liu!> lugged over 5UU traii^llantic flights.

'_g: ;:r.vv^j

Eyes that see

around the world

The look of experience is something all CHpper* pilots have.

It comes from watching the weather through all the Seven Skies over all the Seven Seas—year in and year out.

It's the look you want in your pilot when you fly overseas. And it's one great reason why more people choose Pan American when they fly overseas.

For on every Clipper flight deck there are as many as three qualified over-ocean pilots-trained to American standards; there are no standards more rigid or exacting in the world.

And beneath every Flying Clipper, all around the world, there extends the great supporting network of watchful experts—the vast ground forces of Pan American, 17,600 strong—maintenance men, weathermen, chefs and engineers.

In the skies, or on the ground in over 600 offices, these are the people who make jKissible the fastest, most frequent service from the U, S. to anywhere in 80 countries.

When you fly the Clippers, the finest of America flies with you.

P/m^MKRiGW

WORLD'S MOST EXPERIENCED AIRLINE

• Trsdc-Harlc. Itoz. U. S. Pal. OO.

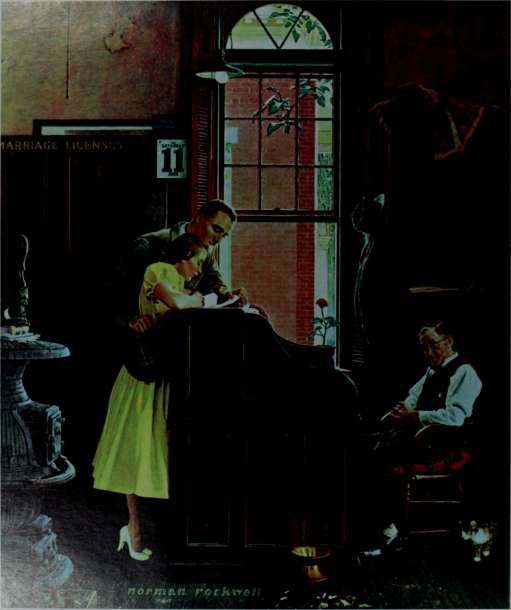

Love & M^arriage

They Qo Together, In the Axtisth W>rld

Norman Rockwell, a romanticist to the core, saw no harm whatsoever in portraying true love as one of this world's delights and marriage its inevitable finale. Thus, through some of his most charming paintings runs the theme of bittersweet young dreams and trials, with the happy ending just around the corner. Starchy Uttle misses and prickly tomboys inevitably

Omrfship, marriage, family life these are the realities that provide magazine artists with their most durable themes. Sometimes the treatment is frankly sentimental; sometimes it is tkimorous. Tlie Facts of Life (above) belongs to the latter classification. It is obviously too late to lecture the cat one of many cats that doze or frolic in Rockwell paintings.

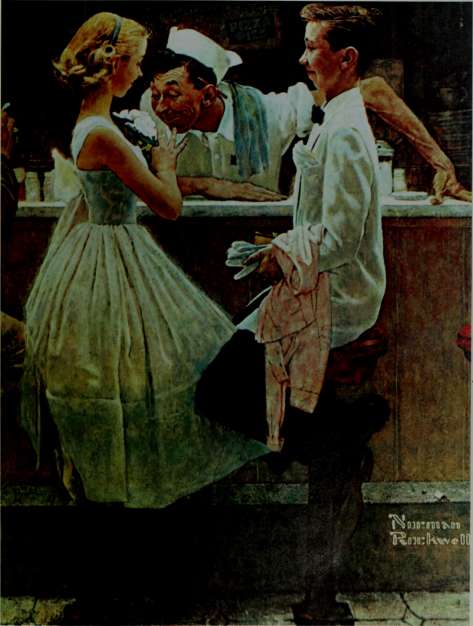

Rituals of courtship still existed in 1958. For flint: ordering flowers, arriving early enough to spend five minutes with her father in the living room, promising he 'd drive carefully and bring her home-after a stop at the soda fountain by midnight.

blossomed into shy young things demurely bussed under the mistletoe by gawky young giants, half boy, half man. Wedding bells chime softly offstage-see next week's cover for the bemusement and bliss of young married life. Was theie a harsher world b^ond? Of

course. Uncle Norman knew that well. The coil and clamor of reality would be upon them, all too roughly, all too soon. So, he just smiled with that gentle, faraway look in his eyes, and seemed to say: Let them be for now, let them be happy.

Sentimentality is most comfortable in costume, be it cloak and dagger, doublet and hose, or hoopskirt and bonnet. Romance lost (Mt to humor around 1940 when historical scenes like this one-a 1930 Post cover-fell out of favor.

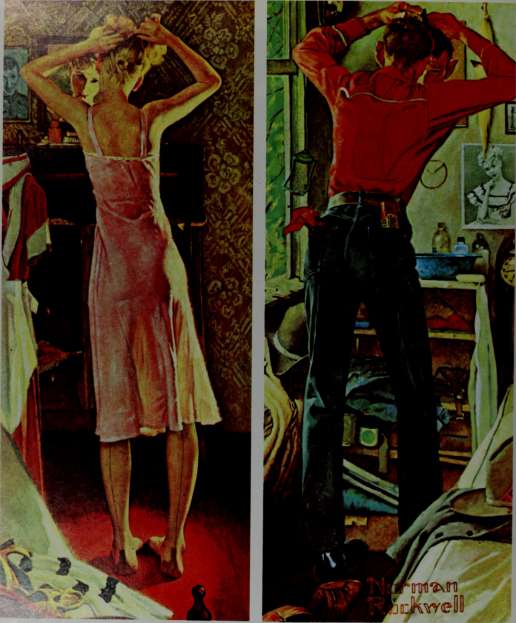

(Left) Styles change, but not attitudes. So might Priscilla have fussed with her hair when expecting John A Iden to call: so might the lovesick swains of Booth Tarkington 's novels have plastered down their cowlicks with brilliant ine.

The chance that Mrill never con\e again.

^uDscriDe now to tne c^aturaay i:;(^ning Post and get this historic issue FREE!

he editors of the Post left no stone unturned to make this issue one of the most memorable ever published. We built it around some of Rockwell's finest work and the memories of those who knew him best. But perhaps the high point is the glowing portfolio of The Four Freedoms, the paintings that inspired and electrified the world. We planned in advance to print these exquisite interpretations full-page on heavy stock, separately presented, so that you can frame them right out of the magazine pages. (We'll tell you how you can frame them when you receive your copy!) Also included are the moving descriptive texts originally written to accompany the paint-

ings, literary masterpieces by Booth Tarkington, Will Durant, Carlos Bulosan, and Stephen Vincent Benet.

Included among the many Rockwells is "When Your Doctor Treats Your Child," for which his wife Mary and two of their boys posed. This gentle classic was originally sponsored by the Upjohn Company and reappears in this issue as an Upjohn tribute to the master.

All in all, a publishing occasion. Free with new subscriptions. But a word of precaution: Order now, because this free keepsake is available only while our supply lasts.

THE SMTUHnaY EVBNMMLPOST

Poiindci

rMiklln

imL/nb.19

America's

Favorite

Artist

Rockwell's The Four Freedoms to Frame

I I

M.M

The

Valentine

by James

Jones

Alexander

Haig, Jr.

Exclusive

Interview

NORMAN ROCKW^ii

JL %.^^^ ^m^JL ^^ 1 Matting guide for stc

y^/ ^^m

r //f ^^/y//// r /,

sjtTvap/ir

9:1;

NORMAN ROCKWbLL

This guide (sent separately) will help to put any

print on your own wail or on someone else's. A

natural follow-through to this great offer!

stock 12 X 16 frame

Daniel Webster and the Ides of March

a story by StephenVincent Benet

They say that in the life of every great man there's one Httle thing he finds it hard to beat. It may be a bodily ailment or a man that stands in his way, a memory back in the past or an unfulfilled ambition. But whatever it is, it's the drop of sour in the cup.

Well, that happens to all of us, but it's harder on the great man. Particularly when it's a small and niggling thing. For, in some ways, it's easier to face a great sorrow than the thought of a pair of tight shoes, and kings and queens have walked the floor with the tooth-

ache when they didn't over problems of state.

All the same, you'd think that a man like Daniel Webster would be exempt from such infinnities. And so he was, for the most part. He had debts, but they never worried him; he had enemies, but he gave as good as he got and didn't let them bother his peace of mind. He could work the hind legs off most men, whether at law or farming, and still be fresh as a daisy in the evening, when the time came to get out the jug. He had every mortal honor a man could have, except for being Presi-

dent, and, at that, he was bigger than most Presidents, and knew it. But all the same, there was the sour in the cup for Daniel. For Daniel Webster had hay fever.

It sounds like a small and niggling thing, now, doesn't it? But if you've ever had it, you know what it's like. It's 20 little devils inside your nose, each one with a bucket of hot brimstone—not to speak of the ones that take care of your eyes and throat. No, nobody's died of it yet. You only wish you could. And there isn't a more ridiculous object in the world than a man that's suf-

fering from a bad case of hay fever.

Daniel had the regular kind, the kind that comes with the ragweed and ends with the first frost. Some years it would be better than others and some years it would be worse, but pretty near every year he'd wake up one morning at Marshfield and let out a sneeze you could hear as far as New Hampshire, and then he'd know he was in for it. Oh yes, he tried all the things. He tried bleeding and cooling draughts and ice on the back of his neck, and a bushel of doctor's remedies. But he found, after long experience, that cussing and the White Mountains did as much for it as anything, and sometimes even they didn't do much.

He was getting to be an old man at the time I'm telling you about, though you wouldn't have thought it of him. But Daniel Webster knew.

He could still wrestle his ram, Goliath the Second, his fly still dropped on the trout stream as light as a falling leaf, and the shotgun he called Wilmot Proviso carried straight and true to the mark. There was silver and gold still left in the voice that had replied to Hayne. And if he was sure of anything, he was sure that he could still tackle the job of being President, once he managed to get the chance. But, for all that, he was 67, and his great days lay in the past. He knew that when he looked around the halls of Congress and saw the new faces. For he knew, if anyone did, what senators and congressmen ought to look like—and these didn't look like senators or congressmen. They looked like pink-cheeked children, and more and more of them were from states that hadn't even been pupped when Daniel Webster first

took his seat in the Senate. It's a strange thing when that happens to a man and he knows his age.

All the same, he was Daniel Webster, and, old or young, he didn't intend to have such things bother him. But what did bother him was his hay fever, and it came back on him that summer something ferocious. He didn't usually start it before the first week in August. But this time it was only the last week in July when he woke up in the morning with his throat like the pit of a volcano. And he'd sneezed seven times in succession and blown a pane of glass out of the window before he could even begin to stop.

"Now all my Hfe I've been plagued and crossed by three things." said Daniel Webster. "Hay fever, John C. Calhoun, and Henry Clay. Well, Clay's not the man he (Continued to page 100)

»

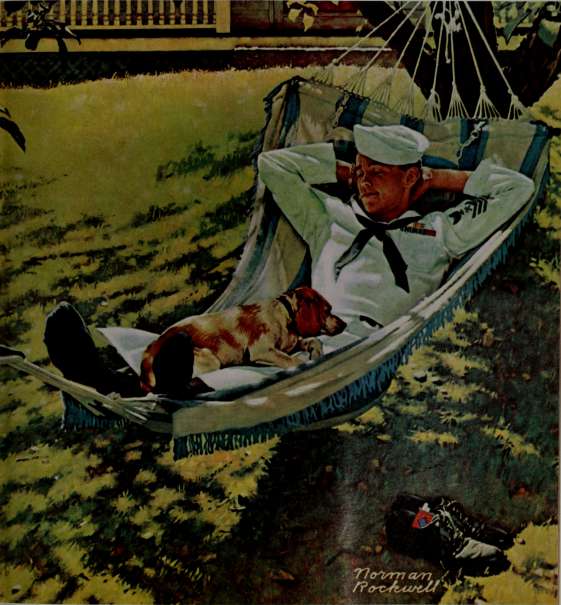

The Pursuits of Happiness

Haven't they always included the maintenance

of good health . . . and a little foolin' around with your

dog? For nearly a century, the American traditions

represented by Norman Rockwell's art have also been part

of the objectives of Miles. Generations of Americans

have enjoyed the whimsical depictions of family doctors

protecting the health of their neighbors. Characteristically

Rockwell had a serious thought underlying his whimsy.

These famous paintings are examples of the kindly

feeling of sacrifice and the extracurriculars practiced by

the medical profession. Founded by a doctor and

still headed by a doctor. Miles salutes the thorough, loving

physician portrayed in Rockwell's art . . . and the

good health theme that pervades his pictures.

IN/IILES

Elkhart, Indiana MANUFACTURER OF HEALTH CARE PRODUCTS SINCE 1884

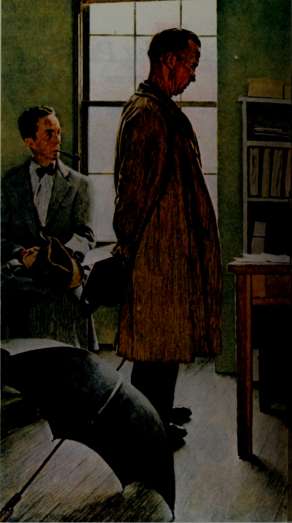

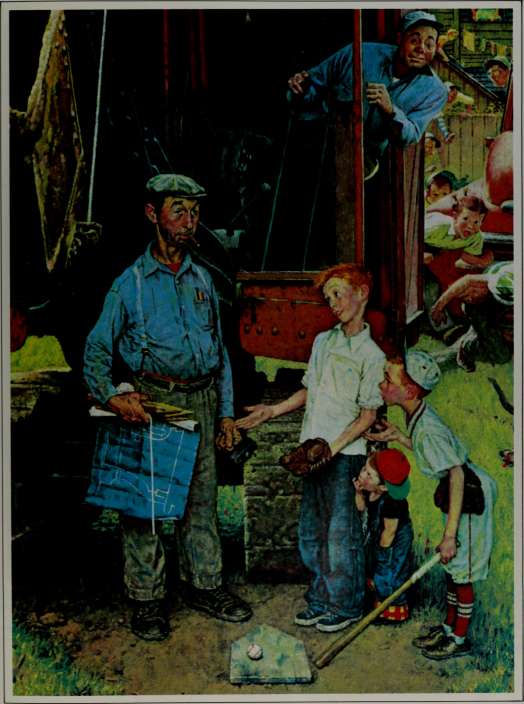

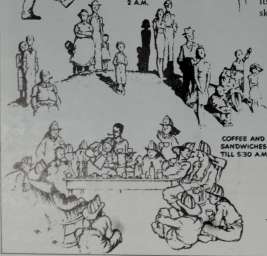

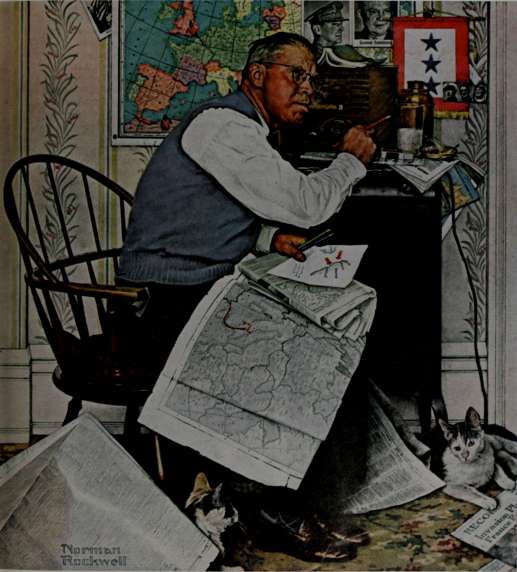

The Rockwell "visits" comprise a very special genre within the body of the man's work—they are his most literal depictions of American life.

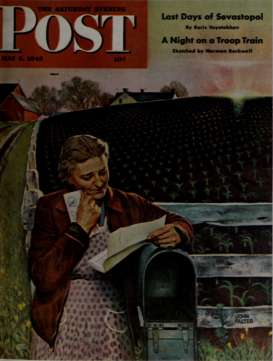

Everything in these pictures is what it appears to be. The teacher is a real teacher; the editor is a real editor. The nervous men waiting outside the maternity ward? They were all real fathers by the time their pictures appeared in the Post. On shoes, the patina of actual wear; on umbrellas, evidence of actual weather. The backgrounds show the places where flesh-and-blood people went about their daily tasks—real places furnished with real calendars and real telephones that could connect you with a place called "Central" when you lifted the receiver.

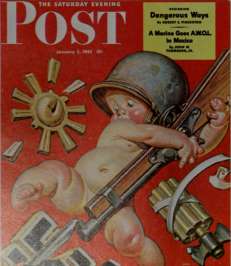

The paintings and drawings in this series were done on assignment for XhtPost between 1944 and 1948. The home front of World War II and the postwar years as America neared the midpoint of the century—here are glimpses of that world, preserved for a later generation's scrutiny.

These worthy citizens determined who was

entitled to extra quantities of such war-scarce

commodities as gasoline and sugar.

Kodiwell Visits a Ration Board

Spring was on the land, and the benignant Vermont sun, having penetrated every other nook and cranny in the town of Manchester, presently made its way into a certain quiet room where six men and one woman sat around a long, plain table. Then, in the following order, came: the song of birds, the fragrance of flowers, and-Norman Rockwell.

The last of these three, it developed, wanted something. The ration board, never having had a visitor who didn't, evinced no surprise. In Rockwell's caie, how-

ever, the desideratum was none of the things that the rest of us try to wheedle out of our ration boards.

"What I would like," said America's favorite artist, "is the privilege of painting pictures of all you board members."

Could it have been a glow of pleasure, the stirring of some long-suppressed vanity, that seemed momentarily to illumine the seven faces? After all, New Englanders are human. And when Rockwell paints you, the world sees you. At any rate, the board members consulted one another, reached a decision, and in unison nodded to the artist.

"But make us look good, now."

In a flash, Rockwell saw his advantage. Living in New

HATIONiN('

onncu

■I ■I

y

\>lJl

.\

il tfti

41 rjft ^•

^ ^

.i■M"^

England sharpens a man, brings out the trader in him.

"If I do," he bargained, "will you give me a B card?"

"No, but if you don't," they said, "we'll take away your A card."

In a flash, Rockwell took a back seat (the same one you see him occupying) and, his favorite pipe in his mouth, spent all day—a day of sunshine and showers-watching America parade by.

It was a parade that has been and still is going on all over the Union; a parade which differs from all other parades in this: Everybody marches in it. That is why it interested Rockwell. It is an integral part of the American scene—now. There was no such thing a few years ago, and who can say how soon our ration boards will

disband and tliis unique parade vanish forever? But no matter; for Rockwell has recorded the scene—the ration board at work and the importunate citizens who appear before it.

That record, reproduced here, is the newest chapter of a book which has been in the making for 28 consecutive years. The book might well be entitled Norman Rockwell's History of the U.S.A. It contains no text, and needs none. To leaf through its pages is to know America as it was—how its people looked and acted, how they dreamed and mourned and grinned— between the years 1915 and 1944.

Other chapters will be added to this record from time to time. Many of them, we trust. (1944)

Fala pursues as President Franktin D. Roosevelt's lunch is wheeled into his office.

White House correspondents interviewing a visiting Navy hero.

So You Want to See the President

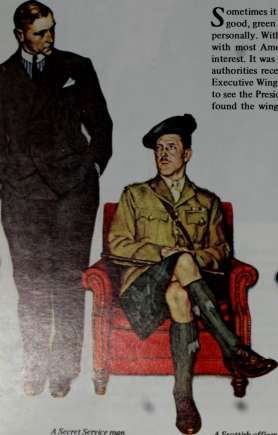

Sometimes it seems to the busy White House staff as if everybody on this good, green hemisphere wants to see the President of the United States personally. With a small segment of our population this is a chronic disease; with most Americans it is simply an expression of honest curiosity and interest. It was with this understandable interest in mind that White House authorities recently permitted Post artist Norman Rockwell to roam the Executive Wing and make a visual report on what the process of getting in to see the President is like. As the drawings and paintings show, Rockwell found the wing a fascinating antechamber of democracy, and he says he

A Secret Service man seeing all, as usual.

A Scottish officer on a military mission.

The Boss sees all he can, but some get turned away, which is probably the fate of this beauty and her cameraman.

Lieutenant General Stil-well, of Burma fame, is welcomed by the President's military aide. Major General Edwin M. (Pa) Watsoru (Right) Photographers waiting outside the Executive Wing Entrance for a newsworthy face.

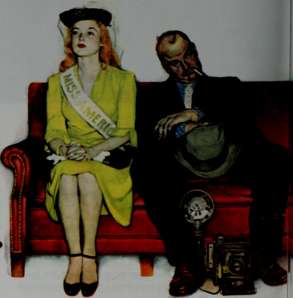

couldn't imagine such an atmosphere of dignified informality prevailing just outside the sanctum of a dictator or king. The waiting facilities are comfortable and easy on the eye. The secretarial staff is cheerful and courteous; so are the omnipresent Secret Service men, who manage to protect the President from possible harm with Gestapo-like efficiency, but without shoving anyone around. Conversation among the callers is subdued in tone but uninhibited. The White House newspaper correspondents go about freely—buttonholing heroes, legislators, beauty contest winners, and ambassadors, and doing their own invaluable job of keeping America in touch with its main listening post. The atmosphere is, on the whole, neighborly and friendly. Your trip through the anteroom of The Boss, as the staff speaks of him, awaits you in these pages. (1943)

Senators Connally (D., Texas) and Austin (R., Vermont) and briefcase.

What has Miss A merica go t that Wave Ensign Eloise English hasn 'tgot?

Another Secret Service man keeping both eyes peeled. ' i

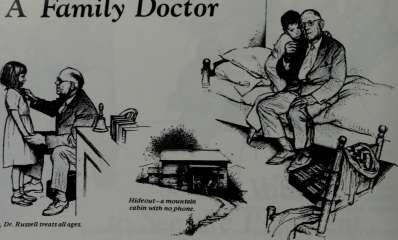

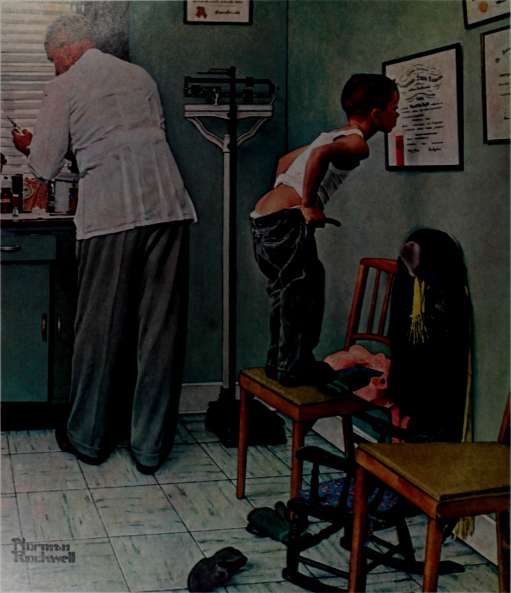

A Family Doctor

As school doctor. Dr. Russell treats all ages.

An Arlington man put it . like this: "We couldn't do without Doctor Russell. He's one man the town couldn't spare. For 33 years—he spent three overseas in World War I—he has dosed, bandaged, and spUnt-ed us, put the accident victims together, delivered the babies, treated the measles and mumps, and stitched up the town's cuts."

Dr. George A. Russell was the Rockwell family physician during the Vermont years. These sketches were made for a 1947 Post feature called "Norman Rockwell Visits a Family Doctor."

It may be bad news: "One more day like this and you can go back to school'

His collection of historical material fills four rooms.

Prescription for relaxation: Aq. Fluv. (river water), trout.

Waiting room. His office is part of a fine old house on the main street.

Since 1955 Crest has helped over 40 million kids prevent cavities.

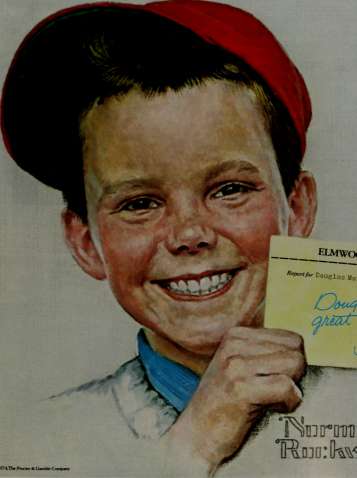

aMWOODCENTER

Report for Dou^ln- ■/„„ ""

''°^^"'^ Sept. 30. 1955

'MojorlW/cpflD

OI97<Thc PiDCKr A GaiUc Conpnr

Over 19 years ago Crest toothpaste because there have been over 20 clinical on treats.Take them to the dentist every

with fluoride was introduced. And since studies proving it The kids who have been six months for a regularcheckup and have

then. Crest has helped over 40 million kids helped by Crest know it works because them brush regularly with a fluoride

prevent millions and millions of cavities. they have the good checkups to prove it toothpaste you know you can trust Have

We know Crests fluoride works So make sure your kids cut down them brush with Crest

We know Crests Huonde works bo make sure your kids cut down

Why trust your family's teeth to anything else?

^^^"Cresf Kas been shown lo be on effective decoy-pf e ve n tiv e dentifrice fftot con be of s^nificonf volue wfien used m o conscientiously opplied l^^j progrom of orol hygiene and regular professtonol core" Council on Oentol Theropeutics. Amer<bn Dental AuocKihon-

]Cre$t-2^

You can't beat Crest for fighting cavities.

The Narrative Element in Painting

by E X. O' Connor

Norman Rockwell belongs to the great tradition of storytelling art. The story, like music, is a universal language. Home, family, happiness, tragedy—these transcend tongue.

Coming upon a mosaic floor in the ruins of Pompeii or a wall painting of the year 13,000 B.C. in the caves at Lascaux, we recognize the unchanged human condition; we recognize ourselves though we do not know the words of the cave man, or even the Latin of Pompeii.

The scraps on the floor in the mosaic worked out in tiny pieces of stone and glass are today's garbage, familiar to any housewife or husband who has been admonished to carry out the trash. Even the family dog would recognize the mosaic's chicken bones. The animals on the walls of Lascaux still spur the hunting instinct in man, still point to our fears of psychological dangers in a dark and unknown world.

Rockwell knows how to make a story plain and simple and yet fill it

with the complex emotions that speak universally to man. As a narrative painter, he has a firm grasp on the obvious. To the despair of magazine editors who were pressed by deadlines, Rockwell liked to ask his neighbors, strangers in the street, anybody, what they thought of his pictures, if they understood them. "If they don't understand the story I'm trying to tell, I figure I haven't made it clear enough and that a lot of other people around the country won't un-

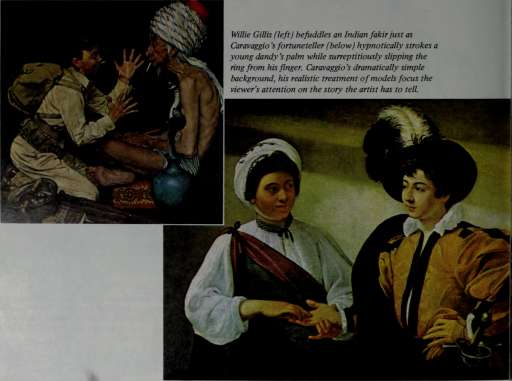

Willie Gillis (left) befuddles an Indian fakir just as Caravaggio 's fortuneteller (below) hypnotically strokes a young dandy's palm while surreptitiously slipping the ring from his finger. Caravaggio's dramatically simple background, his realistic treatment of models focus the viewer's attention on the story the artist has to tell.

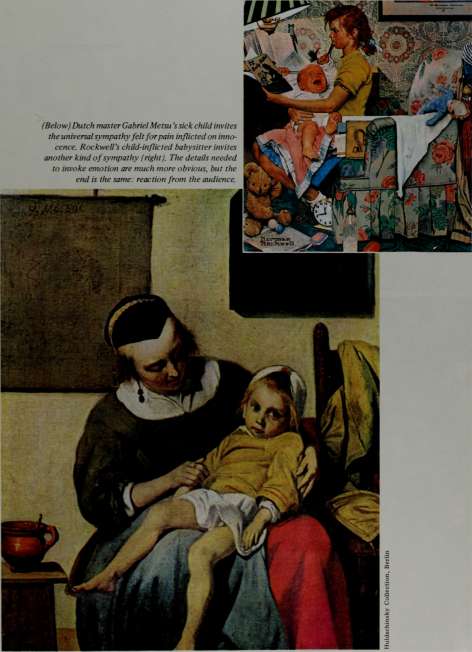

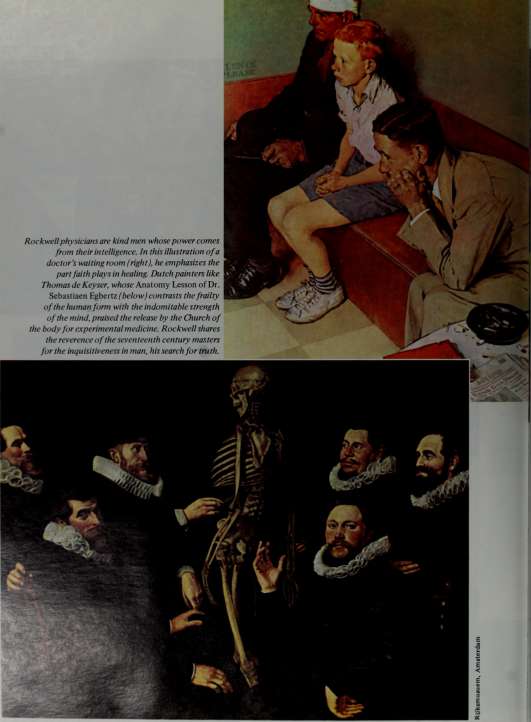

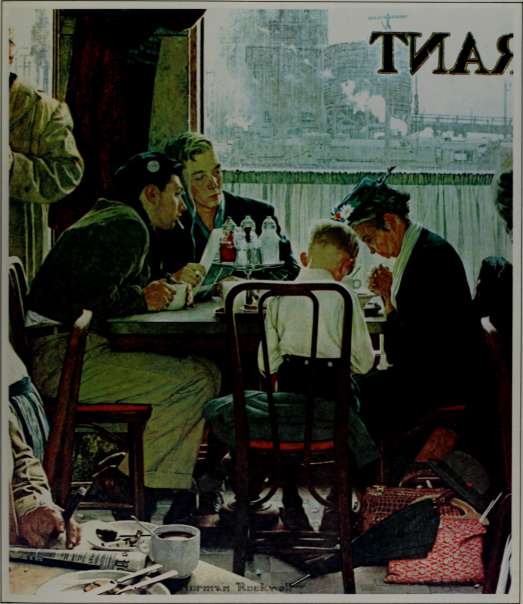

Rockwell physicians are kind men whose power comes

from their intelligence. In this illustration of a

doctor's waiting room (right), he emphasizes the

part faith plays in healing. Dutch painters like

Thomas de Keyser, whose Anatomy Lesson of Dr.

Sebastiaen Egbertz (below) contrasts the frailty

of the human form with the indomitable strength

of the mind, praised the release by the Church of

the body for experimental medicine. Rockwell shares

the reverence of the seventeenth century masters

for the inquisitiveness in man, his search for truth.

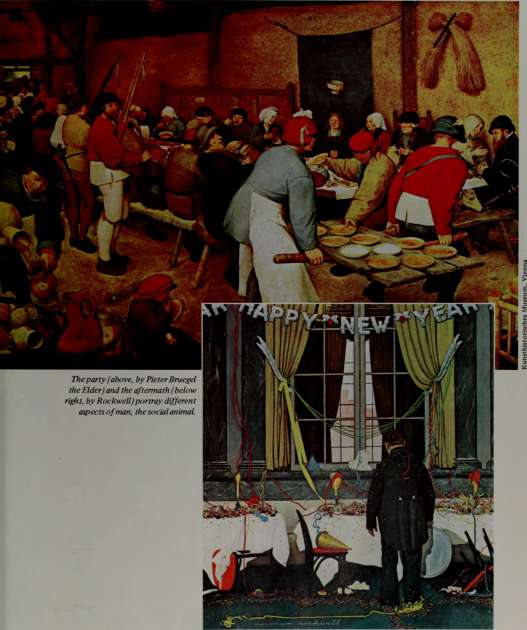

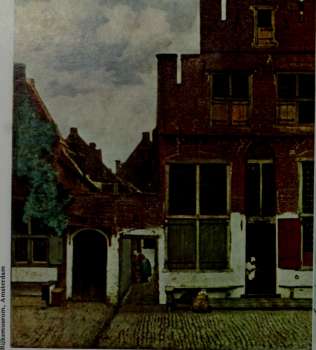

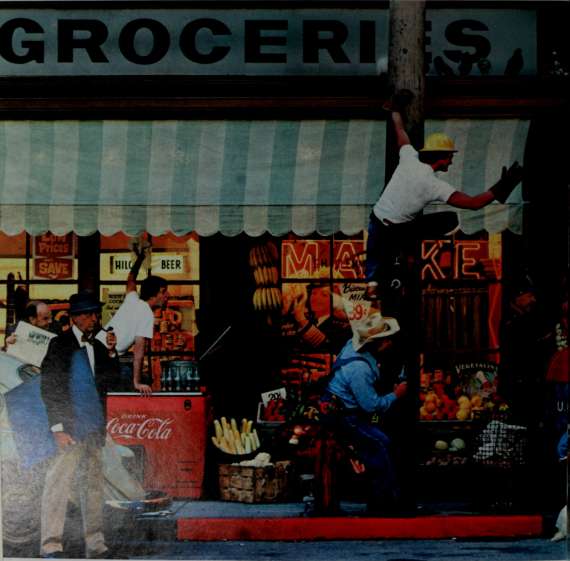

Vermeer 's seventeenth century view of Delft (left) and Rockwell's imagined frieze of eighteenth century Philadelphia shops become almost still lifes of carefully observed objects and activities. Nearly 300 years separate the two city scapes, but the artist still finds man, at work or play, a cherished creature whose comings and goings will always be worth recording.

r

^x^

..^/

^i4^i^rtVt.^1

derstand it either." And then he would change the paintings to accomodate public opinion.

Rockwell painted for the millions, a more difficult audience than the few. Giotto and early Italian Renaissance painters understood the value of a large audience. So did seventeenth century Dutch

genre painters and the pre-Rapha-elites. Commissions might come from anywhere. The more who saw and understood, the greater the artist's success as a narrator of the spirit and the earthly climate of his day. In that sense Rockwell has been an immense success. Worldly power counted for nothing with

him, but he would've considered himself a failure had people not understood his observations, his duty to create positive values. Rockwell leaves historical documents of a people during the crises of depression and world war. He was aware of death, but for him, life was a stronger force.

Famous Faces

He painted the great as well as the humble—Presidents and potentates along with newsboys and bums, glamorous actresses and First Ladies as well as charwomen and little girls with skinned knees.

Among those who sat for Rockwell portraits: Ethel Barrymore and Jennifer Jones, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Gary Cooper, Frank Sinatra, Arnold Palmer, Stan Musial, Joe Garagiola, four Presidents, a half-dozen unsuccessful candidates for that office (and their wives), plus assorted astronauts and a few foreign heads-of-state.

Was he awed by all these persons

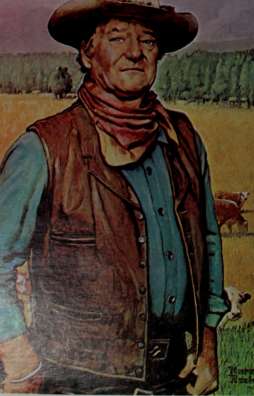

Funnyman Jack Benny (below) looks wise, witty, and everlastingly 39 in this 1963 portrait, while character actor Walter Brennan (right) gazes out at a long gone West, a West of men with nature as their only friend, a land of honesty, where character was as big as the space.

of prominence and power?

Always, said Norman Rockwell in his autobiography. He insists that he suffered from a kind of stage fright when confronted with a famous face. The truth is, some of the important people who sat for their portraits were very much in awe of Norman Rockwell, who was, by the late '50's, an American institution.

N.R. first dipped his paintbrush into the political scene in 1952, when the Post sent him to Denver to paint newly nominated Presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower.

"Likable and charming," Rockwell said of Adlai Stevenson, Eisenhower's opponent in the Presidential election of 1956. In an attempt to be impartial the Post ran Rockwell portraits of the two candidates on consecutive issues just before Americans went to the polls.

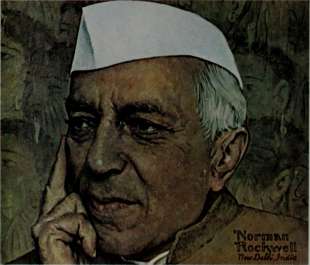

(Above) "I wanted a profile shot of Nasser, "Rockwell said. "But he kept giving me that handsome wide-toothed grin." Bodyguards didn 't help make the posing session any easier. Finally, the skinny artist jumped up and bodily turned Egypt's husky President sideways. Bob Hope's ski-slope nose, his wisecracking eyes almost spit out snappy one-liners in the 1954 portrait at right. Nehru, (below) agreed to wear his white linen hat though it was winter when Rockwell flew to New Delhi. The Nasser and Nehru portraits appeared on the Post in 1963.

Ike asked Rockwell's advice about his own painting, and at the end of the sitting they were good friends.

Four years later Rockwell painted Ike again, and he also painted Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson.

"Painting both candidates didn't exactly clarify my political views because, as it turned out, Governor Stevenson was very likable and charming, too."

You would have to believe, from their Rockwell portraits, that all famous people are "likable and charming."

There is, of course, an explanation.

Rockwell saw the best in the people he painted, and he painted that "best"-the warmth, the

iSoirino»voii

humor; the smile lines and the twinkle in the eye; the modesty and wisdom.

Rockwell liked the people he painted, and they liked him, and this mutual respect and affection adds a very special quality to these portraits of Presidents, statesmen, political figures, and show biz personalities.

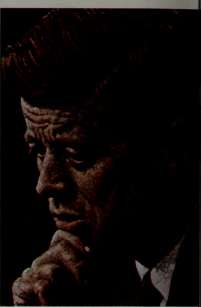

Big John Wayne barely fits in the canvas (below); the actor's sequoia-like grandeur dwarfs cattle and prairie alike. To the right and below, two fi'om the series of Presidential portraits Rockwell painted for the Post Most pictures of John F. Kennedy emphasize the man's youth and vigor rather than the intellectual qualities inherent in the Rockwell portrait that appeared on the magazine cover in April 1963. Dwight Eisenhower was the first President Rockwell painted for the Post "It's his range of expression that's so appealing, "Rockwell wrote, explaining why he called Ike one of his favorite models; "his wide, mobile mouth and expressive eyes."

*^>TK-^/^^j^

■^f^

IRsdw/all I

GEE WHIZ!

GREETING CARDS, NOTES AND SATURDAY EVENING POSTers

featuring 70 of Norman Rockwell's most popular Post covers. Now available from your favorite greeting card shop.

Box 9500

Boulder, CO 80301 (303)530-1442

Illustration Z 1938 The Curtis Publishing Co.

LEANIN'MTREE

Rockwell Cards Are

Published Exclusively

By Leanin' Tree

C1978 Leanin Tree Publishing Co.

Norman Rockwell Paints Norman Rockwell

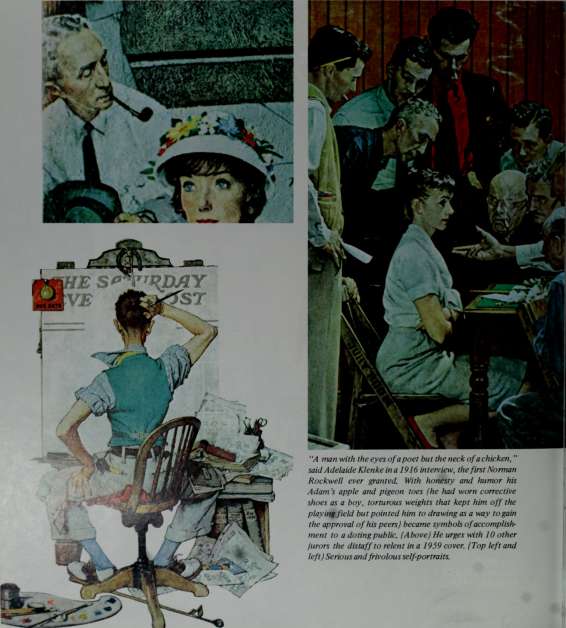

"A man with the eyes of a poet but the neck ofachicken," said Adelaide Klenke in a 1916 interview, the first Norman Rockwell ever granted. With honesty and humor his Adam's apple and pigeon toes (he had worn corrective shoes as a boy, torturous weights that kept him off the playing field but pointed him to drawing as a way to gain the approval of his peers) became symbols of accomplishment to a doting public. (Above) He urges with 10 other jurors the distaff to relent in a 1959 cover. (Top left and left) Serious and frivolous self-portraits.

The artist's face needs no exaggeration, unlike most of his models, whose teeth (below) have to be bared to show their happiness in a homecoming cover of the '40's. In Blacksmith's Boy, Heel and Toe (above) the poetic eyes smile to bring the viewer into the contest, while (right) the painter turns actor to play two parts-first listener and then speaker-in the famous Gossips cover.

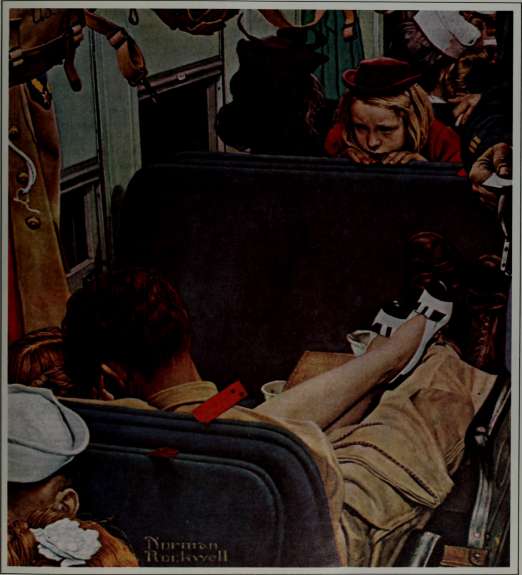

Every day, across the length and breadth of the land, this scene is repeated in 14,000 American cities and towns.

Greyhound buses take more Americans home than anybody else on earth. Or in the sky.

But, Greyhound's sen/ice to America doesn't stop there.

Greyhound's Armour is America's number one producer of bacon and number two in sales

Wa'reasbasictoAmeticaasasmaHtown

^. ^ ^^ .-r^mt^.

of hot dogs.

Greyhound's Dial is the nation's best-selling soap, and our Tone brand is one of the most successful new soaps in a decade.

Greyhound Food Service feeds nnillions of Americans daily under contracts with everybody from the Air Force at Lackland to the work force at General Motors.

Plus, Greyhound leases trains to the

railroads and jumbo'jets to the airlines. We rent cars, write insurance, finance computers, fuel aircraft, build display booths and generally do everything from hosting Las Vegas conventions to spinning yarn for Grandma's shawl.

In short. Greyhound isn't just "the bus company" anymore; it's "the omni bus company"— a$4-billion, diversified corporation ser\/ing America in a hundred basic ways.

MIS slop.

Greyhound Corporation The omnibus company.

Parade of Hits

Rock well made the Post cover a museum for the country's moral yearning. Good and good times are crystallized into the reality of the American dream.

flomiftn

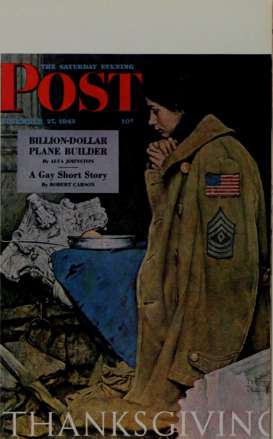

"The little lady is a quiet sermon in paint. " a Post editor wrote when this Thanksgiving cover first appeared. "She gives thanks that she is alive, that she has America to be alive in, and that she has God for herself and America to lean upon today and all the days. " (November 24,1951)

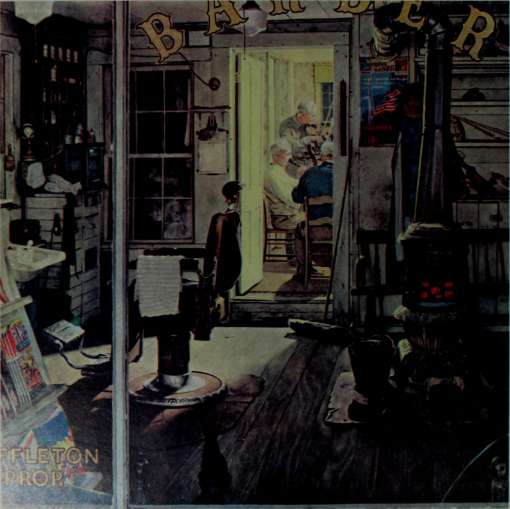

Longhair music from the backroom of an establishment devoted to shortening hair. The Rob Shuffleton who was Rockwell's barber in Arlington was also a cellist who regularly played host to musical friends after business hours, fApril 29,1950)