Dennis crosses the Ohanapecosh River suspension bridge to access the Grove of the Patriarchs—the same bridge that was severely damaged in the November 2006 floods.

Introduction

Mount Rainier stands as the most recognizable feature in Washington's diverse landscape. At 14,411 feet, this mighty mountain towers nearly 8000 feet over its neighboring peaks, which makes it visible from nearly every corner of the state. The mountain has been a standard feature of Washington's history well before it was “discovered” by Captain George Vancouver. Native tribes on both sides of the Cascades, as well as those living far south in present-day Oregon, included the mountain in their stories and legends.

But though the mountain's presence has been a constant throughout human history in the region, that presence has also been an ever-changing one. Mighty Mount Rainier is, after all, an active volcano and, more importantly (on a human scale, at least), it's an imposing geologic feature whose sheer size and prominence not only attracts strong weather systems but also helps create wild weather. This is important for recreationists to keep in mind. Despite what your schoolteachers may have taught, geologic change isn't so much a matter of slow, steady change. Rather, it's like a war: long, boring periods of calm are broken by random moments of extreme activity, sheer chaos, and ruin.

The latest of these chaotic moments occurred during November 2006. Record rainfall and gale-force winds wreaked havoc on the environs of Mount Rainier National Park, changing the courses of rivers, toppling acres of trees, moving mountains of mud, and destroying a great deal of the man-made structures within the national park. Roads were washed out, bridges and footlogs swept away, trails blocked by windfalls, and even destroyed one entire campground—Sunrise Camp, which was swept away by the raging Nisqually River. Even as this book is being completed, we still don't know when all the extensive damage done by those early winter storms will be repaired. We do know most trails are open, though sections may be very rough for the next few years.

Still, hikers should understand that trails aren't static features on the ground. Time and weather do bring changes—sometimes quickly and dramatically. By understanding that, and accepting route changes and obstacles as they come, hikers can rest assured that their trail adventures will be outstanding in this wonderful wild country.

Mount Rainier National Park offers some of the most spectacular and diverse backcountry found in this nation. Wilderness enthusiasts from Bob Marshall to John Muir have praised the beauty and unique splendor of the park's meadows, forests, and glacier basins. Muir called Rainier's array of wildflower meadows the most superb subalpine gardens he had ever encountered. The park sports vast fields of flower parklands, from the broad, sloping fields of Spray Park to the gaudy colors that fill the cirque of Indian Bar Camp, to the huge, flat, mountaintop meadow of Grand Park. In addition to the meadows, there are more than one hundred waterfalls within the park (some estimates run as high as 162 falls)—fifty-two of which are prominent enough to warrant names. You'll also find nearly three hundred lakes and more than one hundred named peaks within the park. Finally, the park has one of the world's largest glacier systems found on a single peak. About 9 percent of the total park surface is covered in glacial ice. There are twenty-seven individual glaciers and fifty permanent snowfields within the park. All told, snow and ice permanently covers more than 22,000 acres of land.

In short, Mount Rainier National Park offers more than grand views of the mighty mountain. Many of the hikes you'll find in this book provide few, or no, views of the big mountain itself, yet all offer incredible scenery and wonderful wilderness exploration.

THE MOUNTAIN'S HISTORY

Before it was Rainier, this grand mountain was known to local tribes as Tahoma (or one of many variations of this name), which reportedly means “breast of milk-white waters” or perhaps simply “great white mountain.”

This latter meaning seems most likely, since it was also a description used independently by early European explorers. Indeed, the first account of the mountain, by Captain George Vancouver, describes Rainier as “the round snowy mountain…” The mountain was formally “discovered” by Vancouver while his ship lay at anchor near what is now Port Townsend. From his ship's deck, he sighted the big, snowcapped peak on the southeastern horizon. On May 8, 1792, Vancouver wrote in his journal entry about the sighting:

“The weather was serene and pleasant, and the country continued to exhibit, between us and the eastern snowy range, the same luxuriant appearance. At its northern extremity, Mount Baker bore by the compass N22°E; the round snowy mountain, now forming its southern extremity and which, after my friend Rear Admiral Rainier, I distinguish by the name of Mount Rainier, bore N(S)42°E.”

Since that first written description, Mount Rainier has captured the hearts of men and women who ventured out to the wild Washington Territory. In 1849 the United States established Fort Steilacoom near present-day Tacoma, to help protect settlers against Indians who fought the loss of their lands. Following the Indian War of 1855, areas beyond the Puget Sound lowlands were open for greater exploration. In 1857 a young lieutenant from Fort Steilacoom decided to try for the summit of the mountain that dominated the eastern skyline. Lt. A. V. Kautz set out with an army surgeon from Fort Bellingham, four soldiers, and a Nisqually Indian guide. The Kautz party failed in its summit bid but did get farther up the mountain than any other American party. Kautz Creek along the southwestern side of the mountain still bears the lieutenant's name.

The next recorded summit attempt occurred thirteen years later. This time, Hazard Stevens and P. B. Van Trump successfully summitted on August 17, 1870. James Longmire served as a pack master on that trip, helping get Stevens and Van Trump to the base of the mountain. Another thirteen years would pass before Longmire himself summitted in 1883, with Van Trump, and on their return from the top, they discovered the meadows and hot springs of what is now the Longmire area .

Longmire returned to the area and established a hotel and spa at the hot springs, launching the tourism business that grew around the southwest corner of the mountain. As more and more people discovered the splendor of this remarkable mountain, the move to preserve the mountain was born.

In 1893 President Benjamin Harrison created the Pacific Forest Reserve, which included much of what is now Mount Rainier National Park and the adjacent national forestland. Four years later, Present Grover Cleveland signed an order changing the name to the Mount Rainier Forest Preserve, and on March 2, 1899, President William McKinley signed into law the establishment of Mount Rainier National Park—just the fifth national park in the United States. (The other four were Yellowstone National Park, 1872; Sequoia National Park, 1890; General Grant National Park, 1890; and Yosemite National Park, 1890. In 1940 General Grant National Park was incorporated into Kings Canyon National Park.)

As a national park, Mount Rainier received a great deal of attention. Roads were built to help guide visitors to some of the most remarkable portions of the park. In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) began their efforts, and much of their work still stands today. Indeed, Mount Rainier National Park holds one of the great collections of intact and still functioning CCC projects in the country. The CCC built things, from lodges to trails, to last. Many of the rock walls lining the road to Paradise were made by CCCers—the intricate rock work is best viewed at the Narada Falls parking area.

Not all the developments were beneficial, though. Through the 1920s, '30s, and '40s, the Paradise area was overrun by tourists. The beautiful meadows were buried every summer under cities of tents. There was even a golf course set up in the meadows. Those campsites, putting greens, and car parks were all removed in later years, fortunately, and the glorious meadows were restored to their native beauty. Similar overdevelopment and subsequent return to nature occurred in the Sunrise area—though the golf course there was much smaller!

Today, some park visitors bemoan the “overdevelopment” of the backcountry. The lower trails near Paradise are paved, and other trails are generally broad and well maintained. Backpackers are restricted, for the most part, to established backcountry campsites. But the country is still wild, the trails can still be rough and even treacherous, and the scenery is as spectacular as it was when Vancouver first sighted the big mountain more than two hundred years ago.

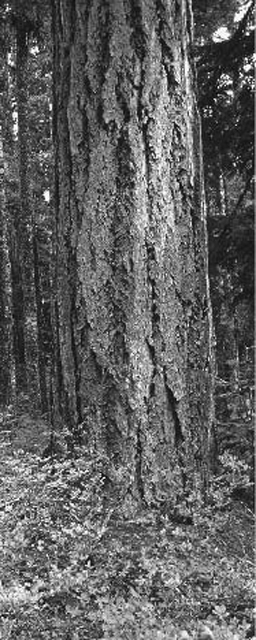

Douglas fir along the trail above Chinook Creek on the way to Owyhigh Lakes

USING THIS BOOK

These Day Hiking guidebooks strike a fine balance. They were developed to be as easy to use as possible while still providing enough detail to help you explore a region. As a result, these guidebooks include all the information you need to find and enjoy the hikes, but they leave enough room for you to make your own discoveries as you venture into areas new to you.

What the Ratings Mean

Every trail described in this book features a detailed “trails facts” section. Not all of the details here are facts, however.

Each hike starts with two subjective ratings: each has an overall rating of one to five stars for its overall appeal, and each route's difficulty is rated on a scale of 1 to 5. This is subjective, based on the author's impressions of each route, but the ratings do follow a formula of sorts. The overall rating is based on scenic beauty, natural wonder, and other unique qualities, such as solitude potential and wildlife-viewing opportunities.

| ***** | Unmatched hiking adventure; great scenic beauty and wonderful trail experience! |

| **** | Excellent experience sure to please all. |

| *** | A great hike, with one or more fabulous features to enjoy. |

| ** | May lack the “killer view” features but offers lots of little moments to enjoy. |

| * | Worth doing as a refreshing wild-country walk, especially if you are in the vicinity. |

The difficulty rating is based on trail length, the steepness of the trail, and how strenuous it is to hike. Generally, trails that are rated more difficult (4 or 5) are longer and steeper than average. But it's not a simple equation. A short, steep trail over talus slopes may be rated 5, whereas a long, smooth trail with little elevation gain may be rated 2.

5 Extremely difficult: Excessive elevation gain, and/or more than 6 miles one-way, and/or bushwhacking required.

4 Difficult: Some steep sections, possibly rough trail or poorly maintained trail.

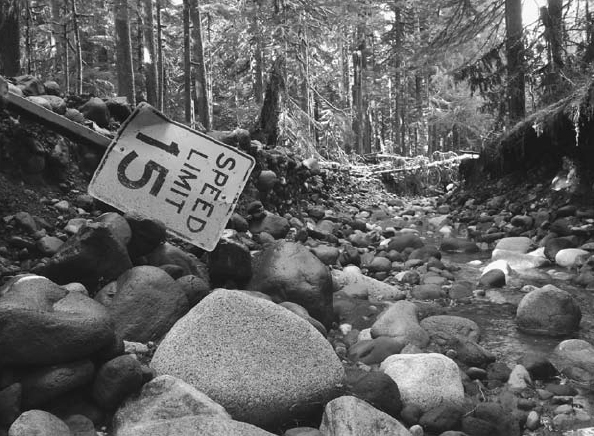

Always check for flood damage: the Carbon River Road in December 2006.

3 Moderate: A good workout, but no real problems.

2 Moderately easy: Relatively flat or short, with good trail.

1 Easy: A relaxing stroll in the woods.

To help explain how those difficulty ratings were arrived at, you'll also find the following information:

Round-trip mileage: The distances given are not always exact mileages (round-trip unless otherwise noted as one-way)—trails weren't measured with calibrated instruments—but the mileages are those used by cartographers and land managers (who have measured many of the trails).

Elevation gain: The elevation gains report the cumulative difference between the high and low points on the route—in other words, the total amount you will go up on a hike (given in feet).

High point: It's worth noting that not all high points (also given in feet) are at the end of a trail—a route may run over a high ridge before dropping to a lake basin, for instance.

Season: Many trails can be enjoyed from the time they lose their winter snowpack right up until they are buried in fresh snow the following fall. But snowpacks vary from year to year, so a trail that is open in May one year may be snow-covered until mid-July the next. The hiking season for each trail is an estimate, but before you venture out, it's worth contacting the land manager to get current conditions.

Profiles: Each hike's relative elevation changes are shown in feet over the hike's mileage—usually one-way.

Maps: The maps you'll want to have on your hike are listed next. Hikes in this guidebook typically reference Green Trails maps, which are based on the standard 7.5-minute U.S. Geological Survey topographical maps. Green Trails maps are available at most outdoor retailers in the state, as well as at many National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service visitor centers.

Contact: Here you'll find phone and web information for each trail's governing agency so you can get current trail conditions.

Notes: Next are quick notes, in some cases, that might be pertinent to your planning, such as annual road closures or trail restrictions.

GPS coordinates: For each trailhead, the GPS coordinates are provided—use this both to get to the trail and to help you get back to your car if you get caught out in a storm or wander off the trail.

Following these detailed “trail facts,” the route descriptions themselves provide a basic overview of what you might find on your hike, directions to get you to the trailhead, and in some cases additional highlights beyond the actual trails you'll be exploring.

Icons and trail introduction: This is a quick overview of what each trail has to offer, including icons to help you quickly determine the following:

kid-friendly

kid-friendly

dog-friendly (Note: This icon seldom appears in this book because dogs are prohibited on all trails within Mount Rainier National Park except on the Pacific Crest Trail.)

dog-friendly (Note: This icon seldom appears in this book because dogs are prohibited on all trails within Mount Rainier National Park except on the Pacific Crest Trail.)

![]() wildlife viewing

wildlife viewing

historic

historic

exceptional views

exceptional views

views of waterfall(s)

views of waterfall(s)

endangered trail

endangered trail

saved trail

saved trail

A world of glacial ice peeks through the clouds.

Getting there: Directions to the trailhead are from the nearest large town or geographic location or feature.

On the trail: Detailed descriptions of the hiking route tell you some of the things you might find along the way, including geographic features, scenic views, potential flora and fauna, and more.

Extending your trip: For those looking to go farther and do more than the recommended outing, details are provided on how to add miles or even days to the hike. You might also find brief descriptions of additional trail miles and/or camping options.

Of course, even with all of this, you'll need some information long before you ever leave home. So as you plan your trips, consider the following several issues.

PERMITS, REGULATIONS, AND PARK FEES

You can't set foot out your door these days without first making sure you're not breaking the rules. In an effort to keep our wilderness areas wild and our trails safe and well maintained, the land managers—especially the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service—have implemented a sometimes complex set of rules and regulations governing the use of public lands.

Within Mount Rainier National Park, the system is fairly simple. To enter the park at one of the main gateways (Nisqually Entrance, Stevens Canyon Entrance, White River Entrance, or Carbon River Entrance), you'll pay a vehicle entry fee of $15 for private noncommercial vehicles or $5 per visitor on foot, bicycle, or motorcycle. The fee provides access for seven days. Frequent visitors can opt instead for an annual pass for $30—this pass covers the entry fee for the pass holder, the pass holder's vehicle, and any passengers. Day hikers require no other permit, though backpackers will have to pick up a free wilderness camping permit from any of the park's ranger stations.

WEATHER

Mountain weather in general is famously unpredictable, but Mount Rainier's 8000-foot prominence over its neighboring peaks makes it a magnet for extreme weather. The big peak stretches up so far above the surrounding Cascades that it captures weather that streams over the top of the lesser mountains. As a result, Mount Rainer can host howling blizzards in July and torrential downpours in August. The mountain recently lost its standing as “snowiest place on earth” to Mount Baker to the north, but the mountain regularly records nearly 1000 inches of snow per year. (The record for annual snowfall is 1140 inches, set at Mount Baker during the winter of 1998–99. Prior to that year, Mount Rainier held the record, with 1122 inches.) One of the reasons for the big annual accumulations is the tendency for snow to fall periodically throughout the year. As I researched the routes for this book, I experienced snowfall during every month of the year. So prudent hikers must plan for extreme weather, even if they're heading out on just a short day hike. (See also “Mount Rainier: The Weather-Maker” in the Longmire section).

But unexpected rain and snow is just part of the story. During the summer months, when the warm air of the lower Cascades rises up and hits the cool, moist air surrounding the upper slopes of Rainier, thunderstorms can develop quickly. Hikers must be aware of this potential because thunderstorms can develop very quickly, with little warning, and a hiker stuck high on the mountain's flanks becomes a good target for a lightning bolt (see “All Lit Up” for how to avoid this).

ROAD AND TRAIL CONDITIONS

Trails in general change little year to year. Though they truly are man-made structures in rugged wilderness settings, trails are quite durable. But change can and does occur, and sometimes it occurs very quickly. One brutal storm can alter a river's course, washing out sections of trail in moments. Wind can drop trees across trails by the hundreds, making the paths unhikeable. And snow can obliterate trails well into the heart of summer.

ALL LIT UP

The following are suggestions for reducing the dangers of lightning should thunderstorms be forecast or develop while you are in the mountains:

• Use a NOAA weather radio (a radio tuned in to one of the national weather forecast frequencies) to keep abreast of the latest weather information.

• Avoid travel on mountain tops and ridge crests.

• Stay well away from bodies of water.

• If your hair stands on end or you feel static shocks, move immediately—the static electricity you feel could very well be a precursor to a lightning strike.

• If there is a shelter or building nearby, get into it. Don't take shelter under trees, however, especially in open areas.

• If there is no shelter available and lightning is flashing, remove your pack (the metal stays or frame are natural conductors of electricity) and crouch down, balancing on the balls of your feet until the lightning clears the area.

Access roads face similar threats and, in fact, are more susceptible to washouts and closures than the trails themselves. For instance, the massive rains of November 2006 created unprecedented floods in the national park. Roads, trails, and even a campground washed away. The Carbon River Road and Cayuse Pass Highway (State Route 123) are especially prone to temporary closures due to flooding.

Because there really is no such thing as a flat trail in the Mount Rainier area, trails are susceptible to water damage, too. Trail treads erode, bridges and footlogs wash out, and windfall trees block routes after every large storm. Fortunately, repairs take place regularly, and for that we can thank the countless volunteers who donate tens of thousands of hours to trail maintenance each year. The Washington Trails Association (WTA) alone coordinates upward of 60,000 hours of volunteer trail maintenance each year in Washington State, and Mount Rainier National Park benefits from a good portion of that effort.

As massive as the volunteer efforts have become, there is always a need for more. Our wilderness trail system faces increasing threats, including (but by no means limited to) ever-shrinking trail funding, inappropriate trail uses, and conflicting land-management policies and practices.

With this in mind, this guide includes several trails that are threatened and in danger of becoming unhikeable. These “endangered trails” are marked with the special icon shown at the start of this paragraph.

With this in mind, this guide includes several trails that are threatened and in danger of becoming unhikeable. These “endangered trails” are marked with the special icon shown at the start of this paragraph.

On the other hand, we've also been blessed with some great trail successes in recent years, thanks in large part to that massive volunteer movement spearheaded by WTA. These “saved trails” are marked with the icon shown at the start of this paragraph. As you enjoy these saved trails, stop to consider the contributions made by your fellow hikers that helped protect our trail resources.

On the other hand, we've also been blessed with some great trail successes in recent years, thanks in large part to that massive volunteer movement spearheaded by WTA. These “saved trails” are marked with the icon shown at the start of this paragraph. As you enjoy these saved trails, stop to consider the contributions made by your fellow hikers that helped protect our trail resources.

WILDERNESS ETHICS

As wonderful as volunteer trail maintenance programs are, they aren't the only way to help save our trails. Indeed, these on-the-ground efforts provide quality trails today, but to ensure the long-term survival of our trails—and the wildlands they cross—we all must embrace and practice sound wilderness ethics.

Strong, positive wilderness ethics include making sure you leave the wilderness as pure as or purer than it was when you found it. As the adage says, “Take only pictures, leave only footprints.”

But sound wilderness ethics go deeper than that, beyond simply picking up after ourselves when we go for a hike. Wilderness ethics must carry over into our daily lives. We need to ensure that our elected officials and public land managers recognize and respond to our wilderness needs and desires. If we hike the trails on the weekend but let the wilderness go neglected—or, worse, allow it to be abused—on the weekdays, we'll soon find our weekend haunts diminished or destroyed.

TRAIL GIANTS

I want to add a personal note here. As I began my career as a guidebook author, I was blessed with the opportunity to learn from the men and women who helped launch the guidebook genre for The Mountaineers Books. Throughout the 1990s, I enjoyed many conversations with Ira Spring—we would talk for hours about our favorite trails and how we needed to diligently fight for those trails. I exchanged frequent correspondence with Harvey Manning, debating the best means of saving wildlands. I was advised and mentored by Louise Marshall. I worked alongside Greg Ball—founder of the WTA's volunteer trail maintenance program—for more than a decade.

Encroaching clear-cuts on the western national park boundary seen from the summit of Glacier View

In short, I served my apprenticeship with masters of the trail trade. From them, and from my own experiences exploring the wonderful wildlands of Washington, I discovered the pressing need for individual activism. When hikers get complacent, trails suffer. We must, in the words of the legendary Ira Spring, “get people onto trails. They need to bond with the wilderness.” This green bonding, as Ira called it, is essential in building public support for trails and trail funding.

As you get out and hike the trails described here, consider that many of these trails would have long ago ceased to exist without the phenomenal efforts of people such as Ira Spring, Harvey Manning, Louise Marshall, and Greg Ball, not to mention the scores of unnamed hikers who joined them in their push for wildland protection, trail funding, and strong environmental stewardship programs.

When you get home, bear in mind these people's actions and then sit down and write a letter to your congressperson asking for better trail funding. Call your local Forest Service office to say that you've enjoyed the trails in their jurisdiction and that you want these routes to remain wild and accessible for use by you and your children.

And if you're not already a member, consider joining an organization devoted to wilderness, backcountry trails, or other wild-country issues. Organizations including The Mountaineers Club, Washington Trails Association, Volunteers for Outdoor Washington, the Cascade chapter of the Sierra Club, Conservation Northwest, the Cascade Land Conservancy, and countless others (see the appendix at the back of this book) leverage individual contributions and efforts to help ensure the future of our trails and the wonderful wilderness legacy we've inherited.

TRAIL ETIQUETTE

Everyone who enjoys backcountry trails should recognize their responsibility to those trails and to other trail users. We each must work to preserve the tranquility of wildlands by being sensitive not only to the environment but to other trail users as well.

Share the Trails

The trails in this book are used by a very large number of hikers, as well as by other users, including climbers, trail runners, and horse riders (allowed only on some trails within the park). When you encounter other hikers and trail users, please follow the trail-tested rules of practicing common sense and exercising simple courtesy. It's hard to overstate just how vital these two things—common sense and courtesy—are to maintaining an enjoyable, safe, and friendly situation when different types of trail users meet. See “The Golden Rules of Trail Etiquette” for what you can do during trail encounters to make everyone's trip more enjoyable.

Where the road used to be: the Carbon River Road near Ipsut Creek Campground after the November 2006 floods

THE GOLDEN RULES OF TRAIL ETIQUETTE

Below are just a few of the things you can do to maintain a safe and harmonious trail environment. And while not every situation is addressed by these rules, you can avoid problems by always remembering that common sense and courtesy are in order.

• Yield right-of-way. When two or more hikers meet, the uphill hiker has the right-of-way. There are two general reasons for this. First, on steep ascents, hikers may be watching the trail and not notice the approach of descending hikers until they are face-to-face. More important, it is easier for descending hikers to break their stride and step off the trail than it is for those who have gotten into a good climbing rhythm. But by all means, if you are the uphill trekker and you wish to grant passage to oncoming hikers, go right ahead with this act of trail kindness.

• Move off-trail when yielding. When a hiker meets other user groups (such as bicyclists or horseback riders), the hiker should move off the trail. This is because hikers are more mobile and flexible than other users, making it easier for them to step off the trail.

• Step downhill when encountering horses. When a hiker meets horseback riders, the hiker should step off the downhill side of the trail, unless the terrain makes this difficult or dangerous. In that case, move to the uphill side of the trail, but crouch down a bit so you don't tower over the horses' heads. Also, make yourself visible so as not to spook the big beasties, and talk in a normal voice to the riders. This calms the horses. If you're hiking with a dog, keep your buddy under control.

• Stay on trails and practicing minimum impact. Don't cut switchbacks, take shortcuts, or make new trails. If your destination is off-trail, stick to snow and rock when possible so as not to damage fragile alpine meadows. Spread out when traveling off-trail; if you're hiking in a group, don't hike in a line, as this greatly increases the chance of compacting thin soils and crushing delicate plant environments.

• Obey the rules specific to the trail you are visiting. Many trails are closed to certain types of use, including hiking with dogs or riding horses.

• Stay in control when hiking with dogs. Hikers who take their dogs on the trails should have their dog on a leash or under very strict voice command at all times.

Note: This Trail Etiquette rule is rendered moot in most of this book since dogs are prohibited on all trails within Mount Rainier National Park (as they are in all national parks).

• Avoid disturbing wildlife, especially in winter and in calving areas. Observe from a distance, resisting the urge to move closer to wildlife (use your telephoto lens). This not only keeps you safer, but it prevents the animal from having to exert itself unnecessarily to flee from you.

• Take only photographs. Leave all natural things, features, and historic artifacts as you found them, for others to enjoy.

• Never roll rocks off trails or cliffs. You risk endangering lives below you.

A female blue “sooty” grouse near Pinnacle Saddle

Pack It Out

Also part of trail etiquette is packing out everything you packed in, even biodegradable things such as apple cores. The phrase “leave only footprints, take only pictures” is a worthy slogan to live by when visiting the wilderness.

Practice Backcountry Bathroom Etiquette

Another important Leave No Trace principle focuses on the business of taking care of personal business. The first rule of backcountry bathroom etiquette says that if an outhouse exists, use it. This seems obvious, but all too often, folks find that backcountry toilets are dark, dank affairs and they choose to use the woods rather than the rickety wooden structure provided. It may be easier on your nose to head off into the woods, but this disperses human waste around popular areas. Privies, on the other hand, concentrate the waste and thus minimize contamination of area waters. The outhouses get even higher environmental marks if they feature removable holding tanks that can be air-lifted out. These johns and their accompanying stacks of tanks aren't exactly aesthetically pleasing, but having an ugly outhouse tucked into a corner of the woods is better than finding toilet paper (or worse) strewn about.

When privies aren't provided, the key factor to consider is location. You'll want to choose a site at least 200 to 300 feet from water, campsites, and trails. A location well out of sight of trails and viewpoints will give you privacy and reduce the odds of other hikers stumbling onto the site after you leave. Other factors to consider are ecological: surrounding vegetation and some direct sunlight will aid decomposition.

Once you pick your place, start digging. The idea is to make like a cat and bury your waste. You need to dig down through the organic duff into the mineral soil below—a hole 6 to 8 inches deep is usually adequate. When you've taken care of business, refill the hole and camouflage it with rocks and sticks—this helps prevent other humans, or animals, from digging in the same location before decomposition has done its job. And pack out your used toilet paper—don't bury it.

Cleanup

When washing your hands, first rinse off as much dust and dirt as you can in just plain water. If you still feel the need for a soapy wash, collect a pot of water from a lake or stream and move at least 100 feet away. Apply a tiny bit of biodegradable soap to your hands, dribble on a little water, and lather up. Use a bandanna or towel to wipe away most of the soap, and then rinse with the water in the pot. Be sure to discard any wash water at least 100 feet away from natural water sources.

WATER

You'll want to treat your drinking water in the backcountry. Wherever humans have gone, germs have gone with them—and humans have gone just about everywhere. That means that even the most pristine mountain stream may harbor microscopic nasties such as Giardia cysts, Cryptosporidium, or E. coli.

Treating water can be as simple as boiling it, chemically purifying it (adding tiny iodine tablets), or pumping it through one of the new-generation water filter or purifiers. (Note: Pump units labeled as filters generally remove everything but viruses, which are too small to be filtered out. Pumps labeled as purifiers use a chemical element—usually iodine—to render viruses inactive after all the other bugs are filtered out.) Never drink untreated water, or your intestines will never forgive you.

WILDLIFE

Bears

There are an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 black bears in Washington, and the big bruins can be found in every corner of the state. The central and southern Cascades are especially attractive to the solitude-seeking bears. Watching bears graze through a rich huckleberry field or seeing them flip dead logs in search of grubs can be an exciting and rewarding experience—provided, of course, that you aren't in the same berry patch.

Bears tend to prefer solitude to human company and will generally flee long before you have a chance to get too close (see “Bear in Mind”). There are times, however, when bears either don't hear hikers approaching or they are more interested in defending their food source—or their young—than they are in avoiding a confrontation. These instances are rare, and there are things you can do to minimize the odds of an encounter with an aggressive bear (see “The Bear Essentials”).

Cougars

Very few hikers ever see a cougar in the wild. Not only are these big cats some of the most solitary, shyest animals in the woods, but there are just 2500 to 3000 of them roaming the entire state of Washington. Still, cougars and hikers do sometimes encounter each other (see “This Is Cougar Country”). In these cases, hikers should, in my opinion, count their blessings—they will likely never see a more majestic animal than a wild cougar.

To make sure the encounter is a positive one, hikers must understand the cats. Cougars are shy but very curious. They will follow hikers simply to see what kind of beasts we are, but they very rarely (as in, almost never) attack adult humans. See “Cool Cats” for how to make the most of your luck.

GEAR

No hiker should venture far up a trail without being properly equipped, starting with the feet. A good pair of boots can make the difference between a wonderful hike and a horrible death march. Keep your feet happy, and you'll be happy.

BEAR IN MIND

Here are some suggestions for helping to avoid running into an aggressive bear:

• Hike in a group and only during daylight hours.

• Talk or sing as you hike. If a bear hears you coming, it will usually avoid you. When surprised, however, a bear may feel threatened. So make noises that will identify you as a human—talk, sing, rattle pebbles in a tin can—especially when hiking near a river or stream (which can mask more subtle sounds that might normally alert a bear to your presence).

• Be aware of the environment around you, and know how to identify bear sign. Overturned rocks and torn-up deadwood logs often are the result of a bear searching for grubs. Berry bushes stripped of berries—with leaves, branches, and berries littering the ground under the bushes—show where a bear has fed. Bears will often leave claw marks on trees, and since they use trees as scratching posts, fur in the rough bark of a tree is a sign that says “a bear was here!” Tracks and scat are the most common signs of a bear's recent presence.

• Stay away from abundant food sources and dead animals. Black bears are opportunistic and will scavenge food. A bear that finds a dead deer will hang around until the meat is gone, and it will defend that food against any perceived threat.

• Keep dogs leashed and under control. Many bear encounters have resulted from unleashed dogs chasing a bear: The bear gets angry and turns on the dog. The dog gets scared and runs for help (back to its owner). And the bear follows right back into the dog owner's lap.

• Leave scented items at home—perfume, hair spray, cologne, and scented soaps. Using scented sprays and body lotions makes you smell like a big, tasty treat.

• Clean fish away from camp. Never clean fish within 100 feet of camp.

But you can't talk about boots without talking about socks. There's only one rule here: wear whatever is most comfortable, unless it's cotton. The corollary to that rule is this: never wear cotton.

Cotton is a wonderful fabric when your life isn't on the line—it's soft, light, and airy. But get it wet, and it stays wet. That means blisters on your feet. Wet cotton also lacks any insulation value. In fact, get it wet, and it sucks away your body heat, leaving you susceptible to hypothermia. So leave your cotton socks, cotton underwear, and even the cotton T-shirts at home. The only cotton I carry on the trail is my trusty pink bandanna (pink because nobody else I know carries pink, so I always know which is mine).

While the list of what to pack varies from hiker to hiker, there are a few things each and every one of us should have in our packs. For instance, every hiker who ventures more than a few hundred yards away from the road should be prepared to spend the night under the stars (or under the clouds, as may be more likely)—just in case. Mountain storms can whip up in a hurry, catching sunny-day hikers by surprise. What was an easy-to-follow trail during a calm, clear day can disappear into a confusing world of fog and rain—or even snow—in a windy tempest. Therefore, every member of the party should pack the Ten Essentials, as well as a few other items that aren't necessarily essential but would be good to have on hand in an emergency. (Also see “Day Hiker's Checklist.”)

The Ten Essentials

1. Navigation (map and compass): Carry a topographic map of the area you plan to be in, and know how to read it. Likewise, carry a compass—and again, make sure you know how to use it.

2. Sun protection (sunglasses and sunscreen): In addition to sunglasses and sunscreen (SPF 15 or better), take along physical sun barriers such as a wide-brimmed hat, a long-sleeved shirt, and long pants.

3. Insulation (extra clothing): This means you should have more clothing with you than you would wear during the worst weather of the planned outing. If you get injured or lost, you won't be moving around and generating heat, so you'll need to be able to bundle up.

4. Illumination (flashlight or headlamp): If you're caught after dark, you'll need a headlamp or flashlight to be able to follow the trail. If you're forced to spend the night outdoors, you'll need it to set up an emergency camp, gather wood, and so on. Carry extra batteries and a spare bulb too.

5. First-aid supplies: Nothing elaborate is needed—especially if you're unsure how to use less familiar items. Make sure you have adhesive bandages, gauze bandages, some aspirin, and so on, and carry any personal medications you need in case you get caught out longer than expected. At minimum, a Red Cross first-aid training course is recommended. Better still, sign up for a Mountaineering Oriented First Aid course (MOFA) if you'll be spending a lot of time in the woods.

Lupine leaf munchies for a hoary marmot near the Golden Gate trail

6. Fire (firestarter and matches): An emergency campfire provides warmth, but it also has a calming effect on most people. Without one, the night can be cold, dark, and intimidating. With one, the night is held at arm's length. A candle or tube of firestarting ribbon is essential for starting a fire with wet wood. And of course matches are an important part of this essential. You can't start a fire without them. Pack them in a waterproof container and/or buy the waterproof-windproof variety. Book matches are useless in wind or wet weather, and disposable lighters can be unreliable.

7. Repair kit and tools (including a knife): A pocketknife is helpful; a multitool is better. You never know when you might need a small pair of pliers or scissors, both of which are commonly found on compact multitools. A basic repair kit includes such things as a 20-foot length of nylon cord, a small roll of duct tape, some 1-inch webbing and extra webbing buckles (to fix broken pack straps), and a small tube of superglue.

8. Nutrition (extra food): Pack enough snacks so that you'll have leftovers after an uneventful trip—those leftovers will keep you fed and fueled during an emergency.

9. Hydration (extra water): Figure what you'll drink between water sources, and then add an extra liter. If you plan on relying on wilderness water sources, be sure to include some method of purification, whether a chemical additive, such as iodine, or a filtration device.

10. Emergency shelter: This can be as simple as a few extra-large garbage bags or something more efficient, such as a reflective space blanket or tube tent.

TRAILHEAD CONCERNS

Sadly, the topic of trailhead and trail crime must be addressed. As urban areas continuously encroach upon our green spaces, societal ills follow along.

But by and large, our hiking trails are safe places—far safer than most city streets. Common sense and vigilance, however, are still in order. This is true for all hikers, but particularly so for solo hikers.

Be aware of your surroundings at all times. Leave your itinerary with someone back home. If something doesn't feel right, it probably isn't. Take action by leaving the place or situation immediately. But remember, most hikers are friendly, decent people. Some may be a little introverted, but that's no cause for worry.

COOL CATS

If you encounter a cougar, remember that these animals rely on prey that can't, or won't, fight back. So as soon as you see the cat, take the following precautions:

• Do not run! Running may trigger a cougar's attack instinct.

• Stand up and face it. Virtually every recorded cougar attack on humans has been a predator-prey attack. If you appear as another aggressive predator rather than as prey, the cougar will likely back down.

• Try to appear large. Wave your arms or a jacket over your head.

• Pick up children and small dogs. They're more likely to be attacked than a large adult, since the cougar will identify them as easier prey.

• Maintain eye contact with the animal. The cougar will interpret this as a show of dominance on your part.

• Back away slowly if you can safely do so. Don't turn your back on a cougar!

Where the road used to be: now a finger of the Carbon River flows in the old roadbed of the Carbon River Road.

By far your biggest concern should be with trailhead theft. Car break-ins are a far too common occurrence at some of our trailheads. Do not—absolutely under any circumstances—leave anything of value in your vehicle while out hiking. Take your wallet, cell phone, and listening devices with you, or better yet, don't bring them along in the first place. Don't leave anything in your car that may appear valuable. A duffle bag on the backseat may contain only dirty T-shirts, but a thief may think there's a laptop in it. If you do leave a duffle of clothes in the car, unzip it so prowlers can see that it does indeed have just clothes inside. Save yourself the hassle of returning to a busted window by not giving criminals a reason to clout your car.

If you arrive at a trailhead and someone looks suspicious, don't discount your intuition. Take notes on the person and his or her vehicle. Record the license plate and report the behavior to the authorities. Don't confront the person. Leave and go to another trail.

Although most car break-ins are crimes of opportunity, organized bands intent on stealing personal identification have also been known to target parked cars at trailheads. While some trailheads are regularly targeted and others rarely, if at all, there's no sure way of preventing this from happening to you other than being dropped off at the trailhead or taking the bus (rarely is either an option). But you can make your car less of a target by not leaving anything of value in it.

ENJOY THE TRAILS

Above all else, I hope you can safely enjoy the trails in this book. These trails exist for our enjoyment and for the enjoyment of future generations. We can use them and protect them at the same time if we are careful with our actions and forthright with our demands on Congress to continue and further the protection of our country's wildlands.

DAY HIKER'S CHECKLIST

ALWAYS CARRY THE TEN ESSENTIALS

• See the list in the Introduction.

THE BASICS

• Day pack (just big enough to carry all your gear)

CLOTHING

• Polyester or nylon shorts or pants

• Short-sleeved shirt

• Long-sleeved shirt

• Wicking long underwear

• Non-cotton underwear

• Bandanna

OUTERWEAR

• Warm pants (fleece or microfleece)

• Fleece jacket or wool sweater

• Raingear

• Wide-brimmed hat (for sun or rain)

• Fleece or stocking hat (for warmth)

• Gloves (fleece or wool and shell)

FOOTWEAR

• Hiking boots

• Hiking socks (not cotton!). Carry one extra pair. When your feet are soaked with sweat, change into the clean pair, then rinse out the dirty pair and hang them on the back of your pack to dry. Repeat as often as necessary during the hike.

• Liner socks

• Extra laces

• Gaiters

• Moleskin (for prevention of blisters) and Second Skin (for treatment of blisters). Carry both in your first-aid kit.

OPTIONAL GEAR

• Camera

• Binoculars

• Reading material

• Fishing equipment

• Field guides (for nature study)

• Head net or mosquito net suit

Kautz Creek and Mount Rainier seen as you cross the wide bed of Kautz Creek hiking toward Pyramid Creek Camp

Throughout the twentieth century, wilderness lovers helped secure protection for the lands we enjoy today. As we enter the twenty-first century, we must see to it that those protections continue and that the last bits of wildlands are also preserved for the enjoyment of future generations.

Please, if you enjoy these trails, get involved. Something as simple as writing a letter to Congress can make a big difference.

A NOTE ABOUT SAFETY

Safety is an important concern in all outdoor activities. No guidebook can alert you to every hazard or anticipate the limitations of every reader. Therefore, the descriptions of roads, trails, routes, and natural features in this book are not representations that a particular place or excursion will be safe for your party. When you follow any of the routes described in this book, you assume responsibility for your own safety. Under normal conditions, such excursions require the usual attention to traffic, road and trail conditions, weather, terrain, the capabilities of your party, and other factors. Keeping informed on current conditions and exercising common sense are the keys to a safe, enjoyable outing.

The Mountaineers Books