First, a confession: Becoming a cheesemaker was never a dream of mine.

Growing up, I had no idea that I would one day return to the farm, along with my husband of more than a quarter century and our daughters, to build a small goat dairy. Life often takes you on a journey with an unknown destination. Finding your dream is sometimes as simple as holding on and letting the current lead you to it.

My sister and I were raised with the unspoken—but almost completely enforced—motto of “If we can’t grow it, we can’t eat it.” Our family gardened, canned and froze produce, milked cows, and raised cattle for beef and chickens for eggs. We churned butter and made a Greek-style drained yogurt (my mother reports that as a child I would gorge upon this until I was almost sick). My mom tried her hand at aged cheeses too, but there just weren’t the information or supplies available back then to help the home cheesemaker learn the ropes, and also there was no one around from the previous generation to pass along the wisdom.

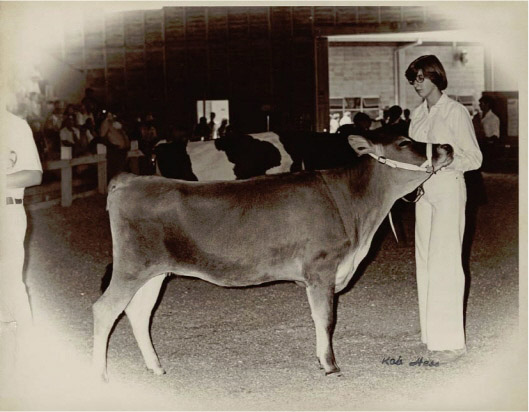

I was a cowgirl: I had my two 4-H Jersey cows, Daffodil and Butterscotch. I sold their milk as a teenager, showed them at the fair, and later became a dairy cattle 4-H leader—but still I had no thoughts of making cheese. I became a licensed practical nurse, not because I wanted to (I wanted to be an artist) but because that was where the jobs were. I tried writing fiction but found that my own talents paled in comparison to the abilities of the authors I loved to read. Eventually, in the late 1980s, I was able to pursue the fine arts of painting and printmaking and take those to what, for me personally, was the apex of expression.

During these years of nursing and printmaking, Vern and I traveled wherever his career in the Marine Corps led us. My cows traveled with me, in a sense—but now they were a herd of porcelain and china mementos given to me by friends and family who understood my love of bovines. We had a horse or two, and often a solitary goat for their companion. I look back on these goats with an apology for not appreciating at the time their uniqueness, both as a species and as individuals. But back then my heart was still with the four-teaters.

At Vern’s last duty station with the USMC, we finally owned a piece of property on which we could have a few farm animals. Chickens came first. I have always felt that having a few chickens immediately grounds one to the planet—a circle of life in miniature: you feed them, they feed you. Not to mention, chickens are a hoot!

Author at age fourteen showing her first cow, Daffodil, at the county 4-H fair, 1976.

Finally I started thinking about “something to milk.” I wanted our family to have a source of better-quality food. I wanted to not have to use store-bought, factory-farmed milk to make our yogurt. So I went cow shopping. However, the reality of their size, their impact on the land, and the volume of—how shall I say it—poop started to change the way I saw my future with the species.

A neighbor at the time gave me an article from Mother Earth News that discussed dairy goats. Now, I had tasted bad goat milk. I had smelled bucks. I didn’t think of myself as a goat person. But our youngest daughter wanted to be involved with this milking thing we were embarking on, and the idea of her, at age eight, trying to lead a big cow around was not inspiring. The article mentioned a goat breed that I had not known in my 4-H days, the Nigerian Dwarf dairy goat. They were cute, they were colorful, and best of all, they were little. Amelia was hooked, I was intrigued. The current of our life had shifted.

I started learning how to make cheese before the goats arrived. Using Ricki Carroll’s venerable book Home Cheese Making, I wowed myself and our friends by making fromage blanc and quick mozzarella. The magic of those first batches is still fresh in my memory.

And then we fell in love with the goats.

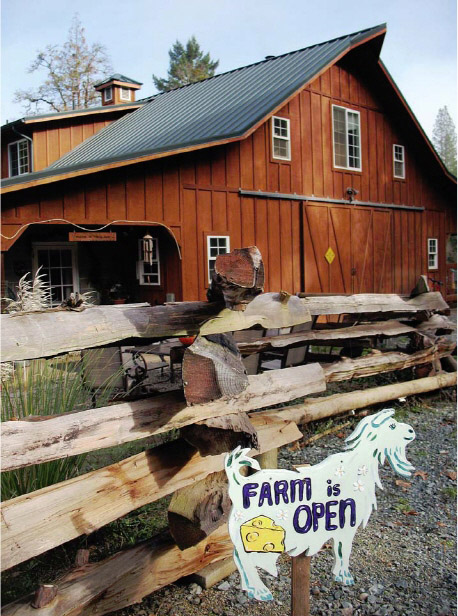

A couple of years later Vern was getting close to retiring from the Marine Corps. We knew we could move back home to rural southern Oregon and live on part of my family’s original farmland. But what kind of work could Vern find that would both be fulfilling for him and allow me to stay at home, make cheese, ride the horses, and “do art”? By this time I was making hard cheeses, teaching some beginning classes, and having a ball. Vern had always been a cheese nut and a lover of all dairy products, so he had no complaints. Amelia and our older daughter, Phoebe, didn’t seem to mind helping devour the spoils of my labor, either. Amelia and I had an idea: We could move back to Oregon and start a little cheese dairy. Vern was all for it.

Barn at Pholia Farm.

We were swept up by the intensity of the venture and have been holding on ever since—sometimes thrilled, sometimes wanting to jump ship, but for the most part amazed and fulfilled.

In the process of writing this book I have satisfied some of my own cravings, for knowledge and for expressing myself through writing. Some questions that we still had about the business after all these years have been answered, and other new ones have been raised. I hope the wisdom and knowledge shared with me for this book by cheesemakers from across the country will help those whose journey to cheesemaking is just beginning, and even those of us who are still on board and enjoying the ride.

Bon voyage!

“I may not have gone where I intended to go,

but I think I have ended up where I intended to be.”

—Douglas Adams, 1952–2001