15 | Heredity and the Jew

Redcliffe N. Salaman

“Heredity and the Jew,” Journal of Genetics 1, no. 3 (1911): 273–92.

Redcliffe Salaman (1874–1955) was an English pathologist and geneticist, and an activist on behalf of the Anglo-Jewish community and Zionism. He is best known for his research into the history and influence of the potato. He also published a number of works related to Jews and race, Jews and medicine, and Palestine. See Todd Endelman, “Anglo-Jewish Scientists and the Science of Race,” Jewish Social Studies 11, no. 1 (2004): 52–92.

[. . .]

Ethnologists may be said to agree that the Jew is not racially pure, but on the other hand they have to admit that the Jews constitute a definite people in something more than a political sense, and that they possess though not a uniform, still a distinguishing, type.

Nothing is more confusing than the varied accounts of the shapes of head, nose, eyes, and color of the hair of Jews in different countries, and if one’s only acquaintance with Jews were through the literature of anthropology one would be inclined to think that the “chosen people” had no existence apart from books, and the imagination of the anti-Semites. It is with no small degree of comfort therefore, that one finds Ripley66 making the following statement: “Who has not, on the other hand, acquired a distinct concept of a Jewish face and of a distinctly Jewish type? Could such a patent fact escape observation for a minute?” Again, Weissenberg67 says: “The Jew in an anthropological sense forms no specific type, but the facial expression is absolutely characteristic.” Fischberg [sic] is not so wholehearted as to [wholeheartedly convinced of] the general occurrence of this characteristic facial expression but he does recognize it and considers it not strictly a physical trait but rather an expression of the soul. Others will tell us that this Jewish expression, so impossible to define, is merely an emblem of the ceaseless wanderings and the countless agonies of the Jew—of the tausend-jährigen Schmerz, as Heine calls it. Others again tell us it exists because the Jew is landless, and if only he were once more back in his native land, the facial type would vanish. All, however, practically agree that whether blond or dark, tall or short, long-headed or round-headed, the Jew is a Jew because he looks like one. The peculiar facial expression is at least not the outcome of recent times. We have evidence of the greatest antiquity. In the Assyrian sculptures, 800 [BCE], are depicted Jewish prisoners who are thoroughly Jewish, and Petrie68 has brought home from Memphis terra-cotta heads dating [from] 500 [BCE] of Jews at once recognizable by their Jewishness. On a forest roll of the pre-expulsion times in England is a pen-and-ink sketch, or one might rather say a caricature of a certain Aaron, “Son of the Devil,” dated 1277, which, crude though it is, hits off [depicts] a distinctly Jewish type. The great master Rembrandt has given us numerous drawings of Jews. He was mainly attracted by the Sephardic Jews, but whatever the shape of their face may be, the curious expression that we recognize as Jewish never escaped the artist. More interesting than the examples given of the persistence of this facial expression is the fact that the Samaritans of today who live in the land of their forefathers, have an unmistakable Jewish expression, and this though their heads are dolichocephalic and those of the majority of Jews brachycephalic.

At this point one might with advantage consider the relation that the existence of the Kohanim has to the question of Jewish type. The Kohanim are the traditional descendants of the tribe of Aaron. There is, of course, no written record of such descent, but the hallmark, as a rule, is shown by the name of Cohen or some modification of it. It is not at all unusual, however, to find people not possessed of the name of Cohen who are still Kohanim. It is most improbable that anyone could, and much less would, assume the title of Kohen without having a right by birth because it conveys neither social distinction nor advantage, while on the other hand, it brings in its train some undoubted disabilities, the chief of which directly concerns us, and is that no Kohen, according to Jewish law, can marry a stranger, a proselyte or the daughter of a proselyte, or a divorcée: so that we have a sect whose descent may be regarded as strictly Jewish. If now we review the physiognomies of the various Kohanim, it will be found that they exhibit no type in any way distinct from that of other Jews. Every phase of Jewish bodily form will find its representative among the Kohanim, so that one is inclined very much to the view that whatever value may be ascribed—and I personally think a very high one may be—to the purity of descent of the Kohanim during the last 2,000 years, practically the same value may be ascribed to their brethren among whom they live.

What the elements are that go to make up the expression of a face that is at once so elusive of description and yet so characteristic, it is difficult to say. The nose is often peculiar, not because of its length or even its convexity, which may be often outdone in non-Jews, but by the heavy development of the nostrils. Jacobs has described this “nostrility” and has most aptly compared the Jewish nose to the figure six with a long tail. Remove the tail, he says, and the Jewishness will disappear. The eyes are generally elongated, and a fairly characteristic feature is the length of the upper eyelid. The face that exhibits the expression of Jewishness is never of the angular type with square jaw, a type that is indeed extremely rare among Jews. Far more usual is it to find rounded features, long sloping jaw, fairly developed chin that is round and not square, a good-size forehead devoid of that angularity in the region of the temples that is not uncommon among Teutonic people. However it may be brought about, there is no doubt that the character of Jewishness is a real one. Weissenberg69 relates that he put several hundred photographs of Russians and Russian Jews without peculiar dress or other distinguishing feature before two scientific friends, one a Jew, the other a native Russian. His Jewish friend picked out 70 percent of the Jewish subjects correctly and the Russian 50 percent. If so high a percentage of Jews could be identified by their looks alone in a photograph, it is not surprising that the opinion is current that the Jew may be recognized wherever he goes. Notwithstanding the fact that the great majority of Jews look Jewish, it cannot be denied that one meets, not rarely, individuals, perhaps more often men than women, who do not exhibit this type and who are either indistinguishable or at least practically indistinguishable from North Europeans. It is relying on these apparently non-Jewish faces that Fischberg [sic] and others have rashly assumed that they are the direct results of mixture with the surrounding people. I think I shall be able to offer some evidence that will show that this view is untenable.

Impressed with the great frequency and the distinctiveness of the Jewish type of face, it occurred to me that this character might form excellent material for research on Mendelian lines. Intermarriage today with the English is very common in Anglo-Jewry, and one had only to follow out such cases of mixed marriage to obtain results comparable to those the genetic student has been obtaining in plants and animals. My method has been to collect personally, as far as possible, all cases of mixed marriage and to obtain the assistance of those on whom I could rely, and whose duty it was merely to state whether they considered the children of the mixed marriages of their acquaintance as Jewish or gentile in appearance. Most of my observers were quite ignorant of the purpose of my examination and of the results I expected, while none were conversant with Mendelian or other theories of heredity. All who have assisted me have been themselves Jews, and I have noted a distinct tendency on their part to claim, wherever possible, a Jewish type of face for the children they have examined, and although, as I shall show, the results are entirely in the opposite direction, yet what error there is, is distinctly toward increasing the number of supposed Jewish faces in the offspring of mixed marriage. Wherever possible, I have seen the children myself or have obtained photographs, but in at least half of them, I have had to rely on others. In doing so I have been rather encouraged than otherwise by finding that the bias of my assistants has been always against the results that they, to their own surprise, have found. In all cases the Jew is of the Ashkenazi section and the gentile is either a native of England or Northern Europe.

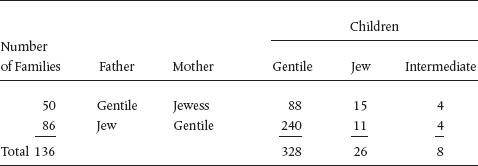

TABLE 15.1

FIRST GENERATION

Briefly, the results of the intermarriage of Jew and Gentile may be stated thus [see table 15.1].

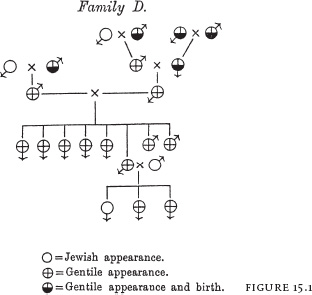

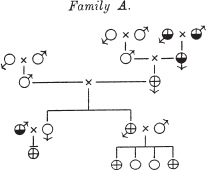

In fifty families where the father was gentile and the mother a Jewess, there were 88 Gentile-looking children, 15 Jewish, and 4 intermediate in type. In eighty-six families where the father was Jewish and the mother gentile, there were 240 Gentile-looking children, 11 Jewish, and 4 intermediate. In both cases the intermediates are practically gentile-looking. Adding the two classes together, we find that there are 336 gentile children to 26 Jewish—that is 13 gentile to 1 Jewish. The result is a surprise to both the anthropologist and to the Mendelian. To the former who looks for blending, we have the fact that, so far from blending, we have no less than 93 percent of the mixed bred offspring resembling one parent only. To the Mendelian some surprise must occur [at the fact] that the dominance is not absolute, but this is, to a slight extent, due to the Jewish bias in the observations and, to a much greater extent, to a Jewish permeation of the English people in certain localized districts that is much more prevalent than is generally suspected. I have, while making these observations, come across certain cases where I was assured that in a certain family the father was a Jew, the mother a gentile. In one such [family], I examined the children carefully and found that two were without doubt gentile in appearance while one was equally without doubt Jewish. I then discussed the family history with the parents, and I was able to obtain the pedigree shown in Figure 1, which at once explains the occurrence of the Jewish child. In another case I found a very similar state of affairs, but I was unable to trace it further as the non-Jewish parent objected [declined] to elucidate the Jewish blood in her grandparent, which she, however, admitted. In a third and fourth case where complete dominance was expected but not obtained, I have reason to believe that it will be discovered that the gentile parent has Jewish ancestors. In determining the nature of so complex a character as the facial expression, the personal equation of the observer must play an important part. I have in some cases found that observers not specially acquainted with the subject, although agreeing that a given individual of the first generation is of gentile appearance, have yet felt that there was somewhere lurking in the face an expression that suggested “Jewishness,” and there is very little doubt that such opinion may often be well founded. I have myself come across a few cases where without doubt the recessive Jewish facial expression has come to the surface as the individual grew older. One case was particularly apparent. The parents were characteristically Jewish and non-Jewish respectively; there was a large family, of which I saw one personally and the remainder in photographs. Most of them were, to my mind, not Jewish at all, but the one whom I was interviewing, though not in any way strikingly Jewish, would probably have been recognized by many people as such. His age was about forty-five, and he assured me, and his assurance was confirmed by his wife, that when he was a young man he was never by any chance recognized as a Jew in public. This same individual has married a gentile and has three children who are, I think, without doubt totally non-Jewish in appearance. It is not without surprise that one finds that very many of the leading families of this country, as given in Burke [Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage], contain Jewish blood, and I know of at least one case where two parents, neither Jewish in appearance, have a daughter who is typically Jewish. A reference to Burke showed that in the family tree of both parents was Jewish blood.

FIGURE 15.1

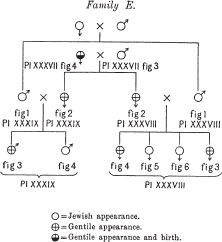

To obtain portraits of families for the purpose of exhibition has been a most difficult matter, but I am able to show in Plates XXXVIII and XXXIX a few examples [the plates are not included in this book].

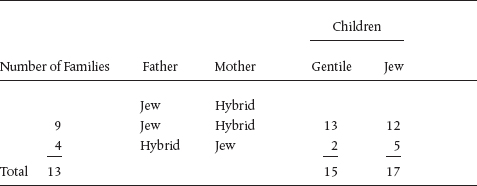

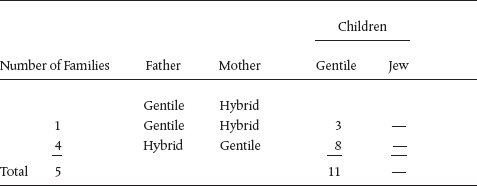

To the student of heredity, the phenomenon of dominance is, after all, a matter of secondary importance. The vital question that he has to deal with is, whether the character in question is one that segregates or not—that is, when in an individual the character and its opposite are both present, are these two opposite characters represented together in the sex cells or gametes, or does one go to one gamete and the other to another? Two methods are open to us in testing this question, one to observe the matings of the hybrid individual with those possessing recessive character only, the other to observe the matings of such hybrid individuals with each other. Of the matings of hybrid with hybrid I have not found a single example. This is hardly surprising when one considers the vastly greater choice the hybrid has of finding his mate either in the Jewish community or in the outside world. Of matings between hybrid and Jew I have nine families where the Jew is the father and the hybrid the mother, giving rise to twenty-five children, thirteen of whom are undoubtedly gentile and twelve are unequivocally Jewish. Four families where the father is hybrid and the mother Jewish contain seven children, of which two are gentile and five are Jewish. Taking the families together, their offspring consist of fifteen gentile and seventeen Jewish children, the Mendelian expectation being equality. Besides these matings, I have been able to collect a certain number of families where a hybrid has married a gentile. In four the father is hybrid, the mother gentile, with eight offspring, all gentile in appearance. In one the mother is hybrid and father gentile, with three gentile offspring (cf. Table[15.3]). I have indirect knowledge of several other families comprising a large number of children, all of whom are said to be gentile in appearance, but I have not included them as the observations were not sufficiently reliable.

TABLE 15.2

HYBRID AND JEW

TABLE 15.3

SECOND GENERATION

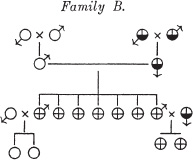

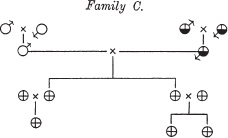

In Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5 are given further pedigrees showing the results of the matings of hybrid individuals with Jews and gentiles, respectively.

FIGURE 15.2

FIGURE 15.3

FIGURE 15.4

FIGURE 15.5

The conclusion to which these results inevitably lead is that the Jewish facial type, whether it be considered to rest on a gross anatomical basis or whether it be regarded as the reflection in which facial musculature of a peculiar psychical state, is a character that is subject to the Mendelian law of heredity.

Notes

66. William Z. Ripley. The Races of Europe. New York, 1889, p. 383.

67. Census Bulletin. No. 19, 1890, p. 10.

68. [Flinders Petrie, “Palace of Apries Memphis, vol. II, plate XXVIII, British School of Archaeology, in Egypt, 1909, p. 155.]

69. Census Bulletin. No. 19, p. 12.