A German soldier stands guard at an Atlantic Wall artillery bunker during World War II. (Topfoto)

The Atlantic Wall was the largest fortification effort in recent European history, rivalled only by France’s Maginot Line. The portions in France consumed over 17,000,000m3 of concrete and 1,200,000 tonnes of steel and cost some 3.7 billion Reichmarks. To put this in some perspective, the steel consumption was about 5 per cent of German annual production and roughly equivalent to the amount used in annual German tank production.

If the Atlantic Wall had been carefully designed and skilfully integrated into Germany’s strategic planning, it might have been worth its considerable cost. But it was created on Hitler’s whim, built in haste with little coordinated planning, and fitted uncomfortably with the Wehrmacht’s tactical doctrine. Hitler ordered its construction in response to British raiding along the English Channel and as a barrier to an anticipated Allied invasion. Wehrmacht commanders had little influence on this scheme, and a debate raged until D-Day over the best way to resist the inevitable Allied amphibious assault. The overstretched German war economy was unable to match Hitler’s dream of ‘Fortress Europe’, and the Atlantic Wall was never fully completed. The Wehrmacht commander in France, Rundstedt, later derided the Atlantic Wall as an enormous propaganda bluff.

On D-Day, the Atlantic Wall was strongest where the German leadership expected the Allied invasion, the ‘Iron Coast’ of the Pas-de-Calais opposite Britain. The Allies wisely chose to avoid this heavily defended area and struck instead where the Atlantic Wall was weaker in lower Normandy. The D-Day assault overcame the Atlantic Wall in less than a day. Other stretches of the Atlantic Wall, especially near the Channel ports, were involved in later fighting but proved no more effective.

The army preferred heavy railway guns over massive fixed guns for long-range firepower. This is a Krupp 203mm K(E) of battery EB.685 stationed near Auderville-Laye in the Cherbourg sector shortly after its capture in June 1944. (NARA)

Coastal defence had been assigned to the Kriegsmarine since the reforms of Kaiser Wilhelm in the late 1880s. This mission focused on the defence of Germany’s ports along the North Sea and Baltic coasts. By the time of World War I, German naval doctrine saw coastal defence as a series of layers beginning with warships and submarines at sea as the initial barrier, followed by coastal forces such as torpedo boats and small submarines as the inner layer, and eventually fixed defences such as minefields and shore batteries as the final defensive layer. Fortification played a minor role. During World War I, this doctrine was found inadequate when Germany occupied Belgium. The Kriegsmarine did not have the manpower nor resources to create an adequate defence along the coast of Flanders, and the dominance of the Royal Navy in the English Channel undermined the traditional tactics, since German warships stood little chance of challenging the British on a day-to-day basis. The Kriegsmarine was obliged to turn to the Army to assist in this mission, particularly in the creation of gun batteries along the coast to discourage British raiding or possible amphibious attack. These gun batteries were employed in elementary Kesselbettungen (kettle positions), so named for the pan-like shape of the fortification. The Kriegsmarine began to pay more attention to the need for fortification in the late 1930s after Germany’s re-militarization under Hitler’s new Nazi government. One of the first major coastal fortification efforts took place on the islands in the Helgoland Bay, along the North Sea coast.

At the start of World War II, the Kriegsmarine retained the traditional coastal defence mission. There was no dedicated coastal defence force, but rather the mission was simply one of those assigned to the regional naval commands. The North Sea coast was defended with a scattering of coastal batteries and newly installed naval Flak units, but there was little modern fortification construction prior to 1939. Following the defeat of France in the summer of 1940, the Wehrmacht began preparations for an amphibious assault on Britain, Operation Seelöwe (Sealion). On 16 July 1940, Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16, which called for the creation of fortified coastal batteries on the Pas-de-Calais to command the Straits of Dover and to protect the forward staging areas of the German invasion fleet.

Since it would take time to erect major gun batteries, the first heavy artillery in place was Army railroad guns that began arriving in August 1940. To provide these with a measure of protection against British air attack, several cathedral bunkers (Dombunker) were created near the coast at Calais, Vallée Heureuse, Marquise and Wimereux. At the time, the Army had nine railroad artillery regiments with a total of 16 batteries and the Kriegsmarine had a pair of 15cm railroad guns known as Batterie Gneisenau. The Army created a coastal artillery command to manage this new mission and the Army artillery along the English Channel was put under the command of Army Artillery Command 104. There was some dispute between the Army and Kriegsmarine over the direction of the coastal artillery, with an eventual compromise being reached that the Kriegsmarine would direct fire against naval targets while the Army would direct fire against land targets and take over control once the invasion of Britain began.

The Atlantic Wall.

Following the arrival of the railroad guns, both the Army and Kriegsmarine began to move other types of heavy artillery to the Pas-de-Calais. The Kriegsmarine obtained some of these by stripping existing coastal fortifications, while the Army obtained some weapons from the West Wall border fortifications or from field army heavy artillery regiments. Four powerful batteries were constructed, starting in 1941, which actually had the range to reach Britain near Dover and Folkestone. These included the Lindemann, Todt, Friedrich August and Grosser Kurfürst batteries. The artillery concentration in the Pas-de-Calais pre-dated the Atlantic Wall and was in reality an offensive deployment intended to support the invasion, and not a defensive fortified position. Even though not a true part of the Atlantic Wall, these batteries would come to symbolize Fortress Europe due to their frequent appearance in propaganda films.

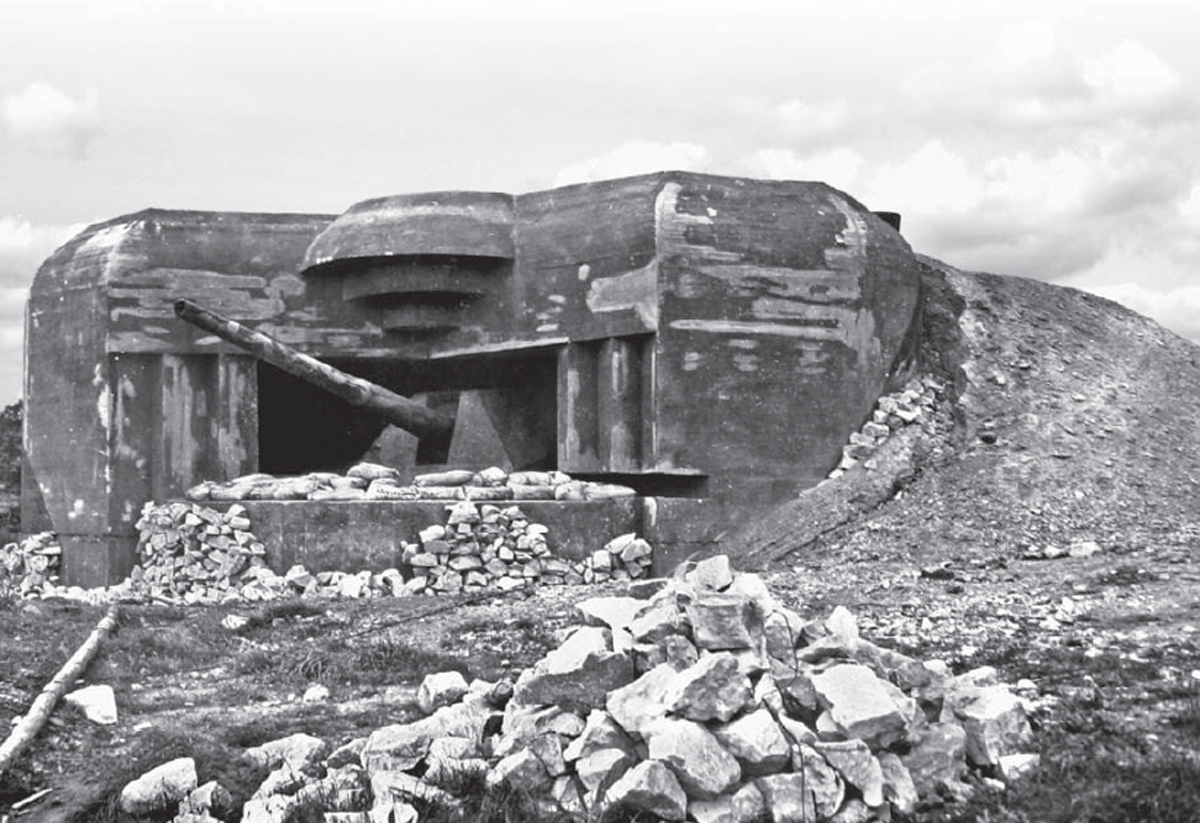

A good example of a kettle gun emplacement typical of the initial construction in 1940–42, still part of the Cherbourg defences in June 1944. The gun is a Saint-Chamond 155mm K220(f), a French World War I type widely used in the Atlantic Wall defences. Most but not all of the kettle emplacements were rebuilt with full casemates by 1944. (NARA)

The role of the Pas-de-Calais artillery batteries gradually evolved due to changing German war plans. As the possibilities for Operation Seelöwe dimmed in the winter of 1940, the role of the batteries gradually shifted to the naval interdiction role, challenging British shipping in the Channel. The railroad guns were gradually removed, especially once Hitler shifted his attention to Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia scheduled for the summer of 1941. Construction of some of the large gun batteries initiated in the summer of 1940 continued, but without any particular priority and most of the larger Pas-de-Calais batteries were not completed until well into 1942. The only area to receive special attention was the Channel Islands, which attracted Hitler’s personal interest. He wanted the islands to be heavily defended to prevent their recapture by Britain and, in October 1941, authorized the heavy fortification of the islands as a key element to this process.

MKB Graf Spee of 5./MAA. 262 in Lochrist near Brest was armed with the Krupp 28cm SKL/40 M06 originally built for the old Brauschweig class of warships and previously located on one of the Friesian islands off the northern German coast before being transferred to Brittany in 1940. Three of the four guns were in open pits like this one, and only one in a large casemate. (NARA)

Coastal defence began to attract the attention of the Wehrmacht’s occupation forces in France due to Britain’s initiation of commando raids along the Norwegian and French coasts. In February 1941, the Army began proposing a policy directive which argued that a unified defence of the coast be established, with the Army rather than the Kriegsmarine taking the lead role. This attempt was rebuffed by the OKW, which left the Kriegsmarine in charge of coastal defence artillery and the Luftwaffe in charge of Flak protection of the coast, including naval Flak batteries. Until the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, there was a general policy against extensive fortification of the French coast for fear that it would confirm that the Wehrmacht’s intention had shifted from the invasion of Britain to the invasion of Russia.

The heights of Mont de Coupole, located to the south-east of Wissant, provided an ideal observation point between Cap Gris-Nez and Cap Blanc-Nez for the heavy artillery batteries nearby. As a result, the hilltop is dotted with observation bunkers like this one. (Steven J. Zaloga)

28cm K5E railway gun Dombunker. Among the first type of fortifications built along the French coast was the Dombunker (cathedral bunker), so-called because of its resemblance to the arched shape of Gothic cathedrals. These were intended to protect three batteries of 28cm K5E railroad guns deployed to the Pas-de-Calais in the summer of 1940 and construction began in September 1940. (Lee Ray © Osprey Publishing)

British commandos staged attacks against the Lofoten Islands off the northern Norwegian coast in March and December 1941. These prompted another Führer Directive on 14 December 1941, which ordered the construction of a ‘new West Wall’. This order recognized that the Western Front was seriously short of troops due to the war in Russia, and it was proposed to substitute fortification for manpower. Light fortifications were authorized along endangered coastlines and permanent strongpoints at key points. Priority was given to the Norwegian coast, which Hitler felt was more vulnerable to such raids. Second priority went to the French coast, followed by the Dutch coast and Helgoland Bay in that order. Hitler also ordered the reinforcement of the coast defence with Flak batteries that were assigned the dual role of anti-aircraft defence and potential use against landing craft. As a consequence of this order, the OB West, Generalfeldmarschall Erwin von Witzleben, began to designate some of the key French ports as Festungsbereichen (fortified areas) to assign priorities for the eventual fortification effort. The Kriegsmarine was primarily responsible for the defence of the port itself, but the Army was assigned the task of ensuring landward defence against possible airborne attacks.

British commando raids continued in early 1942, including the daring raid on Bruneval to secure a Würzburg radar. With the Wehrmacht bogged down in Russia, it seemed likely that the Western Front would remain on a defensive footing for some time to come. The evolving strategic situation led Hitler to issue Führer Directive No. 40 on 23 March 1942, which laid the groundwork for the Atlantic Wall. The directive provided few specifics about the actual nature of the fortification, and it reaffirmed earlier priorities, with Norway and the Channel Islands being singled out for special attention. The ink was hardly dry on the new directive when it was followed a few days later by the dramatic raid on St Nazaire by British Commandos, which managed to severely damage the vital dry docks there. This led Hitler to refocus the attention of the earlier directive, with a new emphasis on the defence of ports to prevent a repeat of the St Nazaire raid. The first serious planning meeting for the Atlantic Wall occurred in May 1942 at Wehrwolf, the Führer Headquarters at Vinnitsa, and attending the meeting was the new Reichsminister for Armaments, Albert Speer, who had taken over the OT following the death of Fritz Todt in an airplane crash in February. The OT was responsible for nearly all of the major fortification and military construction programmes in France and the neighbouring countries, including the gun batteries on the Pas-de-Calais, the new U-boat bunkers on France’s Atlantic coast and the fortifications on the Channel Islands. The Wehrmacht’s Festungs-Pionier Korps (Fortress Engineer Corps) under the Inspector of Engineers and Fortifications was responsible for designing and supervising the construction of fortifications by OT.

Serious construction efforts on the Atlantic Wall began in June 1942, and this was the first time that concrete consumption for the new fortifications exceeded that for the U-boat pens. In 1943–44, OB West designated several port areas as Festungen, including Dunkirk, Calais, Boulogne, Le Havre, Cherbourg, St Malo, Brest, Lorient, St Nazaire, the Gironde estuary and the Channel Islands. The US invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 prompted the German forces to occupy Vichy France, adding another coastal region to the list. The Mediterranean coastal fortifications were dubbed the Südwall (South Wall) and are outside the scope of this book. In the event, the Mediterranean ports of Marseilles and Toulon retained the lesser and earlier designation as ‘fortified areas’, as did some Atlantic ports such as La Rochelle and Bayonne. The Festung ports were to be fortified on both the seaward and landward sides and were to be provisioned to be able to hold out for at least three months.

Batterie Lindemann, Pas-de-Calais. The casemate consumed some 17,000m3 of concrete and the gun was mounted in a fully armoured Schiessgerüst C/39 turret, directed by a massive fire-control bunker based on the S100 type, which included a large Lange optical rangefinder and was supported by a Würzburg See-Reise FuMO 214 surface-search radar located nearby on Cap Blanc-Nez, as well as several other observation and range-finding posts. (Lee Ray © Osprey Publishing)

From a coastal fortification standpoint, the most significant defences were provided by coastal artillery units. There were three principal types, the Marine-Artillerie-Abteilung (MAA), the leichte Marine-Artillerie-Abteilung (leMAA: light naval artillery battalion) and the Marine-Flak-Brigade (MaFl-Br). Each naval artillery regiment consisted of several gun batteries, each battery deployed at a single coastal artillery post with several guns, a fire-control bunker and associated defensive and support positions. There were 14 regiments along the Atlantic Wall in France plus two more (MAA. 604 and 605) on the Channel Islands. The light naval artillery battalions were peculiar to the Atlantic coast islands and were hybrid formations consisting of a few gun batteries and a few companies of naval infantry for island defence. The Navy Flak brigades, as their name implies, controlled major port anti-aircraft sites. There were three of these: III. MaFl-Br at Brest; IV. MaFl-Br at Lorient; and V. MaFl-Br at St Nazaire.

Among the massive coastal artillery casemates on the Pas-de-Calais was Turm West of MKB Oldenburg MAA. 244, armed with a 240mm SK L/50, originally a Tsarist 254mm gun captured in 1915 and re-chambered by Krupp. The two casemates of this battery were specialized SK designs built to the heavy Standard A with 3m-thick walls and ceilings. In the foreground is one of the associated H621 personnel shelters. (Steven J. Zaloga)

One style of camouflage for the shoreline casemates was trompe l’oeil painting, intended to make the bunker look like a harmless civilian home. This example is certainly more elaborate than most, complete with a cart in the false garage. This Canadian soldier is looking into the gun embrasure of the casemate, which had been covered with a false wooden cover now on the ground. (NAC PA-131229 Ken Bell)

One approach to coastal defence rarely used on the Atlantic Wall in France was the shore-based torpedo battery. The Kriegsmarine was made painfully aware of the capabilities of such batteries with the loss of warships in the 1940 Norwegian campaign, and developed a shore-based version of the standard TR 53.3 Einzel launcher from the S.Boote torpedo boat, which fired the 533mm G7a torpedo. However, these weapons were expensive and not as well suited to the open coastline of France as the constricted fjords of Scandinavia. The only significant use of shore-based torpedo stations in France was around the harbour of Brest where batteries were installed in 1942 near Crozon Island at Fort Robert and Cornouaille Point.

Batterie Todt. Construction of Batterie Siegfried began in August 1940, armed with four 38cm SKC/34 in B-Gerüst C/39 turrets, near the village of Haringzelles. The battery was located close to the sea and within sight of Cap Gris-Nez where several supporting observation posts were located. The four turrets were of a special design consisting of a main circular gun casemate with a smaller multi-storey bunker for ammunition and support located to the left of the gun pit. (Hugh Johnson © Osprey Publishing)

Until 1943, the areas between the ports were much less heavily defended than the ports. The naval coastal artillery batteries tended to be clustered around the key ports, leaving significant expanses of coastline without any protection. These were gradually covered by Army coastal artillery batteries deployed along the coast like ‘a string of pearls’ to provide a basic defensive barrier. Coastal artillery was viewed as an excellent expedient since a single battery could cover about 10km of coastline to either side of the battery. In addition, the resources needed were fairly modest since most of the batteries were created using captured French, Russian or other weapons. As in the case of other defences, the Army’s coastal batteries were most heavily deployed along the Pas-de-Calais and Upper Normandy in the 15. Armee sector, with an average density of one battery every 28km, while in the 7. Armee sector from Lower Normandy around the Cotentin Peninsula, the density was only one battery every 87km. The 15. Armee had nearly double the density of artillery of the other two sectors, averaging nearly one gun per kilometre. This certainly did not live up to the propaganda image of the Atlantic Wall. German tactical doctrine recommended a divisional frontage of 6 to 10km, implying a density of about five to eight guns per kilometre, substantially more than average Atlantic Wall densities.

Although the coastal artillery batteries were an economical way to cover large areas of coastline with minimal coverage, they could do little against commando raids. The task of patrolling the coastline was assigned to the infantry divisions stationed near the coast. These sectors consisted of divisional Küstenverteidigungs-Abschnitte (KVA; coast defence sectors), further broken down into regimental Küstenverteidigungs-Gruppen (KVG), battalion-strength Stützpunktgruppen (strongpoint groups), company-sized Stützpunkte (StP; strongpoints) and finally platoon-sized Widerstandsnester (WN; resistance points). Since the Kriegsmarine received the bulk of the construction work in 1943, these positions were often little more than field entrenchments with a small number of fortified gun pits and personnel shelters. Except on the Pas-de-Calais, there was little fortification of the infantry coastal defences until 1944. The bunkers and defensive positions were intended to compensate for the severe shortage of troops. German tactical doctrine recommended that an infantry division be allotted no more than 6–10km of front to defend, but the occupation divisions in France were frequently allotted 50 to 100km of coastline, sometimes even more in the remoter locations of Brittany or the Atlantic coast.

The allotment of fortifications was by no means uniform along the coast. In 1943, the Wehrmacht was deployed in three major formations: the 15. Armee from Antwerp westwards along the Channel coast to the Seine estuary near Le Havre; the 7. Armee from Lower Normandy to Brittany; and the 1. Armee on the Atlantic coast from the Loire estuary near Nantes to the Spanish coast near Bayonne. Of the three main sectors in France, the 15. Armee on the Channel coast received a disproportionate share of the fortification, and the 7. Armee much of the remainder. Of the 15,000 bunkers envisioned under the 1942 plan, 11,000 were allocated to the 15. and 7. Armeen and the rest to the Atlantic coast of France, the Netherlands, Norway and Denmark. By way of comparison, the 1. Armee sector, which covered the extensive Atlantic coast facing the Bay of Biscay, was allotted only 1,500 to 2,000 bunkers.

The initial role of coastal artillery was to stop the invasion force before it reached the shoreline. The configuration of the coastal artillery batteries was a subject of some controversy between the Army and Kriegsmarine. The Navy had traditionally viewed shore batteries as being an extension of the fleet, and so deployed the batteries along the edge of the coast where they could most easily to take part in naval engagements. As had become evident from attempts to repulse the Allied amphibious landings in the Mediterranean Theatre, one of the Allies’ main advantages was heavy naval gunfire. As a result, a growing focus of the Navy’s Atlantic Wall programme was to deploy enough coastal artillery to force the Allied warships away from the coast and thereby undercut this advantage. Naval coastal batteries were patterned on warship organization. The four to six guns were deployed with a direct line of sight to the sea, and connected by cabling to an elaborate fire-control bunker, which possessed optical rangefinders and plotting systems similar to those on warships to permit engagements against moving targets. The Army derided these batteries as ‘battleships of the dunes’ and argued that their placement so close to the shore made them immediately visible to enemy warships, and therefore vulnerable to naval gunfire. In addition, the proximity to the shore also made the batteries especially vulnerable to raiding parties or to infantry attack in the event of an amphibious assault.

The Army’s attitude to the coastal batteries was based on the premise that they were needed primarily to repulse an amphibious attack, not engage in naval gun duels. As a result, the Army was content to place the batteries further back from the shore, though some were located along the shore if it gave them particularly useful arcs of fire. For example, this was the case with shorelines edged with cliffs, since a coastal battery deployed on a promontory could rake the neighbouring beaches with fire, avoiding the cover of the cliffs. The Army fire-control bunkers were far less elaborate than the naval bunkers, possessing rangefinders and sighting devices but usually lacking plotting devices for engaging moving targets. The Army placed more emphasis on wire or radio connections with other Army units, depending on artillery forward observers to assist in fire direction against targets that were beyond line of sight. The Kriegsmarine complained that these batteries were incapable of engaging moving ships.

Besides their differences about coastal artillery tactics, the Kriegsmarine and Army had very different views on the ideal technical characteristics of the coastal guns. The Kriegsmarine preferred a turreted gun that could survive in a prolonged gun duel with a warship. A few actual warship turrets were available and were emplaced in areas that had a rock-bed deep enough to accommodate the sub-structure of the turret: a turret from the Gneisenau near Paimpol in Brittany, two turrets from the cruiser Seydlitz on Ré Island and the 38cm gun turret from the French battleship Jean-Bart near Le Havre. Since armour plate was at a premium and fortification too low on the Reich’s priority list, it was impossible to manufacture steel turrets for coastal artillery. This led to the development of casemates to protect the gun against most overhead fire, with a limited armoured shield around the gun itself. Such configurations limited the traverse of the gun compared to a turret. This would later prove to be a fatal flaw when the attack came from the landward side since the embrasure seldom permitted more than 120 degrees of traverse, limiting the gun’s coverage to seaward targets. The Kriegsmarine was aware of this problem but since its primary mission was to deal with the seaborne threat, the issue was brushed aside.

During 1943, fortification engineers began to experiment with an advanced type of reinforced concrete using wire under stress instead of the usual steel reinforcing bars. This promised to be significantly lighter, leading to plans for a fully traversable concrete turret to get around the limitations of traverse in fixed casemates. An experimental example was completed outside Paris in early 1944, and the first concrete turrets began to be built on the Atlantic Wall, starting with one near Fort Vert to the east of Calais. However, the technology appeared too late in the war to be widely used.

The Army did not favour fixed guns like the Navy and preferred to use conventional field artillery. This was based on the premise that the batteries could be moved from idle sectors to reinforce the defences in sectors under attack. The Army pointed to previous examples of British amphibious attack, such as Gallipoli, where the amphibious assault became a protracted campaign. At first, the Army preferred to use simple kettle mounts patterned on the World War I style, which were simply circular concrete pits with protected spaces for ammunition. The gun itself was completely exposed, but the gun pit was supported by fully protected crew bunkers, ammunition bunkers and a fire-control bunker. This was the predominant type of Army coastal battery configuration on the Atlantic Wall from 1942 into early 1943. However, as Allied air activity over the French coast increased in intensity, the vulnerability of these batteries to air attack became the subject of some concern. Intuitively it seemed that the Navy’s casemates offered better protection from air attack than the kettle positions. However, based on actual combat experiences, some of the fortification engineers argued that this was not the case. The confined casemate tended to concentrate the blast of any bomb that landed near the gun opening, and it was found that guns in open pits were almost invulnerable to air attack except for the very rare direct hit on the gun itself. In the wake of the Dieppe raid, however, the policy shifted to full protection of the Army coastal batteries in casemates. These resembled the Navy casemates except that they generally had a large garage door at the rear to permit easy removal of the gun for transfer to other sectors if needed.

The Army fortification engineers had established protection standards during the West Wall programme based on steel-reinforced concrete (Beton-Stahl). Category E fortifications were based on walls and ceilings 5m thick, but this standard was uncommon and used mainly for strategic command posts such as the Führer bunkers. The highest level for tactical fortifications was A, which used a 3.5m basis, and this was confined to large, high-priority structures such as the U-boat bunkers and some key facilities such as the heavy gun batteries on the Pas-de-Calais and special military hospitals. Most Atlantic Wall fortifications were built to the B standard, which was 2m thick, proof against artillery up to 210mm and 500kg bombs. Many minor bunkers, such as the ubiquitous tobruks, were built to the slightly lower B1 standard of 1 to 1.2m, since these structures were partially buried. The designers attempted to minimize the amount of steel necessary in construction, so aside from the steel reinforcing bars (rebar), steel plate and especially steel armour plate was kept to a minimum. A standardized family of small armoured cupolas, doors and firing posts had been developed during the West Wall programme and these were used on the Atlantic Wall as well. Most personnel bunkers and other enclosed bunkers built in 1942–43 were also provided with protection against gas attack both by systems to seal the structure from outside air, as well as filtration systems. Obviously, this was not possible with large gun casemates, but the associated crew bunkers typically had gas protection.

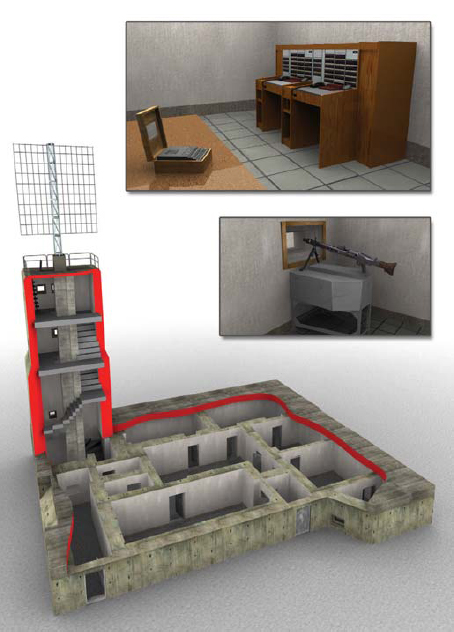

Marine Peilstände und Meßstellen 2 (MP2) (Naval artillery direction and range-finding tower) at Corbiere, Jersey. Despite their rather forbidding external appearance, there was actually very little inside these towers. They sat on cliff tops overlooking the sea and were constructed to house and protect artillery observers operating a system that was soon abandoned due to fundamental flaws in its philosophy. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

One of the more common types of obstacles deployed in 1944 was a simple post obstruction enhanced by adding a Teller mine on top to blow a hole in the bottom of landing craft. In reality, such mines failed as often as not due to the effect of frequent submersion in seawater, symptomatic of Rommel’s slap-dash obstacle program, which argued that ‘something was better than nothing’. (NARA)

The Festungs-Pionier Korps in Berlin designed a family of standardized bunkers for typical applications. Some of these were based on the earlier West Wall programme, but the majority were newer designs. The original West Wall fortifications had been designated in the OB or Vf series for Offene Bettung (open platform) or Verstärkt feldmäßig (reinforced field position). Although some of these designations were retained during the construction of the Atlantic Wall, a new series of designations emerged. There is some disparity in how these designs are identified so for example, the ‘611’ bunker design is variously called Bauform 611 (Construction Plan 611); R611 (Regelbau 611: Construction Standard 611) or H611 (Heer 611: Army 611) to distinguish Army bunkers from Air Force (L: Luftwaffe) and Navy (M: Kriegsmarine) bunker designs. There were about 700 of these standard designs of which about 250 were used on the Atlantic Wall. It should be mentioned that these designs were often modified in the field to better match local terrain contours. Besides the standardized designs, there were localized variations of standard plans as well as entirely new designs, sometimes identified with an SK suffix for Sonderkonstruktion (special design).

Like many of Hitler’s personal passions, the Atlantic Wall was a half-baked scheme. The gnat bites by British commandos along the French and Norwegian coast provoked Hitler into a massive construction completely out of proportion to its tactical value. Hitler had a visceral enthusiasm for monumental fortification after his experiences as a young infantryman in the trenches in World War I. Ironically, it was the Wehrmacht that had demonstrated the futility of linear defences against the combined power of mechanized firepower and air attack. Furthermore, the Atlantic coast was so long that it was impossible to create any defence in depth with the Atlantic Wall, inevitably resulting in a weak and vulnerable configuration.

Rheinmetall 150mm C/36 destroyer gun in coastal mounting. One of the most common naval guns used in Kriegsmarine Atlantic Wall gun batteries was the 15cm Torpedoboots Kanone (Tbts K) C/36. This destroyer gun had been developed by Rheinmetall in the early 1930s, and these weapons were usually deployed in the normal Tbts LC/36 mount which employed a conventional armour splinter-shield covering all of the gun except the rear. (Adam Hook © Osprey Publishing)

When Rundstedt was appointed to head OB West in the spring of 1943, he ordered a comprehensive inspection of the Atlantic Wall defences which took place from May to October 1943. The problem was not so much the uncompleted Atlantic Wall as the continuing drain of resources out of France to the Russian Front. The infantry divisions stationed in France were second-rate static divisions, which were hardly adequate for positional defence. The continued decline in troop quality in 1943 was somewhat offset by continuing fortification of the coast, since it was widely believed by German commanders that the poor-quality troops would be more likely to resist from the safety of bunkers than from exposed field positions.

Under the circumstances, OB West attempted to meld accepted tactical doctrine with the Atlantic Wall fortifications. The resulting tactics were dubbed ‘crust–cushion–hammer’. The Atlantic Wall was the crust that would stop or delay the initial Allied invasion and give the Army time to move its mobile reserves into action. The cushion was the coastal region immediately behind the Atlantic Wall, which would be covered by proposed ‘Position II’ defences. This was a half-hearted attempt started in November 1943 to provide some defence in depth to the Atlantic Wall through a series of field emplacements. Since there was not enough concrete, construction was limited to earthen defence works.

This Rheinmetall 15cm SKC/28 in a coastal C/36 mount with non-standard gun-shield was one of four guns of MKB Landemer, 6./MAA. 260, positioned in an M272 casemate, part of StP 230 in Castel-Vendon to the west of Cherbourg. (NARA)

The St Chamond 155mm K420(f) gun was adapted for coastal defence with a special armoured mount to fully enclose the embrasure. This example is mounted in an H679 casemate of MKB Gatteville of 7./HKAR. 1261 near Cherbourg. (NARA)

In the event, Position II never emerged as a serious defensive programme due to Rommel’s insistence that the emphasis be placed on the initial ‘crust’ of the Atlantic Wall. The ‘cushion’ of the coastal belt also served as a buffer zone since the Panzer commanders did not want to conduct operations near the beaches within the range of Allied warships, based on the lessons of the Mediterranean Theatre, where Panzer attacks were repeatedly demolished by naval gun fire. The ‘hammer’ was the OB West reserve, primarily Panzer Gruppe West under the command of General Freiherr Leo Gehr von Schweppenburg.

With the threat of an Allied invasion of France increasing, even Hitler realized that the Western Front could no longer be ignored. His first action in the autumn of 1943 was to appoint Rommel to command the new Heeresgruppe zur besonderen Verwendung (Army Group for Special Employment; later Heeresgruppe B) to direct the invasion front. Hitler also authorized Führer Directive No. 51 on 3 November 1943, which on paper at least reoriented the strategic priorities for resources and ordered that additional steps be taken to reinforce the Western Front due to the likelihood of Allied invasion sometime in 1944.

The H677 heavy enfilade 8.8cm gun casemate. One of the most fearsome types of defensive emplacements on the D-Day beaches was the H677 gun casemate, armed with the 8.8cm PaK 43/41 towed anti-tank gun. This type of bunker was designed for enfilade fire with a 2m-thick wall protecting its embrasure from the sea. (Hugh Johnson © Osprey Publishing)

Rommel approached his new assignment with characteristic vigour and began a tour of the defences starting in Denmark in December 1943 and working his way down the French coast in early 1944. He came to this new command with a different perspective than most senior Wehrmacht commanders, having spent the past few years fighting the Allies in the Mediterranean Theatre rather than the Red Army on the Russian Front. His last assignment had been the command of German forces in northern Italy. While this did not directly involve him in combating recent Allied amphibious assaults in Italy, he had been involved in the debates over the best approaches to repel the Allied landings. In the case of both Sicily in July 1943 and Salerno in September 1943, the Wehrmacht in Italy had followed the accepted doctrine but it had failed to crush the landings. In both cases, the Allied landings were initially unopposed, but Panzer forces were promptly mobilized and the beachhead attacked in force. In both cases, the mechanized attacks were stopped cold by a combination of tenacious Allied infantry defence stiffened by a suffocating amount of naval gunfire. During the course of his inspections along the Atlantic Wall, the Allies launched yet another amphibious attack against Anzio in January 1944 and, once again, the German mechanized counter-attacks in February 1944 failed with heavy losses. This only served to reinforce his doubts about the current tactics for dealing with Allied amphibious attacks.

Some bunkers were camouflaged to blend into their surroundings like this observation bunker along the seawall in Le Havre. (NARA)

From a tactical standpoint, Rommel rejected the current doctrine and argued that instead of defence in depth with the Panzer divisions kept in reserve away from the beaches, all available resources should be moved as close to the likely landing areas as possible. He believed that the Italian campaign had demonstrated that if the invasion could not be stopped immediately, it could not be stopped at all. He also questioned whether the Allies would actually strike at a port. A landing some distance from a port could lead to the eventual envelopment and capture of the port. In spite of Rommel’s considerable influence with Hitler, his views were not widely accepted by senior German commanders in France. The debate over the best approach to deploying the Panzer divisions continued right up to D-Day and was not settled to the satisfaction of either side in the debate.

From the perspective of the Atlantic Wall, Rommel’s leadership had several important consequences. Rommel invigorated efforts to defend the beaches between the major ports, especially along the Pas-de-Calais and Normandy.

By early 1944, the Kriegsmarine had received the bulk of OT’s resources and the ports had been well fortified. More attention had to be directed to the Army’s shoreline defences. Besides enhancing the fortifications along the coast, Rommel suggested that more attention had to be paid to extending defences out on the beaches. His own experiences in the desert campaign had convinced him of the value of mine warfare and obstacles. Rommel argued that by creating obstructions along the coast, amphibious landing craft would be prevented from reaching the shelter of the shoreline. In combination with enhanced beachfront fortifications, this would create a killing zone along the shoreline. Instead of landing near the protective seawalls so common on the Channel coast, the infantry would have to disembark hundreds of metres from shore, exposed to prolonged fire as they attempted to reach the sanctuary of the shoreline. In contrast to his arguments about defensive tactics, Rommel’s recommendations for improved coastal defence were welcomed by Rundstedt and the other senior commanders who felt that the Army had been too long neglected in the Atlantic Wall construction compared to the Kriegsmarine.

Rommel’s intervention came at an opportune time for the fortification programme. The pace of construction of the Atlantic Wall had fallen off from its highpoint in April 1943 to its lowest point in January 1944 when less than half as much construction was completed. While some of this decline was seasonal, other factors were more important. On the night of 16/17 May 1943, the RAF had breached several of the River Ruhr dams, flooding a portion of Germany’s industrial heartland and knocking out hydroelectric power generators. Speer pledged to Hitler that the OT would clean up the mess as quickly as possible, and so resources were drained out of the Atlantic Wall programme through much of the summer of 1943. Hitler’s new fancy in the autumn of 1943 was the forthcoming V-weapon programme, and a major construction effort was begun by the OT in Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais to create launch sites for the missiles, further undermining the fortification effort. Finally, the pre-invasion Allied air campaign was aimed at crippling the French rail and road networks, and through the late winter and early spring of 1944, OT workers were diverted from fortification programmes to assist in rebuilding the railroads.

To compensate for the shortages of OT construction workers, in 1944 the Wehrmacht began to assign some of the construction work to infantry divisions along the coast. Each of the infantry corps had a Festungs-Pioneer-Stab (Fest.Pi.Stab: Fortification Engineer Staff) assigned to it. These were organized somewhat like a regiment with three attached battalions, but these were administrative units, not tactical formations, and their principal role was to plan and direct the construction of fortifications within their sector. In the late winter and spring of 1944, they were assigned additional troops, often Ost battalions of Soviet volunteers, to help carry out construction work.

The primary work assigned to the infantry troops was to assist in creating the shoreline defences. Since resources were very limited, most of this work involved either the transfer of obstacles from idle defensive works in occupied Europe, or the creation of improvised obstacles using local resources. ‘Cointet’ obstacles, also called Belgian gates or C elements, were large steel-frame devices manufactured in the 1930s to block Belgian frontier roads. ‘Czech hedgehogs’ (Tschechenigelen) – static anti-tank obstacles made from angled iron girders – were collected from Czech forts in the Sudetenland as were similar obstacles found elsewhere in occupied Europe. Similar obstructions were made from scrap metal and concrete including concrete tetrahedrons. One of the simplest forms of anti-craft obstruction was an angled pole, often topped by a Teller mine. During his tour of the defences in February 1944, Rommel was shown a local technique at Hardelot-Plage using fire hoses to dig holes for these stakes quickly, and this technique was widely disseminated through France. Some of this work was too hasty and ill conceived. When some officers decided to test the effectiveness of the stakes using a British landing craft captured at Dieppe, they were shocked to find that the craft simply ploughed through the obstructions with little trouble. As a result, the more substantial Hemmbalk (beam obstruction) was designed resembling a large tripod.

The H667 was the most common anti-tank gun casemate built on the Atlantic Wall, with some 651 constructed in 1943–44, of which 443 were built on the French coast. These were designed to provide better protection than the common Vf600 open gun pits widely used for the pedestal-mounted 50mm gun. This weapon consisted of obsolete KwK 39 and KwK 40 tank guns mounted on a simple pedestal (Sockellafetten) with a spaced armour shield added in front. During 1944, some of these guns were re-bored to fire 7.5cm ammunition. Since the gun was mounted on a fixed pedestal, there was no need for a rear garage door as was so characteristic of other Atlantic Wall gun casemates. Instead, the casemate had a simple armoured door at the rear, protected by a low concrete wall. This bunker, like the H677, was designed to be placed directly on the beach. It was oriented to fire in enfilade along the beach, not towards the sea. The design incorporated a thick wall on one side or other to shield the embrasure from naval gunfire. The interior was very elementary, large enough for only the crew and a few containers of ammunition. (Lee Ray © Osprey Publishing)

The most effective anti-craft device was a Kriegsmarine mine called the Küstenmine-A (KMA; Coastal Mine-A), which consisted of a concrete base containing a 75kg explosive charge surmounted by a steel tripod frame with the triggering device. Although cheap and effective, they became available too late to be laid along the entire coastline. They were first laid along the Channel coast from Boulogne south towards Le Havre since this sector was considered the most likely to be invaded, and this phase was completed in early June 1944. The next area to be mined was the Seine estuary around Le Havre, which was to begin on 10 June, but this never took place due to the invasion. Because of shortages of the KMA mine, the Army developed cheap expedients, the most common of which was the Nussknacker (nutcracker), which consisted of a French high-explosive artillery projectile planted in a concrete base with a steel rod serving as the activating lever. Nearly 10,000 of these were manufactured and deployed in 1944.

Another change in fortification plans in early 1944 was the decision to place all field artillery of the static divisions on the coast under concrete protection, based on the lessons from the Salerno campaign. These casemates were not especially elaborate and were simple garage designs such as the H669 and H612. This programme began in earnest in January 1944.

OB West was very concerned about the possibility of Allied airborne attacks, and several steps were taken to deal with this threat. Large fields near the coast were blocked with poles and other obstructions to prevent glider landings, though in practice this proved to be flimsy and ineffective. In some low-lying coastal areas such as the fields behind Utah Beach and the fields south-west of Calais, the Wehrmacht flooded the fields to complicate exit from the beach. However, many German tactical commanders were reluctant to flood valuable crop fields as local units often depended on local produce to feed their troops and this placed a limit on the extent of deliberate flooding.

The Atlantic Wall consisted of so many strongpoints, gun batteries and other fortified positions that it is impossible in this short survey even to list them all. Instead, some typical examples of defensive positions will be described.

The Kriegsmarine coastal artillery batteries varied in composition depending on the type and number of guns. Some of the naval artillery regiments were composed primarily of heavy batteries. A good example of this was MAA. 244 located on either side of Calais. This unit included six heavy batteries averaging three guns per battery. A typical example was MKB Oldenburg, located immediately east of Calais in Moulin Rouge. This battery was armed with a pair of 240cm SKL/50 guns, which were Czarist 254mm guns captured in 1915 and re-chambered by Krupp. Originally installed in 1940 in open gun pits as part of the Operation Seelöwe build-up, the batteries were substantially improved starting in 1942 with a pair of massive casemates, along with two H621 personnel shelters, a H606 searchlight stand and numerous supporting bunkers. The neighbouring regiment to the west, MAA. 242, had some of the most famous naval batteries including Batterie Todt. Positioned along the high ground of Cap Gris-Nez and Cap Blanc-Nez, this regiment had an extensive array of observation bunkers on the promontories, as well as radar surveillance stations. These two regiments constituted the densest and most powerful assortment of naval coastal batteries on the Atlantic Wall. This heavy concentration was in part due to the strategic decision to heavily fortify the Pas-de-Calais, but the batteries also served to interdict Allied shipping in the Channel.

Most of the other major Festung ports had a similar concentration of naval artillery, though often of less imposing size. A typical battery was MKB Vasouy, the 9. Batterie of Marine-Artillerie-Abteilung 266 (9./MAA. 266) located along the south bank of the River Seine opposite Le Havre on the outskirts of Honfleur. The battery’s mission was to cover the mouth of the River Seine. Its basic armament consisted of four 15cm Tbts.K.L/45 guns, essentially a coastal version of the standard 15cm destroyer gun with an effective range of 18km and a rate of fire of 1.5 rounds per minute. These were enclosed in four M272 Geschützschartenstände (gun casemates) arranged in a line a few hundred metres from the river’s edge. This type of casemate was fairly typical of Kriegsmarine designs but not especially common in France, with only six along the Channel coast and 21 elsewhere including Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands. This particular type was first built in April 1943 and required 760m3 of concrete. The guns were directed from a M262 Leitstand für leichte Seezielbatterie (fire-control bunker for light naval battery) located on a rise on the left of the battery position, connected to each of the four gun casemates by buried electrical cable. Although typical of Kriegsmarine fire-control bunkers, it was not a particularly common type, with only four on the French Channel coast and ten more in the Netherlands. Like most naval fire-control bunkers, it had two storeys with an observation post in the lower level, and an optical rangefinder post on the upper level. Inside the bunker was a control room where the target was plotted and the aiming data sent to the gun casemates. The battery had a single munitions bunker on the other end of the battery site, and two personnel bunkers immediately behind the gun casemates. In 1944, the battery was entirely surrounded by barbed wire, and there were four tobruks armed with machine guns for site defence.

Fortified Army coastal artillery batteries came in three main varieties, the dedicated Army coastal artillery regiments (Heeres-Küsten-Artillerie-Abteilung/-Regiment; HKAA/HKAR) deployed in 1942–44, the fortified divisional artillery battalions and the railway artillery batteries. The Army coastal artillery regiments could be found along many sections of the coast but they were not evenly spread. So, for example, naval batteries dominated the Pas-de-Calais, while Army batteries dominated lower Normandy, including HKAR. 1260 located along the D-Day beaches and HKAR. 1261 on the eastern Cotentin coast to the south-east of Cherbourg. Some of the batteries in these regiments were originally naval batteries such as 3./HKAR. 1261 in St Marcouf and 4./HKAA. 1260 at Longues-sur-Mer, which were absorbed into the Army regiments in 1943 to create a unified command. The most extensive of these was HKAR. 1261, which had ten batteries stretching from St Martin-de-Varreville near Utah Beach along the Cotentin coast to La Pernelle on the outskirts of Cherbourg. In general, these batteries were not as well equipped to deal with moving naval targets as the naval batteries, lacking radars or plotting rooms in their forward observation bunkers. This regiment had some of the best of the Army gun casemates, usually including at least partial armoured shields for the guns. For example, its 7. Batterie located in Gatteville in H679 casemates had their 15.5cm K420(f) guns behind a traversable armoured shield that completely covered the embrasure; the 2. Batterie in Azeville had lighter 10.5cm K331(f) guns, and these had an armoured shield which partially covered the embrasure. These dedicated coastal batteries tended to have an extensive array of support bunkers, including personnel shelters and ammunition bunkers.

Tank turrets mounted on tobruks were a common feature of the Normandy defences and this example of a ‘U’-pattern tobruk with World War I Renault FT tank turret was located near one of the breakwaters in Grandcamp harbour between Utah and Omaha Beach. (NARA)

This plate depicts the turret taken from a French FT-17 tank, captured in great quantities by the German Army in 1940, mounted on a tobruk bunker. Such practice appears to have been a synthesis of Italian and Soviet techniques, the bunkers evolving from tobruk pits, which were named for the area where they were first extemporized by the Italian Army, using concrete drainage pipes vertically emplaced. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

This H677 casemate armed with the formidable 8.8cm Pak 43/41 anti-tank gun formed the core of the WN29 strongpoint near the harbour in Courseulles-sur-Mer and is seen several days after D-Day after Canadian troops had established an anti-aircraft position on top with a 20mm cannon. (Ken Bell, NAC PA140856)

In contrast to the dedicated coastal artillery batteries, the fortified divisional artillery batteries tended to have simpler garage casemates without specialized armoured protection for the embrasure since their weapons were towed field artillery pieces. Supporting bunkers were often less extensive due to the relatively late date of construction of many of these sites, which did not begin in earnest until January 1944. The degree of fortification was quite uneven so for example, the famous Merville Battery attacked by British paratroopers on D-Day had a selection of bunkers comparable to that of dedicated coastal artillery batteries due to the early date of its fortification. Many divisional artillery battalions were not fortified at the time of the D-Day landings.

The Army’s railroad artillery batteries fell out of favour after the 1940 bombardment campaign as rail-guns were withdrawn to other theatres. The Dombunker construction programme was not extended beyond the Pas-de-Calais, and the remaining railroad gun batteries such as those on the Cotentin Peninsula near Cherbourg did not have dedicated bombproof shelters.

Infantry platoon and company strongpoints followed no particular pattern and tended to be constructed on the basis of available concrete supplies, available fortification weapons, and the terrain features of the coast where they were located.

In general, the infantry fortifications on the Atlantic Wall were not as comprehensive as those on the West Wall built along the German frontier in 1938–40. There were two reasons for this, the first of which was the lack of time and supplies to complete any comprehensive fortification of the entire French coastline. The second reason was tactical. Rundstedt and many German commanders were leery of extensive infantry fortification, as they feared it would lead to rigid tactics based around fixed sites. The commanders did not want the infantry cowering in their bunkers while the Allies flowed past the defences, but expected them to get out of the bunkers when necessary and use conventional infantry tactics. As a result, OB West favoured the use of a generous number of fortified machine-gun, mortar and anti-tank positions, but most of the infantry would fight from normal slit trenches. Personnel bunkers were provided for shelter during naval bombardment, but not for fighting.

The 4. Kompanie, Infanterie-Regiment 919, 709. Infanterie Division, provides an example. This company was deployed along the Cotentin coast from St Martin-de-Varreville to Ravenoville, a distance about 4km wide. This sector was a few kilometres to the north of Utah Beach on D-Day. Since German tactical doctrine recommended that a company defend a sector 400 to 1,000m wide, this sector was about four to ten times wider than would be assigned to an unfortified company in normal field conditions.

This company was commanded by Oberleutnant Werner, numbered about 170 men and was deployed in three strongpoints: WN10, WN11 and StP 12. Of the three strongpoints, WN10 on the right flank was by far the largest and most amply equipped. The WN11 strongpoint in the centre was primarily the company headquarters. It had minefields on either side and its principal bunkers facing the beach included two tobruks with 37mm French tank turrets, an artillery observation bunker, two machine-gun entrenchments and a 50mm gun in a Vf600 gun pit. Bunkers within the strongpoint included a mortar and a machine-gun tobruk, and five personnel and munitions bunkers. The northernmost strongpoint, StP 12, was small but heavily fortified and included four tobruks with 37mm French tank turrets, a H612 enfilade casement with 75mm gun, a modified H677 casemate with 50mm gun and a large H644 observation bunker with armoured cupola.

Strongpoint WN10, Les Dunes de Varreville. WN10 was a fairly typical infantry resistance nest containing a mixture of reinforced concrete bunkers and earthen entrenchments. This was one of three inter-related strongpoints manned by 4. Kompanie, Infanterie-Regiment 919, 709. Infanterie-Division, and located to the north-west of Utah Beach, covering an area 600m wide and 300m deep. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

As can be seen from this description, several types of bunkers were very common in these infantry strongpoints. By far the most common were the tobruks, which were not a single type of bunker but rather a generic term for a wide range of small defensive works characterized by a small circular fighting position, hence their official designation as Ringstand. The German version was more elaborate than the Italian original since it generally included one or more compartments for the protection of the crew and for ammunition stowage. They were most often used to create a machine-gun position, but another common variant was a variety of mortar pit for either the battalion 81mm mortars or the company 50mm mortars.

A third common application was to mount the turret from French Renault FT, Renault R-35 or Hotchkiss H39 tanks on the tobruk, all armed with a version of the short 3.7cm tank gun. Another widely used fighting position was the Vf600 gun pit, typically fitted with the 5cm anti-aircraft gun. This was a six-sided open concrete emplacement with semi-protected cavities for ammunition stowage around its inner perimeter. The 5cm anti-craft gun was an adaptation of the obsolete 5cm tank gun mounted on a simple pedestal with a shield added for crew protection. Both the short (KwK 38) and long (KwK 39) versions of the gun were used and a number of these guns were re-bored to fire 7.7cm ammunition. An interesting hybrid of the tobruk and Vf600 was the Michelmannstand, developed by Colonel Kurt Michelmann, the commander of Festungs-Pionier-Stab 27 responsible for fortifying Dieppe and upper Normandy. This was a prefabricated reinforced concrete machine-gun pit that could be rapidly emplaced on beaches or other areas in lieu of more conventional and time-consuming construction techniques. Although it resembled a shrunken Vf600, its tactical application was closer to that of a tobruk.

The gun batteries along the Pas-de-Calais took part in a desultory campaign of bombardment against the English coast around Dover starting in 1940 and continuing well into 1944. This resulted in a continuing campaign of counter-bombardment from British batteries as well as a prolonged air campaign against the ‘Iron Coast’ gun batteries. Although the air campaign was not especially effective in disabling the fortified casemates, the battery sites soon took on the appearance of a lunar landscape due to the many bomb craters. There was also some exchange of fire between coastal batteries and British warships over the years and the heavy gun batteries along the Pas-de-Calais frequently fired upon coastal shipping in the Channel.

The Allied campaign against the coastal batteries was intensified in 1944 and extended to upper and lower Normandy and parts of Brittany in April 1944 as part of the run-up to the D-Day invasion. The campaign was intentionally conducted also at sites other than the D-Day beaches to keep the Wehrmacht guessing where the actual landings would take place. The bombardment campaign had very mixed results, in some cases effectively neutralizing batteries such as the Army coastal battery on Pointe-du-Hoc, in other cases failing to have any appreciable effect on the battery such as at Merville, while other instances had mixed success such as Longues-sur-Mer, where the gun casemates were intact but their performance degraded due to the destruction of the cabling between the fire-control post and the guns.

The D-Day landings in lower Normandy on 6 June 1944 quickly overwhelmed the defences. The coastal batteries with very few exceptions had been disabled before the landings and, even in the case of the few batteries that engaged the landing fleet such as the St Marcouf, Azeville and Longues-sur-Mer batteries, they were quickly suppressed. The only defences that posed a significant problem were those at Omaha Beach, and this was due primarily to the presence of more defences, more and better troops, and a more challenging defence configuration due to the bluffs along the beach compared to the other D-Day beaches.

This 5cm anti-tank gun in an H667 casemate proved to be one of the most effective elements of the WN65 strongpoint covering the E-1 St Laurent draw. It was finally silenced by 37mm automatic cannon fire from a pair of M15A1 multiple gun motor carriage half-tracks of the 467th AAA Battalion. (NARA)

Tobruks were the most common type of fortified position along the Normandy coast, and existed in a wide range of styles. One version of the tobruk commonly seen on the Normandy beaches was the Panzerstellung, equipped with a tank turret. These were sometimes based on the standard Vf67v tobruk as seen here, but also on modified types including a common but non-standard U-shaped tobruk. (Hugh Johnson © Osprey Publishing)

Once the D-Day landings took place, there was no immediate evacuation or weakening of other portions of the Atlantic Wall since senior German commanders remained convinced for several weeks that the Normandy landings were only a feint and that other landings would occur elsewhere along the coast. Elements of the Atlantic Wall defences were involved in continual combat through June as the US First Army advanced up the Cotentin Peninsula, culminating in the VII Corps attack on Cherbourg in late June 1944. Although Cherbourg had been ringed with defences as part of the Festung policy, in reality these defences were not adequate to stop the US Army. The outer crust of Cherbourg defences served to delay the US advance, but they were comprehensively breached within a few days of intense combat. The defences in Cherbourg itself were mostly oriented seaward and so played little role in the city fighting. Indeed, the traditional French fortified defences around the port played as much a role in the defence as did the newer Atlantic Wall defences, such as Fort Roule in the centre of the city and the fortified harbour. The heaviest fortifications, such as the numerous Navy coastal artillery batteries, played little or no role in the fighting since their ferro-concrete carapace limited the traverse of their guns to seaward targets. This experience would be repeated in the subsequent battles for the Channel ports, where most of the work on the Atlantic Wall fortifications proved to be in vain due to this fatal shortcoming.

The Vf600-SK 5cm gun emplacement. One of the most common gun emplacements along the Normandy coast was the open gun platform for the 5cm pedestal-mounted gun. This type was variously called the OB 600 (Offene Bettung = open platform) or Vf600 (Verstärkt feldmäßig = reinforced field position). In its basic Vf600v form, it was an octagonal concrete gun pit about 4.15m wide generally with recesses for ammunition stowage in the four front and side walls. (Hugh Johnson © Osprey Publishing)

Further fighting ensued along the Atlantic Wall after the breakout from Normandy in late July that unleashed the Allied advance along the coast towards the Pas-de-Calais and towards Brittany. St Malo at the junction between lower Normandy and Brittany was the scene of an intense urban battle made all the more difficult for the US Army by the traditional walled fortifications of the port. The assault on St Malo by the 83rd Division began on 5 August and took nearly two weeks of fighting, finally being overwhelmed on 17 August. Even then, German defenders held out on the offshore fortifications of Cézembre until 2 September. The port of Brest was one of the most heavily fortified along the Atlantic Wall and US armoured spearheads began probing its defences on August 7. The city was gradually surrounded and a full-blooded attack began on 25 August by VIII Corps of Patton’s Third Army. Although the fortifications and gun positions of the Atlantic Wall defences played some role in the defence of Brest, for the most part they were not especially useful for the defenders except in some limited sectors. Once again, traditional French fortifications such as Fort Montbarey and Fort de Portzic proved more troublesome than the newer and much smaller Atlantic Wall bunkers, most of which were oriented seaward. As in the case of Cherbourg, the German garrison was eventually overwhelmed, but in the interim, the Kriegsmarine managed to demolish the harbour facilities. As a result, the US Army decided against a direct assault on St Nazaire or Lorient, preferring to simply bottle up the German garrison rather than sacrifice large numbers of infantrymen for a shattered port. The same would be the case along the Bay of Biscay, with fortified ports such as Royan and La Rochelle holding out until May 1945. To reduce the number of US troops assigned to this siege, in the autumn of 1944 newly raised French units were gradually assigned this mission.

While the US Army was dealing with the fortified ports in Brittany, Montgomery’s 21st Army Group was advancing northward toward upper Normandy, the Picardy coast and, eventually, the Pas-de-Calais. The honour of taking Dieppe was given to the Canadian 2nd Division and the city fell without a major fight on 1 September. The second major port in Normandy, Le Havre, was invested by the British I Corps, starting on 3 September. To soften up the defences before the ground attack, the Royal Navy monitor HMS Erebus began bombardment along the coast on 5 September, but was forced to withdraw by the heavy concentration of coastal artillery west of the city. These positions included the only heavy gun battery in the city, a 38cm turreted gun from the French warship Jean-Bart located at Clos de Ronces and supported by the Goldbrunner battery of 3./HKAR. 1254 with three 17cm K18 guns, two of which were in H688 casemates. Besides these batteries, there were several other batteries in the immediate vicinity that took part in some of the subsequent engagements. The Erebus returned on 8 September, but was again forced back by heavy gunfire from the German coastal batteries. Prior to the start of I Corps’ main attack, Operation Astonia, on 10 September, the Erebus returned but this time was accompanied by the battleship HMS Warspite, which demolished the offending batteries with its 15in guns. The two ships then conducted a six-hour bombardment against other coastal fortifications and defences. The battle for Le Havre by two infantry divisions supported by the specialized armour of the 79th Armoured Division lasted only two days in no small measure due to the demoralization of the isolated garrison.

The Longues-sur-Mer gun battery is illustrative of coastal artillery in Normandy. This bunker had the most modern fire-control system of any of the batteries in this sector. It was electrically powered and fed the aiming data directly from the control bunker to the individual gun casemates. This was a two-storey bunker with range-finding and observation equipment, and a target-tracking centre located in the lower chamber. It was connected by landlines to the four M272 gun casemates. The four gun casemates were armed with 15cm C/36 single-mount Torpedoboots Kanonen (destroyer guns), built by Skoda in Pilzen, with a maximum range of 19km. There were ammunition rooms behind the gun chamber, one to contain the powder charges and the other to contain the ammunition. The casemate was protected to Class B standards with walls and roof 2m thick and construction consumed 760m3 of concrete. (Hugh Johnson © Osprey Publishing)

H633 bunker for M19 automatic mortar. The H633 Kampfstand für M19 Maschinengranatwerfer was specifically developed for the West Wall, but by the time that production began in 1940, the requirement had ended. Instead, most were eventually used on the Atlantic Wall, and some 79 were installed in the H633 and H135 bunkers, with 48 on the French coast. The entry way was protected by an armoured machine-gun embrasure and led to the usual gas lock prior to access to the living quarters. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

While Operation Astonia was under way, Canadian forces had begun to probe the outer defences of both Boulogne and Calais. The Canadian 3rd Infantry Division was assigned Operation Wellhit, the assault against Boulogne and the associated German fortifications in the neighbouring hills. In light of the experiences at Le Havre, the specialized armour of the 79th Armoured Division was also used to support the Canadians, especially Churchill Crocodile flamethrower tanks and Churchill AVRE (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineer) fitted with heavy petards. Festung Boulogne had three major concentrations of fortifications: a trio of coastal batteries near Pointe de la Crèche on the coast north of the city, a set of defensive bunkers and a gun battery from 4./AR. 147 on Mont Lambert on the main road into the city from the east, and a series of coastal guns and bunkers on the heights to the south of the port around Le Portel. Besides the defences of the city itself, Operation Wellhit also contained a subsidiary attack on German positions around La Trésorerie overlooking the city to the north-east, which contained the substantial naval battery of Batterie Friedrich August of MAA. 240 with three 30.5cm SKL/50 guns in massive casemates. Operation Wellhit began on 17 September, including an attack by the North Shore Regiment on La Trésorerie and two brigades assaulting toward Mont Lambert. Mont Lambert was not overcome until 18 September after engineers had blasted the final bunkers with explosive charges. The gun casemates of Batterie Friedrich August were stubbornly defended by nearby Flak positions armed with 2cm cannon, but the position was finally overwhelmed on the second day of fighting using PIAT anti-tank launchers and grenades. The Canadians fought into the city and captured the old citadel, but then were faced with the problem of clearing the numerous bunkers on the heights south of the city around Le Portel. These positions had been a constant source of fire through the fighting, with one battery of Flak guns alone having fired some 2,000 rounds in the three days of fighting. This position was finally overwhelmed but fighting for the other bunkers on the high ground continued through 22 September when the garrison finally surrendered. Canadian troops had begun to attack the bunker complexes of La Crèche, but the garrison surrendered before a full-scale attack was launched.

One of the more elaborate mounts for the 5cm pedestal gun was the R600, which had the usual hexagonal gun pit on the top of the structure, but included an alert room and ammunition storage in a chamber below. Normally, this casemate would have been buried in the edge of a coastal dune, but this example on the beach at Wissant has been left stranded by coastal erosion since the war, exposing its interesting shape, including the pair of rear stairways to the gun pit above. (Steven J. Zaloga)

Operation Wellhit led to the capture of about 10,000 German troops at a cost of about 600 Canadian casualties through the use of proven combined tank–infantry tactics that succeeded in the face of a significant number of bunkers and heavy gun emplacements. The capture of the port took six days instead of the planned two days, but the operation involved only about a third of the troops used at Le Havre. The Churchill Crocodile flamethrower tanks proved to be especially useful and an after-action report recorded that most German bunkers surrendered at the first sign of a flamethrower tank. The AVRE tanks were not particularly effective as their petard launcher, although powerful, could not penetrate the 2m reinforced concrete of the bunkers, and this weapon was no more effective than any other tank gun in penetrating the embrasures and armoured doors of the fortifications, if anything being shorter-ranged and less accurate. The aerial bombardment that preceded the attack was not effective in suppressing the bunkers and hindered tank operations in Boulogne due to the craters and rubble. In subsequent operations, such as Calais, the emphasis was shifted to the use of fragmentation bombs to limit the cratering. The fighting demonstrated the limitations of the Atlantic Wall fortifications since the vast majority of defences were oriented seaward. The heavy gun casemates limited the arc of fire of the guns and, as a result, most batteries were unable to take part in the fighting. The few batteries that did have suitable orientations, such as the dual-role Flak batteries designed for enfilade fire along the port, were responsible for the majority of Canadian casualties.

Although consideration was given to simply bypassing Calais in favour of devoting the troop strength to the clearing of the Scheldt estuary leading to Antwerp, in late September Montgomery was persuaded to deal with Calais due to the havoc that its strong gun positions could cause to Allied shipping in the Channel. On the night of 9/10 September, the Regina Rifles took the fortified port town of Wissant and overran the bunkers on Mont Coupole, which offered excellent observation of the Cap Gris-Nez and Calais region.

The most potent fortification to take part in the D-Day fighting was the Crisbeq battery of 3/HKAA. 1261 located near Saint-Marcouf. Only two H683 casemates for its four Skoda 210mm K39/40 guns were completed by D-Day. After engaging in prolonged gun duels with Allied warships off Utah Beach on D-Day, the battery was the scene later of intense ground combat, which earned its commander, Oberleutnant zur See Ohmsen, the Knight’s Cross. (NARA)

The R621 personnel bunker has a tobruk machine-gun pit on one side for observation and defence. This particular type of bunker was the most common type along the Atlantic Wall in France with over 1,000 built including the related R501. This one is part of StP Düsseldorf on the eastern slope of Cap Blanc-Nez, overlooking Sangatte and the Eurotunnel to the right. (Steven J. Zaloga)

Operation Undergo was again assigned to the Canadian 3rd Infantry Division, supported by the 6th Assault Regiment RE of the 79th Armoured Division with their specialized armour. After a series of delays, the attack began on 25 September with heavy tank and artillery support. Batterie Lindemann could offer little resistance as its guns were pointed to sea, and the garrison surrendered at noon on 26 September. Within two days, the two Canadian brigades had cleared through most of the defences to the south-west of the city, while at the same time routes of escape to the east were cut off. Once again, the old French fortifications such as Fort Lapin proved to be more formidable than the scattered German bunkers, and it was taken only after a determined Canadian infantry assault backed by Churchill Crocodile flamethrowers; the same process was repeated at Fort Nieuley. A temporary truce was called on 29 September to organize the evacuation of civilians still in the city.

While the 7th and 8th Brigades were busy in Calais, the 9th Infantry Brigade was assigned to clear the fortified belt along Cap Gris-Nez including the Batterie Todt with its four massive 38cm guns. By this stage the Canadians had a well-orchestrated scheme for dealing with the bunkers; all four of the main German batteries were overcome in a few hours fighting on 29 September and 1,500 prisoners taken at the cost of 42 casualties, with only five killed.

The evacuation of the civilians from Calais only served to further undermine morale within Festung Calais. When the truce ended on 30 September, the defence simply collapsed and the garrison formally surrendered at 1900hrs.

In spite of the enormous numbers of heavy gun bunkers and coastal defences, the landward defences were completely inadequate to hinder a determined attack, especially considering the lack of sufficient infantry in the Festung Calais garrison. The garrison did manage to thoroughly wreck the harbour, and it took more than three weeks to rehabilitate the port.

Unlike Calais and Cap Gris-Nez, Dunkirk lacked long-range gun batteries so Montgomery decided to contain the port rather than waste time and troops capturing it. The Festung Dunkirk garrison numbered about 12,000 troops. Both sides engaged in periodic artillery skirmishes, and evacuation of the civilian population occurred during a truce on 3–6 October. The Czechoslovak Armoured Brigade replaced most of the Canadian troops cordoning the city after the truce. After the German garrison staged a raid on the night of 19/20 October, Operation Waddle was conducted on 28 October to discourage further actions, the last major military action of the siege. The garrison offered to surrender on 4 May 1945, and the town was finally liberated on 6 May.

The Channel Islands were the only part of the British Isles occupied by the German forces, from late June 1940. On 20 October 1941, Hitler – ever paranoid about a possible British attempt to reclaim the islands – ordered their transformation into fortress islands. Under this direction, the Channel Islands actually became one of the most formidable elements in the Atlantic Wall chain, as well as one of the most underutilized. As in the West Wall, the purpose of the defences was to offer an integrated response to any enemy attack, whether from the sea or air or, as was more likely, both. However, unlike the West Wall there could be little in the way of defence in depth; the restricted physical area saw to that.

An enemy approaching the Channel Islands from the sea would first be engaged by the coastal artillery batteries, able to range to some 38km in the case of the heaviest battery on Guernsey, Batterie Mirus. This fire would be directed from the HQ of Seeko-Ki, an abbreviation for Kommandant der Seeverteidigung Kanalinseln (Naval Commander Channel Islands), a command set up in June 1942 which, from October 1942, was responsible for the tactical command of Army coastal artillery and Army divisional batteries firing on seaborne targets, as well as the harbour command and defence flotillas in the three principal islands, in addition to naval artillery.