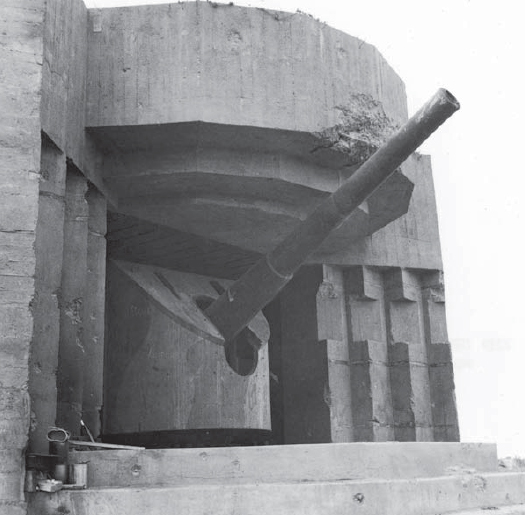

A close-up of an artillery casemate. An American soldier admires the unusual camouflage scheme, which shows more than a little artistic flare. Superficial damage would suggest that the position was involved in some localized fighting or was strafed by Allied aircraft. (NARA)

In August 1943, the President of the United States, the British Prime Minister and the Combined Chiefs-of-Staff met at Casablanca to formulate future Allied strategy. The decisions they took at this meeting related to the whole conduct of the war against the Axis in Europe, but were particularly relevant to the strategy in the Mediterranean. The main aims were to eliminate Italy as a belligerent and to maintain the pressure on German forces to create the conditions for Operation Overlord and the eventual landings in southern France.

By this time Mussolini had been overthrown and, soon afterwards, an armistice was signed with Italy, which only left the final aim of maintaining pressure on German forces. Different people interpreted this in different ways. Certainly Churchill believed that Italy offered an inviting avenue of attack against what he saw as the ‘soft underbelly’ of the Third Reich. And following the Allied landings on the Italian mainland he hoped that Field Marshal Harold Alexander’s Fifteenth Army Group would make a rapid advance up the peninsula. However, geography, history and a resourceful enemy meant that the chances of realizing the Prime Minister’s aspirations were slim.

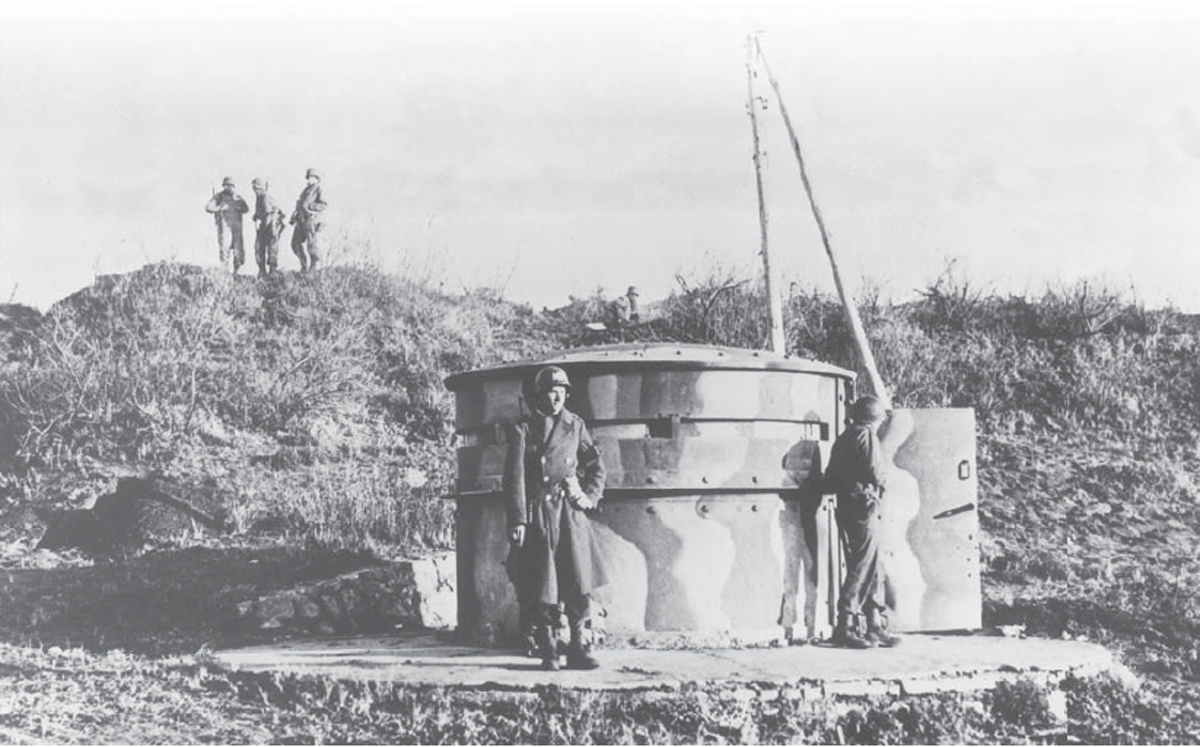

Two Allied soldiers consider the all-round observation afforded by the concrete machine-gun nest in the Hitler Line. Metal hooks set in the roof were used to secure the camouflage net. The timbered entranceway is visible in the foreground leading to the communication trench. (Imperial War Museum, NA 15853)

The view through the aperture of a German pillbox located near San Giuliano. It shows how the position dominated the twisting section of road in front. (NARA)

For someone like Churchill with such a sharp military mind it should have been apparent that the topography of Italy favoured defence. ‘The mountains are rugged and the Apennines make a continuous barrier between the eastern and western sides of the country. Many rivers, some fast flowing between precipitous banks, lie across the path of forces advancing from the south.’ To make matters worse the weather in Italy is often inclement. The summers are very hot, especially in the south, the winters are cold and the spring and autumn are often wet, which gives an attacking army only a short window for operations.

After the loss of Sicily, the German forces had originally anticipated falling back to the Apennines, but Kesselring, the commander of Heeresgruppe C, convinced Hitler of the merit of a stand further south. This would keep the Allies further from Germany; would stop them creating air bases in Italy capable of attacking industrial targets in southern Germany or, more importantly, the Ploesti oil fields in Romania; and would also ensure that the symbolically important city of Rome would not be captured. German forces were rushed south and, having failed to repulse the Allied invasion, they fought a dogged rearguard action. This provided time for engineers, construction workers and labourers to build a series of defensive lines that took advantage of the country’s many rivers and mountains. These were established from the ankle of the boot to its very top and were so numerous that the Germans used almost every letter in the military phonetic alphabet. Indeed in some respects the naming of the various lines seems to have been more taxing for the Germans than it was to construct them. They included letters of the alphabet; names of both sexes from Albert to Viktor and Barbara to Paula; almost all the colours of the rainbow; historical figures from Caesar to Genghis Khan; and, less adventurously, local place names. One line was even named after the Führer himself (although this was soon changed so as to avoid the Allies gaining a major propaganda coup).

German defensive lines in Sicily and Italy, 1943–45.

In the end more than 40 defensive lines were established, but a lack of manpower and raw materials meant that the defences were too few in number, they lacked depth and were often poorly constructed. Yet in spite of this the fortifications did serve to delay the Allies. From the initial landings in September 1943 they took the best part of two years to reach the Alps; this was no soft underbelly but was in fact a ‘tough old gut’.

By the beginning of 1943 the face of the war had changed dramatically for Germany and the other Axis powers. On every front and in every field of combat the Wehrmacht was now on the defensive. In the oceans the U-boats had turned from hunter to hunted, in the air the Luftwaffe had to contend with Allied bombing raids on Germany and on land the Army had been defeated at Stalingrad and was on the retreat in North Africa.

Yet in spite of this reversal of fortune, Hitler was determined not to yield any territory to the Allies. This desire, bordering on an obsession, manifested itself in his insistence that ‘the southern periphery of Europe, whose bastions were the Balkans and the larger Italian islands, must be held’. However, this resolve was complicated by uncertainty over what the Allies’ strategy would be in the Mediterranean. Hitler was of the opinion that Sardinia was the most obvious target for an invasion, while others in the OKW believed they would attack Sicily. These divisions were exacerbated by Operation Mincemeat, a clever deception plan conceived by the Allies to convince the German military that the next attack would be directed towards the Balkans. To make matters worse, Hitler, in theory at least, was still part of an Axis with Fascist Italy and Mussolini was keen to continue the fight alongside his more powerful ally.

In spite of all this uncertainty one thing was clear. The threat of invasion could not be ignored and steps would need to be taken to protect the exposed coastline. However, with the time and materials available it was understood that there would have to be priorities and precedence was given to Sardinia. This decision meant that it was not until March 1943 that the Italians made a concerted effort to reinforce the coastal defences of Sicily. In this task they were aided by German engineers who arrived in the spring of the year and who had themselves been involved in the construction of the Atlantic Wall. Their Italian counterparts, some of whom had been on a fact-finding mission to a number of German coastal positions in France, were keen to create their own version of this great bulwark, but shortages made this difficult and efforts to improve and extend the existing fortifications were disappointing. The three naval bases on Sicily (Augusta, Palermo and Syracuse) were well fortified and were fitted with large-calibre guns, but the situation was very different around potential landing sites. The defences were thinly dispersed and those that existed often lacked weapons and camouflage. There was little in the way of barbed wire, mines or beach obstacles and aerial reconnaissance of one of the British landing beaches prior to the invasion showed a party of bathers.

The Apennines were an extremely strong natural feature, but the Germans still constructed a series of defences along the range and especially through the many passes. This concrete machine-gun shelter was built to cover the road along the Serchio Valley near Barga. (Imperial War Museum, NA21203)

The lack of beach defences was in part the result of a lack of time and materials, but was also partly the result of Italian strategy. The Italian Commando Supreme was of the view that the Allies would attack on a broad front and as such there was limited value in expending a great amount of effort on beach defences. Indeed, General Roatta, the commander of Italian forces on the Island, planned to construct a belt of fortifications and obstacles 19–24km inland – out of the range of Allied ships. These defences were designed to contain any Allied landing until the direction of the main thrust became evident and then the mobile reserve would be employed to decisively defeat them. The German military, by contrast, believed that the only way to defeat an invasion was to hit the enemy when they were most vulnerable and that was when they were coming ashore. In the end the arguments proved academic. The incomplete beach defences did little to stem the Allied landings and the belt of fortifications to the rear seems to have progressed little further than a line on a map.

Having secured their beachheads, the Allies pressed inland. With no prospect of repelling the enemy invasion the Italo-German force had little choice but to make a fighting retreat and now pinned their faith on a series of defensive ‘lines’ that it was hoped would stall the enemy advance sufficiently long to enable an orderly evacuation of the island. The term ‘line’ is somewhat misleading as these were not continuous belts of fortifications but rather were often simply naturally strong defensive positions that were strengthened with mines and fieldworks or demolitions.

The first of these ‘lines’ was the Hauptkampflinie (main defence line), which ran from San Stefano on the northern coast to Nicosia and then south-east to a point just south of Catania and essentially formed the base of a triangle with Messina at the apex. Behind this was the Etna Line (or Old Hube Line), which, as its name suggests, was constructed around the dormant volcano and ran from a point north of Acireale in front of Aderno and Troina to the coast at San Fratello. The troops manning defensive positions along the line would resist until they were in danger of being overrun or encircled before withdrawing along pre-arranged routes to the next position. There were four of these each with shorter bases that required fewer troops to defend; the surplus troops were to be evacuated to the mainland. The first of these was the ‘New Hube Line’, but there was seemingly no agreed set of names for the remainder and nor is it clear who fixed the lines.

The series of defensive lines enabled the German forces on Sicily successfully to evacuate the island across the Straits of Messina to the relative safety of mainland Italy. But the success of the operation could not disguise the fact that the Axis forces had been defeated, and soon after Italy surrendered. No longer able to rely on their ally, the German forces now anticipated pulling back to a defensive line running roughly from Pisa to Rimini. However, haggling over the Italian peace terms delayed the Allied occupation of Italy and gave Hitler the chance to reconsider his strategy. There was already some debate about where the outer boundary of the Third Reich should be and the Allies’ prevarication offered a golden opportunity to set it at the furthest extent possible. Hitler was convinced and rushed 16 divisions south.

These units prepared to repel any invasion force and when the Americans landed at Salerno in September 1943 they were almost driven back into the sea. This success convinced Hitler that there was merit in fighting for Italy and Kesselring, the commander of German forces in Italy, planned to construct a series of delaying positions south of Rome. This strategy had much to commend it, and was not simply based on Hitler’s psychological resistance to giving up territory. First, the Italian Peninsula was much narrower at this point and would need fewer divisions to defend it and, second, it would prevent the Allies capturing the symbolically important city of Rome, along with its airfields.

An Italian concrete pillbox constructed near San Giuliano. The position has a number of apertures that gave it good all-round observation. Rocks have been stacked in front to provide added protection and for camouflage. (NARA)

Before explaining these lines in detail it is worthwhile providing a little background information. Firstly, as in Sicily, the term ‘line’ is something of a misnomer. A line could be a rallying position, a delaying position or a position for protracted defence. Each of these in turn would be fortified according to its role. The rallying position might simply have been a naturally strong defensive position like a river or a mountain range. A delaying position might have some additional fieldworks, while a position for protracted defence might have had some ‘permanent’ defences and be built in some depth. Secondly, there is some confusion about the names of the various lines, which is not helped by the fact that certain names were used twice, and by the Germans’ propensity to change them. To confuse the situation still further, the Allies and Germans often used different names for the same positions.

Initially the defensive lines were identified using the German military phonetic alphabet, for example, the A, A1 and B lines, but later they were given proper names, although often still having the same first letter. The first of these lines was the Viktor Line (A and A1 Lines), which followed the rivers Volturno, Calore and Biferno to Termoli on the Adriatic. Running parallel to this, some 16km to the rear, was the Barbara Line. Both of these lines took advantage of natural features with only light fieldworks constructed, and were simply designed to slow the Allied advance to allow time for the completion of defences further north.

Further to the rear again was the Bernhardt Line (also known as the Rheinhardt or Reinhard Line), which broadly followed the rivers Sangro and Garigliano from Fossacesia to Minturno. This had initially been referred to as the B Line and still followed part of the original line. To begin with it was also only considered as a holding line with light fieldworks, but the decision by Hitler to stand and fight in Italy meant that further work was undertaken and it was reclassified as a permanent position. However, the defences were not uniform and the Eighth Army breached the weaker eastern end of the line at the end of 1943 and a further position – the Foro Line – was established running along the River Foro. By contrast the western end of the Bernhardt Line was particularly strong, especially across the mouth of the Liri Valley where a switch position known as the Gustav Line was constructed.

Plan view of the Hitler Line. The Hitler Line ran southwards from Piedimonte on the lower slopes of the Cairo massif to Aquino and Pontecorvo, and from there via Fondi and Terracina to the sea. The most heavily defended section of the line covered the Liri Valley and part of this is portrayed here, specifically the defences covering the strategically important Highway 6, showing how it would have looked prior to the battle in May 1944. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

The defences of the Gustav Line stretched from Monte Cairo in the north along the high ground to Monte Cassino, then along the east bank of the River Rapido before following the eastern face of the Aurunci mountains. The most strongly fortified section of the line was around the town of Cassino. The River Rapido, with its steep banks and swiftly flowing current, was in itself a formidable obstacle, but on the eastern bank it had been reinforced by a thick and continuous network of wire and minefields, while on the German side carefully sited weapons’ positions and deep shelters to protect the defenders against air and artillery bombardment had been constructed. Additionally, the whole of the fortified zone was covered by mortar and artillery fire, which could be brought to bear with great accuracy from observation posts on the mountains that overlooked the valley from north and south. Armour was kept to the rear for counterattacking or used as static strongpoints.

An excellent view of one of the supporting Pak 40 anti-tank guns that protected the flanks of the Panther turrets. The Panther turret in the rear was destroyed by tanks of the 51st Royal Tank Regiment during the battle for the Hitler Line, May 1944. (Canadian National Archives, PA 114912)

In December 1943, the German troops began to build a reserve position known variously as the Führerriegel (Hitler Line), known later in German communications as the Sengerriegel, 13km to the rear of the Gustav Line. This line ran from Piedimonte, on the lower slopes of the Cairo Massif, to Aquino and then Pontecorvo, and from there via Fondi and Terracina to the sea. Again the most heavily defended section of the line covered the Liri Valley, essentially from Piedimonte to Pontecorvo.

Unlike the Gustav Line, the Hitler Line was not a naturally strong defensive position, and instead relied on an elaborate system of defences constructed by the OT. The defensive belt was between 500 and 1,000m deep. Its main strength lay in its anti-tank defences, which consisted of an anti-tank ditch and extensive minefields covered by anti-tank guns. These included emplaced Panther turrets supported by two or three towed PaK 38 or PaK 40 guns. Approximately 25 self-propelled guns gave depth to the position and also provided a counter-attack capability. All told there were some 62 anti-tank guns covering the 5km front. In support of these anti-tank defences the infantry were provided with deep bunkers built of steel and concrete, each with room for 20 men, which gave them shelter against artillery fire and which were connected with one or two covered emplacements, each mounting a machine gun. Additionally, a large number of semi-mobile armoured pillboxes or ‘crabs’ were installed behind the anti-tank ditch and barbed-wire entanglements. The whole line was covered by approximately 150 artillery pieces together with a considerable number of Nebelwerfer and mortars.

To prevent these elaborate defences being outflanked a series of defences at the western end of the Hitler Line were planned, running from Sant’ Oliva through Esperia and then to Formia on the coast. This was known as the Dora Line. However, Kesselring and his senior commanders had largely neglected these defences because they considered the Aurunci and Ausonia mountains to be all but impenetrable. As a result the extension consisted of little more than minefields and a few simple earthworks dug to block the important roads and tracks. Covering the approaches to the Dora Line, and designed to bar the Ausonia Valley, was the Orange Line, which ran from the River Liri to Monte Civita, but it was similarly neglected.

Behind the Hitler Line, and the last major defensive position before Rome, was the Caesar Line. The main portion of the line ran from the coast just north of the Anzio bridgehead via the Alban Hills to Valmontone with the main fortifications concentrated on the coastal strip, Highway 6 and a number of other minor roads that led to Rome. The defences were cleverly sited to take advantage of the natural defensive features, but resources – materials, men and time – were scarce and they were far from complete when the Allies attacked.

German defensive lines in central Italy, 1943–45.

Not surprisingly the Caesar Line did little more than delay the Allied advance and on 5 June the Americans entered Rome. There was now only one major prepared defensive position before the Alps and that was the Gothic Line. Preparation of this position had begun when Italy surrendered and had continued intermittently thereafter, but it was not until June 1944 that work began in earnest.

The lack of progress prompted Hitler to change the name of the position from the Gothic Line to the Green Line. The original title was considered too pretentious and gave the impression that a strong fortified position existed, which was not the case. If the line was to be of ‘fortress standard’, as Hitler hoped, more time would be needed to complete the defences and that meant that Kesselring’s forces would have to continue to fight further south. This would not only buy valuable time to finish the work but would also deny the Allies new air bases and limit the room they had to launch an amphibious operation from Italy, perhaps against the Balkans.

To realize these aims a further series of lines was established. The first of these was the Dora Line, which was a rallying position north of the Eternal City that ran to the eastern end of the Caesar Line. Behind this was ‘Line E’, which was a delaying position designed to slow the Allies before they reached the main line of defence – the Albert Line. This snaked from Ancona on the Adriatic to Perugia and then on to Lake Trasimeno before following the River Ombrone to the coast.

Behind the Albert Line were further delaying positions on the west coast, notably the Anton and Lilo lines that protected Leghorn and Siena respectively. And behind these lines, designed to protect Florence and the Arno crossings, were the Olga and Lydia lines, these running from Montopoli in the west to Figline on Highway 69. These positions, together with the Georg Line, a further intermediate withdrawal line that covered Volterra and Arezzo, would allow the German forces to fall back in good order to the next, and last, defensive line before the Green Line, the Heinrich Line. This started at Pisa on the west coast and ran along the north bank of the Arno and followed the line of the Apennines until it reached the coast at Senigallia.

Immediately in front of the Green Line were two further defensive positions that formed the outer bulwarks of the main line. The Vorfeld Line was a deep outpost zone that started at Fano on the Adriatic and followed the Metauro to its source in the Apennines and then on to a point just east of Florence where it effectively merged with the Heinrich position; behind this was a further intermediate position called the Red Line.

The ‘Green Line’ in actual fact consisted of two separate positions. Green I ran from Pesaro in the east to La Spezia in the west and Green II ran parallel to the first some 16km to the rear, but only as far as the Futa Pass where the two merged. At the rear edge of the Green Line was the Rimini Line. As its name suggests it was anchored on the Adriatic at Rimini and followed the River Ausa to the principality of San Marino. The value of these lines had long been recognized because they offered the last chance of a defensive action on a comparatively short front while at the same time taking advantage of the Apennine mountains, which at this point stretched from the Ligurian Sea almost to the Adriatic. If there was time to properly fortify and man these positions it was hoped that an attack on them would so weaken the enemy in a battle of attrition that further enemy operations would be much reduced or have to be cancelled completely. Moreover, it was important that the Apennine position was held because behind it lay the Plains of Lombardy. This flat expanse was perfect for large-scale operations and was rich in agriculture. An Allied breakthrough here would mean that extra food supplies would need to be provided for German forces in Italy and would also mean the loss of the industrial output from the Milan–Turin industrial basin.

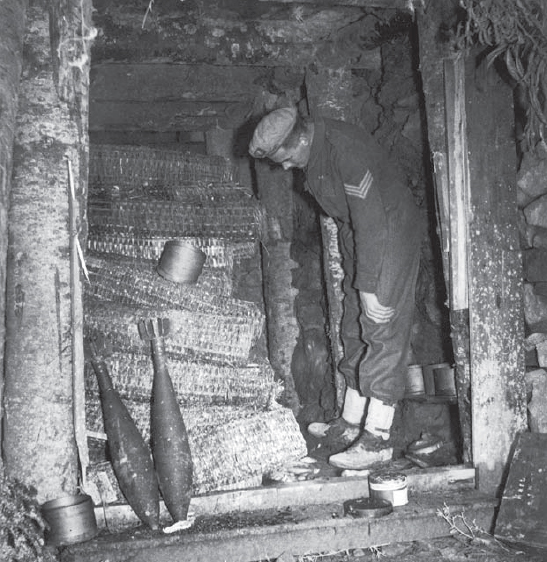

In order to safely store their ammunition for the weapons employed along the Gothic Line the Germans blasted a number of caves in the mountains. This cave was located near Castiglione Dei Pepoli. It was 5m deep and strengthened with timber props. It was used to house mortar rounds, as shown, and 17cm artillery shells. (Imperial War Museum, NA 19204)

The ramifications were unthinkable but eminently possible and even before the completion of the Apennine position a final defensive position had been identified – the Voralpenstellung (Forward Alpine Defences) – and in front of this a series of rallying and delaying lines were instituted. These intermediate positions were established along the line of the numerous fast-flowing rivers that ran from the Apennines, across the path of the Allies’ advance, to the Adriatic. On the River Savio was the Erika Line and behind that on the Ronco was the Gudrun position, which protected Forli and blocked the Via Emilia (Route 9), one of the main arterial roads. Next came the Augsberger Line, which ran along the rivers Montone and Lamone and protected Ravenna. After that was the Irmgard Line, which followed the Senio, the Laura Line running along the Santerno, the Paula Line along the Sillaro and the Anna Line, which hugged the Gaiana.

In October 1944 a further defensive line east of Bologna was established. The Genghis Khan Line, as it was known, ran from Lake Comacchio along the River Idice to the foothills of the Apennines. This formed the forward line of a position that had already been prepared along the River Reno and which was sometimes referred to as the Reno Line.

An example of a reinforced shelter constructed inside a house in the Hitler Line. This example was constructed on piers which shouldered steel girders and logs. On top of this framework masonry and rubble were poured to a thickness of some 65cm. One of the entrances to the house was blocked with barrels filled with stones. (Public Record Office, WO291/1315)

The last line of defence before the Voralpenstellung was what the Allies referred to as the Venetian or Adige Line and what the Germans called the Red Line. This ran along the River Adige to the southern tip of Lake Garda.

The Voralpenstellung (also known as the Blue Line) was begun in July 1944 and included in its arsenal coastal artillery taken from the Ligurian Coast. The line ran from the border of Switzerland, across the Julian Alps to Monfalcone and was tied in with a series of defensive lines that ran along the rivers Brenta, Piave, Tagliamento and Isonzo that were to block the so-called Ljubljana Gap. The defences on the last two rivers were much more advanced and there were plans to emplace Panther tank turrets here in much the same way that they had been in the Hitler lines.

Technically speaking the National Redoubt, or Alpenfestung (Alpine Fortress), lay outside of Italy, but it warrants a brief mention for completeness. The Gauleiter for the Austrian province had floated the idea of a last redoubt in the Tyrolean Alps. Some work on the defences did begin but shortages of men and material, which had bedevilled previous attempts to build defensive lines in Italy, were now more acute and only a few fortifications on the Austro-Swiss border were completed.

Also worthy of mention are the fortifications constructed by the Italians and inherited by the Germans. Before World War I, defences had been constructed on the Ligurian Coast to meet the possible threat from France, but when Italy joined the Triple Entente this threat disappeared and in World War I these defences were largely abandoned and the weapons transferred to the front with Austria-Hungary. After the war the coastal defences were steadily improved with the building of a series of medium artillery batteries. These were subjected to a number of attacks by French and British naval forces in the early part of World War II and the weakness of the defences was highlighted, in particular the lack of any large-calibre artillery pieces. This shortcoming was rectified with the building of a number of large coastal batteries, but ironically these were not tested before the Italian surrender and the defences fell into the hands of the German forces. Some renovation and improvement work was undertaken by the OT, much of which was completed in a burst of activity in the spring of 1944 when there was a very real possibility of an Allied landing. This principally consisted of work to build obstacles and casemates to enfilade the beaches and also efforts to strengthen open positions against air attack. As it transpired the Allies landed in southern France and the defences of the rather grandly named Ligurian Wall were abandoned and the garrisons were relocated to France or to the Green Line. Ultimately, the only action the defences saw was against local partisans and in April 1945 the troops that remained surrendered to the Americans.

The other major defensive position inherited from the Italians was the Vallo Alpino. Ironically much of this had been constructed to deter an attack by Germany and as such most of the defences were of little use against an enemy attacking from the south. However, this was not true of the Ingrid Line, which ran along the Italian border with the former Yugoslavia. The defences here were strengthened by the OT with the addition of standard shelters and fieldworks against a possible Allied invasion of the Balkans, or, as became increasingly likely, a possible Soviet attack.

At an operational level each of the lines, and certainly those designed for protracted defence, were constructed in depth. At the leading edge were minefields, barbed wire and anti-tank ditches. Behind these defences were machine-gun and anti-tank positions that covered the line throughout its length. Further to the rear artillery, rockets and mortars were registered on the expected routes of advance. The idea was to separate the infantry and the armour and to isolate the attackers from their own forces, so making them vulnerable to counter-attack by reserves held in the rear, sheltered against the preliminary air and artillery bombardment, and earmarked for the purpose.

American soldiers inspect a section of the anti-tank ditch of the Gothic Line. The technique for revetting the sides is clearly evident with uprights held in place by wire securing the brushwood behind. (NARA)

Defensive lines had already been used in Sicily and in the early part of the campaign on the mainland. However, these lines tended not to be continuous and they certainly were not constructed in depth. The first real example was the Gustav Line. Here the River Rapido provided a difficult natural obstacle for any attacker to negotiate and this had been strengthened with the addition of mines and barbed wire. Behind these machine guns had been sited to provide interlocking fields of fire, especially around the most likely avenues of approach. Frequently these were housed in armoured pillboxes, which were known to the German forces as MG-Panzernester and to the Allies as ‘crabs’. These firing positions were often linked to troop shelters at the rear. These were either prefabricated steel shelters or constructed from concrete with some large enough to contain sleeping accommodation for 20 or 30 men. Further to the rear mortars, Nebelwerfer and artillery were located to provide indirect fire support.

An Italian Cannone de 75/46 pressed into service by the Germans. This position was captured by the Allies north of Cervia and covered dragon’s teeth on the coast below. The embrasure has been strengthened with the addition of sandbags. Ammunition ready for use is stacked to the side. (Imperial War Museum, NA20021)

An army observation post for a coastal battery (Type 637) positioned on the west coast. This example was only just completed when US forces captured it. The wooden shuttering is still in place on one side and is also evident in the foreground. (NARA)

In the town of Cassino itself and on the surrounding slopes a very different approach had to be adopted. Here the closely packed buildings meant that a traditional defensive position was not possible. Moreover, the heavy fighting and later Allied bombing had flattened many of the buildings. Far from being a handicap for the paratroopers assigned to this section of the line, this was a positive boon because, as the German troops knew from bitter experience at Stalingrad, rubble makes a better defensive position than undamaged buildings. Wherever possible shelters were constructed on the ground floor or in the cellars of buildings. These shelters were walled and roofed with heavy logs or girders and covered with a thick layer of rubble, which made them impervious to direct hits even from large-calibre artillery shells. Tanks and self-propelled guns were also positioned inside the shells of buildings as improvised strongpoints and proved extremely effective.

To the rear of the Gustav Line was the Hitler Line. This was not a naturally strong defensive position and as such German engineers went to great lengths to construct a continuous line of defences in some depth. With little time to complete the work a simple anti-tank ditch was blasted along the length of the line. In front of this was a thick band of barbed wire sown with mines. Behind these passive defences were machine-gun positions and, for the first time, Panther turrets mounted on steel shelters were used. These were positioned in a single defensive line in such a way that they were able to cover the line throughout its length. They were deployed in a series of spearheads. At the tip of each spear there was a Panther turret and echeloned back on either side were two or three towed 7.5cm or 5cm anti-tank guns. The turrets were located so that they commanded the approaches to the line with particularly long fields of fire to their front where trees had been cut down to approximately 45cm from the ground. They had more restricted fields of fire to the flank and particularly the rear, and towed anti-tank guns covered these weak spots. These were generally employed in pairs approximately 150–200m behind or to the flank of the turrets and were often hidden behind houses, in sunken roads or in thick cover. Some 25 self-propelled guns were also positioned along this same line with some held further to the rear to give depth to the defences, or to provide the punch for any counter-attack.

The Caesar Line was to be constructed in much the same way as the Gustav and Hitler Lines, but because resources had been diverted south, work on the line was far from finished by the end of May. The defences protecting Rome were largely complete though with thick bands of barbed wire and mines laid to block the most favourable routes of approach. Covering these defences were machine-gun and anti-tank positions; mortars, Nebelwerfer and artillery provided indirect fire support. However, as General Eberhard von Mackensen, the commander of 14. Armee, was quick to point out, ‘the Caesar Line was suitable for no more than a delaying action’.

The Gothic Line, or Green Line as it was later known, was the last major defensive line before the Alps. The Italian Army had identified the potential of a line running roughly from Pisa to Rimini and the merits of such a position were not lost on the OKW. Work on the defences had begun in late 1943, but had been suspended to concentrate resources on the Gustav and Hitler lines. Only in the summer of 1944 did work resume.

A rare photograph of one of the dug-in Panther tanks used by the Germans in the Gothic Line. Polish forces captured this example. The driver’s and machine-gunner’s hatches of the Ausf. A are clearly visible in the foreground. It is also possible to see the tank’s original Zimmerit anti-magnetic-mine paste covering. (Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum)

The position was immensely strong, incorporating as it did the mass of the Apennines and a number of rivers that had their source in the mountains and flowed to the Adriatic. There were weak points, the principal one being the coastal plain around Pesaro, and this is where the bulk of the defences were concentrated. This was the responsibility of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s 10. Armee and in this section of the line alone it was planned to lay more than 200,000 mines (although by the end of August 1944 less than half had been completed – 73,000 Tellerminen and 23,000 Schrapnellminen). A continuous anti-tank ditch almost 10km long had been dug and almost 120,000m of barbed wire had been used. Covering the line were almost 2,500 machine-gun positions, including MG-Panzernester and PzKpfw I and II turrets adapted for static employment. Panther turrets were also used, with particular concentrations in the section of the line that ran along the River Foglia from Pesaro on the east coast to Montécchio. By the end of August four of these positions had been completed in this section of the line with a further 18 under construction. In addition, seven disabled Panther tanks had been dug in with another one being installed. There were also almost 500 positions for anti-tank guns and Nebelwerfer and some 2,500 dugouts of various types, including OT steel shelters.

There had been little time to build the defences in any great depth and indeed Green II was little more than a reconnoitred line on German staff maps, although its natural features were strong. Panther turrets were installed to the rear, but this seems to have been the only attempt to provide depth to the position. As for possible outflanking manoeuvres, on the Adriatic Coast, which Kesselring regarded as the most vulnerable of the two, dragon’s teeth were constructed on the beaches, laced with barbed wire and mines, to counter another Allied landing. Large concrete bunkers were also constructed to house coastal artillery.

The western section of the Gothic Line was dominated by the Apennine mountains and as such offered fewer opportunities for an Allied breakthrough. The weakest point was along Route 65 through the Futa Pass and it is here that General Joachim Lemelsen, the new commander of 14. Armee, concentrated his defences. The outpost zone consisted of minefields, an anti-tank ditch and barbed-wire entanglements. Behind these were fire trenches that covered the line throughout its length. Further to the rear were concrete pillboxes, troop shelters and the much-feared emplaced Panther turrets. One was installed close to the village of Santa Lucia, guarding the long anti-tank ditch dug a few kilometres south of the pass, and another on the pass itself. Similar defences were also constructed on Highway 6620 to the west, the Prato–Bologna road, and to protect Il Giogo Pass to the east, although both lacked Panther turrets. A Panther turret was installed at the Poretta Pass to protect Route 64 above Pistoia.

The last of the major defensive lines was the Voralpenstellung, which was constructed in north-eastern Italy to block the so-called ‘Ljubljana Gap’. According to German files this position was to be heavily fortified, with plans to install 30 tank turrets mounting machine guns, 37 Panther tank turrets, 100 Italian M42 tank turrets fitted with a German 3.7cm Kwk and 100 P40 turrets fitted with a German 7.5cm Kwk. It was also envisaged that a significant number of tank guns fitted to improvised mounts would be installed. However, it is unclear how many of these defences were completed. Certainly a number of the Panther turrets were being installed by January 1945, but others were destroyed or delayed in transit.

Plan view of a section of the Gothic Line. This plate depicts a small section of the Gothic Line that ran from Pesaro on the coast inland to Tomba di Pesaro and to the rear to Cattolica. The defences are depicted as they were planned in the autumn of 1944 and demonstrate the German concept of defence in depth. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

For all the effort that went into the construction of the various defensive lines in Italy, they failed to stop the Allied advance. This judgement might seem harsh, because they certainly helped to delay the progress of 15th Army Group. However, it must be remembered that Alexander’s forces were never significantly larger than those fielded by Kesselring and he certainly did not enjoy the 3:1 advantage that was considered necessary for a successful attack on such prepared positions. And yet in spite of this fact the Allies were still able to breach the defences. True, Alexander could field more armour and artillery, but these advantages were of less significance in a mountainous country like Italy. The same cannot be said of air power and this highlights one of the major shortcomings of such defences. They are by their very nature static and therefore vulnerable to attack from the air. Allied tactical and strategic bombing raids meant that work on the defences was constantly interrupted by direct interdiction or by delays in the supply of materials. This, together with sabotage and a less than committed workforce, meant that many of the defences were not complete or were sub-standard. Moreover, unfettered air observation meant that Allied ground forces always had good intelligence on enemy defences, despite the fact that much of the work was undertaken at night and camouflaged during the day.

An aerial view of a section of the Voralpenstellung east of Gorizia. The arrows indicate anti-tank gun emplacements. ‘A’ shows a belt of dragon’s teeth. ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’ are anti-tank ditches. (TM30-246 Tactical Interpretation of Air Photos 1954, Figure 208)

The poor state of the defences also undoubtedly lowered the troops’ morale. Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry made much of the strength of the defences, but its highly coloured description of the defences often did not match the reality. Indeed Engineer General Bessell, when taking over responsibility for the Gothic Line at the end of June, noted that,

The line was without depth, lacked emplacements for heavy weapons, and was little more than a chain of light machine-gun posts. Fields of fire had not been cleared, anti-tank obstacles were rudimentary and the ‘main line’ ran across forward slopes.

And even where the defences had been completed there were often insufficient troops and weapons to employ in the positions. As Machiavelli famously stated, ‘fortresses without good armies are incompetent for defence’. Furthermore, the rigid defences in many respects reduced the scope for the soldier on the ground to use his own initiative that had been such an important part of the German Army’s early success.

At a strategic level the major problem with such defensive lines on the Italian Peninsula was that they could be outflanked by amphibious assault. In January 1944 VI (US) Corps landed at Anzio almost unopposed and had the chance of outflanking the Winter Line and capturing Rome. Overcautious commanders on the ground saw this opportunity squandered, but the prospect of a further landing was never far from the mind of German generals. These fears did diminish following Operation Overlord in June 1944 and certainly after the landings in southern France in August 1944, because it was recognized that the number of landing craft available to the Allies was finite. However, there was still concern about a possible landing on the Adriatic Coast and as such it was never possible to have complete faith in any defensive line, no matter how strong, for fear of it being outflanked by a landing in the rear.

Each of the defensive lines built by the German soldiers in Italy was unique, built as they were to take advantage of natural features specific to that area, but often they shared common characteristics. The outpost zone consisted of passive defences: barbed-wire entanglements, minefields and, where there was no river or similar feature, an anti-tank ditch. Covering the whole were machine-gun positions, often mounted in MG-Panzernester or tank turrets, and to provide anti-tank defence Panther turrets were installed. Exceptionally, a number of other defences were constructed. Dragon’s teeth, which had first been used along the West Wall, were installed along the coast, and further inland large coastal guns were mounted in concrete casemates. Finally, in the last desperate days of the war there were plans to use tank guns mounted on swivel mounts as improvised anti-tank guns.

The coast near Ravenna was fortified with pillboxes and protected with wire and, as seen here, dragon’s teeth and mines. The mines are probably Italian anti-tank mines in wooden cases and were lifted by sappers to enable an airfield to be constructed nearby. (Imperial War Museum, NA 20897)

Along the length of the Hitler Line, Panther turrets mounted on specially designed shelters were installed. One of these turrets covered the strategically important Highway 6, which led from Monte Cassino to Rome. The turret, taken from a Panther Ausf. D tank, was positioned just behind the anti-tank ditch and wire and would have been heavily camouflaged but this has been omitted for clarity. At the front of the position was a shallow sandbag trench that was just deep enough for the gun to be depressed into so that it did not cast a telltale shadow for Allied aircraft to spot. The turret was mounted on an OT steel shelter that was buried in the ground and encased in concrete 1–1.5m thick. The shelter itself was constructed in two parts. The upper box incorporated the turret ball-race and housed the ammunition for the main armament. The lower structure was divided into three compartments. The largest of these was fitted with nine fold-down bunk beds and a stove for heat. In the right-hand rear corner of the compartment there was an escape hatch. The second compartment acted as home for a 2hp motor, together with a dynamo, a storage battery and a compressed air tank. The final compartment was fitted with a steel ladder that linked the upper and lower boxes and also incorporated the main access hatch. From here a revetted trench led away from the shelter. This was 60cm wide and 1.3m deep and ran to an abandoned building located on the Aquino road. Approximately two-thirds of the way along the trench was an ammunition shelter. This was 2.6m square and 1.3m deep and was covered with timber and spoil. This is shown separately in cutaway. All around the position was a barbed-wire fence. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

Two types of mine were employed: Tellerminen, which were used against vehicles, and anti-personnel mines. The mines tended to be laid in rectangular blocks to cover expected avenues of attack or, in the case of Tellerminen, they were often laid along roads and tracks. The weight of the vehicle would detonate the charge. The same principle applied to the Schützenmine 42, or ‘Schu Mine’, which was one of the most widely used anti-personnel mines. This consisted of a plywood box packed with 200g of TNT. Pressure on the lid would set off the charge. Because it was in a wooden box it was exceptionally difficult to detect. Captured Italian models were also employed and these were equally hard to find in Sicily because of the high iron content in the rock and lava. The Schrapnellmine 35 was slightly different. This was activated by direct pressure on the head or by use of trip wires. A small charge would then propel the mine into the air where it would explode, scattering shrapnel over a wide area.

An Allied soldier inspects one of the flamethrowers that were used in the Gothic Line. The fuel tank of the Abwehrflammenwerfer 42 was buried in the ground so that only the nozzle was visible. They were often used in groups and when triggered would project a jet of flame for some 50m. (Imperial War Museum, NA 18338)

Often minefields were enclosed within a double-apron barbed-wire fence. This generally consisted of rows of concertina wire or wire stretched between screw pickets. Behind this, stretched just above the ground, was a broad band of trip wire.

In the absence of a river or similar anti-tank obstacle it was necessary to construct a man-made alternative. In the Hitler and Gothic lines anti-tank traps or Panzerabwehrgraben were dug. These varied in length and sophistication. In the Hitler Line this was little more than a consecutive series of craters that had been blown electronically with demolition charges at about 5m intervals. Accordingly, the width of the ditch varied from 7m to 11m and the depth from 2m to 4m. Only in a few places had any additional spadework been done. In a number of instances the explosive charges had not detonated and as a result there were irregular gaps in the ditch. A more elaborate affair was constructed at the eastern end of the Gothic Line running inland from the coast. It was dug to a depth of 2.5m, which with the spoil meant that the overall depth was 3m, and was 4.5m wide. It was revetted with logs and brushwood held in place with anchor wires secured to stakes that were buried to protect them against enemy artillery. For every kilometre dug some 6,200m3 of soil had to be removed.

Two Allied servicemen inspect a captured MG-Panzernest. The steel door, which was hinged at the base, lies flat on the floor. The position is perfectly located to enfilade one of the beaches south of Rimini where the Germans anticipated an amphibious landing. Just visible in the distance are stakes and barbed-wire entanglements. (Imperial War Museum, NA 18995)

Covering the outpost zone were a variety of weapons. One worthy of mention because of its uniqueness was the Abwehrflammenwerfer 42, which was dug in at ground level in forward posts of the Gothic Line. This weapon was based on a Soviet design first encountered by the German soldiers in the Stalin Line. The 22.7-litre fuel tank was buried in the ground so that only the nozzle was visible. They were often used in groups spaced 10–25m apart and were ignited by a fuse or a trip wire. This would trigger a 50m jet of flame that lasted 5–10 seconds.

More normally the passive defences were covered by various machine-gun positions, including the MG-Panzernest. This was developed in the second half of the war and proved invaluable when the German Army was on the retreat. Weighing just less than 3,200kg it could be transported and installed relatively easily and provided valuable protection for the two-man crew against enemy small-arms fire and shrapnel.

The nest was constructed from two steel prefabricated sections that were welded together. The top half contained the aperture for the gun, air vents and the rear entrance hatch, which was hinged at the base. This section was most vulnerable to enemy fire and was cast accordingly with armour around the aperture 13cm thick and 5cm around the sides and the roof. The base of the unit, which was completely below ground, was about 12.5mm thick.

The frontal aperture was divided into two parts: the lower part accommodated the gun barrel and the upper part was for sighting. Two periscopes in the roof provided further observation. When not in use the aperture could be covered with a shield operated from within the shelter. The relatively small aperture meant that the machine gun had a limited field of fire of approximately 60 degrees. Because of this and because the nest could not be rotated they tended to be used for flanking fire with other positions providing mutual support.

A simple foot-operated ventilation system was provided that used holes at the side of the turret. These also acted as the mounting for an axle. With the nest upside down wheels could be fitted on either side. A limber was attached to the machine-gun embrasure and two further wheels were located in front. This was then hooked up to a tractor and the whole could then be towed.

Machine guns were also fitted in old tank turrets mounted on concrete bunkers. These were built to a standard design. Directly below the turret was the fighting compartment. This was fitted with wooden duckboards, which not only improved the crew’s footing but also served as a repository for spent machine-gun cases. Any water that entered the fighting compartment would also collect here before being channelled through a drain to the lower level, where the floor was angled at 2 degrees to direct water out of the shelter to the soakaway at the entrance. Access to the fighting compartment was via a flight of steps from the anteroom inside the entrance, which in turn was linked to a revetted trench at the side. This room also housed the hand-operated ventilation system.

Turrets were taken from a number of obsolete German tanks. These included a number of modified PzKpfw I turrets. The original mantlet was removed and replaced with a 20mm-thick plate with openings for the machine gun and the sight. The two vision slits in the turret side were dispensed with and were covered by 20mm steel plates which were welded over the openings as ventilation ports. This meant they were much better suited for their new role. A number of PzKpfw II turrets were also used and a similar number of Czech PzKpfw 38(t)s were also made available for use in the Gothic Line.

There were also plans to use large numbers of Italian tank turrets that had fallen into German hands following their occupation of the country. These turrets were to be mounted on specially designed concrete bunkers (although a wooden design was also later developed). There were plans to install 100 P40 turrets and 100 M42 turrets in the Voralpenstellung, but it is unclear as to whether this work was completed. A number of other Italian tanks were simply dug in and used as improvised strongpoints. P40 tanks were used in this way in the Gustav Line and at Anzio when work to replace its unreliable diesel engine proved problematical; a number of L3 tankettes were used in a similar fashion.

One of the numerous MG-Panzernester, or ‘crabs’, used in the Hitler Line. This example was captured before it could be buried in the ground. Still attached at the front is the limber and a shattered wheel. The whole structure would have been towed upside down. (Imperial War Museum, NA 15778)

A cutaway view of a PzKpfw II turret. In addition to the heavier Panther turrets, a number of PzKpfw II turrets were installed along the Gothic Line. The view shows the steps leading from the trench down into the shelter and then the steps leading up into the fighting compartment. This was fitted with wooden duckboards, which served as a makeshift repository for the spent shell cases. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

In addition to the tank turrets, ten specially designed armoured revolving hoods (F Pz DT 4007) were installed capable of mounting either an MG34 or an MG42. These were constructed from steel plate, but were sufficiently light to be man portable. They could be mounted either on a prepared concrete or wooden shelter or, if necessary, simply on firm ground.

These, and the other tank turrets, were primarily for use against infantry, but a large number of Panther tank turrets were also used as improvised fixed fortifications. They retained their powerful 75mm gun and were often the main anti-tank weapon in the defensive line. The turrets were either taken from production models (Ausf. D and A) or specially designed for the role. The Ostwallturm (or Ostbefestigung) as it was known, differed from the standard turret in a number of ways. The cupola was removed and was replaced by a simplified hatch with a rotating periscope, and the roof armour was also increased in thickness because of the greater threat to the turret from artillery fire. The turrets were mounted on either concrete bunkers or, more often, on steel shelters. The OT had developed a series of prefabricated steel shelters and one of these was adapted to mount a Panther turret. It was constructed in two parts from electrically welded steel plates. The upper box essentially formed the fighting compartment. It held the ammunition for the main weapon and incorporated the turret ball-race onto which the turret was mounted. The lower box was divided into three compartments. The largest formed the living accommodation and was fitted with fold-down bunk beds and a stove. A further room acted either as a general store or as home to various pieces of equipment that provided power for the turret and shelter. Finally, there was a small anteroom fitted with a steel ladder that linked the upper and lower boxes and was also where the main entrance was located. A revetted trench, covered near the entrance, led away from the shelter and linked it to the main trench system at the rear.

A Panther turret and steel shelter ready for installation. In the foreground are the rails on which the lower box, which formed the crew’s living quarters, was moved into place. The two sections have been covered in hay in an effort to camouflage them. (Imperial War Museum, NA 18343)

A large number of the original steel shelters developed by the OT were also installed in the various lines to provide protection for troops against enemy artillery and air attack. Other shelters were constructed from timber with soil and rocks heaped on top for added strength. These different shelters were often linked to fighting positions mounting a variety of weapons including machine guns, mortars, Nebelwerfer, artillery pieces and anti-tank guns.

Later in the war, there were plans to install tank guns in open pits as improvised anti-tank positions. The powerful 8.8cm guns taken from Jagdpanther tanks were to be fitted to pivot mounts and 5cm 39/1 L60 guns taken from PzKpfw IIIs were to be mounted on makeshift carriages. At the other extreme the German forces built a number of permanent positions. Around the Futa Pass, for example, a number of concrete bunkers to mount anti-tank guns were constructed. On the Adriatic coast near Rimini large coastal emplacements, not dissimilar to those found in the Atlantic Wall, were built. These mounted 15cm guns that had originally been designed for use on ships. Dragon’s teeth were also used extensively around the coast in attempt to deter a further Allied amphibious assault. These were essentially reinforced concrete pyramids poured in rows and designed either to stop an enemy tank completely or to expose the thinner armour of the underside of the tank to the defenders’ anti-tank guns.

On 10 July 1943, the Allies landed on Sicily in what was the largest amphibious assault in Europe up to that point. This was a multinational force under the command of Field Marshal Alexander. Montgomery’s Eighth Army landed on the east coast and experienced little opposition and, as hoped, the naval base of Syracuse was captured on the first day. Patton’s Seventh US Army landed in the south-west of the island where the beaches were more heavily fortified and where resistance was stiffer. Nevertheless, by 12 July the beachhead had been secured and the German and Italian forces were on the defensive.

The Eighth Army made the main thrust of the Allied attack with the Americans securing the flank. But Alexander’s strategy meant that the chance of splitting the island and isolating part of the enemy’s forces in the west was lost. The Axis forces, under the command of General Hans Hube, fell back to the first of their defensive lines, the Etna Line. This held firm against a four-pronged attack by Montgomery and allowed 15. Panzergrenadier-Division to the west to fall back in good order and to dig in around Troina in the knowledge that its line of retreat was secure. Hube’s forces were now ensconced in a line that ran from Acireale to San Fratello. The British continued to press from the south while the Americans pushed east. The 1st (US) Infantry Division fought a fierce five-day battle to dislodge German troops from Troina and further north German positions along the San Fratello proved to be a bloody challenge for the 3rd Division. However, pressure from the Americans and the British eventually forced the German forces to withdraw and plans for a total evacuation were prepared. A series of defensive lines were established further back, each shorter than the last and requiring fewer troops to defend so allowing the rest to be evacuated. The Axis forces surrendered on 17 August, but by that point 40,000 German and 62,000 Italian troops with much of their equipment had been safely transported to the mainland.

A little over a fortnight later the Allies landed on the Italian mainland and, after an initial scare at Salerno, consolidated their hold and advanced north to the so-called Winter Line. The Allies hoped to bounce this position before the enemy had time to settle in. To the north of Monte Cassino the French Expeditionary Corps (FEC) attacked towards Atina. They successfully negotiated the perils of the River Rapido and closed on the outworks of the Gustav Line proper, but with the troops tired and cold from their exertions in the depths of a bitter Italian winter and meeting stiff German resistance the attack was suspended.

A US soldier examines the internal workings of a captured MG-Panzernest. It has been covered in rocks for added protection and camouflage. Just visible in the right foreground is a German mess tin. (NARA)

A destroyed army observation post for a coastal battery (Type 637) that was located on the west coast. In the front section a rangefinder would have been fitted to pinpoint enemy targets for batteries located further to the rear. (NARA)

General Mark Clark, who now commanded American forces in Italy, had argued that attacks be launched on both flanks of the Gustav Line to increase the chances of a breakthrough and on 20 January II (US) Corps began what was hoped would be the decisive thrust across the Rapido and up the Liri Valley. General Fred Walker’s 36th (US) Infantry Division was ordered to lead the attack. Covered by an artillery barrage the Texans advanced to the river with their assault boats and made their way across, but were met with a hail of machine-gun fire. The defenders, men of 15. Panzergrenadier-Division, had sheltered in deep dugouts during the barrage and now emerged to man their weapons in pre-prepared positions, which had been carefully sited to create a belt of interlocking fire.

Having reached the far bank there the Americans enjoyed no respite. Mines and barbed wire blocked their advance and, trapped in their tiny bridgehead with no easy route to retreat, they were subjected to intense mortar, artillery and Nebelwerfer fire that had been pre-registered on both banks. Eventually it was realized that the position was untenable. A few men managed to extricate themselves, but the rest were either killed or captured.

Still reeling from the bloody reverse crossing the Rapido, Clark tried to regain the initiative by launching another attack north of Cassino on the night of 24/25 January. General Charles Ryder’s 34th (US) Infantry Division, supported by the FEC, was to cross the Rapido and, having secured a bridgehead, capture Monte Cassino. The defences in this section of the line were particularly strong and made any advance extremely difficult. The regimental commander of 133rd Infantry Regiment wrote, ‘MG nests in steel and concrete bunkers had to be stormed. Progress was measured by yards and by buildings. Each building had been converted into an enemy strongpoint… Casualties were heavy.’ Not surprisingly the Americans struggled to make any headway, and with no armoured support the attack faltered. A better crossing point was identified and a renewed attack proved more fruitful with tanks able to support the infantry. The signs looked promising and Clark signalled Alexander that Monte Cassino would fall soon, while von Senger und Etterlin, the commander of XIV Panzer Corps, suggested to Kesselring that German forces retire to the Caesar Line.

Victory seemed to be in sight and one more thrust was ordered on 11 February. But this proved to be ill conceived. The Americans had suffered terrible casualties and morale was low. Ryder’s division was simply not capable of delivering the coup de grace. The first battle of Monte Cassino had ended and the Gustav Line had held firm.

A section of German trench that was hewn out of solid rock. The trench formed part of the Gothic Line defences and dominated a hairpin bend in the Apennines. US forces captured it in 1944. (NARA)

An MG-Panzernest that formed part of the Gustav Line defences is removed from where it had been buried. An M32 tank recovery vehicle, more used to towing tanks, is used to transport the nest. (NARA)

The Americans were relieved by elements of 4th Indian Division, who were now tasked with capturing Monastery Hill. Meanwhile 2nd New Zealand Division was ordered to capture Cassino railway station. On 15 February, the operation was launched but both attacks were unsuccessful. However, the second battle for Monte Cassino is most noteworthy for the decision to bomb the abbey atop the hill which the Allies believed was occupied by the German forces. It later transpired that this was not the case, but the German troops were not slow to seize the opportunity and integrate the ruins into their defences.

A massive aerial and artillery bombardment similarly preceded the Third Battle for Monte Cassino, which it was hoped would smash the enemy defences and allow the Indians and New Zealanders to achieve their respective goals. On the morning of 15 March, the bombardment began. The results looked impressive and indeed the defenders in the town and on the surrounding hills suffered terrible losses, but enough survived in deep dugouts and caves hewn into the solid rock to man basement strongpoints and other positions. At the same time the bombardment served to flatten most of the buildings still standing, making navigation difficult and ensuring that it was all but impossible for the armour to support the infantry. Where the tanks did get forward the German soldiers easily picked them off using hand-held anti-tank weapons or mines. The New Zealand infantry did manage to reach Highway 6 and eventually some tanks wormed their way forward and engaged enemy strongpoints. One of these was centred on the Continental Hotel, which dominated the highway. A tank had been built into the entrance hall and it was key in preventing the New Zealanders from pushing armour down the road to Rome. By 23 March both sides were exhausted and the New Zealanders’ attack was called off. Meanwhile, the Indians had captured Castle Hill and Hangman’s Hill, but their hold was not sufficiently strong to act as a springboard for an attack on the monastery and they simply dug in to consolidate their gains. Eighth Army now reorganized and prepared for a new attack in the spring in what it was hoped would be the final breakthrough.

Nebelwerfer position. The Nebelwerfer 42 was often employed in specially prepared positions, as depicted here. This was one of six such emplacements in this section of the Hitler Line and was located 1,000m behind the frontline. The emplacement consisted of a shelter 6 x 3.3 x 2.2m partly cut into the ridge at the rear and partly built up. Behind the shelter was a 2 x 1.3 x 0.5m concrete block, which was embedded so as to project just 15cm above a hardcore floor. Ammunition was stored in niches set into the side of the position. These were stacked in specially designed transport cages. (Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

One of the 15cm naval guns in its concrete emplacement. Four of these positions were constructed in the vicinity of Rimini to protect against a potential amphibious assault. The New Zealanders captured them during their drive along the coast in September 1944. (Imperial War Museum, NA 18992)

The Allies had tried to breach the Gustav Line on three occasions and although success had been tantalizingly close on a number of occasions the German forces held firm. This was partly because of the natural strength of the position with its fast-flowing rivers and mountains that dominated the main routes of advance. In part it was due to poor Allied leadership. The decision to bomb the Monastery gave the defenders an ideal defensive battleground and made combined operations almost impossible for attacking units. Crucially, the great opportunity of outflanking the position with the amphibious assault at Anzio was squandered by overly conservative commanders on the ground whose inaction was summed up by Churchill when he told the Chiefs-of-Staff, ‘We hoped to land a wild cat that would tear out the bowels of the Boche. Instead we have stranded a vast whale with its tail flopping about in the water!’ But the defences undoubtedly played a part in blunting the Allied attacks. The defences provided valuable protection against the Allied air and artillery bombardment and the strongpoints, carefully sited so that they could bring devastating fire to bear on the enemy, proved to be exceptionally difficult to neutralize. Eventually the Gustav Line was breached and the Eighth Army advanced along the Liri Valley, but it was now faced with the prospect of defeating the Hitler Line.

The MG-Panzernest was developed in the second half of the war and was used extensively in Italy. The thick upper armour provided valuable protection for the two-man crew and the nest was easily transported with the opening at the front doubling as the housing for the towing limber and the holes for the ventilation acting as the mounting for an axle, which was then fitted with two wheels. The position was designed to mount a machine gun that could fire through a small aperture at the front. This limited the weapon’s traverse and meant it only had a 60-degree field of fire. When the position was not in use the opening could be covered with a shield. The crew gained access to the position via a hatch at the rear and two periscopes in the roof provided them with observation. When they were firing the machine gun, fumes were extracted by a simple foot-operated ventilation system. The MG-Panzernest was installed in a simple seven-stage process.

1. Firstly, the Panzernest had to be transported to the site. To do this, the nest was turned upside down and was fitted with a limber, axle and wheels.

2. Once the nest arrived at the site the front limber was removed and a hole dug.

3. The nest was now manoeuvred into place. Earth under the turret was dug away so that the wheels could be removed.

4. A rope was now secured to the base of the nest and a lever inserted under the nose. Eight of the crew would pull on the rope and three other men would use the lever to tip the nest into the hole.

5. If the nest was not pointing in the right direction, crowbars could be inserted in the axle holes and ropes attached so that the team could pull the nest round.

6. Once installed spoil would be heaped around the sides.

7. Finally, the equipment was fitted.

(Chris Taylor © Osprey Publishing)

At first light on 19 May a probing attack was launched against the Hitler Line. Two battalions of infantry supported by tanks of 17th/21st Lancers and the Ontario Regiment of Canada advanced towards Aquino. Screened by early morning mist the composite force made good progress, but the fog cleared and an emplaced Panther turret quickly destroyed three US tanks. The tanks of the Ontario Regiment engaged the enemy, but it was an uneven struggle and under the cover of darkness those tanks that could withdraw did so. All of the tanks in the two leading squadrons suffered at least one direct hit and in total the Ontarios lost 13 tanks.

Another probing attack was put in against the defences around Pontecorvo on 22 May by 48th Highlanders of Canada and a squadron of tanks from 142nd Royal Armoured Corps (RAC; the Suffolks). The result was much the same with three of the Suffolks’ tanks knocked out by an emplaced Panther turret. All efforts were now concentrated on the main attack planned for the following day, which was to be made by 1st Canadian Infantry Division supported by 25th Tank Brigade.

A view from one of the many concrete emplacements constructed around the Futa Pass that were captured by 91st (US) Infantry Division. This anti-tank emplacement had a clear field of fire across the tank trap in the middle distance and the road further on. (Imperial War Museum, NA 18929)

The main thrust was to be delivered by two battalions of 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade – the Seaforth Highlanders on the left supported by two squadrons of tanks of the North Irish Horse and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry on the right supported by a single squadron. At the same time the 48th Highlanders were to maintain the pressure on the enemy around Pontecorvo and, on their right, 3rd Infantry Brigade, supported by the 51st Royal Tank Regiment (RTR), was to launch a feint to keep the enemy guessing as to the Allies’ true intentions.

Somewhat unexpectedly these secondary operations enjoyed a certain amount of success with the tanks of the 142nd RAC destroying an emplaced Panther turret protecting Pontecorvo and 51st RTR advancing to the Aquino–Pontecorvo road – the first objective of the main thrust – and in so doing also put a Panther turret out of action. However, the main attack of 2nd Infantry Brigade was not going as well.

The Patricias reached the enemy wire, but their supporting tanks were stopped by an undetected minefield and as they struggled to find a way through four of their number were picked off by enemy anti-tank guns and the remainder fell back to find another way forward. Unaware of their compatriots’ difficulties the Loyal Edmontons, supported by a squadron of 51st RTR, followed the Patricias in accordance with the second phase of the attack. The tanks, however, were similarly balked by mines and a number fell victim to the Panther turrets and their supporting anti-tank guns.

To their left the Seaforth Highlanders and the North Irish Horse made better progress, but when only 100m from their first objective the tanks came under heavy anti-tank fire, which accounted for five of their number including the squadron leader. The remainder beat a hasty retreat and, together with tanks from C squadron that had been held in reserve, advanced on a new axis. This force accounted for another Panther turret, but lost seven tanks in the process.

In spite of the losses the unremitting pressure along the southern portion of the line had forced the enemy to retreat. The attack against Aquino was now resumed to exploit the enemy’s disarray. Men of the Lancashire Fusiliers supported by two troops of tanks of 14th Canadian Armoured Regiment advanced on the town, but soon four of the six tanks had been destroyed and the others retired. Despite being outflanked it was clear that the enemy still held the defences in strength and it was not until the following day that the enemy finally withdrew, having first demolished the two Panther turrets defending the town.

In total 25th Tank Brigade lost 44 tanks (although some were later recovered): the heaviest tank losses inflicted on the Eighth Army in the Italian campaign. An intelligence report written after the battle noted, ‘In front of each position there was a graveyard of Churchills and some Shermans… This is, at present, the price of reducing a Panther turret and it would seem to be an excellent investment for Hitler.’

At the same time as General Oliver Leese’s Eighth Army launched its attack to breach the Hitler Line, Alexander ordered Clark’s Fifth US Army to break out of the Anzio bridgehead. General Lucian Truscott, the commander of VI (US) Corps at Anzio, planned to attack towards Cisterna and then advance to Valmontone with a view to cutting Highway 6, one of Vietinghoff’s (AOK 10) main lines of retreat. This plan was endorsed by Alexander and initially VI (US) Corps made good progress towards its objective. However, on 25 May Clark changed the focus of the attack away from Valmontone towards Rome. This change of tack undoubtedly had a number of military advantages, but it was also fraught with danger because it would involve attacking the strongest section of the Caesar Line, which was held by General Alfred Schlemm’s very strong and highly motivated I Fallschirmjäger Korps (I Parachute Corps), which was more than capable of defeating any such attack.

A flight of steps constructed from logs held in place by wooden pegs. They led to a German position in the Gothic Line. Camouflage nets, that would have prevented Allied planes spotting the position, hang limply at the side. (NARA)

Only 3rd (US) Infantry Division continued its advance towards Valmontone. The Old Ironsides, 1st (US) Armored Division, which had been guarding its left flank, was now ordered to head north as were 34th and 45th (US) Infantry Divisions, which were tasked with capturing Lanuvio and Campoleone respectively. The new operation was launched on 26 May, but almost immediately the attack of 1st (US) Armored Division was stopped dead by mines and well-placed anti-tank guns manned by 4. Fallschirmjäger-Division. The advance of 34th (US) Infantry Division was similarly halted on 27 May and slightly later 45th (US) Infantry Division experienced the same fate. The assault on the Caesar Line was resumed on 29 May with an attack by 1st (US) Armored Division slightly further to the west, but this was also unsuccessful. As soon as the tanks approached the defences they were engaged by anti-tank guns and infantry armed with Panzerfaust hand-held anti-tank weapons. By dusk 37 American tanks had been knocked out, most of them destroyed. A further attempt to breach the line was launched the following day, this time with infantry in the lead, but the result was the same.

General Walker’s 36th (US) Infantry Division had replaced 1st (US) Armored Division in the line after it had initially been withdrawn and it was envisaged that the infantrymen would launch another set-piece attack against the main defences of the Caesar Line. But General Walker, whose men had suffered heavy casualties by adopting such tactics at Salerno and, more recently, crossing the Rapido, was not keen and considered a number of alternatives. One that presented itself was to attack through the Alban Hills rather than going round. The OKW had largely ignored the hills, in part because they lay on the corps boundary, and in part because they were considered unsuitable for an enemy attack. A patrol ordered to reconnoitre enemy dispositions on Monte Artemisio found that it had not been fortified and nor was it occupied. But equally there were no obvious routes to the top save for a narrow farm track. However, engineers were convinced that the track could be widened to take military vehicles and so the decision was taken to attack on 30 May. Two infantry regiments made their way to the top of the mountain under the cover of darkness. They caught the small garrison completely by surprise and captured it without a shot being fired. Engineers soon set to work improving the track and men of Walker’s division dug in on the heights. Through a mixture of complacency and élan the 36th (US) Infantry Division had captured the 1,000m peak. In so doing the Caesar Line had been turned and, on 5 June, Mark Clark was in Rome.

Clark’s decision to attack the strongest portion of the Caesar Line not only allowed the German units to extricate themselves from a possible encirclement, but also meant that he unnecessarily weakened his divisions, which made it difficult for them to pursue the enemy north of Rome. This, together with the panoply of lines and defensive positions that the German forces had established between Rome and the Gothic Line, slowed the Allied advance. The Eternal City fell on 5 June but it was not until the end of August that the Allies were in a position to launch an attack against the last bastion before the Alps.