FOUR

THE AQUEOUS ATMOSPHERE

IN OCTOBER 1876, JUST AS ALARM SPREAD ACROSS MADRAS OVER THE failure of the rains, India’s eastern seaboard was struck by the worst cyclones ever recorded. Two storms followed in rapid succession: the first hit Vishakapatnam on the Orissa coast; the second inundated the Meghna delta in eastern Bengal. The loss of life was incalculable—the greatest toll was taken by the storm surge that accompanied the cyclone as it hit eastern Bengal. The commissioner of Dacca division, surveying the devastation, wrote of one locality that “not a single hut and hardly a post was left standing”; it was, he said, “too soon to attempt to compute with anything like accuracy the loss of life which has occurred.” In district after district, local people estimated that 40 or 50 percent of the local inhabitants had died. In another village on his journey the commissioner listed the victims not by their names but by their positions: “Moonsif, rural sub-registrar, native doctor, post-master, court sub-inspector, abkaree darogah, two abkaree burkundauzes, seven constables, a mohurir of the moonsif’s court, and a post-office peon.”1

John Eliot, meteorologist of Bengal, set out to archive the storm. He relied on the usual combination of ships’ logs and eyewitness accounts, supplemented now by records from the many land-based observatories that had been established over the preceding decade. Eliot conveyed the ferocity of the storm as it built over the Bay of Bengal: “This piled-up mass of water advanced under the pressure of the acting forces towards the head of the Bay” at twenty miles an hour. He estimated that the storm contained latent energy from the evaporation of water over the Bay of Bengal “equal to the continuous working power of 800,000 steam-engines of 1,000 horse-power.”2 Eliot proceeded to narrate an epic battle of forces between the storm wave rushing in from the ocean, and the Himalayan rivers—the combined power of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra—seeking an outlet to the sea. “These two vast and accumulating masses of water opposed each other over the shallows of the estuary,” he wrote; their “struggle and contention for mastery” brought death and destruction to millions of people. Eventually, the “larger and more powerful mass of water forming the storm-wave” overcame the river waters. It deluged the islands at the mouth of the Meghna, one of three rivers that constitutes the Ganges delta; the islands were themselves “formed chiefly from the detritus of the Himalayas deposited over the area in which the tidal and river waters wage incessant warfare.”3

This was a vision of India’s climate shaped by water in every dimension: the descent of water from the Himalayan rivers and the ascent of water vapor from the Bay of Bengal and the winds stirring the ocean surface and transporting clouds to shore. On what scale should the climate of India be understood? The problem, Eliot noted, was that “so little is known of the action and independent motion of the aqueous vapour in the atmosphere, and of its relations to the atmosphere of dry air.”4 Tracking alongside the story of the disastrous famines, this chapter charts the quest to understand the monsoon that unfolded in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Famine spurred the development of Indian meteorology. As knowledge of the monsoons grew, so, too, did awareness that India’s climate was shaped by distant influences. As India’s boundaries hardened, it mattered more to understand the rivers that crossed them. New knowledge of water raised new questions about India’s place in Asia—and uncomfortable questions about how far science could conquer nature.

I

Meteorology was an international science by the 1870s: the telegraph had allowed the world’s weather to be tracked with unprecedented immediacy. In 1873, the United States and a number of European countries agreed to form the International Meteorological Organisation (IMO). Like many international associations at the time, the IMO was a voluntary initiative, founded on an aspiration for greater cooperation between national weather services in the sharing of information. Like many international associations at the time, its concerns were dominated by those of industrialized, imperial powers. Britain claimed predominance in international meteorology because it represented a vast empire of climatic variation.5

Among the priorities of the new international meteorology was to devise a common and standardized language in which to describe the weather anywhere in the world. Especially daunting was the challenge of finding words to describe clouds in all of their variety, in their mutability and evanescence, in all of their profoundly local manifestations. The tools of Linnaean classification struggled to capture the texture of the skies. The basic cloud types that we still use—the puffy white cumulus; the gray blanket of stratus; the wispy cirrus; the dark rain cloud, nimbus—date from the early nineteenth century, in the parallel but independent work of Luke Howard in England and of the French statistician Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. The midcentury advent of photography was a fillip to cloud watchers, giving them the tool to capture clouds in a fleeting instant. Under the leadership of Swedish meteorologist Hugo Hildebrandsson, director of the Uppsala observatory, the IMO published its first international cloud atlas in 1892. The atlas aimed to standardize the cloud observations that professional and amateur meteorologists and cloud-watchers were compiling the world over. Hildebrandsson and colleagues illustrated their atlas primarily with photographs, each illustrating a typical instance of a particular cloud form, even if each individual cloud that had been photographed would have changed shape moments later. As historian of science Lorraine Daston observes, long after the effort to standardize observations, knowledge of clouds and weather remained a profoundly local affair.6

Meteorologists in the nineteenth century studied the genesis of storm systems in the Indian Ocean. CREDIT: Illustration by Matilde Grimaldi

Formal classification could not always capture the nuance of clouds in different climates. In agrarian societies (and so across much of Asia) the mutability of clouds had an immediate bearing on people’s fortunes and the sky was a series of signs to be read, or warnings to be heeded. Every Indian language contains a rich lexicon to describe clouds, capturing their relation to the seasons and to the landscape. In Tamil, mazhaichaaral invokes the drizzle from clouds that gather atop hills; aadi karu are the dark clouds that gather in the month of aadi, promising a good harvest to come. Notwithstanding the promise of meteorological advances, British officials in India often turned to local, or what they called “folk” knowledge, when they wanted to understand how the weather shaped the harvest. Historian Shahid Amin found in the local archive of Gorakhpur district, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, a handwritten account from 1870, penned by a British district officer, compiling local aphorisms about the seasons. The sayings take the form of instructions to farmers issued by each season, personified by its name in the Sanskrit calendar. The hot summer season of “Jeth” (in May and June) says: “Be undaunted by the heat of the season. Make ready your threshing flood; work hard and gather the produce before the rains set in.” The winter season of “Magh” warns farmers to “leave your cane mill and drive the water full into your fields. If God be pleased to give you rain you will be truly blessed.” Other regional traditions across India had their own stores of wisdom about the clouds and the rains. In the words of a Tamil proverb, “If clouds withhold their gifts and grant no rain, the treasures fail across the ocean’s wide domain”—local wisdom conveyed an awareness of the connectedness of the weather across large areas. Cultivators searched the skies for signs of foreboding. “Oh farmer!” another proverb pleads, “get out of the field with the young seedlings in your hand, should you see the first crescent moon in [the month of] Arpisi.” Right up to the 1930s, alongside the development of meteorology, local governments in British India collected and published proverbs about climate and weather and cultivation.7

But the monsoon failures of the 1870s were so total, so devastating, that new answers were sought from the new science of climate.

II

Faced with the total failure of the rains in 1876 and 1877, India’s meteorologists sought an explanation. Leading the quest was Henry Blanford, the geologist-turned-meteorologist who had risen to prominence with his study of the Calcutta cyclone of 1864, and who was now director of the Indian Meteorological Office. In his regular report on India’s climate and rainfall for the year 1876—written with factual detachment in the midst of disaster—Blanford ascribed the drought to the “remarkable and unseasonable persistence of dry northwest winds”—winds he had studied a few years earlier.8 Blanford observed two abnormal forces at work: the first was exceptionally high pressure across northern and western India; the second was a sharper than normal temperature contrast between northwestern and eastern India. He concluded that “some cooling influence more potent than usual was at work, probably in the Punjab and on the northern mountain zone.”9 The following year, again, Blanford reported that “the land winds have been so persistent in the upper provinces and on the plateau south of the Ganges, as to cause an almost complete failure of the summer rains in that region.”10 As he sought to understand what had happened, what Blanford needed above all was data.

By the time of the famine commission report in 1880, India had more than one hundred meteorological observation centers. In the decade that followed, Madras, for instance, maintained eighteen observatories under the directorship of Elizabeth Isis Pogson. She was the daughter of Norman Pogson, an astronomer who was director of the Madras Observatory for decades. Isis was taken on in 1873 in the role of “computer,” earning the salary of a “cook or a coachman.” The family grew up in poverty, and Isis was forced to work, as well as looking after her siblings upon her mother’s death. By the 1880s, as meteorology developed as a branch of science separate from astronomy, she was placed in charge of Madras’s network of monitoring stations.

Pogson was zealous, inspecting regularly as many of the rain monitoring stations as she could. Her reports exposed the shaky edifice upon which India’s weather data were based. Weather observatories tended to be built on hospital grounds, under the responsibility of the local medical officer; some were more enthusiastic than others about this addition to their duties. At Cochin, Pogson found that the local station needed better fencing, “to prevent stray cattle straying into the shed”; she personally arranged for supplies from Oakes and Company of Madras. She battled vandals as much as cattle. In Cuddapah, “the grass minimum thermometer had only been in use for six days when it was… found broken outside the hospital compound, evidently done out of sheer mischief.” From Kurnool, she had to report that the data were “perfectly useless” because of the positioning of the apparatus. There, the local postmaster had to double as the meteorological assistant, and he struggled with the job. “He was very willing and anxious to learn,” Pogson wrote, “but… could not possibly undertake to record” the data “as his combined duties as Postal and Telegraph Master were too much.”11

The traces she has left in the archive are filtered through the technical language of meteorology and contained within columns and tables of official forms. As far as I know she left no personal papers—we can only speculate about how Isis Pogson experienced being a rare woman within the scientific apparatus of British India. As a young science struggling for legitimacy meteorology was likely more open, a little freer from prevailing hierarchies, than more established fields. Meteorology was among the “field sciences” that, as historian Kapil Raj shows, were more open to local knowledge than the laboratory sciences. But the obstacles Pogson faced getting her due recognition as a pioneer of global meteorology are telling. In 1886, she was nominated for membership of the Royal Astronomical Society; she was turned down after the council decided that the use of the masculine pronoun throughout the Society’s charter meant that women could not be admitted as fellows. She finally became a member only in 1920, after she had returned to England, leaving India and meteorology behind.12

The Indian staff of the meteorological department, too, found a degree of openness they would not have encountered elsewhere in the bureaucracy of the Raj, though this was always weighed down by the knowledge that they could never rise beyond a subordinate position. Much was left in their hands by an institution that was young, understaffed, and underfunded. The most senior Indian meteorologist under Blanford, Lala Ruchi Ram Sahni, wrote a memoir in the 1930s, by which time he had risen to prominence as a patriot and a social reformer in Punjab; his recollections give us a rare insight into everyday life in the cockpit of monsoon science. Ruchi Ram recalled the global reach of Indian meteorology even at that early stage; Blanford would invite him home regularly to sit down and discuss the latest research findings “made in Russia, America, or somewhere else.” Blanford’s emphasis was always “on the interdependence of the weather in different parts of the world.” Ruchi Ram recalled that this “made a deep impression on me in its widest implications.”

But Ruchi Ram concluded his account of the meteorological department on a more personal note. He suggested that “if all Englishmen were like Mr Blanford, the social and political relations between the two races [British and Indian]… would have been quite different from what, unfortunately, we find today.” He absolved Blanford of any sense of racial arrogance. Ruchi Ram’s most powerful memory was “trifling,” but revealing. Most British officials in those days, he recalled, would bark orders at their subordinates, keeping them waiting, and standing—but not Blanford. Blanford, Ruchi Ram wrote, “never once shouted to me from his chair, or even sent for me through the chaprasi.” Instead, “the old man would get up from his seat, and opening the door that separated our rooms, would say gently, ‘Lala Ruchi Ram.’”13

Looking forward, it is surprising to note how many Indian intellectuals spent time working in the meteorological department in the early twentieth century. They included Chintamani Ghosh, founder of the influential nationalist periodical The Modern Review, and Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, a master statistician who would play a leading role in making economic policy in independent India. In part, this may have been down to the way meteorology posed a daunting challenge of statistical analysis, which attracted many of India’s brightest minds; in part, it may have come from a sense that understanding the monsoon was of vital importance to India’s future. And perhaps the Meteorological Department also left them freer from restrictions and pressures. On that count, Ruchi Ram learned one important lesson from Blanford: “He would ask me not to do this or that work myself, but got it done by one of the clerks so as to find [me] more time for self-study.”14 But that is to get ahead of the story.

AS RECORDS OF THE MONSOON ACCUMULATED, METEOROLOGISTS looked to capture its “normal” characteristics. In the late 1870s, Henry Blanford described the monsoon as a self-contained system; a climatological force that shaped and demarcated the Indian subcontinent: “India, together with the circumadjacent seas, is, in the main, a secluded and independent area of atmospheric action.”15 In Blanford’s vision, the monsoons were an active force—he saw that “the goal of the monsoon, the place of low barometer to which its course is directed, is constantly changing.”16 Blanford viewed the monsoon as driven by the “primary contrast of land and water.” He confirmed what was by then well known, that the driving force of the monsoon was the difference in solar heat received by the land surface of India at different points in the year, and its contrast with the relative heating or cooling of the Indian Ocean. But Blanford was able, now, to introduce new complexities to the science of the monsoon. He showed that the monsoon was not, as many had believed, “one current flowing alternately to and from Central Asia,” but rather that it was formed from the intersection of “several currents, each having its own land centre.” He described an alternate opening and closing of the Indian subcontinent to wider atmospheric forces. In the periods of transition, as the winds reversed—between March and May, and again in October and November—Blanford observed that “the interchange of air currents between land and sea is, in a great measure, restricted to India and its two seas.” But once the southwest and northeast monsoons had set in, they connected the Indian “wind system,” as Blanford called it, with “those of the Sunda Islands and Australia, and, at one season, the trade winds of the South Indian Ocean.”17

Driven by clear laws, Blanford believed that the monsoons were strongly predictable. “Order and regularity are as prominent characteristics of our atmospheric phenomena,” he wrote, “as are apparent caprice and uncertainty those of their European counterparts.”18 Beneath this broad predictability, however, the monsoon was characterized by its unevenness. Within any given monsoon season, Blanford observed, rains were not “persistent and unvarying”; rainfall was subject to “prolonged periods of suspension” as well as “regular interruptions known as ‘breaks.’” Even more striking was the monsoon’s spatial unevenness: meteorologists found “a great diversity of rainfall” in different parts of India. “No country in the world,” Blanford insisted, “furnishes such contrasts.” Even as the broad contours of the monsoon seemed amenable to prediction, uncertainty was a defining climatic feature in many parts of the country, and “those provinces which have the lowest rainfall are also those in which it is most precarious.”19

Meteorological anxiety about the unevenness of India’s rainfall shaped perceptions of the land itself. In the most lyrical passage in his guide to India’s weather, Blanford contrasted tropical with temperate landscapes:

Instead of feeding perennial springs, and nourishing an absorbent cushion of green herbage, the greater part flows off the surface and fills the dry beds of drains and watercourses with temporary torrents. In uncultivated tracts, where jungle fires have destroyed the withered grass and bushy undergrowth, and have laid bare the soil and hardened its surface, this action is greatly enhanced;… not only is water lost for any useful purpose, but by producing floods, becomes an agent of destruction. Under any circumstances, the character of the rainfall is hardly compatible with economical storage and expenditure in any high degree; and much more, therefore, than in temperate regions is it incumbent on us to safeguard such provident arrangements as nature has furnished for the purpose.20

The rhythms governing the distribution of rainfall proved an enduring mystery. Indian meteorologists pored over the correlations of monsoon failure across different parts of the country. Blanford observed the “curious relations in the way in which certain provinces are prone to vary alike,” suffering drought or excessive rainfall simultaneously, “while others vary in the opposite direction.”21 The 1880 famine commission observed that on five occasions over a century, severe droughts on the Indian Peninsula were followed, a year later, by drought on the plains of North India. The causal mechanisms at work eluded meteorology until well into the twentieth century. Much uncertainty still remains.

As clues mounted, Blanford looked back at his annual reports for 1876 and 1877, and he grasped the significance of two tentative observations he had made at the time. The first was that the years of the great drought had also seen unusually heavy snowfall over the Himalayas, later than usual in the winter. Blanford investigated this puzzle over the years that followed. By 1884, he was convinced that the “extent and thickness of the Himalayan snows exercise a great and prolonged influence on the climatic conditions and weather of the plains of North-Western India.” He suggested that keeping a close watch on Himalayan snowfall might hold the key to predicting the strength of the summer’s monsoon to follow. But he was also quick to acknowledge that the forces at work might be far larger. Between 1876 and 1878, he wrote, “excessive pressure was shown to affect so extensive a region, that it would be unreasonable to attribute it to the condition of any tract so limited as a portion of the Himalayan chain,” vast though the mountains were. Blanford’s calculations showed that high pressure had prevailed across “extra-tropical Asia… and in Australia.”22

Weather scientists across the British empire sought to pool their expertise and their information. Isis Pogson’s detailed account of her library’s holdings in Madras gives us a glimpse of these global connections. It included the proceedings of the First International Meteorological Congress in Vienna and reports from observatories in Batavia and Singapore and Manila.23 The development of monsoon science probably owed more to imperial and interimperial networks within Asia and Oceania than to wider international ones. As Blanford pursued his intuition about the great drought, he relied heavily on “private correspondence” with district officials in the Himalayas, and with meteorologists across the British Empire.24 He wrote to his counterparts at other stations across the Indian and Pacific oceans asking them to furnish him with data on atmospheric pressure from 1876 to 1878. Charles Todd, chief meteorologist of South Australia, was quick to respond with records from South Australia and the Northern Territories. Todd and Blanford both saw that their data correlated. By 1888, Todd concluded that “there can be little or no doubt that severe droughts occur as a rule simultaneously” over India and Australia. Information filtered in to Blanford from island observatories, too, which had long been central to British and French ecological investigations: Mauritius, Reunion, the Seychelles, and Ceylon.25 It was clear, by the 1880s, that the scale of influences on India’s climate reached far beyond India’s shores.

The famine commission of 1880 had expressed hope that the development of meteorology may provide some advance warning of monsoon failure. In 1881, Blanford was asked to come up with concrete proposals to implement the famine commission’s recommendations for the development of India’s meteorological infrastructure. His priority was the establishment of more monitoring stations. But he also looked to the more systematic collection of data from ships: a strengthening of the earliest maritime roots of meteorology. Information from ships was “urgently required” not only to track storms, but also “to throw light on the causes of the variations of the south-west monsoon rainfall.” From 1881, data was collected systematically from every ship entering the port of Calcutta.26

In 1882, Blanford began to produce his first, tentative monsoon forecasts. A long-range monsoon forecast was a fundamentally different enterprise from the storm warnings that had dominated the concerns of Indian meteorologists. Especially with the aid of the telegraph, the approach of storms was now immediately visible. Cyclones were dramatic; their impact was urgent. Forecasting a year’s monsoon, by contrast, required a more fundamental understanding of climate and climatic variation, founded on the slow analysis of a wide range of parameters on longer timescales. Despite his own awareness that India’s climate was subject to oceanic or even planetary influences—a phenomenon that we now know as “teleconnection”—Blanford chose to base his forecasts on one primary indicator: snowfall in the Himalayas. From 1885, the Indian Meteorological Office’s annual monsoon forecasts were published in the Gazette of India—and for the first few years, they proved accurate, at least as a broad-brush indication of whether monsoon rainfall was likely to be normal, excessive, or deficient.

III

The investigation of the oceanic and planetary influences on India’s climate became an enduring concern for John Eliot (1839–1908), Henry Blanford’s successor as director of the Indian Meteorological Office. The son of a schoolmaster and a graduate of Cambridge, Eliot began his career in India lecturing at the engineering college in Roorkee, which Proby Cautley had established at the head of the Ganges Canal; he moved on to Muir College in Allahabad, where he also served as director of the local meteorological observatory. In 1874, he took up a position as professor of physical science at Presidency College, Calcutta, where Blanford had also taught—and Eliot took over Blanford’s role as meteorological reporter to the government of Bengal. In 1886, Eliot again succeeded Blanford, now as the meteorological reporter to the government of India—effectively the head of India’s meteorological service—and held that position until 1903. Tall and heavy-set and prone to bouts of illness, Eliot was also an “accomplished musician” on the piano and organ.27 In contrast with Blanford, Eliot was known, by his Bengali staff, as “the native hater.” Blanford’s most senior Indian officer, Lala Ruchi Ram Sahni, decided he would rather quit his job and move to the Punjab Education Department than work for the irascible and prejudiced Eliot.28

Like Blanford, Eliot first served in Bengal. Like Blanford, his early work was on the cyclones that threatened the Indian coast. Even as prolonged drought stalked the land, sudden tropical storms continued to pose a recurrent threat, as Eliot had seen during the cyclones of 1876. Eliot pursued simultaneously the two strands of Indian meteorology that Blanford handed on to him: the study of extreme weather events, and the quest to forecast each year’s monsoon. The first proved easier than the second to achieve.

Eliot’s greatest influence on the field came from his understanding of cyclones. A few years after taking over as chief meteorologist of British India, Eliot published his Handbook of Cyclonic Storms in the Bay of Bengal.29 The nautical roots of monsoon science remained evident: Eliot’s book was, above all, a practical guide for seafarers. It gained readers across Asia. Among those who learned from Eliot’s book—calling it both “masterful” and instructive”—was Father José Algué (1856–1930), a Spanish Jesuit meteorologist who led the Manila Observatory and stayed on after the 1898 American conquest of the Philippines to head the weather bureau.30 From a network of observatories across the western Pacific, local weather watchers grappled with the power and the unpredictability of tropical storms known as “typhoons” in the Chinese-speaking world: storms identical in nature to the cyclones of the Indian Ocean and the hurricanes of the Atlantic. The Japanese government invested in a centralized system of weather observation in keeping with its modernizing thrust after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Elsewhere private bodies took the initiative—particularly the Jesuits, who founded a series of meteorological observatories across and beyond the Spanish empire: at the Real Colegio de Belém in Havana (in 1857), at Ateneo Municipal de Manila (in 1865), and at Zikawei (Xujiahui) on the outskirts of Shanghai (in 1872). From 1869, the British-run Chinese Maritime Customs Service developed a network of meteorological observation. As in India, the practical value of storm forecasts for mariners provided the spark. Robert Hart, director of the Chinese customs, wrote of his hope of “throwing light on natural laws and… bringing within the reach of scientific men facts and figures from a quarter of the globe which, rich in phenomena, has heretofore yielded so few data for systematic generalisation.”31 These observatories exchanged information and developed a network of observation across the Pacific coast of Asia; but this remained walled off from the Indian Ocean, even as data began to reveal the connectedness of Asia’s climate across its whole expanse. Algué was a towering figure, and he found much in Eliot’s work on the Bay of Bengal to echo his own studies on the Philippine archipelago.32

In his 1904 treatise on The Cyclones of the Far East, a revised English version of a Spanish text written in 1897 (penned under the “roar of the cannon and the rumors of war” that “rob the mind of the calmness which is so necessary in a work of this kind”), Algué insisted that “there is no tropical storm which is developed or felt in the sea or on the coasts of China which has not exercised some influence upon this Archipelago.” The Manila Observatory built weather monitoring stations across the Philippines, staffed by Filipino volunteers and a growing cadre of trained local technicians. Algué aimed to educate the public about the tropical storms that posed a recurrent threat to their lives and livelihoods. But just like Blanford and Eliot in India, Algué imagined a broader climatic region. The telegraph allowed for the transmission of instantaneous weather information. The Manila Observatory could now warn the China coast of approaching storms; meteorologists could “watch” storms developing in the Pacific. A French journalist wrote admiringly of the “completeness with which the Asiatic continent, from Cape St. James to the mouth of the Amur river, is safeguarded against surprises thanks to the meteorological services of Japan and the Philippines.”33 “Owing to the opening up of the Far East in recent years,” Algué wrote, he had revised his work on the Philippines to give it “a greater compass.”34 That “compass” reached beyond the South China Sea and toward the Bay of Bengal.

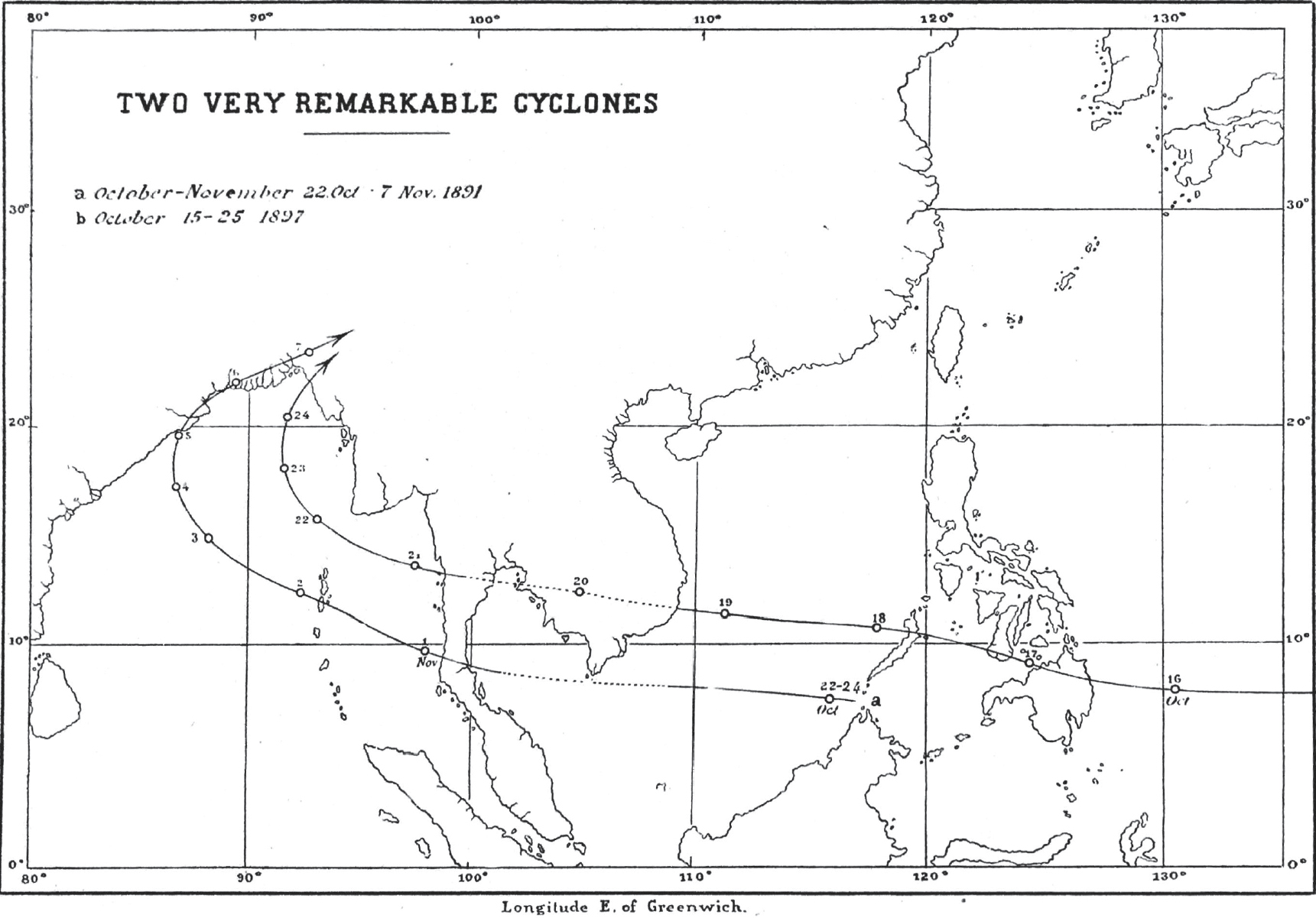

Part of Algué’s book was devoted to an account of “two very remarkable storms” described by Eliot. In a feat of meteorological detection, Algué matched up Eliot’s accounts of the Port Blair cyclone that hit the Andaman Islands in November 1891, and the Chittagong cyclone of October 1897, with his own records in Manila. Of the storm of 1891, Eliot had simply written that there was an “absence of information” on the cyclone’s origins in the South China Sea. Algué found a small item in the Bulletin of the Manila Observatory for October 1891 that might provide the missing context: “Very probably the typhoon which was felt on the 30th and 31st in Singora and other cities,” Manila’s meteorologists wrote, “then traversed the Peninsula of Malaca after running through the Gulf of Siam, to obtain new strength in the Bay of Bengal.” Ships’ logs allowed observers in the Philippines to track the path of the storm down the South China Sea, until they lost sight of it in the Gulf of Siam—which is precisely where Eliot began his account. Eliot picked up the storm in Siam, where on November 1, 1891, a storm wave flooded Chaiya, and “387 religious buildings and 4,238 other buildings were more or less completely destroyed.” It moved out over the Andaman Sea causing devastation in Port Blair, and fizzled out over the east coast of India.

Algué reconstructed the Chittagong cyclone of 1897 with equal precision. There, too, Eliot began his account of the storm on the Malay Peninsula, but Algué traced it back to the seas around the Philippine archipelago. He combed through accounts from Jesuit observers in the Philippines; he tracked the storm’s path through the logs of the German steamer Sachsen, heading from Singapore to Hong Kong, and the British ship Faichiow, traveling from Bangkok to Hong Kong.35

Algué’s account reveals how little communication there was at the time between weather observatories in the South China Sea and those in the Indian Ocean. Each body of water seemed a closed system, each with its own characteristic storms—the typhoon seas and the cyclone seas. The expansion of telegraphic communication allowed for a new sense of scale to emerge, a new way of envisaging weather in time and space. Algué’s map of the two “remarkable storms” presents a different Asia: an Asia of storm tracks that traversed sea and land, crossing imperial borders; a coastal rim from the Philippines in the east to India in the west that shared risks to an extent previously unimagined.

“Two Remarkable Cyclones”: a map from Algué’s study of typhoons and cyclones. CREDIT: Rev. José Algué, The Cyclones of the Far East (Manila: Bureau of Public Printing, 1904)

But where Eliot succeeded in illuminating the nature and the threat of cyclones, his long-range forecasts of the South Asian monsoon fared less well. The number of weather monitoring stations in India grew from 135 in 1887 to 230 in 1901. By the turn of the twentieth century, the meteorological office issued five daily weather reports—one for India as a whole, and one for each major region (including one for the Bay of Bengal). Eliot’s most significant innovation was to introduce what he called an “extra-Indian” dimension to his forecasts. He incorporated into his forecasts data from the southern Indian Ocean; he was particularly convinced of a correlation between pressure in Mauritius and monsoon rainfall in India. Eliot’s forecasts grew increasingly elaborate through the 1890s as they “extended to thirty printed foolscap pages.”36

However, Eliot’s forecasts failed to warn of the climatic disasters that arrived in India in 1896–1897, and again in 1899–1900. Both, later research would show, were strong El Niño years; both droughts reached beyond India to affect China, Southeast Asia, and Australia. In 1899, Eliot’s forecast predicted that monsoon rainfall would be “on the average of the whole area… slightly above the normal.” As it proved that year the shortfall from “the normal” was worse than ever before. But even had Eliot predicted the drought accurately, it is unlikely that the British colonial government would have had the willingness or the drive to intervene on the scale that would have been necessary to avert starvation.

IV

What did it imply to think of Asia as an integrated climatic system? According to the evolving understanding of storms and monsoons, Asia appeared as an expanse of depth and altitude put in motion by the circulation of air. It was a land- and seascape defined by nature rather than by empires, its boundaries dictated by the winds and the mountains. But as soon as this picture of climate was translated into two-dimensional maps, the weight of political boundaries became evident. The first Climatological Atlas of India, compiled by John Eliot after his retirement from India, began with a map of winds and pressure across an interlinked oceanic and continental system. It showed how the climate of India was shaped by the transfer of heat and energy between the Eurasian continent and the vastness of the Indian Ocean. This was in keeping with Eliot’s own, evolving understanding of India’s monsoon. But the flurry of maps in the atlas—monthly maps of temperature and humidity and rainfall, cloud cover and wind direction and wind speed—confined themselves to the territorial expanse of British India. In map after map, the territory of British India was shaded a different color from the surrounding mass in order to stand out; even the arrows showing wind speed are limited to the subcontinent, as though the winds were self-contained. Only the map of storm tracks stretches out toward the Bay of Bengal, as if the ocean were but an external source of weather as it affects the land.37

Climate science was forced into contact with geopolitics. Ideas about India’s climate echoed, and informed, broader debates about India’s place in the world. The networks of storm warnings along the coastal crescent from India to China mirrored Asia’s maritime geography. The names of the stations that broadcast telegraph reports were the names of the great ports; the tracks of the tropical cyclones they monitored were the tracks of busy shipping lanes. Research on the longer-term regularities of India’s climate, as opposed to episodic weather, pointed in a different direction. India’s climatology emphasized its distinctiveness, even its isolation. As Blanford put it, the monsoon system rendered India “a secluded and independent area of atmospheric action.” Ideas about climate coincided with new understandings of both geology and geopolitics. Blanford had begun life as a geologist, and in the late nineteenth century others in that field delved deeper into India’s natural history. They argued that India was a breakaway fragment of the lost supercontinent of Gondwana that had collided with Eurasia in what was, on a geological timescale, the recent past. In the realm of geopolitics, at the same time, British strategists were increasingly worried by threats to their dominance that came not from sea, but from land, through the mountains of Central Asia—the threat from Russia above all. These arguments about India—each of them depicted visually in the form of maps—came together to produce a “subcontinental” as opposed to what had been essentially a maritime view of India. The use of the term “the Indian subcontinent” dates from the early twentieth century. The Himalayas were crucial to this vision of India. They came more clearly into view in the last two decades of the nineteenth century: their role in India’s climate, their place as the source of India’s rivers, their strategic importance to India’s security.

The official compendium of India’s history and geography, the Imperial Gazetteer—edited by William Wilson Hunter, a keen meteorologist as well as an ethnographer, and published in eight volumes in 1881—insisted that “by India we now imply not merely the wide continent which stretches southward from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, but also the vast entourage of mountainous plateaux and lofty ranges.” India, Hunter insisted, “can no longer be considered apart from that wide hinterland of uplands.” This was a political as much as a geographical imperative. “India,” he wrote, “must be held to include those outlying territories over which the Indian administration extends its control, even to the eastern and southern limits of Persia, Russia, Tibet, and China.” It was overland, across the mountain passes from the northwest, that every invading force—save the British—had arrived in India. India’s imperial rulers continued to fear a resurgent threat from their rivals among landed Eurasian empires. But Hunter’s concern was with the future as much as with a repetition of the past. In “a future of railways developments,” with a “rush of motor traffic,” it was possible that “the land approaches to India” would “rival those of the sea”—“then will some of these again become the highways of the eastern world.” By that time, “we shall take out tickets in London for Herat, and change at Kandahar for Kabul or Karachi.” Among these frontiers, the least explored but one “potentially destined to play an important part in Indian history” was “the great highway of the Brahmaputra valley from the plateau of Tibet to the plains of Assam.”38

Hunter drew two conclusions. The first was that “the material wealth of India largely depends” on its “capacity for the storage of that water supply which carried fertility to its broad plains.” The other was that British India’s security depended on “guarding the gateways and portals of the hills,” preventing “those landward irruptions” that had reshaped Indian history on many occasions in the past. These propositions would endure; they would outlast the British Empire that Hunter and his contemporaries wanted above all to preserve. And here is the contradiction at their heart: envisioning India through its rivers encouraged a far-reaching consideration of its connections with distant places, of “world highways” (or potential “highways”) that situated India in relation to the flow of goods, people, money, and water to and from China, Tibet, and the expanse of Central Asia. By contrast, to see the Himalayas as a natural barrier, one always under threat of breach, was to advocate for a vision of India as a bounded place, an “amphitheater” sealed off from the rest of Asia. Natural frontiers became synonymous with the security of the realm. Hunter’s concern with the economic value of water to Indian agriculture reinforced this bounded view. Water was a resource to be stored, possessed, harnessed, and put to work: the essence of India’s “material wealth.”

Hunter’s was a view moving up to the mountains, and away from the ocean. The last part of the nineteenth century saw a final push of Himalayan exploration, which had begun a century earlier. When Trelawney Saunders drew his map of India’s mountains and river basins in 1870, he noted that Tibet was still terra incognita; Arthur Cotton argued the same when he dreamed of a canal link between India and China. Locating the source of Asia’s great rivers was the final frontier in the spate of expeditions undertaken by European explorers in the nineteenth century. It was not until his expedition of 1905–1908 that the Swede Sven Hedin finally discovered the source of both the Indus and the Brahmaputra on the Tibetan Plateau. Describing his first sight of the Brahmaputra, Hedin fell into rapture. “Above the dark-grey ridge rises a world of mountains which seems to belong to the heavens rather than the earth,” he wrote of the northern Himalayas, “between them and the dark grey crest, comparatively near to us, yawns an abyss, a huge fissure on the earth’s crust, the valley of the Brahmaputra or the Tsangpo.” He described the water: “Bluish-green and almost perfectly transparent, it flows slowly and noiselessly in a single bed to the east, while here and there fishes are seen rising.”39

A decade after Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous address to the American Historical Association, on the “closing” of the American frontier, the British imperial geographer and strategist Halford Mackinder made the point on a much larger scale. In 1904, just the year before Hedin’s expedition, Mackinder argued that “geographical exploration is nearly over.” There were no “blank spaces” left on the map of the world. In Asia, he witnessed “the last moves of the game first played by the horsemen of Yermak the Cossack and the Shipmen of Vasco da Gama.” Mackinder foresaw that the heartland of Eurasia would, again, become the pivot of global power. “A generation ago steam and the Suez Canal appeared to have increased the mobility of sea-power relatively to land-power,” he declared, but now transcontinental railways were “transmuting the conditions of land-power.”40 In this light the mountainous frontier of the Himalayas still appeared remote and forbidding. But it was now clear that they might contain vast water resources—resources to be captured for the development and security of the plains.

And here we have the paradox that deepened in these years: water and climate were boundless. Their boundlessness became clearer with every advance in the technologies of measurement. Yet, as the next chapter will show, they came under ever tighter but more fragmented territorial control. We turn now to the fevered quest for water that gripped India, and most of Asia, in the early decades of the twentieth century.