CHAPTER FOUR

BATTLE

IN HIS REPORT TO THE COMMITTEE OF SAFETY on April 1, 1776, Henry Fisher noted Hamond's chase of the Lexington: “The Brig [with] Capt. Barry came down under Cape May Around on Sunday Morning went out—the Ship and Tenders put out to Sea after the Brig but returned on Sunday evening into the road.”1 Although anxious to see action, Barry knew the Lexington was no match for one of His Majesty's frigates. He proceeded up the New Jersey coastline.

After two days without so much as sighting a sail, he reversed course above Barnegat Bay, and came down to Little Egg Harbor. Once ashore he learned that the tender for the HMS Phoenix had captured three prizes and sent a landing party ashore. The British tars terrorized a family in their home on the Absecon beach, taking “even the clothes on the children's back[s].”2 Deducing that the tender and her prizes had already reached New York, Barry returned to the Lexington and headed south for Virginia.3

On April 4, the Lexington's mast-header sighted a sail on the horizon. The brigantine gave chase and quickly overtook a sloop from St. Croix.4 Despite the protests of the captain that he was on an innocent mission to New York, Barry turned the sloop over to a lieutenant and a small detachment of the Lexington's crew, with orders to sail to Philadelphia.5 The Lexington accompanied the sloop to Cape May, where Barry received a signal from Fisher.

That evening, the resourceful pilot was rowed out to the brigantine and delivered a letter to Barry from Nathaniel Falconer: a small fleet of merchant ships under the Cape was in need of escort. The next day, with overcast weather acting as a perfect shield, Barry convoyed them past the usually watchful Roebuck on April 5. Once the merchantmen cleared Cape May, they headed northward. Barry continued his southerly course.6

Hamond, meanwhile, received word regarding Esek Hopkins: the “Philadelphia Squadron having been at [New] Providence & St. Augustine . . . were certainly on their return to Philadelphia. . . . Upon receipt of this Intelligence I took care to place my Ship in the best Manner I could to intercept them.”7 Hopkins's fleet, which Hamond's report listed as seven ships, was much more appealing prey than Barry's small ship, as far as the intrepid captain of the Roebuck was concerned. His change in plans and direction allowed Barry to slip past the Capes undetected. By Sunday morning, April 7, the Lexington reached Cape Charles, Virginia, the home waters of Lord Dunmore's fleet of “Royal Pirates,” just a short distance from the charred remains of Norfolk. There would certainly be a chance for action there.

That afternoon, the Lexington's lookout spotted a sail coming from the southwest. Believing her to be a sloop of war, Barry ordered, “Beat to quarters!” Still keeping the Lexington's gun ports closed, and not flying the “Grand Union,” he gave orders to head eastward, giving the impression that the Americans were trying to escape.8 With his bait set, the sloop took up the chase, and soon began to overtake the Lexington. Barry's suspicions that she was a tender to one of the British frigates proved correct; as the sloop sailed closer, the old tars from the Wild Duck recognized their pursuer from weeks earlier. It was the Edward.9 Barry issued orders to load the Lexington's cannons, but still kept the gun ports closed.

The Americans waited quietly at their stations. Soon captain and crew would know if the drills and gunnery exercises had prepared them well enough for combat. All felt a mixture of anxiety, fear, and readiness as they waited for the fight to come to them. Barry's commanding presence on deck and his jocular comments kept many a sailor's knees from knocking. All the men could hear was the lapping of the waves against the Lexington's hull, the wind snapping at the canvas, and their captain's occasional low exhortations to keep calm . . . when suddenly the Edward fired a warning shot over the Lexington's bow.10

Lieutenant Richard Boger had an experienced crew of twenty-nine men aboard the Edward. The sloop carried six 3-pounders and several swivels; it was not as well armed as the Lexington, to be sure, but her crew was battle-tested and eminently more familiar with their guns than the Lexington's sailors were with theirs. The Edward had just finished escorting a packet through the Virginia Capes when she sighted Barry's ship.11 With orders to “intercept and carry into Virginia” any rebel vessels, Boger saw the brigantine as easy pickings. The Lexington again changed course as if to elude the little warship.12 As the Edward closed in on her prey, Boger took his speaking trumpet and bellowed orders for the Lexington to identify herself and “heave to”: bring the ship into the wind, in order to come to a complete standstill.13

Barry's response to Boger's demand was threefold. First, he took up his own speaking trumpet: “Continental brig Lexington,” he shouted over the water. Second, he ordered the Grand Union raised and the gunports opened. Finally, he roared, “Fire!” The port rail of the brigantine disappeared in the smoke of a broadside aimed at the Edward's starboard hull and bulwark. The battle was joined. Barry ordered the mainsail and main foresail reefed to keep better control of the ship during the fight and minimize damage to them.14

The Edward only took a hit or two from the broadside, fired by Barry's gun crews with more nervous enthusiasm than accuracy. But the broadside proved enough of a shock to Boger that he decided to change course, losing headway in the process. As he brought his sloop back into the wind, she ran into another broadside. Again, the results were negligible.

While Barry's greeting surprised Boger and his crew, they wasted no time responding. Boger kept his course west-southwest, heading for the Chesapeake. If he could put distance between himself and this rebel's superior firepower, he might reach other ships from Dunmore's fleet for assistance. The Edward's smaller guns, more accurately handled, soon proved deadly. Her cannonballs found their mark, splitting the rails and bulwarks of the Lexington. One shot felled three of Barry's men, killing two and wounding the other.15

It was a running battle. Despite the surer aim from his more seasoned hands, Boger could not scare off the Lexington and free his ship from the tenacious brigantine. Gunwales splintered, deck bloodied, the rebel ship still would not back off. Barry kept his men to their assigned tasks. Slowly but surely, his gun crews found their range and improved their accuracy.16 The Lexington, larger in size, sail area, and manpower, kept up its pursuit. Soon Barry took control of the fight. Now the Edward's bulwarks were being shot into splinters, menacing the crewmen and tearing her rigging and sails.17 For an hour, the two ships kept at their small guns; two young lightweights crudely pawing at each other while dancing around the ring.

Finally, Barry saw the opportunity he hoped for: the Lexington “crossed the T,” coming across the Edward's stern.18 For a few brief moments, the sloop was defenseless. The next round of cannon fire from the Americans resulted in a shot as lucky as it was deadly, smashing the Edward's stern just at or below the cabin, killing a British sailor. Water poured in fast; Boger sent a man to find a “plug”—a stanchion large enough to stop the incoming seawater—but none could be found of sufficient size. With his crew too small in numbers to maintain the fight, sail the ship, and keep the Edward's stern from flooding and eventually sinking, Boger was forced to reach for his speaking trumpet, ask Barry for quarter, and strike his colors.19

The crew of the Lexington, bloodied and exhausted, had just won their first victory at sea. It was also the first time British colors were lowered by a British ship of war in combat with the Continental Navy.20

The Americans quickly boarded their prize and assisted in plugging the Edward's stern, rendering her seaworthy for the voyage back to Philadelphia. Barry placed a prize crew on board and turned command over to his sailing master, Lieutenant Scott. The Lexington escorted the Edward back to the Delaware Bay.21 Before they departed, Barry handed Scott a euphoric report of his victory, to be delivered to John Hancock in Philadelphia:

In sight of the Capes of Virginia, April 7, 1776.

To the Continental Marine Committee:

Gentlemen, I have the pleasure to acquaint you that at one PM this Day I fell in with the sloop Edward, belonging to the Liverpool frigate. She enjoined us near two glasses. They killed two of our men, and Wounded two more. We shattered her in a terrible manner, as you will see. We killed and wounded several of her crew. I shall give you a particular account of the powder and arms taken out of her, as well as my proceedings in general. I have the pleasure to acquaint you that all our people behaved with much courage. I am gentlemen {& c} John Barry22

It was a succinct account with not one wasted word. Barry awarded no accolades to himself for his ruse, leadership, or courage. The praise was for “all our people.” His skills as a sailor and qualities as a commander were between the lines of his report. It would later be said that he was as popular with his men as any captain in the navy: with a minimum of casualties, a victorious battle under their belts, and a prize ship heading home (and shares in its condemnation awaiting them), the Lexingtons were ready to follow Barry anywhere.23

The ships parted company at Cape Henlopen. Sending the Edward limping up the Delaware to Philadelphia, Barry sailed the Lexington back to Little Egg Harbor, to repair his own ship and dispose of his prisoners.24

As the battered Edward struggled upriver, Philadelphia finally received news of Esek Hopkins's squadron, as the schooner Wasp and Captain Hallock sailed into town. The fleet departed the Bahamas on March 17, heading north with their holds full of captured ordnance and three prisoners, including the lieutenant governor of Nassau. Some of the Americans came down with “tropical sickness”—perhaps a euphemistic way of saying that the “Cask of Spirits” mentioned earlier resulted in everything from hangovers to alcohol poisoning.25 And while some sailors suffered the excesses of demon rum, others also complained of ill health, with pustules breaking out on their skin—symptoms of smallpox.26 Hopkins ordered the fleet to rendezvous at Block Island Channel below Rhode Island.27 On the way home, the Wasp was separated from the squadron by a storm; with his ship damaged and “14 Sick people” aboard, Hallock returned to Philadelphia.28 The Wasp barely made it upriver, in what Robert Morris called a “leaky and sickly” condition—also an apt description of her crew.29

Along the way, the Wasp passed the Betsy at Gloucester Point. The Betsy's destination was France, and among her passengers was Silas Deane, the first American envoy to the court of Louis XVI.30 Morris and Deane wrote back and forth to each other as the Betsy sailed toward the Capes. Deane nervously hoped “that as Capt. Barry has got out and will Cruize from Sandy Hook to the Capes of Virginia, No small [British] Vessels of war, will keep the Coast,” and attack Deane's ship.31 Morris planned to send the Wasp back down-river to escort the Betsy, if the latter would wait for her, but “I cannot find the Captain.” Morris wrote, “however I will have her fitted quick.” Four days later, the Wasp was ready.32

The Wasp reached Chester on April 9, and saw the battered Edward in the river, having picked up a pilot to get her to Philadelphia safely. Also at Chester was Lieutenant Colonel Francis Johnson of Anthony Wayne's regiment, who immediately penned a letter to his superior stating “that Captain Barre has been amazingly successful” and that “All The Prisoners are to go to Philada Thro' Jersey (saving one or two Seamen and three or four Negroes).”33 The letter, delivered by a dispatch rider, got to Philadelphia before the Edward crawled into the harbor. Quite a crowd turned out to see her; from Congressmen to servants, they beheld the first captured warship to arrive at an American port.34

News of Barry's victory sped throughout the colonies. In a letter praising his actions, the Marine Committee promised that the Edward “shall be immediately libeled in the Court of the Admiralty . . . the share thereof belonging to you, the Officers and Crew shall be deposited in the hands of your Agents and in every respect the utmost Justice Shall be done to all concerned. . . . We report our approbation of your Conduct, And beg you may signify to your Officers and Men that the Marine Committee Of Congress highly applaud their Zeal and bravery.”35 Eventually, the news reached London, in an “Extract of a Letter from Philadelphia” published in the Public Advertiser with a dateline of April 15: “This Morning was brought in here a Sloop mounting six three pounders and ten swivels belonging to the Leverpool Man of War. . . . She was taken off the Capes of Virginia by . . . Capt. Barry.”36

True to their word, the Marine Committee sped through the condemnation process of the Edward. Back at Little Egg Harbor, Barry procured what few stores the little village possessed to mend damages incurred during the battle. On April 8, with Lieutenant Scott and the first “prize” having arrived in port, the Marine Committee wrote to Barry that the St. Croix sloop “does not prove to be a prize, yet as the circumstances attending her Suspicions you did right.”37 Further, the committee sent “your Lieut. of Marines and some men” with Captain Hallock and the Wasp, to be landed at Cape May; Lieutenant Scott took a similar message with him to Little Egg Harbor should Barry still be there. The letter concluded with orders that the Lexington join the Wasp in giving safe escort to the Betsy “until you and Mr. Deane Shall think her out of danger of the Enemies Tenders and Cutters.”38 Scott arrived on or around April 12, but it wasn't until the fifteenth that Barry could comply with the committee's orders to catch up to the Betsy and escort Deane and Co. past the Capes. That day, Barry commanded the local militia's captain to “deliver the prisoners which I have taken out of the Sloop Edward, and to supply them with sufficient meat Drink and Lodging during their journey. . . . Mr. Robert Morris will satisfy you.”39 By noon Barry rounded Cape May, where Hallock “Sat [set] Capt. Barrey['s] pepel on Shore.” While retrieving them at Cape May, Barry learned that the Roebuck had pursued the Wasp until Hamond called off the “game” on account of darkness.40

Barry endeavored to catch up to the Betsy, following a course toward Bermuda he believed the Betsy would take before turning eastward so as to avoid British ships. By this time, Barry and the Lexington were becoming an obsession with Hamond. In a letter to Lord Dunmore he poured out his frustrations regarding Barry:

It is with great concern I acquaint yr Lordship, that Mr. Boger . . . was taken by this Brig I mentioned to you in my letter . . . she is now fitting out with great expectation as a Privateer and will undoubtedly be sent to the Capes of Virginia: and by not being known for an Enemy . . . will do a great deal of Mischief. . . . I would give more than I can express to have the Otter, or even the Otters Tender here for a few days, as without a small Vessel that can go in shallow water it is totally impossible (or at least very unlikely) that I shall be able to do any thing with this Brig Lexington. All the North side of Delaware Bay is encompassed with shoals & shallow water, having a channel of about 13 or 14 foot water within them; and this passage Mr. Barry is at present master of. I have chaced him several times but can never draw him into the Sea. . . . However, I trust if my good stars will be but propitious enough to me to send me any Vessel that can carry 50 Men, his reign will be of short duration, especially as his success of late has made him bold.41

As Hamond penned this letter, the Lexington was six hundred miles away, near Cape Roman on the South Carolina coast.42 On April 27, the Lexington's lookout sighted no less than seventeen sail to the southeast. Barry kept a watchful eye on them; when one of the larger ships began to stand toward him, the Lexington's captain took enough time to discern it to be a frigate, and gave orders to head northwest in a hurry. The chase was on. Barry ran out every inch of the Lexington's canvas.43

The hound in the hunt was the HMS Solebay, twenty-eight guns, led by Captain Thomas Symonds. The seventeen ships sighted comprised the British fleet under Sir Peter Parker, escorting British merchantmen. Symonds, “seeing sail in the NW Qr our Sigl to Chace could not come up with her ha[u]l'd our wind” and rejoined the convoy.44 The Solebay chased the Lexington for “eight hours . . . when the man of war quitted the chace and joined his convoy. Barry then reversed course and followed, with design to pick up some of the fleet, but discovering his foremast was sprung, he was obliged to alter his course.”45

With so much pressure from the wind on the Lexington's sails, her foremast was carried away. But despite this accident, the Solebay couldn't catch up with the American ship. Barry kept the wind at his favor, and nothing Symonds tried brought the Lexington within range of his bow-chasers. Given that the fleet seemed to be heading for Virginia (actually North Carolina), Barry set his course for home. Cloaked in the dusk, the Lexington slipped past Cape May on May 4.46

Daylight found not one but three British warships in Whorekiln Road, heading up the Delaware to Philadelphia, the Roebuck having been joined by the Liverpool and the Fowey. Once the Roebuck's mast-header spied the Lexington, Hamond instantly recognized her and began pursuit, running “with all my Studding sails.”47 Barry kept his ship hugging the Jersey shoreline and its shallows, eluding Hamond once more.48 The vexed Briton fired a long gun in frustration at his nemesis, and Barry sardonically returned the backhanded compliment with one of his diminutive 4-pounders.49 Low on supplies and ammunition, the Irishman gave orders to head upriver and home.

Philadelphia gave him a hero's welcome. “Capt. Barry in the brig Lexington returned from a cruise against the English Pirates” was the lead in the Pennsylvania Journal's article on his return.50 His deeds were the talk of the town, especially in light of the latest news regarding Esek Hopkins.

The Continental fleet was sailing back to Hopkins's home port, Providence, Rhode Island. They had just captured two British ships: the schooner Hawk and bomb-brig Bolton.51 On April 6, another sail was seen on the horizon, and the four largest American vessels took up the chase, catching up with her off Block Island.52 She proved to be the frigate Glasgow, under Captain Tyringham Howe, Charleston bound. Her twenty guns made her a formidable opponent, but as she was outnumbered four to one, Hopkins gave the orders to engage.

Where British tactics would have dictated forming a line of battle in order to pound the Glasgow into submission, the inexperienced Hopkins sent his ships at the frigate one at a time. Like a gang of young toughs that had cornered an experienced street fighter in an alley, each vessel took its turn at the Glasgow and came away the worse off. For over two hours, the outnumbered British ship bravely outran and outfought her enemy. The Alfred alone “receiv'd considerable damage . . . our, wheel, rope and blocks shot away.”53 Finally, the four American ships, their holds heavy with captured cannon and ammunition, and their bottoms foul from their round trip to the Bahamas, broke off the engagement.54

At first, Congress and the public believed Hopkins's version of the battle, as originally reported by the press. But soon writs from the crews about lack of payment (soon followed by similar complaints from officers) were quickly augmented by allegations of cowardice aimed at Captains Hazard and Whipple, and rumors of incompetence regarding Commodore Hopkins himself. Courts of inquiry were called. Whipple's court-martial, which questioned his judgment during the fight, cleared him; Hazard's found him guilty. Hopkins's politically connected appointment was beginning to look like a poor choice.55 He was later censured by Congress for his conduct, yet retained his command. The American Navy might not have yet learned how to fight like the British Navy, but Congress had learned the importance of family connections, in meting out levels of blame as well as in appointments.56

Barry also learned that the Edward was condemned at an Admiralty hearing. George Campbell, “Presenter for the Libellists,” presented “the Bill of John Barry Esquire [and] the Officers Marines and Seamen” of the Lexington and the “Thirteen united Colonies of North America” against “The Edward with her Guns Tackle Furniture and Apparel.” The Lexington fitted out for the “Defence of American Liberty . . . sailing on the high Seas . . . did discover pursue approach the Edward . . . burthen about fifty Tons . . . employed in the present cruel and unjust War.” The inventory included everything from “Guns Tac[k]le Furniture” to “10 E[m]pty Hammocks” and was promptly itemized for condemnation.57

Interrogations were administered; Lieutenant Boger did “declareth and confesseth” to the truth of the statements, including in his testimony “that there were four Negroes on board the said Sloop at the Time of her Capture that one of them called Pompey White he hath heard and believes is free. That the other three he believes are Slaves and one of them named James he has been told belongeth to one Mr. Anderson of Hampton that as to the other two knoweth not to whom they belong.” Along with the items Boger had seized from the ship Philadelphia Packet, the slaves were removed from the Court's list, to be returned to their owners.58

On May 1, the Pennsylvania Gazette ran an “Advertisement of the Sale of the Prize Sloop Edward.” The auction was held at the London Coffeehouse on the following day.59 The Marine Committee purchased the Edward, giving her to Joshua Humphreys for repairs; his talents soon transformed her into the ten-gun Continental sloop of war Sachem. She was the second acquisition of the Continental Navy since the Lexington's first cruise. Another brig, the Molly, had been refurbished by the tireless Humphreys and given to another Willing and Morris merchant captain: Lambert Wickes. He joined the roster of naval commanders with his renamed ship, the Reprisal.60

Barry's officers and crew got their first taste of prize money. Congress had broken down the disbursement of shares in the following manner: 10 percent to the captain: 15 percent divided between the marine captain, lieutenants, and masters; 12 1/2 percent divided between the marine lieutenants, surgeons, chief gunners, and carpenters; 15 percent between the midshipmen, warrant and petty officers; and the remaining 48 1/2 percent distributed among the rest of the crew. Handsome as it sounded, there was a catch—a very large catch. Since 50 percent of the full amount went to Congress, the above percentages for shares were actually only worth half as much—a far cry from the “captain and crew take all” approach of His Majesty's Navy.61

Precedent was also set for Barry's prisoners of war. Under the watchful eyes of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, Richard Boger and his junior officer signed a parole, swearing “We would not go farther than two Miles from Germantown, where we are ordered to reside, with leave of the Committee . . . that we will not bear arms against the said Colonies, nor carry on any Political Correspondence . . . nor give any Intelligence to any Person whatever . . . so long as we remain a Prisoner.”62 The committee passed a resolution that the “Mariners taken Prisoner by Captain Barry” were to be offered similar terms for parole, with instructions “to provide the Lodging on the most reasonable Terms.”63 Such gentlemanly arrangements for British prisoners were in stark contrast to the treatment of American sailors captured by the British (the prison hulks in New York harbor rival the Civil War's Andersonville for inhumanity). As an officer, Boger would be a valuable chip in negotiations over prisoner exchange.64

Once set ashore, Barry's prisoners were better treated than one of his own crew, who presented his “Petition of a Slave to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety”:

Sheweth that your poor Petitioner was Bought by Captain John Barry and taken to Sea in the Brig Lexington belonging to the Honorable the Congress and has since Sold him for the Same Money That he Paid for Him Besides Having Receved Your poor Petitioners wages and Prize Money-Therefore your Humble Poor Petitioner Requests that you Would take his Case unto Your Serio[u]s Consideration and order Him Such part of the Prize Money as you shall Deem fit and In so doing Your Humble Petitioner Will be for ever bound To pray and C Servant to Capt. Barry65

No record exists about the outcome of the slave's petition. Throughout the war, wages and prize shares earned by a slave at sea were paid out—to his owner.66

Barry's arrival in Philadelphia coincided with Hamond's return to the Delaware. With the Liverpool and her twenty-eight guns for company, Hamond sailed the Roebuck upriver to replenish her water supply and “reconoitre the enemy[']s force of the River.”67 Henry Fisher's alarm system went into action immediately. Signal guns were fired sequentially along the river while couriers galloped to each way station, handing Fisher's warning to the awaiting rider. Within minutes, Philadelphians knew enemy ships were approaching; within hours, they knew what ships were approaching. Barry and Humphreys busied themselves with refitting the Lexington and completing repairs.

The Roebuck and Liverpool were alongside Wilmington the next day. Their long guns put Philadelphians “into some Consternation for a short time,” Richard Bache noted in a letter to Franklin.68 Morris, as the vice president of the Marine Committee and as a member of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, ordered Barry to “Collect your officers and Men” and assist in the defense of Philadelphia. Barry and at least seventy of his men from the Lexington joined Captain Read aboard the Montgomery and Captain Wickes on the Reprisal. Every warship, row-galley, and floating battery from both the Pennsylvania and Continental navies headed below the crest of Fort Island (later Fort Mifflin), to give as warm a welcome as possible to Andrew Snape Hamond, R.N.69

Barry and Read got to the battle line on May 9 and were briefed on the previous day's actions. Thirteen row-galleys positioned themselves in the shoals—putting them about a mile from the frigates—and began firing at the Roebuck and Liverpool. The frigates, trying to maneuver to a point in the river where their guns could destroy the small American boats, returned fire. Most of the cannonballs from both sides splashed in the water, yards away from their targets. At dusk, the Roebuck attacked from the Jersey side of the river near Helen's Cove. Hamond intended to take out the row-galleys before nightfall. In his haste he forgot about the Roebuck's eighteen-and-a-half-foot draft; perhaps he had no pilot. Without warning, the Roebuck ran aground.70 The guncrews on the row-galleys kept firing their cannon until they were too hot to handle. That night, Hamond put some of his crew in the Roebuck's boats, serving as a night patrol against possible assault by the Americans. Captain Bellew sailed the Liverpool as close as he could to the Roebuck to protect the entrapped ship and serve as a getaway for Hamond's crew if required. When the tide began to rise, Hamond used every man and boat available to free his ship. After putting every British sailor to their utmost exertion, Hamond got the Roebuck off by 4:00 A.M.71

That morning, with ammunition and supplies running low, Barry fired off a note to Morris that “if the Lexington was Fit[t]ed she might be of service, for the More Thare is the Better . . . we shall keep them in play.”72 The second day's fighting was more of the same, with both sides jockeying for position, taking care to avoid the Roebuck's mishap. Finally, the British ships broke off the engagement. Hamond knew he was lucky; Charles Biddle “heard that Captain Hamond then said if the commanders of the galleys had acted with as much judgment as they did courage, they would have taken or destroyed his ship.”73

Philadelphia's citizens, having heard the constant echo of cannon fire for two anxious days, considered the Roebuck affair more a victory than a draw. The brave little row-galleys had served their purpose. John Adams wrote his wife, Abigail, “There has been a gallant Battle . . . in which the Men of War came off second best—which has diminished, from the Minds of the People . . . the Terror of a Man of War.”74 With the wood and canvas chess pieces back to their accustomed places on the board, it fell to the Marine Committee to come up with a plan to get the arriving merchantmen escorted past the Capes and safely upriver with their badly needed goods.

There were now four Continental ships at Philadelphia: Barry's Lexington, Wickes's Reprisal, the Hornet under Captain Hallock, and the Wasp, now under Captain Charles Alexander. The Marine Committee ordered them to work in concert along Cape May (where there was more shallow water in the bay than on the Cape Henlopen side), providing escorts at the Capes to arriving merchantmen when not harassing the enemy. Keeping to the Jersey shore and sailing into the bay at night gave the Americans a fighting chance in keeping the merchantmen—many carrying gunpowder and munitions—out of British hands.75

Thanks to Barry's recent achievements, his rendezvous for the Lexington's second cruise was quick and successful. Barry soon had a full complement of 110 men.76 After presenting his expenses for refitting and supplies on May 21, he sent the Lexington down the Delaware, picking up his fellow ships along the way.77

Barry discovered that Hamond and the Roebuck had departed Delaware Bay. Responsibility for the attack and capture of American shipping now fell to Captain Bellew and the Liverpool. With only one minor incident—Barry ordered a snow that had been bound for New England to return to Philadelphia due to its deep draft—the squadron came together under Cape May. Learning that the Liverpool had sailed beyond the Capes, Barry and Alexander sailed over to Cape Henlopen and met with Henry Fisher, who informed them that the Liverpool had taken a prize: “A Snow . . . she appears to be in ballast. . . . On Sunday [May 26] the Liverpool and her prize . . . went to sea. I am persuaded that the Liverpool was scar'd. . . . I went on board to give them [Barry and Alexander] the best information that I could in regard to the Liverpool. . . . They went on to Cape May for the rest of their fleet, and now they are all under our Capes in quest of the Pirate.”78

Barry and Alexander returned to Cape May, where they found the Reprisal and Hornet with a privateers' prize, the Juno, which had been chased by the Liverpool and gotten to the shallows of the Overfalls, the same tactic Barry had used with Hamond and the Roebuck. That gave Barry an idea. Leaving the Wasp to escort the Juno up the Bay, the other three American ships headed back to Cape Henlopen and out to sea. At 7:30 A.M., despite “Fresh Gales and hazey” conditions, the Liverpool “Made a chace to be [a] Ship a Brig and a sloop arm'd Vessels belonging to the Rebels.”79 It was an encore performance of Barry's cat-and-mouse game with Hamond.

For three hours the Liverpool chased the smaller vessels. At 10:30, Barry ordered “heave to,” and the three American vessels turned into the wind, coming to a dead stop almost immediately. Aboard the Liverpool, Bellew ordered “Beat to quarters!” It was obvious that the Liverpool would easily overtake the Americans ships. Bellew must have relished this chance to finish off the rebel captain who had sorely frustrated Hamond. Another half-hour put the Liverpool ever closer to the three Yankee ships.80

Though caught up in the moment of the chase, Bellew still had the foresight to order soundings, sending a midshipman toward the bow with the “lead line”—a twenty-fathom (about 120 feet) line of rope with a six- to nine-pound lead weight attached, hollowed out at one end and filled with tallow. The young officer swung the line over his head several times in an arced, pendulum-type motion, then flung it into the water in front of him; by the time it came back alongside where he was standing it was perpendicular to the bottom, where it could measure depth as well as give the nature of the seabed itself, with samples sticking to the tallow.81 Every couple of minutes, the midshipman called back his findings to the quarterdeck.

Suddenly, at 11 o'clock, Barry ordered his ships under way. With the wind filling their sails, they headed for the Overfalls, where soundings vary from as much as seventeen and a half to three and a half feet within as little distance as two hundred yards.82 Bellew continued his headlong pursuit; soon his quarry would be within range of his guns. Then the midshipman's alarmed cry rang out from the bow: the Liverpool was in only four fathoms of water. Quickly, Bellew gave orders to wear ship. In an instant, his crew's emotions swung from excitement to dread. They fairly jumped to their orders; now it was the Liverpool's turn to swing into the wind to keep from running aground and becoming a sitting duck for the rebel ships. Shortening sail, the frustrated Englishman headed back to Cape Henlopen.83 Barry came within seconds and inches of another capture.

Barry's attempt to run the Liverpool aground gave him the chance to see the Hornet in action. Leaking and slow, she would not be of much use in future encounters with His Majesty's warships. Barry kept her anchored at Cape May as more of a presence than a true threat.84 He sent Wickes and the Reprisal to convoy the merchantmen out of the bay.85

The Liverpool soon disappeared from the Capes; Bellew sailed in pursuit of “several sail” and headed hundreds of miles below Cape Henlopen in chase.86 At the same time, Congress declared that the “Committee of Safety of Pennsylvania be empowered to negotiate with Captain Bellew . . . for an exchange of the prisoners on board of the Liverpool . . . to deliver up Lieutenant Boger and Lieutenant Ball in the exchange.”87 Congress was determined to be honorable and aboveboard in its treatment and actions toward naval prisoners of war. British officials, as we shall see later, were not so disposed.

Bellew wrote a report to Admiral Shuldham at Halifax of his encounter with Barry's squadron in “Cape Mary Road,” describing it as “a large Privateer Ship at Eighteen Three Pounders, a Brig of Sixteen Sixes and Fours, and a Sloop of Ten Six Pounders.” While reporting the loss of his tender, and the other Continental successes along the coast, he did find solace in the fact that he captured “a small vessel laden with linen and Twelve thousand Dollars . . . the property of Willen and Morris . . . two most Notorious rebels.”88

Now back to sea and on the prowl, the Lexington's lookout sighted two sail: one due east, too far to be recognized; the other a sloop of war, coming out of Whorekiln Road to the southeast. This was the Kingfisher, captained by Alexander Graeme, recently from Nova Scotia and a cruise in the Bay of Fundy, with orders to join the Liverpool at the Capes.89 Seeing the Kingfisher stand for the other ship, now identifiable as a merchant brig, Barry lost no time in making for the same target. With the advantage of the shorter leg in this triangular pursuit, Barry brought the Lexington alongside and boarded her around 5:00 P.M. She was a Wilmington brigantine under one Captain Walker, returning home with a hold containing powder and arms. Sizing up the situation, Barry ordered the munitions transferred aboard the Lexington. He offered to bring Walker and his crew aboard as well, but Walker declined abandoning his ship to the enemy—a decision that Barry understood. With the precious cargo in his hold, Barry departed at sunset. Within an hour Graeme captured yet another prize for the British.90

Vigilant Henry Fisher, in his report to the Committee of Safety on June 11, noted that “lucky for us before the Pirate [Bellew] Boarded our Brave Capt. Barry had been on board . . . in sight of the Kingfisher.” Fisher's report was “delivered by the Whale Boats as far as New Castle, and from there, by Land, the Torys having Cut that Communication.”91 It was becoming increasingly risky for Fisher to carry out his very dangerous and often unappreciated job.

In recognition of his actions against the enemy, Congress awarded Barry command of the Effingham, one of the four frigates being built in Philadelphia.92 At Cape May, Barry got word of his imminent appointment from John Baldwin, newly appointed commander of the Wasp. When this news reached the ambitious Samuel Davidson at Fort Island, he immediately wrote Robert Morris: “Permit me Sr; to Beg your Interest to command the Lexington, when Captain Barrey Resigns.”93

The details and paperwork for Barry's new command went through the office of the Marine Committee's Secretary, John Brown. Like Barry, Brown had emigrated from Ireland to Philadelphia as a young boy, and was soon working for Willing and Morris. Darkly handsome, with piercing brown eyes and an Irishman's “gift of the gab,” Morris trusted Brown implicitly. Three years Barry's junior, Brown was already a good friend; the war years only deepened their admiration for each other. In Brown, Barry had both a confidant and trusted adviser.94

Baldwin also had new orders in hand: the Reprisal was to sail on a diplomatic mission to Martinique, the Hornet to return to Philadelphia for repairs, and the Wasp to rejoin the Lexington at the Capes.95 Baldwin also carried a dispatch from Morris. Under his responsibilities with the Committee of Safety, Morris alerted Barry of the arrival at the Capes of the brigantine Nancy, commanded by one of Barry's old friends, Hugh Montgomery. The Nancy was returning to Philadelphia with that most valuable and volatile of cargo—gunpowder—from St. Croix and St. Thomas: 386 half-barrels, to be exact.96

The Reprisal's mission to Martinique was thwarted by the arrival of a third British warship, the frigate Orpheus, Charles Hudson in command, having finished a “Cruze between the West end of Long Island and Cape Henlopen.”97 With a growing fleet of merchantmen assembled at the shoals under Cape May, Barry told Wickes to wait for the best opportunity to slip past the British. The large number of ships was duly noticed by the British on June 24, as the Kingfisher's Graeme recorded: “Saw fifteen sail at anchor under Cape May Lighthouse WbS 5 or 6 miles.” The next day's report shows a further increase in ships: “8 am saw 18 Sail of Pirates and Merchants . . . at anchor off Cape May.” Tensions were mounting on both sides.98

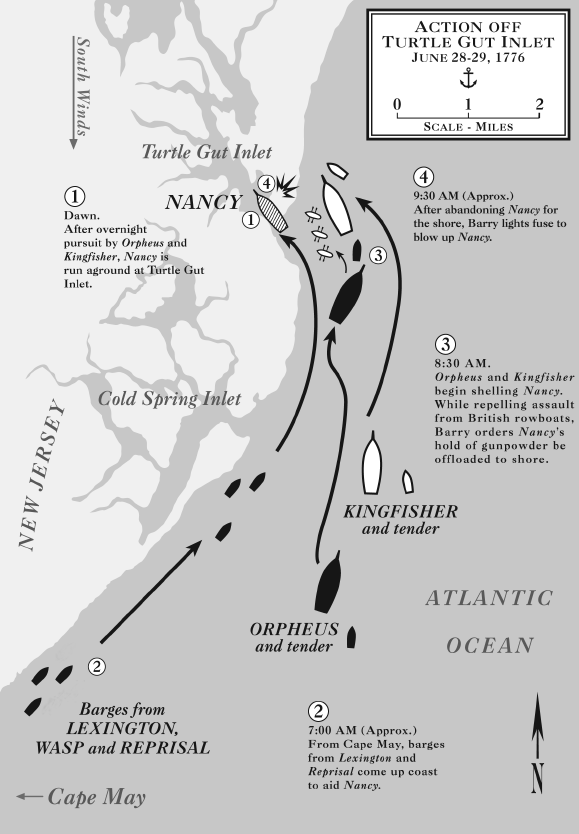

By mid-morning on June 28, 1776, the weather worsened: “Mod't with rain,” was how Hudson described it in his journal.99 Soon his lookout called out, “Sail Ho!” It was the Nancy, already pursued by the Kingfisher—Graeme had been “in chace” since 3:00 A.M. The Orpheus, off Cape Henlopen lighthouse, spotted the incoming Nancy “at 11 AM [and] gave Chace to sail to the No[rth]ward.” By late afternoon the Nancy was “standing in for Cape May,” and the Kingfisher “weig'd and stood for the Cape as did the Orpheus and Tenders.”100

Eminently aware of his surroundings, Montgomery sailed the Nancy toward the shallower waters outside the oddly named Turtle Gut Inlet, about seven miles northeast of Cape May. The darkness and shallows were a good defense against the British ships and their following tenders, and the enemy's unfamiliarity with the waters guaranteed there would be no pursuit or attack on the brig until dawn. Miles away, the Lexington's lookout saw the approaching ships come over the horizon and hailed Barry of the Nancy's arrival, along with her pursuers.

Now with darkness came the waiting game. Barry signaled Wickes and Baldwin to come aboard the Lexington. The captains and their officers were no sooner up the gangway when they were brought to Barry's cabin for a council of war to create a plan of action.101

The three captains determined that the “light winds” would keep the Reprisal from taking part in any action, so Barry and Wickes decided that Reprisal's barge would assist the other two Continental ships. Lambert's younger brother, Richard, insisted on commanding the barge. After he “refused several Times,” the older brother “at Las[t] was prevailed on to let him go.” Elated with this chance to prove his courage and leadership, Richard set out in the barge, joining the Lexington and Wasp, who were at anchor off Cape May. Barry ordered the ships to drop anchor in Whorekiln Road, where he could observe the unfolding action and take steps accordingly.102 His crew attended their watch or lay in their hammocks, sure in the knowledge that morning would bring battle.

Aboard the Nancy, Montgomery had assembled his meager crew and laid out the situation they were facing. He also gave them a choice: those who wished to go ashore in the ship's boat were free to do so, but he was determined “to defend the munitions of war at all hazards.” Not a man departed the ship, now riding at anchor several miles off of Turtle Gut Inlet.103 The inlet would give Montgomery the chance to unload his cargo and get it ashore. The shallow water surrounding its entrance would prevent the larger British ships from entering. Although the Nancy would still be in range of their guns, the British would have to send boarding parties in longboats to make a fight of it.

The Orpheus's Hudson began the day with breakfast and a flogging: he “punished Thos. Sandower for Breach of 2 Articles of war w[ith] one Dozen Lashes.” Hudson either liked the cat-o'-nine-tails or had a difficult crew; he had a dozen lashes meted out to another sailor just two days previously. The morning weather was more of the same: “Light breezes and hazy and small rain.” One of Barry's favorite allies showed up that morning—fog.104

Gray daylight gave witness to the resumed chase: “3 Leagues Dist to the Et Ward”—about ten miles—the Nancy was sighted and pursued once again by the Orpheus, the Kingfisher, and “2 Tenders in Chace.” Barry, seeing that the Lexington and Wasp could not be of any assistance on the Nancy's behalf in open water, told young Wickes to send his barge immediately out to the Nancy, board her, and sail her into shore, once again using the shallows as a defense against the British warships and their larger drafts.105

No sooner had Wickes departed for the Nancy than Barry ordered that the barges from the Lexington and Wasp also be lowered. Deciding that the “light winds” would keep the other two American ships from playing a role in the fight, Barry got into the Lexington's barge: he would personally lead the action.106 He also made sure that his best gunners came along. Under his command, the sailors in the barges manned their oars and began rowing furiously up the coastline toward Turtle Gut Inlet. They could hear the gunfire of the enemy ships' bow-chasers at the Nancy. The brigantine, her hold full of gunpowder, was one chance shot from being blown to bits.

Young Wickes's barge reached the Nancy at the entrance to the inlet. After a quick introduction, he and Montgomery determined that the quickest and safest course of action was to “cut her Cable and runn her a shore in order to save her Cargo if possible.”107 The enemy cannon began to boom at them, though not yet finding their range. The Nancy headed for the shoreline, entered the inlet, and soon struck ground hard and fast. It was now just past sunrise.

Within minutes, Barry's barge reached the Nancy. Once aboard, he hardly had time to greet his old colleague Montgomery and young Wickes. He immediately issued orders to unload the gunpowder, while he and his men manned the Nancy's six 3-pounders. As his men “cut loose the guns,” Montgomery's crew and the sailors from Wickes's barge began unloading the nearly four hundred half-barrels of powder in the hold.108

The Kingfisher, her draft much lighter than that of the larger Orpheus, got as close to the inlet as Graeme could manage without running aground. Her first broadside sailed over the Nancy and the feverishly working Americans. Operating like a bucket brigade, they passed each half-barrel one man to the next, up from the hold to the deck, and down to the Nancy's boats. By now, the two enemy tenders reached the Kingfisher and added their guns to the bombardment. Once Graeme's gunners found their range, he ordered four rowboats lowered to attack the Americans.109

The gunners from the Lexington, their courage already proven during the taking of the Edward and the battle with the Roebuck, had the Nancy's 3-pounders primed and ready. Along with other sailors armed with muskets, they awaited their captain's orders. Barry, too, was patient. Once the enemy boats were within musket range, Barry's gunners took dead aim at them, and he bellowed, “Open fire!”

A furious broadside and a volley of musketry swept the attackers with deadly results, and “these Boats were soon beat of[f] & sent back from whence they came.” Barry's men did their job well, damaging one longboat so badly that she was of no further use in the battle. As the British rowed hurriedly back to their ship, Barry directed his gunners to take aim at the Kingfisher and her tenders. All the while, their comrades kept unloading the gunpowder onto the boats on the leeward side of the Nancy. Once so full that they were about to swamp, the boats were rowed to shore, quickly unloaded, and sent back again for more half-barrels.110

Around 8:30 A.M., the Orpheus closed in.111 Her 9-pounders opened up in concert with the Kingfisher's guns. The Nancy was being pulverized. Her hull was shot full of holes, the main mast shot in two, and her deck was littered with spars, canvas, rope, and tackle.112 Graeme ordered the Kingfisher run within “3 or 4 Hundred yards” of the Nancy, putting his ship right at the entrance to the inlet. The British bombardment went on for another half an hour. Amazingly, for all of the flying iron, lead, and splintered wood, only one American sailor had been wounded thus far.113

At 9:00 A.M., Hudson ordered two boats from the Orpheus to join the Kingfisher's three remaining boats in a new assault on the battered Nancy.114 As Barry watched them come on, another British broadside whistled across the inlet. One of the cannonballs slammed into the Nancy's galley, smashing it to pieces.115 The combination of more advancing enemy boats and the improving aim of the British gunners now made the situation aboard the Nancy untenable. Barry's next order was immediate and direct. While his gunners continued to return fire from the Nancy, the barges took the other Americans to the shore, with orders to return for Barry, Montgomery, and the gun crews.

Only 121 of the 386 half-barrels remained aboard. Barry was determined that the Nancy and her remaining gunpowder would never be taken by the British. He ordered the gun crews to move 30 or 40 half-barrels from the hold to the captain's cabin. With Montgomery in tow, he laid a fuse-like line of gunpowder running from the cabin along the deck and down into the hold. Next, taking the ship's mainsail, the two captains poured 50 pounds of powder onto it and folded the canvas several times over. Dropping two red-hot coals on the sail's edges, he ordered the remaining men to scramble over the side, into the last barge.116

While the Americans had removed “265 heavy Barrels of Powder[,] 50 Muskets[,] 2 three Pounders[,] the Swords[,] and about 1,000 pounds wort[h] of dry Goods” from the Nancy during the fighting, Barry had forgotten to haul down the ship's colors.117 One “daring but fool hardy seaman,” coincidentally named John Hancock, leapt back onboard, took down the Grand Union, jumped into the water, and was hauled into Barry's barge.118 As they rowed to the beach, the advancing British boarding party was being peppered by musket fire from the Americans already ashore. It took the British nearly half an hour to reach the abandoned Nancy, “during which Time they [the Americans] killed several of their Men which they saw fall over board and others wounded.”119 Barry's makeshift fuse continued to slowly burn its way toward its two destinations of cabin and hold.

The Kingfisher's longboat took the lead in the race toward the abandoned Nancy. Despite the brigantine's decimated condition, a prize is still a prize—especially one so fiercely contested. Once he waded onto the strip of beach, Barry again took command. With “one or two small cannon mounted onshore”—probably swivels—he directed the firing on the enemy rowboats from the beach.120

At last the crew of the Kingfisher's longboat, commanded by her master's mate, came under the Nancy's stern. Armed to the teeth, they scrambled aboard with the cheers from their fellow sailors ringing in their ears—just as the sparks from Barry's fuse reached the barrels of gunpowder in both cabin and hold. In that split second, with a deafening blast, the Nancy and the British boarding party disappeared.

It was said that the explosion was heard “40 miles above Philadelphia.” It sent the men aboard the Nancy and those in the closest rowboats flying “30 or 40 yards high,” along with pieces of the exploded ship. As the smoke cleared, sailors on both sides could see the gory debris fall back into the inlet, as if the heavens refused it. “Eleven bodies, two laced hats, and a leg with a white spatter dash” dropped back into the water along with the shattered remains of the brigantine.121 The surviving, dumbstruck British tars, their remaining boats “in a shattered Condition [and] weakly man[n]ed,” rowed back to their ships.122

The guns on both sides were silent until they returned. Suddenly, a fierce cannonade from the British ships exploded onto the beach at Turtle Gut Inlet, but only one American was hit, “Shott through the arm and body.” It was Richard Wickes. A cannonball took his arm and half his chest away. Fresh from the Reprisal, Lambert Wickes arrived on the beach at the head of his reinforcements just as his younger brother died: “I arrived just at the Close of the Action Time enough to see him expire . . . Captn Barry . . . says a braver Man never existed.”123

Taking Richard Wickes's body, the American sailors left the spit of sand they fought over that morning. The powder was stowed in the Wasp's hold and sent up the Delaware. “At 2 weighed and made Sail,” Hudson briefly noted in his journal.124 The British returned to Cape Henlopen.

As before, Barry had taken long odds, assessed the best plan that could succeed, and beaten the British. The Nancy was destroyed, but the Wasp would reach Philadelphia safely with the desperately needed gunpowder. Despite superior firepower, the “butcher's bill” was far heavier for the British. But the victory brought no cheers or satisfaction among the Americans, and Barry was particularly saddened by the death of the gallant young Wickes.125

The next morning—Sunday, June 30—the men of the Lexington and Reprisal gathered to mourn their shipmate at the log meetinghouse in the small village of Cold Spring, just north of Cape May. Under the same light breezes of the day before, the American sailors, with “bowed and uncovered heads,” filed inside and sat on the long, rough-cut wooden pews. After “The Clergyman preached a very deacent Sermon,” Lambert Wickes and the Reprisal's officers silently hoisted the coffin. Shuffling under its weight, they carried it outside to the little cemetery, and laid their comrade to rest.126

Lambert Wickes now faced the task of informing his family in Maryland of Richard's death. On July 2, in a sad but disjointed letter to his brother Samuel, he mentioned Richard's death among a list of the items—including the sugar and “one Bagg Coffee” that accompanied the letter. “You'll disclose this Secret with as much Caution as possible to our Sisters,” he pleaded. He quoted Barry's report that Richard “fought like a brave Man & was fore most in every transaction of that day,” dying for the cause of the “united Colonies.”127

By the time Lambert's package reached his family in Maryland, the “united Colonies” ceased to exist as well. The same day Wickes posted his letter, Congress approved the Declaration of Independence. Barry, Wickes, and the rest of the Continental Navy were now fighting for the survival of a new country: the United States of America.