CHAPTER ELEVEN

ATALANTA AND TREPASSEY

WITH BARRY'S ORDER, “BEAT TO QUARTERS!” ringing in their ears, the Alliances rushed to their battle stations: gun crews to their assigned cannon, marine sharpshooters to the “fighting tops,” and the rest to their duties with rope and sail-assignments that looked to be of little benefit this day.

Below deck, acting surgeon Joseph Kendall entered the cockpit—the dark, cramped quarters for the midshipmen and master's mates. Aided by ship's carpenter Charles Drew and his mates, Kendall prepared for eighteenth-century triage.1 They laid down a platform of planks about ten feet square which they covered with a stretched sail. Bedding was carried in, as were some beds for wounded officers.2 Kendall then set out his equipment:

[Surgical] instruments, needles and ligatures, lint, flour in a bowl, styptic, bandages, splints, compresses, pledges spread with yellow basilicon or some other proper digestive . . . the medicine chest . . . wine, punch for grog, and vinegar aplenty. . . . A bucket of water to put sponges in, another to receive blood from operations. . . Dry swabs to keep the platform dry . . . A water cask . . . to be dipped out as needed.3

Thus prepared, Kendall, his mates, and the “Loblolly Boys”—youngsters named after the gruel served in sick bay—were ready for the horrors to come.4

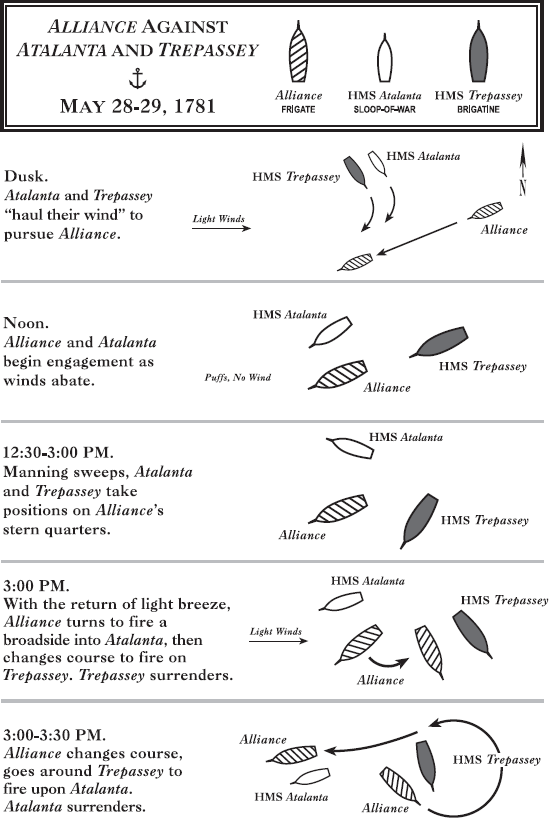

Up on the quarterdeck, Barry ordered his colors hoisted. Once raised, they hung limply on the flagstaff like a dolorous telltale. With little wind, the ships made progress by inches, drifting toward the coming confrontation on an ocean surface smooth as glass. It was noon before the British vessels came up on either side of the Alliance: the Atalanta on her starboard, with the Trepassey slowly approaching but not yet “on [Alliance's] larboard quarter.” Edwards determined that the Alliance was “about two cables lengths to leeward [when] she hoisted Rebel colours.”5 Barry estimated the distance as “within Pistol Shott.”6 Taking his speaking trumpet, he leaned over the quarter-rail and hailed the Atalanta: “Ship Ahoy! What ship is that?”

“Atalanta, Sloop of War, belonging to His Britannic Majesty,” Edwards replied.

“This is the Continental Frigate Alliance, John Barry, I advise you to haul down your colours.”

“I thank you, Sir,” Edwards replied. He paused a moment. Then, with understated bravado, he added, “Perhaps I may, after a trial.”7

Edwards hoped to keep the conversation going long enough for the Trepassey to come up into position, but Barry had eyes. He knew what lay behind these prolonged pleasantries, and saw no reason to delay the inevitable when, just at that moment, the wind completely died. For a second or two, the only sound aboard the ships was the useless flapping of canvas against the masts and spars above the silent and ready gun crews. Barry broke the silence. “Fire!” he commanded.8

The broadside raked the Atalanta, smashing into her bulwarks and taking out some of her rigging. Edward's second-in-command, Lieutenant Samuel Arden, was struck by a cannonball that took his right arm off. Taken below, he only stayed long enough to have his stump cauterized by the surgeon “and the instant it was dressed, resumed his [station].”9

After his initial broadside, Barry gave the order to “wear ship”—but while the Alliance's helmsman could turn her, there was no wind to propel the frigate. Aboard the Atalanta, Edwards commanded his men not to fire. The Trepassey was moving up, using the one advantage she and the Atalanta both had over the Alliance this day: oars.10

Immediately Edwards ordered his men to “Man the sweeps” while the Trepassey's crew rowed hard and furiously, determined to assist their comrades aboard the Atalanta.11 Their exertion backfired. The Trepassey was going too fast. Edwards watched in horror as, “With too much way and in heading [Alliance's] Quarter,” the Trepassey “shot abreast of her.” Smyth's overzealousness proved fatal. As his ship glided past them, the Alliance opened fire. The still waters gave Barry enough time to slam two devastating broadsides into the Trepassey, sending splinters flying around the deck, slicing the rigging to bits and killing several men, including Smyth, who dropped where he stood and was dead before he hit the deck.12

Winslow, the master's mate, was standing close to Smyth when he fell, and “sent to Lieutenant King to acquaint him [of Smyth's death], in order to his resuming the command.” King ordered the men to keep rowing, now in a frantic attempt to get the Trepassey out of the range of the Alliance's heavier guns.13

By now Edwards had the Atalanta's sweeps out. In a move of sheer courage and audacity, he ordered his men to row the Atalanta between the Alliance and Trepassey, taking yet another fearful broadside that further damaged her masts and rigging, but of small consequence as long as there was no wind. Once the Trepassey was safe, Edwards's crew kept right on rowing until the Atalanta was in a position of minimum danger and maximum advantage. With the Alliance “laying like a log,” the British ships were “athwart our Stern and on our quarters”: the Atalanta on the Alliance's starboard quarter, with the Trepassey “on the leeward side.”14 The Alliance was now caught in a deadly crossfire. Between the two enemy ships, fifteen 6-pounders were brought to bear, their crews taking calculated aim against the nearly defenseless Americans.

Barry had dealt with the treacherous Atlantic winds during this entire voyage, but this absence of any breeze was the cruelest trick of all. Unlike her sister ship the Confederacy, the Alliance was not a galley—she had no sweeps, nor could Barry lower long boats to row her out of danger, for any Americans manning them would be slaughtered. Without a wind, the Alliance could not get close enough to board either ship. She may as well have been mired in mud.

Seeing Edwards's strategy unfold, Barry ordered his gunner, Benjamin Pierce, to remove some of the 9-pounders from their lines and bring them into an improvised position where they could be used against the enemy.15 Smoke from the cannon fire hung over the deck like an acrid, stinging fog. Although they were just yards away, the ships could hardly see each other. Soon the only thing the combatants saw was the flash of cannon fire lighting up the hanging smoke, followed by the instant crash of the iron splitting their wooden walls.

The battle was now over an hour long, and clearly going against the Alliance. Barry's gun crews manned the 9-pounders and cohorns, while Parke's sharpshooters kept up their volleys from the tops.16 Unerringly accurate as the marines were, they could not equal the pounding their shipmates were being subjected to below. The Atalanta and Trepassey were now alternating their fusillades, mixing cannonball with grapeshot, which consisted of clustered, walnut-sized balls mounted on a wooden disc or packed tightly in a canvas bag. Upon discharge they separated, and ripped indiscriminately into ship and sailor alike.17 At such close range, Edwards also ordered the guns' powder charges reduced: this eighteenth-century technological trick ensured that the cannonballs striking the Alliance would tear longer and deadlier flying splinters through the air.18

Aboard the battered Alliance, “We could not bring one-half our guns nay oft times only guns out astern to bear on them,” Kessler recalled. Soon he was hit, wounded in the leg.19 Bulwarks and rolled hammocks were poor enough defense when ships fired on each other half a mile away. They provided little protection now.

In a situation growing more and more hopeless, Barry stood tall on the quarterdeck. Throughout the battle, he directed the best defense he could for his men and his ship. He gave commands in a clear, steady voice, and his presence, unaffected by the iron and lead flying around him, gave hope and renewed confidence to the Alliances, even as their comrades fell around them. In the fighting tops, Marine Lieutenant Samuel Pritchard suffered a direct hit by a 6-pound ball. Marine Sergeant David Brewer, son of an army colonel, was shot through the head and died instantly at his post. George Green, one of the mutineers, was impaled by a flying splinter.20

Below deck, it was all that Kendall could do to not be overcome by the sheer numbers of dying and wounded placed one after another on his makeshift operating table. His experiences as an army surgeon, traumatic as they were, had taken place a safe distance from the battlefield, under a tent and on solid ground. Now he was forced to perform his duties while sand and more sand was continuously poured on the floor to sop up the blood and keep Kendall and his aides from slipping in gore. At least the still waters minimized any unexpected movement while he did what he could with scalpel, tourniquet, and saw, using what laudanum he had to tend to the wounded and dying.

Sometimes several men were brought to Kendall at once, forcing him to prioritize and order his assistants to use stopgap measures for those who had to wait for care. He turned a deaf ear to the cries and moans of his patients, not out of cruelty but in order to keep his focus: looking, probing, and assessing each wound.21 He took on different roles at a moment's notice: that of bos'n to the slightly wounded, patching them up and gruffly sending them back into the carnage above; and that of a skilled “sawbones,” using the swiftest means possible to save a life. There was no time to be father confessor for those poor souls like Pritchard, only a quick glance, then, “Next!” and they were carried away—and another victim was immediately placed before him.

By now the wounded sailors who could move were assisting their comrades above, bringing up gunpowder and cannonballs to maintain the fight. They handed these to the ship's boys (not yet known as “powder monkeys”), who scurried back and forth between the hatchway and their stations. The number of fighting sailors was thinning out. Barry and his men were soaked in grime and sweat. The air smelled of blood and sulfur. The Alliance was being taken apart, not by the wind but by the lack of it.

At nearly three o'clock, thick clouds of smoke seemed to rise from the water, enveloping the three ships as if they were Macbeth's witches, and the motionless Atlantic their cauldron. The ocean was still enough to perfectly reflect the carnage above it. Aboard the Trepassey, another broadside of grapeshot was being loaded. The gun crews went through their steps, and on “fire!” linstock touched base ring. With a loud roar, grapeshot flew in a withering volley at the Alliance's quarterdeck.22 Until this instant, John Barry had gone untouched in his battles with the British.

Not now. A grape ball slammed into his left shoulder. The impact threw him on his back, and he hit the quarterdeck with a sudden thud. Dazed and shocked, he got halfway up, not yet feeling any pain. Still trying to clear his head, the pain hit him hard, and blood began soaking his uniform. Hacker and the other officers ran to him, offering to help him below. Once back on his feet, he waved them off. He would not be moved from his post. For a few minutes he remained on the quarterdeck, directing the action, while his voice grew noticeably weaker. Bleeding profusely, he became lightheaded, and standing became difficult. Barry's remaining on deck was not adding further inspiration to his officers and men. Instead, it was changing their focus from their duties to their commander's wellbeing—a sentiment that endangered them as well. Once more, Barry's officers begged him to go below.23

Finally, he relented, having remained “on the quarterdeck untill by the much loss of blood he was obliged to be helped to the cockpit.” Turning the quarterdeck over to Hacker, he let the wounded Kessler and several others carry him below.24

In the cockpit, Kendall received word of Barry's being brought below, and the captain became his immediate priority upon arrival.25 With a loblolly boy to assist him, Kendall removed Barry's coat and cut away his shirt, checking the hole to see how much of the shirt may have gone in with the ball. The surgeon ordered Kessler and the other men who had carried Barry below to remain. He would need every available hand to hold Barry down while he began his examination. If Kendall had any laudanum, he gave the captain a dose; if not, a pannikin of straight rum would be administered, to hopefully dull the pain.26

A single grapeshot was about an inch and a half in diameter—larger than a musket ball. To further complicate Barry's condition, grapeshot was made of iron, not lead as used with musket balls. Lead deformed on impact, but iron did not; therefore the soft tissue damage to Barry's shoulder was maximized. Whether it struck the collarbone or the top of the shoulder is not known; as Kessler said, he was removed from the quarterdeck “after much loss of blood,” which leads one to question whether the brachial artery had been hit.27

American naval surgeons, trained according to British precepts, took quick and aggressive action in treating such a wound, believing that to be the more humane approach. While a probe was one of the tools of the trade, a finger was used as often as not. One surgeon from these times insisted that a finger be used; “I could never bring myself to thrust a pair of long forceps the Lord knows where, with scarce probability of any success.”28 The practice of bleeding the wound to extract “impurities” was not necessary—Barry had lost enough blood already.

Next, Kendall used his retractors, widening the wound further. The resulting pain would send any man into pure agony. If the brachial (or any other artery) was damaged, they were tied off or cauterized. If the grapeshot had splintered the clavicle, Kendall cleared out any bone fragments, and expelled any grumous blood from the wound.29

The wound thus opened, and with Barry flat on his back in quiet suffering, Kendall took his bullet forceps—a scissorlike instrument with cupped ends—to reach the projectile, and cut into the wound. Widening around the grapeshot (and adding more suffering to Barry's condition), Kendall grasped the forceps around the projectile. Slowly, he removed it from Barry's shoulder. The original 1 1/2-inch hole was considerably wider now. With the grisly piece of iron removed, Kendall let the wound bleed awhile. Then he cleaned the area out, using straight turpentine or a mixture of turpentine and egg yolk. Either would send the most stoic of souls into further agony. Finally, after leaving a channel open to permit the wound to drain, Kendall dressed Barry's shoulder with lint dipped in oil.30 By this time, Barry could very well have lost consciousness or gone into shock.

No sooner had Barry been carried below deck when another broadside slammed into the Alliance, just missing Hacker but instantly killing quartermaster William Powell at his post, manning the ship's wheel. The Alliances returned fire. While they were reloading, a shot from the next British cannonade carried away the American flag. The Alliance's silent guns “led the Enemy to think that we had struck the colours”; the British tars “manned the[ir] shrouds & gave three cheers.”31 These “huzzahs” came from the cracked lips, parched mouths, and lungs raw with smoke of a jubilant, exhausted enemy, gratefully believing that their encounter in this deadly hornet's nest had ended, and that they were victorious.

But it was not over. Two of the Alliance's officers stepped over Powell's body; one took his place at the helm, while the other snatched the stricken Stars and Stripes, and “the colours were hoisted by a miz[z]en brail.” Before Edwards could take his speaking trumpet and inquire through the manmade fog if the Americans were surrendering, the Alliance's “firing began again,” and the British realized their mistake. Both enemy ships resumed their onslaught. Aboard the Alliance, seaman David Cross was killed; Fitch Pool, Barry's clerk, went down with a severe wound.32

From the quarterdeck, Hacker watched the unrelenting dismemberment of ship and seamen with growing concern. He was a six-year veteran of the war, but he had never been in a battle like this. Nor was he very lucky when it came to fighting. Wherever he looked, he saw mounting defeat: sails full of holes, rigging in tatters, the deck awash with blood and strewn with debris—all on a frigate crippled by lack of wind. He conferred with the surviving officers about the deteriorating state of the fight, getting the gist of the ship's condition and the “butcher's bill” of casualties. Then he left the quarterdeck for the cockpit.33 It took unquestioned bravery to face enemy fire, but for Hacker to go below and tell Barry what he had in mind took every speck of his courage.

Having stanched the bleeding, Kendall was applying a bandage to Barry's shoulder when Hacker approached. Barry shot a dark, quizzical look Hacker's way, then asked why the lieutenant was not on deck, directing the fight. Speaking fast, Hacker told him about “the shattered state of the sails and rigging, the number of killed and wounded, and the disadvantages under which they labored, for the want of wind.” Breathlessly laying out the facts as he saw them, Hacker asked—he was not fool enough to suggest—“if the colours should be struck.”34

Barry's reply was immediate and thundering. Struggling against Kendall's ministrations (and doubtless starting his shoulder bleeding again), Barry became a wounded lion. “No!” he roared. “If the ship can't be fought without me, I will be carried on deck.” He dismissed Hacker back to the fighting and began arguing sharply with Kendall about getting dressed, determined to return to the battle. To Hacker's credit, he left any resentment of Barry's tongue-lashing below. Bounding up the hatchway, he returned to his post and “Made known to the crew the determination of their great commander.” Informed of their captain's decision to keep fighting, the crew “one and all resolved to ‘stick by him.'”35

Now, even Nature seemed to respond to Barry's exhortations. With unannounced quietness, and ever so gently, the wind returned. Kessler forever remembered this instant as “a small breeze of wind happening.”36 Every sailor on deck could feel it on their sweat-stained cheeks. They breathed it into their lungs, and held it in for a second, then exhaled as they watched it slowly, surely, puff out their tattered sails. The combination of Barry's scalding Irish temper and the return of the wind unleashed the pure warrior in Hacker. Immediately, he bellowed orders as the ship responded to the long awaited, simple change in the weather—a soft breeze. The Alliance answered her helm, sailors manned the braces, and the battered frigate moved into a position that would allow her to finally fight back with all of her might.

After dispatching Hacker to his duties, Barry continued to insist on getting dressed and returning to the quarterdeck. Kendall, seeing that there was no chance in keeping him below, assisted him in getting shirt and coat over the right arm and around the left. The task of rerigging the captain coincided with the crew's getting the Alliance under way.37

Now, for the Alliances, the old adage “He that sails without oars stays on good terms with the wind” came true at last. The breeze touched British cheeks as well, but for Edwards and King, it carried defeat, not victory. Before they could try to sail or row out of range, the first broadside from the Alliance's starboard guns—fourteen 12-pounders—came smashing into the Atalanta.38 The proximity to the Alliance had been an advantage for Edwards's small 6-pounders when coupled with the Alliance's inability to move. Now such nearness was folly. Round shot shredded British rigging and further battered the Atalanta's masts, already damaged from the battle's opening broadside. Seconds later, the fourteen guns on Alliance's portside were loaded, primed, aimed, and fired at the Trepassey. One blistering salvo from the Alliance was enough for King. With his ship “Quite disabled,” he ordered his colors struck.39

Aboard Atalanta, Edwards was not yet inclined to surrender, and quickly reviewed his other options: continue the fight, or try to flee. Either action required getting his ship away from the Alliance. He decided to break off the engagement. But in his attempt to sail the Atalanta out of danger, the strain on her injured masts reached the breaking point. Edwards and his crew heard a sharp crack, then another. They knew at once what was coming next. Pulverized by the Alliance's guns, the fore and mizzen masts gave way. The Atalanta's crew scrambled in an effort to avoid the wood, canvas, and rigging crashing onto the deck. Meanwhile the Alliance was wearing again, her guns ready. On the uproll, Hacker cried, “Fire!” This last, raking broadside did the trick: “The Atalanta . . . was a wreck.” Reluctantly, Edwards, too, struck his colors.40

Barry was still struggling up the hatchway when all went silent above him.41 Then he heard another chorus of hoarse cheers, only this time they came from the Americans. After the second British ensign fluttered down, they left their posts, leaping into the shrouds and along the bulwarks, roaring in exhausted jubilation. Recognizing why his sailors were cheering, Barry allowed Kendall's assistants to change his course, and get him to his cabin.

The battle had lasted nearly four hours.42

A much relieved Hacker found Barry in his cabin and relayed the news of his victory. Barry gave orders that Kessler take the pinnace and bring the vanquished British commanders back to the Alliance to discuss terms. Kessler reached the Trepassey first. Finding Smyth dead, he proceeded to the Atalanta, where Edwards greeted him with the usual courtesies, then accompanied Kessler back to the Alliance. Edwards's pleasant demeanor, first exhibited when he engaged Barry in conversation before the first broadside, had cloaked any personal anxiety over the coming fight. Now it masked the disappointment he bore in surrendering two of His Majesty's vessels over to a rebel captain.43 The climb up the Alliance's gangplank must have been very steep for such a man.

Once at the gangway, Edwards presented Hacker with his sword, only to be told that the Alliance's captain was “confined in his cabin.” After a knock on the door, Edwards was admitted, where he found “Capt'n Barry then there seated in an Easy chair his wound dressed.” Again Edwards proffered his sword, this time to the correct officer. Using his right hand, Barry received it from Edwards, then “immediately returned [it] to him,” saying, “I return it to you Sir[.] You have merited it, and your King ought to give you a better Ship.” To Edwards's further surprise, Barry continued, “Here is my cabin at your service, use it as your own.” He then ordered that Lieutenant King also be brought aboard.44

While Kessler returned to the Trepassey to escort King, Edwards told Barry his reasons for taking on his frigate in battle. He was “confident that they would subdue the Alliance . . . when the disadvantages under which the Alliance labored are considered.” Barry, hurting as he was, must have suppressed a chuckle; had Edwards really “known all [the Alliance's] disadvantages”—Barry's woefully undermanned ship, the frigate's sad condition, and all those British prisoners—Edwards certainly “had more reason to “flatter [himself] with success” then he knew.45

Once King arrived, he and Edwards reported their casualties and crew sizes. The Atalanta had five killed and fifteen wounded of her 125; the Trepassey, including Captain Smyth, had six killed with ten wounded of eighty aboard.46 Barry did the arithmetic in his head. The captured crews put the number of his prisoners at over three hundred, far too great a number for the Alliance to hold, let alone feed.47 They would rekindle fears among his officers of another uprising. Both Edwards and King reviewed the condition of their injured vessels. Sailing both the Atalanta and Trepassey to an American harbor, even with the smallest of prize crews, would leave Alliance far too diminished in manpower. Barry came up with a solution to this logistical nightmare: if one of the British ships sailed back to St. John as a cartel with all of the captured British aboard, would the British admiral exchange a similar number of captured Americans? With the admiral in question being his uncle, it was an easy question for Edwards to answer. He assured Barry that a fair exchange would be carried out.48

By now it was “too late in the day to effect removal.”49 Barry sent a prizemaster and crew aboard each British ship, with orders to keep close by the Alliance overnight. Edwards and King were to stay aboard the Alliance, along with the other officers and British wounded.50 They were Barry's hostages, guaranteeing both his conditions for surrender and Edwards's word on prisoner exchange.51 Barry requested that Edwards and King address their crews regarding the terms, and they agreed. Borrowing Barry's speaking trumpet, Edwards spoke across the lapping water to his men, informing them of Barry's generous terms and that he had assured Barry of their “orderly behavior during the night.” King then did the same. Their orders had “the desired effect,” resulting in a peaceful night after this violent day.52

At sunup, the Atalanta's crew heard a familiar, cracking sound, as the mainmast snapped and fell on the deck, to be heaved over the side. Later that morning, Hacker updated Barry on the conditions of the three ships along with the latest casualty report. The Alliance, “shattered in the most shocking manner . . . wants new Masts, Yards, Sails and Rigging.”53 Her casualty list was five killed and twenty-four wounded. Three of them, including Pritchard, soon died of their wounds.54

Despite the Atalanta's condition, Hacker told Barry that she was a prize worth taking home. Not only was “she the larger of the two vessels,” but “her hull was sheathed in copper.” While Barry ordered “Jury Masts upon her,” different renovations were afoot aboard the Trepassey. Barry ordered her guns thrown overboard. Then, after her military stores were transferred to the Alliance, he placed her under command of her sailing master. The Trepassey was loaded with all of Barry's prisoners, save Edwards and the other officers, and sailed for Halifax that afternoon.55 Repairs on the other two ships took another day. Barry gave command of the Atalanta to Hezekiah Welch, with orders to sail to Boston, being “the Nearest and safest Port.” It was another day before the Alliance was seaworthy enough to sail. Barry was convinced that she would not make Philadelphia, being “In a Shattered Condition[,] very foul and hardly Men enough to work on Ship.”56 The wounded frigate “made all sail for Boston.”57

Patrick Fletcher, lucky enough to avoid both bad weather and British warships, arrived in Boston with the “Guernsey privateer” Mars on May 12.58 Assuming the same luck was with Barry, Fletcher reported that the Alliance, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Barry's prizes were not far behind. After three weeks passed, the Alliance was feared captured or lost—yet another tragedy for the American navy.59

On June 6, the Alliance, hardly recognizable from the trim, sharp frigate that departed in February, came up Nantasket Road, having eluded the British blockade off Cape Cod. With no spar of sufficient size to replace her main yard she sailed without one, her sails covered with countless patches.60 It had been sixty-nine days since she departed L'Orient.61 Crowds gathered along the waterfront, their jaws agape at the damage they saw to the frigate.

The Alliance's docking could not come soon enough for Kendall. Barry was an uncooperative patient whose “wound was considered in a dangerous state.” A crowd had already gathered along the wharf when the Alliance's gangplank was run out. Accompanied by Kendall, Barry was carried on a stretcher and “immediately landed,” then taken to a house along the waterfront. Once in his new surroundings, Pool and Kessler, both recovering from wounds, bivouacked in the house as well, and Barry put both to work. Sitting up in bed, with the Alliance's log at his side, he dictated three long letters to Pool: one to Congress and the Admiralty Board, another to the Eastern Navy Board, and one to Sarah. He recounted the details of his voyages to L'Orient and back to Boston. “I am amongst the wounded,” he reported, optimistically adding, “I shall be fit for duty before the Ship will be ready to Sail.” As with Franklin, he asked permission for “Sheathing the Ship with Copper.” Giving Kessler the letter to the Admiralty, along with a letter of safe conduct allowing him “to pass from hence to Philadelphia undeterred,” he dispatched him “express to Philad'a to [fetch] Mrs. Barry.”62

With Kendall's admonishment to remain in bed, all Barry could do was to wait for the arrival of his wife and his prizes. He heard that the “Snow with Sugars is in a Safe Port to the eastward,” with “the Atalanta [expected] in every hour.”63 His anticipation of her arrival and that of the Marquis proved futile. While rumors swirled regarding the fate of the Marquis, Barry soon learned of the bad luck that befell the Atalanta. She was only a day or so behind Alliance when, on June 7, “Being near Cape Cod,” she fell in with four ships from the British blockade “which retook the said sloop Atalanta, put a British officer & Seaman on board her & sent her safe into . . . Halifax.”64 The arrival in Boston of his prize the Adventure gave Barry some consolation.65

Barry displayed “high spirits” to his visitors, but his convalescence was long.66 The wound healed slowly; sundered bone, tendons, and ligaments would mend as best as Kendall's knowledge of eighteenth-century medicine permitted.67 Whereas tendons in the arms and legs could “be rejoined by relaxing the muscle and bringing the bones nearer” with a splint, the location of Barry's wound prevented such a remedy. Nor did his pain abate; to lessen it, Barry was given “one dram of bark every three hours,” provided his stomach could handle it.68 Weeks would pass before he was “in a fair way of recovery.”69

While he recovered, news of his voyages and adventures appeared in Boston's Continental Journal, and then spread throughout the United States and across the Atlantic. The American press praised Barry's courage and leadership, while reassuring readers that he was recovering from his wound; British papers, of course, emphasized Edwards's gallantry. By mid-June Kessler reached Philadelphia. After giving a full narrative to the local press of the Alliance's triumphs over every adversity, and praising his captain's “unconquerable firmness and intrepidity,” he escorted Sarah to Boston.70

Congressmen and other dignitaries extolled Barry's success (although one dour politician grumbled that the Alliance “was fortunate in capturing prizes but brought no Stores”).71 The rest of Congress was jubilant and laudatory, not only for his victory and captures but for his rescue of the neutral Venetian merchantman Buona Compagnia. They quickly passed a resolution applauding his “utmost respect to the rights of neutral commerce,” and sent a copy to him that same day, along with a letter from the Admiralty commending his actions and expressing concern “that you was so ill of your wound.”72 Along with the narrative of his battle, the Buona Compagnia affair made the papers, eventually reaching Franklin in Paris.73

Barry also received a letter from John Brown, writing both as Admiralty Secretary and as his friend. While Barry was grateful for Brown's congratulations and “wish that your wound may be soon healed—that the use of your Arm may be restored and only an honorary Scar left behind,” he was more pleased to read that “We have too directed that the Alliance should be sheathed with Copper,” provided that there was “any person in Boston who knows how to put it on.”74 Much to Barry's delight, James Warren began “Entring on that business.”75