The West End of London is the capital’s entertainment district. And while it could be suggested that entertainment aplenty can be had from royal-watching, what we mean is that this is the part of town where we come to enjoy ourselves. And as we have seen, some royals can enjoy themselves more than others.

Which brings us quite naturally to King Charles II. King Charles II loved the theatre… by which we mean he loved actresses.

Elsewhere in this book we have discussed royal pub names and (ahem) royal favourites. Here in the West End we can bring those two factors together – twice – in the shape of Nell Gwynne.

The pub sign on this hidden hostelry, tucked no more than a dozen paces off the beaten track but still with a delicious, clandestine feel, features Nell in all her, er, glory. The sign is based on a work by Dutch Golden Age painter Simon Pietersz Verelst (he also painted Prince Rupert of the Rhine, see Chapter 8) – although in the pub sign version we seem to be treated to considerably less of La Gwynne’s left nipple than in the original.

Doesn’t welcome walking tours even when quiet, but worth a quick look nonetheless. The pub can be glimpsed in Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972) back when the district was in its fruit and veg market heyday.

It’s probably too late now to reclaim top billing for the artistic gifts of Nell Gwynne over her sexual reputation, but I feel it’s the decent thing to keep trying.

In the ‘new’ theatre, brought back to life after the restoration of the monarchy, women played female roles for the first time – young boys had played them hitherto. Gwynne’s particular talent lay in playing the female half of the ‘gay couple’, the male of whom would display rakish tendencies, with the woman protesting her virtue too much. These bawdy, broad restoration comedies still bring the house down in the 21st Century, and Gwynne was described by writer Elizabeth Howe as ‘the most famous Restoration actress of all time, possessed of an extraordinary comic talent’ in her book The First English Actresses.

Gwynne’s theatrical career began as an orange seller – the fruit with which she is so associated in the popular imagination. The orange sellers would, of course, sell oranges to the theatregoers but also relay messages backstage to the actresses who may have caught the eye of the gentlemen (I use the term advisedly) in the auditorium.

Gwynne gave birth to two sons, Charles (1670) and James (1671), fathered by King Charles II. James died aged ten. Charles became the first Duke of St Albans. It is said that this latter title was only coined to stop Nell referring to the child as ‘the Little Bastard’ in the presence of the King. ‘I have nothing else to call him by!’ she would protest. Rather than chanting ‘sticks and stones’ at his disgruntled mistress, the King created a dukedom.

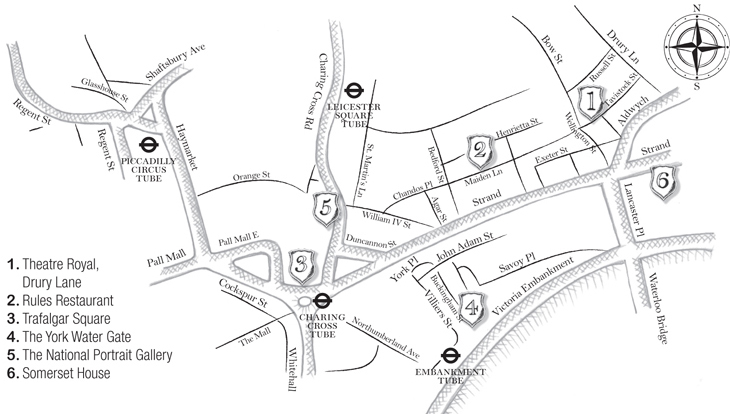

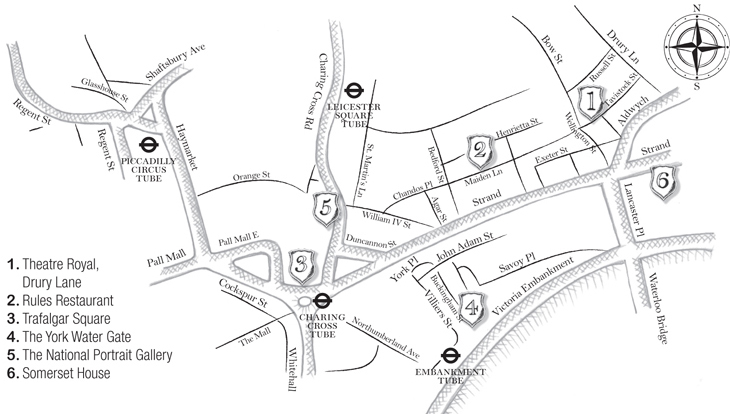

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (actually in Catherine Street) has occupied this spot since 1663 when King Charles II granted one Thomas Killigrew permission to stage ‘legitimate drama’.

The current building is the fourth such theatre on the site and dates from 1812 (with the interior renovated in 1922 into the opulent auditorium we enjoy today). Previous Theatre Royals had burned down in 1672, been demolished in 1791, and burned down again in 1809.

‘Legitimate drama’ is seldom the order of the day at the Theatre Royal these days. Straight plays have taken something of a back seat to musicals here since the Second World War, from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I to the musical of Mel Brooks’s The Producers.

My Fair Lady, book by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe, enjoyed its London premiere here in 1958, running for 2,281 performances. A musical version of Shaw’s Pygmalion, it starred Rex Harrison as Professor Higgins.

Harrison is the subject of one of the more persistent theatrical myths, which relates that he is the illegitimate son of King Edward VII. The musical features a famous scene at Ascot racecourse which, in the film (also starring Harrison) is costumed by Cecil Beaton as ‘Black Ascot’ – the famous Derby race meeting held in the wake of the death of King Edward VII in 1910, in which racegoers dressed in the colours of mourning.

TEN WEST END THEATRES WITH ROYAL CONNECTIONS

Prince of Wales Theatre

Coventry Street, W1D 6AS. Tube: Piccadilly Circus

Built in 1884 (the version we see today dates from 1937) and named after the future King Edward VII. In 1963, The Beatles played the Royal Variety Performance here, in the presence of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. John Lennon’s exhortation that those in ‘the cheap seats, clap your hands; the rest of you can just rattle your jewellery’ was received in the spirit of impish humour rather than sedition. Backstage, legend has it, in the royal line-up, the Queen Mother asked where the group were playing next. When informed that The Fabs’ next gig was to be Slough, she is said to have replied, ‘Oh, that’s near us,’ a reference to Windsor Castle’s proximity.

The London Palladium

Argyle Street, W1F 7TF. Tube: Oxford Circus

Widely regarded to be the pinnacle of British show business, it was here on 3 November 1952 that Queen Elizabeth II attended her first Royal Variety Performance with the Duke of Edinburgh. The bill included Tony Hancock and Norman Wisdom. It was on the way to the Royal Variety Performance in late 2010 that demonstrators protesting against student fees assailed the Rolls-Royce Phantom VI carrying the Princes of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall.

The Palace Theatre

Shaftesbury Avenue, W1D 8AY. Tube: Leicester Square

As its scale would suggest, this grand Victorian theatre was originally intended to be an opera house. The venue of the first Royal Variety Performance in 1912 in the presence of HRH King George V and Queen Mary. They were entertained by George Robey (‘The Prime Minister of Mirth’) and Harry Lauder.

Victoria Palace Theatre

Victoria Street, SW1E 5EA. Tube: Victoria

Designed by Frank Matcham, the Victoria Palace saw the original production of Me and My Girl open in 1937. When King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended, it was noted that the royal couple joined in on the ‘Oi!’ responses during the show’s most famous number ‘The Lambeth Walk’, a tune described by the Nazis as ‘Jewish mischief and animalistic hopping’.

The Empire

Leicester Square, WC2H 7NA. Tube: Leicester Square

Opened as a theatre in 1884, the Empire began showing films by the Lumière brothers in 1896. The first Royal Command Film Performance was shown here in 1946 (see Chapter 3).

The Prince Edward Theatre

Old Compton Street, W1D 4HS. Tube: Leicester Square/Tottenham Court Road

Built in 1930 and named after the then Prince Edward, Prince of Wales, who would become (albeit briefly and without coronation) King Edward VIII.

Duke of York’s Theatre

St Martin’s Lane, WC2N 4BG. Tube: Leicester Square

Opened as the Trafalgar Theatre, renamed in 1895 after the man who would become King George V.

Playhouse Theatre

Northumberland Avenue, WC2N 5DE. Tube: Charing Cross

Snoo Wilson’s play HRH, directed by Simon Callow, opened here on 2 September 1997. Its theme was the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the abdicated King Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson. In the immediate aftermath of the death of Diana, Princess of Wales it was harshly reviewed as anti-royal. The Playhouse was also home to The Goon Show, the BBC radio comedy so beloved of Prince Charles. Who else but Spike Milligan, the creative genius at the heart of the team, would be allowed to call the Prince of Wales a ‘Little grovelling bastard’ when HRH paid Spike a glowing tribute at an award ceremony?

The London Coliseum

St Martin’s Lane, WC2N 4ES. Tube: Leicester Square/Charing Cross

Completed in 1902, the London Coliseum is still the West End’s largest theatre with 2,359 seats. It had all sorts of advanced technical wizardry, including London’s very first revolving stage to aid the speed at which acts could follow on from one another, and the unique ‘King’s Car’ described in the programme thus…

‘Immediately upon entering the theatre, the Royal Party will step into a richly furnished lounge which, at a signal, will move softly along a track formed in the floor, and into a large foyer which contains the entrance to the Royal Box. The King’s Car remains at the entrance to the box and serves as an ante-room during the performance.’

It all sounds wonderfully sophisticated. However…

The King’s Car was only used once, when King Edward VII was treated to its luxuries. All went well until the lever was pulled for the car to move and the fuse blew with a bang and the car refused to budge an inch. Edward emerged roaring with laughter and walked to his seat in the royal box.

The Vaudeville Theatre

Strand, WC2R 0NH. Tube: Charing Cross

The stage door – and royal entrance – is situated on Maiden Lane, on the estate of the Duke of Bedford, was once gated at one end with a statue of the Virgin Mary at the other. Queen Victoria found this most inconvenient for her driver when trying to turn her coach and requested of Bedford that the gate be removed.

Maiden Lane is home to London’s oldest restaurant, Rules, established in 1798 and a favoured haunt of naughty old King Ted no. 7 and his – here we go again – great favourites, a series of women referred to by his wife Queen Alexandra as ‘the Horizontals’.

Rules specialises in traditional English fayre and in the 19th Century boasted the most exclusive ‘table for two’ in town. Behind the first-floor lattice window on the right of the main door was where the Prince of Wales, future King Edward VII, would secretly wine and dine his mistress the ravishing actress Lillie Langtry. There was even a secret side door created so that the couple could come and go undetected by other diners.

When Edward VII had her presented to the royal court and to his mother Queen Victoria, Langtry rather cheekily wore a headdress with three tall ostrich plumes, daringly mimicking the Prince of Wales’s crest. During his time as PoW, it is said that Queen Victoria feared for the continuity of the monarchy, such was her heir’s free-and-easy behaviour. Even at Edward’s coronation, there were seats set aside for three of his mistresses in the balcony or clerestory of the Abbey. Some commented on this, calling the balcony Edward’s Loose Box.

The royal history of Trafalgar Square goes back to the reign of King Edward I when what is now the northern side of the square was used as a place to keep the royal hawks and horses – the royal mews.

And even in the 21st Century, Trafalgar Square is immediately readable as a clear statement of imperial intent. Lions and heroes and kings, oh my! (to borrow from The Wizard of Oz).

The bronze lions are the work of Sir Edwin Landseer, an artist beloved of Queen Victoria herself and from whom she often commissioned portraits of her family and pets. Above the lions, Nelson sits atop his famous column, one of very few contexts where a ‘commoner’ is elevated above the monarchy.

Some 176 feet below and behind the great naval hero, to his left shoulder we find an equestrian statue of King George IV. The great Francis Chantrey brings us the handsome figure of ‘Prinny’ on horseback. In life, such a horse would have required a robust constitution given that the king often had trouble passing a pie.

To the west of the king on horseback is the square’s most famous, most talked-about, most controversial plinth – the fourth, or the ‘empty’ plinth. Originally, the plinth was reserved for an equestrian statue of King William IV, but funding for the project was found to be insufficient on the King’s death.

Over the years a number of candidates have been proposed for the plinth. Diana, Princess of Wales was one such suggestion; Nelson Mandela another, given the proximity of South Africa house and the anti-apartheid demonstrations that took place in the square during the 1980s. But in 2008 it was reported that the plinth was reserved for another equestrian statue – the design is, after all, symmetrical, and a second equestrian statue would balance the square perfectly. The subject of the statue, the report said, was to be Queen Elizabeth II and work would commence upon her death. At the time, a GLA spokesperson told the Daily Mail: ‘We will not enter into speculation about the long-term future of the fourth plinth, but the GLA is concerned with managing the successful rolling programme of contemporary art.’

Since 2008, the story of the Queen’s statue has disappeared and the rolling programme of contemporary art has taken up residence on the fourth plinth. Sir Keith Park, the man charged with the air defence of London during the war, was commemorated here before being moved to a permanent berth outside the Athenaeum Club. And, in 2009, Anthony Gormley’s Fourth Plinth project offered everyone the opportunity to be king for a day by allowing members of the public to ‘book in’ to a slot to act as a living statue.

A final kingly statue, however, can be found in Trafalgar Square. King James II in Roman garb can be found just outside the western end of the portico of the National Gallery. The last Catholic king of England, James II’s belief in the Divine Right of Kings, the same business that got his old man Charles I into such hot water, saw him emerge as a threat to the established order. When his son-in-law William landed an invading army from the Netherlands, James fled into exile in France and William was crowned as the third king of that name, with his wife, James’s daughter, as Queen Mary II. With the Jacobite forces defeated at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, James lived out his days as a pretender to the throne in exile.

The current positioning of his statue (credited to Grinling Gibbons) is the fourth such berth it has occupied in London, having also stood in Whitehall and St James’s Park. One can’t help wondering that if the Queen Elizabeth equestrian statue business turns out to be true, then will it be appropriate to have King James II seemingly tiptoeing up behind the Defender of the Faith in Trafalgar Square?

At the southernmost side of the square, we find another equestrian statue, that of Jimmy II’s dear old dad, King Charles I. At its, erm, hindquarters, a plaque set in the flagstones attests that this is the dead centre of London. This plaque was required when civil servants were given an extra living allowance to account for the additional expense of living in a six-mile radius of central London. With this plaque, there was no fiddling of the expenses.

The statue of King Charles is the oldest thing on display in the square, dating from 1633, and hidden at the end of the English Civil War. During the Second World War the statue was taken down and put in a safe place. Presumably the removal of the king’s head with an axe in 1649 was ignominious enough, and letting his head get blown off all over again by the Luftwaffe would just have added insult to injury.

The statue, in turn, stands on the spot where the Eleanor Cross once stood – the replica monument, now called Charing Cross, stands just a few hundred yards to the east of the original site.

The Eleanor Crosses were erected on the say-so of King Edward I upon the death of his beloved Queen Eleanor, who died in Northamptonshire in 1290. Twelve crosses were erected to mark the route of the funeral procession to the Abbey. Three survive – one at Waltham Cross, another (the best preserved original) at Geddington, and one in Northampton. But the most famous is the 19th-century version at Charing Cross.

Charing was named after the ancient village that once stood at the bend in the River Thames (‘charing’ is old Saxon for bend or turn in the river). The cross that can be seen today stands before the Charing Cross Hotel, just to the east of Trafalgar Square at the start of the Strand. Resembling nothing less than the spire of some vast, underground cathedral, it dates from 1865 and was commissioned by the South Eastern Railway – the artist was Edward Middleton Barry – to act as the centerpiece of the forecourt at their grand new railway terminus.

The River Thames, as well as being a healthier and far less busy waterway today, is also a lot less wide, having been embanked in the 1860s (see Chapter 7). Its former width at Charing Cross can be gauged by the position of the York Water Gate, attributed to Inigo Jones, a Grade I listed structure, which was once the riverside entrance to the home of the Bishop of York (the site had been the property of the Bishops of Norwich until King Henry VIII’s time).

In the 1620s it became the London home of George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham – nearby Villiers and Buckingham Streets are named in his memory. Villiers was the great favourite of King James I (and VI). His portrait can be found back in Trafalgar Square at the National Portrait Gallery. The picture captures his favourite feature – his lovely, long legs – in all their glory.

If you’re on a whistle-stop tour, these are the ones to see.

A portrait that proves the dictum: the victors write history. The crookback villain of Shakespeare’s play is here captured looking a rather worried man. Milky, almost. That he plays with his gold ring is no doubt to signal to us, if we had forgotten, of his wealth and power. The effect, however, is more that of a man who can’t remember if he’s switched the gas off before leaving the house. An illuminating look behind the myth.

Master John seems to be aiming for demure… but the eyes have steel in them, and there’s determination in those thin lips. Queen Mary’s nickname to history? Bloody Mary.

Serene, despite the elements gathering about her, clad in virginal white and standing square in the heart of her realm, this great hagiographic portrait of Good Queen Bess was commissioned from Gheeraerts by Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley. The Queen’s great favourite Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex was also one of Gheeraerts’ subjects.

King James cuts a melancholy monarch in this portrait, despite his finery, his regal red robes. Is it the strain of dealing with Parliament showing in his sad eyes? Or is it that they’ve positioned him for posterity in such a pose that he can’t see the well-turned ankle of his great favourite the Duke of Buckingham (see below)?

Ten years on from the portrait of his father, Mytens again brings out the melancholy in the royal gaze. But here, hindsight gives the look a tone of resignation rather than sadness. The trappings of monarchy are all around him – the crown to his right hand, opulent red drapes adorn his room. Do his blue clothes allude to the Virgin Mary and the Divine Right of Kings? Similarly, the glimpse of the blue sky in the background: his heaven-sent right to be absolute monarch?

This king has a look of a man who labours under an almost pathological inability to deny himself even the smallest pleasure. And by 1680, when the King was 50 years of age, it was starting to show. And bear in mind that the artist may have been, er, overlooking certain signs of overindulgence. The double chin is creeping in – and if it’s creeping in in an oil painting, what was it doing in life? If I were in an uncharitable mood I might even go so far as to say he looks seedy. A vivid study in overindulgence.

Art and artists have long been kind to our dear royals. And this is no more in evidence than in this portrait of Queen Anne. By all accounts a larger lady – buried, famously, in an almost cube-shaped coffin, as we have seen – Dahl’s portrait captures her as such. But, as with King Charles above, if Dahl is aiming for somewhere between big-boned and Rubenesque, what would a camera have caught had such a thing been around?

The storm clouds of war gather all around, but all they can do is tousle the King’s hair into a coiffure that would be the envy of any boyband. Again, this heroic figure of a fellow may not necessarily be 100% accurate, particularly in terms of girth. (We are reminded of Beau Brummell’s archly cutting remark, ‘Who’s your fat friend?’ aimed at George when he was Prince of Wales.) It has been suggested that Prinny was feeling a little left out of the military shenanigans in the continental Europe of the day, and wanted to play at soldiers with the best of ’em – hence the costume and setting of this portrait.

An actual sailor this time – Sailor Bill was one of his nicknames – King William IV looks perfectly at home among the swirl of smoke and the ensign of the navy, his cheeks reddened not from overindulgence (see Charles, above) but from the exertions of war.

Sir George Hayter catches both a young queen and the 21st-century gallery-goer off guard. Where we often expect the older version of the popular imagination, here we have the young queen who took the throne at the age of just 18. Like the portrait of King Richard III (above) it challenges the popular perception of the monarch and encourages the modern onlooker to consider the Queen from a different angle.

TEN ROYAL CAMEO ROLES, BADDIES, SUPPORTERS AND LOVERS IN THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

If you’ve abandoned your whistle-stop tour because you’ve fallen in love with the National Portrait Gallery and are going to throw away your tickets to We Will Rock You and stay and enjoy the paintings instead, then these are the next ten to see…*

Thomas Cranmer by Gerlach Flicke, 1545

Instrumental in Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, Cranmer’s dark, wide eyes stare into the middle distance as if in contemplation of the scriptures – a bible is open in his hands and important-looking documents lie nearby.

Flora Macdonald by Richard Wilson, 1747

Again an illuminating reminder that there are two sides to every story. Those who are over-fond of tales of Scottish heroism being peopled by small Australian actors with blue faces need only look at this portrait: calm, even serene, this is a woman whose self-possesion and sense of duty needs no Hollywood makeover

Bonnie Prince Charlie by Louis Gabriel Blanchet, 1738

Roguishly referred to by one of my Scots London Walks colleagues as King Charles III, he is captured here in another portrait that may cause great surprise to those of you who have seen Braveheart too often. Bewigged, rouged of cheek, striking a pose that suggests nothing less than a man who is just about to bust a few moves on Strictly Come Dancing… And small, too. Perhaps even smaller than diminutive Australian actor Mel Gibson, who donned the blue face paint to play William Wallace, his spiritual antecedent, in the aforementioned Braveheart.

Prince Rupert, attributed to Gerrit van Honthorst, c1641

He still looks like an early 1970s rock musician. Very soulful eyes.

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, attributed to William Larkin, c1616

It’s all in the legs. Villiers believed himself to be in possession of the finest and most attractive pins in the kingdom.

Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor by Gerald Leslie Brockhurst, 1939

A love story to beat all others? A priggish fop with a bullyish penchant for the wives of other men? The story of Edward and Mrs Simpson still has the power to enthral. And here at the National Portrait Gallery there are a number of photographic studies of the wicked woman in question which will also do just that. Not a conventional beauty, but certainly strikingly handsome. We’ve been combing through her photographs now for generations, looking for clues as to why the King would give it all up. Richard Avedon’s photograph of the Duchess with her beloved Edward from 1957 has the melancholy air of an old-time vaudeville act only half remembered by their once-adoring public. Cecil Beaton, 20 years earlier, captures more of a star-crossed lovers element to the couple. Away from her famous husband, in Gerald Brockhurst’s oil on canvas from 1939, she seems angular, feline and beguiling indeed. Which is the real Duchess? I suspect that all of them are, in their own way.

Oliver Cromwell by Robert Walker, c1649

Cor, ‘e’s like the spectre at the feast, ain’t ‘e just? History, again, is painted by the victors, as this perfectly reasonable figure of middle England looks us clear in the eye with all the assurance of one with God on his side. Not smiling, suffice to say.

Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), Duchess of Cleveland with her son, Charles Fitzroy (as Madonna and Child) by Sir Peter Lely, 1664

‘Mistress of King Charles II’ is hardly an elite club – but this portrait perhaps tells the tale of the woman whose title of ‘Mistress of KCII’ is often prefixed with ‘the Most Important’, ‘the Most Beautiful’ or ‘the Most Influential’. The look in her eye, as she brandishes the king’s illegitimate son like a trophy, is certainly one of the cat who has got the cream. Gave the King five illegitimate children and picked up the nickname ‘the Uncrowned Queen’ along the way. On the wedding day of Charles and Catherine of Braganza, she hung her undergarments in the palace grounds for all to see. Samuel Pepys, never far from getting overheated on such matters, gives us this account:

‘In the Privy Gardens saw the linen petticoats of my Lady Castlemayne laced with the richest lace at the bottom, that I ever saw, and it did me good to look upon them.’

Maria Fitzherbert by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1786–1788

‘Morganatic’ is one of those words that royal experts tend to brandish like peacock feathers to signify that they are not merely watching a good old soap opera along with the rest of us. Defined as ‘of or denoting a marriage in which neither the spouse of lower rank nor any children have any claim to the possessions or title of the spouse of higher rank’ it is a term that always crops up in conjunction with Maria Fitzherbert. One of the great beauties of the age, her morganatic marriage to King George IV went unrecognised as she was Catholic, and she occupied the status of mistress in the eyes of the law when the King married Caroline of Brunswick.

Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth by Pierre Mignard, 1682

Mistress of… guess who? Her position as mistress was encouraged by the French government as a, ‘ow you say, tool of diplomacy. She is pictured with a black slave girl whose presence serves to remind us of the Duchess’s status.

The Somerset House we know and love today – Sir William Chambers’ masterpiece from the late 18th Century with Victorian additions – has both hidden and housed episodes of great rebellion in our royal story.

The current structure, begun in 1776, occupies a site upon which a royal residence had stood for more than two centuries prior to this. The Duke of Somerset, Edward VI’s Lord Protector, built an imposing palace here; before becoming Queen Elizabeth I, plain old Princess Elizabeth used the palace.

In the 17th Century the palace was used by the queens of King James I (indeed, his bride, Anne of Denmark, gave rise to the palace being renamed Denmark House) and Charles I and II. It was the religious practices of Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II, that saw the place gain a reputation as a hotbed of Catholic conspiracy. This conspiracy was central to Titus Oates’s fabricated Popish Plot of 1678.

NINE ROYAL FINGERPRINTS ON THE MODERN-DAY STREETS OF THE WEST END

Orange Street, WC2

A slightly more oblique royal reference than the one most apparent – William of Orange. The orange in question here is the principal colour of the coat of arms of the Duke of Monmouth, eldest illegitimate son of King Charles II. This southern extremity of his land – his palace helped form what is now Soho Square – was where he kept his stables.

Villiers Street

Named after George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham.

Charles II Street

Completed in 1689 on land developed by the Earl of St Albans, Henry Jermyn (the founding father of modern St James’s). It was known as plain old Charles Street until as recently as 1939.

Kingsway

Named after King Edward VII, this long, wide street, in tandem with Aldwych, cleared away many a music hall, drinking den and house of ill repute from the London map in the early 20th Century. Given the nature of the goings-on here in former days, some have commented on the ironic nature of naming the new road after our good-time king.

Regent Street

One of the most famous shopping streets in all of London bends its elegant progress from Piccadilly to All Souls Church. It is still associated with the great John Nash, although the only building of his that survives is the aforementioned church. Every building is preserved as a listed building of one grade or another and the street is named after the Prince Regent, later King George IV.

Essex Street, WC2

Marks the location of a riverside mansion, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I.

Burleigh Street, WC2

The location of another of Elizabeth I’s favourite mansions.

William IV Street, WC2

A street the colour of public school refectory custard built in the reign of the king after which it is named. Once home to the Charing Cross Hospital, the Metropolitan Police now occupy the building.

Hanover Square, W1

Named after the Royal House of Hanover 1714–1901; first monarch King George I, last monarch Queen Victoria.

Savoy Place

The Savoy Hotel – the first hotel to be lit throughout by electricity – could count King Edward VII among its guests. Its name goes a long way further back, however, than the foundation of the hotel in 1889. The Savoy Palace that stood here until 1381 – when it was destroyed in the Peasants’ Revolt (see Chapter 6) – was considered to be the grandest of all medieval residences. In the 14th Century it was the property of John of Gaunt, uncle of Richard II.

A NICE SIT DOWN AND A CUP OF TEA

Finding somewhere to sit down and have a cup of something in the West End is every bit as simple as digging up traces of the monarchy in North London was tough (see Chapter 4).

Of our three categories, well, it’s safe to say that they are all pretty much on the main drag – it’s just that some of them are more prominent than others.

On the main drag

The Sherlock Holmes Pub

10–11 Northumberland Avenue, WC2N 5DB. Tube: Embankment

This pub is one of the most touristy in town and is always very busy. But then show me a pub that’s quiet every night in central London and I’ll show you a pub that will soon be turned into a Starbucks. Busy pubs are busy for a reason and this one has the wonderfully eccentric Sherlock Holmes exhibit upstairs, as well as fine fish and chips and sundry other English fare in the restaurant.

As you leave the restaurant, go straight out of the door at the bottom of the stairs. Look up, above the anonymous fire exit doors immediately before you, and you’ll see some eastern-flavoured tilework. This is the former entrance of the Northumberland Avenue Turkish bath – where Holmes and Watson discreetly discuss the details of their Illustrious Client (mentioned earlier in Chapter 8). In the upstairs restaurant itself you can find the aforementioned Sherlock Holmes exhibit – a ‘lifesize model’ of the great detective’s study. Look closely and you will see the initials VR shot into the wall with bullets. Holmes, great establishment man that he is, has paid tribute to the monarch while indulging in a spot of shooting practice.

Great detective, loyal monarchist, lousy next-door neighbour.

Something a little stronger, perhaps?

Gordon’s Wine Bar

47 Villiers Street, WC2N 6NE. Tube: Embankment

Gordon’s Wine Bar is a London legend. This cellar bar, with its faux-dingy décor and false cobwebs, was once described as resembling the venue at which Miss Havisham held her hen night. The walls are adorned with old newspaper cuttings and front pages, many of them featuring big royal events. Founded in 1890, it is the oldest wine bar in London.

Sssshhh. It’s a secret

The Café in the Crypt

St Martin-in-the-Fields, Trafalgar Square, WC2N 4JJ. Tube: Charing Cross/Leicester Square

Okay, it’s hardly a secret: the Café in the Crypt is a beloved rest-and-be-thankful of countless Londoners. But it is a hidden gem in the respect that it is the café beneath a wondrous classical church by James Gibbs. A great, affordable menu, wonderful nooks and corners in which to sit down and have a read, masses of London Walks leaflets to grab on the way in/out. And you’re in and around the spot where King Edward I kept his stables (see here).

*8The collection at the NPG is rotated regularly and some works may not be on display when you visit. If this is the case, you can make use of the NPG’s wonderful computerised archive, Portrait Explorer, on the ground-floor mezzanine (nice, comfy chairs, too!) and browse the portraits that the gallery lacks space to have on view.