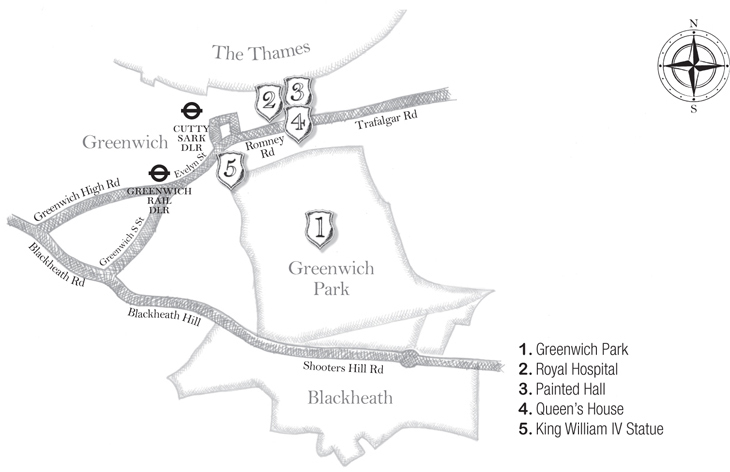

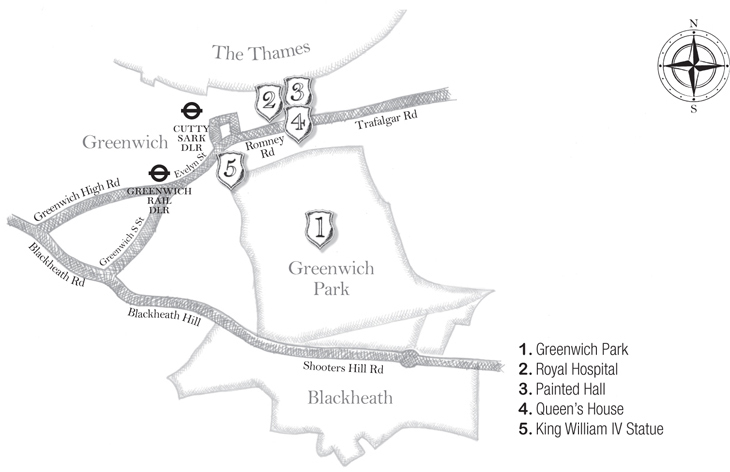

First, a quick word about getting to Greenwich. Rail links are plentiful and easy to follow. The good folk of the Docklands Light Railway have even named one of their stations ‘Cutty Sark for Maritime Greenwich’ to make it easier.

But if you want to hit this old royal stamping ground in true regal style, the best way to do so is by boat.

Okay, the eastbound boats from Westminster and Tower piers may lack the decadence and sheer theatricality of a Tudor royal barge (no offence to the boat operators!) but they will provide the easiest way to follow the common royal route that was used right up until the middle of the 19th Century. King Henry VIII was born at Greenwich and would have used the water regularly to get along to Hampton Court way out west.

Thames Clippers run regular services on the Thames – with seasonal variations – and their website is at www.thamesclippers.com.

A boat trip along to Greenwich from Tower Hill is also a feature of London Walks’ regular Greenwich tours.

In all of London, Greenwich provides perhaps the most harmonious blend of royal past and royal present. Its roots as a royal playground stretch back to the 1400s, but in this glorious corner of South-east London, history is far from hidden. The Royal Hospital, the Royal Observatory and the Royal Park all provide an impressive backdrop to a vibrant neighbourhood. To describe present-day Greenwich without using the word ‘splendour’ is as tall an order as describing a spiral staircase without using swirly hand gestures.

When it comes to Greenwich, or indeed the Royal Family, ‘new’ is seldom a word we throw around. Yet that’s precisely what the old girl Greenwich is: the newest Royal Borough of London. The honour has been bestowed to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee of HM Queen Elizabeth II in 2012.

Greenwich is, of course, far from new. Its royal links go back around 600 years in this village. Not quite as old as the Abbey (see Chapter 7) of course, nor quite as old as time, even if time as we know it is as old as Greenwich.

In terms of royal stars, all the big-hitters are here: King Henry VIII, King Charles II, Liz I and more. And the walk-on parts are pretty impressive, too: Nelson, Captain Cook, Christopher Wren are just the tip of the imperial iceberg. Factor in location – on the Thames, the gateway to the world and the path to empire building. Greenwich is where the land meets the water and its story is that of an empire that felt confident it had already tamed the former, and was keen to rule the latter in order to conquer more.

That Greenwich became a Royal Borough in name in the year 2012 is a needless appellation for many. Greenwich has always been a royal borough, ever since King Henry VI’s Lord Protector the Duke of Gloucester enclosed the 200-acre park here and commenced the building of an impressive palace in 1422.

Hitherto it had been a ‘solitary wilderness’, in the words of Geoffrey Chaucer. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester – brother of Henry V – was very much a man of parts – military hero, skilled diplomat and academic. His book collection formed the basis of the hallowed Bodleian Library in Oxford.

He lacked the smarts, however, to notice that his wife Eleanor of Cobham got up everyone’s noses with her fondness for astrology and potions, and when her astrologers predicted ill health for King Henry VI (Gloucester’s nephew), the writing was on the wall. The astrologers were arrested on a charge of treasonable necromancy – not an offence one hears often down the Old Bailey these days – and executed. Eleanor was made to do public penance and divorce her husband, and was sent to prison for life. And how, pray, had King Henry VI found out that Eleanor’s astrologers were lying? Why, he asked his own astrologers, of course. It’s like a scene straight out of Blackadder.

Gloucester himself was had up for treason in 1477 but died three days after his arrest. Some say he was poisoned; others that he died of a stroke. I’m going to counsel that we err on the side of the stroke: we don’t have to go looking for lurid deaths and conspiracy theories, given the larger-than-life figure who is looming just down the red carpet of our narrative…

Gloucester’s Greenwich Palace, by then named Bella Court, became the possession of King Henry VI, and Henry’s wife Margaret of Anjou had the ol’ place beautified with terracotta tiles, the great luxury of glass in windows, a treasury and landing stage for sailing vessels. She renamed it Placentia, meaning Palace of Pleasures.

Which brings us to that aforementioned larger-than-life figure seldom noted for his ability to deny himself any Placentia whatsoever…

The popular image of King Henry VIII – that of the, er, big-boned wife decapitator – will probably never be dislodged from the collective imagination. This despite the best efforts of racy TV dramas with lantern-jawed and ripe young actors in billowing shirts open to the waist (be still, my beating heart).

The truth of the matter exists somewhere between the two. Much as Queen Victoria wasn’t always aged and tough to tickle (see Chapter 1), it follows that King Henry VIII wasn’t always such a blimp. In his younger days the American-English expression ‘jock’ would very much fit the bill: sporty, active, competitive in the extreme.

Jousting. Shields. Tents. Heraldry. Those tall, pointy hats with the damask veil fluttering like a flag. Does anything say ‘yore’ like a tournament?

As a young man, Henry revelled in the thrill of the tournament. And his opponents were not necessarily always other sportsmen. Indeed, it was at just such a tournament at Greenwich in 1536 that his wife Anne Boleyn was arrested and taken to the Tower on a number of trumped-up charges so that Hank might move on and get down to the breath of fresh heir that was Jane Seymour.

In a brutal belt-and-braces approach, Henry had five men – including Anne Boleyn’s own brother – arrested on charges of adultery with the Queen, incest and high treason. Anne and the five men were found guilty and duly executed. This gory fate befell them despite the fact that, for some observers and many historians, the cases against them didn’t quite come off. Unlike Anne Boleyn’s head (see Chapter 9).

Greenwich runs through the story of Henry VIII’s life like veins through a slab of marble. He loved hawking and hunting in the park against the backdrop of ships bringing silk and gold and spices up the Thames.

It is thanks to Henry that we know the place as Maritime Greenwich (more of that anon), but it could just as easily be dubbed, in Henry’s case, Marital Greenwich. We are so distracted by the catalogue of goings in his married life that sometimes we forget about the comings.

Henry was married thrice at Greenwich – first to Catherine of Aragon, his brother Arthur’s widow. He later married Anne Boleyn here in secret in 1533. Oh, and Anne of Cleves, too. Are you keeping up? I’ll put it in a handy list to go with the famous one about the six wives, the one that goes:

Divorced – Beheaded – Died

Divorced – Beheaded – Survived

In the same vein, the wedding venues go:

Greenwich – Greenwich – Whitehall

Greenwich – Oatlands Palace – Hampton Court

Was he giving Greenwich just one last chance before moving on? The marriage to Anne of Cleves was doomed from the start. Henry had never before met his bride and wasn’t over-smitten by her looks (see quote 4, below).

SIX QUOTES FROM KING HENRY VIII ON HIS SIX WIVES

1) Catherine of Aragon: ‘[My marriage is] blighted in the eyes of God.’

2) Anne Boleyn: ‘… to wish myself (specially an evening) in my sweetheart’s arms, whose pretty ducks* I trust shortly to kiss.’

* Ducks = breasts

3) Jane Seymour: This from his last will and testament: ‘… that the bones and body of his true and loving wife, queen Jane, be placed in his tomb.’

4) Anne of Cleves: ‘The ugliest woman in Christendom.’

5) Katherine Howard: ‘My rose without a thorn.’

6) Catherine Parr: ‘Most dearly and most entirely beloved wife.’

Both of his daughters – Queen Mary I and Queen Elizabeth I – were born at Greenwich, too. In January of 1536 Anne Boleyn delivered a stillborn son at Greenwich early in her labour. It is said that her travails were brought on after discovering her Henry unable to wait for her lady-in-waiting Jane Seymour.

Henry’s sickly son and heir Edward VI died at the palace in July 1553, aged just 15.

The Tudor king’s royal footprint spreads wider than modern-day Greenwich: a little further along the water at Deptford, he founded the Royal Naval Dockyard.

Elizabeth I held a lavish party here to mark her long-awaited accession to the throne in 1558. Then in 1619 King James I had the park encircled with a brick wall. Later still, King Charles II had the park re-landscaped by the French landscape gardener André Le Nôtre (who also beautified St James’s Park).

All that and we haven’t even got to the bit about the royal Greenwich that stands here today.

TEN KING HENRY VIII’s ON FILM AND TV

Given that Hollywood stars are encouraged to keep themselves in good shape, there has been a dearth of, ahem, larger actors available to play the King – which has resulted in something of a festival of fat-suits and Tinseltown makeovers. Here are just ten…

Carry On Henry (1971)

The Carry On films are as British an institution as the Royal Family itself. This great British comedy franchise was never going to be reverent, given the subject matter and the Carry On reputation for seaside postcard humour. Sid James pads up as Henry but makes no attempt to hide his filthy, cackling laugh, thank goodness. Ludicrously hilarious.

The Tudors (TV 2007–2010)

‘Jonathan Rhys Meyers is King Henry 8’ – thus ran the advertising copy for the final season of this Canadian-made TV series. Beneath this line, the picture showed a lightly bearded JRM standing arms outstretched, not an ounce of him hanging the wrong way, while the Pussycat Dolls posed in the background behind him… Oh, hang on, those are the six wives in the background, not pop stars. Hmmmm. The New York Times TV reviewer summed the whole thing up perfectly, describing it as a ‘steamy period drama... which critics could take or leave but many viewers are eating up.’ Ludicrously hilarious in a different way from Carry On Henry.

The Other Boleyn Girl (2008)

Features the ‘other’ King Henry again – slimline and smouldering in the shape of Eric Bana.

The Other Boleyn Girl (TV 2003)

The other Other Boleyn Girl sees Jared Harris – son of Richard Harris – step up to the part in a performance far more in the Keith Michell mould (see below) than the bodice-ripping stuff of recent years.

Henry VIII (TV 2003)

As with Sherlock Holmes, each new generation of TV programme-makers wants to have a tilt at re-telling Henry’s tale. Ray Winstone brings heft to the role, both physical presence and charisma.

The Six Wives of Henry VIII (TV 1970)

Australian-born Keith Michell fronts a welter of British theatrical talent and brings the King alive for an entire generation of TV viewers in the UK.

The Prince & The Pauper (1977)

Big-screen adaptation of the old tale of a poor boy swapping places with a prince sees Charlton Heston keep his shirt on as King Henry VIII.

Elizabeth R (TV 1971)

Keith Michell reprises his role, this time in a cameo as Elizabeth’s father.

A Man for All Seasons (1966)

We remember the great Robert Shaw for his villains (notably in From Russia With Love and The Sting) and for his wild Irish seafarer in Jaws. And he brings an undercurrent of wild villainy to his Henry in Robert Bolt’s tale of Sir Thomas More, who refused to recognise Henry as Supreme Head of the Church of England.

The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933)

It would take nearly 40 years and the great performance of Keith Michell to unseat Charles Laughton from the throne of King of the Screen Henrys. The movie was the first ever non-American film to be nominated for an Oscar.

Changeable types, these royals. Charles II decided that he wanted to replace Placentia with a fashionable new palace in the classical baroque style. So the Gothic terracotta palace was pulled down and replaced by the beginnings of a design by Christopher Wren. But all sorts of financial uncertainty and delays dogged the new palace and the scheme fell into debt. By the time of Charles’s death, only the west wing was complete.

James II came next and left the Greenwich project well alone, concerned as he was with the business of the old faith being returned. But with the arrival of William and Mary and the so-called Glorious Revolution of 1688, a revolution of a different kind was wrought on Greenwich.

Out went palaces and in came the Royal Hospital for Seamen (2), as a thank you to all the valiant sailors who had brought Britain to victory at the Battle of the Hague in 1692. Where the land meets the water, the water equivalent of the Royal Hospital at Chelsea (for old soldiers) was born.

The structure that housed this lavish retirement home for those who had served in the British Navy still stands today.

Enter that man Wren again. Sir Chris wanted it to have one big dome as the dominating feature, but Mary still wanted the Queen’s House (more of that later) to be seen from the river. So Wren split his big dome into two smaller ones, creating a courtyard in between so that the Queen’s House wasn’t bullied out of the picture.

The design eventually evolved into four graceful quadrants and the site as it stands today is widely considered to be the finest classical landscape on these islands. Each colonnaded façade mirrors its opposite number in a glory of all things classical baroque. This was Wren’s favoured style and, as the term suggests, is a happy marrying of two architectural schools – the classical, typified by graceful columns supporting triangular stone pediments mimicking the temples of ancient Greece; and the exuberant carving of baroque-age swags of fruit and flowers, cherubs and every nautical emblem imaginable, from mermen to the prows of sailing vessels.

Queen Mary died of smallpox in the epidemic of 1694, but a devastated William saw that her wish was carried out and building on the Royal Hospital commenced in 1696.

The naval pensioners arrived in 1705, blue-coated, battle-scarred and keen to get stuck into their beer and ’baccy rations – the great rewards for a life of service. The structure, however, designed as a fitting tribute to the scale of sacrifice made by these embryonic empire-building tars, was simply too grand for its practical use, and was more monument than domicile. The Painted Hall as dining room was particularly ill suited to its purpose.

How’s this for a restaurant review, from one Captain Baillie, who, in 1771, complained thus: ‘Columns, colonnades and friezes ill accord with bully beef and sour beer mixed with water.’

The pensioners were forced to struggle on in draughty luxury until 1869 when the building became the Royal Naval College. Today it houses the University of Greenwich and the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance.

THE ROYAL FAMILY, THE NAVY AND SEAFARING

King William IV

Nicknamed ‘Sailor Bill’ thanks to having spent much of his life associated with the navy. Took the throne upon the death of his brother King George IV. Was, at the age of 63, the oldest man to become king of this country… so far.

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh

Rose to the rank of Commander while serving with the Royal Navy and was mentioned in dispatches in 1941. At the time of writing he is an Admiral of the Fleet.

King George VI

Last royal to see action in the navy – fought in the battle of Jutland in 1916 while still Duke of York.

Prince Andrew, Duke of York

Currently Commodore-in-Chief of the Fleet Air Arm. Saw active service in the Falklands Conflict of 1982. The slight distinction from his grandfather (see above) is that he didn’t engage in combat.

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

Commanded his own ship in 1976 and is, at the time of writing, an Admiral.

King James II

Appointed Lord High Admiral (as Duke of York) after the Restoration.

Queen Elizabeth I

Knighted Sir Francis Drake at nearby Deptford in 1581.

Queen Elizabeth II

Knighted Sir Francis Chichester for his achievement in circumnavigating the globe single-handed. The ceremony took place at Greenwich with the self-same sword used by her namesake some 386 years earlier.

One of the most spectacular dining halls in the world, painted to celebrate British naval supremacy over Europe… the artist also took great care to puff up our only joint ruling monarchs King William III and Queen Mary II. Such is the hagiographic spectacle that just one glance upward at the ceiling will make you say: ‘Hang on… I thought we got rid of all that Divine Right of Kings business.’

It is the work of Sir James Thornhill – who was also responsible for the inside of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral (see Chapter 9). It took him 19 years of his life to complete and for his trouble he was paid the not particularly kingly sum of £3 per square yard for the ceiling and £1 per square yard for the walls.

Centre stage in the main ceiling are Peace and Liberty triumphing over tyranny. William and Mary are seated on fluffy clouds in heaven. Apollo shines down on them, as Peace (with her doves and lambs) hands an olive branch to William, who in turn gives the red cap of Liberty to Europe.

Beneath, cast out of heaven, is the defeated enemy Louis XIV, his sword broken (it doesn’t take a Freudian genius to read the emasculation metaphor) and wearing yellow, the colour of cowardice and treachery.

No inch of wall was left plain. Whether this was driven by artistic choice or the pound-a-yard business, I’m not sure. Thornhill crammed it with nautical imagery: cannons, anchors, ropes, mermen and mermaids. It’s the fine art version of Britannia asking of the waves, ‘Who de man?’ and the waves replying ‘Britannia, you de man, you de man.’

How’s this for a wedding present: King James I granted his new wife Anne of Denmark the manor and palace at Greenwich in 1613.

Sure beats matching bathrobes.

Anne then employed the one and only Inigo Jones (who had arranged many masques and balls for the Queen) to design her a house truly fit for a queen. The Queen’s House still stands today. And it bears all the fingerprints of Jones’s experiences on his grand tour of Europe.

Queen Anne was a great patron of the arts and had a passion for architecture and garden design – this last being evident when we gaze upon the Queen’s House.

When we throw the word ‘revolutionary’ about the place, it conjures up images of violent change and upheaval. When we throw it at such an architectural masterpiece as the Queen’s House in Greenwich, the modern sensibility shrugs its shoulders and says ‘Revolutionary? Huh?’

To the modern eye the symmetry of the building, the pale stone, the columns, the sheer grandeur of the place speak of the established order, the status quo. Yet in the early 17th Century, such a style was new to these islands. The Queen’s House is the first neoclassical building in the country, inspired by the work of the Italian architect Andrea Palladio, after whom we name the Palladian school of architecture.

If that still doesn’t seem revolutionary to you, then think of the power of its impact. The style has so captured the British imagination that it remains, for many, the benchmark of architectural taste. Four hundred years down the road, many Britishers still have difficulty seeing beyond the Palladian, the neoclassical. One can see this impact right through our society. Listen to our dear Prince of Wales hold forth on building design, or look at the custom-built modern-with-pseudo-classical-touches pile of any highly paid footballer!

We can only wonder what Queen Anne herself would have thought of such retro tastes, being, as she was, such a dedicated follower of fashion. So much so that it is said she had one of her portraits amended to show her sporting a more up-to-date hairstyle.

Two wonderful and exhilarating views of the Queen’s House can be taken in at Greenwich – and I recommend both, each for different reasons.

With the River Thames to your back, the Queen’s House is the very picture of symmetry: two rows of seven windows, with a grand curved staircase slap bang in the middle. It is linked to two additional wings by grand colonnades which give the development an air of supreme confidence in its own beauty. It is as if the old place is stretching out its arms and basking in our admiration. The sweeping foreground that leads up to the building is preserved as part of the Grade I listed status of the location.

The second view is more challenging – not least because one has to climb a hill to enjoy it. Looking out from near the Royal Observatory, the backdrop is one of utter modernity with the glass and concrete megaliths of Canary Wharf rising up behind. The Queen’s House, however, is far from dwarfed or intimidated by this crowd scene. In fact it looks even grander from this angle, thanks to six columns that grace its upper floor. The view will stir the heart, or boil the blood, depending on one’s opinion of modernity in architecture. As with the Albert Memorial (see Chapter 1), no one will simply shrug their shoulders upon taking in this view.

The house was begun on the say-so of Anne, but completed in 1637 by Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I. Henrietta had the famous ‘tulip stairs’ installed – the first centrally unsupported staircase in Britain. It is now part of the National Maritime Museum and plays its part in London’s 2012 Olympics as a VIP centre.

As we will see in Trafalgar Square (see Chapter 10), poor old King William IV never did get his equestrian statue.

Perhaps the statue that he did get in Greenwich is more appropriate anyway. There he stands in full naval regalia. He’s been here since 1936, having first taken up residence in King William Street in the City of London from 1844. Once a wandering sailor, always a wandering sailor.

From King William IV, the throne goes to Queen Victoria, his niece. Sailor Bill died without legitimate issue. He had ten illegitimate children – all by the same woman. Whether this adds a veneer of respectability to the whole affair, I’ll leave you to judge. I’m sure you haven’t bought this book as a moral treatise.

The woman in question was Dorothea Jordan, an actress – quelle surprise – who enjoyed a 20-year relationship with the King while he was Duke of Clarence. Their children took the name FitzClarence, but the relationship ended when William became king.

As king, William shunned the extravagance of his brother George IV and was known to walk in the streets of London in the early part of his reign. We can count among his descendants through his illegitimate children Mr David Cameron, the Prime Minister who has headed the coalition government from 2010. What would Cromwell say?

A NICE SIT DOWN AND A CUP OF TEA

To the London visitor, Greenwich may seem a little off the beaten track. But as we have seen, a boat trip makes short work of the eastward journey, and when you get there you can graze on the history of, well, the history of everything: land, water and time itself.

Not too shabby a place to eat and drink, either.

On the main drag

National Maritime Museum

Park Row, SE10 9NF. DLR: Cutty Sark; Rail: Maze Hill

The 16” West brasserie lies precisely 16 seconds to the west of the meridian. Who’s going to argue about time down Greenwich way? The chefs cook with locally sourced produce where possible and booking is advisable.

The more plainly named Museum Café may sound like the brasserie’s frumpy sister, but this is far from the case. The views from the sun terrace are among the best Greenwich has to offer.

Something a little stronger, perhaps?

The Trafalgar Tavern

Park Row, Greenwich SE10 9NW. DLR: Cutty Sark; Rail: Maze Hill

Built in 1837 – the year Queen Victoria took the throne – this riverside pub is one of London’s treasures. You’ll need to book if you want to eat, but a pint and a sit down for a little read usually isn’t too much to ask – although weekends are naturally very busy.

Sssshhh. It’s a secret

Goddard’s Pies

Fountain Court, off Greenwich Church Street, SE10 9BL. DLR: Cutty Sark

Pie and mash is traditionally the food of the working-class Londoner – and it’s almost a London bygone, too, with fewer traditional pie shops remaining open in London with every passing year. Goddard’s is still going strong and has been since 1890. A meat pie, with a dollop of mashed potato drenched in a parsley gravy known as ‘liquor’, is hale and hearty fare. But where to sit when you’ve bought your food? Is one of London’s most beautiful parks, surrounded by 400 years of history, good enough for you?