London’s legendary East End polarises the capital’s opinion almost as much as the institution of monarchy itself. It is as celebrated in some quarters as it is maligned in others. And legendary is the word. The East has long been the starting point for the peoples of the world as they embark upon their journeys in this, our great capital city. Their experiences of arrival, assimilation, of hardship and victory against the odds are the very stuff of great storytelling.

That their tales have been told and retold aloud makes East London the capital’s home of the oral tradition of storytelling. That the tales often have their genesis in the native tongues of the immigrants is important, too. Yiddish elbows its way into English; thieves’ argot barges its way in; profane costermonger ‘backslang’ (a good example of this is ‘boy’ becoming ‘yob’) sticks like mud to the everyday talk of Whitechapel. And as the tectonic plates of language shift and collide and merge, a new language is born, the lexicon of the East End.

If the East End is another country with a language all its own, then it will immediately defy governance by the Divine Right of Kings. So surely this means that beyond Aldgate lies a royal wasteland?

Far from it. Dealing as we are with the World’s Greatest Soap Opera (with apologies to the Kennedy clan, but I’m afraid you really are Knots Landing to our Dynasty), the oral tradition can only help heighten the stories, bringing colour (sometimes lurid) and drama (sometimes far-fetched) to the table, along with one other crucial ingredient: sedition.

In the disobedient and unruly East End we can find the roots of British dissent and scepticism alive and well. Not everyone in this country would send them victorious, happy and glorious. As with all truly great tales, there are two sides to the story. And that is nowhere more evident than here in the East End: even where the wildflowers of dissent abound, the patriotic roses still thrive.

And so it follows that it is here in the East End that you will find the Royal Family both more slandered and more exalted than anywhere else in the metropolis. So let’s begin with the slander…

It is almost as if that most unfathomoble of all London tales could not survive in the East End if it didn’t have a royal element. That character so beloved of the movies – the gentleman killer in white tie and tails and silk hat – is all the more vivid if we have his carriage rattling along The Mall as both the sun and Buckingham Palace recede behind him.

But before we set too dramatic a scene (gas lamps popping into limp life, wan faces lurching at the carriage window for alms, only to be beaten away by the driver’s crop and all that business), let’s pause to reveal the truth of the tale…

The Duke of Clarence was not Jack the Ripper.

(This ‘reveal the end at the beginning’ technique never did Columbo any harm so we’re sticking to it.)

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale – Eddy to his family – was the oldest son of the Prince of Wales (the man who would become King Edward VII) and Princess Alexandra. He is first mentioned in connection with London’s most lurid and addictive tale in 1962 – some 74 years after the murders were committed (the case seems to have developed a life of its own with each generation throwing up a new ‘suspect’).

Broadly, the conspiracy theory runs thus: the Duke of Clarence was a helluva fella for the prostitutes. Some versions have him fathering a child by a prostitute in the East End; others say he married a fallen woman. Queen Victoria, as one might expect, was not amused. The shadowy forces of ‘the authorities’ kidnap the subject of the Duke’s affections and have her lobotomised, thus rendering her mute. The witnesses at the wedding are then hunted down one by one and killed to preserve the good name of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

Donald Rumbelow – the great ‘Ripperologist’ whose prose is refreshingly free of the clammy enthusiasm that so often sticks to the pages of Ripper books – in his definitive The Complete Jack the Ripper characterises the Duke as a reluctant soldier, a dandy with a weak constitution, not necessarily the captain of the pub quiz team. This last point alone, that he was not the sharpest tool in the box, gives rise to the counter-theory that he would therefore lack the cunning to wield the sharpest tools in the box.

History has him dead just four years later in the flu pandemic of 1892. Our theory from 1962 has him dead of syphilis – a convenient hook upon which to hang a Ripper conspiracy. Most sources accept that he was shooting in Scotland for at least two of the murders. But our conspiracy theorists rush in here again, saying that he may have been in a psychiatric institution near Sandringham, having been caught in a raid on a gay brothel in Cleveland Street. With Queen Victoria expressing concerns regarding the Duke’s ‘dissipation’ in private letters available to fan the flames, the story shows no sign of going away any time soon.

Artillery Lane dates from the 1680s, and its name is a fingerprint from the reign of King Henry VIII. The land was used during Henry’s reign for military manouevres and training. The Honourable Artillery Company, which claims to be the oldest regiment in the British Army, gained its royal charter in 1537. The location is commemorated with a board detailing Henry’s artillery’s history on the wall in Sandy’s Row, a short, narrow, early Georgian cut-through, the darkness of which is exacerbated by the modern glass buildings that crowd in around as if to conceal its presence out of shame for such an aged street.

The history of the East End is very much an alternative history of London, the area growing with its proximity to the docks and being shaped by the pollution of the Industrial Revolution borne on the southwesterly wind.

Two London heritage staples stand out by their general absence: blue plaques and statues to the great and the good.

Yet the Royal London Hospital has both.

The London Infirmary from 1740, then the London Hospital from 1748 until 1990, when it became the Royal London, the hospital has strong ties to the Royal Family in the Edwardian era.

Viewing it from the northern side of Whitechapel Road, the side with all the market stalls, the hospital is an imposing edifice indeed. To the western end the landing pad for London’s only air ambulance breaks the grim 19th-century lines. Behind the building stands the new wing – a paragon of modernity in blue glass. The overall effect is of a carer in a blue high-visibility vest chaperoning the aged, yet dignified, old lady across the Whitechapel Road.

The other flash of blue is the plaque to the left of the front entrance, dedicated to Edith Cavell, the English war hero of the 1914 to 1918 conflict, who was executed by German firing squad for aiding the escape of British prisoners.

On this building, a plaque could just as easily have been erected to the great children’s charity campaigner Dr Thomas Barnardo who worked here (also a Jack the Ripper ‘suspect’, believe it or not); or to Sir Frederick Treves, the famous surgeon whose base was at the London Hospital.

Treves performed the appendectomy on King Edward VII in 1902 that saved the King’s life and allowed him to take the throne on his coronation day in August that year.

The King had stubbornly insisted that, despite the need for an operation, the coronation would go ahead as planned on 26 June 1902. Upon consultation with Treves and the great Joseph Lister, however, the King was informed that the peritonitis (a disease of the abdomen) from which he was suffering would surely take his life without surgical intervention. The coronation was put back, the King’s life was saved and almost everyone lived happily ever after. Among those left not so happy were the overseas delegates who had already arrived for the 26 June affair (no small matter of nipping over on easyJet in 1902) and the manufacturers of commemorative china who now had a mountain of dud tea sets on their hands. Edward’s coronation went ahead on 9 August 1902.

Treves (born in Dorchester in 1853 and founder of the British Red Cross Society) is also connected to one of the East End’s most famous 19th-century tales – that of the Elephant Man.

Joseph Merrick, a native of Leicester and suffering from the condition neurofibromatosis, had washed up on the shores of Whitechapel in 1887 with a travelling freak show that had taken up residence on Whitechapel Road opposite the hospital in a then recently vacated greengrocer’s business (at the time of writing it is home to the International Saree Centre). Billed as the Elephant Man – his condition caused extreme growth of excess flesh about the skull and legs, with a stooping curvature of the spine – he was discovered by a curious Treves. Following a circuitous route that took Merrick away to the continent, Treves took him in at the London Hospital.

(Note: Once again, believe it if you will, Merrick is also a ‘suspect’ in the Jack the Ripper case thanks to his cameo appearance in the 2001 Ripper movie From Hell. In fact, to draw a line under the whole Ripper business, it’s fairly safe to say that, from this point in the book, whenever you read a famous name, then someone somewhere probably has a theory ‘proving’ that they were Jack the Ripper.)

Merrick became the subject of a successful Broadway play and David Lynch film (in which Sir Anthony Hopkins played Treves). In his brief lifetime he became something of a cause célèbre, and was even visited by the then Princess of Wales, Alexandra of Denmark.

Princess Alexandra features in the 1980 film version of The Elephant Man, played by the English actress Helen Ryan. Ms Ryan had played Alexandra five years earlier in the ITV series Edward VII and went on to play Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands in the 2002 US TV movie Bertie and Elizabeth. Princess Alexandra presented Merrick with a signed photograph which became one of his most prized possessions and it is said that she sent him a card each year at Christmas.

Behind the Royal London Hospital itself, where Merrick resided, that second kind of elusive commemoration can be found: a statue dedicated to Queen Alexandra.

In bronze, the work of George Edward Wade, Alexandra is captured in her coronation robes with the sceptre in her hand. Even taking into consideration that art and artists have long been very kind to our Royal Family, Wade leaves us with the impression of a strikingly handsome woman by anyone’s standards. One detail in particular captures the imagination: the hem of her coronation gown is draped casually over the edge of the plinth. It is as if Her Majesty has just clambered back up upon it, perhaps hurriedly so that no one would have noticed her doing so, after performing some good deed here in the East End.

And, indeed, as Princess of Wales, and accompanying her husband, she opened two new buildings at the London Hospital in 1887. But it is for introducing the Finsen light cure for lupus – a disease of the immune system – to England, a fact commemorated on the plinth beneath her, that her statue stands here.

Standing at the junction where Whitechapel Road becomes Mile End Road, with Cambridge Heath Road wending in from the north and Sidney Street raging in from both the south and the bloodied pages of East End folklore (it was the scene of a gun battle and siege in 1911), one can enjoy (or endure) a festival (or riot) of architectural styles.

Making a 360-degree turn, the eye is assailed by anonymous 1980s ‘improvements’, functional 1950s housing, award-winning 21st-century radicalism and fine examples of 19th-century pubs. It is the perfect spot to indulge in two of the great favourite pastimes of the British: complaining about even the smallest development in architecture since 1840, and banging on about the Second World War.

The war remains a vivid and living London talking point simply because of junctions such as this one – the sheer volume of post-war buildings on view suggests that something must have happened to bring about such wholesale change. The East End, with its proximity to both the business of money in the City and the London Docks, became a prime target at the height of the Blitz.

Enter the woman who would become a legendary, much-eulogised royal figure as the Queen Mother: Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, our wartime monarch.

Legend has it that Queen Elizabeth was once described by Adolf Hitler as ‘the most dangerous woman in Europe’, given her effects on the morale of Londoners at the height of the savage Luftwaffe attacks by night. Yet the myth of her relationship with the people of the East End did not have an easy birth. To tell the full story we must first undertake the delicate business of dismantling a beloved legend. But by the time we have rearranged the fragments and rebuilt it piece by piece, it will shine even more brilliantly than it ever did before.

HM Queen Elizabeth’s first visits to the East End in the early days of the bombing provoked open hostility from those whose lives had been devastated. Dressed in her finery – a decision attributed by some to Elizabeth’s view that it would boost morale, to others that it was merely a courtesy to wear one’s best clothes when visiting – some accounts have her being heckled and even pelted with rubbish thrown by grief-stricken and rage-addled bomb victims. When Buckingham Palace was bombed – the Royal Family remained ‘in residence’ but secretly spent their nights 20 miles away at Windsor – Elizabeth uttered one of her most famous lines: ‘I’m glad we’ve been bombed. It makes me feel I can look the East End in the face.’

From this point her East End visits received a heroine’s welcome, and the seeds of her populist legend were sown.

Her eternal place in the hearts of Londoners is locked there by the golden key of the following quote, upon being advised to evacuate to Canada with the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret:

‘The children won’t go without me. I won’t leave the King. And the King will never leave.’

Here at Mile End, some 600 years earlier, royal words formed part of a very different kingly legend. It was at Mile End, on 14 June 1381, that the 14-year-old King Richard II agreed to rebel demands made following the introduction of the Poll Tax, which sparked what we now know as the Peasants’ Revolt. The following day he met Wat Tyler, one of the rebel leaders, at Smithfield and confirmed his promise of one day earlier. Wat Tyler was later killed at the scene by the Mayor of London, William Walworth.

And the King soon withdrew his promises of pardon and freedom. Politics was ever thus.

TEN ROYAL PUB NAMES

White Hart: The White Hart pub that stands where Whitechapel Road meets Mile End Road is named after the emblem of King Richard II and remains a popular pub name all over these islands.

King’s Head: A tribute to King Charles II, who is held in high esteem by the nation’s dipsomaniacs for having the pubs reopened after Cromwell had called time. The Old King’s Head on Borough High Street (Tube: London Bridge) is a fine example.

Royal Oak: Named after the oak tree in which Charles II concealed himself from the Roundheads during the English Civil War. (Royal Oak, Columbia Road. Rail: Hoxton)

The Feathers: The emblem of the Prince of Wales – see also the Three Feathers and, more plainly, the Prince of Wales. (Try The Feathers, just around the corner from St James’s Park station.)

The George: When not in tribute to one of our six King Georges, then it refers to St George – the cult of whom was brought to these islands by King Richard I. (London’s most famous George Inn can be found in Southwark, just off Borough High Street – see the end section in Chapter 2).

The Duke of York: A royal title since the 1300s, the Duke of York has become king twice in the past century – George V and George VI. (Try the one at Roger Street, WC1. Tube: Holborn)

The Blind Beggar: The blind beggar in question was a heavily disguised Henry de Montfort, who posed as said sightless vagrant to escape Prince Edward (later Edward I) in the aftermath of the second Barons’ War in 1263. King John had been Henry’s grandfather. The Blind Beggar pub (Tube: Whitechapel) is integral to the story of the Krays (see our sister volume Bloody London).

Queen of Bohemia: Eldest daughter of King James I of England and VI of Scotland.

White Lion: Emblem of King Edward IV.

Three Kings: Usually in recognition of the three wise men, and not the monarchy, with one comic exception: the Three Kings of Clerkenwell (Tube: Farringdon) has a pub sign featuring three kings, one of which is King Henry VIII, the other two being King Kong and Elvis Presley.

A NICE SIT DOWN AND A CUP OF TEA

In the North, South, East and West chapters, where we cover a wider area of London, the places suggested to stop and have a cup of something reviving and a browse at this book may not necessarily be placed perfectly to strike out to see all the locations in one trip. They will be situated near (or at) at least one of our Royal London sites – and all will provide a warm welcome.

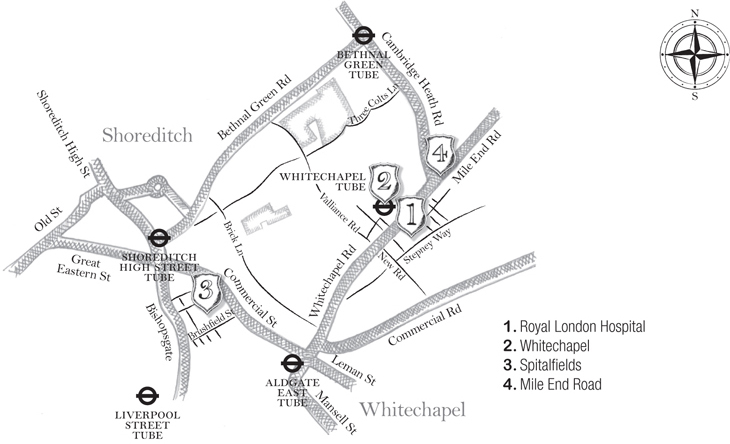

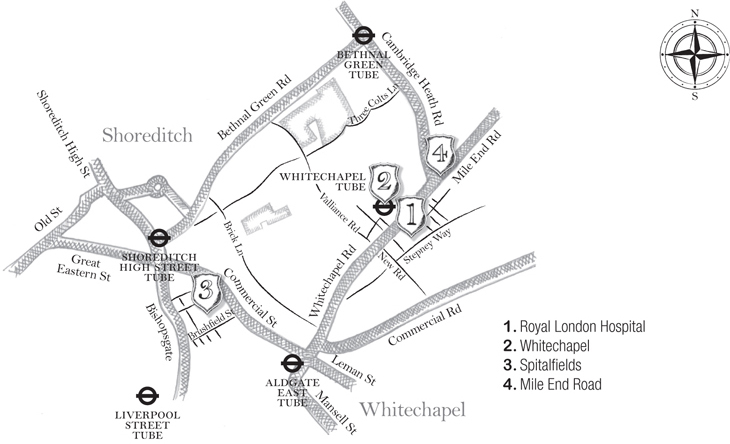

For the purpose at hand, one can approach the East End from two stations – from Liverpool Street (commencing at Spitalfields) or Whitechapel. Decide where you want to rest and relax and choose your station accordingly – there are comfy corners aplenty near both stations.

On the main drag

Andaz Liverpool Street

40 Liverpool Street, EC2M 7QN. Tube: Liverpool Street

Given that our subject matter exists somewhere way beyond posh, we’re going to struggle to provide a location in which to imbibe and read that matches the habits of our Royal Family.

But if we can’t do truly posh, we can at least go for swish.

Andaz – formerly the Great Eastern Hotel – was designed by the great Charles Barry Jr. Its options range from lounge to cocktail bar. There’s even a traditional(ish) pub on the premises, the George. Although be warned: the pub does show football matches on big, plasma screens and can get a bit noisy, especially of an evening. Unfortunately, we can’t provide a recommendation for a pub that shows live polo matches (much more in keeping with our subject). Do drop me a line if you know of one.

Something a little stronger, perhaps?

Dirty Dicks

202 Bishopsgate, EC2M 4NR. Tube: Liverpool Street

Famed as being named after the real-life character who inspired Dickens to pen Miss Havisham – Nathaniel (Dick) Bentley’s fiancée died before the wedding and he lived a dusty, lonely existence the rest of his days.

The Blind Beggar

337 Whitechapel Road, E1 1BU. Tube: Whitechapel

Fabled East End watering hole associated with 1960s gangsters the Krays. A much more peaceful place these days – and it does have royal associations in its name, as we have seen earlier in this chapter.

Sssshhh. It’s a secret

The Market Coffee House, English Restaurant

50/52 Brushfield Street, E1 6AG. Tube: Liverpool Street

There’s precious little that’s secret about this part of town these days, with the glare of the fashionable spotlight constantly trained eastward. Every conceivable multinational coffee corporation has elbowed its way into the East End this past decade. But it’s still possible to sit in a non-homogeneous environment and enjoy great service from a family-run business. They’ve been here in their current form only since 2001, but parts of the building date back to the 1600s. The interior is composed of the salvaged remains of an old pub. Despite its relative modernity, it achieves a genuinely traditional feel.

Have the cooked breakfast. To hang with your doctor.