There once lived a family—a mama, a daddy, a little girl, and a little boy. Every day, the father and son would leave the house to go work in the fields. The mother and daughter stayed home. They cleaned the house, cooked the food, sewed the clothing, tended the garden, and did other nearby chores.

One day, the mother said to her daughter, “Go to the orchard and pick pears. Now, don’t you go giving even one away. If you do, I promise, I’ll kill you.”

The little girl left the house. She walked over the hill, through the woodlot, past the barn, and on down to the orchard. When she got there, she did not see any pears. She looked carefully at each pear tree, and finally she found one fallen pear. It was overly ripe, right on the verge of turning rotten, but it was the only one she could find, so the girl carefully wrapped it up in her apron and headed home with it.

Now the moment the little girl left for the orchard, the mama disguised herself as an old woman. She followed the little girl. And when the girl came up the hill from the orchard, there the mama was, sitting on a tree stump looking for all the world like a poor old woman.

The girl saw the old woman, and she stopped, “Good afternoon, Granny, how are you doing today?” Now, the girl did not think the woman was her grandmother; she called all older women Granny, just to be polite.

“Oh,” said her mama, changing her voice to sound like an old woman, “I’m not doing too well. I’m so hungry. Would you happen to have anything I could eat?”

The little girl thought about the pear, but she remembered what her mama had said, so she lied, “I’m sorry, Granny, but I don’t have a thing.”

“Are you sure? Maybe you have just some little something wrapped up in your apron? I’m so hungry, I’m not sure I’m going to be able to reach my home. I had to stop here just to rest.”

The girl thought about the pear, and she thought about what her mama had said. She didn’t know what to do. Finally, she decided the right thing was to give away the pear. “After all,” she thought, “it’s almost rotten anyway, so Mama probably would not be very pleased with it anyhow. And no person should have to go hungry. It will be best if I just tell Mama there weren’t any pears, and there really weren’t any on the trees—I found this one on the ground.”

So, she handed the pear to the old woman. The old woman thanked her, and the girl walked on toward home.

The moment the girl disappeared around the edge of the barn, the mama threw off her old woman disguise and hurried home, taking a shortcut to get ahead of her daughter.

When the daughter reached home, her mother asked, “Where are the pears?”

“Oh, Mama,” the girl said, “I looked at every pear tree and couldn’t find a single pear in any of them.”

“Are you sure you didn’t find any pears?”

“Not a one,” said the girl.

“Not even on the ground?” asked her mother.

The girl hesitated. She did not want to lie to her mother, but she was afraid to tell her the truth.

“You gave away the pears, didn’t you? After I told you not to, you up and gave away our pears.”

The girl couldn’t help herself. She told the truth. “Oh, Mama, I really didn’t find any pears on the trees, but I found one pear on the ground. It was nearly rotten. Then on my way home, I met an old woman. She was so hungry, I gave her the pear. It was nearly rotten anyway, Mama, so I didn’t think you’d want it. And the woman was so hungry.”

The mama stared at her daughter and shook her head. Then she said, “Go out to the porch and bring in the chopping block.”

“Why, Mama?”

“Because I told you to, and I’m your mama.”

The girl went out and she brought the chopping block inside. “Now then,” said her mama, “go get the axe.”

“Why, Mama?”

“Because I said so, and I’m your mama, that’s why. Now, go get the axe.”

So, the girl brought the axe inside. Then the mama said, “Go upstairs to your bed and get your pillow.”

The girl did as asked. When she returned with her pillow, her mother said, “Now, set the pillow on the chopping block and lay your head down.”

“No, Mama, you’re going to chop my head off.”

“I wouldn’t hurt you. I’m your mama. Now lay your head down.”

“No, Mama, no! You’ll kill me!”

“Don’t be silly. I’m not going to kill you. I’m your mama. I wouldn’t hurt you. I love you. You’re my little girl.”

So, the girl laid her head on the pillow, and her mother took up the axe and chopped her head off. Then the mother buried her daughter’s head and body in the garden.

That evening, when the father and son came home from their work in the fields, the father noticed his daughter’s absence, “Where’s my little girl?”

“Oh, one of her cousins came by and invited her to visit, so she’s gone over there.”

“Well, will she be back in time for supper?”

“Oh no, it was one of your relatives that lives far away. She’s gone off to visit for a long time. It’ll probably be six weeks before she’s back.”

“Six weeks? Why didn’t she come to the fields to tell us good-bye?”

“Oh, you know how she is when her cousins come around. She was so excited about going to visit with them, she didn’t even think about taking time to say good-bye.”

The father didn’t think that sounded like something his little girl would do, but her mother spent more time with her than he did, so he figured she must know what she was talking about. Later that night, the father, mother, and brother ate their supper and went on to bed.

The next morning, the mother said to her son, “Run out to the garden and dig up a few potatoes. I’ll fix us some fried potatoes for our breakfast.”

The little boy went to the garden. He walked over to the row of potatoes, squatted down, and thrust his hands into the hill to feel for some potatoes. And then he heard singing:

Brother, Brother,

don’t pull my curly hair.

Mommy killed me

over one little ripen pear.

He jumped up from the potatoes and ran back to the house.

“Daddy,” he said, “I’m having some trouble with the potatoes. I need you to come help me.”

The father and brother went out to the garden. When the daddy reached into the potato hill, he heard:

Daddy, Daddy

don’t pull my curly hair.

Mommy killed me

over one little ripen pear.

The father and brother walked back to the house, where the father said to his wife. “There’s something wrong in the garden. You need to come out here and help dig the potatoes.”

The mother walked out, and the moment she reached the potatoes, she heard:

Mommy, Mommy

don’t pull my curly hair.

You know you killed me

over one little ripen pear.

The mother looked at her husband and son, and she could tell they had heard the song too. Together the father and brother dug in the potato hill, and they found the little girl’s head. The father looked at his wife, “What did you do to her?”

Before the mother could finish her story, he took up the axe and chopped her head off.

The father and brother buried the little girl on one side of the garden and buried the mother on the other. From the little girl’s grave a rose bush grew, but from the mother’s grave all that ever grew were briars.

Leonard Roberts collected ten versions of this tale.2 It was told by both children and adults.

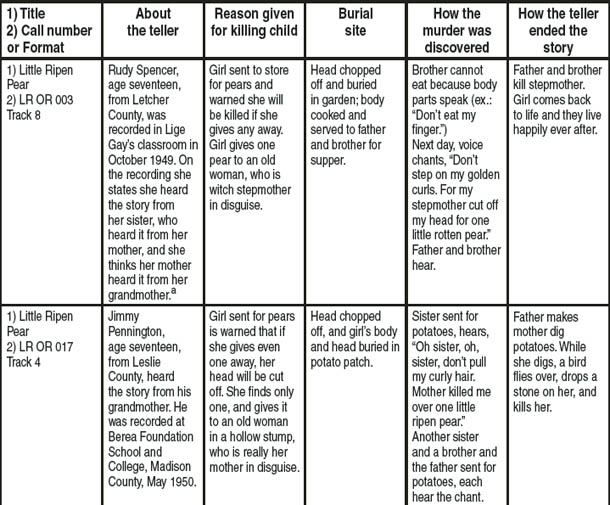

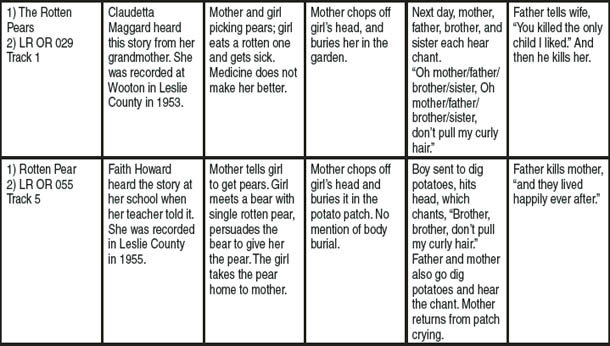

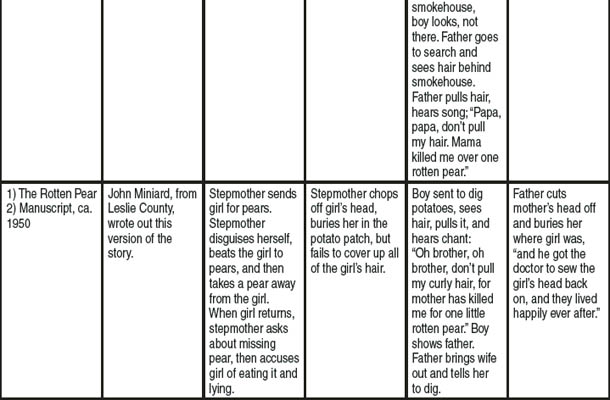

Table 1 shows information from different versions.

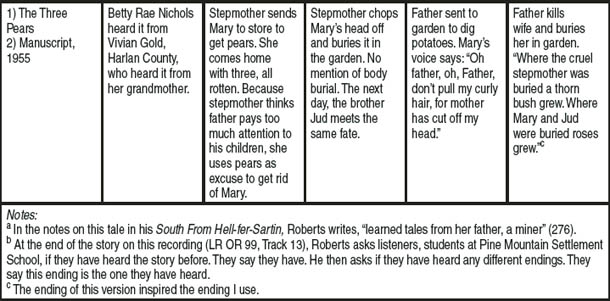

In some of Roberts’s collected versions, the little girl sings; in others she chants. The tune I use in my retelling is not based on any tunes in the collected versions because I worked on a song for my retelling using manuscripts from Roberts’s collection, before listening to the field recordings. Figure 1 shows the tune I use:

It is not elaborate. I intentionally wanted a tune a child could believably sing in a mournful, pleading way, as well as a tune I could readily sing. Yes, I’m capable of what I call “singing pretty.”3 However, when characters sing in a story, it jars my ear if they suddenly burst into song with a sound akin to that of a trained singer when all their dialogue within the story has sounded conversational.

When I tell this story, I also picture, quite specifically, the orchard I remember from my childhood. It was down a hill behind the barn that had been my great-grandparents’ barn. Our house was located on adjoining property, and to reach the orchard from our house I walked up a hill into the woodlot, down a road, past what had been their house (what our family calls “the old house”). From the old house I would have walked up a slight hill to their barn, walked around the barn, and then down a hill to the orchard. I can also picture the shortcut route someone could have taken—from the barn, walking behind the old house toward a different barn, and then through an open field—to beat me back to our house if they really wanted. I can also picture how I would likely not have seen the person traveling quickly by that route because of the old house, and the hills, trees, and other vegetation of the woodlot. So, why does this matter? And if it is so important, why don’t I explain it in my telling of the story?

Table 1. “Little Ripen Pear” Comparison Chart

It matters because until I can truly picture a story, I cannot tell it. Making the setting concrete by picturing the land where I grew up is one method for helping myself see the story. I know if I can see the story, and take time to see it as I’m telling it, my listeners will be able to see it too. Will they see the exact same picture I see? Absolutely not. Instead they will create their own images of the tale, using their imaginations to picture the setting, costume the characters, and bring the story to life in their minds. As storytellers are fond of saying: Put ten listeners and one storyteller in a room, and when the teller tells a story, eleven different stories will be heard.4

Yes, I suppose it could be possible to tell stories with such minutely detailed descriptive language that the listeners’ images would be identical, or nearly identical. However, doing that would rob storytelling of what I see as its greatest strength. I don’t view my life’s work as telling stories. Instead I see my work as strengthening imaginations. After all, the ability to imagine forms the foundation of all planning, hoping, dreaming, goal setting, and inventing we humans do. Because humans love narrative,5 storytelling provides an excellent vehicle for exercising imaginations. When I tell stories, I do not want to control my listeners’ imaginations; instead I strive to leave plenty of room for the listener to imagine the specific details, thus providing a refreshing imagination workout—even through stories as inherently creepy (okay, possibly beyond creepy, even downright disturbing) as “Little Ripen Pear.”