Periplus

I. Embarkation

In the final days of 1959, a Jesuit Scholastic sits at a desk in the seminary library. He is twenty-four years old. Outside, a death knell sounds on the frenetic fifties, while the sixties wait twitching in the wings. In the library, all is peaceful. Or is it merely quiet? Does he care? He must. Regardless of whatever philosophical bent is endemic in the role of seminarian, he is only twenty-four years old—young—and the world, that unwritten void beyond the tall walls of the seminary, still belongs to him. Here, in the print, all is quiet. Silence holds fast. Silence is what precedes the slam of a book, the accidental grind of a chair across well-waxed floorboards. Silence follows everything, is the destiny of everything. The pencil is sharp. His notes already fill an entire legal pad. He writes with the confidence that never fails him in independent endeavors, in moments of solitude:

With perhaps the exception of the mysterious Euthymenes, of whom little is known, the first recorded navigator of the west coast of Africa is Hanno the Carthasinian, whose voyage is reported to us in The Periplus of Hanno.

He makes a note in the margin—this will need citation—and wonders about the Periplus—the “wandering around”—and what he knows from where he sits: mapped worlds blocked horizontally, realms stacked one upon the other, the specter of evolution. Time—a length of rope wound round and round and round it all. Print: words uncoiling as if they too were twisted out of hemp, pausing and then restarting while read: a hushed unspooling as his eyes sweep right and right, the length of the page. Words: carried like oil lamps, illuminating a little in the darkness.

The seminarian silences his breathing.

He uses his own stillness to better understand the rapidly expanding boundaries of time and narrative and domain. No breath, no movement, but he hears his heart—his clock—and remembers the marking of blood through his own tributaries: his personal periplus over which he has no control, that circulating, that wandering around, which will stay with him until his heart no longer marks the second.

There was another young man once—a merchant sailor. Was it really he? He remembers being on a ship—his watch, he was quite alone—peering into the darkness in case something should appear. The world was rolling on beneath him as he bobbed atop it and he felt the rocking of the waves, but not the earth bowling under the ship’s prow, although that was his understanding of what was happening. The blackness was even, and the much-pierced veil of sky, the stars burning hotly through, presented a false stillness. He was the point of reference, the entry, the relevant word, the moment, the now: the circumvolving earth and greater clockwork of the heavens used him as fulcrum and center point.

There was a thought: I am what makes it all happen.

There was another: I am without meaning.

Which was Sturm und Drang? Which rationalism?

This is all very funny, and he laughs. He knows that while the fifties and sixties—with their attendant dances and tunes and sexual mores—play on outside, he is happy in his library. This is reprieve.

On the wall is a painting—a respectfully muddied oil of Saint Ignatius relinquishing his sword, giving it up to God. He is no longer soldier, not yet saint, not yet founder of the Jesuits, not yet inspiration to the seminarian (yet to be born, yet to be inspired); he is merely a disillusioned soldier—receiver of injuries, survivor of prolonged recoveries—who is determined to follow in the path of Saint Francis, although Ignatius (or Íñigo) is not a big lover of animals and likes his shoes, as future Jesuits will like the occasional Mercedes-Benz. In the picture, Saint Ignatius has fallen on one knee; on the other, a sword is miraculously balanced. Something hidden behind a woolly cloud has caught his attention. The saint’s face is a confusion of awe and decision and duty.

Did Ignatius, falling upon his knee, politely wait for God to appear and accept the gift of peace, inaction, and identity shedding: a gift of willful innocence (as if the battle and bloodshed had never happened) and a new man? Was this his destiny? Did destiny contradict free will? Free will, that gorgeous flawed and slippery cliff ’s edge upon which all men travel, defines both him and his relationship to God. There is a response to this that he should know cold, that should save him from having to parse out what is faith—not to be questioned—and what sits in the brain like sand in an oyster: the stuff of meditation and philosophy.

Destiny. Is that something to fear or something to dream on?

Our seminarian stares hopefully at the picture of Ignatius, as though the answer might exist within it.

“This painting will not help you,” says Ignatius. “It is but a metaphor. A lot of good art and,” he looks around at the dun-colored sky, the static rendering about him, “even much average art is composed in such a way as to tell the story rather than present a specific moment in time. It would be unfair to restrict a painter in a way that a writer would never submit to—to submit to the reality. I never fell upon my knee like this. Our brotherhood of Jesuits was not formed with my arms flung wide, my mouth open. We were an intense lot and met in Saint Denis in Paris. It was a meeting of the minds . . .”

All right. All right. No more daydreaming. Take the pencil.

It is your destiny. Take the pencil.

II. Influence

Our seminarian writes “destiny” in the margin, and for one moment it stays upon the page until deemed irrelevant and erased. He writes:

This account, which is extant only in its Greek translation, was originally engraved in Punic on a bronze tablet set up at Carthage, from where Hanno and his party set forth, probably about 500 BC, on a voyage of colonization and, most likely, exploration.

He considers “most likely” and wonders if “unavoidably” would be more appropriate. He writes “hegemony” in the margin, and the word briefly asserts its influence upon the paper before he erases it.

Hanno’s bronze tablet was installed in a temple dedicated to the god Chronos—Old Man Time himself—whom the Carthaginians rather liked. A bronze tablet ensured the words of Hanno a significant march into the future. Where is Hanno’s tablet now? No one really knows. Instead, we have various other people on Hanno. Pliny on Hanno. This book that informs so much of the seminarian’s paper: Ancient Greek Mariners, by Walter Woodburn Hyde. So: Hyde on Pliny on Hanno. And now him: Murray on Hyde on Pliny on Hanno. And somewhere down the road, someone else will jump on board—most likely, perhaps unavoidably, on a journey of colonization and discovery.

III. Scholarship

How has this young man found his way into this library? Man’s job is to find his way back to God, and perhaps a seminary is an obvious place—a place for an unsophisticated mind, let’s not forget his youth—to start the journey. Perhaps it was his grounding in the classics—all those A’s in Latin and Greek. This paper, if he could only make himself write it, will no doubt also be a success—a success unlike Carthage, which flowered in 500 BC, which is why he picks this vague, rosy-fingered chunk of millennium for Hanno’s departure, and then, in 146 BC, following the Third Punic War, was wiped from all but history.

When was Carthage established? Well, Queen Dido, princess of Tyre, founded Carthage, and Aeneas found her sometime after the Trojan War. So if we look at the dates of the Trojan War we can approximate. Eratosthenes says Troy fell in 1184 BC, Herodotus 1250 BC, and Douris 1334 BC Let’s go with Herodotus, he thinks. Everyone else does.

It was Book Four of the Aeneid that got him interested in Carthage in the first place. Aeneas must leave his lover, Queen Dido, because the gods have decided that he is to found Rome. “Leave now, Aeneas. Found Rome!” And in response, no doubt: “Can’t somebody else found Rome? And what’s the big deal if no one founds it? There are plenty of cities already in existence. What’s wrong with Carthage?”

What if the gods had agreed? What would have happened then? Well, Book Four would have been the final book of the Aeneid, and Rome would have never been founded, which would no doubt have affected the history of the papacy, and Ignatius, and therefore our seminarian. What if the gods had said, “Quite right, Aeneas. Back to bed with you! Sorry for the bother.” Was all possibility and direction contained in Book Four?

That was the book he almost knew by heart, but of course, come the final exam, the passage to translate had been something all together different: the passage on Laocoön. Was that from Book One? Well, it had to be one of the early ones because Laocoön’s tale is really that of the Trojan Horse, and his suspicion of it, and the gods yet again favoring Greece over Troy.

Laocoön, high priest of the Trojans, does not trust the Greeks. After ten years of siege, why would he? He says:

. . . equo ne credite, Teucri. Quidquid id est, timeo Danaos et dona ferentes.

Which translates as, “Do not trust the horse, Trojans. I fear the Greeks even bearing gifts.” And we say something similar, although we trust horses and not Greeks. To underscore his justified concern, Laocoön throws a spear at the horse and Minerva (the Greek’s Athena, but this is Virgil), in a rather unsubtle cover-up, sends two serpents up the beach to strangle him; the result is that his “fillets soaked with saliva and black venom,” something our seminarian was understandably nervous about as he penciled his translation on the final, but this was quite correct. A few lines down, Laocoön’s cries of suffering are “like the bellowing when a wounded bull has fled from the altar/and shed the ill-aimed axe from its neck.” “Fillet” and “bull” and “horse” suggesting a metaphorical unity that trumps mere narrative, and indeed our translator was as on his mark as Laocoön himself.

In another account of Laocoön’s strangulation by snakes, this of the Hellenistic poet Euphorion of Chalcis, the presence of the horse was coincidence: Poseidon had been waiting for Laocoön to present himself on the beach since he’d offended the god by having “marital relations” in the temple in front of an important cult statue. The snakes are payback for Laocoön’s wild ways, and Ulysses, who has just dodged the spear tip and now, peering past it through a narrow slit between tempered steel and frayed wood, sees the snakes in hasty slither and the ensuing struggle. He turns to his companions and says, “You won’t believe what just happened!” Since there’s nothing much to do inside the horse, the other Greeks listen, and they do believe, because they’ve been through quite a lot. Although, as we well know, they’re in for even more.

IV. Departure

Our seminarian taps the tip of his pencil upon the paper. “Leave, Hanno!” he wills his subject. If Hanno never leaves, he will have nothing to write about. And Hanno, lazy in his imagination, finally stirs. Our seminarian writes:

The voyage took about thirty-seven days before Hanno decided to turn back at a point which has been greatly disputed, but which is now generally believed to be around Sherbro Island off Sierra Leone or Cape Palmas . . . There is no description of the return trip.

In fact the details of the journey are vague to the extent that it has been suggested that Hanno intentionally confused them. This has to do with Carthaginian hegemony—and a desire to befuddle Greek competitors. Hanno, like Laocoon, knew not to trust the Greeks.

The Greeks are powerful adversaries.

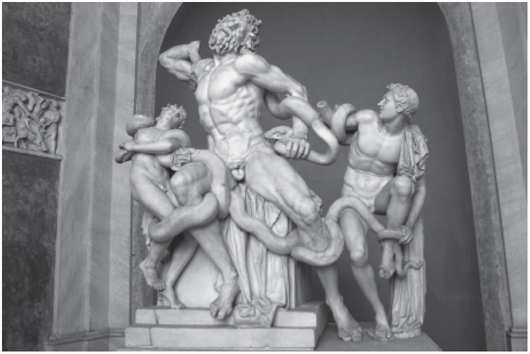

The seminarian looks at the picture of the sculpture of Laocoön in his book on Pliny. He reads what Pliny has to say about it, “it was to be preferred to all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced.”

He remembers Father Tedeschi, an art historian now returned to Rome, speaking about Michelangelo’s first view of Laocoön and His Sons. The year was 1506, and some Roman citizen, while digging around his vineyard on the Esquiline Hill, had discovered the entrance to a long-forgotten niche. One can only imagine his amazement as he peered into the darkness, blinking against it, until the group of figures—monumental Laocoön and his struggling sons bound together by writhing serpents—thrust their unspent anguish upon the Renaissance. And Michelangelo, who no doubt standing there and processing Laocoön’s torqued torso and blistering muscles, the expression evident not only in the pained faces of the figures but in every finger digit and calf tendon, thought to himself, The Greeks are

powerful adversaries. In this particular case, the Greeks being Agesandros, Polydoros, and Athanadoros of Rhodes, to whom Pliny attributes the sculpture.

I would go further to guess that Michelangelo, sweeping back to Trastevere and the ongoing torments of the pope—who had enlisted the Florentine to paint his chapel ceiling—swung between elation and annoyance at this feat of marble. Gone was the eternal complacency of the Apollo Belvedere, which he had skillfully bested with his David’s prolonged internal struggle, balanced against the splinter of time before action. This Laocoön was a composition that spun under the force of gaze, that pitted man against monster, his best self against his worst, his spiritual against his physical, and all the while under the eyes of gods who, worse than indifferent, were determined to do him in. As is often the response of artists who admire the work of others, this sculpture—this Laocoön, by three dead Greeks—seemed to have been expelled from the earth to spite him. As surely as Minerva sent her snakes to snare the priest, so had his God chosen to reveal the statue, miraculously torn from this cleft of the earth, and—a miracle, considering the march of time—all in one piece, as torment.

“Not to torment me,” thought Michelangelo, “to do me in!”

What will he pit against this statue?

What will the Renaissance have to stand against this work of ancients?

How can the present engage its ticking, slipping second against all that has gone before it?

“No wonder I have headaches and constipation,” says Michelangelo. “God damn those Greeks!”

“And Carthaginians!” adds the seminarian. Why engage the classical world? It’s not as if the hegemony of the Greeks is still an issue, nor do we stare past the Pillars of Hercules with awe and ignorance. There is Morocco and Mauritania and just more. What was it like for Hanno, who with his bronze tablet addressed a section of world where land bled to water and water to sky?

The seminarian’s eyes wander across the picture of Saint Ignatius again. He feels that he should fall upon his knee and offer his pencil. Would God take it if he stated, “Being scholar or saint is not my thing. I’d like to try soldiering”?

But someone has entered the library and is shuffling on leather soles among the stacks. Our seminarian closes the picture of the Laocoön, snaps the covers upon its distracting influence, not wanting to be discovered so entranced by something other than his paper. He looks at his notes. The first section is the introduction—clearly a good place to start—but he’s not altogether sure what he’s introducing. Maybe he should move to the next section, Pliny on Hanno, which is—if nothing else—where the intriguing matter will be placed. Pliny, writing five centuries after the time of Hanno, writes of the Carthaginian explorer three times. Our seminarian glances over his notes, flips back to the history, and writes:

In the final passage, Hanno, Poenorum imperator, is said to have reached the Gorgades Islands, where he came upon the people with hair all over their bodies, whom the Periplus calls

—gorillas, but whom Pliny refers to as Gorgons.

V. Monsters

The seminarian is under the impression that these hairy people were neither gorillas, nor gorgons, but rather pygmies. Much of Hanno’s information came from the Lixitae, and their word, “gorel” was a broad term for describing diminutive man-like creatures. The term could refer to a baboon, or a pygmy, or maybe even a dwarf. It is a term based on size, probably refined by familiarity—or in the case of this term, the absence of familiarity. Of course, now he’s merely positing.

But what if . . . of course, Hanno wrote in Punic. And he is translating out of the Greek into English in much the same way that, at some point, some like-minded Greek translated out of the Punic. But a Greek would not have used the word “gorilla” for what we now refer to as gorillas. Aristotle provided neat, fixed terms. For ape, he had  , pithikos; for baboon,

, pithikos; for baboon,  , kinokephalos; for monkey,

, kinokephalos; for monkey,  , kivos. So why use “gorilla,” should Hanno not be encountering something new?

, kivos. So why use “gorilla,” should Hanno not be encountering something new?

But what if Hanno was making it all up? Hanno writes of rivers and tracts of land in constant blaze, islands within islands, a fire-spewing mountain that seemed to touch the sky. Pliny has his fanciful unicorn moments, and Hanno might too. The seminarian looks at the Periplus and reads:

. . . and in this lake another island, full of savage people, the greater part of whom were women, whose bodies were hairy, and whom our interpreters called Gorillæ. Though we pursued the men, we could not seize any of them; but all fled from us, escaping over the precipices, and defending themselves with stones.

This did not sound like a gorilla to him. Didn’t gorillas stand their ground, beat their chests, roar? Or was this a vestigial belief left over from his Saturday viewings of Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan as he subjugated leopards, lions, gorillas too, and the truth, in the admirable pursuit of firing up the imaginations of young boys and bored housewives? He returns to the text.

Three women were however taken; but they attacked their conductors with their teeth and hands, and could not be prevailed upon to accompany us. Having killed them, we flayed them, and brought their skins with us to Carthage.

Were they human or animal? Attacking with teeth and hands sounds human. Having hairy, flay-worthy skins does not. Can these characteristics stand side by side?

The seminarian sifts through his stack of scholarship: the Frenchman who says that volcanoes appear and disappear in the course of history; the American woman who says that there might well have been gorillas in that region at that time: scholars searching for a possible reality to be—or to have been—reflected in the Periplus of Hanno. Hanno is undeniably vague. An infinite number of stories can be read into what he provides—extant only in its Greek translation—which has had its own wandering around: first brought west in the fifteenth century by a cardinal, most likely from Constantinople, in the decade after the city’s fall to the Turks, then passed from a Basel convent to a Protestant scholar during the Reformation, then—as a result of the Thirty Years’ War—carted off as Catholic booty to the Vatican, and now—in replica—before him on his desk in Shrub Oak, New York.

How many people have approached this document of 630 words and found volumes within it? How many words wash up against that original telling—conceived to neatly fit upon a bronze tablet—approaching and approaching in hopeful, scholarly erosion? Could this ever lay bare the truth?

Or are all these people, these scholars, attempting to find a reality to fit this tale? From this fiction, will they find a fact? Will they invent one? From this hairy gorilla, will they create a pygmy prototype or a migration of apes? A missing link? Is this scholarship? What is his paper trying to do?

Is he also composing reality from art?

“Mister Murray,” comes a voice. It is Father O’Donnell, himself an ancient, with one foot already in the afterlife. The old priest smiles benignly and possibly senilely, but if this is one of his earthbound days, he’ll be razor sharp. “How is your paper coming?”

“It started out well,” begins the seminarian, “and now I no longer know the purpose of scholarship.”

“Excellent,” says the old priest. He pats the seminarian’s head, then shuffles back to lurk behind reference.

“Excellent,” repeats the seminarian quietly. Is this one of Father O’Donnell’s days of senility or lucidity? He weighs the options and admits to himself that it could be either. Our seminarian has no idea whether he is sinking into a maudlin ignorance or achieving enlightenment. He looks at his translation—a solid, acceptable endeavor, that, turning words into other words. Or maybe it’s not, but the last thing he needs is another great abstracting truth to wrestle with.

His eye dawdles over the page, resting at the final passage: “. . . an island like the former, having a lake, and in this lake another island . . .”

“Islands within islands,” he repeats to himself. And then an insight. He will not argue with Pliny, he will embrace him. He will write about Pliny, and who’s the other guy who has so much to say on Hanno? Arrian. There’s his paper.

THE PERIPLUS OF HANNO

ACCORDING TO PLINY AND ARRIAN

Not according to me, he thinks. He’s carting boulders, not making mountains. He’s creating another lake in which to put all the other islands and lakes and islands.

VI. Extant

Pliny seems to have a handle on Hanno, although he hasn’t checked his facts. He seems to think that Hanno sailed from Cades to Arabia—Pliny’s convinced that Hanno circumnavigated Africa—a fact that is contradicted in the Periplus itself, which states that the party was forced to return. Hanno concludes: “We did not sail farther on, our provisions failing us.” The seminarian makes a note to address this discrepancy, which suggests either that Pliny did not have an account of the Periplus as he wrote, that it had been a while since Pliny had read the account, or that Pliny found it a much better story should Hanno have actually have traveled from Cerne (somewhere just past the Pillars of Hercules) all the way back to Arabia.

Was Pliny making his life impossible or giving him something to write about?

Our seminarian knows that Pliny’s great contribution is his Historia Naturalis, and that although he cannot always count on Pliny to be right, neither can he count on him to be wrong. Pliny is right maybe half the time factually, and all the time culturally. He’s more interesting when he’s wrong, when he writes of owl-eyed Albanians with flaming-red night vision, or King Pyrrhus who, with his swollen big toe, has the ability to heal all manner of ills. And accuracy had a different meaning then. Preserving knowledge in print was what excited Pliny—putting everything down—and had he not, we would have lost our gold-mining griffins of the far north. All that would remain is our goats and horses and sheep that present themselves now much as they did then: in a field rather than in the imagination. It’s still a tremendous accomplishment, even if he relied on others to supply the information, and had a judgment-impairing affection for the weird animal and odd cultural practice.

Ironically, the one event that Pliny is famous for actually having witnessed, he never had a chance to write about. This was the cataclysmic eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, which cautioned the outlying communities first with a cloud that appeared like “a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out into a sort [sic] of branches.” Pliny, hearing of the cloud, decided it merited a closer view. He launched his galleys from where he was staying in Misenum and headed across the Bay of Naples. This short journey, initially envisioned as one of scholarship and perhaps journalism, developed poignancy as the danger of the erupting volcano became impossible to ignore. Pliny was attempting to rescue people from Stabiae when he was overwhelmed with poisonous gases. Pliny suffocated. Two days after the eruption, his body was found, still, yet seemingly unharmed: the effect of toxic fumes.

What account we have of that fateful event in Pliny (the Elder)’s life is provided by his nephew, Pliny the Younger, who witnessed his uncle’s fatal embarkation but had the good luck to stay ashore. And this is what remains of Pliny’s journalistic urge—his death, and a rather good account of what went down, furnished in a letter from his nephew to Tacitus.

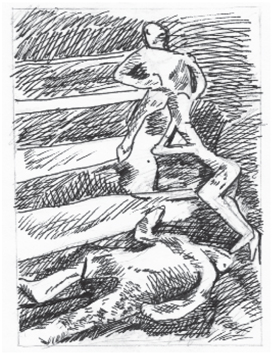

There, in the book, by the account of Pliny’s death, our seminarian sees a drawing of a plaster cast of three citizens of Pompeii, captured in their last moment, upon a set of stairs. He finds something artful about the composition rendered in quick frenetic lines, something aesthetic in how the geometric shadow of the steps offsets the rough human forms upon it. The three bodies form an L-shape, with the top-most figure seated, almost

lying on his back. The second figure forms the angle of the L, knees pulled up, his head sheltering beneath the thigh of his friend. And the third figure—the base of the L—is passed out facedown, a hand resting on the step above, as if he has never given up hope of reaching his destination: Sleeping Beauty forms, frozen in AD 79. They carry that moment with them, tacking it directly to our own—a pleat dissolving the years that separate the instant of their death from this of his viewing.

What would Michelangelo have had to say about it? Would he have been moved by this confrontation with the ancients? Would this interaction with capricious and uncaring gods—a grouping of three figures—without the skill of Polydoros, Athanadoros, and Agesandros to intervene—have moved him? Would Michelangelo have been as moved by people as by art? Is The People on the Stairs any less art than the Laocoön? What is the role of intention in art?

He thinks of one story: eruption, stairs, asphyxiation. And the other: Laocoön of the venom-filled fillets. Laocoön and his sons: extant in Virgil. The people on the stairs: extant in plaster. But in the end it’s only impression: the gorgeous grouping of the people on the stairs achieves what it does, like the Laocoön, through artificial appeal.

The seminarian looks up at the clock. He has only another hour to work today and after that it’s dinner and litanies and meditation. He looks at his paper—Pliny and Arrian on Hanno—and wonders if it’s possible to get some sort of digression on the nature of art in there, which he decides is impossible. But it does amuse him, and he needs to amuse himself: all this time alone intended to make one dialogue with God often has the added effect of making one dialogue with oneself, as if there were another of him seated beside, cracking jokes and laughing in turn.

“Enough,” says the seminarian, and he forces himself back to the Periplus. “Start at the beginning,” he wills himself, and reads Hanno’s opening line yet again.

“It was decreed by the Carthaginians, that Hanno should undertake a voyage beyond the Pillars of Hercules . . .”

VII. The Pillars of Hercules

Always the Pillars of Hercules! How tidy to have lived in the ancient world, where these pillars stood as literal markers between known and unknown, where so little was understood and recorded that one, standing upon the Rock of Gibraltar, could say, “Here is known!”—then point off into the North Atlantic and say, “There is unknown!” The Pillars of Hercules were the edge of the world, the ancients being a little more complicated than men in the Age of Exploration. One sailed through the edge of the world and into the unknown, rather than off the edge of the world and into oblivion. He remembers studying something about the Pillars of Hercules somewhere, a picture exists in his mind: two pillars and a galleon sailing through it. Of course, this looks nothing like the actual pillars—Hercules would never have created anything so baldly architectural and smooth. Instead, there is the Rock of Gibraltar and its corresponding Moroccan mountain—either the Monte Hacho in Ceuta or Morocco’s Jebel Musa.

Our seminarian wonders, despondently, whether such pillars still exist. Or has everything worthwhile been observed and catalogued, illustrated and recorded? Is scholarship a desperate attempt to fling up more pillars—more barriers between known and unknown—only to sail immediately through? Is it necessary to create the unknown? Our seminarian closes his eyes and imagines himself sailing through these pillars, from a world of cool green and blue into one of heated red and orange.

And then he imagines looking back and seeing his youthful self, the moment suspended as if viewed within a crystal ball: his cheek lying on an open page, his fingers loosely holding the pencil, his life unspooling ahead of him as he blinks against the dust of books and wonders what could possibly be important or unimportant. He is that young. The thought that he himself is a history, that the passage of time will be recorded in his face, his limbs, his slower heart pushing blood through the tributaries of his body, it all seems impossibly distant. Impossible.

VIII. The Golden Triangle

And here, in northern Thailand, the heat is formidable, but as a man who has worked and studied much of his life in Asia—near forty years—he is accustomed to it. He is taking a vanload of philosophy students from the University of Southern Maine wandering around Thailand on a voyage of discovery, mostly concerned with Buddhism. The students find the heat intense, the Thais (who are not intense) intense, even the food. He amuses himself by thinking of what it must be for them to live minute to minute in such a state of stimulation. He sees one young man snapping pictures of children, some girls looking at woven goods—bags and blankets—for which they will pay too much.

“Doctor Murray,” says one girl. “Why is it called the Golden Triangle?”

“Well, famously, because of the opium trade. But we will say that we are here because it is the place where Thailand, Burma, and Laos all meet. And for that it is worth looking at.”

The girl, smart enough but too practical for scholarship, looks first to the left with frank suspicion, then back over her shoulder. What can he teach this person, who has never had a question that she did not want answered?

“So the borders are right around here?”

He nods patiently.

“What’s the river?”

“That’s the Mekong. The confluence of the Ruak and Mekong is not far from here.”

“Oh,” she says, not impressed. “And what’s over there?”

She points toward Burma, and that is probably the answer that would satisfy her. She points to the west. She points to the West from the East. He knows the response cold, but then he doesn’t. He remembers being a sailor on a ship and the earth bowling up beneath him. He remembers living west, the sound of books slammed shut, the approach and loss of car radio music, popular music, coming over the seminary wall as he walked between buildings. He remembers being young. And then suddenly he remembers all, as if his entire memory has become suspended before him—this moment the portal to everything that has gone before. The world spins back and back, unleashing a pool of wrinkled event.

“Doctor Murray,” she says, “Doctor Murray.” And she looks concerned.

The sky is more white than blue and he wonders if it is always like that, and, if it is, why he has never noticed it before.

“Doctor Murray,” she says again.

“Over there?” he says.

She nods, but she’s forgotten her question.

He gestures with conviction. “Over there? Over there is everything.”