In September 1941, William McNeill was drafted into the U.S. Army. He spent several months in basic training, which consisted mostly of marching around the drill field in close formation with a few dozen other men. At first McNeill thought the marching was just a way to pass the time, because his base had no weapons with which to train. But after a few weeks, when his unit began to synchronize well, he began to experience an altered state of consciousness:

Words are inadequate to describe the emotion aroused by the prolonged movement in unison that drilling involved. A sense of pervasive well-being is what I recall; more specifically, a strange sense of personal enlargement; a sort of swelling out, becoming bigger than life, thanks to participation in collective ritual.1

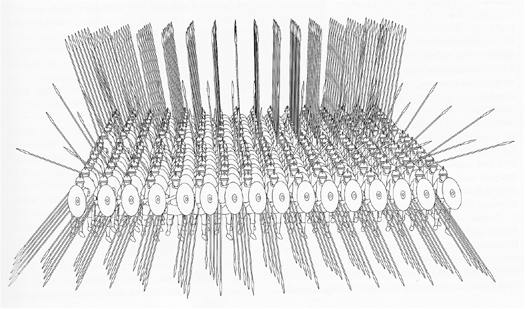

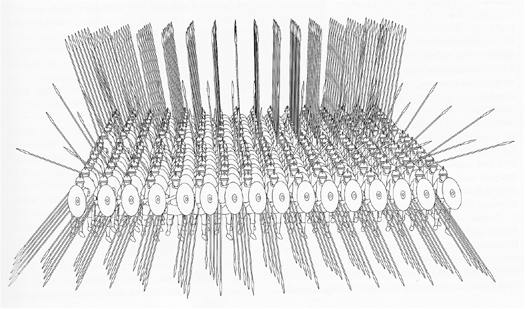

McNeill fought in World War II and later became a distinguished historian. His research led him to the conclusion that the key innovation of Greek, Roman, and later European armies was the sort of synchronous drilling and marching the army had forced him to do years before. He hypothesized that the process of “muscular bonding”—moving together in time—was a mechanism that evolved long before the beginning of recorded history for shutting down the self and creating a temporary superorganism. Muscular bonding enabled people to forget themselves, trust each other, function as a unit, and then crush less cohesive groups. Figure 10.1 shows the superorganism that Alexander the Great used to defeat much larger armies.

FIGURE 10.1. The Macedonian phalanx. (photo credit 10.1)

McNeill studied accounts of men in battle and found that men risk their lives not so much for their country or their ideals as for their comrades-in-arms. He quoted one veteran who gave this example of what happens when “I” becomes “we”:

Many veterans who are honest with themselves will admit, I believe, that the experience of communal effort in battle … has been the high point of their lives.… Their “I” passes insensibly into a “we,” “my” becomes “our,” and individual fate loses its central importance.… I believe that it is nothing less than the assurance of immortality that makes self sacrifice at these moments so relatively easy.… I may fall, but I do not die, for that which is real in me goes forward and lives on in the comrades for whom I gave up my life. 2

In the last chapter, I suggested that human nature is 90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee. We are like chimps in being primates whose minds were shaped by the relentless competition of individuals with their neighbors. We are descended from a long string of winners in the game of social life. This is why we are Glauconians, usually more concerned about the appearance of virtue than the reality (as in Glaucon’s story about the ring of Gyges).3

But human nature also has a more recent groupish overlay. We are like bees in being ultrasocial creatures whose minds were shaped by the relentless competition of groups with other groups. We are descended from earlier humans whose groupish minds helped them cohere, cooperate, and outcompete other groups. That doesn’t mean that our ancestors were mindless or unconditional team players; it means they were selective. Under the right conditions, they were able to enter a mind-set of “one for all, all for one” in which they were truly working for the good of the group, and not just for their own advancement within the group.

My hypothesis in this chapter is that human beings are conditional hive creatures. We have the ability (under special conditions) to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves (temporarily and ecstatically) in something larger than ourselves. That ability is what I’m calling the hive switch. The hive switch, I propose, is a group-related adaptation that can only be explained “by a theory of between-group selection,” as Williams said.4 It cannot be explained by selection at the individual level. (How would this strange ability help a person to outcompete his neighbors in the same group?) The hive switch is an adaptation for making groups more cohesive, and therefore more successful in competition with other groups.5

If the hive hypothesis is true, then it has enormous implications for how we should design organizations, study religion, and search for meaning and joy in our lives.6 Is it true? Is there really a hive switch?

When Europeans began to explore the world in the late fifteenth century, they brought back an extraordinary variety of plants and animals. Each continent had its own wonders; the diversity of the natural world was vast beyond imagination. But reports about the inhabitants of these far-flung lands were, in some ways, more uniform. European travelers to every continent witnessed people coming together to dance with wild abandon around a fire, synchronized to the beat of drums, often to the point of exhaustion. In Dancing in the Streets: A History of Collective Joy, Barbara Ehrenreich describes how European explorers reacted to these dances: with disgust. The masks, body paints, and guttural shrieks made the dancers seem like animals. The rhythmically undulating bodies and occasional sexual pantomimes were, to most Europeans, degrading, grotesque, and thoroughly “savage.”

The Europeans were unprepared to understand what they were seeing. As Ehrenreich argues, collective and ecstatic dancing is a nearly universal “biotechnology” for binding groups together.7 She agrees with McNeill that it is a form of muscular bonding. It fosters love, trust, and equality. It was common in ancient Greece (think of Dionysus and his cult) and in early Christianity (which she says was a “danced” religion until dancing in church was suppressed in the Middle Ages).

But if ecstatic dancing is so beneficial and so widespread, then why did Europeans give it up? Ehrenreich’s historical explanation is too nuanced to summarize here, but the last part of the story is the rise of individualism and more refined notions of the self in Europe, beginning in the sixteenth century. These cultural changes accelerated during the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. It is the same historical process that gave rise to WEIRD culture in the nineteenth century (that is, Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic).8 As I said in chapter 5, the WEIRDer you are, the more you perceive a world full of separate objects, rather than relationships. The WEIRDer you are, the harder it is to understand what those “savages” were doing.

Ehrenreich was surprised to discover how little help she could get from psychology in her quest to understand collective joy. Psychology has a rich language for describing relationships among pairs of people, from fleeting attractions to ego-dissolving love to pathological obsession. But what about the love that can exist among dozens of people? She notes that “if homosexual attraction is the love that ‘dares not speak its name,’ the love that binds people to the collective has no name at all to speak.”9

Among the few useful scholars she found in her quest was Emile Durkheim. Durkheim insisted that there were “social facts” that were not reducible to facts about individuals. Social facts—such as the suicide rate or norms about patriotism—emerge as people interact. They are just as real and worthy of study (by sociology) as are people and their mental states (studied by psychology). Durkheim didn’t know about multilevel selection and major transitions theory, but his sociology fits uncannily well with both ideas.

Durkheim frequently criticized his contemporaries, such as Freud, who tried to explain morality and religion using only the psychology of individuals and their pairwise relationships. (God is just a father figure, said Freud.) Durkheim argued, in contrast, that Homo sapiens was really Homo duplex, a creature who exists at two levels: as an individual and as part of the larger society. From his studies of religion he concluded that people have two distinct sets of “social sentiments,” one for each level. The first set of sentiments “bind[s] each individual to the person of his fellow-citizens: these are manifest within the community, in the day-to-day relationships of life. These include the sentiments of honour, respect, affection and fear which we may feel towards one another.”10 These sentiments are easily explained by natural selection operating at the level of the individual: just as Darwin said, people avoid partners who lack these sentiments.11

But Durkheim noted that people also had the capacity to experience another set of emotions:

The second are those which bind me to the social entity as a whole; these manifest themselves primarily in the relationships of the society with other societies, and could be called “inter-social.” The first [set of emotions] leave[s] my autonomy and personality almost intact. No doubt they tie me to others, but without taking much of my independence from me. When I act under the influence of the second, by contrast, I am simply a part of a whole, whose actions I follow, and whose influence I am subject to.12

I find it stunning that Durkheim invokes the logic of multilevel selection, proposing that a new set of social sentiments exists to help groups (which are real things) with their “inter-social” relationships. These second-level sentiments flip the hive switch, shut down the self, activate the groupish overlay, and allow the person to become “simply a part of a whole.”

The most important of these Durkheimian higher-level sentiments is “collective effervescence,” which describes the passion and ecstasy that group rituals can generate. As Durkheim put it:

The very act of congregating is an exceptionally powerful stimulant. Once the individuals are gathered together, a sort of electricity is generated from their closeness and quickly launches them to an extraordinary height of exaltation.13

In such a state, “the vital energies become hyperexcited, the passions more intense, the sensations more powerful.”14 Durkheim believed that these collective emotions pull humans fully but temporarily into the higher of our two realms, the realm of the sacred, where the self disappears and collective interests predominate. The realm of the profane, in contrast, is the ordinary day-to-day world where we live most of our lives, concerned about wealth, health, and reputation, but nagged by the sense that there is, somewhere, something higher and nobler.

Durkheim believed that our movements back and forth between these two realms gave rise to our ideas about gods, spirits, heavens, and the very notion of an objective moral order. These are social facts that cannot be understood by psychologists studying individuals (or pairs) any more than the structure of a beehive could be deduced by entomologists examining lone bees (or pairs).

Collective effervescence sounds great, right? Too bad you need twenty-three friends and a bonfire to get it. Or do you? One of the most intriguing facts about the hive switch is that there are many ways to turn it on. Even if you doubt that the switch is a group-level adaptation, I hope you’ll agree with me that the switch exists, and that it generally makes people less selfish and more loving. Here are three examples of switch flipping that you might have experienced yourself.

In the 1830s, Ralph Waldo Emerson delivered a set of lectures on nature that formed the foundation of American Transcendentalism, a movement that rejected the analytic hyperintellectualism of America’s top universities. Emerson argued that the deepest truths must be known by intuition, not reason, and that experiences of awe in nature were among the best ways to trigger such intuitions. He described the rejuvenation and joy he gained from looking at the stars, or at a vista of rolling farmland, or from a simple walk in the woods:

Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.15

Darwin records a similar experience in his autobiography:

In my journal I wrote that whilst standing in midst of the grandeur of a Brazilian forest, “it is not possible to give an adequate idea of the higher feelings of wonder, admiration, and devotion which fill and elevate the mind.” I well remember my conviction that there is more in man than the breath of his body.16

Emerson and Darwin each found in nature a portal between the realm of the profane and the realm of the sacred. Even if the hive switch was originally a group-related adaptation, it can be flipped when you’re alone by feelings of awe in nature, as mystics and ascetics have known for millennia.

The emotion of awe is most often triggered when we face situations with two features: vastness (something overwhelms us and makes us feel small) and a need for accommodation (that is, our experience is not easily assimilated into our existing mental structures; we must “accommodate” the experience by changing those structures).17 Awe acts like a kind of reset button: it makes people forget themselves and their petty concerns. Awe opens people to new possibilities, values, and directions in life. Awe is one of the emotions most closely linked to the hive switch, along with collective love and collective joy. People describe nature in spiritual terms—as both Emerson and Darwin did—precisely because nature can trigger the hive switch and shut down the self, making you feel that you are simply a part of a whole.

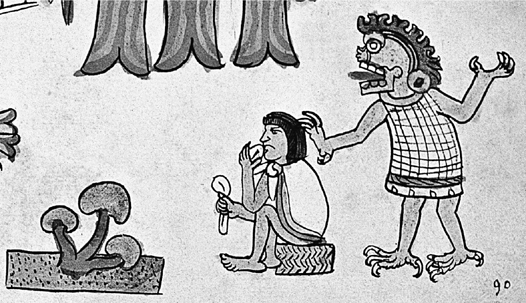

When Cortés captured Mexico in 1519, he found the Aztecs practicing a religion based on mushrooms containing the hallucinogen psilocybin. The mushrooms were called teonanacatl—literally “God’s flesh” in the local language. The early Christian missionaries noted the similarity of mushroom eating to the Christian Eucharist, but the Aztec practice was more than a symbolic ritual. Teonanacatl took people directly from the profane to the sacred realm in about thirty minutes.18 Figure 10.2 shows a god about to grab hold of a mushroom eater, from a sixteenth-century Aztec scroll. Religious practices north of the Aztecs focused on consumption of peyote, harvested from a cactus containing mescaline. Religious practices south of the Aztecs focused on consumption of ayahuasca (Quechua for “spirit vine”), a brew made from vines and leaves containing DMT (dimethyltriptamine).

These three drugs are classed together as hallucinogens (along with LSD and other synthetic compounds) because the class of chemically similar alkaloids in such drugs induces a range of visual and auditory hallucinations. But I think these drugs could just as well be called Durkheimogens, given their unique (though unreliable) ability to shut down the self and give people experiences they later describe as “religious” or “transformative.”19

Most traditional societies have some sort of ritual for transforming boys into men and girls into women. It’s usually far more grueling than a bar mitzvah; it frequently involves fear, pain, symbolism of death and rebirth, and a revelation of knowledge by gods or elders.20 Many societies used hallucinogenic drugs to catalyze this transformation. The drugs flip the hive switch and help the selfish child disappear. The person who returns from the other world is then treated as a morally responsible adult. One anthropological review of such rites concludes: “These states were induced to heighten learning and to create a bonding among members of the cohort group, when appropriate, so that individual psychic needs would be subsumed to the needs of the social group.”21

FIGURE 10.2. An Aztec mushroom eater, about to be whisked away to the realm of the sacred. Detail from the Codex Magliabechiano, CL.XIII.3, sixteenth century. (photo credit 10.2)

When Westerners take these drugs, shorn of all rites and rituals, they don’t usually commit to any group, but they often have experiences that are hard to distinguish from the “peak experiences” described by the humanistic psychologist Abe Maslow.22 In one of the few controlled experiments, done before the drugs were made illegal in most Western countries, twenty divinity students were brought together in the basement chapel of a church in Boston.23 All took a pill, but for the first twenty minutes, nobody knew who had taken psilocybin and who had taken niacin (a B vitamin that gives people a warm, flushed feeling). But by forty minutes into the experiment, it was clear to all. The ten who took niacin (and who had been the first to feel something happening) were stuck on Earth wishing the other ten well on their fantastic voyage.

The experimenters collected detailed reports from all participants before and after the study, as well as six months later. They found that psilocybin had produced statistically significant effects on nine kinds of experiences: (1) unity, including loss of sense of self, and a feeling of underlying oneness, (2) transcendence of time and space, (3) deeply felt positive mood, (4) a sense of sacredness, (5) a sense of gaining intuitive knowledge that felt deeply and authoritatively true, (6) paradoxicality, (7) difficulty describing what had happened, (8) transiency, with all returning to normal within a few hours, and (9) persisting positive changes in attitude and behavior. Twenty-five years later, Rick Doblin tracked down nineteen of the twenty original subjects and interviewed them.24 He concluded that “all psilocybin subjects participating in the long-term follow-up, but none of the controls, still considered their original experience to have had genuinely mystical elements and to have made a uniquely valuable contribution to their spiritual lives.” One of the psilocybin subjects recalled his experience like this:

All of a sudden I felt sort of drawn out into infinity, and all of a sudden I had lost touch with my mind. I felt that I was caught up in the vastness of Creation.… Sometimes you would look up and see the light on the altar and it would just be a blinding sort of light and radiations.… We took such an infinitesimal amount of psilocybin, and yet it connected me to infinity.

Rock music has always been associated with wild abandon and sexuality. American parents in the 1950s often shared the horror of those seventeenth-century Europeans faced with the ecstatic dancing of the “savages.” But in the 1980s, British youth mixed together new technologies to create a new kind of dancing that replaced the individualism and sexuality of rock with more communal feelings. Advances in electronics brought new and more hypnotic genres of music, such as techno, trance, house, and drum and bass. Advances in laser technology made it possible to bring spectacular visual effects into any party. And advances in pharmacology made a host of new drugs available to the dancing class, particularly MDMA, a variant of amphetamine that gives people long-lasting energy, along with heightened feelings of love and openness. (Revealingly, the colloquial name for MDMA is ecstasy.) When some or all of these ingredients were combined, the result was so deeply appealing that young people began converging by the thousands for all-night dance parties, first in the United Kingdom and then, in the 1990s, throughout the developed world.

There’s a description of a rave experience in Tony Hsieh’s autobiography Delivering Happiness. Hsieh (pronounced “Shay”) is the CEO of the online retailer Zappos.com. He made a fortune at the age of twenty-four when he sold his start-up tech company to Microsoft. For the next few years Hsieh wondered what to do with his life. He had a small group of friends who hung out together in San Francisco. The first time Hsieh and his “tribe” (as they called themselves) attended a rave, it flipped his hive switch. Here is his description:

What I experienced next changed my perspective forever.… Yes, the decorations and lasers were pretty cool, and yes, this was the largest single room full of people dancing that I had ever seen. But neither of those things explained the feeling of awe that I was experiencing … As someone who is usually known as being the most logical and rational person in a group, I was surprised to find myself swept with an overwhelming sense of spirituality—not in the religious sense, but a sense of deep connection with everyone who was there as well as the rest of the universe. There was a feeling of no judgment.… Here there was no sense of self-consciousness or feeling that anyone was dancing to be seen dancing.… Everyone was facing the DJ, who was elevated up on a stage.… The entire room felt like one massive, united tribe of thousands of people, and the DJ was the tribal leader of the group.… The steady wordless electronic beats were the unifying heartbeats that synchronized the crowd. It was as if the existence of individual consciousness had disappeared and been replaced by a single unifying group consciousness.25

Hsieh had stumbled into a modern version of the muscular bonding that Ehrenreich and McNeill had described. The scene and the experience awed him, shut down his “I,” and merged him into a giant “we.” That night was a turning point in his life; it started him on the path to creating a new kind of business embodying some of the communalism and ego suppression he had felt at the rave.

There are many other ways to flip the hive switch. In the ten years during which I’ve been discussing these ideas with my students at UVA, I’ve heard reports of people getting “turned on” by singing in choruses, performing in marching bands, listening to sermons, attending political rallies, and meditating. Most of my students have experienced the switch at least once, although only a few had a life-changing experience. More commonly, the effects fade away within a few hours or days.

Now that I know what can happen when the hive switch gets flipped in the right way at the right time, I look at my students differently. I still see them as individuals competing with each other for grades, honors, and romantic partners. But I have a new appreciation for the zeal with which they throw themselves into extracurricular activities, most of which turn them into team players. They put on plays, compete in sports, rally for political causes, and volunteer for dozens of projects to help the poor and the sick in Charlottesville and in faraway countries. I see them searching for a calling, which they can only find as part of a larger group. I now see them striving and searching on two levels simultaneously, for we are all Homo duplex.

If the hive switch is real—if it’s a group-level adaptation designed by group-level selection for group binding—then it must be made out of neurons, neurotransmitters, and hormones. It’s not going to be a spot in the brain—a clump of neurons that humans have and chimpanzees lack. Rather, it will be a functional system cobbled together from preexisting circuits and substances reused in slightly novel ways to produce a radically novel ability. In the last ten years there’s been an avalanche of research on the two26 most likely building materials of this functional system.27

If evolution chanced upon a way to bind people together into large groups, the most obvious glue is oxytocin, a hormone and neurotransmitter produced by the hypothalamus. Oxytocin is widely used among vertebrates to prepare females for motherhood. In mammals it causes uterine contractions and milk letdown, as well as a powerful motivation to touch and care for one’s children. Evolution has often reused oxytocin to forge other kinds of bonds. In species in which males stick by their mates or protect their own offspring, it’s because male brains were slightly modified to be more responsive to oxytocin.28

In people, oxytocin reaches far beyond family life. If you squirt oxytocin spray into a person’s nose, he or she will be more trusting in a game that involves transferring money temporarily to an anonymous partner.29 Conversely, people who behave trustingly cause oxytocin levels to increase in the partner they trusted. Oxytocin levels also rise when people watch videos about other people suffering—at least among those who report feelings of empathy and a desire to help.30 Your brain secretes more oxytocin when you have intimate contact with another person, even if that contact is just a back rub from a stranger.31

What a lovely hormone! It’s no wonder the press has swooned in recent years, dubbing it the “love drug” and the “cuddle hormone.” If we could put oxytocin into the world’s drinking water, might there be an end to war and cruelty?

Unfortunately, no. If the hive switch is a product of group selection, then it should show the signature feature of group selection: parochial altruism.32 Oxytocin should bond us to our partners and our groups, so that we can more effectively compete with other groups. It should not bond us to humanity in general.

Several recent studies have validated this prediction. In one set of studies, Dutch men played a variety of economic games while sitting alone in cubicles, linked via computers into small teams.33 Half of the men had been given a nasal spray of oxytocin, and half got a placebo spray. The men who received oxytocin made less selfish decisions—they cared more about helping their group, but they showed no concern at all for improving the outcomes of men in the other groups. In one of these studies, oxytocin made men more willing to hurt other teams (in a prisoner’s dilemma game) because doing so was the best way to protect their own group. In a set of follow-up studies, the authors found that oxytocin caused Dutch men to like Dutch names more and to value saving Dutch lives more (in trolley-type dilemmas). Over and over again the researchers looked for signs that this increased in-group love would be paired with increased out-group hate (toward Muslims), but they failed to find it.34 Oxytocin simply makes people love their in-group more. It makes them parochial altruists. The authors conclude that their findings “provide evidence for the idea that neurobiological mechanisms in general, and oxytocinergic systems in particular, evolved to sustain and facilitate within-group coordination and cooperation.”

The second candidate for sustaining within-group coordination is the mirror neuron system. Mirror neurons were discovered accidentally in the 1980s when a team of Italian scientists began inserting tiny electrodes into individual neurons in the brains of Macaque monkeys. The researchers were trying to find out what some individual cells were doing in a region of the cerebral cortex that they knew controls fine motor movements. They discovered that there were some neurons that fired rapidly only when the monkey made a very specific movement, such as grasping a nut between thumb and forefinger (versus, say, grabbing the nut with the entire hand). But once they had these electrodes implanted and hooked up to a speaker (so that they could hear the rate of firing), they began to hear firing noises at odd times, such as when a monkey was perfectly still and it was the researcher who had just picked up something with his thumb and forefinger. This made no sense because perception and action were supposed to occur in separate regions of the brain. Yet here were neurons that didn’t care whether the monkey was doing something or watching someone else do it. The monkey seemed to mirror the actions of others in the same part of its brain that it would use to do those actions itself.35

Later work demonstrated that most mirror neurons fire not when they see a specific physical movement but when they see an action that indicates a more general goal or intention. For example, watching a video of a hand picking up a cup from a clean table, as if to bring it to the person’s mouth, triggers a mirror neuron for eating. But the exact same hand movement and the exact same cup picked up from a messy table (where a meal seems to be finished) triggers a different mirror neuron for picking things up in general. The monkeys have neural systems that infer the intentions of others—which is clearly a prerequisite for Tomasello’s shared intentionality36—but they aren’t yet ready to share. Mirror neurons seem designed for the monkeys’ own private use, either to help them learn from others or to help them predict what another monkey will do next.

In humans the mirror neuron system is found in brain regions that correspond directly to those studied in macaques. But in humans the mirror neurons have a much stronger connection to emotion-related areas of the brain—first to the insular cortex, and from there to the amygdala and other limbic areas.37 People feel each other’s pain and joy to a much greater degree than do any other primates. Just seeing someone else smile activates some of the same neurons as when you smile. The other person is effectively smiling in your brain, which makes you happy and likely to smile, which in turn passes the smile into someone else’s brain.

Mirror neurons are perfectly suited for Durkheim’s collective sentiments, particularly the emotional “electricity” of collective effervescence. But their Durkheimian nature comes out even more clearly in a study led by the neuroscientist Tania Singer.38 Subjects first played an economic game with two strangers, one of whom played nicely while the other played selfishly. In the next part of the study, subjects’ brains were scanned while mild electric shocks were delivered randomly to the hand of the subject, the hand of the nice player, or the hand of the selfish player. (The other players’ hands were visible to the subject, near her own while she was in the scanner.) Results showed that subjects’ brains responded in the same way when the “nice” player received a shock as when they themselves were shocked. The subjects used their mirror neurons, empathized, and felt the other’s pain. But when the selfish player got a shock, people showed less empathy, and some even showed neural evidence of pleasure.39 In other words, people don’t just blindly empathize; they don’t sync up with everyone they see. We are conditional hive creatures. We are more likely to mirror and then empathize with others when they have conformed to our moral matrix than when they have violated it.40

From cradle to grave we are surrounded by corporations and things made by corporations. What exactly are corporations, and how did they come to cover the Earth? The word itself comes from corpus, Latin for “body.” A corporation is, quite literally, a superorganism. Here is an early definition, from Stewart Kyd’s 1794 Treatise on the Law of Corporations:

[A corporation is] a collection of many individuals united into one body, under a special denomination, having perpetual succession under an artificial form, and vested, by policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual.41

This legal fiction, recognizing “a collection of many individuals” as a new kind of individual, turned out to be a winning formula. It let people place themselves into a new kind of boat within which they could divide labor, suppress free riding, and take on gigantic tasks with the potential for gigantic rewards.

Corporations and corporate law helped England pull out ahead of the rest of the world in the early days of the industrial revolution. As with the transition to beehives and city-states, it took a while for the new superorganisms to work out the kinks, perfect the form, and develop effective defenses against external attacks and internal subversion. But once those problems were addressed, there was explosive growth. During the twentieth century, small businesses got pushed to the margins or to extinction as corporations dominated the most lucrative markets. Corporations are now so powerful that only national governments can restrain the largest of them (and even then it’s only some governments, and some of the time).

It is possible to build a corporation staffed entirely by Homo economicus. The gains from cooperation and division of labor are so vast that large companies can pay more than small businesses and then use a series of institutionalized carrots and sticks—including expensive monitoring and enforcement mechanisms—to motivate self-serving employees to act in ways the company desires. But this approach (sometimes called transactional leadership)42 has its limits. Self-interested employees are Glauconians, far more interested in looking good and getting promoted than in helping the company.43

In contrast, an organization that takes advantage of our hivish nature can activate pride, loyalty, and enthusiasm among its employees and then monitor them less closely. This approach to leadership (sometimes called transformational leadership)44 generates more social capital—the bonds of trust that help employees get more work done at a lower cost than employees at other firms. Hivish employees work harder, have more fun, and are less likely to quit or to sue the company. Unlike Homo economicus, they are truly team players.

What can leaders do to create more hivish organizations? The first step is to stop thinking so much about leadership. One group of scholars has used multilevel selection to think about what leadership really is. Robert Hogan, Robert Kaiser, and Mark van Vugt argue that leadership can only be understood as the complement of followership.45 Focusing on leadership alone is like trying to understand clapping by studying only the left hand. They point out that leadership is not even the more interesting hand; it’s no puzzle to understand why people want to lead. The real puzzle is why people are willing to follow.

These scholars note that people evolved to live in groups of up to 150 that were relatively egalitarian and wary of alpha males (as Chris Boehm said).46 But we also evolved the ability to rally around leaders when our group is under threat or is competing with other groups. Remember how the Rattlers and the Eagles instantly became more tribal and hierarchical the instant they discovered the presence of the other group?47 Research also shows that strangers will spontaneously organize themselves into leaders and followers when natural disasters strike.48 People are happy to follow when they see that their group needs to get something done, and when the person who emerges as the leader doesn’t activate their hypersensitive oppression detectors. A leader must construct a moral matrix based in some way on the Authority foundation (to legitimize the authority of the leader), the Liberty foundation (to make sure that subordinates don’t feel oppressed, and don’t want to band together to oppose a bullying alpha male), and above all, the Loyalty foundation (which I defined in chapter 7 as a response to the challenge of forming cohesive coalitions).

Using this evolutionary framework, we can draw some direct lessons for anyone who wants to make a team, company, school, or other organization more hivish, happy, and productive. You don’t need to slip ecstasy into the watercooler and then throw a rave party in the cafeteria. The hive switch may be more of a slider switch than an on-off switch, and with a few institutional changes you can create environments that will nudge everyone’s sliders a bit closer to the hive position. For example:

• Increase similarity, not diversity. To make a human hive, you want to make everyone feel like a family. So don’t call attention to racial and ethnic differences; make them less relevant by ramping up similarity and celebrating the group’s shared values and common identity.49 A great deal of research in social psychology shows that people are warmer and more trusting toward people who look like them, dress like them, talk like them, or even just share their first name or birthday.50 There’s nothing special about race. You can make people care less about race by drowning race differences in a sea of similarities, shared goals, and mutual interdependencies.51

• Exploit synchrony. People who move together are saying, “We are one, we are a team; just look how perfectly we are able to do that Tomasello shared-intention thing.” Japanese corporations such as Toyota begin their days with synchronous companywide exercises. Groups prepare for battle—in war and sports—with group chants and ritualized movements. (If you want to see an impressive one in rugby, Google “All Blacks Haka.”) If you ask people to sing a song together, or to march in step, or just to tap out some beats together on a table, it makes them trust each other more and be more willing to help each other out, in part because it makes people feel more similar to each other.52 If it’s too creepy to ask your employees or fellow group members to do synchronized calisthenics, perhaps you can just try to have more parties with dancing or karaoke. Synchrony builds trust.

• Create healthy competition among teams, not individuals. As McNeill said, soldiers don’t risk their lives for their country or for the army; they do so for their buddies in the same squad or platoon. Studies show that intergroup competition increases love of the in-group far more than it increases dislike of the out-group.53 Intergroup competitions, such as friendly rivalries between corporate divisions, or intramural sports competitions, should have a net positive effect on hivishness and social capital. But pitting individuals against each other in a competition for scarce resources (such as bonuses) will destroy hivishness, trust, and morale.

Much more could be said about leading a hivish organization.54 Kaiser and Hogan offer this summary of the research literature:

Transactional leadership appeals to followers’ self-interest, but transformational leadership changes the way followers see themselves—from isolated individuals to members of a larger group. Transformational leaders do this by modeling collective commitment (e.g., through self-sacrifice and the use of “we” rather than “I”), emphasizing the similarity of group members, and reinforcing collective goals, shared values, and common interests.55

In other words, transformational leaders understand (at least implicitly) that human beings have a dual nature. They set up organizations that engage, to some degree, the higher level of that nature. Good leaders create good followers, but followership in a hivish organization is better described as membership.

Great leaders understand Durkheim, even if they’ve never read his work. For Americans born before 1950, you can activate their Durkheimian higher nature by saying just two words: “Ask not.” The full sentence they’ll hear in their minds comes from John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address. After calling on all Americans to “bear the burden of a long twilight struggle”—that is, to pay the costs and take the risks of fighting the cold war against the Soviet Union—Kennedy delivered one of the most famous lines in American history: “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

The yearning to serve something larger than the self has been the basis of so many modern political movements. Here’s another brilliantly Durkheimian appeal:

[Our movement rejects the view of man] as an individual, standing by himself, self-centered, subject to natural law, which instinctively urges him toward a life of selfish momentary pleasure; it sees not only the individual but the nation and the country; individuals and generations bound together by a moral law, with common traditions and a mission which, suppressing the instinct for life closed in a brief circle of pleasure, builds up a higher life, founded on duty, a life free from the limitations of time and space, in which the individual, by self-sacrifice, the renunciation of self-interest … can achieve that purely spiritual existence in which his value as a man consists.

Inspiring stuff, until you learn that it’s from The Doctrine of Fascism, by Benito Mussolini.56 Fascism is hive psychology scaled up to grotesque heights. It’s the doctrine of the nation as a superorganism, within which the individual loses all importance. So hive psychology is bad stuff, right? Any leader who tries to get people to forget themselves and merge into a team pursuing a common goal is flirting with fascism, no? Asking your employees to exercise together—isn’t that the sort of thing Hitler did at his Nuremberg rallies?

Ehrenreich devotes a chapter of Dancing in the Streets to refuting this concern. She notes that ecstatic dancing is an evolved biotechnology for dissolving hierarchy and bonding people to each other as a community. Ecstatic dancing, festivals, and carnivals invariably erase or invert the hierarchies of everyday life. Men dress as women, peasants pretend to be nobles, and leaders can be safely mocked. When it’s all over and people have returned to their normal social stations, those stations are a bit less rigid, and the connections among people in different stations are a bit warmer.57

Fascist rallies, Ehrenreich notes, were nothing like this. They were spectacles, not festivals. They used awe to strengthen hierarchy and to bond people to the godlike figure of the leader. People at fascist rallies didn’t dance, and they surely didn’t mock their leaders. They stood around passively for hours, applauding when groups of soldiers marched by, or cheering wildly when the dear leader arrived and spoke to them.58

Fascist dictators clearly exploited many aspects of humanity’s groupish psychology, but is that a valid reason for us to shun or fear the hive switch? Hiving comes naturally, easily, and joyfully to us. Its normal function is to bond dozens or at most hundreds of people together into communities of trust, cooperation, and even love. Those bonded groups may care less about outsiders than they did before their bonding—the nature of group selection is to suppress selfishness within groups to make them more effective at competing with other groups. But is that really such a bad thing overall, given how shallow our care for strangers is in the first place? Might the world be a better place if we could greatly increase the care people get within their existing groups and nations while slightly decreasing the care they get from strangers in other groups and nations?

Let’s imagine two nations, one full of small-scale hives, one devoid of them. In the hivish nation, let’s suppose that most people participate in several cross-cutting hives—perhaps one at work, one at church, and one in a weekend sports league. At universities, most students join fraternities and sororities. In the workplace, most leaders structure their organizations to take advantage of our groupish overlay. Throughout their lives, citizens regularly enjoy muscular bonding, team building, and moments of self-transcendence with groups of fellow citizens who may be different from them racially, but with whom they feel deep similarity and interdependence. This bonding is often accompanied by the excitement of intergroup competition (as in sports and business), but sometimes not (as in church).

In the second nation, there’s no hiving at all. Everyone cherishes their autonomy and respects the autonomy of their fellow citizens. Groups form only to the extent that they advance the interests of their members. Businesses are led by transactional leaders who align the material interests of employees as closely as possible with the interests of the company, so that if everyone pursues their self-interest, the business will thrive. In this non-hivish nation you’ll find families and plenty of friendships; you’ll find altruism (both kin and reciprocal). You’ll find all the stuff described by evolutionary psychologists who doubt that group selection occurred, but you’ll find no evidence of group-related adaptations such as the hive switch. You’ll find no culturally approved or institutionalized ways to lose yourself in a larger group.

Which nation do you think would score higher on measures of social capital, mental health, and happiness? Which nation will produce more successful businesses and a higher standard of living?59

When a single hive is scaled up to the size of a nation and is led by a dictator with an army at his disposal, the results are invariably disastrous. But that is no argument for removing or suppressing hives at lower levels. In fact, a nation that is full of hives is a nation of happy and satisfied people. It’s not a very promising target for takeover by a demagogue offering people meaning in exchange for their souls. Creating a nation of multiple competing groups and parties was, in fact, seen by America’s founding fathers as a way of preventing tyranny.60 More recently, research on social capital has demonstrated that bowling leagues, churches, and other kinds of groups, teams, and clubs are crucial for the health of individuals and of a nation. As political scientist Robert Putnam put it, the social capital that is generated by such local groups “makes us smarter, healthier, safer, richer, and better able to govern a just and stable democracy.”61

A nation of individuals, in contrast, in which citizens spend all their time in Durkheim’s lower level, is likely to be hungry for meaning. If people can’t satisfy their need for deep connection in other ways, they’ll be more receptive to a smooth-talking leader who urges them to renounce their lives of “selfish momentary pleasure” and follow him onward to “that purely spiritual existence” in which their value as human beings consists.

When I began writing The Happiness Hypothesis, I believed that happiness came from within, as Buddha and the Stoic philosophers said thousands of years ago. You’ll never make the world conform to your wishes, so focus on changing yourself and your desires. But by the time I finished writing, I had changed my mind: Happiness comes from between. It comes from getting the right relationships between yourself and others, yourself and your work, and yourself and something larger than yourself.

Once you understand our dual nature, including our groupish overlay, you can see why happiness comes from between. We evolved to live in groups. Our minds were designed not only to help us win the competition within our groups, but also to help us unite with those in our group to win competitions across groups.

In this chapter I presented the hive hypothesis, which states that human beings are conditional hive creatures. We have the ability (under special circumstances) to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves (temporarily and ecstatically) in something larger than ourselves. I called this ability the hive switch. The hive switch is another way of stating Durkheim’s idea that we are Homo duplex; we live most of our lives in the ordinary (profane) world, but we achieve our greatest joys in those brief moments of transit to the sacred world, in which we become “simply a part of a whole.”

I described three common ways in which people flip the hive switch: awe in nature, Durkheimian drugs, and raves. I described recent findings about oxytocin and mirror neurons that suggest that they are the stuff of which the hive switch is made. Oxytocin bonds people to their groups, not to all of humanity. Mirror neurons help people empathize with others, but particularly those that share their moral matrix.

It would be nice to believe that we humans were designed to love everyone unconditionally. Nice, but rather unlikely from an evolutionary perspective. Parochial love—love within groups—amplified by similarity, a sense of shared fate, and the suppression of free riders, may be the most we can accomplish.