History may inspire, caution, encourage, and constrain later generations. With respect to housing, the attitudes, institutional arrangements, and physical fabric we now confront have all evolved from earlier encounters with housing the City’s residents. The following historical images illustrate the circumstances of real people in a variety of physical environments that reflect the entire social spectrum, from the unhoused and under-housed, to the modestly housed, and the distinctly over-housed.

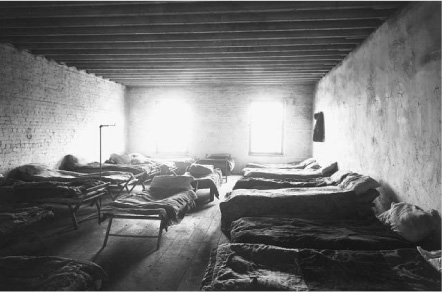

Front Street Flop House, c. 1912

Labelled “10 Cent Lodging House on Front Street,” this photograph was taken by the City’s official photographer, Arthur Goss, in about 1912, to help illustrate the connection between poor housing and poor health. Dr Charles Hastings, the crusading Medical Officer of Health at the time, had some success in driving this point home and in promoting significant public health advances.

CTA: RG 8, Series 4, Sub-series 32, Item6

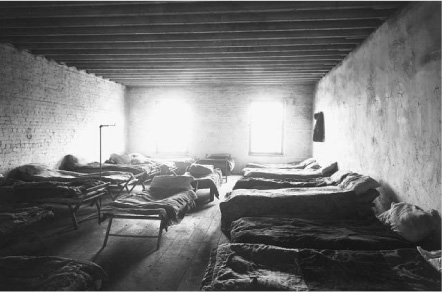

York Street Boarding House, c. 1912

Ever the consummate documentary photographer, Arthur Goss managed to persuade these Macedonian immigrants to come out of their tightly packed rooms to pose for his lens. Note the heating pipe snaking along the hallway ceiling, the battered wainscoting, and the decorative wallpaper adding a layer to paper-thin walls. The fact that the lodgings were “since improved with modern conveniences” was recorded on the back of the photograph. Just what these “modern conveniences” might have been is unknown.

CTA: RG 8, Series 4, Sub-series 32, Item3

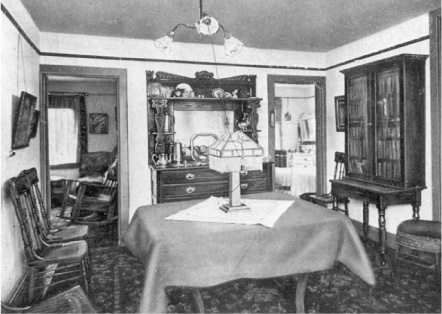

Mrs Agnew’s Boarding House, 244 Jarvis Street, c. 1886

No longer standing, 244 Jarvis was a common type of housing for its time: a brick, bay and gable, semi-detached house of modest proportions.

CTA: Fonds 80, File 3

Eating Watermelon, 244 Jarvis Street, c. 1886

Mrs Catherine Agnew was a middle-class widow who, according to City records, bought and moved to 244 Jarvis in around 1875. Whether she was a teacher before her physician husband’s death is not known, but she certainly taught at Winchester School in nearby Cabbagetown while residing at 244 Jarvis. In 1886 she was living with two named children (bank clerk Robert and law student John), as well as nine other unidentified boarders, some of whom may be enjoying the watermelon treat captured in this lighthearted photograph.

CTA: Fonds 80, File 4

Spruce Court “Play Court,” c. 1914

In response to the inhumane housing found in such infamous parts of Toronto as “The Ward” (i.e., the area bounded by Queen, University, College and Yonge), the City’s first government-sponsored housing was built at 74 to 86 Spruce Street in Cabbagetown. Constructed for working people, Spruce Court could hardly have been more different from the Ward and its ilk: solid, well-built, brick buildings; open, grassy common spaces; individual entrances; airy, well-ventilated, well-lit interiors; modern gas stoves and electric fixtures; and careful detailing throughout. This photograph, looking south toward the old Toronto General Hospital on Gerrard Street, shows a group of children playing on the still-new greensward, supervised by adults from stoops, porches, and verandahs looking out over the common area. At this time, Spruce Court contained 32 cottage flats and 6 six-room houses.

CTA: SC 18

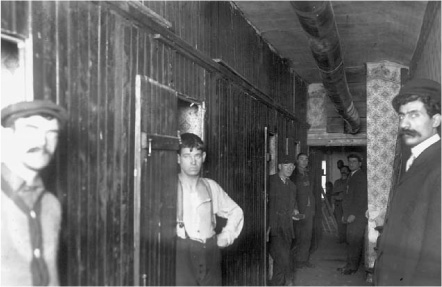

Spruce Court, Living Area, c. 1914

“Sanitary conveniences, adequate bedroom accommodation and domestic privacy are the primary requirements for proper housing,” proclaimed the Toronto Housing Company’s 1915 publication, Cottage Flats, where this photograph by William James first appeared. At that time, “cottage flats” ranged in size from small, one-bedroom flats to four-bedroom, two-storey units, and monthly rents ran from $14.50 to $29.00, depending on size and location. This photograph shows the living room in one of the larger cottage flats at Spruce Court, furnished as a model suite. The layout and the furnishings reflect the aspirations of the Housing Company to house lower-income wage earners well.

Unfortunately, this early housing experiment was not a financial success. At a time when the average wage was still considerably under $15.00 a week the rents charged by the Toronto Housing Company proved too onerous for the target clientele. Just twenty years later, in the middle of the Great Depression, the Toronto Housing Company ceased operations. Fortunately, the physical fabric of the projects was neither razed nor renovated into oblivion. Spruce Court now operates as a successful City housing co-op.

CTA: SC 18, Item 26

Tea Time at 39 Huron Street, c. 1909

William James, the stern patriarch at the centre of this large family grouping, emigrated from England in 1906. By 1909 he was an established professional photographer and living in the first of his four Toronto homes, 39 Huron Street, a tiny, worker’s cottage located south of Grange Avenue. The James family lived in crowded conditions: here we see eleven people (and one cat) gathered around a foldout table in the corner of the kitchen/dining/living room. Still, all the proprieties are being observed: a proper English tea is set on a white tablecloth; solid furniture rings the room; knick-knacks are neatly displayed along the mantelpiece; leather-bound books are piled atop the highboy; and the loud waterlily wallpaper is decorated with an abundance of prints, photographs, and calendars. The building still stands and is still used for housing.

CTA: SC 244, Item 3554

Parlour Portrait, 697 Spadina Avenue, 1893

This parlour portrait is devoid of people, but full of information about both the house and its occupant. Although bigger than the James cottage and located in a more affluent neighbourhood, this Romanesque

Revival residence is still modestly proportioned. Through the string curtains one can see that the main staircase is a switchback, rather than a straight bank, and that the parlour and dining rooms open off either side of a small entrance hall, rather than directly into one another as in many semi-detached houses. The kitchen is tucked discreetly out of sight in the back.

As for the parlour itself, it speaks volumes about the activities, tastes, and even aspirations of its occupant, or possibly its real estate agent, since the first occupant, Stacey Lake, a Gutta-Percha Co. cashier had only just moved in about the time the photograph was taken. Everything is laid out and carefully displayed for the camera: the ubiquitous parlour piano and wildly popular stereoscopic viewer; a large, five-string banjo, and issues of Scribner’s. The lightly coloured walls lessen any claustrophobic feeling, and the stylish gasolier hangs ready to cast light whenever it’s needed. This residence still stands on the east side of Spadina Avenue, just south of Washington Avenue.

CTA: SC 128, Series 1, Item 1234

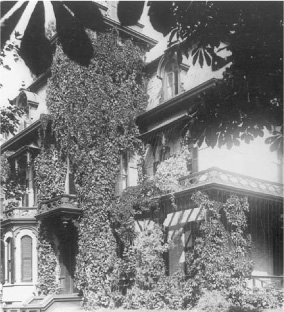

Blake Residence, 467–469 (formerly 397–399) Jarvis Street, c. 1880

The Hon. Edward Blake, who was the first Liberal Premier of Ontario (1870–71), purchased 397–399 Jarvis Street (“Humewood”) in 1879. Standing on the east side of tree-lined and ultra-fashionable Jarvis Street, Blake’s picturesque, Second Empire-cum-Italianate residence was actually a pair of semi-detached dwellings that he adapted according to the needs of his family. Walls were knocked out and filled in and front doors were shifted, rejigging both interiors and exteriors as deemed necessary. Blake also purchased the house immediately to the south for other members of his family. Now these large residences are occupied by businesses; accountants and small offices are in Humewood, and the Red Lion pub is in the house to the south.

CTA: SC 146, Item 2

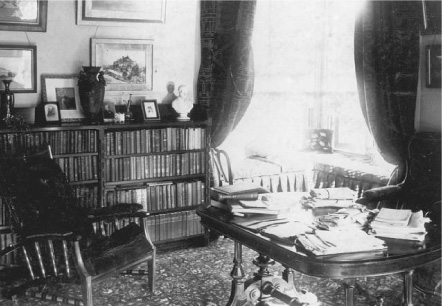

Blake’s Study, 467–469 Jarvis Street, c. 1880

Most photographs of Victorian interiors show highly decorated and over-stuffed spaces but this upstairs room looks comfortably lived in. Blake’s study gives the impression that the great man has just stepped out for a moment and will return shortly to work on the legal papers strewn across his desk. The sun-drenched window faces south, overlooking what is now the Red Lion and an empty chair appears to await the arrival of a statesman or favour-seeker to consult with the Liberal Leader.

CTA: SC 146, Item 11

Cumberland House, “Pendarvis,” 33 St George Street, late 1880s

Frederick W. Cumberland built “Pendarvis” between 1857 and 1860, while creating his near-by masterpiece, University College. “Pendarvis” was the first building on St George Street. It served as Cumberland’s home until his death in 1881 and is now generally known as Cumberland House.

The mansion was redesigned in 1883 by his partner, William Storm, and remained in residential use until the University of Toronto purchased the property in 1923. Since then, this handsome, mid-Victorian mansion has been renovated and put to new use several times. It now functions as a lively International Students Centre.

The most obvious changes since Cumberland’s day concern the siting of the building, which is now hemmed in on three sides and nearly invisible from any point except St George Street. When it was first built, Cumberland House was entered from the east (now a parking lot); it looked southward across fields toward the distant city (a view now blocked by the Wallberg Engineering Building); and it turned its back on the new St George Street. At the time of this photograph, the main entrance appears to be in the centre of the south facade and a delicate verandah extends along the building’s entire length. The house was still visually prominent and approachable from several directions. Today the main entrance is on the west side, once the back of the house.

CTA: SC 155, Item 1

Hall, Cumberland House, 33 St George Street, c. 1890

No photographs survive of the original Cumberland interior; however, there are some taken by J. Bruce when the house was about 30 years old. In contrast, the latest decoration of the International Students Centre displays elements of neoclassical restraint. For example, the walls of a meeting room running along the south facade are painted creamy yellow, and the ceiling, decorative plaster, mouldings, pillars, and elegantly wrought radiator covers are all painted white – a far cry from the late Victorian opulence shown in this photograph. Here we see a large, but dark and claustrophobic Victorian hallway. Statues, urned plants, and heavy mirrors crowd the passage. Every wall and ceiling is hung with patterned paper. Even an internal doorway is draped with fashionably heavy swags.

Sally Gibson

CTA: SC 155, Item 4