Rosedale, which has loomed large on Toronto’s mythic landscape for nearly 150 years as home to many wealthy and well-known people, occupies an impressive 620 acres near the centre of the city, and contains over 2,200 dwellings. Bounded on the west by Yonge Street, the CPR rail line on the north, the Don Valley on the east, and by Bloor Street and the Rosedale Valley on the south, Rosedale is split by the Silver Creek or Park Drive ravine into a northern and southern part.

South Rosedale had its origins in the 1854 subdivision of part of Sheriff William B. Jarvis’s estate on the edge of Yorkville Village to create 61 villa lots within a pattern of winding streets that responded to the adjacent ravines rather than a grid. This plan, highly unusual for the time, originated with Jarvis’s surveyor, J. Stoughton Dennis. Later, between 1877 and 1896, it was extended over three other adjacent but smaller estates. From these four estates only one great-house survives (5 Drumsnab Road, 1835; altered 1856). Villas dating from the first wave of building in Jarvis’s subdivision include 23 Rosedale Road (1857; altered 1911), 124 Park Road (1857), “Glen Hurst” (1866) on the grounds of Branksome Hall Girls School, 27 Rosedale Road (1871), and 3 Meredith Crescent (1876). When Rosedale, as part of Yorkville, was annexed to the City in 1883, a few new houses stood on Elm Avenue and South Drive, but not many elsewhere. Along the ravine that separated South Rosedale from the near-empty lands to the north, three large mansions had taken up sentry-like positions flanking Glen Road and Elm Avenue. Today only shady grounds and handsome gates (1903) of “Craigleigh” survive to recall that trio.

Between 1884 and 1904 development was slow and scattered. No more than three dozen houses were constructed then, of which 2 Dale Avenue (1887), 128 Park Road (1893), and a terrace at 141–147 Roxborough Street East (c.1890) are good examples. The great boom in South Rosedale, which accounts for much of its present architectural character, didn’t occur until 1904–14, when a couple of hundred dwellings were built. Streets like Chestnut Park were filled up then with big, brick houses, many in an Arts-and-Crafts style, by architects like Burke, Horwood and White (No. 1, 1915), A.E. Boultbee (No. 20, 1905–06), S.H. Townsend (No. 24, 1905), and E.J. Lennox (No. 48, 1903). What was for many years the area’s only apartment house was erected at 75 Crescent Road in 1912. At that time, too, more boulevard trees were planted that now contribute so much to Rosedale’s garden-suburb appearance.

Meanwhile, North Rosedale had begun to grow. An iron bridge erected in the early 1880s to carry Glen Road over to the Silver Creek ravine did little to stimulate building there until shortly before the First World War. Development was helped by the decision in 1911 to erect “Chorley Park,” the palatial and now-demolished official residence of Ontario’s Lieutenant Governor, on a 14-acre site overlooking the Don Valley between Roxborough Drive and Summerhill Avenue. About that time, a few large houses were erected on Binscarth Road, Highland Avenue and Beaumont Road, and several smaller ones on streets north of Summerhill Avenue to the CPR right-of-way. But there was no building on the lands between, where the Lacrosse Grounds (now Rosedale Park) and St Andrew’s College were located, until after the school removed to Aurora in the 1920s.

Thanks to redevelopment of the George Estate as Old George Place, and other smaller projects, North Rosedale boasts some excellent examples of modern-period architecture by Ron Thom (4 Old George, 1971), John B. Parkin (3 Old George, 1959), and Barton Myers (51 Roxborough Drive, 1972).

EJR

In some ways, Rosedale led a charmed life in the post-war period, only to suffer more recently with the architectural excesses of Big Money. When Mount Pleasant Road was extended through the area to link up with Jarvis Street, only two houses and a worn-out school were demolished. A spate of apartment building in the 1950s, taking advantage of large ravine lots, was brought under control before much damage was done to the area’s character. And the Crosstown Expressway, linking the Don Valley to Davenport Road, died on the drawing board. Whether Rosedale will emerge with its integrity intact from the current wave of redevelopment, characterized by a taste for neo-Georgian country houses squeezed onto city lots, remains to be seen.

Stephen A. Otto

Sherbourne Street at Ancroft Place

Architects, Shepard and Calvin

Completed 1927

Toronto has few 75-year old housing projects with the urbanity of Ancroft Place. Conceived in 1926 as a way to redevelop a large, old estate with a minimal frontage on the east side of North Sherbourne Street above Bloor, it consists of 21 houses grouped into three blocks. Five dwellings face the main street (Sherbourne), while 16 others have numbers on Ancroft Place, a side street close to the south edge of the property. The units vary in size from six to nine rooms. Behind the buildings a lane leads to the service entrances and heated, private garages that are attached to each unit. The architects for the complex, Shepard and Calvin of Toronto, succeeded brilliantly in creating an informal pattern of clustered residences in the English cottage style, where none looks directly into the windows of a near neighbour. While appearing as separate dwellings, the houses are in fact in a single ownership and share a common heating plant.

EJR

Stephen A. Otto

592 Sherbourne Street

Architect, David Roberts Jr

Completed c.1883

The Selby Hotel was originally home to the Gooderham family, distillers extraordinaire. A prime example of Victorian architecture, it features wraparound verandahs, gables, bargeboards, dormer windows, and exceptional stone and brickwork. The architect, David Roberts Jr, was the same architect who designed the mansion at 504 Jarvis Street in 1891, the Flatiron building at Front and Wellington (the original head office for Gooderham and Worts), and the York Club on the northeast corner of St George and Bloor.

Sherbourne Street, like the parallel Church and Jarvis streets, was at one time the most fashionable street in Toronto. But the area experienced a decline as other residential neighbourhoods, such as the Annex and Rosedale, grew. Upkeep was especially onerous on these large properties. Only in the 1980s did signs of revitalization begin to be seen, as the once elegant mansions became commercial spaces incorporating offices, restaurants, rooming houses, and convenience stores. Despite the fact that it presently serves as a budget hotel, the Selby is fortunate to have largely maintained the scale of its original spaces, although the visitor has to work to imagine it as a luxury residence.

EJR

The Gooderhams lived in the house from 1894 to 1910, after which their home became the early incarnation of Branksome Hall, a private girls’ school, from 1910 to 1913. Thereafter, the building became known as the Selby Hotel, so named as it is situated on the corner of Sherbourne and Selby streets.

A classic H-plan configuration was added to the western portion of the property to increase capacity. The Selby served as an early budget hotel and was seconded as a home for World War II officers. At one time Ernest Hemingway stayed at the Selby with his wife Hadley, who occupied an adjoining suite next to her husband. By the 1970s the Selby had become seedy as prostitutes were using its main floor rooms for clients.

The Selby continued to slip into decline until Rick Stenhouse purchased the hotel in 1984 and went about the process of restoring and preserving the property to its original character. The suites in the original home were restored to their 15-foot ceiling heights, and mouldings, doorways, and fireplace mantels were all restored. The cast-iron fence bordering the property is not original but it is similar to the fence that protected the original Gooderham home. The slate roof was restored in the mid-1980s. Today, the well-known gay bar “Boots” occupies the basement of the hotel and the Selby attracts both locals and tourists who are drawn to the offerings of the neighbouring gay community.

Ian Chodikoff

79 Charles Street East

Quadrangle Architects Limited

Completed 1994

This project was designed within the restrictive building envelope of a previously approved condominium tower for the site. The building is a co-operative housing development, which includes housing for persons with AIDS. The project consists of a 66 suite, 16-storey, stepped point tower on Church Street and a 20 unit, four-storey, walk-up apartment along the rear lane, with a landscaped courtyard between the two structures. The tower has a strong cornice line at the fourth floor that ties together the two buildings, and the rear building reinforces a City policy aimed at improving public safety by putting life onto the back lanes.

• Quadrangle Architects

Leslie M. Klein

North side of Wellesley Street, between

Sherbourne and Wellesley Place

Architect, Henry Bowyer Lane

Completed 1847; demolished 1964

The most obvious sign that remains of Homewood is a bend in the road. To most people travelling on Wellesley Street East, this gentle curve is an odd and inexplicable diversion in Toronto’s otherwise straightforward grid system. It isn’t a surveyor’s error (an incorrect meeting of two grids), but an indication of the pattern of early settlement in the area. The land between Queen and Bloor streets had been originally laid out as large estate lots, called park lots, which were gradually subdivided to accommodate urban development. The Allen family owned this park lot, and it was the younger Allen, George, who built his villa Homewood on this site. Homewood, which had been built in 1847 to the designs of the noted architect Henry Bowyer Lane, remained standing until 1964. In 1900, it was the first house in Toronto to have electricity, and when its grounds had been reduced to 4 1/2 acres, it was converted into the first Wellesley Hospital, which was formally opened by Sir Wilfrid Laurier in 1911.

The gentle curve in the road marked the gracious front yard of the estate. Homewood Avenue created a central, axial corridor from the house down to Allen Gardens, the horticultural grounds donated by the Allen family to the city as the central focus of their park lot development. This corridor continued further south as Pembroke Street, leading to Moss Park, the estate of George Allen’s father. This plan of linked gardens and estate lots with landscaped lawns, orchards, greenhouses and tennis courts gradually became the framework for the existing city fabric. It underlies this part of Toronto, like an almost forgotten memory, a dream of a pastoral city.

Michael McClelland

Bounded by Sherbourne, Howard,

Parliament and Wellesley streets

Architects, George Jarosz and

James Murray

Completed 1965-68

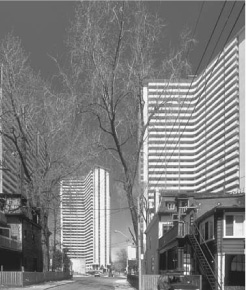

With a population of about 15,000 people on an area just over one fifth of a square kilometre, St James Town is probably the most densely populated piece of real estate in the whole of Canada. Not only are there a lot of people living in St James Town but they are a very mixed group of people and many are new immigrants (St Jamestown represents one of the major concentrations of new immigrants in the city). Rose Avenue Public School, the local school, boasts that it has the most diverse group of students anywhere in the Greater Toronto area. There are children here from dozens of different countries.

One of the unique aspects of St James Town in the Toronto context is that its 18 high-rise buildings are owned by a mix of public and private landlords. Four of the larger buildings are owned by Metro Toronto Housing Authority, and the other 14 buildings are privately owned. Many of the privately owned buildings were seen as “up market” addresses when they were first occupied in the 1960s. A number of them still boast swimming pools in their basements, although most have not been used for years.

EJR

St James Town is still seen by many of its residents as a good place to live, since it is centrally located, rents are affordable, and, although there is a paucity of recreational facilities within St James Town itself, the diversions of downtown are nearby. When the high-rise towers of St James Town were built in the early 1960s, they displaced the kind of housing that takes up much of the current South St. James Town, i.e. that area south of Wellesley and down to Carlton Street. Obviously, the displacement of detached houses, semi-detached houses, and row houses has had a marked effect on the urban landscape, and there was considerable protest against the change when it happened. Even today, many feel the scale of development is inappropriate. However, against this one must weigh the fact that many more people are now within easy access of the downtown area. And any discussion with the residents of St James Town will reveal that there are benefits to the high-rise life, not least of which are the views.

Jim Ward

1975, St James Town, a summer day. A group of swingers in bell bottoms, carrying beer and pizza, pop into one of the 30-storey-high or so apartments in the area to join a weekend swing party. These apartment buildings were occupied by young singles or couples who were proud to say, “Yeah, we live in St James Town!”

1999, St James Town, summer day. A group of young mothers, whose first language is not English, push their baby strollers to the corner of apartment 135, waiting for the school bus that will bring their children to a local Catholic school. They were talking about the break-in at Mrs Tan’s place, an apartment unit that was home to two adults and six children. When asked if they would bring their kids to one of the few playgrounds in the neighbourhood, most said, “Probably not, unless the place has other activities for the teenagers so that they won’t take over the playground.”

These are the concerns that inspired a group of 20 University of Toronto landscape architecture and architecture students to seek ways to help improve this neighbourhood. On February 9, 2000, the team led a group of 30 (residents, planners, and public officials), on a walk around the neighbourhood, recording their observations about the site and discussing ways to improve it. The following are some of the comments that were made:

“More lighting [is] needed and signs for the school kids on the road; people do not bring dogs [on a] leash and they poop all over the place.”

“When crossing the street at Wellesley and Ontario I’m asked questions [about drugs].”

Christina Tang

“[The service lane] looks very dangerous, puzzling, you don’t know where [it’s leading] to.”

“I think we should turn down all the fences and change the service lane into a park and put the community garden somewhere where everyone can use it.”

“We should apply for grants to hire the local teenagers to clean up litter and guard the park during the summer … This will use their energy positively, and educate them to care about their community.”

Yvonne Sze-Man Yuen

Bounded by Sherbourne, Wellesley, Parliament

and Gerrard streets

South St James Town retains much of the physical character that was once present in St James Town itself. The housing is mostly two-storey and of 19th-century vintage. Many houses have been rooming houses for several decades, one of the major landlords being the City of Toronto Department of Housing; which owns several clusters of rooming houses along Wellesley Street, Parliament Street, Prospect Street, and Carlton Street. These rooming houses accommodate several hundred low-income earners close to the downtown area. There are also several denser, affordable-housing developments in South St James Town; some are City-owned and the Hugh Garner Housing Cooperative forms an important presence in the northwestern corner of the area. In at least one case, a City-owned building has been made into a cooperative housing project.

EJR

Although only Parliament Street separates South St James Town from Cabbagetown to the east, South St James Town is markedly different in socioeconomic terms. In 1996, for example, median family incomes were less than half those in Cabbagetown. As with St James Town itself, this part of Toronto provides fairly low-cost housing in an area close to the city centre.

Jim Ward

Behold the lowly, but tall, residential high-rise building. A thousand buildings like this cover the city – a promotional booklet from the period proclaims that Toronto built over 200 buildings of this size in 1968 alone. These buildings are supreme examples of modern planning rationalism. To paraphrase Sprint Canada, they get “the most for the least.” The most people living on a plot of land with the least possible amount of material, that is. The material restrictions dictate a certain severity and optimum deployment, which results in a limited number of stylistic options – all of which have been played out around Toronto over time. One of the standard styles is “Rectilinear Classic”:

Stage I –

• Level the site of all that came before;

• Excavate and lay in as much parking as possible;

• Relay a thin layer of grass, and include soon-to-be-smelly stairwells poking out from below;

• Fence the site (optional);

• In the midst of this, situate a tower, slab walls aligning with the parking layout below;

• Extrude stories as required and/or allowed (whichever comes first); with absolute uniformity from bottom to top.

Stage 2 – consider options: How to deal with the balconies? What material for infilling the concrete frame? How should the building hit the ground? (Toronto architects are notoriously good at avoiding the relationship of building to ground.) How to deal with all the exposed concrete?

Rectilinear Classic makes the obvious choices:

• Symmetry, symmetry, symmetry;

• Solid balcony guards (solid appearance = clean appearance);

• Pinch the corners to take the bulk out (i.e., don’t put balconies at the end);

• Reveal the concrete structure by infilling the walls within the structural frame (why pay for covering the structure, and it adds visual interest);

It was within these parameters that the high-rise housing game of the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s was played. After 1980, the rules changed again. When is the last time you saw exposed concrete? Looking back from the 21st century, we now know these buildings, with all their faults and their energetic ideals, are now historic in their own right.

Ian Panabaker

56 Wellesley Street East

Built 1854–56

Addition: Architect, Paul Reuber

Completed 1986

Designed in 1983 and completed in 1986, this Lilliputian 18-unit apartment block was the third and final phase for the community-based Church-Isabella Residents’ Cooperative Inc. It was the first project of substance by its architect.

Paul Kane, famous for his 19th century oil paintings depicting North America’s native people, built a Georgian home on the site in 1856. Later, to please a more Victorian eye, a side bay window, a two-storey porch, and a peaked roofline were added. In the 1930s, the house was completely obscured by the construction of an addition to house a church for the deaf. A developer purchased the property in the mid-1970s, intending to build a high-rise structure. The church was demolished and, suddenly, the long-forgotten Kane house was again exposed to public view.

Community pressure prevented the ultimate destruction of the Kane house, and the City eventually purchased the property, transferring the developer’s density rights to an adjacent site. In 1983, after the house had suffered several years of vacant neglect, the Church Isabella Co-operative successfully answered a City proposal call with a scheme to lease the rear of the site for residential use and landscape the front as a public park.

Robert Mikel/THB

The front wing of the house has been renovated to contain multi-level three-bedroom units. The fire-damaged rear wing has been demolished to make way for a four-storey addition containing eight lower units with tiny rear gardens and eight upper units with roof terraces. Corridors on the first and third levels are singly loaded and have operable windows facing the park. There is a kitchen window surveying the corridor next to the front door of every unit. The front facade expresses the collective nature of the co-operative, while the rear expresses the individuality of each unit.

The rehabilitation of the Paul Kane house addressed three goals: it found a reuse for a historic building, provided affordable family housing close to a subway station, and created a public park in an area chronically short of green space.

Paul Reuber

Architect, Dermot J Sweeny

Conversion completed 1996

The recession of the early 1990s left many vacant or under-leased commercial buildings in the downtown. Office conversions to residential use became a City-supported developer’s rally – in mid-1995, according to the (old) City of Toronto’s Planning Department, there were at least 20 applications for conversions. Eight Wellesley Street East was one of the first conversions of a 1960s era, Miesian, curtain-walled, waffle-slabbed office building to an 81 unit condominium, and among one of the most successful. Directly across from 8 Wellesley Street, at 555 Yonge, there is a similarly proportioned building – a contemporary conversion – that is visually much less satisfying. One wonders whether, if the same developer had bought both, there might have been a twinned gateway to Wellesley Street East and the neighbourhoods beyond.

EJR

David Winterton

In a community such as Cabbagetown, it’s not surprising that the impetus for a Heritage Conservation District (HCD) came from the “grassroots.” After all, Cabbagetown has a well-established preservation association, a deep sense of community pride, and a unique architectural heritage often touted as “North America’s largest collection of Victorian homes.” Yet, in Toronto, HCDs are unusual – and a grassroots approach to creating them is even more unusual. So far, only four HCDs have been approved in the city, and all were “top-down initiatives” proposed and implemented by Heritage Toronto back in the “glory days” when staff and resources were plentiful.

In 1995, Peggy Kurtin, then President of the Cabbagetown Preservation Association, began working with a dedicated group of individuals to put together the initial study to establish the HCD. She says, “We knew it would be an uphill battle because it hadn’t been done this way before.” Fortunately, the volunteer group had enormous tenacity. The study had been limited to Metcalfe Street, one of the most charming and best-preserved streets in Cabbagetown. Metcalfe Street exudes a sense of cohesiveness, probably because it features a uniform style of wrought iron fencing due to a communal agreement in the past. In both a cultural sense and an architectural sense, Metcalfe Street was an excellent candidate for a HCD.

Although the volunteer group was delighted by the warm endorsement in official circles, a proposal was made to expand boundaries that also expanded the workload. Kurtin says, “Most people have no idea how time-consuming this process is – every single house in the area must be researched at the City Archives and cross-checked at the Registry Office, and then catalogued with a formal written description and photograph.” The project kept a corps of twelve volunteers working for months.

In addition to historical research, the process of gaining official status as an HCD brings many other challenges. One of the most delicate is what is sometimes called “managing the public process” – making sure that resident homeowners are well-informed and invited to provide their comments and express their concerns. The ideal goal is to gain unanimous support from homeowners in the area.

The delicate, and somewhat political issue, is homeowners’ rights. When an area becomes an HCD, homeowners must seek special approvals to make architectural alterations which must generally conform to the historical guidelines that have been established for the district. In the Metcalfe Street proposal, it was decided that guidelines would be limited to the exterior facades of the homes and the streetscape. In other words, homeowners would be free to make whatever interior renovations they wished, assuming they complied with standard building regulations. As part of the process, a Steering Committee was formed to include community representatives from each of the five streets in the expanded area, and representatives from key official sectors. Public meetings were held and went surprisingly smoothly. In fact, Kurtin says the only complaint they heard was from one homeowner outside of the proposed district, wondering why his home hadn’t been included!

Clearly, in the case of the proposed Metcalfe Street HCD, homeowners recognize there are many benefits, some of which are financial. Studies suggest that real estate values generally go up. In Toronto, municipal heritage staff offer grants for historic renovation and supply some cost-free advice and expertise.

Peggy Kurtin

Despite the enthusiasm for the Metcalfe Street HCD and unanimous support from all homeowners in the area, it is not yet an official reality. Assuming the proposal gets the right blessings along the way, it must still go to the Ontario Municipal Board for final approval.

As Kurtin says, “It’s an onerous process – not something you do lightly.” When asked why she has put so much time and energy into it, she says, “I chose to live here because I liked the character of the area. That’s what attracted me to the area. I don’t want that to change.”

Kathy Farrell

(previously known as

Sumach Street Terraces)

74–86 Spruce Street

Architects, Eden Smith and Sons

Completed 1913

Spruce Court represents the first deliberate attempt to create low-income public housing in Canada. It was the product of an early public and private partnership initiative, which identified the need for low-income housing, arranged for financing, and administered the project until 1980. Spruce Court is also notable because it exhibited the design attributes, architectural style, and high quality of construction usually associated with single-family housing.

Wins Bridgman

The complex is located at the corner of Spruce and Sumach streets, near Dundas and Parliament. Spruce Court comprises 78 various-sized flats in two- and three-storey buildings. All the flats have a front door and porch to the outside. They face either Spruce Street or Sumach Street, or face one of two courtyards open on one side to the street. The first half of the project formed the Sumach Street courtyard in 1913. The Spruce Street courtyard followed in 1926. Riverdale Courts, constructed in 1913, was a larger but similar project on Bain Avenue, also designed by the architectural firm Eden Smith and Sons.

The funding and planning for Spruce Court was arranged by the Toronto Housing Company (an earlier version of Cityhome) in 1913, in response to a need for rental housing closer to the industrial heart of the city. The effort involved a partnership between the business community and the Canadian Manufacturer’s Association, with the Toronto Board of Trade, the Guild of Civic Art, the Local Council of Women (who were especially concerned about the welfare of working single mothers), and the Toronto City Council.

Eden Smith (1858–1949) was a sought-after Toronto architect. Most of the 2,500 single-family houses he designed and constructed were built in the English Cottage Style. Concurrent with Spruce Court, for instance, Smith was involved in the planning of the site, and the architect for six notable houses, in what is known today as Wychwood Park.

The English Cottage Style used at Spruce Court evoked in the popular mind the image of a simple and domestic, country life. This romantic association took the form of steep shingled roofs, broad eaves, tall chimneys, brick and stucco walls, half- timbered gables, large roofed verandas, arched brick porches with stone steps, heavy wood front doors, and, within the site’s restrictions, verdant courtyards and gardens. Equally important to the character of the buildings are the quality of materials, for example, the solid wood doors, the heavy brass hardware, the stone thresholds in the porches and the play of voids and solids. The latter is created by the shadow in the porch archways, the roofed verandah, the shadowed eave on otherwise simple building volumes, and the large and divided windows with deep reveals. The interiors also contain enduring materials, such as hardwood floors, decorative wood mouldings, doglegged hardwood stairs, and plaster walls. Interior and exterior details and rich materials were used sparingly but to great purpose.

Wins Bridgman

The Spruce Court buildings were an immediate success with the new residents, and they continue to provide a rare level of domestic pleasure in public housing.

Wins Bridgman

77 Winchester Street,

39 and 43 Metcalfe Street

This 39-unit apartment building became a non-profit housing co-operative in 1981, after a high-spirited tenant battle with the owner and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC). Built in 1911, the former Hampton Mansions was a gracious, middle-class apartment house with fine chestnut woodwork, tiled gas fireplaces, large windows, good cross ventilation, and dumb-waiters connecting each unit to delivery areas in the basement. Hampton Mansions and a number of neighbouring properties on Winchester, Metcalfe, and Sackville streets had been assembled during the late 1960s and early 1970s by a developer hoping to follow the St James Town trend. The rise of neighbourhood activism saved the Don Vale neighbourhood from “renewal” and the properties were held as modestly priced rental accommodation into the 1980s. When a small consortium of business people bought the properties in 1980, the tenants realized that their homes were heading for luxury conversion. A tenants’ association was formed and a battle plan developed to save as much affordable rental accommodation as possible. When the dust settled nearly two years later, the tenants had achieved a significant victory – Hampton Mansions had been purchased through the CMHC co-operative housing program. The name “Three Streets” was chosen in recognition of the original scope of the tenants’ ambitious campaign.

Hampton Mansions had been constructed in stages as three separate, three-storey buildings. When it became Three Streets, extensive renovation was carried out, with attention paid to restoring and preserving the historic elements of the building. The exterior yellow brick was carefully cleaned; the original woodwork in the hallways and staircases was painstakingly refinished; unit rewiring was accomplished with minimal damage to existing plaster; replacement iron work was designed to retain the Hampton Mansions decorative elements. One of the most exciting improvements has been the creation of a “secret garden” in the large interior courtyard. The members also added an ample roof deck that has stunning views of Toronto in all directions.

EJR

Today, Three Streets houses individuals and families at both market and subsidized rents. Through an agreement with the AIDS Committee of Toronto, one subsidized unit is reserved for a member who is HIV positive.

Cynthia Wilkey

City Park Apartments: 484 Church Street

Architect, Peter Caspari

Completed 1954

Village Green: 40 and 50 Alexander Street,

55 Maitland Street

Architect, John Daniels

Completed 1967

Two years after the 1952 completion of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseilles, High Modern residential architecture arrived in Toronto in the form of the City Park Apartments at 484 Church Street, just north of Maple Leaf Gardens. This, the first post-war apartment complex in Toronto, replaced the Victorian houses on its site with three 14-storey slab blocks containing 774 rental apartments.

“Espace, soleil, verdure” is provided for all residents, thanks to the east-west orientation of apartment units and generous spacing between buildings. Apartments are large, balconies private, and waiting lists are long. Following conversion to a non-profit housing co-operative in the early 1990s, City Park underwent renovations, including the application of vertical metal cladding on the north and south end walls of each block.

Thirteen years after City Park was built, the 700-rental-unit Village Green project was constructed across the street to the north. The three buildings – two 19-storey slabs (with two-storey penthouse units on top) and a cylindrical 28-storey point tower – are clad in white and blue glazed brick. Village Green provides lots of espace and verdure, but north-facing units lose out on soleil.

EJR

Both City Park and Village Green are examples of high-rise, high-density site planning at its best. An interesting comparison can be made with the two most recent developments in the immediate vicinity. The Alexus, at the northwest corner of Church and Alexander, is a condominium apartment building built to the property line that steps up from one to eleven storeys. It has a false front on Church Street (the cornice line of which unfortunately doesn’t match its older neighbour to the north). At 42–52 Maitland Street an infill development of 20 condominium townhouse units is packed so tightly on its site that rear windows are almost non-existent due to building-code restrictions. The high density of these and many other residential buildings in the area supports the busy Church Street commercial district, a neighbourhood shopping area, and GHQ for Greater Toronto’s gay community.

Douglas Young

108 Mutual Street

Current architect, Paul Northgrave

Completed 1910

Altered 1916, 1930, 2000

In 1910 Robert Simpson Co Ltd constructed on the southwest corner of this site a five-storey, reinforced concrete and steel structure, which was used for wagon storage and as a harness shop. In 1916 an 11-storey mail-order building and warehouse was added at the south end of Mutual Street, designed by Max Dunning and Burke, Horwood and White. The final construction phase of 1930 took place at the north and west sides of the city block. The design of the west facade is a fine example of multi-storey warehouse design. Over 12,000 people worked in this huge industrial building at one time.

In 1977 construction began on a new; mixed-use development (residential, retail, and commercial), after interior elements of the original building had been removed, except for concrete columns and floors. The Merchandise Building now consists of 504 loft residential units, 529 above-grade car parking spaces, 246 bicycle spaces, 4 loading bays, a 30,000-square-foot food store, and 35,300 square feet of retail and office space. The exterior masonry and concrete work has been refurbished, a new roof constructed, and double-glazed windows added to the building exterior. Two large six-storey openings have been cut into the building to bring fresh air and light into the building.

The residential lofts are accessed by shuttle elevators from grade. Parking is on the second and third floors. On the fourth floor there is a lobby and recreation area consisting of a fitness club, basketball court, steam and sauna facilities, concierge station, two guest hotel suites, and a large area for social gatherings.

The loft apartments are divided into three condominium communities, each having its own elevators, stairs, and mechanical and electrical systems. The apartments have 12-foot ceilings and large expanses of glass. Many of the apartments feature in their design the massive (48 inch diameter) interior concrete structural columns.

The three condominium communities share a rooftop “sky garden” with prairie meadow flowerbeds and a wetland garden. A new twelfth floor has been added to make space for an indoor pool, party room, dining facilities, and an outside dipping pool.

The total redesign and regeneration of this 1,070,000-square-foot complex is believed to be the largest of its kind in North America.

Paul Northgrave

241–285 Sherbourne Street

Completed 1976

Architects, A. J. Diamond and Barton Myers

Sherbourne Lanes stands out as a defining example of the impact of Toronto’s reform movement on the city’s architecture. The project represents an innovative way of providing high density housing in downtown Toronto. Following an era when most development involved the demolition of substantial tracts of the city’s traditional Victorian fabric to make way for apartment towers, this scheme proved that a high density residential project could be carefully inserted without disrupting the scale, material qualities, and urban virtues of the existing fabric. A city block of substantial Victorian homes, originally slated for demolition to make way for two 28-storey towers, was saved when Diamond and Myers produced a scheme that provided as many units as the two towers and maintained most of the existing houses. These were renovated to accommodate multiple units, and a six-storey apartment block was discreetly inserted at the rear of the houses’ original deep lots, preserving Sherbourne Street’s historic character. This was the first project by the City’s new non-profit housing company, CityHome, and it represented an important watershed in the City’s approach to urban renewal. Sherbourne Lanes received a Heritage Canada National Honour Award, a City of Toronto Non-Profit Housing Corporation Award, and an Ontario Association of Architects Award of Excellence.

CPD/CT

Marco Polo

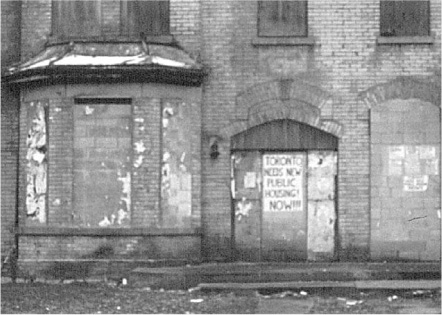

The intersection of Sherbourne and Dundas could be called the epicentre of the homeless disaster and housing crisis in Toronto. Long known for its extremes of poverty, human conditions in the area of Sherbourne and Dundas are worsening.

Many things remain unchanged since I first “cut my teeth” as a street nurse in All Saints Church 13 years ago. Buildings are still boarded up, people wander the streets, and most of the social services are in their original locations. Yet, a closer look uncovers a real tragedy. Social service agencies report seeing double the number of people since the provincial government cut welfare payments, and health workers report two to four homeless deaths a week in the city. They also know this is a severe underestimation of the death count.

The Sherbourne and Dundas intersection is an essential part of what we call the Disaster Tour that we give to community leaders, politicians, and members of the media to show the extent of suffering from Toronto’s housing crisis. First on the tour is All Saints, the magnificent Anglican Church at the Four Corners, which sports a bright new, blue sign listing the services inside: Street Health; a clothing store; the Open Door Drop-In; the Friendship Centre; and church service on Sunday at 11 am. Inside, in the Open Door, Doreen’s 50-cent egg sandwiches are still my favourite in town. People that are homeless can seek daytime shelter in both the Friendship Centre and the Open Door. Today, I see still-homeless people I knew 13 years ago and many new faces too. Although people are now allowed to sleep on the pews, many are sleep deprived from nights in crowded emergency shelters or sleeping outside. In one neighbourhood shelter, for example, close to 120 people sleep side by side on a concrete floor. No cots, sometimes not even enough blankets.

Across the street from All Saints, bold signs scream “ROOM FOR RENT.” These rooming houses are in an extreme state of disrepair, yet the need for housing is so desperate now that the landlord often puts two people in single, unfurnished rooms and charges each $320.

Down the street at Sherbourne and Queen there is an emergency shelter for men. North of All Saints, yellow brick houses remain boarded up, but sport a sign “Toronto needs new Public Housing Now.” Next to the boarded-up housing, there is a “rest home” that offers minimal rest, minimal health services, but a bed. The cost is high.

At Allan Gardens there are visible changes from 13 years ago. New lighting and other design changes discourage public sleeping or loitering with limited success. Allan Gardens is now colloquially known as the “Safe Park” after the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty’s attempt to create a safe place where homeless people could sleep. Students from the University of Toronto continue to sleep there every Friday night in a public appeal for solidarity with homeless people.

Michael McClelland

Across the street women and children sleep in a permanent shelter. The majority of homeless women and children, however, have been relocated to emergency shelters in the former city of Scarborough. The count for children there is 1,000.

Juxtaposed with the hotel and condominiums sprouting up on Jarvis and Dundas streets, the Sherbourne and Dundas area has had no new social housing for 13 years. It’s time to bring our people back into a home.

Cathy Crowe

Overnight shelters in Toronto provide temporary accommodation for more than 65,000 people annually. That’s almost double the number from 10 years ago. Children and families recorded the biggest increase. Almost 6,000 children are forced to live in homeless shelters each year. Some hostels are managed by the City of Toronto. Others are operated by private charities and receive government funding. Most provide dormitory-style accommodation – rows of bunk beds. Some families stay in suburban “welfare motels” where entire families are crowded into a single room. In the winter, some churches open their basements as part of “Out of the Cold” programs. Homeless people sleep on mats on the floor. The city’s homelessness disaster means that on many nights of the year Toronto’s homeless shelters are entirely full or at over capacity.

Michael Shapcott

319 Dundas Street East

Architects, Howard Walker

and Howard Chapman

Completed 1988

All Saints Church is the subject of the book My Parish is Revolting [General Publishing Co. Ltd., 1974]. The book chronicles the transformation, under the supervision of Father Norman Ellis, of this Anglican parish church in the urban core, from a failing congregation in the 1960s and 1970s as more affluent members left for suburbia, to a revitalized Centre for the low-income people that were left behind. The revival of the church’s presence in the urban core continued into the 1980s under Father Brad Lennon’s leadership. As the working-class neighbourhood was re-populated and renovated by affluent “white-painters,” the issue switched to preserving housing for the Centre’s low-income patrons who were threatened with displacement.

The Church’s Board rose to the challenge. It engaged the groups using the Centre to plan for the whole site. The need for housing was on everyone’s agenda. The Board convinced the Anglican Diocese of Toronto to apply to re-zone the land for housing, and to contribute the land to a project to build community space, offices for programs, and housing. The housing was financed with a provincial nonprofit program.

EJR

The units were small but all self-contained, different from the rooming-house-based models elsewhere. Prospective tenants were involved in design meetings, and continued on as management committee members, cleaners, and repair workers.

The entrance in between the Church and the old parish house to the east (where programs are held), is obviously newer construction, but evokes the Church and parish house architecture. The housing has its own entrance, which serves as an unobtrusive backdrop to the historic church buildings, but is physically linked to the buildings on either side. The complex of buildings preserves the presence of the low-income community that has been based in the neighbourhood for over 100 years. The old and the new, the drop-ins and permanent housing, and the government, secular agencies, and the Anglican Church in partnership with the low-income community, make it a fascinating island of hope in the urban core.

Bill Bosworth

119 Sherbourne Street

Current architects, Siamak Hariri,

Taylor Hariri Pontarini Architects

Landscape Architects: MBTW Group

Completed 1998

Robertson House is a Metro Toronto Community Services temporary shelter for women and their children. Two connected historic houses on Sherbourne Street were renovated and a new L-shaped addition added. The facility is organized around a new central courtyard for social gatherings and children’s play. The building attempts to avoid the “special housing” label by blending in with the scale of its urban surroundings. The image of the Robertson House addition draws on the metaphor of a single house, reinforcing the notion of a safe place of collective and individual living, which is both supportive and nurturing. The design attempts to be sensitive and understated, respecting the desires and needs of the users.

The three principal programmatic elements – the child-care facility, dining area, and residents’ lounge area – open directly onto the landscaped courtyard, which has a small secluded garden at the west end. The presence of children is celebrated by a circular story-telling room, the indoor play area, and the separate youth activity room. Also on the ground floor are connected prayer, study, and counseling areas. The lobby, which is staffed by a receptionist gate-keeper is designed to accommodate the flow of residents, visitors, and baby carriages, and to provide a feeling of security from the street. Ground floor circulation occurs along the courtyard perimeter and incorporates spaces for casual conversation, repose, and encounter.

The bedrooms, all on the second floor, are modest and intimate in scale. Each bedroom contains a dormer window and window seat, providing a private, quiet outlook for mother and child.

Siamak Hariri

John Ross Robertson, 1841-1918

Publisher and philanthropist, John Ross Robertson lived in this house, 1881-1918. He was born in Toronto and while at Upper Canada College he started The College Times, the first school newspaper in Canada. He became city editor of The Globe in 1865 and the following year with James B. Cook established The Daily Telegraph published in 1872. Four years later Robertson founded The Evening Telegram, which quickly became one of Toronto’s leading newspapers. Financial success enabled him to make substantial contributions to the building and operation of the Hospital for Sick Children and to gratify his life-long interest in history. He assembled an invaluable historical and pictorial collection and published some notable works such as “Landmarks of Toronto” and the “History of Freemasonry in Canada.”

Plaque text courtesy of the Ontario Heritage Foundation

• Taylor Hariri Pontarini

Bounded by Gerrard, Parliament,

Shuter and River streets

Completed 1947–59

Regent Park was Canada’s first, and remains Canada’s largest, public housing project. It was built in two phases between 1947 and 1959. The project replaced a neighbourhood that was similar to the one that remains immediately to the north, however, unlike the adjacent, now gentrified, “Cabbagetown,” the Regent Park neighbourhood had been declared a slum. Following the analysis of “environmental determinism” common at the time, the poor physical conditions of the neighbourhood were seen as the root of the social problems experienced by the residents. The urban renewal of the area followed the edicts of modern architecture, setting buildings in park-like surroundings, segregating pedestrian and vehicular traffic, and providing an architecture that assumed a set of universal needs on the part of the tenants.

EJR

The problems that have emerged in the neighbourhood have followed patterns similar to those in other North American public-housing neighbourhoods. Residents identify personal safety as an issue, noting that police have trouble patrolling a neighbourhood with no through streets. And, informal surveillance is also difficult because of the ambiguity about who controls the various semi-public spaces in Regent Park.

Originally intended to re-house residents displaced in the demolition of the old neighbourhood, Regent Park was designed with a culturally homogeneous population in mind. In the late 1940s, Toronto accommodated largely European, English-speaking communities. This has changed dramatically and social service agencies report that area residents now speak more than 60 languages. Regent Park has become a primary immigrant reception area, and in the process, one of Canada’s most culturally diverse neighbourhoods.

Although it is common for outsiders to perceive Regent Park as an undesirable neighbourhood, the area includes many strong communities and dedicated residents who strive to improve the physical and social conditions, and to improve the neighbourhood’s image in the eyes of the broader public.

Completed in 1954, North Regent consists primarily of unadorned brick buildings in three-storey “dumbbell” and six-storey “dog-bone” configurations. Designed by architect J.E. Hoare, the designs mirrored other North American public-housing projects of the period. Most of the 1,200 apartments are designed for households with children, including a large proportion of five-bedroom units. Although all the through streets were closed, their pattern is still discernible and the buildings roughly address the old alignments. Pedestrianized Oak Street, along with central ball diamonds and swimming pool, constitute the main social spaces for the neighbourhood.

There is little connection between the units and the common exterior spaces. Residents and social service agencies have been addressing some of the safety issues associated with this problem by initiating popular community garden projects in some of the more problematic areas.

In the year 2000, the future of the neighbourhood is uncertain as the Conservative provincial government has “downloaded” responsibility for public housing to municipalities, although most cities cannot support such capital-intensive projects on the property tax base. Through the 1990s, there were a number of proposals to rebuild parts of neighbourhood, including options for private initiatives that would retain the same number of rent-geared-to-income apartments while introducing a mix of household incomes.

The completion of South Regent in 1959 was accompanied by great praise from the architectural community. The neighbourhood is dominated by five towers designed by Peter Dickinson of Page and Steele Architects and townhouses designed by J.E. Hoare. The project won the Massey Medal for Architecture and was cited for its innovation. The 14-storey buildings, which are oriented to the points of the compass rather than the street grid, define the major public space, Saints’ Square. The buildings themselves have a “skip-stop” elevator system that allows units to have two aspects and through-ventilation. Like North Regent, most of the units, even in the towers, were designed for families with children.

The 1959 Canadian Architect review of the project comments on the tower facades: “Envisaged as patterned walls … their vibrant pattern of glass and brick firmly controlled by the grid of the structure. The central recession produces an upward swing of the two side wings which, where the escape balconies punctuate the facade, has a vivacity that fills the court below with the joy of rhythm.” Residents, especially those with children, find the buildings problematic, however, and many prefer to live in the more banal buildings of North Regent.

Richard Milgrom

2–52 Blevins Terrace and

1–73 Belshaw Place

Architects, Peter Dickinson

with Page and Steele

Completed 1958

As the Toronto slums were being bulldozed in the 1950s, the City entered into a controversial period of public housing and modern planning. Peter Dickinson’s maisonette towers, located just south of Shuter, on Blevins and Belshaw, formed part of the second phase of the Regent Park redevelopment which was well under way by 1955. Regent Park was seen as a community that would be protected from the old, unredeeming slums of nearby Cabbagetown and, to signify a break with this past, Dickinson based his design on modernist planning set forth by Le Corbusier and others. Dickinson’s towers for Regent Park South were executed while he was chief design architect with Page and Steele in Toronto.

The project is comprised of five 14-storey apartment towers sited around a central park known as Saints’ Square. The chief planner for the project, Ian Maclennan, abandoned through streets in favour of dead-end streets. Walking around the site today, the towers seem to be sited randomly with no relationship to Dundas or Shuter Street, or the edges of Saints’ Square. One does notice, however, that they are aligned carefully with the path of the sun, although at ground level, the pedestrian is barely aware of this fact.

Dickinson won national recognition for these towers when he received the prestigious Massey Silver Medal in 1958. He was proud of the open spaces created around the towers. On paper, the spaces looked attractive, but in reality, they were unadorned and empty of life. The inconvenience of poor shopping facilities and poor taxi, ambulance, and truck delivery access further isolated these towers and their communities, despite the proximity to a major thoroughfare. At Belshaw Place, for example, three or four token services are meant to satisfy several towers. Next to these insufficient services, Dickinson designed a heroic glass curtain wall exposing the mechanical plant on the ground floor.

Influenced by Le Corbusier, the interior design of the towers was innovative for its use of hallways on every other floor, allowing apartments to be built on two floors, with an internal stair connection. Le Corbusier first used this concept in the Unité d’habitation in Marseilles. The large apartments had at least two bedrooms that would work well to accommodate the population boom in post-war Canada. One curious design feature is the small balconies that give exterior access to adjoining units. In the event of a fire, one exits to the common balcony, then through their neighbour’s apartment. In case the neighbour was away or the door locked, Dickinson designed a glass box to house a hammer that could be used to break into the neighbour’s apartment, so an escape could be made.

Despite faults, Dickinson’s maisonette towers are seminal buildings in the history of public housing in Toronto.

Ian Chodikoff

EJR

Bounded by Parliament, Shuter,

River and Queen streets

Rehabilitated 1971, 1973, 1978

In the first years of the Depression, the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, Herbert Bruce, gave a stirring speech about poverty and grim housing conditions in Toronto. He urged that most central Toronto neighbourhoods be demolished to make way for new housing. After the Second World War there was a strong push to fulfill Bruce’s dream.

Neighbourhood demolition and reconstruction was called “urban renewal” and it had an active life in downtown Toronto from the late 1940s to the late 1960s. At that point residents in the Trefann Court area raised such political heat that the urban renewal strategy was halted in Toronto and in other Canadian cities and new solutions for regeneration were found.

The Trefann Court area is bounded by Queen, Parliament, Shuter and River streets. The City proposed to demolish almost all of the residential and commercial structures in the area; to build public housing in the westerly portion of the site, complimenting the Regent Park urban renewal area immediately to the north; and to permit industrial buildings on the east of the site.

With the help of community workers, the residents urged the City that their homes not be expropriated, that they be allowed to have significant involvement in replanning their community, and that an alternative to public housing be found. By 1971 the residents had made significant changes in the way the City looked at the Trefann neighbourhood and other downtown communities.

• Sewell, The Shape of the City

The following changes were significant:

• A planner was hired by the City to work from a neighbourhood office directly with residents. This was the first example in Toronto of citizen participation in planning, a policy quickly adopted by City Council for all neighbourhoods.

• The residents and the planner agreed that most of the existing community should be protected, rather than demolished, and that new construction should strengthen, rather than weaken, the existing community. This was the first example of the policy to preserve neighbourhoods.

• An alternative was found to public housing (where every household had a low income and paid 25 per cent of income in rent). In Trefann Court, a small housing project, of about 30 units, provided a mix of home ownership, market rental, and subsidized rental. This approach of mixing tenures and incomes was quickly repeated throughout Toronto, most notably in the St Lawrence community.

• Trefann residents convinced the provincial government to enact a new Expropriation Law that included the principle “home for a home.” The new law required an expropriating authority to pay full replacement value, rather than simple market value that reflected depressed prices because of urban renewal designation. The difference in cost to the expropriating body has been so significant that since this legislation was passed in the early 1970s there have been very few expropriations in Ontario.

The Trefann community barely stands out from other downtown neighbourhoods – which is one of its successes. However, one can find the innovative mixed-tenure, non-profit, housing project on the west side of Trefann Street (the first street east of Parliament); new City of Toronto Non-Profit Housing Corporation units on Sackville Street; and through the rest of the area, a mix of new and old housing, private and non-profit, some buildings more attractive than others. On Sumach Street, between Queen and Shuter, there are the remnants of the only large, new industrial building in the area that the City subsidized as a prelude to urban renewal, but it has now been converted to condominiums.

EJR

(For further information, see John Sewell, The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning. University of Toronto Press, 1993.)

John Sewell.

397 Shuter Street

Architect, Philip Goldsmith,

Quadrangle Architects

Completed 1984

On the south side of Shuter Street, west of Parliament there are two matching rowhouse buildings, half a block apart, one perpendicular and one parallel to the street. This is the Toronto Women’s Housing Co-operative (TWHC), the second of three women’s non-profit co-operatives built in Toronto. The Constance Hamilton Housing Co-operative, located in the Frankel-Lambert neighbourhood, opened in 1982, and the OWN (Older Women’s Network) Housing Co-operative, located south of St Lawrence Market, opened in 1997.

Incorporated in 1984, TWHC is also called the Beguinage by founding resident-members who were inspired by a historic model of women’s communities – medieval European beguinages were small urban communities of unmarried women who lived apart from conventional families and at arm’s length from male-dominated church control.

EJR

The stacked town-house design of TWHC contains 28 units, with 13 one-bedroom units, 12 two-bedroom units, and 3 three-bedroom units. Each unit has a large private balcony or a fenced yard at ground level. Townhouse units have direct access to the street, and one-bedroom units share small vestibules. The project includes a co-ordinator’s office, a workshop or storage room, and a laundry room. Due to design constraints imposed by the government funding program and because the TWHC was a turnkey development, there is little in the building design or layout to distinguish women’s ideas and preferences, other than the communal courtyards at the back. Though not articulated in its physical form, the TWHC is distinctive in its creation of a unique women’s space and supportive community.

The TWHC is an example of how women’s groups across Canada have used existing social housing programs to develop non-profit housing for women. The self-management model of housing co-operatives has provided opportunities for residents to develop their management and leadership skills as well as to maintain control of their residential environment and provide mutual support.

Sylvia Novac

Architect, Paul Reuber

Expected completion, 2000

The row house at 63 Seaton Street was originally situated in the middle of a block of attached Victorian terrace houses. In 1954, Shuter Street, which at the time ended at Sherbourne Street to the west, was extended eastward across Seaton to Parliament Street. As a result, the row houses south of 63 Seaton were demolished and the south party wall of 63 was suddenly exposed to Shuter. Although the street frontage of the wedge-shaped side yard formed to the south of 63 Seaton is only 4 centimetres, the rear yard’s dimension of 7.8 metres was regarded by the owner as decidedly more tempting…

In 1989, a new three-storey infill house was designed for the wedge-shaped side yard. The design for the new free-hold house accommodated the specific living requirements of the owner of 63 Seaton – a doctor with an extensive art collection. The south end wall of 63 Seaton has been restored to its former party-wall status. Owner and architect wanted the new building to cauterize a part of the city block that had been previously wounded by the rather barbarian insertion of a new roadway.

• Paul Reuber

Although this house is shaped like a piece of pie, City Hall approval to build it was no piece of cake. Neither the neighbours, nor the Planning Department shared the enthusiasm of the owner and architect. Fortunately, the Ontario Municipal Board approved its construction after a time-consuming and costly appeal. Then the capriciousness of the housing market and the owner’s purchase of a new home elsewhere nearly caused the project to be shelved permanently; however, it was extensively redesigned and built as a speculative venture eleven years after its initial conception.

The front of the house may be only an entry door wide, but the principal rooms at the rear are more spacious and airy than those in its Victorian neighbours.

Paul Reuber

Bounded by Sherbourne, Shuter,

Parliament and Queen streets

Architects, Somerville McMurrich &

Oxley, with Gibson & Pokorny,

and Wilson & Newton

Completed 1961

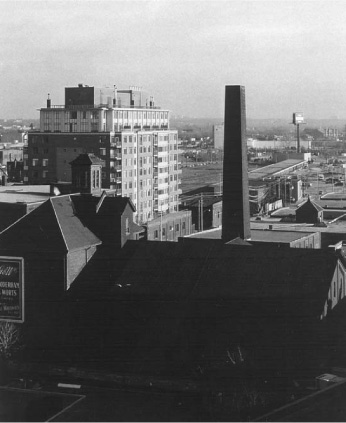

In the early 1960s, the City razed several blocks of 19th century Victorian housing and constructed three 16-storey, Y-shaped, public housing towers known as Moss Park Apartments. In the 1970s, a fourth tower was added. Under-utilized parking lots partially surround these towers at grade. To the south a sizable park is well used by tenants and the local community.

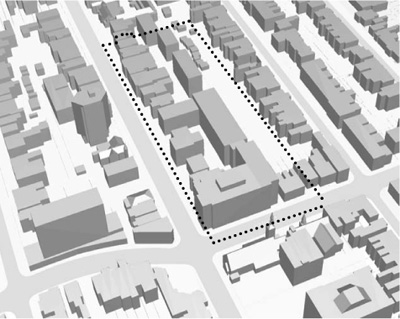

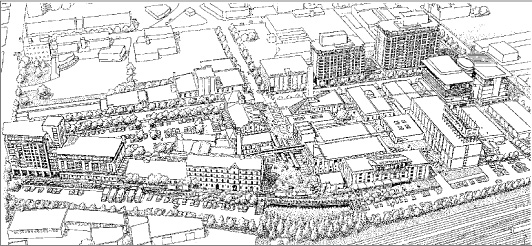

In 1991, the Province of Ontario’s Ministry of Housing funded a community-consulting process called the Moss Park Community Development Project. A working committee was formed that included building residents, the City, Homes First Society and the Supportive Housing Coalition of Toronto (both providers of non-profit housing), and the writer as the committee’s planning consultant. Two phases of work were identified: Phase I calls for the refurbishing of existing housing towers; Phase II proposes infilling the super-block’s parking lots with 220 new, affordable housing units, which would eventually pay for Phase I.

• Paul Reuber

The Urban Design Guidelines set out in Phase I have, in part, been executed by architect Ted Sievenpiper and include new lobbies and amenity spaces.

Phase II calls for a new system of public streets, lanes, and pedestrian stroll-ways to create eight new building sites. Different housing typologies were developed to respond to the particular size, shape, and location of each site, and include row houses, stacked row houses, several smaller apartment houses, and a larger courtyard apartment block. The plan sets a community/cultural centre in the park to serve the entire neighbourhood. It was proposed that families, currently living on the upper floors of the deteriorating towers, be given first choice to move into the new housing at grade. As older units became vacant, they were to be refurbished to house adults on marginal incomes.

The partial implementation of Phase I enjoys a somewhat peculiar relationship to the existing site plan due to the cancellation of Phase II, which remains a theoretical planning “vision.”

Paul Reuber

Bounded by Jarvis, Shuter,

Sherbourne and Queen streets

Built c. 1830; demolished

Moss Park, with its baseball diamonds and recreation centre, is perhaps hard to imagine as the estate grounds of one of Toronto’s early family dynasties – the family of William Allan (1772–1853). The park is notable for the following reasons: 1) Moss Park and, further north, Allan Gardens, are one of the few green reminders of the park lot system that subdivided early Toronto into its aristocratic parts; 2) These park lots, running from present-day Queen Street to Bloor Street and defined roughly by today’s north-south streets (in William Allan’s case, George Street to Sherbourne Street), defined the cartography by which Toronto housing lots would develop; 3) Moss Park is a reminder of the Allan family’s interest in promoting the civic virtues of landscaping and horticulture.

A handsome Greek Revival house set in a picturesque landscape, the northern reaches of the Moss Park estate were subdivided in 1850. Tree-lined Pembroke Street was built, and stately homes marched north. The Allans maintained their estate house in Moss Park for some time. Allan Gardens was donated in 1860 to the Toronto Horticultural Society by William Allan’s son, George (the future Mayor of the city), “for the enjoyment of all citizens.” It was meant to be surrounded by a Nash-like oval, divided with lots for villas, but this idea was never realized.

David Winterton

Architects, Tsow and Pollard

Completed 1984

The building at 90 Shuter Street is the Homes First Society’s first project to replace the low-rent housing and rooming house stock that was lost in the late 1970s real estate boom. Purpose-built, it has 17 “rooming houses,” i.e., 17 four- and five-bedroom apartments, two per floor in the 11-storey apartment building. The rooms are large. Drywalled concrete block walls provide sound and fire separation.

The design maximizes individual privacy. There are only four or five people per apartment and only nine people per floor. The small groups facilitate group interaction, decision making, and problem solving. Tenants have keys to stop the elevator only on their floor, to promote the sense that the apartment-front-door is the door-to-the-street.

The lounge in elevator lobbies on each floor is for interactions between the two apartment groups. The ground-floor common space (with kitchen), by the front door, is for “drop-in” relationships on the way in or out, parties, and programs. The second floor common room is for organized meetings, parties, and programs. The top-floor deck provides outdoor space away from “friends” on the street. A top-floor workshop space is available for hobbies and for community economic development. Offices on the ground floor are for staff and tenant management, and agency service delivery.

The partnership of community agencies, citizens, tenants, and staff at 90 Shuter represents a holistic, community-development approach. Tenants self-selected into the initial groups, in a unique organizing process that allowed them to develop expectations and group rules before occupancy. Community members from the Board sat on committees with tenants and staff to ensure due process, to help solve problems, and to consider evictions.

In the year 2000, in a mean-spirited political climate where “the bottom-line” rules, this holistic philosophy has a low standing in many people’s eyes. Yet, when you see a former “biker” chide an agency worker for marking up the paint on moving-day – “Hey!! This is my house!!” – the benefits of the approach are obvious.

Bill Bosworth

147 Queen Street East

Van Nostrand Di Castri Architects

Completed (renovations) 1990

The Queen and Jarvis building dates from the 1950s and sits on the site donated by the elder Hart Massey in the late 1800s. The building was constructed as a men’s hostel and senior men’s home, the vision of Reverend Wesley Hunnisett, who had housed transient working men in the St Lawrence Market during the Depression (the same man and his philosophy was behind Seaton House, the City hostel on George Street).

Fred Victor Mission has served low-income people for over one hundred years. It started as a mission of the “Methodist Cathedral” (now the Metropolitan United Church), it ran schools, penny savings banks, fuel cooperatives, and programs for families in the low-income neighbourhood to the north and east.

Before renovation by John van Nostrand, the building was an industrial-looking, dull-yellow brick, with aluminum windows, built to the lot lines on Queen and Jarvis streets. It was home to 120 men in the hostel each night, and 60 senior men in the home. The hostel residents were “permanent,” just on a rotation in and out for a few days, months, or years at a time.

The goal of the project was to replace the 180 “beds” on the site. The architect faced the challenges with creativity. Since setback requirements for new construction would have limited the potential of the site, the building had to be renovated. He inserted reverse-bays into the walls to bring light into the new multi-room units. The cladding lightened the impression of building mass despite the fact that the “wrong colour” was delivered in the midst of the building boom and could not be corrected.

The Fred Victor “Mission” became the “Centre” with computer training, support for economic development, a cafeteria, and many innovative programs to support the lives of the men and women in the housing, and those still on the streets, who see Fred Victor as their “home” if not their residence.

Bill Bosworth

Beginning in the 1960s and early 1970s new provincial policies encouraged the deinstitutionalization of people with mental illness, which resulted in an increased demand for affordable housing. At the same time, the supply of affordable housing stock in Toronto diminished because of gentrification in the downtown areas (especially of rooming houses), low rental vacancy rates, and, finally, high unemployment forced many people to seek cheaper housing. Thus, as early as the 1980s, Toronto began to experience a crisis relating to the lack of affordable housing.

Rooming and boarding houses form an essential component of the housing continuum since they provide low-cost housing at the very bottom of Toronto’s housing market. For many vulnerable people (often mentally ill and not receiving treatment) the only other choice is the street. Unlike self-contained housing, rooming and boarding houses have at least one shared facility: bathroom, kitchen, or living room. Rooming houses provide accommodation only; boarding homes provide meals and care services.

In 1974 Toronto City Council passed by-laws to require owners of non-owner-occupied rooming houses with five or more tenants to obtain licenses, submit to inspections by City officials, and meet standards for fire protection and maintenance. It has been argued that this regulation has been a major factor in the significant decline of the stock; however, decline was also fueled by gentrification and other forms of urban development in the mid-1970s. Rooming houses have been regulated since 1987 by the Tenant Protection Act. From 1986 to July 1999, licensed rooming house stock has declined from about 600 homes to 389 homes. Boarding home stock has always been more limited. Of the rooming houses currently licensed in the former City of Toronto, only 60 operate as boarding homes. Currently, rooming and boarding houses are only legal within the old boundaries of the City of Toronto and Etobicoke. Most are located in Parkdale and Cabbagetown, close to the community services that rooming and boarding house tenants rely on. Neighbourhood opposition will make it difficult for existing licensing to be extended to the other four former municipalities that were amalgamated to create the new “megacity” of Toronto.

Agencies working with the homeless see other pressures further reducing the boarding and rooming house stock. The province, for example, has removed its legislation protecting rental housing, opening the way for the conversion of rooming houses to single family housing, rental apartments, or condominiums. And the removal of rent controls has permitted rents to escalate. The typical monthly rent for a decent room in a rooming house in Toronto has gone from $425 to $500 over the last two years, well above what people on social incomes are able to pay. Changing municipal taxation policy may quadruple the taxes for larger rooming houses, thereby raising rents; and the evolution and enforcement of municipal standards for rooming and boarding houses may also raise owner’s costs. Some owners and operators are now reaching retirement age and are looking to sell their properties and/or the business.

Trends in the banking and insurance businesses are also increasing the costs of operating boarding and rooming homes. Trust companies, the usual mortgagor of the houses, are being absorbed by the major banks, who subsequently withdraw from this line of investment. Rooming house owners are forced to seek private or offshore investors for mortgage financing at significantly higher interest rates. Insurance companies are also scrutinizing the boarding home business, and charging higher premiums.

The housing market is becoming tighter. In the private sector it is easier to increase rents, forcing those who could afford previously to live in self-contained apartments to move into rooming or boarding homes. Landlords of rooming and boarding homes have become more selective in choosing their tenants, and current tenants are being forced out and into substandard housing or onto the street.

The City of Toronto must develop strategies to prevent the loss of valuable rooming and boarding house stock and to encourage new investors into the sector.

Alison Guyton

Rooming houses (sometimes called Single Room Occupancy units) provide affordable housing for low-income people. Since the 1970s, gentrification has led to the loss of tens of thousands of rooms, which have been replaced by high-priced “yuppie palaces.” The migration of young professionals into poor neighbourhoods has also led to demands for more aggressive policing against low-income and street people. A fire in December 1989 at the Rupert Hotel at Queen and Parliament streets, which left 10 residents dead, sparked an innovative pilot project. Co-ordinated by a community-based group, the Rupert pilot project used provincial and municipal funds to renovate more than 500 units of rundown rooming house stock. The project created successful models for collaboration between government and community, but new development stopped in 1993 when the provincial government refused to renew funding.

Michael Shapcott

393 King Street East

Architect, Dermot J. Sweeny

Completed 1988

The Derby, which stands at the southeast corner of Parliament and King, makes a handsome terminus for the King Street vista seen from the west. The project, initiated by Ron Thom’s Toronto office, was brought to a successful conclusion by Dermot Sweeny. Twenty-six innovative mezzanine lofts (long before “loft” became the ultimate marketing buzz-word it is today) and the commercial space at street level fit in well in this zone of (formerly) clandestine lofts and industrial buildings.

EJR

David Winterton

Northeast corner of King and

Parliament streets

It was 1978. A newly registered architect, with more ambition than cash flow, was looking to open a new office. The City of Toronto was, against enormous pressure, pursuing a policy of preserving industrially zoned land. The over-heated real estate market had created absurdly high rental and purchase costs for traditional housing.

At the corner of King and Parliament, a landlord combined with a small group of prospective tenants to create a loft community in a downtown warehouse building. It was one of a number of illegal lofts that were springing up on the shoulders of Toronto’s downtown, originated by people who were following the example of artists and others in New York, London and elsewhere around the world, and who were willing to take risks in return for unique opportunities.

The building at King and Parliament offered brick walls, mill construction wood floors, high ceilings, huge windows with great views, and total flexibility in layout. It also featured substandard heating, freight elevators that were an adventure with every use, and a virtually total disregard for fire safety codes. But for a new architectural practice, the $250 per month rent (and that was gross rent!) for 750 square feet of “funky” space was an offer one could not refuse. The space, at the northeast corner of the fourth floor, subdivided easily into living and working areas, and suited the needs of a fledgling practice. Working hours were flexible, and the area lent itself well to entertaining or business meetings, whether long solitary hours of drafting, groups pulling an all-nighter, dinner for two, or a working lunch.

It was presentable as a business address and met the desire for a downtown lifestyle, being within a few minutes walk of King and Yonge, the St Lawrence Market, restaurants, theatres, and the squash club. The daily experience of watching the downtown-bound traffic pour onto Richmond Street from the Don Valley Parkway as I dressed for the day reinforced the conviction that this was a viable alternative to the suburban/urban dichotomy that had become the norm in North America.