The Receiving of Envoys: George McDowell Comes to Town

When she’d left home to go to Sydney University, George McDowell had been the most promising young man in her district, although sometimes laughed at for his schemes. He’d gone on with the blind expectation that people should take him seriously, and as long as he paid his bills, she supposed they would take him seriously, and she presumed that George made money, although he never seemed to boast about it and did not live in a flashy way. Though she remembered that he always sought to be treated preferentially with expressions such as, ‘I know this is not the usual way things are done but I want you to do it for me as a favour’, or ‘I am going to ask you to do a rather difficult thing for me.’ Older men called him ‘Mr McDowell’, even when he was barely twenty-one. He had a rapid manner, reminding her, in recollection, of some of the earlier, jerky motion pictures.

While at university she had been his ‘agent and technical adviser’ in one of his schemes for marketing a water clarifier and had made, she recalled, about fifteen guineas out of it. He was the only man she had ever seen wear overalls over a suit and tie but it expressed him perfectly. He was always ready to muck in on a job but underneath it, he was always the manager.

Although he was a few years younger, she’d flirted with him at balls when she had been home on vacation. As a suitor, he had been a possibility, but she had other roads to travel. George was a man with big ideas in a small town, and she could not see herself back there, living on the coast with George.

The letter from George said he was coming to Geneva. To ‘inspect’ the League for himself.

She remembered that George, as a young man, had been the first person in their circle to go overseas. He had gone not to Europe, but to the States, where he believed the future lay. There’d been Scribner, an older man of no particular age, who’d earlier been to Oxford, or at least that was what people said, but if he had been to Oxford and gained a degree, what was he doing back in the town?

Scribner existed without a job, although he was always in the street first thing in the morning in collar and tie, involved in undertakings of a mysterious personal kind which seemed to fill his days, and from time to time he worked with George on schemes, writing brochures, cranking handles, driving George about in George’s Studebaker tourer, both of them dressed in white dust jackets, goggles and suits.

As much as she had affectionate memories of George and of those days, Edith really didn’t want George McDowell in Geneva and around in her life now. She wasn’t the flirtatious girl from the town balls any more, doing the hokey pokey and the progressive barn dance. She certainly was not ‘Edy’, as George had addressed her in the letter.

There was something unnerving about the idea of a visit from someone she had left behind. John had been different — he belonged half in her world anyhow. George’s visit would mean facing the self she’d left behind. The discarded self, even. Did the visiting person seek to find the person they’d known? Or did they hope to find a new person who’d surprise and dazzle them? Or did they fear meeting some formidable new person who would dismay them? Whatever, it was an unwanted reunion with no definable purpose.

Typically, he talked in his letter of her helping him to make ‘the best use of his time in Geneva’. George led a relentless life.

George would want to meet Sir Eric. Oh, she saw it now. George believed in ‘going straight to the top’. Just when she’d begun to be noticed by Sir Eric and had the very special bond with him, along came George to muddle it. Admittedly, she hadn’t been back in that office since the crisis about Germany and the shaving of Sir Eric. It was as if that special morning were something holding them at arm’s length in their work, that Sir Eric did not dare allow her to be too close again.

She couldn’t arrange for George to meet Sir Eric, anyhow, but deep in her heart she knew that, by one means or another, George would get to see Sir Eric. As long as he didn’t drag her into it. The more she thought about it, the better it was that he do it himself, and she would beg him not to mention their connection back in Australia. At all. In any way.

It then crossed her mind that George might propose to her if he wasn’t yet married to Thelma, the belle of most of the balls, who came from one of the older families. One of her mother’s letters had mentioned Thelma.

It wasn’t that Australia was not a ‘real’ place, full of real people doing real things, finding happiness, making families, practising the arts of friendship, practising the arts of politics, and practising, albeit in a youthful way, the arts and scholarship — doing all the things she knew mattered in life. It was that she needed now in her life to put herself in a position which made her productively nervous. Even if it was a bit uncomfortable at times. She had to be where she didn’t know quite what was happening next, to be living precipitously. She wanted to be in the presence of people who made her a little nervous. She wanted to be among objects, buildings and art works which made her mindful and sentient, which could cause her, now and then, to be in awe.

She wanted to feel that she was absorbing from her world, she wanted to feel as if these buildings and objects were entering her spirit. She knew that French culture, or at least Genevan French culture, would shape her, not into a French person, but into another sort of person.

There was a loss from living in Europe, she acknowledged. For instance, on the day she first visited Mont Blanc, she had lost the mythical ‘Alps’ of her childhood with all their fables and fantasy. They were no longer ‘the Alps’ in quite the way they’d been before when she had seen only photographic postcards or just heard the words ‘the Alps’. They were mountains now.

She had also lost mythical ‘Europe’. The mythical Europe of her childhood picture books and the many hearings of the word spoken so longingly and with such aching and worried significance by the adult world around her as a child. She lived in a real Europe now — and in some minor ways, regretfully. A Europe of visible and touchable places to walk, to ride, to shop, to eat and drink — and of dull and ugly places as well.

Still, sometimes on a mountain road driving around a bend to face a vista of farms and churches and fields she became breathless, or when driving through the dark, narrow, winding cobble-stoned streets of a village. The word Dubonnet on a sign above some tables and chairs could still thrill her.

She was willing to forgo such things as family and friends for now, to have placed herself where these European sensations might become part of her, because she felt at times that she might not be able to have her own family, could not yet see how that could be in her life. It was also true that she was not sure how much she was prepared to forfeit to be able to have these sensations of Europe and the work of the League. She prayed that what she was pursuing was more than just sensations. Or more, that they were consequential sensations. And, as time moved on, she was aware of the dire bargain she was making with her life, and with her womanhood.

Sir Eric wanted them to be representatives of their nations within the Secretariat, in the sense that they should be able to guide the League in its dealings with their own countries, although no one had officially asked her anything about Australia since she’d been at the League. Nothing whatsoever.

For good or for ill, she now lived in Geneva. The capital of intellectual life, as Flaubert said. Her life was assemblies, congresses, receptions, banquets, and she had a lover. That was her life and that was how she wanted her life for now. She did not see how a visit from George fitted in.

Would she introduce Ambrose to George? She groaned. Not likely.

She sat in her office and ashamedly cursed George McDowell away from Geneva and her life.

The curse did not work. George came. George paced about her office, examining the pneumatic tubes, the window-opening devices, holding the League notepaper to the light to look at the watermark, and standing on a chair to look at the electric light. She wished her office wasn’t so small, was more impressive for George to report on back home.

He glanced through the files on her desk.

‘Those files are confidential, George. Secrets of the nation states of the world.’

‘“Have no secrets”,’ he stated to no one in particular, but he respected the files, and closed them. He took the glass from over the water flask, and poured himself a drink. He appeared to ‘taste’ the water. He was cultivating his taste, he’d told her. He went to look at one of Mantoux’s jokes pinned to the wall.

‘It’s an office joke, George.’

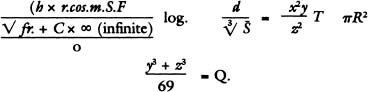

She was frightened that he’d take it seriously and write it down in his notebook. The joke was a ‘formula’ for disarmament.

PROBLEM: Find out on the basis of what principles it would be possible to establish the proportion of armaments to be attributed to each country, taking into consideration especially:

the number of inhabitants. … . . a

the resources of the country. … . . r

the geographical situation. … . . s

the length and the nature of the maritime communications. … . . cos. m

the density and the extent of the railways. . . F

the vulnerable frontiers and the vital centres near these same frontiers. … … . . fr

the time necessary (varying according to the different countries) to transform armaments on a peace footing to armaments on a war footing. … … C

the degree of international security, etc. … S

SOLUTION:

‘Has anyone tried it? It might work.’ He next looked at the Punch cartoon of the ‘League of Nations Hotel’ and laughed.

Edith saw it afresh after all this time and decided to take it down. It was something she no longer saw on her wall.

Turning back to her he said, ‘On this trip I’ve picked up five new ideas. I came from the United States to here. You know I’ve been to the United States twice now? Do I sound American? You can’t help picking up some of the American way of talking. I’m not going to England because England has nothing to teach Australia.’

That was typical of the breathtaking ideas that George came up with — to travel the world and to avoid England.

‘But I came here because Geneva’s more important than London. That’s one reason why I looked you up. I am admiring of you, Edy. You were the first internationalist from the south coast. Maybe the first from New South Wales.’

‘What about Scribner?’

‘Scribner?’ George chuckled. ‘Scribner. You know what he asked me to bring him back?’

She shook her head. ‘I’d imagine it would be a book or a musical score.’

‘Wrong. He wanted me to get him a honey spoon.’

She allowed herself to laugh. Suddenly it was nice to hear about Scribner, Doctor Teddy Trenbow and the others from her younger days. These people lived on in her life now only in dreams and recollections; they would never reappear in her life. Except for George. ‘A honey spoon!’

‘A wooden Alpine honey spoon. I’ll admit I’d never heard of such a thing. It exists, all right. It’s made of wood and doesn’t look like a spoon. It has this grooved end. You push the thing into the honey pot and twist it. It winds up the honey. You hold it over the bread and unwind the honey onto the bread. Scribner explained it to me. In fact, he made a drawing of it. I’ve got it back at the hotel.’

‘We’ll have a look for one.’ She was beginning to relax with George.

George said there could be a market for it, Australians being big honey-eaters. Then he said, ‘Scribner is not an internationalist or a citizen of the world.’ George stood at the window presumably thinking of Scribner and at the same time examining the geraniums in her window box.

He laughed. ‘I remember you lecturing me about gardens. You told me that gardens were nature in a prison.’

She had once said that. She smiled, flattered that he’d remembered something she’d said. ‘Yes, that is my little prison. Those are my Swiss geranium prisoners.’

George turned to her. ‘Seriously, you were the first from our district to know what it was all about. About being international.’

He waved his monogrammed leather-bound notebook at her. ‘I don’t mean inventions. I mean ideas in the realm of the philosophical.’

She leaned back in her chair and smiled at him with the protective superiority of an older sister indulging the enthusiasms of a younger brother.

‘An example: take this key.’ He went to the door and removed the key. ‘The teeth of this key might be the same as in other countries; the shank is the same; but in every country I have visited the finger-turning part is different. Why is that?’

‘I’ve really never thought about it, George.’

‘It has to do with different countries’ ideas of what looks good. Beauty.’

She’d never heard him talk of beauty.

‘I have another example not related to beauty. Back home when travelling I always carry a strong electric light bulb because the bulbs in hotels are too weak. But the world has foiled me. Each darned country has a different sort of socket and different voltage. I’ve turned it into a lesson. I will put that light bulb on my desk back home to remind me.’

He didn’t sound at all like an American but he wanted to, so she let him think he did. He had pep and she liked that.

‘Do you know what that badge is?’ He leaned over to her and held his lapel towards her.

‘No, George, I don’t.’

‘That, Edith, is the badge of Rotary.’

He explained that Rotary was a world organisation of businessmen. Not just any businessmen. An organisation of the most motivated of men, those with the esteem of their fellow businessmen. Those businessmen with respect for life. Membership was, he said, by invitation.

‘It is not the differences in locks and key and taps and switches that worries me. What gets me down, from time to time, is that people love their differences too much,’ he said ruefully. ‘And, believe it or not, I think the world could learn something from Australia.’

‘One day we will all be one,’ she said.

George burst into a song from the musical Belle of New York, ‘“Of course, you could never be like us, But be as like us as you’re able to be”.’

She laughed. George seemed to have attained a much better balance between the serious and playful parts of his nature than she remembered.

‘What do you think the world has to learn from Australia, George?’

He thought before he spoke. ‘No bombast. No showy politics.’

She said jokingly that she’d learned new approaches to tendering since coming to the League. She told George of her advice to the Directors’ meetings. ‘My friend Florence said that I could’ve furnished my rooms by taking gifts from the tendering companies.’

‘Don’t ever do that, Edy,’ George said with concern. ‘It’s better to be hard up than to have to live your life feeling bad about yourself.’ He leaned over to her across her desk. ‘Bribery is death to a good country.’ Then he grinned. ‘If you’re short of a chair, I think I could make a contribution.’

‘No, George, I’m not short of a chair — but thanks. And I don’t take bribes.’

‘I never thought for one minute that a girl from the south coast ever would.’

She winced as she recalled the gift of a pistol in her first days at the League.

In the Jardin Anglais, he had coffee and she a glass of wine. George still didn’t drink alcohol, although he did taste her wine. George tasted everything. Apart from having a passion for wine, she realised with a frivolous, faint embarrassment, that she was also having the glass of rosé to show George that she was a woman of the world now, who could drink alcohol and who knew her wines.

‘For the French, George, wine is food.’

‘For a young man like myself it’s a mighty powerful food,’ was all he said.

He said he was impressed with her French but that he believed that all people understood one language. Did she know what language that was?

She told him that Briand had said that he and Herr Stresemann were now speaking a new language — the language of Europe.

‘I don’t know about the language of Europe. The one language I do know about that all peoples understand is the language of Usefulness,’ George said, smiling. ‘I can get across to people as long as they know I am a man of use to them. What is my letter of introduction?’

She shook her head.

He held out his hand, ‘My handshake is my letter of introduction.’

His face showed that he was about to change the subject, and that the subject was important, delicate. ‘Edy — about your speaking of French.’

‘“Edith”,’ she corrected. ‘Yes, George?’

He seemed to leave what he had been about to say, and now seemed to ponder her shift from her girlhood name to her full legal name. He seemed to come to a private conclusion about that, and then returned to what he had been about to say. ‘“Edith” — sorry. I want to say something to you straight from the shoulder.’

‘Go ahead, George.’ She took up her glass of rosé as if it would shield her, a chalice of magic fluid. ‘You were always one for straight talking, George.’

‘I want to say that I find that you sound different. Very different.’

‘I sound different?’

‘When you speak English, you don’t sound like the Edy I know.’ He looked her straight in the eye, his jaw firm, then remembered. ‘Sorry, “Edith”.’

She coloured because she knew what he was talking about: her intonation had perhaps changed. Sometimes she wondered whether hidden parts of herself came to express themselves through her use of another language, especially when that language encouraged, well, certain mores, traits and peculiarities. She thought briefly of her carnal behaviour with Jerome, and with Ambrose, whether that had to do with her being impelled to speak French and to live a French way of life. The ‘French’ coming out in her? She was sure she ate differently, with more attention to her food and with more pleasure — that came from the French. What of the sinister, nastier traits which might sneak out through the speaking of another language? What if she were speaking one of the less cultivated languages — what would come out then?

Then he said, ‘The Japanese believe that when you learn another language you lose part of your Japanese self. They think it’s a bad thing.’

Where did George pick that up? ‘We should all have another self or part of our self perhaps which isn’t tied to one nationality,’ she said.

He said that he thought that learning another language might be a way of disguising oneself.

‘It’s perhaps a way of slipping across the border,’ she said.

‘Do you know what I think about learning another language?’

‘No, George.’

‘I think it means having to learn two words for the same thing.’

‘It’s a key to the door of another culture,’ she said. ‘You get let into another people’s secrets.’ She hoped he didn’t ask her to give him an example.

‘Maybe one day I will learn. I want to be a cultivated man, Edy, but it’ll just have to wait. I’m in too much of a hurry.’ He showed regret and then pulled himself into another mood. ‘I see why you don’t want to be called Edy. I know about wanting to get away from childhood.’

‘You were called Georgie.’

‘And Pudden. And Pie. And King.’ He smiled quickly. ‘Rather liked King as a name. Billie Fowler still calls me Pudden. I’ve asked him to stop. He won’t.’

She was still holding herself defensively, but knew she’d better face it somehow. It had to do with mouthing French sounds, day in and day out. She had let her voice change and maybe even pushed it in that direction because she was glad of a new voice.

‘I’m an internationalist now,’ she laughed. ‘I had to change, George. What would be the point of being an internationalist and not changing?’

George didn’t laugh. ‘No, Edy, it’s more than that. I see myself as a Rotarian and a Rotarian is a citizen of the world. I don’t speak differently. Except for the American style of speech which is because I was there for a few weeks and I admire them. I picked up American because I wanted to be like them a little. That’s different. Americans have a way of speaking to convince themselves of what they’ve just said. They stimulate themselves with themselves. In business, that’s good.’

‘In politics, that’s bad.’

‘In politics, that’s bad, I agree. With me, it’s mostly playing around. I fear for Edith, the person.’ He reached out to hold her hand. ‘I am talking, Edith, about you, the Australian.’

She was shaken slightly because he made it sound grave. She was facing the representative of all that she’d left back home. She didn’t think she’d changed as much as that. Still, she had not been back to Australia to hear herself — if you could ever hear yourself. George made it sound like a treason, punishable by ominous penalty.

‘Have you been homesick?’ he asked.

‘Not really.’

‘I see.’

Was the opposite to homesickness — desertion, disaffection?

‘May I talk to you about your card?’ From his wallet he took the business card she’d given him when he’d first arrived. He placed it on the table squarely between them. ‘I want to say something about your business card.’ He studied it while finding his words.

‘I think using an initial in your name is a natty manoeuvre. Very American. I might do it one day myself but I’d be laughed at back home. Not that being laughed at has ever stopped me. When my firm’s a bit bigger, I might add a letter to my name. To stop me being confused with my father.’

‘I didn’t see it as American. I saw it as making my name memorable.’

‘Precisely. Good move.’

‘What else?’ She swigged her glass of rosé.

‘The card gave me my first clue.’

‘To what?’

‘To your metamorphosis. To your personality predicament.’

‘George — I may’ve picked up an accent and I may’ve played about with my name but I don’t see that I have a predicament.’

‘I’m not so sure about that.’

She became aware that her defensiveness had within it a suppressed real fear, which was wriggling up from her soul, a fear of being exposed as a cheat. ‘We all have to grow up.’

‘Definitely. I don’t say that. What I say is that we have to keep on growing “upward” and I say that it’s a lifelong science. That’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about being out of shape.’ He made it sound ugly, as well as grave.

‘You mentioned a clue?’ she asked, now quite defensive.

‘Your card has too many names on it.’ He dramatised the counting of the names. ‘One — Edith. Two — the initial A. That counts as a name in this situation. Alison, isn’t it? Three Campbell. Four — Berry. You know what it said to me, what the card said to me?’

‘No, George.’

‘It made me think you were four people trying to crowd together on one card — to come together as one.’

He was breathtaking, She now remembered why he was the most surprising man in the district. He had not gone to university but he was a man who ruminated. He was spirited.

‘That’s fairly psychological, George.’

‘I understand psychology.’

She suspected he meant not the science but psychology as the ‘methodology of life’. Oh God, perhaps he was right about the four names. She’d sensed it when she’d had the new cards printed. It was Florence’s influence; Florence had decided that she would champion Edith to the top and this was part of her plan.

She glanced across at him. Could she admit to this country town go-getter that he was right?

‘We shouldn’t be secretive about our middle names,’ she said, trying to be conversational. ‘I don’t know why we’re all frightened of our middle names. Do we want to keep one name for our secret self?’

George seemed to be remembering. ‘At school we always tried to keep our middle name secret but I ended up being called by my middle name.’ He laughed.

‘It was usually a very old-fashioned name, the name of a grandparent, and we were embarrassed by it,’ she said. ‘Maybe it is our name from our former life — the life before we were born. That might frighten us as children.’

‘That could be right.’

The meandering didn’t get her out of George’s analysis of her card, her life. He had taken up the card again.

‘I’m still finding out how to make my way. That’s the problem, George.’ Her voice sounded almost discouraged. She felt a gust of deep, deep, fatigue, a feeling new to her.

The confession seemed to deflect his investigation. He raised his eyes to the sky, lifted his right hand as if conducting an orchestra. ‘I suppose, though, that truly we are a Federation of Selves. There’s the person within us who goes about the daily affairs and there’s the person who goes in to sleep at night alone.’

She thought to herself that there was also the 3 a.m. person.

She felt tired and tearful.

Ambrose had a persona which was in acute and total disarray but it didn’t matter that much to him. He seemed positively to delight in it.

‘Should we trust the three a.m. person any more than the other selves, George?’ she said. She knew he would know what she meant.

His face seemed to cloud, and he said with defiance, ‘The three a.m. person is the least brave self.’

She thought the 3 a.m. self was the frightened child within. Should it ever have a voice? She saw from George’s reaction that the 3 a.m. self frightened him too.

‘Sometimes it might be the most realistic voice?’

‘No,’ he said, slapping the table, ‘never take counsel of your fears.’ He then left the platitudes and said quietly, ‘I’m wrong. All our inner voices must be listened to, paid their due. The final action of the whole must be decided after listening to all.’ Then with an effort he said, ‘Even the small nasty voices.’

There was silence.

Then in a loud, different tone of voice he said, ‘We have a birthright but we have to honour it and, if required, we have to forgive it in ourselves. I’m thinking of some of the bad things we’ve done as a nation.’

She was glad and relieved that George was a person who could not stay in one chair, or one room, or one place for long, nor on one subject, and that they’d moved away from talking about her. She ran to catch up to his thinking, and said, ‘But, George, isn’t the possibility of regeneration part of our birthright as Australians — the privilege of being able to fashion ourselves?’

George nodded; he liked that idea. He smiled shrewdly. He knew she was mustering herself and beginning to meet his earlier case against her. He conveyed by his smile that he knew his limitations in arguments of this sort. ‘We need you to help make the country, Edith. We need people like you. We’re short of people like you.’

They walked across the garden towards his hotel which was on the other side of the lake. She let herself take his arm.

‘I know, Edy — I know. I too am a man refashioning himself. In that refashioning, we take risks. You take your life, and you work on it with your hands.’ He held out his hands, palms upward. ‘It’s as dangerous as self-surgery.’

George said this as they were opposite Rousseau’s statue. She pointed this out. He insisted on going to view the statue. He looked at it closely, as if examining it for cracks. No one she knew looked at things with quite the scrutiny that George did. ‘Should I read this man’s book?’ he asked her, looking up at Rousseau.

‘I don’t think you need to do that, George. I think you’re a Voltairian. We’ll go to Voltaire’s house if you’ve time tomorrow.’

He was tickled that she tied his name to that of Voltaire. ‘You think so? You see me as a Voltairian? Scribner often mentions the name Voltaire.’

He asked her for a quote from Voltaire but she didn’t know one.

‘I’ll read that man’s books then,’ he said, ‘I’ll need something for the ship. Write down some titles for me.’

That night, as she removed her make-up, sitting at her three-mirrored dressing table, she saw too clearly three selves at least in the cross reflection of the mirrors. She smiled at each, helplessly.

Although George said he wasn’t one for sightseeing, she took him up Salève by cable car. She thought he should do at least that. He paid tribute to the view of Geneva, to Mont Blanc, and the Jura. The view did not stop him talking. ‘I want to raise another of the reasons I’m here in Geneva.’

She wondered when he would get around to talking about his mission. He’d hinted at it, and, in a way, she had not wanted to know about it. She had a foreboding that it might be a proposal of marriage. She knew her answer and had ready an affectionate and careful reply. Obviously, being high above the world on Salève was an appropriately ‘romantic’ locale for a proposal of marriage. She did not want to hurt him. Anyhow, she could never live with a man who didn’t love wine. She braced herself and asked quietly, ‘What’s your mission, George?’

He gripped the railing with both hands, and spoke out to all of Switzerland, to the whole world. ‘To get the United States into the League.’

She broke out grinning and only just controlled her laughter, chastising herself for her vanity, but with relief. ‘George — Woodrow Wilson and many others — ’ again laughter caught her throat ‘— sorry, George, but a great many people have tried to get the Americans into the League. How in God’s name do you think you can?’

He leaned towards her and held his lapel Rotary badge to her. ‘My secret weapon.’

Over dinner at the Beau-Rivage, George tried both snails and frogs’ legs for the first time, pronouncing them more ordinary than he’d expected, and saying he wasn’t sure that he could taste the snails at all because of the garlic. She said that when you did taste them they tasted of the dankest part of the forest floor.

He chewed one in silence.

Then he said, ‘I think I see what you mean.’

She said, ‘You know, George, apart from my family, you’re the only person from Australia who really writes to me still.’

He looked away from her and down at his plate.

‘Why is that?’ she asked.

He looked directly at her. ‘People probably think that you’ve become high and mighty. That you no longer need them. Or that you’re silently criticising them by choosing to live away. You aren’t part of their lives any more, Edy. Edith.’ He looked at her sheepishly. ‘To tell the truth, I was a little scared of meeting you myself. Didn’t know what you might have become.’

She realised that George was frightened of ‘losing her’.

‘I don’t want Australia to lose you, Edith, and I don’t want to lose you.’

‘It won’t lose me, George; I’ll always be Australian. And you won’t lose me either.’

He then took his wallet from his jacket pocket, opened it, and brought out an envelope.

She found herself always worried by his moves. She expected that they would make defeating demands upon her.

He took from the envelope a eucalyptus leaf from Australia and he handed it across to her for her to smell. She did so but found only the slightest whiff of home.

‘It is time for the leaf burning,’ he said.

He put the leaf in the ashtray, took matches from his pocket, and lit it.

She glanced around, feeling slightly embarrassed by the performance.

He pushed the burning leaf over to her. ‘Home,’ he said.

She leaned over and smelled deeply and, yes, it was home. It was the cooking of chops over the open fire, it was Girl Guide campfires, it was the bush on a hot summer’s day, it was the smell of the bush in pain during bushfires. Most of all it reminded her of a balm used by her mother to relieve congestion of the chest when she was little. She was still embarrassed.

‘Thank you, George. You brought that all this way?’

‘I brought it for this purpose.’ He was pleased with himself. ‘About the way you talk …’ he said earnestly, preparing, she could see, to make a pronouncement.

‘I’ll do something about that, George, when I come back. I’ll make myself speak Australian.’

‘That’s not what I was going to say, Edith. I was going to say that I find the way you talk is pretty damned foxy.’

‘Why, thank you, George.’

On the third afternoon, she sat in George’s room at the Angleterre and drank tea while George, in white shorts and white singlet, did his callisthenics with dumbbells and Indian clubs. It had impressed her that he would ask the hotel to get him dumbbells and Indian clubs. She had been impressed, too, that the hotel could find some for him, although there was something of an exercise craze sweeping Switzerland.

When she asked him why he did the exercises he’d replied, ‘For stamina.’

She suggested that exercise should also be a way of developing bodily grace. She herself did not care much for exercise. It seemed an artificial use of the body. A straining of the body in directions it did not wish, naturally, to go. She tried not to look at his male member bouncing around in his shorts.

With his breathing broken by exertion, he said that his life did not have time for grace — just yet — but it did have a need for stamina. Stamina was his objective.

‘You, Edith, you can afford the time here in Europe for grace. Australia is a country in a hurry — and for hurrying you need stamina.

‘After we get things straightened out,’ he puffed, ‘we’ll go in for grace. And believe me, I need the strength,’ he said, ‘to wrestle down my shyness — or it’ll be death of me.’

‘If you don’t take it more slowly, George, those dumbbells will be the death of you.’

Shy? She didn’t think of him that way at all. It was a very personal thing for him to say. She didn’t want to know about George’s weaknesses. She had a picture of him which she wanted to keep and it was not of a shy man. It was of a go-getter. He was the man in a panama hat sitting in the Studebaker, driven dangerously fast by Scribner in dust coat and goggles.

‘I’ve never seen you as shy.’

He stopped exercising. He said to her, dumbbells in his hands, ‘Edith, sometimes I fall exhausted onto the bed when I get home after a day of running about. It’s a dreadful drain on me, going out in public — going about my business. I’m a dreadfully shy person.’

‘I never knew.’ But she had nothing to say either.

She glanced down again at the documents stamped ‘Confidential’ which George had shown her. They came from the League of Nations Non-Partisan Association Incorporated in New York. There was a letter of introduction to Sir Eric written for George by Charles C. Bauer, executive director. Edith knew of this organisation and knew it was sound. George obviously believed he needed more than a handshake to get to see Sir Eric.

‘You know Bauer?’ she asked.

‘Bauer and I got along,’ said George, still short of breath.

She studied the documents to see whether they contained difficulties for her or the League.

‘You can see,’ he said, ‘the plan is to get Rotary International to meet here — organised by the League. Once the businessmen of America see that the League is a well-run outfit we can sell those Americans the whole conception.’

She’d been impressed that George had been guest speaker the night before at the new Rotary Club of Geneva. For a shy man he certainly was a man who made himself known.

She wondered whether bringing businessmen to Geneva and convincing them might work, so that they, in turn, could convince America. She’d told George that she couldn’t arrange for him to meet Sir Eric — she’d told him she didn’t have that sort of influence in the Secretariat. But the truth was she hadn’t wanted the embarrassment of the meeting between Sir Eric and George. Although she had to admit that George was quite presentable and she’d come to see that he was a smart man. But there was the other indeterminate bond between herself and Sir Eric which she wanted to keep untangled and untarnished, which one day might be of professional significance to her. Or even personal significance but she didn’t know what she meant by that.

As George washed his face in the room basin, he said, through the splashing, ‘You don’t seem to be put out by being in a hotel room with a man doing his exercises, Edith?’

‘You’re someone from home, George. And we are old friends.’

Privately, though, she assessed George also as being a real man.

Seated in Sir Eric’s office with George she felt very nervous, but not in the way that she wanted to feel nervous. This was pure dread of what George would come out with.

She knew that Sir Eric and she were going through that morning again in their memories while listening to George.

George had brought about the meeting through the good offices of Bauer and the Rotary Club of Geneva and he had invited her to join them at the meeting. She stared out of the window as George propounded his scheme.

Sir Eric said that the League Council had invited Rotary to send a representative to the Economic Conference and they had. ‘I know that Rotary represents men of the highest standing in their communities. I, and the League, am aware that it stands for some of the same things as the League, and we’re aware also that it’s a growing organisation.’

‘Three thousand, two hundred and thirty-nine clubs with 151,574 members worldwide,’ George said.

‘Quite so,’ said Sir Eric. ‘Impressive numbers.’

‘Sir, it is not the number of men in Rotary which counts but the amount of Rotary in men.’

‘Quite so.’

She supposed George got these sayings from some central bureau of Rotary.

‘Here, then, is my first manoeuvre,’ said George, and pulled from his briefcase a single sheet of paper.

To her discomfort, George then got up and went around to Sir Eric’s side of his desk and, leaning in, began to explain. She hardly listened. She wanted to be out of there.

He said he believed that all sound propositions could be reduced to a single sheet of paper.

She’d joked to him that some people at the League believed every sound proposition could be extended indefinitely to an infinite number of sheets of paper.

After the meeting, outside the Palais Wilson, walking towards his hotel, George turned to her, grinned, and said, ‘See what a shy Australian can do if he dedicates his mind to it?’ and then he added, ‘As long as that shy Australian keeps up his callisthenics.’

On the night before he left they had another grand dinner, and at a point in the meal George said that he had something very serious to say to her.

He was going to propose. She waited while he stacked his finished dishes to one side in a way that had constantly embarrassed her at restaurant meals during his visit.

He put his hand over to cover hers and looking into her eyes, he told her that her mother was not well.

‘Ill?’

‘Very ill, Edith. Your father told me that he believes your mother will not live much longer.’

His hand held on to her and she gripped his. She was thrown off-balance by the news. Letters came regularly from her mother and father and nothing had been mentioned. ‘No one told me!’

George had not mentioned or hinted at it when they had talked about her family.

The money. Her mother had sent the gift of money. She must have been ordering her affairs.

‘I think they felt you shouldn’t be worried. In this new job and living so far away and all.’

She didn’t know what to say.

‘I’m sorry to be the bearer of such news but your father asked me to break it to you. I kept it till the end of my visit because I didn’t want a pall to be cast. That was their idea as well. That was your mother’s wish. That I should mention it only when I was at the end of my visit.’

‘How ill — how soon?’

‘It’s a tumour, Edith. The doctors think she’s dying. Maybe a few more months. She’s been to Macquarie Street doctors. She’s been treated by the best.’

Edith put down her spoon and put both her hands into George’s. He held them tightly.

‘In his letters my father said nothing.’

‘They were being careful about worrying you. You being so far away. There was nothing you could do.’

In her mind she began to plan a return to Australia, although it couldn’t have come at a worse time for her.

‘I guess you’ll be coming home,’ George said.

‘Of course.’

‘Do you want me to see if there is a passage on my ship? You could come back with me.’

‘Thank you, George — no, I’ll have to arrange things here.’

‘I could wait.’

‘You must go about your business, George.’

George left Geneva with his new ideas and his honey spoons on the lake paddle-steamer Italie for Lausanne where he was to join a train for Marseille and home.

Edith’s last view of him was in the Captain’s cabin, having the controls explained to him, and then waving to her. It seemed to her that he captained the boat out.

She smiled away a tear of affection for him and for patrie, for her dying mother.

‘Let me know your ship,’ George had said as he left. ‘I’ll drive up to Sydney and collect you.’

Crying, she waved sadly to him. She blew him a kiss.

That same week, in her office back at the Palais Wilson, Edith happened to see a circular to Under Secretaries-General, Directors and Chiefs of Section. The circular outlined much of what George had told Sir Eric and suggested that members of Secretariat when visiting another country should inform Rotary of their willingness to speak at Rotary meetings, especially in the United States. It said that ‘one of the characteristics of Rotary being the weekly lunch or dinner’.

George had been taken seriously in his own right although perhaps the secret bond between herself and Sir Eric had helped.

She smiled back tears again, this time pleased by the memory of George’s energy, so much of which, she now knew, he used to ‘wrestle down’ his shyness. She didn’t know whether this was a sad knowledge or not. In George there was no aggressive energy. It was an authority which tried to Get Things Done Properly.

Edith grappled with her dilemma about returning to Australia. She could take a home-leave back to Australia. She wrote to her mother and father and said that George had broken the sad news of her mother’s illness to her and she would come home just as soon as she could.

After George’s return to Australia she received an invitation to the wedding of Thelma and George.

She wondered if he’d come to Geneva to ‘look her over’ before deciding. If things had been a little different, she thought that perhaps she might have considered George as a husband. He hadn’t asked and as Florence said, one did, at least, like to be asked.

She observed to herself, pointedly, that during George’s visit she’d kept Ambrose mostly out of sight, except for a few polite drinks, and George, on the other hand, had barely mentioned Thelma. Confused reactions rose in her heart. What was it that he’d found lacking, or was it just that they were headed along different roads? Had she found him lacking and, if so, how? She feared to look, dreading that what it was she saw lacking in him was unworthy of her consideration and that to value those things meant she was becoming condescending or creating a superiority based on spurious values. Was her sense of self causing her to disqualify people? She sent a cable of congratulations and resolved to search for a gift. If, as George had suggested, they’d gone back together, would this have led to a courtship? A shipboard romance?

She was just not ready to go back home yet. Furthermore, she couldn’t afford to leave the League for the twelve weeks travelling there and back together with time away. Too many things were happening.

Her mother wrote a long letter which absolved her from the dilemma and the moral disquiet of her decision not to return home. In her letter her mother said, ‘I would rather think of you going on with your fine work in this one chance that the world has to set things aright than to have you moping at my bedside and fetching lemonade. I would feel proud and happy to know that you were going about your destiny and if you were here, I would fret that you were not in Geneva.’

Her mother said in the letter that she wanted Edith to do great things for which the family would be remembered.

Edith sadly doubted that parents were ever remembered for the greatness of one their children.

She’d known that as Rationalists her father and mother would argue that her life was in Geneva and that her work was more important than, well, customs and rituals of death. They were those sort of people although her mother was far less of a Rationalist than her father.

She wanted to see her mother but she had to take that course which furthered her own life, rather than that which served to comfort the end of her mother’s life.

She hoped that her mother was being truthful when she said that she would be comforted more by her being a good daughter out in the world doing good works.

She cancelled the appointment with Nancy Williams in personnel which she had made to arrange for her leave. She wrote to her mother in these terms and, as she expected, her mother wrote back again affirming her decision and her father did as well.

A few months later her mother died.

She took a week in the Jura on her own but then returned to work. She repeatedly told herself that by staying at work she was affirming life and not doing what the conventions of grief expected and that this would please her mother.

But she was still filled with guilt for not having tried to get home and all her mother’s assurances before she died did not help, and Edith knew she would have to live with her regret for a long time.

Not having seen her mother at her deathbed was unattended-to business and now no way existed for her ever to attend to it and it would remain for ever unattended-to business.