“Nothing’s straight comedy, nothing’s straight drama. In drama there are always elements of comedy. In black culture, you are always trying to laugh through the sadness, and it’s a testament to the experiences that we go through.”1

—ISSA RAE WRITER/CO-CREATOR/EXECUTIVE PRODUCER/ACTRESS INSECURE

Chapter 1

Blurring the Lines

Redefining Genre and Tone in the Dramedy

Is it a comedy or a drama? Or is it a genre-bending dramedy?

I say, as long as it’s good, does it matter?

It depends on whom we ask. For the broadcast and basic cable networks that are still scheduled in rigid timeslots and beholden to advertisers and commercial breaks, categorization still matters a lot.

At NBC, where everything old is new again, scheduling sitcoms in comedy blocks on the same night continues to be a viable programming strategy. Tune in Thursdays and we’ll have a night of laughter, anchored by their reboot of Will & Grace. ABC, CBS and Fox all program their sitcoms in compatible pairs, presuming that if we’ve tuned in to Modern Family or Brooklyn Nine-Nine, we’re probably going to stick around for the complementary shows that follow.

Broadcast networks still need to fill their primetime schedules with series that work in particular timeslots, and they’ll often utilize a proven ratings hit as a launching pad for a new show. Traditionally, the 8:00 to 9:00 p.m. timeslot has been called the “family hour” and offers softer-edged shows that appeal to the whole family, followed by more sophisticated sitcoms and reality TV at 9:00 p.m. and darker, harder-edged crime, legal and/or medical procedurals in the 10:00 p.m. timeslot. But besides sports and live events, who even bothers to watch TV in timeslots anymore? The answer is twofold:

- Generally, viewers over the age of 40.

- Viewers who can’t afford a subscription to a streaming, on-demand service and/or those who simply prefer free TV.

Will & Grace isn’t the only classic sitcom getting a revival, bolstered by the tug of nostalgia; ABC has plans to reboot Roseanne as well. The multi-camera hit series The Big Bang Theory (from the fertile imagination of TV’s successful funnyman, Chuck Lorre) still garners large ratings for CBS (its 2017 season finale scored more than 12.5 million viewers). Nevertheless, its prequel/spinoff, entitled Young Sheldon, is shot single-camera style—without a live studio audience. This delightful dramedy has more in common with nostalgic series The Wonder Years than with its mothership laugh riot sitcom The Big Bang Theory.

Is this a sign of the times that the multi-camera sitcom is on the wane? It’s alive but leaning in that direction, as TV shows have become more cinematic and less static/contained. The big ratings numbers of Big Bang Theory certainly attest to audiences’ enjoyment of three-jokes-per-page traditional sitcoms—especially if the jokes are funny. But having the freedom to follow characters outside of large apartments, office spaces and coffeehouses tends to feel more liberating and surprising. If the characters can go anywhere and not be limited to two “permanent” sets and a “swing” set (an interchangeable set depending on that week’s episode), the episode can feel more organic and authentic—like life.

Like the dramedy that’s between genres, viewers today fall somewhere between traditional and online platforms. NBCUniversal’s niche digital comedy network Seeso announced its closure at barely 19 months old, having struggled to win subscribers. Some Seeso Originals moved to streaming service VRV, while comedies on NBC’s traditional broadcast network continue to flourish. Perhaps Seeso was ahead of its time.

How Did We Get Here?

James L. Brooks is best known for his Emmy Award-winning MTM Enterprises2 sitcoms; the equally lauded sitcom Taxi; and Oscar-bait movies (Terms of Endearment, Broadcast News, As Good As It Gets). He’s also an executive producer of TV’s longest-running primetime comedy series, The Simpsons, but his roots in half-hour dramedy actually go way back to his groundbreaking series Room 222, which aired on ABC from 1969–1974. This single-camera dramedy was time-slotted among traditional sitcoms but features a diverse cast and centers on Pete Dixon (Lloyd Haynes), an African-American social studies teacher at the fictional Los Angeles school Walt Whitman High, and his core group of inquisitive students in Room 222. A far cry from the broad, zany antics of high school “sweat hogs” on Welcome Back Kotter (1975–1979), Room 222 explores contemporary themes with light comedy, nuance and the trials and tribulations of coming-of-age, during the tumult of the late 1960s and early to mid-’70s (including the Vietnam War, feminism, racism, homophobia and even Watergate). Room 222 is my earliest memory of a sitcom that straddles the line between comedy and drama, with an emphasis on authenticity and subtlety, obliquely addressing issues of our times without ever feeling preachy/pedantic.

The half-hour dramedy also has its roots in the TV version of the 1970 Robert Altman film M*A*S*H,3 adapted by Larry Gelbart (Tootsie). The much celebrated, Emmy and Peabody Award-winning TV series aired from 1970 through 1983. Scheduled and packaged by CBS as a sitcom, the series is set in the 4077th mobile army surgical hospital during the Korean War. The early seasons are bloodier and grittier, with laughter interrupted by artillery shells and bombings; the latter seasons feel somewhat slicker, with less gore and more quips. It is inherently a political series that avoids glamorizing war but often makes it look like a whole lot of fun ( just add sex, booze and an unfortunate laugh track). And then Gelbart and his team floor us with a shocking, tragic turn, including the deaths of beloved characters, to remind us of reality (these outlier episodes were sans laugh track). Always a delicate balancing act between comedy and tragedy, the show finds its greatest success by reminding us that despite the worst situations imaginable, laughter truly is the best medicine.

If M*A*S*H and Room 222 are half-hour dramedies masquerading as sitcoms, The Wonder Years (on ABC from 1988–1993) is pure dramedy from the get-go and an anomalous period piece to boot. Like Room 222, The Wonder Years retrospectively explores the tumult of the 1960s/early 1970s through the lens of innocence: the coming-of-age story and, in this case, puppy love. The main focus is the Arnold family’s youngest child, Kevin (Fred Savage), and delves into his school life, home life and blossoming love life. The critically acclaimed hit series’ signature style is in employing voice-over (Daniel Stern, as off-screen narrator/adult Kevin, providing us with insight into young Kevin’s state of mind). Although at ABC’s insistence the show was set in Anytown, USA, the show’s suburban setting and authenticity gave series creator/showrunners Carol Black and Neal Marlens the opportunity to explore controversial political themes—the draft, Vietnam, women’s liberation, race relations—but as background and counterpoint. The Wonder Years is consistently funny but never just goes for the laugh and is devoid of contrived jokes. Instead, it is a character-driven slice of nostalgia and idealism that reminds us of the possibility and wonder that baby-boomers all once felt.

There were other precursors to today’s dramedies: United States (Gelbart’s follow up to M*A*S*H ); Hooperman (created by Steven Bochco and Terry Louise Fisher); Doogie Howser, M.D. (from Bochco and David E. Kelley); The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd (created by Jay Tarses)—most of which would be considered successful in today’s TV ecosystem. Alas, back in their time (and timeslots), they were relatively short-lived but are all definitely worth a second look.

What differentiates a dramedy from a comedy?

Norman Lear pushed the envelope on his classic multi-camera sitcoms in the 1970s (All in the Family, The Jeffersons, Maude, Good Times, One Day at a Time) by balancing laugh-out-loud jokes and funny situations in front of a live studio audience, while also dealing with the controversial issues of race, religion, gender and politics. But Lear went even further with more personal dramatic storylines that encompass divorce, infidelity, cancer, abortion and even rape. These more serious episodes were the exception, not the rule. The broadcast networks have always been more comfortable with funny comedies (with heart) and emotionally resonant dramas with (easily solvable) moral dilemmas.

Most dramedies are not giant ratings champs, but they do have a fiercely loyal, niche fan base. If authenticity is the most desired commodity in the digital TV era, then the dramedy hits that sweet spot by getting real, and rarely sacrificing a raw, emotionally impactful moment for an easy laugh.

Multi-camera sitcoms are, by design, formulaic, familiar and reassuring and must be funny. If the table read in front of the network and studio executives doesn’t generate consistent laughs, the writers will need to stay up all night rewriting the script. A multi-camera sitcom with flat jokes is deadly.

Single-camera sitcoms also need to generate laughs, but through funny, ironic situations and character quirks, more than punch lines. Of course, single-cam sitcoms are also required to be funny.

A sitcom with fewer jokes is … what? That depends. It could be a bad sitcom, or it could be a version of the seminal, genre-bending, tone-blurring dramedy series—either half-hour or one-hour.

Good rules of thumb …

MULTI-CAMERA SITCOM: Half-hour. Funny is money. Mainly interiors, 2–3 main sets; lots of entrances and exits from rooms. Minimum of 3 jokes per page (setups and punch lines); escalate chaos to solve a small problem writ large (a/k/a “tremendous trifles”); restore stasis and love by the end of the episode. A/B/C stories usually have a unifying theme. Little to zero character development. Examples: The Big Bang Theory, Two and a Half Men, Fuller House, One Day at a Time.

SINGLE-CAMERA SITCOM: Half-hour. Mixture of jokes and funny situations. Approximately 60/40 split between interiors and exteriors; humiliate the protagonist(s) and challenge their comfort zones; restore stasis and love by the end of the episode; flashbacks and flash cuts to past moments of embarrassment are employed for comedic effect. Mockumentary and confessionals (a/k/a breaking the fourth wall) are sometimes employed. Usually have a unifying theme. Little, no or slow character development. Modern Family, Silicon Valley, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, The Good Place, The Last Man on Earth, Black-ish, Veep, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Grace & Frankie, Ballers and Fresh Off the Boat as well as Ricky Gervais’ groundbreaking comedy/dramedy series including The Office, Extras and Derek.4

DRAMEDY: Half-hour or one-hour. Honest, raw, uncomfortable relationship issues are explored with nuance and subtext. Generic and familiar plotlines are eschewed entirely. The tone can be funny or tragic but is intentionally off-putting, especially when offering an inconvenient truth. Characters have hyper-specific personality quirks and are more psychologically and emotionally complex. Characters tend to make irrational decisions and are less likable. Avoid formula, with each episode individually crafted to feel distinctive and one-of-a-kind. Can be expansive and cinematic, often featuring multiple locations and fragmented plotlines; usually have an indie movie sensibility and avoid mainstream, obvious/manipulative music choices; the visuals tell the story more than expositional dialogue; usually tell the story in the cut5 to create a tapestry of interwoven storylines; particular music, montages, flashbacks, voice-over, fantasies and magic realism might be utilized. Thematic through-lines may unify each episode, but more likely there’s a season-long theme. Most dramedies are heavily serialized and utilize DPUs6 from episode to episode.

![]()

Dramedies and Life on the Cringe

The pure dramedy may serve up a wholly serious episode, followed by a more broadly comedic one. There’s less of a consistent comedic or dramatic tone, and more of the creator’s sensibility. Authenticity trumps easy laughs. Subtext and nuance are mined for maximum cringe and relatability. If traditional sitcoms are about likably flawed characters getting into and out of trouble, then dramedies are more about coping with the ongoing hardships and moral complexities of relationships.

Sitcoms generally offer well-intentioned characters caught up in their own self-generated chaos; they offer up a problem and a solution—or moral—by the end of the episode.

Dramedies are generally much more ambiguous, and their characters tend to be self-involved, self-destructive, and while forgiveness and love are still the currency required to solve a dilemma, dramedies don’t offer up easy answers.

![]()

Female-Driven Dramedies

HBO’s Sex and the City indeed blazed the trail for women-focused dramedies such as Girls (also HBO) and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (The CW). While SATC is about the search for love, Girls is about self-actualization (or the lack of it), and Crazy Ex-Girlfriend centers around self-delusion. The protagonists are smart, funny women—as well as being relatable, lovable and sexy, they make us laugh. It almost seems unfair to demand so much from female protagonists in dramedies, but it’s a standard we’ve come to expect. Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker), Hannah Horvath (Lena Dunham) and Rebecca Bunch (Rachel Bloom) have deep-rooted vulnerabilities, grow through transformational arcs and always with a good dose of humor, all of which puts them squarely in the hybrid dramedy category.

What also connects these female-driven dramedies, not only to each other but to their audiences, is their authenticity, with their writers drawing on personal experience to create endearing characters who feel real. Sex and the City was originally based on Candace Bushnell’s book about her own 30-something experiences of dating in New York in the ’90s; Girls creator/writer/director/actress Dunham freely admits the show is essentially about herself and her friends; Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is partly based on co-creator/writer/actress Rachel Bloom’s personal struggle with mental well-being. Authenticity is also the female-driven dramedy’s common ground with quality female-driven, half-hour comedies. Creator/writer/actress Issa Rae’s Insecure (HBO) is partly based on her past awkward experiences; the same is true of Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, who created, write and act in Broad City (Comedy Central). And co-creator/writer Whitney Cummings’ multi-cam sitcom 2 Broke Girls (CBS) was informed by the time she spent penniless in her 20s. All six female-driven shows ring true to their time and place; in Insecure/Girls/Broad City/Crazy-Ex/SATC, there is authenticity to the point of rawness: Issa writes from her own experience of being accused of “not being black enough.” In Girls, Lena Dunham confronts stereotypes as a young woman who is highly sexual. Such dramedies and comedies continue to push the kinds of jokes and subject matter that women are broaching on television. Both the female-driven dramedy and comedy recognize the importance of being able to laugh at ourselves even when things go wrong.

Funnily enough, location is also a character in all these shows, which exist in heightened realities: turn-of-the-century Manhattan, the satirical take on hipster Brooklyn/Queens in Girls and Broad City, the fetishized suburbia of West Covina, urban LA and View Park, a/k/a “The Black Beverly Hills” and more. Even the set of the multi-cam 2 Broke Girls is memorable for its brightly colored diner and the girls’ work uniforms. The highs and lows of female friendship are also featured throughout these female-driven shows—from Issa’s bust-up with Molly (Yvonne Orji), to Rebecca’s realizing she’s found a much-needed true friend for life (and maternal figure) in co-worker Paula (Donna Lynne Champlin).

The female-driven dramedy traffics in real human emotions; the characters evolve and reevaluate throughout the series. Although SATC owes some of its DNA to The Mary Tyler Moore Show, the major difference is the dramedy’s willingness to challenge and push female characters to grow. When Mary Richards (Mary Tyler Moore) breaks up with a man she is largely unscathed, appearing in the next episode as if nothing happened. Carrie, on the other hand, wears the scars of every heartache, embarrassment and post-it note inflicted on her during her search for love, as do SATC’s viewers. The emotions that Carrie et al. experience feel genuine, and we recognize them, recalling our past relationships and choices too. The female protagonist’s mistakes and how she learns from them define her and bring us closer together with some laughs to bond us, for good measure.

Express the truth—while finding humor throughout.

![]()

Streaming has ushered in a new crop of half-hour dramedies, available on-demand, across multiple platforms. The half-hour dramedy is polarizing, with some veteran sitcom writers lamenting and deriding them as unfunny, plot-less comedies. It’s a matter of opinion. They’re among my favorite shows on television: fresh, authentic and always surprising. If the high-end cable drama series’ sweet spot is exploring taboos, then the half-hour dramedy is all about the cringe.

Here are some of the best recent half-hour dramedies (and their creators):

- Atlanta (Donald Glover)

- Baskets (Zach Galifianakis, Jonathan Krisel and Louis C.K.)

- Better Things (Pamela Adlon and Louis C.K.)

- Casual (Zander Lehmann)

- Catastrophe (Sharon Horgan and Rob Delaney)

- Chewing Gum (Michaela Coel)

- Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (Aline Brosh McKenna and Rachel Bloom)

- Dear White People (Justin Simien)

- Fleabag (Phoebe Waller-Bridge)

- Girls (Lena Dunham)

- GLOW (Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch)

- I Love Dick (Jill Soloway and Sarah Gubbins)

- Insecure (Issa Rae and Larry Wilmore)

- Love (Judd Apatow, Lesley Arfin and Paul Rust)

- Master of None (Aziz Ansari and Alan Yang)

- Mozart in the Jungle (Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman, Alex Timbers and Paul Weitz)

- Transparent (Jill Soloway)

- You’re the Worst (Stephen Falk)

Following is an analysis of a selection of these shows, while Insecure is featured in Chapter 7.

You’re the Worst: The Anti-Romantic Dramedy

There’s a misconception that “dramedy” means “a show with unlikable characters.” Look at early iterations of modern dramedy such as Weeds, Nurse Jackie, Californication, Rescue Me, Girls, Orange Is the New Black or Transparent: Constant references were made to the “unlikable” characters at the core of these series (it would be naïve not to note that this comes up more often with female characters, whose sole purpose for many years was to be likable). But audiences are realizing that this signifier has a broader definition, welcoming dramedies about flawed nice people (Master of None, Better Things, Insecure) and comedies featuring morally challenged characters who rant, criticize, judge and lash out: Atlanta, Baskets, Fleabag, Casual. I suppose Seinfeld, which featured lovably selfish neurotics, was an outlier sitcom, and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia featured (funny) horrible jerks. And neither was ever considered a dramedy.

The “likability” factor takes an interesting turn in FXX’s You’re the Worst. Just from the title, viewers know they’re in for a show about characters they might like to watch, but wouldn’t want at their house for dinner. What makes You’re the Worst different, however, is how the show takes the trope about horrible people and turns it into a sweet, empathetic and heart-wrenching story about two people desperately trying to learn how to love one another. Unlike its dramedy soulmate Catastrophe, whose leads often make bad and selfish choices but are generally trying their best, You’re the Worst follows three truly terrible characters who constantly hurt those around them. (I’m not including ensemble cast member Edgar, played by Desmin Borges, because he is objectively a delight.) But at the end of the day, Jimmy (Chris Geere), Gretchen (Aya Cash) and Lindsay (Kether Donohue) always harm themselves most of all. You’re the Worst does a masterful job of showing the pain behind the characters’ selfish actions. We get an especially good look at this pain in the Season 2 arc, where Gretchen sinks into a deep depression. It’s a touching portrayal not only of what it’s like to constantly live with a mental illness, but also the reality of loving someone with a mental illness. Creator Stephen Falk gives Jimmy, Gretchen and Lindsay rich backstories and internal lives that make their actions understandable but not redeemable.

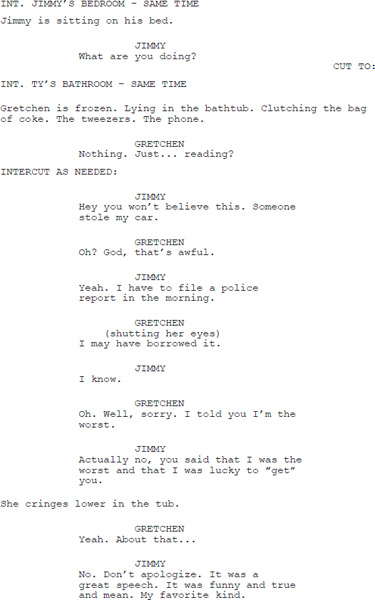

By the end of the pilot, Jimmy has behaved terribly after his one-night stand with Gretchen. Actually they both have, but he was worse. He calls while she happens to be in the bathroom of the LA mansion belonging to douchey director Ty (Stephen Schneider). They’ve just had sex but Gretchen isn’t feeling it tonight. Perhaps because Ty was appalled when Gretchen revealed she burned down her high school to get out of a math test. Clothed in the bathtub, after stashing some of his coke in a take-home baggie, she can’t resist snorting some straight away, using tweezers she’s found. Ty remains in the bedroom, oblivious.

![]()

Baskets and Lives in Disarray

FX’s quiet, dark dramedy Baskets has its main characters constantly begging the question: “What the hell am I doing with my life?” In the beginning of the series, we meet our protagonist, Chip Baskets (Zach Galifianakis) at a crossroads. He’s flunked out of a fancy French clown school in Paris, only to return home to Bakersfield, California, and work as a lowly rodeo clown. In their hometown, twin brother Dale Baskets (also played by Galifianakis) literally sells the possibility of success at the cut-rate Baskets Career College. But it’s Chip and Dale’s mother, Christine Baskets (Louie Anderson), whose journey steals the show. And not by playing a transgendered mom—the series never comments on the fact that a man is playing mom. Baskets just is.

Christine is the epitome of a mother trying to do her best. Left alone by her husband after he jumped from a bridge when the twins were young, Christine has tried to support her sons in all of their endeavors. (This includes Christine’s adopted set of African-American twins, the rarely seen but often bragged about Logan and Cody, played by Jason and Garry Clemmons.) Although the show finds numerous ways for Chip to pursue his true purpose, mess it up and start all over again, it’s often Christine’s hopes and dreams that go unrealized—even though one of her trademarks is her effusiveness for particular, sometimes trivial things: “I LOVE carpeting!” “I LOVE smart animals!” “I LOVE Denver!”

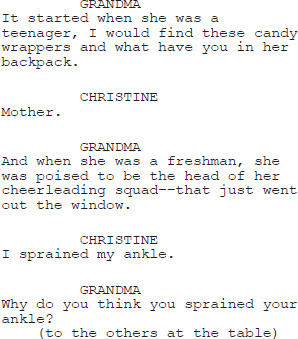

As we see in Season 1, Episode 4, entitled “Easter in Bakersfield,” all Christine wants is a nice Easter brunch with her mother (Ivy Jones), Chip and friend Martha’s (Martha Kelly) family. But when Chip’s selfish obsession with his life gone awry takes over the meal and Grandma criticizes Christine’s weight and begins to tell the whole table about her daughter’s reliance on food as an emotional crutch, Christine’s simple request for a nice Easter meal becomes heartbreaking. Just as Christine’s character is used to inform the audience more about Chip, Christine’s mother is used to show us another, sadder side of Christine. Much of this is brought home thanks to Louie Anderson’s Emmy-winning performance as Christine (which he has described as heavily influenced by his own mother). The performance is unlike anything else on TV, perfectly landing every joke while still playing scenes such as the Easter brunch with the type of vulnerability and shame that comes from being 60 years old and still having to hear that your mother is disappointed in you.

Satire as the Weapon of Reason in Dear White People

D ear White People is based on the 2014 indie film and breakout hit of the same title, which was written and directed by showrunner Justin Simien. As Ann Hornaday writes: “[The movie is] relevant, but, in the right hands, entertaining, too: Simien maintains a scrupulously light tone and deft touch throughout Dear White People.” Both the show and movie are set at Winchester, a fictional, supposedly liberal Ivy League university. “There, African American students—representatives of the ‘talented 10’ percent—grapple with identity, expectations and ambition.”7 The Dear White People series examines polemics by leaning in to the gray areas, layering in sexual chemistry and relationship dynamics. The arc of Season 1 demonstrates that our beliefs—which we can control—may incite change and affirm righteous indignation but can also be overwhelmed by inconvenient emotions, which we can’t.

The half-hour dramedy features a diverse ensemble cast and our protagonist is biracial Samantha White (Logan Browning). On the surface, Sam is a radically politicized activist who hosts the controversial campus radio show, “Dear White People,” in which she holds up a mirror to white culture from a black perspective; in most cases, it’s a funhouse mirror, as Sam admonishes white people to stop dancing or to stop asking people of color the question, “What are you?” as if they’re space aliens. Sam’s demeanor ranges from incredulous to outrage, as she rails at the system—particularly at white male privilege. What keeps the show on track is its smart tone that doesn’t take itself too seriously. This isn’t a preachy series; it’s a referendum on ignorance versus respect. In one of Sam’s many radio rants, she expresses the show’s main theme: Satire is the weapon of reason.

As in the movie, the show makes use of a detached male narrator who observes everything from a humorous, hyper-PC perspective. Simien knows that if we’re going to tackle race issues, first we need to be invited to laugh at our cultural and racial sensitivities. He’s not preaching to the choir here. The POV is fairly balanced, an equal opportunity offender, and the blame and hypocrisy are somewhat colorblind. Today’s politically charged climate is especially intense on university campuses, which can be PC minefields of “micro-aggressions” and “triggers.” When it’s intimated that Sam might be undermining herself by being “a slave to the cause,” it’s simultaneously offensive, provocative and probably true. The series also addresses the Black Lives Matter movement via Winchester’s voluntarily segregated Armstrong Parker (“AP”) House—a haven for the college’s (more or less) marginalized African-American students, the place on campus where Sam feels most at home … or does she?

Sam had intended to teach Winchester’s magazine Pastiche, run by white male students, an embarrassing lesson by capturing on video its “Dear Black People” party, with white students in blackface and masks. But when a caucus of black students learns about the event, they storm the place and pandemonium ensues. Sam escapes the melee, satisfied … until her neglected, secret white boyfriend, Gabe (John Patrick Amedori), reveals on Instagram that he and Sam are a couple. In both the movie and the TV series’ stroke of genius, Sam’s relationship with Gabe effectively leaves her torn between her ideology on race inequality and her passion for Gabe, as she hates what he represents in her worldview, even though she loves him.

It’s one of the many forms of triangulation Simien employs, not only between Sam’s/Gabe’s/her own belief systems, but also between Sam and Reggie Green (Marque Richardson), who is black; Reggie truly likes Sam, and Sam tries to return his affection, but her feelings for Gabe throw her off her game. Sam wishes love could be (color)blind, but it’s complicated. This is but one example of the show’s currency of love/hate relationships that generates significant conflict, drama, pain and humor.

Then there is the overachieving beauty, a black student Colandra “Coco” Conners (Antoinette Robertson), who’s infatuated with Troy Fairbanks (Brandon P. Bell), the president of the Black Student Union who also happens to be the dean’s son. Coco believes she’s in love with Troy, but her judgment is clouded, not by emotion, but by her social-climbing ambition. Troy is wildly attracted to Coco, but he also starts to see the cracks in her persona/façade—which creates another triangle: Coco/Troy/Ambition. Add to that the additional layer of Troy’s black roommate, Lionel (DeRon Horton), who’s a closeted gay man with a secret crush on Troy.

Dear White People plays the race card as satire, but like the best satire, the target is truth—or its various versions that may not be politically correct, or too much so. The show’s tone is funny, ironic, bold and unflinching. Barry Jenkins, who won an Academy Award for Moonlight, directed Episode 5 (written by Chuck Howard and Jack Moore), which explores the use of the N-word and builds to a white cop pulling a gun on a black college kid.

This groundbreaking series coincides with the mainstream use of the word “woke”—a word intended to challenge white people to wake up to the systemic racism and inequality that still permeates and festers in the US and around the world. We need to be mindful of platitudes. Our words matter. I reached out to two trusted friends for their perspectives: Steven, who’s Afro-Latino, Puerto Rican, a writer and identifies as queer, and Tiffany, an African-American female screenwriter (and recovering CNN journalist).

Steven finds the term “woke” problematic. He describes how “woke” was originally a social justice term in the 1960s, resurrected after Michael Brown was shot in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Steven objects to “woke” being appropriated as a catch-all word “that doesn’t take into account socioeconomics or the politics of skin color”; he feels that darker-skinned black people suffer greater discrimination than lighter-skinned blacks. He also believes that institutional racism doesn’t account for the inequality of other marginalized groups, i.e., the LGBTQ community. To Steven, one can claim to be “woke” but still be prejudiced against other marginalized groups. “We parcel out identity, but we don’t acknowledge the intersection,” he explains.

In the show, Sam’s frenemy Coco is darker-skinned and portrayed as uppity—at the expense of her black identity—but flashbacks show just how much Coco has struggled because of her skin tone. In fact, the night after that party, Coco calls Sam out on how she has it easier because of her fairer complexion: “Imagine the reaction if your divisive revolutionary drivel were coming from the mouth of a real sister. You get away with murder because you look more like them than I do.” Meanwhile, Troy is portrayed as athletically gifted, excels academically, is privileged and for a while he appears to transcend race; Lionel is a geek hiding behind the façade of his glasses and Afro, writing about other people to take the focus off himself.

Tiffany is a fan of Dear White People, which she describes as “nuanced in a way that TV—especially dealing with racial issues—rarely is.” To both Steven and Tiffany, the bottom line is that getting “woke” is not a monolith. The show succeeds by shining a light on the intersections between racism, sexism and homophobia, as well as socioeconomic and academic status. It’s an important story about the relationship between identity, respect, resistance and solidarity, all delivered with sharp satire.

I Love Dick: Exploring the “Female Gaze”

If American Gods and Twin Peaks are the most bizarre series on TV today, then I Love Dick (co-created by showrunner Jill Soloway and Sarah Gubbins) takes the prize for the most emotionally raw and daring. Whether its characters are fully clothed or naked, they bare their souls to us and expose their shame in unexpected and provocative new ways. Based on the book by American artist, author and provocateur Chris Kraus,8 I Love Dick is a hybrid of fiction and memoir and explores the writer’s psycho-sexual obsession with a media theorist and sociologist whose name is Dick (played with laconic, low-key, humorous cowboy swagger by Kevin Bacon).

This is extreme cringe dramedy, and a more apt title might be Diary of a Mad Stalker. Soloway has said in interviews that her series explores “the female gaze.” While movies and TV have explored the male gaze (objectifying women) for generations—from Marilyn Monroe’s legs exposed under her billowing white skirt in The Seven Year Itch, to every James Bond and action movie ever made—examples of the female gaze in film and television are historically rarer. There are of course notable exceptions: Written by Oscar-winner Callie Khouri, Thelma and Louise immediately comes to mind. Movies such as Magic Mike and its sequel, touted for featuring male strippers, are essentially designed as bromances, and the men are never exploited. To safeguard your pilot against inadvertent stereotyping and gender inequality, I suggest you put it to the Bechdel test.9 In an industry where women are drastically underrepresented in all roles and objectification is rife, such awareness is more important than ever.10

I Love Dick explores the female gaze in a microcosm, in the small, dusty, hipster town of Marfa, Texas. Our protagonist, Chris (the brilliant, courageous Kathryn Hahn), has just moved here with her professor/author husband Sylvere (Griffin Dunne) for his residency at the local artist colony/institute, helmed by Dick. When Chris sets eyes on Dick, it’s lust at first sight. If her gaze isn’t telling enough, we hear her innermost thoughts via voice-over in the form of highly inappropriate, intimate letters to Dick. Her letters are the central narrative device of the series, and lines from these letters appear in large font on the screen, in bright red. The camera also stalks Dick, and lingers, crotch-level, whenever he’s near.

Chris is falling hopelessly in love with Dick, even though he barely knows she exists, and she’s married. Sylvere knows about the letters, and Chris’ sharing her unbridled lust for Dick at first serves to turn up the heat on their sex life—from non-existent/tepid to passionate. But the truth is, even in the midst of mind-blowing orgiastic sex with her husband, Chris is thinking only of Dick. In one of several touches of magic realism in the series, Dick is present in the room while Chris and Sylvere are making love; Chris’ eyes remain locked with Dick as he looks on. It’s just a delusion in Chris’ mind—which she seems to be losing. By Episode 5, Chris is completely out of control, a slave to her desires. And when Sylvere cries foul and demands that she stay away from Dick and stop writing these letters, Chris’ painful reply to her husband is: “I don’t think I can.” Yes, Chris is ready, willing and able to destroy her whole ordered existence in order to be liberated from rules, limitation, sexism and shame. When it comes to Dick, she’s all in.

Consider some excerpts from her poetic, wildly provocative letters:

And this:

![]()

When her feelings appear to be unrequited by Dick, Chris ramps up her obsession and disregards his pleas to leave him alone. She even prints out her letters and tapes them up all around town for everyone to see. It’s partially to get Dick’s attention (she succeeds and he’s angry and humiliated), but also part of exposing herself. She can’t be discreet and hide any longer. She’s coming out and to hell with what anybody else thinks about it. This is her truth.

The cast is rounded out with an ensemble of other women and men dealing with similar issues of gender identity, shame and marginalization. The character of Dolores/Devon (Roberta Colindrez) is trans with a less-than-supportive mother; Toby (India Menuez) is a young artist obsessed with porn; Lila (Gabrielle Maiden), one of the few African-American women in Marfa, is the curator of Dick’s gallery and yearns to have her taste and vision validated by her white, patriarchal boss. Each woman negotiates identity and liberation on her own terms, with Episode 5 (“A Short History of Weird Girls”), written by Annie Baker and Heidi Schreck and directed by Soloway, the standout of the season; in this anomalous episode, Chris, Devon, Toby and Lily break the fourth wall and directly address the viewer about her/his backstory and first experiences with sexual insecurity and shame.

Once Chris has her sexual awakening, her true self emerges, and there is no going back to her former life of quiet desperation. She’s ready to live out loud, and her lustful letters to Dick evolve into a manifesto and, ultimately, into letters to love itself. I won’t spoil the sensational Season 1 finale, except to say that it involves an inevitable, sexually charged confrontation between Chris and Dick. Now she has his full attention; he’s alert and erect, and the male and female gaze converge in the most shocking and explosive climax I’ve ever seen on a dramedy—bar none. The series is definitely not for the easily offended. It did not get picked up for a second season, although this may be part of Amazon’s bigger shift toward event series (more on this in Chapter 12).

![]()

Master of the Observational: Master of None

Aziz Ansari’s breakout role was that of Tom Haverford on Parks and Recreation. Since Tom the character mostly cares about swagger, networking and being a mogul, it came as a pleasant surprise when Ansari, the actor/writer/ producer, and co-creator Alan Yang developed such a sensitive, grounded and unabashedly charming series. Ansari plays Dev Shah, a working actor who is navigating his life as a 30-something, second-generation Indian man in New York. Now, that premise could lead us to believe Master of None is another in a long line of hang-out comedies about hot young people in an apartment who are somehow always just about to kiss. But instead, this personal auteur comedy treats Dev’s life and relationships with naturalism and fluidity. Friends show up in an episode, disappear and then reappear three episodes later at a brunch to discuss Dev’s texts with a girl, mirroring the real way friends come in and out of our lives. (Unlike many sitcoms, which lead the audience to believe our best friends will always be neighbors or that every night somehow everyone ends up in one apartment.)

Dev’s relationship with his parents adds another touch of authenticity to the show. Ansari bravely cast his own parents in the roles of Dev’s mom and dad Nisha (Fatima Ansari) and Ramesh (Shoukath Ansari). The understanding and empathetic portrait that Aziz and Yang paint of their parents in Season 1, Episode 2 (appropriately titled “Parents”) gives viewers a perspective not only on what it’s like to be the children of immigrants, but to be parents to those children. Master of None’s subtle interpretation of what it’s like to be a child of immigrants adds depth to the trope of a struggling actor trying to make it in New York City. The show consciously addresses the lack of minority representation in the media through Dev’s struggles (ditto for GLOW on Netflix and gender inequality). Master of None has also broken new ground: In 2017, actress/writer Lena Waithe (who plays Denise) became the first black woman to win an Emmy for comedy writing, which she shared with co-writer Ansari. The award was for Waithe’s incredibly personal episode “Thanksgiving,” where Denise comes out to her family. Hers was a profoundly moving acceptance speech:

My LGBQTIA family, I see each and every one of you. The things that make us different, those are our superpowers. Every day you walk out the door and put on your imaginary cape and go out there and conquer the world, because the world would not be as beautiful as it is if we weren’t in it.11

“Parents” digs into the privilege allowed the children of immigrants as a result of their parents’ sacrifice. The episode starts with Dev’s father Ramesh trying to get Dev to help him fix his iPad, but Dev never answers his phone. The scene concludes with Dev brushing off his father, saying he can’t mess with his iPad now; he’s going to see an X-Men movie and doesn’t want to miss the trailers. The exchange is relatable, especially for any child who’s had to help his or her parent set up some form of technology.

What gives the episode an introspective quality is the series of flashbacks that follows: We go back to India, 1958. A young Ramesh (Tarun Vaidhyanathan) plays enthusiastically with an abacus on the street, that is, until a bully comes up and crushes it under his feet. In another flashback, this time to 1980 New York City, we see Ramesh, straight from medical school, arrive in America to go to work as a doctor. When Ramesh inquires about the steak dinner for his family all new doctors are treated to, the racist doctor giving him a tour tells him there will be no dinner; Ramesh and his family can eat in the cafeteria. The last flashback is to Ramesh gifting a young Dev a desktop computer—a major leap from the abacus Ramesh cherished as a child. We see a similar scene play out between Dev’s Taiwanese-American friend—Brian Cheng (Kelvin Yu) and his father. We observe the struggle Brian’s father went through to provide a better life for his family and, again, Brian’s blindness to that struggle.

Here, creators Ansari and Yang (after whom Brian is modeled) evaluate their own relationship with their parents and acknowledge the struggles they have gone through for their children. Brian and Dev both seek verbal affirmations from their parents that they’re proud of them, but in the mind of Ramesh and other immigrant parents, they show their love for their children by creating a better life with better opportunities than they had.

Here, Dev and Brian discuss the difference between Asian parents and white parents as they walk down the street after a movie. Dev’s cell phone honks.

In the first episodes of Season 2, Dev travels to Modena, Italy, to learn how to make pasta. Ansari has said that he learned not only how to cook, but also how to speak conversational Italian. We get the sense that making his show is part of his personal journey, and Ansari and his character Dev both come across as wandering, restless souls who second-guess and overthink everything. But Dev isn’t a complaining neurotic; he is much more optimistic. At his core, he is a hopeful, not hopeless, romantic. The show is called Master of None, but it might more accurately be called Lust for Life—even when life is crushing. No pain, no gain. It is, after all, a dramedy.

Better Things: Philosophical Vignettes

In Better Things, co-creator/showrunner/star Pamela Adlon draws our attention to the internal life of a divorced, single mother trying to raise three daughters by herself. The series is semi-autobiographical, which adds a layer of meta-authenticity: Is this art imitating life, or vice versa? What does it matter, when it’s so poignant, relatable, cringe-worthy, sometimes sad and usually very funny? The series has a bemused, sometimes acerbic, comedic sensibility. The opening theme song, “Mother” by John Lennon, perfectly sets the tone for this melancholic slice of life, as it plays over images of Sam and her girls.

What pulls Better Things into the dramedy category is that, throughout the episodes, we see Sam navigating her doubts and insecurities while juggling a freelance career as a middle-aged Hollywood actress, trying to find Mr. Right, or at least Mr. Right Now; her complicated teenaged/pre-teen daughters and their issues; and her own eccentric, boozy mother (who lives right next door). And don’t you dare call Sam or Adlon “brave” for being so plucky and vulnerable—or she might punch you in the face for being patronizing. Moreover, she’s tough. We root for Sam because she’s unapologetically genuine and suffers fools by confronting them—not to attack or shame them, but to understand them. To say her piece. Amidst all the noise in her life, Sam doesn’t demand validation or accept bullshit. She just needs to be acknowledged and heard. Yet, she’s hardly a control freak. All she ever really wants is to tame the chaos, not conquer it—she’s too exhausted for that. And so, for now, she copes and hopes for better things—which for her means happy kids, steady work—and getting laid. In Adlon’s show, we might finally have a true comedic portrayal of what it means to try and “have it all.”

The realism Pamela Adlon achieves by basing the series directly off of her life is crucial for the emotional beats to land. It makes the show approachable, relatable and equalizing in experience.

Love and Death in Atlanta

When it comes to authenticity, it’s tough to surpass the wry, ironic, gritty, satirical world that is Atlanta. Tonally, the show defies categorization but can be best described as an existential comedy, or more accurately a tragicomedy; it’s an example of how cognitive dissonance can be rewarding to viewers. It’s not whiplash storytelling for the sake of being provocative; series creator/showrunner/director/star Donald Glover is just keeping it real. But the problem for his alter ego, protagonist Ernest “Earn” Marks, is that life is too real. He may have dropped out of Princeton for undisclosed reasons, but he’s now enrolled in the School of Hard Knocks. In 2017, Glover became the first black person to win an Emmy for directing for a comedy series, and the first black actor to win lead actor in a comedy series since 1985. “It’s pretty obvious people in dystopian societies don’t realize they’re in dystopian societies,” he said after the ceremony. “I just want people to be aware, I think people are aware.”12

From the opening (teaser) of the funny pilot episode forward, Glover makes it clear to his audience that they’re in for a destabilizing ride—so don’t get too comfortable. Akin to today’s best dystopian and supernatural series, on Atlanta, anything can happen. Glover can write funny and score laughs at throwaway one-liners, but much of the show’s comic relief comes from Earn’s perpetually stoned, eccentric friend, Darius (Lakeith Stanfield)—a walking non sequitur. In the pilot, out of the blue, Darius asks Earn’s father if he can measure a tree in his front yard. Earn’s mom and dad have perfected the art of the deadpan and manage to steal every scene they’re in. There’s also a middle-aged woman at the airport shilling Delta Airlines credit cards (the rival of Earn and his friend) who taunts Earn by flirtatiously snagging a male customer and then gyrating doggie-style behind the oblivious customer’s back.

But these laugh-out-loud moments are juxtaposed against scenes of police brutality, of negotiating the use of the N-word and of cold-blooded murder. How can a dramedy be so gritty and tragic? In today’s television landscape, authenticity trumps laughs—even in a half-hour format. Donald Glover shows us the Atlanta he knows, loves and hates. (The city, in all its contradictions, is a character in the series, the way Baltimore is a character in The Wire.) One moment Earn and his buddies are laughing it up; the next moment they could be dodging bullets or accused of a crime—in a rush to judgment based on stereotyping—they may or may not have committed.

In the pilot episode, “The Big Bang,” an altercation with a pimp/thug leads to a gunshot and probable death. In Episode 2, “Streets on Lock,” Earn’s rapper cousin Alfred (known as Paper Boi and played by Brian Tyree Henry, Earn’s only client as a nascent music manager) and Alfred’s sidekick Darius are released on bail for the previous night’s melee, but Earn remains in custody. Stuck in jail and hoping that his ex-girlfriend (and mother of his child) Van (Zazie Beetz) will, once again, come to his rescue, Earn witnesses the cruelty of our flawed justice system, as a mentally ill man dances around the waiting area in a hospital gown, then drinks from a toilet and spits the water into the face of a police officer. Earn is horrified by the cop’s immediate, violent beating of the homeless man. Clearly the man needed psychiatric treatment, not brutality.

To counterbalance this harsh moment, Glover layers in a macho guy who discovers that his pretty girlfriend is trans—and plays the guy’s cluelessness and trans/homophobia for laughs. Everyone in the jail laughs at him, too—except for Earn, who tries to help:

![]()

The confused, outraged man responds with, “I know what you think she is, but I ain’t on that faggot shit.” One point for intolerance, zero for Earn. This disconnect is meant to break the tension with humor and, like Paper Boi’s earlier refrain of “I hate this place,” it’s clear that Earn hates this place even more; it represents how oppressed and subjugated Earn feels in his everyday life.

The show’s episodes seamlessly and organically swing from comedy to tragedy and back again, but the Season 1 finale, entitled “The Jacket,” is the most controversial and inevitable. The episode centers around Earn’s lost bomber jacket that he believes he left behind in an Uber after a wild night of partying. We know the jacket has great value to him, and he’s on a quest to get it back. But we don’t find out until near the end of the episode that it’s not the jacket he needs so badly, but actually a key to a storage locker (more on that in a moment).

Meanwhile, Earn tracks down the Uber driver, Fidel Arroyo (Tobias Jelinek) via phone and convinces Paper Boi to give him a ride out to the Atlanta suburbs (with Darius riding along as always). They arrive at Arroyo’s address and stake out the house. As they wait, Earn gets a call from popular rapper Senator K (Qaasim Middleton) who invites Paper Boi to go on tour with him. This is their big break! But Earn is skeptical and guarded from a life of disappointments, and Paper Boi is getting antsy: Three black men have been parked in the same spot for too long, and they look suspicious.

As Paper Boi starts to drive away, they’re cut off by police vehicles and surrounded by a dozen cops in SWAT gear brandishing assault rifles. It turns out that Fidel Arroyo is a suspected drug and weapons trafficker. As Earn, his cousin and Darius put their hands on the cop car in compliance, Fidel tries to make a hasty escape—and is gunned down by an overzealous white cop. Here we go again: the shooting of an unarmed Hispanic man in the back, the spurting of blood, and the dead body lying on the ground. It’s a shocking moment in any context, but this is a dramedy. It’s beyond provocative. It’s horrifying. I counted ten shots.

Understandably, Earn, Paper Boi and Darius are rattled—and relieved at being spared. For the first time since the pilot in which Earn managed to get Paper Boi some airplay on a local radio station, Earn feels lucky to be alive. By now, Earn’s sometimes girlfriend and baby momma Van has newfound respect for Earn’s principles (bolstered by their bizarre experience in Episode 9, “Juneteenth”), and she invites him to spend the night at her place. But Earn declines. He knows he must stand on his own two feet. He could have easily been killed today, so now he’s more determined than ever to be independent and live on his own terms—even if home, for the time being, is a storage locker. Ironically, the key was not in Earn’s jacket pocket after all; he’d given it to Darius for safekeeping.

Without the bitter, there’s no context for the sweet. Without struggle, the reward feels empty or tinged with fear that it’s unsustainable. These shows demonstrate the interstices in our lives. The ellipsis between a dissatisfied “here” and some abstract or idealized notion of “there.” We tend to watch TV during our own interstices, and for varied reasons—to pass the time, for distraction, for inspiration—and yes, escape. Seeing fictional characters who are as uniquely flawed as we are also treading water is comforting. We identify with characters who are always yearning and waiting for the next big thing. But every moment matters, and even the insignificant ones are significant in a great half-hour dramedy. It’s the accumulation of the smallest details and the struggle between the repression and expression of emotions that pulls us in and keeps us invested in the outcome. In several respects, the dramedy has flourished because it’s like life.

Bonus Content

Bonus Content

Further analysis on dramedies, including the rise of the genre and the shows Catastrophe and Casual is available at www.routledge.com/cw/landau.

See also: Chewing Gum on Netflix and Fleabag on Amazon (a co-production with BBC Four). In Fleabag, a pitch-black dramedy, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and grief have never been funnier or more disturbing. River on Netflix is a one-hour, drama/crime-procedural that shares some of Fleabag’s touching irreverence. And One Mississippi is a dark dramedy starring one of the drollest comedians on Earth, Tig Notaro. The Amazon show is co-created and executive produced by Oscar-winning screenwriter Diablo Cody (Juno).

Notes

Episodes Cited

“Pilot,” You’re the Worst, written by Stephen Falk; Hooptie Entertainment/FX Networks/Bluebush Productions/FXX.

“Easter in Bakersfield,” Baskets, written by Samuel D. Hunter; Pig Newton/Slam Book/3 Arts Entertainment/FX.

“A Short History of Weird Girls,” I Love Dick, written by Annie Baker and Heidi Schreck; Amazon Studios/Topple Productions.

“Parents,” Master of None, written by Aziz Ansari and Alan Yang; Universal Television/Netflix.

“Streets on Lock,” Atlanta, written by Stephen Glover; RBA/343 Incorporated/MGMT Entertainment/FXP.